Adolescent Brain Development - the Youth Advocacy Division

Adolescent Brain Development - the Youth Advocacy Division

Adolescent Brain Development - the Youth Advocacy Division

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

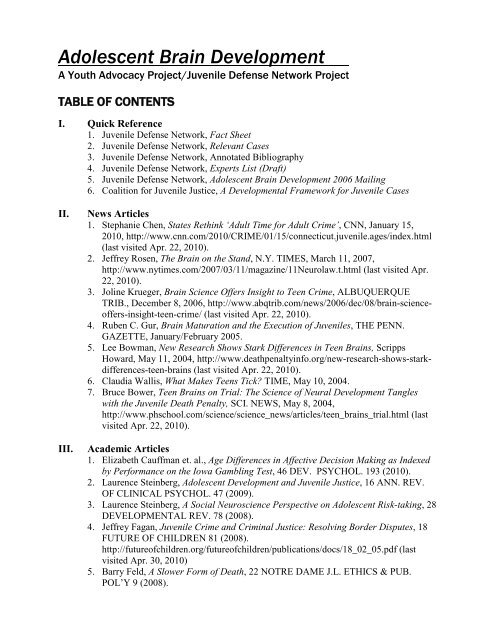

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

A <strong>Youth</strong> <strong>Advocacy</strong> Project/Juvenile Defense Network Project<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

I. Quick Reference<br />

1. Juvenile Defense Network, Fact Sheet<br />

2. Juvenile Defense Network, Relevant Cases<br />

3. Juvenile Defense Network, Annotated Bibliography<br />

4. Juvenile Defense Network, Experts List (Draft)<br />

5. Juvenile Defense Network, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> 2006 Mailing<br />

6. Coalition for Juvenile Justice, A <strong>Development</strong>al Framework for Juvenile Cases<br />

II. News Articles<br />

1. Stephanie Chen, States Rethink ‘Adult Time for Adult Crime’, CNN, January 15,<br />

2010, http://www.cnn.com/2010/CRIME/01/15/connecticut.juvenile.ages/index.html<br />

(last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

2. Jeffrey Rosen, The <strong>Brain</strong> on <strong>the</strong> Stand, N.Y. TIMES, March 11, 2007,<br />

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/11/magazine/11Neurolaw.t.html (last visited Apr.<br />

22, 2010).<br />

3. Joline Krueger, <strong>Brain</strong> Science Offers Insight to Teen Crime, ALBUQUERQUE<br />

TRIB., December 8, 2006, http://www.abqtrib.com/news/2006/dec/08/brain-scienceoffers-insight-teen-crime/<br />

(last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

4. Ruben C. Gur, <strong>Brain</strong> Maturation and <strong>the</strong> Execution of Juveniles, THE PENN.<br />

GAZETTE, January/February 2005.<br />

5. Lee Bowman, New Research Shows Stark Differences in Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s, Scripps<br />

Howard, May 11, 2004, http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/new-research-shows-starkdifferences-teen-brains<br />

(last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

6. Claudia Wallis, What Makes Teens Tick? TIME, May 10, 2004.<br />

7. Bruce Bower, Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s on Trial: The Science of Neural <strong>Development</strong> Tangles<br />

with <strong>the</strong> Juvenile Death Penalty, SCI. NEWS, May 8, 2004,<br />

http://www.phschool.com/science/science_news/articles/teen_brains_trial.html (last<br />

visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

III. Academic Articles<br />

1. Elizabeth Cauffman et. al., Age Differences in Affective Decision Making as Indexed<br />

by Performance on <strong>the</strong> Iowa Gambling Test, 46 DEV. PSYCHOL. 193 (2010).<br />

2. Laurence Steinberg, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Juvenile Justice, 16 ANN. REV.<br />

OF CLINICAL PSYCHOL. 47 (2009).<br />

3. Laurence Steinberg, A Social Neuroscience Perspective on <strong>Adolescent</strong> Risk-taking, 28<br />

DEVELOPMENTAL REV. 78 (2008).<br />

4. Jeffrey Fagan, Juvenile Crime and Criminal Justice: Resolving Border Disputes, 18<br />

FUTURE OF CHILDREN 81 (2008).<br />

http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/18_02_05.pdf (last<br />

visited Apr. 30, 2010)<br />

5. Barry Feld, A Slower Form of Death, 22 NOTRE DAME J.L. ETHICS & PUB.<br />

POL’Y 9 (2008).

6. Hillary Massey, 8 th Amendment and Juvenile Life Without Parole after Roper, 47 B.<br />

C. L. REV. 1083 (2006).<br />

7. Staci Gruber & Deborah Yurgelun-Todd, Neurobiology and <strong>the</strong> Law: A Role in<br />

Juvenile Justice? 3 OHIO ST. J. OF CRIM. L. 321 (2006).<br />

8. Margo Gardner & Laurence Steinberg, Peer Influence on Risk Taking, Risk<br />

Preference, and Risky Decision-Making in Adolescence and Adulthood: An<br />

Experimental Study, 41 DEV. PSYCHOL. 625 (2005).<br />

9. Press Release, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, <strong>Adolescent</strong><br />

<strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced Reward Anticipation, (Feb. 25, 2004).<br />

10. Laurence Steinberg & Elizabeth Scott, Less Guilty By Reason of Adolescence:<br />

<strong>Development</strong>al Immaturity, Diminished Responsibility, and <strong>the</strong> Juvenile Death<br />

Penalty, 58 AMER. PSYCHOL. 1009 (2003).<br />

IV. Reports and O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Advocacy</strong> Resources<br />

1. CHILD. LAW CTR. OF MASS., UNTIL THEY DIE A NATURAL DEATH:<br />

YOUTH SENTENCED TO LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE IN MASSACHUSETTS<br />

(2009).<br />

2. Wendy Paget Henderson, Life After Roper: Using <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> in<br />

Court, 11 A.B.A. CHILD. RTS 1, 1 (2009).<br />

3. Connie de la Vega & Michelle Leighton, Sentencing Our Children to Die in Prison:<br />

Global Law and Practice, 42 U.S.F.L. REV. 983 (2008).<br />

4. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, THE REST OF THEIR LIVES: LIFE WITHOUT<br />

PAROLE FOR YOUTH IN THE UNITED STATES IN 2008 (2008).<br />

5. A.B.A. RECOMMENDATION 105C, Mitigating Circumstances in Sentencing<br />

<strong>Youth</strong>ful Offenders (2008).<br />

6. Allstate Advertisement, WALL STREET JOURNAL, May 17, 2007.<br />

7. Less Guilty By Reason of Adolescence, Issue Brief (MacArthur Found. Res. Network<br />

on <strong>Adolescent</strong> Dev. & Juv. Just., 2006.<br />

http://www.adjj.org/downloads/6093issue_brief_3.pdf (last visited May 19, 2010)<br />

8. National Institute of Mental Health, Teenage <strong>Brain</strong>: A Work in Progress, 2001.<br />

V. Expert Testimonies/Briefs Addressing Expert Evidence<br />

1. Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Psychological Association, et al.,<br />

Graham v. Florida and Sullivan v. Florida (2009)<br />

2. Affidavit of Dr. Staci A. Gruber (2009)<br />

3. Declaration of Ruben C. Gur, Ph.D., Patterson v. Texas (2002)<br />

4. Testimony of Ruben C. Gur, Ph. D., People v. Clark, (Illinois)<br />

5. Testimony of David Fassler, M.D., New Hampshire State Legislature (2004)<br />

6. Interview with Deborah Yurgelun-Todd, PBS Frontline (2002)<br />

VI. Supreme Court Opinions<br />

1. Graham v. Florida – Majority opinion given by Justice Kennedy. Full opinion<br />

available at http://eji.org/eji/files/Decision%20in%20Graham.pdf.<br />

2. Graham v. Florida Quotes<br />

3. Roper v. Simmons – Majority opinion given by Justice Kennedy<br />

4. Atkins v. Virginia – Majority opinion given by Justice Stevens<br />

5. Thompson v. Oklahoma – Majority opinion given by Justice Stevens

VII. Legal Motions from MA<br />

1. Motion to dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2009<br />

2. Memo of law to dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2009<br />

3. Motion to Dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

4. Massachusetts Exhibit Appendix (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

5. Memo of Law to Dismiss (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

6. Motion to Dismiss YO (Ken King) – 2007<br />

7. Memo to Dismiss (Ken King) – 2007<br />

8. Motion for Evidentiary Hearing (Ken King) – 2007<br />

9. Motion to Dismiss (Patricia Downey) – 2005<br />

VIII. Legal Motions from O<strong>the</strong>r States<br />

1. Petitioner Brief, Sullivan v. Florida (2009)<br />

2. Petitioner Brief, Graham v. Florida (2009)<br />

3. Pennsylvania – Amici Brief<br />

4. Pennsylvania – Cover Sheet<br />

5. Alabama – Juvenile LWOP Brief<br />

6. Alabama – Sentencing Transcript<br />

7. Colorado – Flakes v. People<br />

8. Colorado – Apprendi Motion<br />

9. Colorado – Cert Petition<br />

10. Illinois – Motion Transfer Unconstitutional<br />

11. Illinois – Reply Brief<br />

12. Illinois – Appellant Brief<br />

13. New Mexico – Motion to Dismiss<br />

14. Washington, D.C. – Motion to Dismiss<br />

15. Washington, D.C. – Reply Letter<br />

16. Washington, D.C. – 2 nd Reply Letter<br />

IX. State Statutes<br />

1. 50 State Chart of JLWOP Law (National Conference of State Legislators)<br />

X. Helpful Websites<br />

1. List of helpful websites

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Quick Reference Fact Sheet<br />

