You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

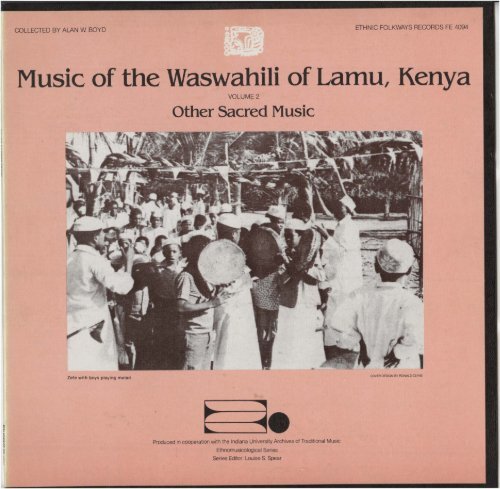

COLLECTED BY ALAN W BOYDETHNIC FOLKWAYS RECORDS FE 4094<strong>Music</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Waswahili</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lamu</strong>, <strong>Kenya</strong>VOLUME 2o<strong>the</strong>r Sacred <strong>Music</strong>Zefe with boys playing matariCOVER DESIGN BY RONALD CLYNEProduced in cooperation with <strong>the</strong> Indiana University Archives <strong>of</strong> Traditional <strong>Music</strong>Ethnomusicological SeriesSeries Editor: Louise S. Spear

ETHNIC FOLKWAYS RECORDS FE4094<strong>Music</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Waswahili</strong><strong>of</strong> Larnu, <strong>Kenya</strong> VOL. 2O<strong>the</strong>r Sacred <strong>Music</strong>COLLECTED BY ALAN W. BOYDOTHER SACRED MUSICSIDE 1Band 1 SamaiBand 2 KasidaSIDE 2Band 1 DhikiriBand 2 ZefeBand 3 Funeral ProcessionTHE KENYA COAST \\SOMALIA\\\oKEN YASource J Oe v Allen. lomu, <strong>Kenya</strong> cuec 1983 MAM®© 1985 FOLKWAYS RECORDS & SERVICE CORP.632 BROADWAY, N.Y.C., 10012 N.Y., U.S.A.<strong>Music</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Waswahili</strong><strong>of</strong> Larnu, <strong>Kenya</strong> VOL. 2O<strong>the</strong>r Sacred <strong>Music</strong>DESCRIPTIVE NOTES ARE INSIDE POCKETETHNIC FOLKWAYS RECORDS FE 4094

ETHNIC FOLKWAYS RECORDS Album Nos. FE 4093, FE4094, FE4095© 1985 by Folkways Records & Service Corp., 632 Broadway, NYC, USA 10012<strong>Music</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Waswahili</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Lamu</strong>, <strong>Kenya</strong>coUected by Alan W. BoydVolume IMaulidiVolume IIO<strong>the</strong>r Sacred <strong>Music</strong>Volume IIISecular <strong>Music</strong>Produced in cooperation with <strong>the</strong> Indjana University Archives <strong>of</strong> Traditional <strong>Music</strong>Ethnomusicological SeriesSeries Editor: Louise S. Spear

<strong>Music</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Waswahili</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lamu</strong>, <strong>Kenya</strong>Collected and annotated by Alan W. BoydSwahili is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most widely known ethnicnames <strong>of</strong> Africa. It is associated with <strong>Kenya</strong> and Jomo<strong>Kenya</strong>tta, Tanzania and Julius Nyerere and such wordsas simba, safari and ijumaa. Yet very little is commonlyknown about who <strong>the</strong> <strong>Waswahili</strong> (<strong>the</strong> Swahili people)are, where <strong>the</strong>y are located or what <strong>the</strong>ir culture is like.Swahili is thought to be an Africanized version <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Arabic term for coast, sahel The Waswahi/i are coastalpeople living in cities, towns and villages on <strong>the</strong> eaSternlittoral <strong>of</strong> Africa from Kilwa at <strong>the</strong> mouth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RufijiRiver in <strong>the</strong> south to Mogadischu in Somalia in <strong>the</strong>north. The common characteristics <strong>of</strong> people whocan be called <strong>Waswahili</strong> are a more-or-less-knowndescent from Arabic families, especially from <strong>the</strong>sou<strong>the</strong>rnmost portions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arabian peninsula; <strong>the</strong>Muslim religiOUS faith; speaking a mutually understandabledialect <strong>of</strong> Kiswahili; and association with, ifnot actual occupation <strong>of</strong>, urban centers.Swahili culture and language are thought to haveoriginated long before <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ProphetMuhammad with <strong>the</strong> contact between Arab traders,sailors and merchants, and Bantu groups along <strong>the</strong> FastAfrican coast. This process reached a high point during<strong>the</strong> internal struggles for preeminence in <strong>the</strong> enlargingMuslim world during <strong>the</strong> centuries following hisdeath. By <strong>the</strong> thirteenth century, Arabic settlementswere widespread along <strong>the</strong> whole <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Fast Africancoastline. From that time on, settlers arrived on <strong>the</strong>Fast African coast in successive waves. Descendants<strong>of</strong> earlier immigrants became more and moreAfricanized, so that today, although Arab influenceis readily perceived in much <strong>of</strong> Swahili culture, andmany people still maintain considerable contact with<strong>the</strong> Saudi Arabian peninsula, <strong>the</strong> culture is clearlyAfrican.The three volumes in this <strong>Waswahili</strong> series contain amusical portrait <strong>of</strong> Swahili culture as it exists in lamu.<strong>Kenya</strong>, and its environs. They clearly illustrate <strong>the</strong>deeply rooted Arabic influence, and yet <strong>the</strong>y alsodemonstrate <strong>the</strong> African foundations <strong>of</strong> Swahili culture.<strong>Lamu</strong> was chosen as <strong>the</strong> focus for this collectionand <strong>the</strong> research it represents because it has been acenter <strong>of</strong> Swahili culture for many centuries and isstill a relatively unadulterated location for Swahili life.This is not to say that all Kiswahili-speaking peopleare like <strong>the</strong> people <strong>of</strong> lamu, or that this collectionexhausts <strong>the</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> musical expression that can befound in Swahili towns, but it does represent Swahilimusical life well and provides examples <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> forms in common use. The notes for each bandprovide more detail on <strong>the</strong> styles <strong>of</strong> music as well asfur<strong>the</strong>r elaboration on <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lamu</strong>, Swahilisociety and <strong>the</strong> culture relevant to it.<strong>Music</strong> oj <strong>the</strong> Waswahilt oj <strong>Lamu</strong>, <strong>Kenya</strong>Volume IVolume IIVolume IIIMaulidiO<strong>the</strong>r Sacred <strong>Music</strong>Secular <strong>Music</strong><strong>Lamu</strong><strong>Lamu</strong>, <strong>Kenya</strong>, is at <strong>the</strong> same time, a district in <strong>the</strong>governmental segmentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, an archipelago<strong>of</strong> islands <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>ast coast <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>islands in that group, and <strong>the</strong> major town on thatisland (see Map I). <strong>Lamu</strong> Island, which is about tensquare miles in area, lies one hundred kilometers southlatitude. Directly to <strong>the</strong> north <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lamu</strong> is Manda Island,which is approximately <strong>the</strong> same size as <strong>the</strong> island <strong>of</strong><strong>Lamu</strong>, and north <strong>of</strong> Manda is Pate, <strong>the</strong> largest island <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> group, on which are found <strong>the</strong> towns <strong>of</strong> Pate, Faza (orRasinj) and Siyu, as well as a few o<strong>the</strong>r smaller villages.Although <strong>the</strong> exact dates <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first settlements on<strong>Lamu</strong> Island are not known, preliminary archeologicalexplorations suggest that settlements occurred in <strong>the</strong>vicinity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present town at least as early as 1200 AD.lamu Island is a sand bar in <strong>the</strong> shape <strong>of</strong> a bow!. Thecenter holds fresh water, while <strong>the</strong> rim prevents <strong>the</strong>brackish sea water from penetrating <strong>the</strong> disc. Sincewells can be dug near <strong>the</strong> edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> island, townscame to be established on its coast. The present daycity <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lamu</strong> lies on <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>astern edge <strong>of</strong> this bowlin a protected bay. The town <strong>of</strong> Matandoni lies on <strong>the</strong>2

