Bulletin - Summer 1979 - North American Rock Garden Society

Bulletin - Summer 1979 - North American Rock Garden Society

Bulletin - Summer 1979 - North American Rock Garden Society

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

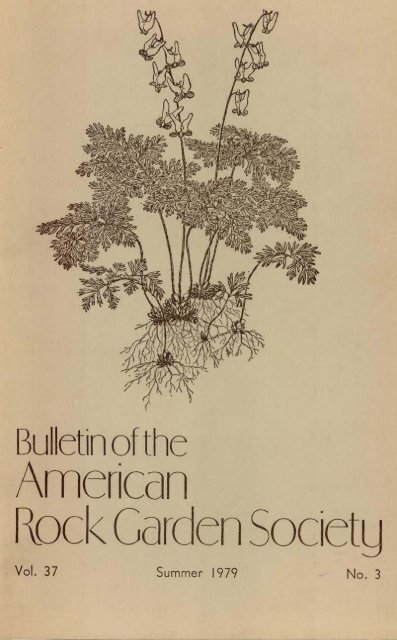

<strong>Bulletin</strong> of the<strong>American</strong><strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong>Vol. 37 <strong>Summer</strong> <strong>1979</strong>

The <strong>Bulletin</strong>Editor EmeritusDR. EDGAR T. WHERRY, Philadelphia, Pa.EditorLAURA LOUISE FOSTER, Falls Village, Conn. 06031Assistant EditorHARRY DEWEY, 4605 Brandon Lane, Beltsville, Md. 20705Contributing Editors:Roy DavidsonAnita KistlerH. Lincoln Foster Owen PearceBernard HarknessH. N. PorterLayout Designer: BUFFY PARKERBusiness ManagerANITA KISTLER, 1421 Ship Rd., West Chester, Pa. 19380Contents Vol. 37 No. 3 <strong>Summer</strong> <strong>1979</strong>Two Eastern Dicentras—H. Lincoln Foster 105A Dicentra Variant—Mercer Reeves Hubbard 107We're in the Chips—Boyd C. Kline with Edward Huggins 109A Small Glamorous Shrub: Fothergilla gardenii—Mrs. Ralph Cannon 115Lester Rowntree 116Nomocharis in Massachusetts—Ronald A. Beckwith 117Cyclamen in Containers—Brian Halliwell 123The Turfing Lilies—John Osborne 125A New Hybrid Saponaria—Zdenek Zvolanek and Jaroslav Klima 126A Good Tempered Synthyris—Edith Dusek 127Victoria <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong>s—Sybil McCulloch 129The Evolution of a <strong>Garden</strong> . . . and <strong>Garden</strong>er—Florence Free 133Award Winners—<strong>1979</strong>: Sallie Allen, Laura Louise Foster, H. Lincoln Foster 136Book Reviews: Manual of Alpine Plants by Will Ingwersen; Wildflowers of the<strong>North</strong>eastern States by Frederick W. Case 139Notes from Alaska: Botanizer's Bonanza at Eagle Summit—Helen A. White 142Of Cabbages and Kings: A Fresh Approach—Henry Fuller; Clematis Texensis—Pam Harper; Cutting Dates—Dorothea De Vault; Poison Ivy Cure;Cyclamen <strong>Society</strong> 144In Praise of <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong>ing—Charles Gordon Post 150Front Cover Picture—Dicentra cucullaria—Laura Louise Foster, Falls Village, CTPublished quarterly by the AMERICAN ROCK GARDEN SOCIETY, incorporated under the lawsof the State of New Jersey. You are invited to join. Annual dues (<strong>Bulletin</strong> included) are:Ordinary Membership, $9.00; Family Membership (two per family), $10.00; Overseas Membership,$8.00 each to be submitted in U.S. funds or International Postal Money Order;Patron's Membership, $25; Life Membership, $250. Optional 1st cL delivery, U.S. and Canada,$3.00 additional annually. Optional air delivery overseas, $6.00 additional annually. Membershipinquiries and dues should be sent to Donald M. Peach, Secretary, Box 183, Hales Corners,Wi. 53130. The office of publication is located at 5966 Kurtz Rd., Hales Corners, Wi. 53130.Address editorial matters pertaining to the <strong>Bulletin</strong> to the Editor, Laura Louise Foster, FallsVillage, Conn. 06031. Address advertising matters to the Business Manager at 1421 Ship Rd.,West Chester, Pa. 19380. Second class postage paid in Hales Corners, Wi. and additionaloffices. <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> (ISSN 0003-0864.)