Background<br />

• With <strong>the</strong> recent cases of Graham v. Florida (2010), Roper v. Simmons (2005), Atkins v. Virginia (2002), and<br />

Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), <strong>the</strong> topics of adolescent brain development and juvenile culpability have come to<br />

<strong>the</strong> forefront of juvenile criminal law. In Graham, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional to sentence<br />

juveniles convicted of non-homicide offenses to life without <strong>the</strong> possibility of parole. In Thompson and Roper, <strong>the</strong><br />

Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional to give <strong>the</strong> death penalty to juveniles (Thompson set <strong>the</strong> age limit to<br />

16, Roper to 18). In each of <strong>the</strong>se cases, <strong>the</strong> underlying rationale was that juvenile offenders tend to lack maturity<br />

(both socially and biologically), are more reckless, are more susceptible to peer pressure, and are more vulnerable<br />

to <strong>the</strong>ir surroundings than adults. In both Graham and Atkins, <strong>the</strong> topic of brain development played a crucial role<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Court determining that <strong>the</strong> sentence in question was not appropriate in light of <strong>the</strong> lessened culpability of<br />

<strong>the</strong> category of offenders challenging <strong>the</strong> sentence (juveniles in Graham, mentally retarded individuals in Atkins).<br />

Indeed, <strong>the</strong> Graham decision went as far as stating that “An offender’s age is relevant to <strong>the</strong> 8 th amendment, and<br />

criminal procedure laws that fail to take defendants’ youthfulness into account at all would be flawed.” Graham v.<br />

Florida, No. 08-7412, slip. op at 25, 560 U.S. __ (2010)<br />

• <strong>Adolescent</strong> brain development has become an increasingly accurate field of research in recent years due to <strong>the</strong><br />

development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedures. Prior to <strong>the</strong> use of MRI technology, <strong>the</strong> only<br />

major studies that had been performed involved post-mortem (cadaver) tissue, since X-rays and o<strong>the</strong>r means of<br />

testing were deemed potentially harmful to youth. MRI technology allows for <strong>the</strong> same subject to be tracked from<br />

infancy into adulthood. 1<br />

• States and <strong>the</strong> federal government generally do not recognize youth as being mature enough to handle many<br />

situations. For example, youth cannot drive until age 16 (varies by state, w/ most adopting restrictions on under 18<br />

drivers), or see rated R movies without adult supervision until <strong>the</strong>y are 17. They cannot vote, smoke, sign<br />

contracts, enter military services, or get married (varies by state) until age 18. And lastly, <strong>the</strong>y cannot drink until<br />

age 21. The implications of <strong>the</strong>se social norms indicates that society does not fully trust youth with many<br />

privileges, and thus do not consider <strong>the</strong>m as responsible as adults. 2<br />

Implications<br />

• As compared to adults, juveniles have a “‘lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility’”; <strong>the</strong>y<br />

“are more vulnerable or susceptible to negative influences and outside pressures, including peer pressure”; and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir characters are “not as well formed.” 3<br />

• “The evidence is strong that <strong>the</strong> brain does not cease to mature until <strong>the</strong> early 20s in those relevant parts that<br />

govern impulsivity, judgment, planning for <strong>the</strong> future, foresight of consequences, and o<strong>the</strong>r characteristics that<br />

make people morally culpable.” 4<br />

• “Neuroscientists have been able to demonstrate conclusively that mental maturation follows closely <strong>the</strong> time<br />

course of brain maturation. Thus, juveniles have to rely on <strong>the</strong> abilities of <strong>the</strong>ir still immature brains, and no<br />

amount of social intervention or self-motivation can appreciably influence <strong>the</strong> biological processes involved in<br />

brain maturation.” 5<br />

• “The cortical regions that are last to mature… are involved in behavioral facets germane to many aspects of<br />

criminal culpability. Perhaps most relevant is <strong>the</strong> involvement of <strong>the</strong>se brain regions in <strong>the</strong> control of aggression<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r impulses, <strong>the</strong> process of planning for long-range goals, organization of sequential behavior,<br />

consideration of alternatives and consequences, <strong>the</strong> process of abstraction and mental flexibility, and aspects of<br />

memory including ‘working memory.’… If <strong>the</strong> neural substrates of <strong>the</strong>se behaviors have not reached maturity<br />

before adulthood, it is unreasonable to expect <strong>the</strong> behaviors <strong>the</strong>mselves to reflect mature thought processes.”<br />

[Emphasis Added]. 6

Scientific Backing<br />

• Myelination is <strong>the</strong> main index by which brain maturity is measured. Myelin implies more mature, efficient<br />

connections, within <strong>the</strong> brain’s ‘gray matter.’ UCLA researchers performed a study comparing myelination of<br />

young adults aged 23-30 with adolescents aged 12-16. They found that <strong>the</strong>re was a stark contrast in <strong>the</strong><br />

myelination, especially in <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe and frontal cortex, <strong>the</strong> areas that relate to <strong>the</strong> maturation of cognitive<br />

processing and o<strong>the</strong>r ‘executive functions.’ 7<br />

• According to studies using advances in MRI technology, <strong>the</strong> area of <strong>the</strong> brain (frontal lobe) that is most related to<br />

decision making, planning, risk-assessment, judgment, and o<strong>the</strong>r factors generally associated with criminal<br />

culpability is also one of <strong>the</strong> last to fully mature. 8<br />

• According to research conducted by Lawrence Steinberg, a noted Professor of Psychology at Temple University,<br />

“risky behavior in adolescence is <strong>the</strong> product of <strong>the</strong> interaction between changes in two distinct neurobiological<br />

systems: a socioemotional system [which includes <strong>the</strong> amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex]. . . and a cognitive<br />

control system.” 9 Steinberg has noted that “changes in <strong>the</strong> socioemotional system at puberty may promote<br />

reckless, sensation-seeking behavior in early and middle adolescence, while <strong>the</strong> regions of <strong>the</strong> prefrontal cortex<br />

that govern cognitive control continue to mature over <strong>the</strong> course of adolescence and into young adulthood. This<br />

temporal gap between <strong>the</strong> increase in sensation seeking around puberty and <strong>the</strong> later development of mature selfregulatory<br />

competence may combine to make adolescence a time of inherently immature judgment. Thus, despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that in many ways adolescents may appear to be as intelligent as adults (at least as indexed by<br />

performance on tests of information processing and logical reasoning), <strong>the</strong>ir ability to regulate <strong>the</strong>ir behavior in<br />

accord with <strong>the</strong>se advanced intellectual abilities is more limited.” 10<br />

• According to a study at Harvard’s McLean Hospital, young teens tend to rely more on <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain<br />

(amygdala) responsible for fear and o<strong>the</strong>r ‘gut reactions’ when responding to o<strong>the</strong>r people’s emotions. Adults in<br />

contrast, more often utilize <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe, <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain which yields more reasoned perceptions. 11<br />

• According to a study performed by researches using MRI technology at <strong>the</strong> National Institute on Alcohol Abuse<br />

and Alcoholism, adolescents use lower activation of <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain that is “crucial for motivating behavior<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> prospect of rewards.” The study concludes that youth differ significantly in <strong>the</strong>ir responses to “rewarddirected<br />

behavior.” 12<br />

• The production of testosterone, a hormone that is closely associated with aggression, increases approximately<br />

tenfold in adolescent boys. 13<br />

1<br />

American Bar Association (ABA): Juvenile Justice Center. Adolescence, <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Legal Culpability. 2004.<br />

2<br />

Fagan, Jeffrey. “<strong>Adolescent</strong>s, Maturity, and <strong>the</strong> Law. The American Prospect. August, 2005.<br />