The lamu waterfront, a zeJe procession underwayopposite coast <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> island and rests near <strong>the</strong> mouth<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lamu bay.lamu has never been an isolated community. Althoughit is not easily reached by land even today, it has alwaysbeen accessible by sea, ei<strong>the</strong>r from <strong>the</strong> north or <strong>the</strong>south, depending on which way <strong>the</strong> monsoon winds areblowing. The town has a rich history <strong>of</strong> conflict andalliance with neighboring towns, especially Pate.The Pate Chronicle, an indigenous description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>traditions and events in <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> Pate, which wasreduced to writing at <strong>the</strong> turn <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> twentieth century,is full <strong>of</strong> references to political, economic and religiousdisputes with <strong>the</strong> inhabitants <strong>of</strong> lamu (Werner:1915).lamu's history, <strong>the</strong>n, indicates a pattern in which <strong>the</strong>town sought both religious and commercial independencefrom its neighbors, but was never able t<strong>of</strong>ully achieve ei<strong>the</strong>r. Today it is still a mixture <strong>of</strong> a desirefor independence and friendly relations with o<strong>the</strong>rpolitical bodies, so long as <strong>the</strong> interaction resultsin advantage to <strong>the</strong> leading families <strong>of</strong> lamu.Most residents <strong>of</strong> lamu today describe <strong>the</strong> townas divided into two halves-Mkomani to <strong>the</strong> north andLangoni to <strong>the</strong> south (see Map II). The nor<strong>the</strong>rn portionis characterized as <strong>the</strong> place <strong>of</strong> stone houses, whereold established families reside, while <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn issaid to be <strong>the</strong> place where wageni, i.e., visitors, livein mud-walled, thatched-ro<strong>of</strong> houses.Persons from old, established families are proneto emphaSize <strong>the</strong> names <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two locations, to pointout wageni on <strong>the</strong> streets and to call attention towhere people live, whereas more recent settlers in<strong>the</strong> community pay less attention to <strong>the</strong> division.When <strong>the</strong>y speak <strong>of</strong> it at all, it is with a resentful tone<strong>of</strong> voice and a suggestion <strong>of</strong> defiance <strong>of</strong> an obsoletedistinction.Today, although <strong>the</strong> names <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> divisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>to\',ll1 are widely used and <strong>the</strong> social distinctions <strong>the</strong>yimply are !mown to nearly everyone living in lamu, <strong>the</strong>political structure that was once contained within <strong>the</strong>mhas been elaborated and modified. The existence <strong>of</strong>a modern, independent <strong>Kenya</strong> has brought a newdimension to lamu's political structure, which hasbeen partially assimilated into <strong>the</strong> old didemic arrangement,and which has partially changed to meet <strong>the</strong> neworder. A town council still exists, but instead <strong>of</strong> itsmembership consisting <strong>of</strong> leaders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dominantfamilies, <strong>the</strong> wangwana, <strong>the</strong> positions are held byelected representatives, some <strong>of</strong> whom represent <strong>the</strong>interest <strong>of</strong> recent immigrants to <strong>the</strong> town or <strong>of</strong> recentlyenfranchised servant classes. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> prestigiouswazee, <strong>the</strong> leaders <strong>of</strong> important families, still exerciseinfluence upon <strong>the</strong> decision-making processes, but<strong>the</strong>y do so through behind-<strong>the</strong>-scenes pressure uponrelatives or allies from o<strong>the</strong>r families.The political organization <strong>of</strong> lamu is closely intertwinedwith <strong>the</strong> religiOUS organization, which exercisesgreat influence on every aspect <strong>of</strong> lamu society. "Islamhas an order <strong>of</strong> clergy but no priesthood" (Trimingham1962:37). The role <strong>of</strong> leadership in each local mosque3

African influence.Drums are played in ensembles with a double reedaerophone called zumari, which is played with acircular breathing technique. In vugo, <strong>the</strong> zumari hasbeen replaced by a modem trumpet, called tarumbeta.Ano<strong>the</strong>r instrument in <strong>the</strong> ensemble is <strong>the</strong> utasa, aflat metal dish placed inside a larger metal cookingtray, sania, which is struck with two pieces <strong>of</strong> thickrope called zibojolo. Used in almost every ensemble,<strong>the</strong> utasa adds a higher pitched, almost piercing,rhythmic sound to <strong>the</strong> lower throb <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> drums.Three o<strong>the</strong>r instruments are limited to religiouscontexts. The first <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se is <strong>the</strong> tari (pI. matari), aframe drum which is held in <strong>the</strong> left hand and struckby <strong>the</strong> fingers or palm <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right hand. The tariresembles a large tambourine because <strong>of</strong> its Singlehead, <strong>the</strong> metal discs placed in holes in its frame and<strong>the</strong> manner in which it is held. Because it is struckwith intricate finger and hand patterns in ensemblewith o<strong>the</strong>r matari and without <strong>the</strong> shaking that is socharacteristic <strong>of</strong> tambourines, and because its sound isdeep and resonant ra<strong>the</strong>r than sharp and ringing, it isbest classified as a drum. The Arabic name for <strong>the</strong> tariis daf, although <strong>the</strong> daf does not usually include <strong>the</strong>metal discs in <strong>the</strong> rim <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> drum that are part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tari.The second instrument is <strong>the</strong> kigoma (pI. vigoma), asmall Single-headed drum which is struck hard by <strong>the</strong>fingers <strong>of</strong> one hand, adding a snapping sound to <strong>the</strong>matari ensemble. The third is <strong>the</strong> nai, a small endblownflute with five finger holes on <strong>the</strong> upper surfaceand a thumb hole underneath. Today nai are made <strong>of</strong>metal or plastiC, but formerly <strong>the</strong>y were crafted frombronze or wood.The instruments played to accompany secularevents are never played in mosques. In addition, <strong>the</strong>nai, <strong>the</strong> tari and <strong>the</strong> kigoma have been accepted into<strong>the</strong> mosques <strong>of</strong> lamu only since <strong>the</strong> early years <strong>of</strong> thiscentury, and a minority <strong>of</strong> men still oppose such usage.They say a mosque should be a quiet place, a place <strong>of</strong>prayer; instruments create noise. The large majority <strong>of</strong>lamuans disagree with <strong>the</strong>m and so <strong>the</strong> dispute todayis limited to only one mosque in which no instrumentsare permitted. Most people would agree with aleading teacher in lamu who says that it is better thatboys make mUSic, sing and dance in <strong>the</strong> mosques topraise Allah than to be forced to sing in <strong>the</strong> streetsfor secular reasons.ReferencesTrimingham, J. Spencer1%2 Islam in East Africa. London: Edinburgh HousePress.Werner,A1915 A Swahili History <strong>of</strong> Pate. Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RoyalAfrican Society, 14: 148-161,278-297, 392-413.AcknowledgmentsThese recordings were made while conductingfield research in lamu, <strong>Kenya</strong>, in 1976-1977. Theresearch was made possible by a National ScienceFoundation Grant for Improving Dissertation Researchin <strong>the</strong> Social Sciences, a National Defense Fellowshipfrom Indiana University, and a personal loan frommy bro<strong>the</strong>r, Dr. Howard W. Boyd.The Archives <strong>of</strong> Traditional <strong>Music</strong> at IndianaUniversity generously provided <strong>the</strong> blank tapes for<strong>the</strong>se field recordings and <strong>the</strong> facilities for preparing<strong>the</strong> master copies for <strong>the</strong> discs. I am particularly gratefulto Louise Spear, Associate Director, Anthony Seeger,Director, and Frank Gillis, Librarian Emeritus andformer Director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Archives <strong>of</strong> Traditional <strong>Music</strong>,for <strong>the</strong>ir support throughout this project. My thanksalso to Amy NOvick, Archives librarian, for her editingand creativity during <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se discs.The photographs used in this booklet were takenby Susanne N. Boyd. The publication <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se recordingswas supported by a Baker Fund Award from OhioUniversity.The original recordings on <strong>the</strong>se discs were madeon a, Nagra IS-DT recorder at 3314 ips using SennheiserMD21 and AKG CK8 microphones.Alan W. BoydMaster tapes: Nancy A Cassell and Alan W. BoydPhotographs: Susanne N. BoydGraphic design: Amy E. Novick5