3<br />

Graham v. Florida, No. 08-7412, slip. op. at 17, 560 U.S. __ (2010) (quoted from Roper v. Simmons 543 U.S. at 569-570 (2005)).<br />

4<br />

Gur, Ruben C., Ph.D. Declaration of Ruben C. Gur. Patterson v. Texas. Petition for Writ of Certiorari to US Supreme Court, J. Gary<br />

Hart, Counsel. (2002).<br />

5<br />

Gur, op. cit.<br />

6<br />

Gur, op. cit.<br />

7<br />

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Teenage <strong>Brain</strong>: A Work in Progress. A brief overview of research into brain<br />

development during adolescence. 2001. See also: Sowell, Elizabeth, et al. In vivo evidence for post-adolescent brain maturation in<br />

frontal and striatal regions. Nature Neuroscience, 1999; 2(10): 859-861.<br />

8<br />

Fagan, op, cit. See also: Goldberg, Elkhonon. The Executive <strong>Brain</strong>, Frontal Lobes and <strong>the</strong> Civilized Mind, (2001).<br />

9<br />

Lawrence Steinberg, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Juvenile Justice, ANNU. REV. CLIN. PSYCHOL. 2009. 5:47–73 at 54.<br />

10<br />

Id. at 55.<br />

11<br />

NIMH, op cit. See also: Baird, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of facial affect recognition in children and adolescents.<br />

Journal of <strong>the</strong> American Academy of Child and <strong>Adolescent</strong> Psychiatry, 1999; 38(2): 195-9.<br />

12<br />

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced Reward Anticipation, 2004.<br />

13<br />

See Adams, Gerald R., Montemayor, Raymond, and Gullota, Thomas P., eds. Psychosocial <strong>Development</strong> during Adolescence. Sage<br />

Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. (1996).

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Quick Reference Relevant Cases<br />

GRAHAM v. FLORIDA (2010)<br />

In Graham, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court declared life without parole sentences for nonhomicide offenders under age 18<br />

unconstitutional. This decision marked <strong>the</strong> first time that <strong>the</strong> court declared a non-capital punishment to be cruel and<br />

unusual for an entire category of offenders. Although <strong>the</strong> holding of Graham arguably does not apply directly in<br />

Massachusetts, much of <strong>the</strong> language is broad enough that it can apply to juveniles who committed homicides as well as<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r offenses. Notably, <strong>the</strong>re is language indicating that life without parole sentences may not be appropriate for<br />

juveniles who “did not kill or intend to kill”, Graham v. Florida, No. 08-7412, slip. op. at 18, 560 U.S. __ (2010), as well<br />

as o<strong>the</strong>r language noting that “juvenile offenders cannot with reliability be classified among <strong>the</strong> worst offender” Id. at 17<br />

(quoting Thompson v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 853 (1988)) and that “[a]n offender’s age is relevant to <strong>the</strong> 8 th amendment, and<br />

criminal procedure laws that fail to take defendants’ youthfulness into account at all would be flawed.” Id. at 25. The<br />

court also noted that “[b]ecause ‘[t]he age of 18 is <strong>the</strong> point where society draws <strong>the</strong> line for many purposes between<br />

childhood and adulthood,’ those who were below that age when <strong>the</strong> offense was committed may not be sentenced to life<br />

without parole for a nonhomicide crime.” Id. at 24 (quoting Roper v. Simmons 543 U.S. at 574 (2005))<br />

ROPER v SIMMONS (2005)<br />

The March 2005 Supreme Court ruling in Roper finally outlawed <strong>the</strong> death penalty for juvenile offenders. Though <strong>the</strong><br />

majority opinion did not specifically mention recent scientific studies regarding differences between <strong>the</strong> adolescent brain<br />

and <strong>the</strong> adult brain, <strong>the</strong> American Psychological Association (APA) submitted a brief to <strong>the</strong> court in regards to <strong>the</strong> recent<br />

developments. Significantly, <strong>the</strong> scientific evidence presented by <strong>the</strong> APA was not challenged by ei<strong>the</strong>r side, something<br />

that had been done in prior decisions regarding <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty.<br />

ATKINS v VIRGINIA (2002)<br />

Atkins was <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court case that outlawed <strong>the</strong> death penalty for mentally retarded offenders, and set in motion <strong>the</strong><br />

ruling that was decided in Roper. Atkins is perhaps <strong>the</strong> most relevant case toward adolescent brain development<br />

specifically, as it <strong>the</strong> practice of executing mentally retarded offenders was declared unconstitutional under <strong>the</strong> Eighth<br />

Amendment (Cruel & Unusual Punishment). Justice Stevens delivered <strong>the</strong> Court’s Opinion, specifically noting that<br />

“because of [mentally retarded persons’] disabilities in areas of reasoning, judgment, and control of <strong>the</strong>ir impulses,<br />

however, <strong>the</strong>y do not act with <strong>the</strong> level of moral culpability that characterizes <strong>the</strong> most serious adult criminal conduct.”<br />

With adolescent brain development studies demonstrating that most adolescents do not fully develop <strong>the</strong> parts of <strong>the</strong> brain<br />

that deal specifically with reasoning, weighing of long-term goals, and instead tend to use <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain responsible<br />

for making “gut reactions,” <strong>the</strong> Atkins case has significant implications.<br />

PATTERSON v TEXAS (2002)<br />

In <strong>the</strong> case of Patterson v Texas, <strong>the</strong> Declaration of Ruben C. Gur, Ph.D. was submitted in appeals to bolster <strong>the</strong> argument<br />

that <strong>the</strong> defendant, a juvenile at <strong>the</strong> time of <strong>the</strong> accused crime, did not have a fully developed brain, and <strong>the</strong>refore was less<br />

culpable. The decision stated in part that “<strong>the</strong> evidence is strong that <strong>the</strong> brain does not cease to mature until <strong>the</strong> early 20s<br />

in those relevant parts that govern impulsivity, judgment, planning for <strong>the</strong> future, foresight of consequences, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

characteristics that make people morally culpable.” Dr. Gur’s findings were reiterated in <strong>the</strong> petition for writ of certiorari.<br />

The ruling on Patterson was held however, and <strong>the</strong> accused was executed by <strong>the</strong> State of Texas in August, 2002.<br />

THOMPSON v OKLAHOMA (1988)<br />

Thompson was <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court case where <strong>the</strong> age limit for <strong>the</strong> death penalty was officially moved up to 16. Although<br />

MRI technology was unavailable to demonstrate scientific reasoning for different brain development, <strong>the</strong> Thompson case<br />

is still vital as <strong>the</strong> court differentiated <strong>the</strong> culpability of a 15-year old from that of an adult in <strong>the</strong> context of a “heinous<br />

crime.” The decision on Thompson played a critical role as precedent for <strong>the</strong> findings in Roper.

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Annotated Bibliography<br />

I. Quick Reference<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, Fact Sheet<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, Relevant Cases<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, Annotated Bibliography<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, Experts List (Draft)<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> 2006 Mailing<br />

Coalition for Juvenile Justice, A <strong>Development</strong>al Framework for Juvenile Cases<br />

II. News Articles<br />

Stephanie Chen, States Rethink ‘Adult Time for Adult Crime’, CNN, January 15, 2010,<br />

http://www.cnn.com/2010/CRIME/01/15/connecticut.juvenile.ages/index.html (last visited Apr. 22,<br />

2010).<br />

• Discusses state efforts to raise age of automatic adult court jurisdiction, focusing on Connecticut,<br />

which changed age from 16 to 17. Also quotes psychologist Laurence Steinberg comparing <strong>the</strong><br />

teenage brain to “a car with a good accelerator but a weak brake.”<br />

Jeffrey Rosen, The <strong>Brain</strong> on <strong>the</strong> Stand, N.Y. TIMES, March 11, 2007,<br />

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/11/magazine/11Neurolaw.t.html (last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

• Discusses <strong>the</strong> use of neuroscience in criminal law generally and explores debate over <strong>the</strong><br />

relevance of neuroscience to law. Includes interviews with a lot of <strong>the</strong> experts who are at <strong>the</strong><br />

forefront of brain science as it applies to juvenile justice. Pages 3-4 of Section III include<br />

discussion of psychologist Ruben Gur’s expert testimony and <strong>the</strong> use of “neurolaw” in Roper.<br />

Ruben C. Gur, <strong>Brain</strong> Maturation and <strong>the</strong> Execution of Juveniles, THE PENN. GAZETTE,<br />