THE KENYA COAST\\SOMALIA\\\KENyAWitu•FORMOSABAY•MalindiNORTHINDIANOCEANLAMUISLANDo5 miles!!! ~iiiiiiiiiijjo4080 milesSource: J. De V. Allen, <strong>Lamu</strong>, <strong>Kenya</strong>O.U.C.C. 1983 M.A.M.Map!6

~LAMU HARBOR and TOWNTo MotandoniMOSQUES/ ( I. Mwono Mshomui v1 2. Jumoo/0 CJ (: f:::::::J 3. N'Loloi 0 4. Rodho4:J~IJk1L .i"l?.J (j CJ CJ 0 :.. :~Qf:Qo~ I /;;7 l//~ 51 Q -.-.- Mk,"",";,"'L ••• ~;We! I~ !7,-, '!i/, ~W '",'on." ••---J" ,~lJ!Lif">~~ fly f>~~ ¢;l~o~ c;:J! "W7~ r:::l U~Rry/ti::!;14r5)~[1LJ{dQ~~~~LJ 0::Ii" II wi;;9QnOi~~UV.t,::v;3~PJ~ °o~no~G~~--"UU[!J ----_-CustomsJellyJ....

The first volume in this collection contains examples<strong>of</strong> five forms <strong>of</strong> maulidi: Maulidi ya Kiswahil~ Maulidiat-Habshi, Maulidi Barazanji, Maulidi Diriji andMaulidi Sharaful Anam or Kukangaya.Maulidi is <strong>the</strong> most popular musical form in I.amu.It is first <strong>of</strong> all a Muslim ritual marking <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Prophet Muhammad, but it is also, both to <strong>the</strong>local participant and to <strong>the</strong> outside observer, anexciting performance. It reaches a peak <strong>of</strong> public display'during <strong>the</strong> month-long annual celebration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> actualbirth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet, but it also occurs throughout <strong>the</strong>year in private celebrations in homes or public recitalsin <strong>the</strong> mosques or on <strong>the</strong> streets <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town. The fivedifferent styles in use in I.amu all consist <strong>of</strong> chantedreadings and hymns in praise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet. In spite <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> strong musical component in maulidi, people referto it as "readings" ra<strong>the</strong>r than music, <strong>the</strong>reby reflecting<strong>the</strong> orthodox Muslim reluctance to be involved in <strong>the</strong>overindulgence or uncontrolled expression <strong>of</strong>tenVolume IMaulidlSide 1Maulidt ya KtswahUtassociated with musical performance.The forms <strong>of</strong> maulidi contain texts describing eventsin <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet and maxims for proper livingderived from <strong>the</strong> Prophet's example. These are chantedby a religiOUS leader in a style similar to <strong>the</strong> chanting<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sacred Koran. Interspersed with <strong>the</strong>se readingsare <strong>the</strong> hymns in praise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet, usually sung byall in attendance. In three <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> styles, <strong>the</strong> matariaccompany <strong>the</strong> hymns, while in two, <strong>the</strong> hymns aresung without instrumental accompaniment, usingbody rhythm to establish <strong>the</strong> basic pulse.The examples on this record demonstrate clearly<strong>the</strong> commonality <strong>of</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> five styles. Thedifferences among <strong>the</strong>m should also be apparent.Different groups and individuals in I.amu have <strong>the</strong>irfavorite styles, which are used at various times andon different occasions, but nearly everyone in I.amuwould heartily agree that maulidi is undoubtedly <strong>the</strong>irmost treasured musical form.Maulidi ya Kiswahil; as it exists today, has developedout <strong>of</strong> older forms which can no longer be clearlydescribed by <strong>the</strong> people <strong>of</strong> I.amu. The readings used inMau/idi ya Kiswahili are <strong>of</strong>ten referred to as Maulidiat Debi, a form published in 1912 in Bombay, India,but no doubt composed much earlier. Knowledgeableinformants ~y that <strong>the</strong> Debi readings have been alteredby <strong>the</strong> addition <strong>of</strong> poems original to I.amu or materialfrom o<strong>the</strong>r forms <strong>of</strong> maulidi. 10 addition, Maulidi yaKiswahili is occasionally referred to as Maulidi ya Rama,<strong>the</strong> "shaking maulidi," referring to <strong>the</strong> movementsmade at <strong>the</strong> climax <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hymns. Some think Maulidiya Rama was once a distinct form <strong>of</strong> maulidi in itsown right, but most evidence indicates it is an earlierand perhaps derogatory name for what is called Maulidiya Kiswahili today.Maulidi ya Kiswahili is <strong>the</strong> only style <strong>of</strong> maulidi inI.amu in which Kiswahili is used. The language <strong>of</strong> sacredritual is Arabic, so that, even in Maulidi ya Kiswahil~<strong>the</strong> readings and many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hymns are in Arabic.Traditionally, new songs or verses were created on <strong>the</strong>spur <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> moment in <strong>the</strong> midst <strong>of</strong> heightened devotion,but this rarely happens today. Old favorites are <strong>the</strong>rule. Maulidi ya Kiswahili readings <strong>of</strong>ten occur in streetswhich have been set <strong>of</strong>f for <strong>the</strong> purpose by placingmats on <strong>the</strong> ground and enclosing <strong>the</strong> central area withropes tied to temporary poles. lights are strung between<strong>the</strong> poles and colored bits <strong>of</strong> cloth or paper are tiedto <strong>the</strong> ropes. At <strong>the</strong> height <strong>of</strong> a reading more than onehundred men and boys participate while o<strong>the</strong>rs ga<strong>the</strong>raround <strong>the</strong> perimeter.The participants sit in two long rows on <strong>the</strong> matsfacing each o<strong>the</strong>r. One row contains <strong>the</strong> readers ando<strong>the</strong>r leading religiOUS figures <strong>of</strong> ramu and <strong>the</strong> threematan players. Exact position in this row is determinedby age or respect for a person's status, especially in <strong>the</strong>religiOUS hierarchy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town. The o<strong>the</strong>r row containsyounger men and boys who at certain points in <strong>the</strong>ritual perform stylized dances on <strong>the</strong>ir knees, swayingfrom side to side. The drums accompany <strong>the</strong> hymns8but are silent during <strong>the</strong> readings. Each drum is tunedto a particular tension or pitch and each drummerplays a different rhythmiC pattern. The three drumstoge<strong>the</strong>r create a dynamic and forceful accompanimentto <strong>the</strong> singing.A Maulidi ya Kiswahili reading begins with fatiha,opening prayers. These are followed by <strong>the</strong> openinghymn which is <strong>the</strong> same at every reading. The first eightor nine verses are chanted by a teacher and <strong>the</strong> restare sung by various individuals, with <strong>the</strong> whole groupjoining in <strong>the</strong> chorus. Ano<strong>the</strong>r reading, chanted by one<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> leading teachers present follows <strong>the</strong> hymn.Readings and hymns alternate until <strong>the</strong> maqam, <strong>the</strong>verse which mentions <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet, isreached. At this point everyone rises and a series <strong>of</strong>hymns unique to this part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reading is sung. After<strong>the</strong> singing <strong>of</strong> five or six <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se hymns, everyone sitsdown again, final prayers called dua are said, andrefreshments <strong>of</strong> dates and c<strong>of</strong>fee are served. The wholereading usually takes about two and a half or three hours.The readings <strong>the</strong>mselves are well known to nearlyeveryone involved since <strong>the</strong>y occur at every performance.However, <strong>the</strong> leader can choose to leave out or includeparticular sections on a given night depending on <strong>the</strong>enthusiasm <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> men participating or o<strong>the</strong>r subjectivejudgments. The first two hymns are <strong>the</strong> same for everyreading, but <strong>the</strong> rest are chosen spontaneously byanyone who wishes to do so, merely by reciting <strong>the</strong>chorus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hymn as soon as it becomes apparent<strong>the</strong> reader has finished. The timing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entrance<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hymns is remarkable; <strong>the</strong>re is very little pausebetween readings and hymns. Direct competition <strong>of</strong>two hymns beginning at <strong>the</strong> same time is also rare.The hymns consist <strong>of</strong> a chorus which is sung byeveryone, and verses which are introduced spontaneouslyby various individuals. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> versesare familiar to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs and many join in with <strong>the</strong>original reciter before he finishes his lines. The versesfor a given hymn vary from reading to reading and areinterchangeable from hymn to hymn, so long as <strong>the</strong>y fit