January/February 2005.<br />

• Article written by a psychiatrist describing <strong>the</strong> use of brain research in advocating against<br />

imposition of <strong>the</strong> death penalty on older adolescents.<br />

• “The evidence now is strong that <strong>the</strong> brain does not cease to mature until <strong>the</strong> early 20s in those<br />

relevant parts that govern impulsivity, judgment, planning for <strong>the</strong> future, foresight of<br />

consequences, and o<strong>the</strong>r characteristics that make people morally culpable. Therefore, from <strong>the</strong><br />

perspective of neural development, someone under 20 should be considered to have an<br />

underdeveloped brain. Additionally, since brain development in <strong>the</strong> relevant areas goes in phases<br />

that vary in rate and is usually not complete before <strong>the</strong> early to mid-20s, <strong>the</strong>re is no way to state<br />

with any scientific reliability that an individual 17-year-old has a fully matured brain (and should<br />

be eligible for <strong>the</strong> most severe punishment), no matter how many o<strong>the</strong>rwise accurate tests and<br />

measures might be applied to him at <strong>the</strong> time of his trial for capital murder.” (*4)

Joline Krueger, <strong>Brain</strong> Science Offers Insight to Teen Crime, ALBUQUERQUE TRIB., December 8,<br />

2006, http://www.abqtrib.com/news/2006/dec/08/brain-science-offers-insight-teen-crime/ (last visited<br />

Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

• Brief article discussing brain development and question of why adolescents act without thinking.<br />

“Cerebral construction is not complete until around ages 20 to 25, most scientists agree. The<br />

frontal lobe is one of <strong>the</strong> last areas of <strong>the</strong> brain to develop. In <strong>the</strong> adolescent brain, it's barely<br />

firing at all. Without <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe on board, it becomes physiologically harder for a teen to<br />

completely understand <strong>the</strong> future consequences of his or her emotional or impulsive actions,<br />

scientists contend.”<br />

Lee Bowman, New Research Shows Differences in Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s, Scripps Howard, May 11, 2004,<br />

http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/new-research-shows-stark-differences-teen-brains (last visited Apr. 22,<br />

2010).<br />

• Explains how while teens’ bodies maybe fully developed, <strong>the</strong>ir brains are nowhere near full<br />

maturity, especially in <strong>the</strong> areas related to culpability.<br />

• “Deborah Yurgelun-Todd of Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital in Boston has studied<br />

how teenagers and adults respond differently to <strong>the</strong> same images. Shown a set of photos of<br />

people's faces contorted in fear, adults named <strong>the</strong> right emotion, but teens seldom did, often<br />

saying <strong>the</strong> person was angry. … Adults used both <strong>the</strong> advanced prefrontal cortex and <strong>the</strong> more<br />

basic amygdala to evaluate what <strong>the</strong>y had seen; younger teens relied entirely on <strong>the</strong> amygdala,<br />

while older teens (top age in <strong>the</strong> group was 17) showed a progressive shift toward using <strong>the</strong><br />

frontal area of <strong>the</strong> brain. ‘Just because teens are physically mature, <strong>the</strong>y may not appreciate <strong>the</strong><br />

consequences or weigh information <strong>the</strong> same way as adults do,’ Yurgelun-Todd said. ‘Good<br />

judgment is learned, but you can't learn it if you don't have <strong>the</strong> necessary hardware.’”<br />

Claudia Wallis, What Makes Teens Tick? TIME, May 10, 2004,<br />

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,994126,00.html (last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

• Discusses <strong>the</strong> new technology, processes, and findings relating to brain development (as of 2004).<br />

Cites many of <strong>the</strong> leading brain researchers in <strong>the</strong> field.<br />

• “The very last part of <strong>the</strong> brain to be pruned and shaped to its adult dimensions is <strong>the</strong> prefrontal<br />

cortex, home of <strong>the</strong> so-called executive functions--planning, setting priorities, organizing<br />

thoughts, suppressing impulses, weighing <strong>the</strong> consequences of one's actions. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong><br />

final part of <strong>the</strong> brain to grow up is <strong>the</strong> part capable of deciding, I'll finish my homework and take<br />

out <strong>the</strong> garbage, and <strong>the</strong>n I'll IM my friends about seeing a movie.” (4)<br />

Bruce Bower, Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s on Trial: The Science of Neural <strong>Development</strong> Tangles with <strong>the</strong> Juvenile Death<br />

Penalty, SCIENCE NEWS, May 8, 2004,<br />

http://www.phschool.com/science/science_news/articles/teen_brains_trial.html (last visited Apr. 22,<br />

2010).<br />

• A good overview of <strong>the</strong> science involved and its application to <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty.<br />

• “‘Our objection to <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty is rooted in <strong>the</strong> fact that adolescents' brains function<br />

in fundamentally different ways than adults' brains do,’ says David Fassler, a psychiatrist at <strong>the</strong><br />

University of Vermont in Burlington and a leader of <strong>the</strong> effort to infuse capital-crime laws with<br />

brain science.<br />

Age-related brain differences pack a real-world wallop, in his view. ‘From a biological<br />

perspective,’ Fassler asserts, ‘an anxious adolescent with a gun in a convenience store is more<br />

likely to perceive a threat and pull <strong>the</strong> trigger than is an anxious adult with a gun in <strong>the</strong> same<br />

store.’” (1)

III. Academic Articles<br />

Elizabeth Cauffman et. al., Age Differences in Affective Decision Making as Indexed by Performance on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Iowa Gambling Test, DEV. PSYCHOL., 193 (2010).<br />

• Study showing that adolescents perform more poorly than adults in decision-making tasks where<br />

affective processing is involved and respond differently to rewards.<br />

• “[D]ecision making, which frequently precedes engaging in risk-taking behavior, indeed<br />

improves throughout adolescence and into young adulthood … this improvement may be due not<br />

to cognitive maturation but to changes in affective processing. Whereas adolescents may attend<br />

more to <strong>the</strong> potential rewards of a risky decision than to <strong>the</strong> potential costs, adults tend to<br />

consider both, even weighing costs more than rewards.<br />

This higher level of approach behavior during adolescence coupled with <strong>the</strong> lesser inclination<br />

toward harm avoidance may help explain increased novelty-seeking in adolescence, which can<br />

lead to various types of risk taking, including experimentation with drugs, unprotected sex, and<br />

delinquent activity.” (206)<br />

Laurence Steinberg, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Juvenile Justice, 16 ANN. REV. OF CLINICAL<br />

PSYCHOL. 47 (2008).<br />

• Excellent overview of adolescent development research. Outlines <strong>the</strong> implications of adolescent<br />

brain, cognitive, and psychosocial development on culpability, competence to stand trial, and<br />

impact of sanctions on adolescents.<br />

Laurence Steinberg, A Social Neuroscience Perspective on <strong>Adolescent</strong> Risk-taking, 28<br />

DEVELOPMENTAL REV. 78 (2008).<br />

• Summarizes brain development research and discusses why risk-taking behavior increases from<br />

childhood to adolescence and decreases from adolescence to adulthood.<br />

• “As a consequence of [neural transformations], relative to prepubertal individuals, adolescents<br />

who have gone through puberty are more inclined to take risks in order to gain rewards, an<br />

inclination that is exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> presence of peers. This increase in reward-seeking … has<br />

its onset around <strong>the</strong> onset of puberty, and likely peaks sometime around age 15, after which it<br />

begins to decline. Behavioral manifestations of <strong>the</strong>se changes are evident in a wide range of<br />

experimental and correlational studies using a diverse array of tasks and self-report instruments<br />

… and are logically linked to well-documented structural and functional changes in <strong>the</strong> brain.”<br />

(92)<br />

Jeffrey Fagan, Juvenile Crime and Criminal Justice: Resolving Border Disputes, 18 FUTURE OF<br />

CHILDREN 81 (2008). http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/18_02_05.pdf (last<br />

visited Apr. 30, 2010)<br />

• “Without exception <strong>the</strong> research evidence shows that policies promoting transfer of adolescents<br />

from juvenile to criminal court fail to deter crime among sanctioned juveniles and may even<br />

worsen public safety risks. The weight of empirical evidence strongly suggests that increasing<br />

<strong>the</strong> scope of transfer has no general deterrent effects on <strong>the</strong> incidence of serious juvenile crime or<br />

specific deterrent effects on <strong>the</strong> re-offending rates of transferred youth. In fact, compared with<br />

youth retained in juvenile court, youth prosecuted as adults had higher rates of rearrest for serious<br />

felony crimes such as robbery and assault. They were also rearrested more quickly and were<br />

more often returned to incarceration.” (105)<br />

Barry Feld, A Slower Form of Death, 22 NOTRE DAME J.L. ETHICS & PUB. POL’Y 9 (2008).<br />

• Argues that <strong>the</strong> diminished responsibility rationale in Roper should be extended by state<br />

legislatures to recognize youthfulness as a categorical mitigating factor in sentencing.