<strong>the</strong> scansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> musical line. The number <strong>of</strong> versesalso varies from ten to as many as thirty. On occasion,someone chants a longer verse than usual in a stylecalled kukangaya, which means shaking. This style isborrowed from <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> maulidi called Maulidi yaKukangaya, which is now known only by a small number<strong>of</strong> older religious devouts. Examples occur in thisrecording, and <strong>the</strong> single performance <strong>of</strong> kukangayawitnessed in <strong>the</strong> field is excerpted on this record.At an indeterminate point <strong>the</strong> group begins to recite<strong>the</strong> last phrase or line <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hymn over and over again.This repetition is accompanied by synchronized bodymovements <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong> younger men in <strong>the</strong> facing row,who rise up onto <strong>the</strong>ir knees and quickly adjust <strong>the</strong>irpositions so that <strong>the</strong>ir shoulders are lightly touchingand <strong>the</strong>ir knees are aligned. The movements consist <strong>of</strong>gentle swaying from side to side and forvvard and backwith <strong>the</strong> arms held at angles in front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> body or withhands on shoulders. The duration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> repetitionsdepends again upon <strong>the</strong> enthusiasm <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> participants.Tension mounts during this chant, being encouragedby <strong>the</strong> intensity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> drums, until one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> leadersbegins a repetition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entire hymn and <strong>the</strong> wholegroup joins in. This ends that hymn and <strong>the</strong> nextreading begins.Maulidi ya Kiswahili is performed on <strong>the</strong> averageSide 2, Band 1Maulidi al-Habshi<strong>of</strong> once a week by one <strong>of</strong> two loosely organized groupsin <strong>the</strong> town, for no reason o<strong>the</strong>r than to praise <strong>the</strong>Prophet. It is believed that praises <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet resultin blessings on those who do it, and so <strong>the</strong> more <strong>of</strong>tenit is done, <strong>the</strong> better. BeSides, for <strong>the</strong> people <strong>of</strong> Iamu,it is an exciting addition to <strong>the</strong>ir regular prayers and<strong>the</strong>y take great satisfaction in a well executed reading.Malarl players accompanying Maulldl yaKlswabIUMaulidi al-Habshi is <strong>the</strong> most recent form <strong>of</strong>maulidi to be introduced into Iamu. All informantsagree that it was written by Ali ibn Muhammadal-Habshi, who taught in <strong>the</strong> Hadramaut on <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rncoast <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Saudi Arabian peninsula around <strong>the</strong> turn <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> twentieth century. One informant mentioned 1295a.h. (1915 a.d.) as an approximate date for <strong>the</strong> death<strong>of</strong> al-Habshi.Sources in Iamu knowledgeable about <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong>al-Habshi say that <strong>the</strong> ritual came to <strong>the</strong> East Africancoast because <strong>the</strong> Sultan <strong>of</strong> Hadramaut becamealarmed at <strong>the</strong> rising influence al-Habshi was gainingwith Bedouin tribesmen, who were attracted to histeachings because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> maulidi celebrations heregularly performed. In order to prevent his teachingsfrom being suppressed by governmental action,al-Habshi dispatched students to o<strong>the</strong>r parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Muslim world which had regular contact with <strong>the</strong>Hadrarnaut and probably contained Hadrami settlements.These included Java, Singapore, and Significantly,Iamu.Al-Habshi's maulidi was adopted for local use inIamu by a saintly ascetic teacher, Saleh ibn Alwy ibnAbdullah Jamal Al-lail, who has come to be called HabibSaleh, Habib being an honorific title meaning "beloved,"which is attached to <strong>the</strong> names <strong>of</strong> especially saintlyteachers after <strong>the</strong>ir deaths. Habib Saleh attracted manystudents both by his energetic teaching and through<strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> Maulidi al-Habshi as a devotional device.Because <strong>of</strong> his widespread influence as a teacher, hishouse came to be used by many people as a mosque.Some time before his death a new and larger mosque,called <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque, was built near his originalhouse. The Mosque-is nowone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most influential9schools <strong>of</strong> Muslim law and practice in all <strong>of</strong> East Africa.Hisdescendants and <strong>the</strong>ir pupils still practice Maulidial-Habshi on a regular basis. It is <strong>the</strong> form used for <strong>the</strong>annual celebration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet,organized and led by <strong>the</strong> teachers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque,and attended by thousands <strong>of</strong> visitors from alloverEast Africa.The performance <strong>of</strong> Maulidi al-Habshi resemblesMaulidi ya Kiswahili, containing regular readingsinterspersed with hymns, beginning with fatiha andending with dua. However, <strong>the</strong> readings or hymnsused in Maulidi al-Habshi never occur in Maulidi yaKiswahili or vice versa. In addition, <strong>the</strong> social organization<strong>of</strong> Maulidi al-Habshi readings is very different. In<strong>the</strong> first place, all <strong>the</strong> readings are done by teachersfrom <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque ra<strong>the</strong>r than by a variety <strong>of</strong>religiOUS leaders. Secondly, <strong>the</strong> teachers start all <strong>the</strong>hymns and recite <strong>the</strong> verses. The verses are regular foreach hymn, <strong>the</strong> same ones being used each time aparticular hymn is performed. O<strong>the</strong>r participants joinin repetitions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> verses and <strong>the</strong> chorus <strong>of</strong> hymnsand responses during <strong>the</strong> readings. The most activeparticipants in a Maulidi al-Habshi reading are studentsfrom <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque. O<strong>the</strong>rs attend <strong>the</strong> readings,but are less directly involved than <strong>the</strong>y are in Maulidi yaKiswahili readings.The hymns are accompanied by two matari, playedby young teachers from <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque. Occasionally,when <strong>the</strong> reading becomes very enthusiastic, afew boys or one or two men who participate in nearlyevery public maulidi reading in town beat <strong>the</strong> singleheadeddrum, kigoma, with a snapping motion thatenhances <strong>the</strong> sound <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> matari. This also happens onoccasion in a Maulidi ya Kiswahili reading. The boys,

who are seated facing <strong>the</strong>ir teachers and o<strong>the</strong>r dignitarieswho are attending <strong>the</strong> reading, dance with a subduedswaying and forward and back motion. The dancingis not as coordinated as in Maulidi ya Kiswahili readings,but when <strong>the</strong> fervor reaches its peak, it does allowconsiderable room for individual expression.After <strong>the</strong> maqam with its accompanying hymnsand <strong>the</strong> dua, a special song is <strong>of</strong>ten sung by one <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Riadha leaders. Occasionally, someone preaches asermon. Nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se features exists in MaulidiOccasionally, at a celebration that appears to <strong>the</strong>outside observer to be Maulidi al-Habshi because <strong>the</strong>Riadha sharifs are present, <strong>the</strong> readings being usedare actually those <strong>of</strong> Maulidi Barazanji, interspersedwith hymns from Maulidi al-Habshi. Maulidi Barazanjiis customarily read without instruments and with onlyone song immediately following <strong>the</strong> maqam. It most<strong>of</strong>ten occurs in private readings attended only by areligiOUS leader, <strong>the</strong> family sponsoring <strong>the</strong> event anda small number <strong>of</strong> invited friends. The occasion for <strong>the</strong>reading is <strong>of</strong>ten to fulfill a promise <strong>of</strong> praises to Allah ifa child is safely born, a business venture is successful,or someone's desire to make <strong>the</strong> pilgrimage to Meccahas become a reality. Maulidi Barazanji is commonlyused by women for private devotions. Some readings,especially those in honor <strong>of</strong> a deceased relative or anhonored teacher, have become annual events.The form <strong>of</strong> Maulidi Barazanji is similar toThis recording <strong>of</strong> Maulidi Diriji is unique. It wasperformed in Pate, a village which today sits in <strong>the</strong> middle<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ruins <strong>of</strong> a much larger and more powerful town,which was dominant in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn coastal regionuntil <strong>the</strong> seventeenth century. Maulidi Diriji wasplayed during a large wedding celebration in Pateto which many people from Siyu, ano<strong>the</strong>r town aboutan hour's walk away on <strong>the</strong> same island, were invited.It is likely that some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> drummers and "readers"were from Siyu.People said very little about Maulidi Dinji, exceptthat it was old and its performance was restricted toPate and Siyu. Its form is similar to o<strong>the</strong>r maulidiBand 2Maulldi BarazanjiBand 3Maulldi DlrljiBand 4Maulldi Sharaful Anam (Kukangaya)ya Kiswahili readings.During <strong>the</strong> month long celebration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Prophet, Maulidi al-Habshi is read in nearly everymosque in ramu. Maulidi ya Kiswahili is not read at allduring that month. After <strong>the</strong> celebration reaches itsclimax in <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque itself, <strong>the</strong> teachers andstudents travel to many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> towns on <strong>the</strong> islandssurrounding ramu, bringing <strong>the</strong> celebration andreading <strong>of</strong> Maulidi al-Habshi to those mosques as well.Maulidi ya Kiswahili and Maulidi al-Habshi, consisting<strong>of</strong> jatiha, four basic chapters which can be supplemented,and dua. The whole reading takes less than anhour. Refreshments after <strong>the</strong> reading are <strong>of</strong>ten veryelaborate since a small number <strong>of</strong> people attend and<strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reading is a reflection upon <strong>the</strong>generosity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> host.Maulidi Barazanji can be enlarged by <strong>the</strong> addition<strong>of</strong> sacred songs or hymns, but it has no hymns <strong>of</strong> its own.As is heard on <strong>the</strong> second volume in this set, <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong>Maulidi Barazanji readings combined with aparticular style <strong>of</strong> hymn, samai, is becoming verypopular in ramu. When it is used in this way, <strong>the</strong>readings are referred to by <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> musicalstyle ra<strong>the</strong>r than as maulidi. The recording <strong>of</strong> MaulidiBarazanji on this record is as it is most commonlyknown in ramu.consisting <strong>of</strong> chanted readings (recitations would bea better word, since <strong>the</strong>re is no book present) andhymns chanted by a number <strong>of</strong> men at <strong>the</strong> same time.The readings are longer than those contained inMaulidi ya Kiswahili or Maulidi al-Habshi and arerecited in a more songlike style. The whole formcould be said to consist <strong>of</strong> hymns alone, but withoutfur<strong>the</strong>r study, this judgement should be withheld.The hymns were accompanied by seven, or occasionallyeight, matan, which were larger than those used inramu and most <strong>of</strong> which did not have <strong>the</strong> metal ringsin <strong>the</strong>ir rims.Maulidi Sharajul Anam means "<strong>the</strong> model <strong>of</strong> mankind."It is a form that is known only to a few men inramu, and it was performed only once during <strong>the</strong> year<strong>of</strong> my stay <strong>the</strong>re. It is executed without instrumentalaccompaniment and is performed without referenceto any written sources. It consists <strong>of</strong> three parts calledWitina, Hamzia and Burdai. The whole <strong>of</strong> MaulidiSharajulAnam takes more than twelve hours to perform,ideally with each section performed from beginning toend without interruption. If time does not allow fora complete reading, <strong>the</strong> first section is interrupted in<strong>the</strong> middle and <strong>the</strong> second started. The performancefrom which this excerpt is taken lasted nearly sevenhours.10Ano<strong>the</strong>r name for Maulidi Sharajul Anam is MaulidiKukangaya, which refers to <strong>the</strong> "trembling" vocalquality used during <strong>the</strong> solo singing. The songs consist<strong>of</strong> sections chanted by <strong>the</strong> leader interspersed withrepetitions and choruses by <strong>the</strong> whole group. However,because very few know this form in its entirety, mostparticipants were able to join in only sporadically.In fact, <strong>the</strong> leader <strong>of</strong> this performance, which tookplace in <strong>the</strong> house <strong>of</strong> a deeply religiOUS man in ramu,was from Siyu. He brought a group <strong>of</strong> his students toassist him, and <strong>the</strong>se men contributed <strong>the</strong> bulk <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> group recitations.Occasionally kukangaya-style chanting is used duringa hymn. When this happens, <strong>the</strong> group activity