• “Although states may hold youths accountable for <strong>the</strong> harms <strong>the</strong>y cause, Roper explicitly limited<br />

<strong>the</strong> severity of <strong>the</strong> sentence a state could impose on <strong>the</strong>m because of <strong>the</strong>ir diminished<br />

responsibility. Even after youths develop <strong>the</strong> nominal ability to distinguish right from wrong,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir bad decisions lack <strong>the</strong> same degree of moral blameworthiness as those of adults and warrant<br />

less severe punishment.” (3)<br />

• “The court [in Roper] recognized that youths are more impulsive, seek exciting and dangerous<br />

experiences, and prefer immediate rewards to delayed gratification. They misperceive and<br />

miscalculate risks and discount <strong>the</strong> likelihood of bad consequences. They succumb to negative<br />

peer and adverse environmental influences. All of <strong>the</strong>se normal characteristics increase <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

likelihood of causing devastating injuries to <strong>the</strong>mselves and to o<strong>the</strong>rs. Although <strong>the</strong>y are just as<br />

capable as adults of causing great harm, <strong>the</strong>ir immature judgment and lack of self-control reduces<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir culpability and warrants less-severe punishment.” (6)<br />

• “Roper’s diminished responsibility rationale provides a broader foundation to formally recognize<br />

youthfulness as a categorical mitigating factor in sentencing. Because adolescents lack <strong>the</strong><br />

judgment, appreciation of consequences, and self-control of adults, <strong>the</strong>y deserve shorter sentences<br />

when <strong>the</strong>y cause <strong>the</strong> same harms. <strong>Adolescent</strong>s’ personalities are in transition, and it is unjust and<br />

irrational to continue harshly punishing a fifty- or sixty-year-old person for <strong>the</strong> crime that an<br />

irresponsible child committed several decades earlier.” (10)<br />

Hillary Massey, 8 th Amendment and Juvenile Life Without Parole after Roper, 47 B. C. L. REV. 1083<br />

(2006).<br />

• Argues for elimination or limitation of JLWOP based on proportionality review and diminished<br />

culpability of juveniles.<br />

• “The psychosocial research shows strong differences between adolescents and adults that<br />

implicate assessments of culpability. Researchers have identified four psychosocial factors that<br />

affect <strong>the</strong> way adolescents make decisions, including whe<strong>the</strong>r to commit a crime or an antisocial<br />

act: peer influence, attitude toward risk, future orientation, and capacity for self-management. In<br />

one study, adolescents on average scored significantly lower than adults on <strong>the</strong>se factors and<br />

displayed less sophistication in decision making. Although individual levels of <strong>the</strong>se factors are<br />

more predictive of antisocial decision making than chronological age alone, researchers found<br />

that <strong>the</strong> period between ages sixteen and nineteen is an important transition point in psychosocial<br />

development.” (1090)<br />

Staci Gruber & Deborah Yurgelun-Todd, Neurobiology and <strong>the</strong> Law: A Role in Juvenile Justice? 3 OHIO<br />

ST. J. OF CRIM. L. 321 (2006).<br />

• Summarizes adolescent neurobiology research and argues that brain differences due to immature<br />

development, like brain differences due to disease, be taken into account in justice system.<br />

• “[N]eurobiological studies … indicate that <strong>the</strong> cerebral cortex undergoes a dynamic course of<br />

metabolic maturation that persists at least until <strong>the</strong> age of eighteen. … Younger, less cortically<br />

mature adolescents may be more at risk for engaging in impulsive behavior than <strong>the</strong>ir older peers<br />

for two reasons. First, <strong>the</strong>ir developing brains are more susceptible to <strong>the</strong> neurological effects of<br />

external influences such as peer pressure. Second, <strong>the</strong>y may make poor decisions because <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

cognitively less able to select behavioral strategies associated with self-regulation, judgment, and<br />

planning that would reduce <strong>the</strong> effects of environmental risk factors for engaging in such<br />

behaviors.” (330)<br />

• Steps for defense attorneys to take to understand a client’s state of mind and baseline levels of<br />

functioning are listed on p. 332.

Margo Gardner & Laurence Steinberg, Peer Influence on Risk Taking, Risk Preference, and Risky<br />

Decision-Making in Adolescence and Adulthood: An Experimental Study, 41 DEV. PSYCHOL. 625<br />

(2005).<br />

• Study finding that exposure to peers during a risk taking task doubled <strong>the</strong> amount of risky<br />

behavior among mid-adolescents (with a mean age of 14), increased it by 50 percent among<br />

college undergraduates (with a mean age of 19), and had no impact at all among young adults.<br />

• “[T]he presence of peers makes adolescents and youth, but not adults, more likely to take risks<br />

and more likely to make risky decisions.” (634)<br />

Press Release, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced<br />

Reward Anticipation, (Feb. 25, 2004). http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/feb2004/niaaa-25.htm (last visited<br />

May 19, 2010)<br />

• Discusses how adolescents’ brains respond differently to incentives (risk/reward). Cites MRI<br />

study conducted on 12-17 year old and 22-28 year old subjects.<br />

• “<strong>Adolescent</strong>s show less activity than adults in brain regions that motivate behavior to obtain<br />

rewards, according to results from <strong>the</strong> first magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study to examine<br />

real-time adolescent response to incentives.” (1)<br />

Laurence Steinberg & Elizabeth Scott, Less Guilty By Reason of Adolescence: <strong>Development</strong>al Immaturity,<br />

Diminished Responsibility, and <strong>the</strong> Juvenile Death Penalty, 58 AMER. PSYCHOL. 1009 (2003).<br />

• Explains from a medical standpoint how adolescent brain development affects culpability<br />

• “In general, adolescents use a risk-reward calculus that places relatively less weight on risk, in<br />

relation to reward, than that used by adults.” (1012)<br />

• “The vast majority of adolescents who engage in criminal or delinquent behavior desist from<br />

crime as <strong>the</strong>y mature.” (note 13, at 1015)<br />

IV. Reports and O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Advocacy</strong> Resources<br />

CHILDREN’S LAW CTR. OF MASS., UNTIL THEY DIE A NATURAL DEATH: YOUTH<br />

SENTENCED TO LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE IN MASSACHUSETTS (2009).<br />

• Study examining <strong>the</strong> imposition of juvenile life without parole in Massachusetts. Includes<br />

discussion of MA law, adolescent brain and developmental research, statistics and vignettes about<br />

<strong>the</strong> youth sentenced to LWOP in MA, discussion of <strong>the</strong> experiences of youth in adult prisons,<br />

analysis of economic costs of <strong>the</strong> sentencing practice, and a summary of global sentencing<br />

practices with respect to juvenile life without parole.<br />

Wendy Paget Henderson, Life After Roper: Using <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> in Court, 11 CHILD.<br />

RTS 1, 1 (2009).<br />

• <strong>Advocacy</strong> guide for using adolescent brain research in litigation prepared by A.B.A. Children’s<br />

Rights Litigation Committee. Issues addressed include competence, sentencing mitigation,<br />

duress and coercion, differences in assessing reasonableness and recklessness for juveniles, and<br />

mental responsibility.<br />

Connie de la Vega & Michelle Leighton, Sentencing Our Children to Die in Prison: Global Law and<br />

Practice, 42 U.S.F.L. REV. 983 (2008).<br />

• Examines international norms and practices regarding juvenile life without parole.<br />

• “The United States is <strong>the</strong> only violator of <strong>the</strong> international human rights standard prohibiting<br />

juvenile LWOP sentences. With thousands of juveniles serving LWOP sentences, and none<br />

serving such sentences in <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong> United States is <strong>the</strong> only country now violating<br />

this standard” (990)

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, THE REST OF THEIR LIVES: LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE FOR YOUTH<br />

IN THE UNITED STATES IN 2008 (2008).<br />

• Executive Summary of report examining juvenile life without parole in <strong>the</strong> U.S. Discusses<br />

crimes that can lead to LWOP, sentencing practices across <strong>the</strong> states, racially discriminatory<br />

sentencing, violent experiences that youth have had in prison, international standards regarding<br />

JLWOP, and recommendations for legislatures. Updated in 2008.<br />

A.B.A. RECOMMENDATION 105C, Mitigating Circumstances in Sentencing <strong>Youth</strong>ful Offenders<br />

(2008).<br />

• ABA Recommendation calling for less punitive sentences for children under 18, recognition of<br />

youth as a mitigating factor in sentencing, and parole or early release eligibility for youthful<br />

offenders.<br />

• “The American Bar Association has a long history of recognizing that youth under 18 who are<br />

involved with <strong>the</strong> justice system should be treated differently than those who are 18 or older.<br />

• The ABA’s overall approach to juvenile justice policies has been and continues to be to strongly<br />

protect <strong>the</strong> rights of youthful offenders within all legal processes while insuring public safety.<br />