is interrupted while a leader chants. The texts usedmay be from Maulidi SharaJul Anam, although no onecould identify <strong>the</strong>m as such. Only <strong>the</strong> style <strong>of</strong> presentationwas recognized as kUkangaya. As was mentionedin relation to Maulidi ya Kiswahili, this style has carriedover into that form also.Maulidi SharaJul Anam is considered to be veryold. The latter two sections are said to have beencomposed by a teacher called al-Busry. KukangayaThe distinction between religiOUS and secular musicis indigenous to <strong>Lamu</strong>. It is not expressed in categoricalterms, but becomes apparent in <strong>the</strong> attitudes <strong>of</strong> peopletoward certain song styles and instruments and toward<strong>the</strong> context in which <strong>the</strong>y occur. In fact, with <strong>the</strong> exception<strong>of</strong> funeral processions, each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> musical formsheard on this disc occur in close association tornaulidi, <strong>the</strong> paramount religious musical form <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lamu</strong>.Samai is performed during <strong>the</strong> annual celebration<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet Muhammad by members <strong>of</strong>mosques o<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque, as anenthusiastic supplement to <strong>the</strong> central readings.Kasida and dhikiri are performed by <strong>the</strong> celebrantsSarnai in Arabic means "spiritual concert." Itoriginally was applied to mystical performances whichincluded song, dance and teaching. In <strong>Lamu</strong> <strong>the</strong> termis usually applied to a particular song style ra<strong>the</strong>r thanto an entire ritual, although sarnai performances <strong>of</strong>teninclude all three <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> original elements.Sarnai is said to have been introduced into <strong>Lamu</strong>by Habib Saleh, <strong>the</strong> same teacher who was responsiblefor <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> Maulidi al-Habshi in <strong>the</strong> religiouslife <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> community. It is usually played bymembers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Jamal al-Lail family, descendants <strong>of</strong>Habib Saleh, or by <strong>the</strong>ir students. Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> songsare thought to be very old, but o<strong>the</strong>rs are known tohave been composed by contemporary musicians,particularly two leading teachers from <strong>the</strong> Jamal alLail family.Sarnai songs are sung to <strong>the</strong> accompaniment <strong>of</strong> atleast three rnatari. In addition, several nai, smallKasida is an Arabic term which in <strong>Lamu</strong> is appliedto many hymns and songs sung in praise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet.It is not applied to <strong>the</strong> hymns used in any form <strong>of</strong>rnaulidi, nor to sarnai songs, although on occasiona kasida may be sung as an added hymn <strong>of</strong> praise orbe performed with rnalari and nai accompaniment.Kasida are sung by men, women and children at almostany time <strong>of</strong> day for no more reason than to enjoy <strong>the</strong>pleasure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> song. The origins <strong>of</strong> particular kasida arenot well known; <strong>the</strong>y are simply part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> repertoire<strong>of</strong> nearly every person in town.Contemporary musicians compose kasida forreligiOUS performance whenever <strong>the</strong> opportunity arises.Volume IIO<strong>the</strong>r Sacred <strong>Music</strong>Side 1, Band 1SarnaiBand 2Knsida11came to Siyu over three hundred years ago from <strong>the</strong>Comoro Islands, which have had contact with <strong>the</strong><strong>Lamu</strong> Archipelago for many centuries. It is said thatal-Busry composed Burdai, which refers to Muhammed'souter garment, during an illness when he had a vision <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Prophet covering him with his cloak. All <strong>the</strong> menfamiliar with Maulidi SharaJul Anam treasure it highlyand were delighted when a reading <strong>of</strong> it was performed.after a maulidi reading in order to continue <strong>the</strong> praises<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet for several more hours. ZeJealways occurat <strong>the</strong> high point <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> annual celebration.The instruments that appear in sacred musicalperformances are <strong>the</strong> rnatari, <strong>the</strong> tambourine-likeframe drums used in maulidi, nai, <strong>the</strong> small, end-blownflutes, and occasionally a very small single-headed i drum,ngorna. Sacred performances occur both inside andoutside mosques and in private homes.The combination <strong>of</strong> maulidi and <strong>the</strong>se o<strong>the</strong>r sacredforms rounds out <strong>the</strong> exciting religiOUS musicalrepertoire <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lamu</strong>, <strong>Kenya</strong>.end-blown flutes, are used. Originally <strong>the</strong>se fluteswere crafted out <strong>of</strong> bronze or wood, but most modemnai are plastiC or metal. They have five finger holeson <strong>the</strong> upper surface and a thumb hole underneath.The nai is placed on <strong>the</strong> mouth slightly <strong>of</strong>f center sothat <strong>the</strong> player is not blowing directly into <strong>the</strong> end,but is also not blOwing strictly across <strong>the</strong> opening. Thesound is not as clear as that <strong>of</strong> a recorder nor as "breathy"as many side-blown flutes. The clarity <strong>of</strong> sound dependsupon <strong>the</strong> mastery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> instruments by <strong>the</strong> player.Many young boys and men play <strong>the</strong> instrument in <strong>Lamu</strong>,but few have learned to control <strong>the</strong> sound.The singing style <strong>of</strong> sarnai songs resembles thatused in Maulidi al-Habshi readings. A leader singsverses while <strong>the</strong> group joins in <strong>the</strong> repeat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>choruses. Often during <strong>the</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> a modernsarnai song, a nai player executes a solo passage ina manner not unlike a jazz musician playing a riff.The song on this recording, Mzuri sana Nabia, isperformed by <strong>the</strong> composer, Hussein Badawy Jamalal-Lail. He is a well-known teacher and musician inEast Africa, having founded mosque colleges in Dar esSalaam, Tanzania and Arua, Uganda, where he wasresiding at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> recording. He has recordedseveral o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> his songs for public distribution todisseminate his appealing songs <strong>of</strong> praise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Prophet. This song was recorded on <strong>the</strong> porch <strong>of</strong> ahouse near <strong>the</strong> beautiful mosque college in Mambrui,<strong>Kenya</strong>. The college was founded in a coastal villagenear <strong>the</strong> resort town <strong>of</strong> Malindi by a son-in-law <strong>of</strong>Habib Saleh and is now led by Muhammad Sharif

Said, who pLayed <strong>the</strong> nai in <strong>the</strong> previous sarnai selection.The musical as well as religious contribution <strong>of</strong>this family to <strong>the</strong> East African Muslim community ispr<strong>of</strong>ound.Dhikiri is not regularly performed in Iamu. Severalinformants encouraged me to attend a dhikiri performance,but I could not locate one until one night, inMambrui, <strong>Kenya</strong>, I happened to be present whendhikiri was performed. The mosque in Mambrui is asatellite <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque in Iamu, being notedfor its musical rituals. Several <strong>of</strong> its teachers are outstandingmusicians.Dhikiri is known to occur in many parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Muslimworld. It is supposed to be based upon <strong>the</strong> Quranicinjunction, "Remember God with frequent remembranceand glorify Him morning and evening." Thismandate has evolved into recitations that involve <strong>the</strong>chanting <strong>of</strong> songs, accompanied by constant repetition<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> Allah. In some places <strong>the</strong>se recitationsreach a high pitch <strong>of</strong> intensity, due at least in part to<strong>the</strong> hyperventilation that results from aspirating "Allah"A zeJe is a procession, not a styLe <strong>of</strong> music, yet inlamu some music was used exclusively in zeJe. Hymnsfrom Mauiidi ya Kiswahili and kasida were alsoperformed, but exclusively zeJe songs were especiallypopular. They are performed in grand processionsthrough <strong>the</strong> streets <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town before crowds <strong>of</strong> womenand children and an occasional tourist who is attractedby <strong>the</strong> music. ZeJe usually precede and <strong>of</strong>ten followa ritual called ziara, which is a visit to <strong>the</strong> grave<strong>of</strong> an honored person to sing praises <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophetand to heap blessings upon <strong>the</strong> head <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> deceased.Some zeJe were more elaborate than o<strong>the</strong>rs, <strong>the</strong> largest<strong>of</strong> all being <strong>the</strong> one to <strong>the</strong> gravesite <strong>of</strong> Habib Saleh at<strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> mauiidi, <strong>the</strong> celebration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> birth<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet, sponsored by <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque. Themany visitors to Iamu for <strong>the</strong> festival contribute greatenthusiasm to <strong>the</strong> zeJe, each group performing musicassociated with its own village or school. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>most popular songs is a justification <strong>of</strong> singing mauiidi,directed at those who oppose such "noisy" displaysThe chants sung by a group <strong>of</strong> school boys whoprecede <strong>the</strong> procession and by <strong>the</strong> men bearing <strong>the</strong>c<strong>of</strong>fin <strong>of</strong> a deceased person to <strong>the</strong> burial ground areamong <strong>the</strong> most sensitive musical lines to be heardin Iamu. The contrast between praise and sorrow asexpressed in <strong>the</strong>se songs is a clear expression <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>religious convictions that permeate Iamu society and<strong>the</strong> tragedies that affect <strong>the</strong> lives <strong>of</strong> every man andwoman.The body <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> deceased is prepared for <strong>the</strong> burialat home and is <strong>the</strong>n taken to a mosque where familySide 2, Band 1DhikirlBand 2ZeJeBand 3Funeral Processionover and over again. On occasion, some may experienceseizures by <strong>the</strong> spirit or indulge in self-flagellationduring dhikiri.In Mambrui, <strong>the</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> dhikiri reached apeak <strong>of</strong> emotional intensity and one seizure did occur,but most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> performance was marked more by <strong>the</strong>involvement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> men in <strong>the</strong> joy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir praises andin <strong>the</strong> beauty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hymns. The soloist in <strong>the</strong> first songon this recording is Mohammad Khitami, a youngteacher, scholar and musician who was teaching inMalindi at <strong>the</strong> time. He is a son <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> leadingdescendants <strong>of</strong> Habib Saleh. The reciter and leader <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> second song is Hussein Badawy, <strong>the</strong> singer andcomposer <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> kasida heard on side 1, band 2, <strong>of</strong>this record. The combination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se two men toge<strong>the</strong>rwas electrifying.ZeJe being led by teachers dancing enthusiastically<strong>of</strong> overenthusiastic devotion. Today, <strong>the</strong>re are fewsuch opponents in Iamu, but in <strong>the</strong> past such resistancewas much more widespread. Songs like this one reflecta tension that was once a serious problem for <strong>the</strong>teachers and leaders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> community.and friends ga<strong>the</strong>r for prayers. Immediately <strong>the</strong>reafter<strong>the</strong> c<strong>of</strong>fin is borne to <strong>the</strong> graveyard for interment. Theboys walk first and are followed closely by <strong>the</strong> menwho are continuously replacing each o<strong>the</strong>r as pallbearers.At <strong>the</strong> grave <strong>the</strong> body is placed on a terracedug out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> grave, lying on its side facingMecca.After <strong>the</strong> burial special prayers and praises are sungei<strong>the</strong>r at <strong>the</strong> homes <strong>of</strong> close relatives or in mosques.Women close to <strong>the</strong> deceased must remain indoorsand mourn for at least three days.12