Central to this ABA premise is <strong>the</strong> understanding that youthful offenders have lesser culpability<br />

than adult offenders due to <strong>the</strong> typical behavioral characteristics inherent in adolescence. It is<br />

understood that <strong>the</strong>y can and do commit delinquent and criminal acts that have an impact on<br />

public safety, but <strong>the</strong>se actors none<strong>the</strong>less are developmentally different. They are not adults and<br />

do not have fully-formed adult characteristics.” (Introduction)<br />

Allstate Advertisement, WALL STREET JOURNAL, May 17, 2007.<br />

• Insurance ad advocating for graduated driver licensing laws on <strong>the</strong> basis of adolescent brain<br />

development. The ad pictures an image of a brain with a car-shaped hole and reads, “Why do<br />

most 16-year-olds drive like <strong>the</strong>y’re missing a part of <strong>the</strong>ir brain? BECAUSE THEY ARE.”<br />

• “Even bright, mature teenagers sometimes do things that are ‘stupid.’<br />

But when that happens, it’s not really <strong>the</strong>ir fault. It’s because <strong>the</strong>ir brain hasn’t finished<br />

developing. The underdeveloped area is called <strong>the</strong> dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex. It plays a<br />

critical role in decision making, problem solving and understanding future consequences of<br />

today’s actions. Problem is, it won’t be fully mature until <strong>the</strong>y’re into <strong>the</strong>ir 20s.”<br />

Less Guilty By Reason of Adolescence, Issue Brief (MacArthur Found. Res. Network on <strong>Adolescent</strong> Dev.<br />

& Juv. Just., 2006. http://www.adjj.org/downloads/6093issue_brief_3.pdf (last visited May 19, 2010)<br />

- Explains “immaturity gap” in adolescents who are intellectually mature but more impulsive,<br />

short-sighted, and susceptible to peer influence than adults, and argues that juveniles are less<br />

culpable than adults because of <strong>the</strong>ir immaturity. Advocates for a separate system for juvenile<br />

offenders.<br />

ABA Online: Adolescence, <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Legal Culpability, (2004)<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/Adolescence.pdf (.pdf. format)<br />

• Concise overview of <strong>the</strong> implications of adolescent brain development science on <strong>the</strong> juvenile<br />

justice system<br />

National Institute of Mental Health, Teenage <strong>Brain</strong>: A Work in Progress (2001).<br />

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/teenbrain.cfm<br />

• Brief article summarizing some of <strong>the</strong> teenage brain studies performed by 2001.<br />

• “Using functional MRI (fMRI), a team led by Dr. Deborah Yurgelun-Todd at Harvard's McLean<br />

Hospital scanned subjects' brain activity while <strong>the</strong>y identified emotions on pictures of faces<br />

displayed on a computer screen. Young teens, who characteristically perform poorly on <strong>the</strong> task,

activated <strong>the</strong> amygdala, a brain center that mediates fear and o<strong>the</strong>r "gut" reactions, more than <strong>the</strong><br />

frontal lobe. As teens grow older, <strong>the</strong>ir brain activity during this task tends to shift to <strong>the</strong> frontal<br />

lobe, leading to more reasoned perceptions and improved performance. Similarly, <strong>the</strong> researchers<br />

saw a shift in activation from <strong>the</strong> temporal lobe to <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe during a language skills task,<br />

as teens got older.” (2)<br />

V. Expert Testimony/Briefs<br />

Petitioner Brief, Graham v. Florida (2010)<br />

Successful Supreme Court brief arguing against juvenile life without parole for non-homicide offenses<br />

committed by juveniles under 18. Cites Roper and adolescent brain research extensively.<br />

Petitioner Brief, Sullivan v. Florida (2009)<br />

Brief arguing against juvenile life without parole for non-homicide offense committed by 13-year-old.<br />

Cites Roper and adolescent brain research extensively.<br />

Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Psychological Association, et al., Sullivan and Graham (2009)<br />

http://www.abanet.org/publiced/preview/briefs/pdfs/07-08/08-7412_PetitionerAmCu4HealthOrgs.pdf<br />

The APA and o<strong>the</strong>rs’ amicus brief in Sullivan and Graham that cites heavily to new brain science<br />

Testimony of David Fassler, M.D., New Hampshire State Legislature (2004)<br />

http://ccjr.policy.net/relatives/22020.pdf (.pdf format)<br />

Testimony given to <strong>the</strong> State Legislature of New Hampshire in efforts to outlaw <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty<br />

in <strong>the</strong> state (relies heavily on brain development arguments)<br />

Declaration of Ruben C. Gur, Ph.D., Patterson v. Texas (2002)<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/Gur%20affidavit.pdf (.pdf format)<br />

Declaration in Patterson v. Texas (juvenile death penalty case) citing heavily upon recent science<br />

regarding adolescent brain development<br />

VI. Supreme Court Opinions<br />

Graham v. Florida – 560 U.S. ____ (2010)<br />

Supreme Court case that declared life without parole unconstitutional for juvenile offenders under 18<br />

convicted of nonhomicide crimes.<br />

Quotes from Graham v. Florida<br />

Potentially useful language from <strong>the</strong> Graham decision.<br />

Roper v. Simmons – 543 U.S. 551 (2005)<br />

Supreme Court case that declared <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty unconstitutional and discusses <strong>the</strong><br />

developmental differences between juveniles under age 18 and adults.<br />

Atkins v. Virginia – 536 U.S. 304 (2002)<br />

Supreme Court case that declared <strong>the</strong> death penalty for mentally retarded persons unconstitutional (uses<br />

arguments of brain development)<br />

Thompson v. Oklahoma – 487 U.S. 815 (1988)<br />

Supreme Court case that declared <strong>the</strong> death penalty illegal for youth under <strong>the</strong> age of 16.

VII. Legal Motions from MA<br />

Motion to dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2009<br />

Memo of law to dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) –<br />

2009<br />

Motion to Dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

Massachusetts Exhibit Appendix (Jack Cunha) –<br />

2007<br />

VIII. Legal Motions from O<strong>the</strong>r States<br />

Petitioner Brief – Sullivan v. Florida<br />

Petitioner Brief – Graham v. Florida<br />

Pennsylvania – Amici Brief<br />

Pennsylvania – Cover Sheet<br />

Alabama – Juvenile LWOP Brief<br />

Alabama – Sentencing Transcript<br />

Colorado – Flakes v. People<br />

Colorado – Apprendi Motion<br />

IX. State Statutes<br />

Memo of Law to Dismiss (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

Motion to Dismiss YO (Ken King) – 2007<br />

Memo to Dismiss (Ken King) – 2007<br />

Motion for Evidentiary Hearing (Ken King) –<br />

2007<br />

Motion to Dismiss (Patricia Downey) – 2005<br />

Colorado – Cert Petition<br />

Illinois – Motion Transfer Unconstitutional<br />

Illinois – Reply Brief<br />

Illinois – Appellant Brief<br />

New Mexico – Motion to Dismiss<br />

Washington, D.C. – Motion to Dismiss<br />

Washington, D.C. – Reply Letter<br />

Washington, D.C. – 2 nd Reply Letter<br />

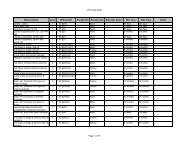

Chart showing how and where juvenile life without parole is imposed across 50 states (National<br />

Conference of State Legislatures)<br />

Regularly updated state-by-state statistics on juvenile life without parole:<br />

http://www.law.usfca.edu/jlwop/resourceguide.html<br />

X. Helpful Websites<br />

Laurence Steinberg Publications (Website)<br />

http://www.temple.edu/psychology/lds/publications.htm<br />

Laurence Steinberg is a professor of Psychology at Temple University and a leading authority on<br />

psychological development during adolescence. Pdf versions of his publications are available on this site.<br />

Campaign for <strong>the</strong> Fair Sentencing of <strong>Youth</strong> (Website)<br />

http://www.endjlwop.org/<br />

The national campaign to end juvenile life without parole includes information about state sentencing<br />

practices and an extensive advocacy resource bank, including a section on adolescent brain research.

Most of <strong>the</strong> materials for Sullivan and Graham are available on <strong>the</strong> site, and <strong>the</strong> site is updated regularly<br />

with new resources.<br />

American Bar Association: Juvenile Justice Committee (Website)<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/<br />

The ABA’s Juvenile Justice website has a myriad of resources regarding adolescent brain development,<br />

and simple searches of brain development will yield current articles as well as information about <strong>the</strong><br />

Graham, Roper, and Atkins cases. The best way to navigate this site is by using <strong>the</strong> search function.<br />

PBS Frontline: Inside <strong>the</strong> Teenage <strong>Brain</strong> (Website/Program)<br />

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/teenbrain/<br />

This 2002 PBS Frontline specifically dealt with recent technology in <strong>the</strong> field of neuroimaging as it<br />

relates to adolescent brain development. The show gives an in-depth overview of <strong>the</strong> science and<br />

technology involved, includes interviews, and discusses some of <strong>the</strong> implications of <strong>the</strong> findings. Watch<br />

<strong>the</strong> entire show online, read <strong>the</strong> transcript, and read interviews w/ experts.<br />

MacArthur Foundation on <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Juvenile Justice (Website)<br />

http://www.adjj.org/content/index.php<br />

The MacArthur Foundation’s website has numerous documents, briefs, and PowerPoint presentations all<br />

discussing adolescent development (immaturity, cognitive abilities, risk-assessment, etc). The Foundation<br />

consists of some of <strong>the</strong> leading researches in <strong>the</strong> field of adolescent development as it relates to <strong>the</strong><br />

juvenile justice system.<br />

National Juvenile Justice Network (Website)<br />

http://njjn.org/<br />

The National Juvenile Justice Network website posts a wealth of resources, including its own research<br />

publications, legislative material, and publications on a variety of issues in juvenile justice.

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

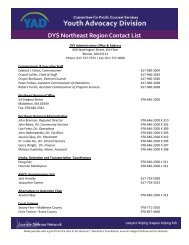

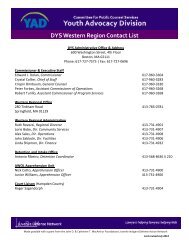

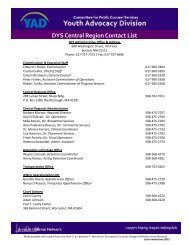

Quick Reference Experts List (DRAFT)<br />

BAIRD, ABIGAIL, Ph.D.<br />

Neuroscientist – Dartmouth College<br />

Phone: (603) 646-9022 Fax: Email: abigail.a.baird@dartmouth.edu<br />

Website: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~psych/people/faculty/a-baird.html<br />

Worked with Deborah Yurgelun-Todd (below) on <strong>the</strong> 1999 study involving teens’ identification of<br />

emotions. In subsequent experiments, Dr. Baird learned that teens’ correct recognition of emotional<br />

responses significantly improved when <strong>the</strong> faces were those of people <strong>the</strong>y knew, suggesting that<br />

adolescents are more prone to pay attention to things that are more closely related to <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

BJORK, JAMES, Ph.D.<br />

Researcher – National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.<br />

Phone:<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email:<br />

Researcher at <strong>the</strong> National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism who used MRI technology to scan<br />

brains of 12 adolescents (aged 12-17) and 12 adults (aged 22-28) comparing <strong>the</strong>ir responses to simulated<br />

situations involving risks and rewards. The study found that youth tend to use lower activation of <strong>the</strong> part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> brain associated with motivating behavior toward <strong>the</strong> prospect of rewards. Dr. Bjork notes that <strong>the</strong><br />

study “may help to explain why so many young people have difficulty achieving long-term goals.”<br />

FASSLER, DAVID, M.D.<br />

Clinical Associate Professor – UVM Medical School, Psychiatry Dept.<br />

Phone: (802) 865-3450<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email: David.Fassler@uvm.edu<br />

<strong>Adolescent</strong> psychiatrist who testified on behalf of <strong>the</strong> American Psychiatric Association in Nevada in<br />

2003 and New Hampshire in 2004 to try and persuade <strong>the</strong> state legislatures to abolish <strong>the</strong> death penalty<br />

for juveniles. Both states abolished <strong>the</strong> practice after Dr. Fassler’s testimony, which used studies<br />

regarding <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong> adolescent brain as part of <strong>the</strong> basis of his argument.<br />

GIEDD, JAY, M.D.<br />

Neuroscientist – National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)<br />

Phone: (301) 435-4517<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email: GieddJ@intra.nimh.nih.gov<br />

Has performed extensive research involving almost 2,000 kids and adolescents using MRI technology<br />

that demonstrates that adolescent brains are still developing and are different from fully-developed adult<br />

brains. Dr. Giedd has created records of each of <strong>the</strong> youth he has scanned, taking MRI every two years,<br />

showing <strong>the</strong> growth and development of <strong>the</strong> brain over <strong>the</strong> years. His research shows that especially in<br />

early adolescence, <strong>the</strong> brain is undergoing drastic changes.

GOLDBERG, ELKHONON Ph.D.<br />

Clinical Professor – NYU Medical School<br />

Phone: (212) 541 6412 Fax: (212) 765 7158 Email: eg@elkhonongoldberg.com<br />

Website: http://www.elkhonongoldberg.com/<br />

Authored The Executive <strong>Brain</strong>, Frontal Lobes and <strong>the</strong> Civilized Mind, (2001), which contends that <strong>the</strong><br />

frontal lobe is responsible for decision making, planning, cognition, judgment, and o<strong>the</strong>r behavior skills<br />

associated with criminal culpability. While Dr. Goldberg is not juvenile specific, his findings are<br />

extremely important when combined with work that proves that <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe is still undergoing<br />

significant changes during adolescence.<br />

GOGTAY, NITIN M.D.<br />

Psychiatrist - NIMH<br />

Phone: (301) 443-4513<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email:<br />

Led a team that used MRI technology to study youth ages 4 to 21 to prove that <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe is one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> last areas of <strong>the</strong> brain to fully mature. The frontal lobe is thought to be <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain most<br />

closely associated to factors related to criminal culpability such as decision making, risk assessment, etc.<br />

GRISSO, THOMAS, Ph.D.<br />

Professor – UMASS Medical School, Psychiatry Dept.<br />

Phone: (508)-856-3625 Fax: (508)-856-6426 Email: Thomas.Grisso@umassmed.edu<br />

Website: http://www.umassmed.edu/cmhsr/faculty/Grisso.cfm<br />

Nationally known juvenile forensics expert and co-editor of <strong>Youth</strong> on Trial, (2000), which argues in part<br />

that <strong>the</strong> psychological development of adolescents affects <strong>the</strong>ir abilities to comprehend <strong>the</strong> juvenile<br />

justice process, and also makes <strong>the</strong>m less morally culpable. The book specifically takes on <strong>the</strong> issue of<br />

“Adult Time for Adult Crime.”<br />

GRUBER, STACI, Ph.D.<br />

Neuropsychologist – McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA<br />

Phone: (617)-855-3238<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email:<br />

GUR, RUBEN, Ph.D.<br />

Neuropsychologist – University of Pennsylvania Hospital<br />

Phone: (215) 662-2915 Fax: Email: gur@bbl.med.upenn.edu<br />

Website: http://www.med.upenn.edu/ins/faculty/gur.htm<br />

Submitted declaration in Patterson v. Texas (2002), stressing that adolescents were less culpable than<br />

adults. Discusses how <strong>the</strong> parts of <strong>the</strong> brain most related to criminal culpability are also <strong>the</strong> latest parts to<br />

develop.

SCOTT, ELIZABETH, J.D.<br />

Professor – University of Virginia Law School<br />

Phone: (434) 924-3217 Fax: (804) 924-7536 Email: es@virginia.edu<br />

Website: http://www.law.virginia.edu/lawweb/faculty.nsf/FHPbI/5417<br />

Co-director and founder of <strong>the</strong> Center for Children, Families and Law and law professor at University of<br />

Virginia who specializes in juvenile and family law. Author of “Blaming <strong>Youth</strong>,” (2002), an essay which<br />

uses scientific research to demonstrate why juveniles are not as culpable from a legal perspective.<br />

SOWELL, ELIZABETH, Ph.D.<br />

Professor – UCLA Medical School, Neurology Dept.<br />

Phone: (310) 206-2101 Fax: Email: esowell@loni.ucla.edu<br />

Website: http://www.neurology.ucla.edu/faculty/SowellE.htm<br />

Led studies of brain development from adolescence to adulthood. Found that during adolescence, <strong>the</strong><br />

frontal lobe of <strong>the</strong> brain (<strong>the</strong> part that relates to <strong>the</strong> maturation of cognitive processing and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

‘executive functions), undergoes <strong>the</strong> most significant changes. The study found that <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe was<br />

<strong>the</strong> last part of <strong>the</strong> brain to fully develop, and thus while adolescent brains may be similar to adults, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

differ in <strong>the</strong>ir abilities to reason.<br />

TOGA, ARTHUR, Ph.D.<br />

Professor – UCLA Medical School, Neurology Dept.<br />

Phone: (310)206-2101 Fax: (310)206-5518 Email: toga@loni.ucla.edu<br />

Website: http://www.neurology.ucla.edu/faculty/TogaA.htm<br />

Neuroimaging specialist who worked with NIMH to render MRI scans into a 4-D time-lapse model<br />

demonstrating <strong>the</strong> evolution of a child’s brain into adulthood (<strong>the</strong> 4 th dimension is rate of change). The<br />

model demonstrates <strong>the</strong> growth and movement of different brain matter as children grow into adults.<br />

YURGELUN-TODD, DEBORAH Ph.D.<br />

Neuropsychologist – McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA<br />

Phone: (617)-855-3238<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email:<br />

Performed a study comparing what parts of <strong>the</strong> brain adolescents and adults use when responding to<br />

emotions. The study concluded that adolescents tend to rely on <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain responsible for “gut<br />

reactions,” in contrast to adults who more often use <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain responsible for more rational (not<br />

based on emotional responses) decisions.