Volume IIISecular <strong>Music</strong>Secular music in lamu is clearly marked by <strong>the</strong>contexts in which it occurs. The first and most importantcontext is <strong>the</strong> wedding. Although marriage iscontracted in <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> a religious leader, <strong>of</strong>tenin a mosque, <strong>the</strong> great majority <strong>of</strong> events that occurduring a wedding are non-religious, being clearlyviewed as separate from <strong>the</strong> short, formal ceremonyitself.Men dance goma, kirumbizi and, on occasion,chama. Women process in <strong>the</strong> street canying giftsand dancing vugo and, on <strong>the</strong> morning after <strong>the</strong> consummation<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> marriage, <strong>the</strong>y carry msuwaki to <strong>the</strong>groom's home. During <strong>the</strong> previous night <strong>the</strong>y dancechakacha nonstop until dawn. Meanwhile, <strong>the</strong> menhave been listening to tarab while enjoying cups <strong>of</strong>tea.Chama and goma have also become associatedwith national patriotic celebrations, being performedduring public ceremonies and on <strong>the</strong> streets throughouta holiday.The instruments used in <strong>the</strong>se dance forms neverappear in mosques or during religiOUS ceremonies.This distinction alone is enough to clearly mark <strong>the</strong>separation <strong>of</strong> sacred and secular music in lamu.Coma is associated with Siyu and Faza. It was seenonce in lamu itself and that was when visitors from <strong>the</strong>seo<strong>the</strong>r towns performed it on <strong>the</strong> occasion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> annualcelebration <strong>of</strong> maulidi in front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Riadha Mosque.A space about twenty-five feet square is roped <strong>of</strong>ffor <strong>the</strong> performance. Chairs for special guests may beplaced inside <strong>the</strong> ropes on one side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> squarewhile <strong>the</strong> accompanying ensemble is placed on <strong>the</strong>opposite side. The instrumentation consists <strong>of</strong> a goma,a large single-headed drum standing on <strong>the</strong> ground onits own feet, a chapuo, an utasa and a zumari. O<strong>the</strong>robservers stand outside <strong>the</strong> ropes. The dancers, dressedin white gowns called kanzu, and small hats calledkojia, assemble in a line, Single file, shoulder toshoulder, along <strong>the</strong> third side. They each carry a caneabout four feet long, called bakora, in <strong>the</strong> right hand.The dance is divided into two parts as can bediscerned on <strong>the</strong> recording. During <strong>the</strong> first part <strong>the</strong>dancers quietly shift <strong>the</strong>ir weight from left to right whilegesturing with <strong>the</strong> canes. The dancer begins <strong>the</strong>sequence holding <strong>the</strong> cane straight up along his rightside. On <strong>the</strong> second half <strong>of</strong> a count <strong>of</strong> eight he lifts <strong>the</strong>cane up to a forty-five degree angle in front <strong>of</strong> himself.Simultaneously with a heavy thud being struck on <strong>the</strong>goma, he snaps his wrist and <strong>the</strong> cane away from hisbody. He <strong>the</strong>n brings it down again beside his body. Atintervals <strong>the</strong> group sings short songs.Side 1, Band 1GomaBand 2ChamaDuring <strong>the</strong> second half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dance <strong>the</strong> drum beatis faster, <strong>the</strong> gesture with <strong>the</strong> canes is not done, andno songs are sung. On ano<strong>the</strong>r occasion than <strong>the</strong> oneon this recording, various o<strong>the</strong>r gestures wereperformed with <strong>the</strong> canes, such as holding <strong>the</strong>mparallel to <strong>the</strong> ground in both hands in front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>body, or dropping <strong>the</strong> ends to <strong>the</strong> ground while leaningon <strong>the</strong>m.Throughout <strong>the</strong> entire dance a leader, kiongozt; walksback and forth in front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> line calling on <strong>the</strong>dancers to keep <strong>the</strong>mselves in order. The dancersmust keep <strong>the</strong>ir eyes fixed, not allowing <strong>the</strong>mselvesto be distracted. Friends may approach a dancer andplace a lighted cigarette or a piece <strong>of</strong> candy in his mouth,or pin money on his clothing. In addition, women mayline up outside <strong>the</strong> cleared area facing a horizontalpole which <strong>the</strong>y strike in time with <strong>the</strong> drumming.Sometimes Coma is performed by two groups at <strong>the</strong>same time, as a competition. The contest is one <strong>of</strong>endurance as <strong>the</strong> dance continues throughout <strong>the</strong>night. However, when Coma is performed as part <strong>of</strong> awedding celebration, it lasts only two or three hours.It is followed by a procession to <strong>the</strong> bride's house where<strong>the</strong> dancing continues a little longer and appropriatesongs are sung. This part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> performance is callednimbi herero.Chama is a men's dance which is indigenous toMatandoni, <strong>the</strong> small village on <strong>the</strong> opposite side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>island from lamu, near <strong>the</strong> mainland. It is <strong>the</strong> newestvillage on <strong>the</strong> island. Its inhabitants are principallydescendants <strong>of</strong> immigrants from towns north <strong>of</strong> lamu,especially Pate and Siyu. The people <strong>of</strong> Matandonihave carved out <strong>the</strong>ir place in <strong>the</strong> area by becomingshipbuilders, <strong>the</strong> town's location being ideal forpreparing a dhow and launching it on its maidenvoyage. The harbor is shallow and is nearly waterless atlow tide.The performance <strong>of</strong> chama on this recording wasdone by a group <strong>of</strong> visitors to a wedding in lamu.Seventeen men and boys from Matandoni performed13<strong>the</strong> dance in a vacant space on <strong>the</strong> waterfront. Theywere dressed in white kanzu and kojia, <strong>the</strong> traditionaldress <strong>of</strong> respect for religiOUS men. Each man was alsodecorated with sashes and garlands <strong>of</strong> flowers andcarried a sword or a cane which he waved in synchronywith <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs, not unlike <strong>the</strong> movements <strong>of</strong> goma. Afew wore belts with bells which jingled as <strong>the</strong>y danced.The men entered a roped-<strong>of</strong>f enclosure in a singleline, doing a shuffling step which required that <strong>the</strong> feetremain in <strong>the</strong> same relationship to each o<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>right foot always being in front. The left foot was crossedbehind <strong>the</strong> right, just touching <strong>the</strong> ground with <strong>the</strong> ball<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> foot. The line undulated as <strong>the</strong> men shuffledfirst to <strong>the</strong> right and <strong>the</strong>n to <strong>the</strong> left. After all had