Limbic System<br />

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Understanding <strong>the</strong> Parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong><br />

Amygdala<br />

The Adult <strong>Brain</strong><br />

The Frontal Lobe, often called <strong>the</strong> “command center” of <strong>the</strong> brain, is <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain<br />

that controls <strong>the</strong> decision making process for adults, including long-term planning, riskassessment,<br />

impulse control, and o<strong>the</strong>r behaviors associated with criminal culpability. It is<br />

also one of <strong>the</strong> last parts of <strong>the</strong> brain to fully mature (in <strong>the</strong> early 20s). 1 This late maturation<br />

process suggests that adolescents are not as capable as adults of weighing long-term<br />

consequences, and evaluating risk-assessment.<br />

The Prefrontal Cortex is responsible for cognitive processing, problem solving, and<br />

emotional control in adults. There is a stark contrast in brain maturation (Myelination)<br />

between youth aged 12-16 and young adults (23-30), especially in <strong>the</strong> Frontal Lobe and<br />

Prefrontal Cortex. 2 This difference suggests that adults are more capable of controlling <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

emotions and making more rational decisions than adolescents.<br />

The <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong><br />

The Limbic System regulates hormonal processing, which is overly active in adolescents, 3<br />

and also is responsible for handling emotional reactions. <strong>Adolescent</strong>s tend to use <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

Limbic System more often in <strong>the</strong> decision making process, since <strong>the</strong>ir Frontal Lobes are<br />

not fully developed, which results in adolescents making more decisions based on<br />

emotional reactions ra<strong>the</strong>r than reasoning, weighing of long term consequences, or<br />

planning. 4<br />

The Amygdala, part of <strong>the</strong> Limbic System, is responsible for impulse reactions, emotional<br />

reactions, fear, and is also used in <strong>the</strong> decision-making process of adolescents.<br />

Developing adolescents tend to use <strong>the</strong>ir Amygdala when responding to o<strong>the</strong>r people’s<br />

emotions, yielding more reactionary, less reasoned perceptions of situations than adults. 5<br />

Juvenile Defense Network ~ Lawyers Helping Lawyers Helping Kids

Footnotes:<br />

_______________________________________________________________________<br />

1. Fagan, Jeffrey. “Adoescents, Maturity, and <strong>the</strong> Law.” The American Prospect. August, 2005.<br />

2. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Teenage <strong>Brain</strong>: A Work in Progress. 2001.<br />

3. <strong>Adolescent</strong>s going through puberty experience increased hormone levels. For example, <strong>the</strong> production of testosterone, a<br />

hormone closely associated with aggression, increases approximately tenfold in boys. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse<br />

and Alcoholism (NIAAA). <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced Reward Anticipation. 2004.<br />

4. McNamee, Rebecca. An Overview of <strong>the</strong> Science of <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong>. Presented at <strong>the</strong> Coalition for<br />

Juvenile Justice Annual Conference. 2006.<br />

5. NIMH. Id.<br />

Images Adapted From:<br />

_______________________________________________________________________<br />

1. PBS: The Secret Life of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/brain/<br />

2. Amygdala/Limbic System: http://www.memorylossonline.com/glossary/amygdala.html<br />

Online Resources:<br />

_______________________________________________________________________<br />

1. ABA: Adolescence, <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Legal Culpability<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/Adolescence.pdf<br />

2. American Psychologist: Less Guilty by Reasons of Adolescence<br />

http://ccjr.policy.net/cjedfund/resourcekit/Psychology_Less_Guilty.pdf<br />

3. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced Reward Anticipation.<br />

http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/feb2004/niaaa-25.htm<br />

4. National Institute of Mental Health: Imaging Study Shows <strong>Brain</strong> Maturing.<br />

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/press/prbrainmaturing.cfm<br />

5. PBS Frontline: Inside <strong>the</strong> Teenage <strong>Brain</strong><br />

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/teenbrain/<br />

6. Roper v. Simmons: Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Bar Association, et al.<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/simmons/aba.pdf<br />

7. Roper v. Simmons: Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Medical Association, et al.<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/simmons/ama.pdf<br />

8. Roper v. Simmons: Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Psychological Association, et al.<br />

http://www.apa.org/psyclaw/roper-v-simmons.pdf<br />

9. Science Magazine: Crime, Culpability, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong><br />

http://www.wpic.pitt.edu/research/lncd/papers/ScienceLunaOct2004.pdf<br />

10. Science News: Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s on Trial.<br />

http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20040508/bob9.asp<br />

11. Juvenile Defense Network: Roper v. Simmons and ways to incorporate it into your practice.<br />

http://www.youthadvocacyproject.org/pdfs/Roper%20fact%20sheet.pdf<br />

This project is supported by Grant # 2005 JF-FX 0055 awarded by <strong>the</strong> Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U.S.<br />

Department of Justice to <strong>the</strong> Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety Programs <strong>Division</strong> and subgranted to <strong>the</strong> Committee for Public Counsel Services.<br />

Points of view in this document are those of <strong>the</strong> author(s) and do not necessarily represent <strong>the</strong> official position or policies of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Department of Justice or <strong>the</strong><br />

Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety Programs <strong>Division</strong>.<br />

Juvenile Defense Network<br />

<strong>Youth</strong> <strong>Advocacy</strong> Project/CPCS<br />

Ten Malcolm X Blvd.<br />

Roxbury, MA 02119<br />

Tel: (617) 445-5640<br />

http://www.youthadvocacyproject.org/jdn.htm

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Implications in <strong>the</strong> Courtroom<br />

Adolescence has long been known as a time of significant psychosocial development. Recent advances in<br />

fMRI (functional MRI) technology have been critical in understanding adolescence as a crucial period of brain<br />

development. 1 Since <strong>the</strong> science is relatively new, we do not know how it will affect juvenile justice<br />

jurisprudence; a system focused on behavior not anatomy. Science supports <strong>the</strong> notion that anatomy affects<br />

behavior, and as juvenile defenders we need to educate <strong>the</strong> court in this area and use <strong>the</strong> research to<br />

advocate for our clients.<br />

Below are some suggestions on how to use this new brain information in your practice. There are many ways<br />

to utilize <strong>the</strong> research, from pre-trial issues to jury instructions. However, counsel should be aware that <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is no case law in Massachusetts addressing <strong>the</strong> admissibility of brain science testimony and, <strong>the</strong>refore, be<br />

prepared for any objections. We also suggest counsel submit a separate jury instruction on adolescent brain<br />

development in every juvenile trial to highlight that kids are different.<br />

<strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> Facts & Implications in <strong>the</strong> Courtroom:<br />

Adolescence is a time of significant neurobiological and psychosocial development, meaning that adolescent<br />

behaviors are less predictive than adult behavior of personality characteristics and future behavior. 2 This fact<br />

can be used in disposition/sentencing to argue that children can be rehabilitated and that long, and<br />

especially adult sentences, are not consistent with research that indicates adolescents behavior can change<br />

and prior behavior is not as predictive of future behavior. Additionally, <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>ir brains are not fully<br />

developed can also be used when seeking relief from <strong>the</strong> sex offender registry, a consequence which<br />

neglects to consider that youth can change <strong>the</strong>ir “criminal” behavior.<br />

<strong>Adolescent</strong> brains undergo a second wave of significant development during <strong>the</strong> teen years, (primarily<br />

concentrated in <strong>the</strong> Frontal Lobe), meaning that <strong>the</strong>ir capacity to make decisions, use judgment, respond to<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs’ emotions, and assess long-term consequences is immature, and still developing. 3 This fact can be<br />

used as a trial issue and as part of jury instructions. Since adolescents tend to respond to certain stimuli<br />

using <strong>the</strong>ir Amygdala, <strong>the</strong> youth, it can be argued, may not be able to form <strong>the</strong> requisite intent for <strong>the</strong> crime<br />