entered and circumnavigated <strong>the</strong> enclosure, <strong>the</strong>y formeda line along one side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> square. At this point, a manemerged from <strong>the</strong> line and began to shout instructionsconcerning which song to sing, <strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>canes and coordination <strong>of</strong> movements. At one point,<strong>the</strong>y all laid <strong>the</strong>ir canes and swords on <strong>the</strong> ground,crossed <strong>the</strong>ir arms on <strong>the</strong>ir chests and swayed from sideto side in unison while continuing <strong>the</strong> gentle shuffle.The dance ended when <strong>the</strong> groom joined <strong>the</strong> lineand <strong>the</strong>y processed away from <strong>the</strong> enclosure and down<strong>the</strong> street, leading him home.The instrumental ensemble for chama consists <strong>of</strong>a large single-headed drum, simply called ngoma kuu,"<strong>the</strong> large drum," which is struck with <strong>the</strong> left hand andwith a stick held in <strong>the</strong> right hand; two vyapuo, smalldouble headed drums played with both hands; utasa, asmall metal plate placed inside a larger one and struckwith a knotted piece <strong>of</strong> rope called ziboj%; and azumari, an oboe-like double reed instrument with fivefinger holes.ZumarlTarab is <strong>the</strong> salon music <strong>of</strong> Uunu. It does not usuallyaccompany dancing, but ra<strong>the</strong>r is heard when men orwomen are lounging during a wedding celebration,passing time until ano<strong>the</strong>r important part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>festivities begin. It is a recent addition to <strong>the</strong> Uunurepertoire, being borrowed in part from Far Easternsources. None <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> instruments is indigenous to <strong>the</strong>East African coast. In fact, <strong>the</strong> harmonium, <strong>the</strong> twosmall Single-headed drums and <strong>the</strong> bongos are allimported from <strong>the</strong> Far East. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong>poems sung to tarab tunes are in kiswahili and conformto traditional Swahili verse forms. These consist <strong>of</strong> twoshort lines, <strong>the</strong> second <strong>of</strong> which is linked to o<strong>the</strong>r setsBand 3TarabSide 2, Band 1Ktrumbizi<strong>of</strong> lines by a rhyme in <strong>the</strong> last syllable. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>tunes are original to <strong>the</strong> poets, o<strong>the</strong>rs are borrowedfrom Indian movies which are frequently shown in Uunu.This performance by <strong>the</strong> Hararnbee <strong>Music</strong> Club waspart <strong>of</strong> a daily exhibition <strong>the</strong> young men presented in asmall room for <strong>the</strong> pleasure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir friends, <strong>the</strong>mselves,and an occasional tourist. The poem was composed byFamau, <strong>the</strong> singer, who accompanies himself on <strong>the</strong>harmonium with <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> group playing <strong>the</strong>rhythmic background. There are several o<strong>the</strong>r groupsplaying tarab in <strong>the</strong> vicinity <strong>of</strong> Uunu, all in competitionwith each o<strong>the</strong>r.Kirumbizi is a highly competitive stick dance whichusually occurs during wedding celebrations. Two menstep around <strong>the</strong> perimeter <strong>of</strong> a large clearing approximatelysixty feet across, carrying sticks in <strong>the</strong>ir righthands. The sticks, called mpweke, are over five feet long.At first <strong>the</strong> men walk in a stylized fashion paying littleattention to one ano<strong>the</strong>r, but soon <strong>the</strong>y turn andapproach <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> circle. Occasionally one or<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r strikes <strong>the</strong> ground with a stick. Finally onestrikes <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r's stick a hard blow and <strong>the</strong>n quicklyholds <strong>the</strong> stick and his o<strong>the</strong>r arm in front <strong>of</strong> his ownhead as if to parry a counterattack. Each man does thisuntil someone else enters <strong>the</strong> circle or until one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>combatants runs to <strong>the</strong> edge and tosses his stick to14someone else.Although <strong>the</strong> competition is basically friendly, oncein a while tempers flare. The lead drummer, playing avumi with two sticks, can control <strong>the</strong> intensity byreducing his intricate drum pattern to a Single beat.Whenever he does this, <strong>the</strong> contestants are supposed toback away and resume <strong>the</strong> circumlocution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>clearing. On one occasion, a drummer did not slowhis beat in time to prevent a few vicious blows frombeing administered. The surrounding crowd becamevery angry at <strong>the</strong> drummer, not <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fending dancer.The o<strong>the</strong>r instruments used in kirumbizi are achapuo, a goma, a zumari and an utasa. The vumiis <strong>the</strong> lead drum.

Vugo is a very popular women's dance, whichcustomarily is done as a procession through <strong>the</strong> streets<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town. During a wedding celebration, gifts aretaken from <strong>the</strong> groom's family to <strong>the</strong> bride's household.Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gifts are carried on cloth-covered plattersborne on <strong>the</strong> heads <strong>of</strong> important women <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> groom'sfamily. The procession is accompanied by a small bandconsisting <strong>of</strong> a trumpet, called a tarumbeta, and twodrums that can be carried by means <strong>of</strong> a sash thrown over<strong>the</strong> drummer's shoulder. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se is usually a chapuo;<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r is given various names such as vumi or kunda.Occasionally, a western bass drum, called beni, is usedwith a snare drum.The women in <strong>the</strong> procession carry cattle hornsIn lamu and <strong>the</strong> surrounding towns, chakacha isa women's dance. It is performed inside houses orin courtyards enclosed by mats hung from ropesstrung between poles which are especially placed for<strong>the</strong> dance. Men, except for <strong>the</strong> musicians, are notsupposed to witness a chakacha performance, andtraditionally, girls who have never married are notpermitted to perform, although today this prohibitionis breaking down.The instruments used in chakacha are two vumi,which are tuned a minor third apart by heating <strong>the</strong>heads, a chapuo and a long single-headed drum playedby a standing drummer with <strong>the</strong> drum between his legs.In addition, a trumpet and rattles, called kayamba, areused. Kayamba are most <strong>of</strong>ten made from gourds,Band 2VugoBand 3ChakachaBand 4Msuwakicalled pembe, which <strong>the</strong>y strike with sticks at variouspoints in <strong>the</strong>ir songs. One or two members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>procession act as song leaders; <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs join in assoon as <strong>the</strong>y recognize <strong>the</strong> song, or respond with loudexclamations. At frequent intervals <strong>the</strong> processionstops and <strong>the</strong> group forms a rough circle and dances,bowing down and lifting up <strong>the</strong> horns while striking<strong>the</strong>m more rapidly. On some occasions <strong>the</strong>se steps areprearranged to occur in front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> houses <strong>of</strong> relatives<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bride, while at o<strong>the</strong>r times <strong>the</strong>y occur whenevera leader decides it should happen.The songs sung during vugo processions refer to<strong>the</strong> bride, events during <strong>the</strong> wedding or advice onalthough on one occasion <strong>the</strong>y were made with emptytin cans and broken bottle glass.The dance is done in a circle with <strong>the</strong> womenfollowing each o<strong>the</strong>r closely in a counterclockwisedirection. Some put <strong>the</strong>ir hands on <strong>the</strong> shoulders <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> one in front while o<strong>the</strong>rs move independently.Each woman moves her feet, hips and shoulders intime with <strong>the</strong> music. The movements are not unlikesome latin American dances. Songs are sung occaSionally, usually in response to <strong>the</strong> trumpet player.Many songs can be used interchangeably in chakacha,vugo or kishuri, a dance not <strong>of</strong>ten seen today, but whichwas probably <strong>the</strong> forerunner <strong>of</strong> chakacha. Chakachadances last all night until time for <strong>the</strong> msuwaki justbefore dawn.Msuwaki is not a dance, but ra<strong>the</strong>r a procession,during which a gift, also called msuwaki, is broughtfrom <strong>the</strong> bride's family to <strong>the</strong> groom. The processionoccurs after <strong>the</strong> all-night chakacha. The gift consists<strong>of</strong> perfume, soap and o<strong>the</strong>r personal articles, but <strong>the</strong>essential factor is <strong>the</strong> poem that is sung as <strong>the</strong> processionarrives at <strong>the</strong> men's party. This is a personal song,composed especially for <strong>the</strong> occasion and sung by afew women or, if a tarab band is present, by one <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> musicians.15

For Add it ion a I I n form a t ion Abo u tFOLKWAYS RELEASES<strong>of</strong> Interestw r 'ite to'::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::'........................................................'::::::::::::::::::::::'....................................FolkVlays Recordsand Service Corp.632 BROADWAY, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10012LITHO IN USA ~ "