Vol. 37 <strong>Summer</strong> <strong>1979</strong> No. 3<strong>Bulletin</strong> of the<strong>American</strong><strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> SooetnTWO EASTERN DICENTRASH. LINCOLN FOSTERFalls Village, ConnecticutDrawings by Laura Louise FosterFleeting but elegant are the two speciesof dicentra that grace the earlyspring flora of Eastern United States:D. cucullaria and D. canadensis.Similar they are to the point of confusion,with only slight above groundand yet conspicuous below ground differences.D. cucullaria, most commonly knownas Dutchman's Breeches, has green fernyfoliage early in the spring toppedby a one sided raceme of nodding,white, dancing flowers most curiouslyformed. The structure of the blossomis intricately arranged with the fourpleated and folded petals assuming suchunlikely postures that their basic poppyrelationship is not only concealed butflouted. Instead of raising a cup ofcrinkled petals upward to bask in thesun D. cucullaria wraps two of its petalsupward to form puffed wide-spreadinghorns — yes, like an upside-down pairof Dutch pantaloons, suspended by analmost invisible pedicel and filled onlywith air. Two other petals curl downto form a pouch that expands at themouth into two cupped wings tippedwith gold. Wrapped within are the functionalstamens and pistils. Theseblossoms dance for a week or so inearliest spring above the lacy platformof deeply cut, slightly glaucus greenfoliage. Then, after this ballet, all collapseswith remarkable suddenness; theballarinas sink as they sway, their gar-105

ments shrivelling to tawdry brown.Black seeds within the horned podsof the ovary extension harden andglaze. The pod bursts. The seeds extrude.The foliage fades from greento yellow, glimmering down gently toleave no remnants and the undergroundbase of this ballet of blossoms is calledupon to carry on the life processesbelow ground and unseen until anotherperformance the following spring.These underground parts consist of ashort root-stock bearing a cluster ofpinkish-white rice-like tubers, huddledinto a scaly bulb.In Dicentra canadensis the subterraneanrhizome carries loosely held, golden,grain-like tubers. It is this featurethat gives this plant its colloquial name,Squirrel Corn. The foliage is quite im-Dicentra canadensispossible to distinguish from that ofDutchman's Breeches though it appearsa bit later in the spring and persistsfor a week or two longer. SquirrelCorn blossoms are carried in a mannersimilar to those of Dutchman's Breeches,but the individual flowers, thoughsuperficially similar, are quitedistinctively shaped. Here the upwardpointed furled petals form shorter morerounded spurs, parallel rather thandiverent, looking, indeed, like the erectears of a baby rabbit, and the wingson either side of the mouth are pinkishrather than yellow as in D. cucullaria.These two dicentras, similar as theyare, possess other less obvious differences.Though their ranges overlapto a large extent, they do not hybridizeas they have different chromosomenumbers and there appear to be subtledifferences in their site preferences.Dicentra cucullaria has a slightlymore extensive range south and west,extending from Quebec west to <strong>North</strong>Dakota and south to Alabama andMissouri with a curious disjunctpopulation, distinguished as var. occidentalis,in Oregon, Washington andIdaho. Where its range overlaps withthat of the less widespread D. canadensisthe two are occasionally found growingtogether in rich woodlands, butin all state floras Squirrel Corn isdescribed as much rarer than Dutchman'sBreeches.Neither of these dicentras is commonlyencountered in rock gardensdespite their intrinsic beauty and thefact that most rock garden texts listat least D. cucullaria. For some yearsI thought these two charmers were difficultto establish in cultivation eventhough D. cucullaria is locally abundantin certain natural settings. These seemedalmost invariably to be at the baseof rocky slopes in woodlands, mostalways where the rock was acidic.Investigation showed that the tuberslie close to the surface in pockets ofalmost pure humus.Efforts to move a few clumps ofDutchman's Breeches from an areaalong a major highway where expansionof the road was impinging onthe rocky slope, were successful to theextent that some leaves appeared thefollowing year, but no blossoms. Mysite, though rocky and shaded by hightrees was amidst rocks of StockbridgeMarble, an ancient metamorphosedlimestone. Meanwhile I had purchased106

from a "wildflower nursery" — thatmeans usually plants collected in thewild — some tubers of Squirrel Corn.These I put in a nearby spot undersome Kaempferi Azaleas. For a yearor two there were a few sprigs ofdicentra foliage and no real displayof blossoms, so I tried moving a fewcorms of each species up into theacid soil of the woodland garden.Then, I think it was the third year,there was a fine burst of early Dutchman'sBreeches blooms along the pathamidst the limestone rocks. And yearby year their numbers increase andthey have spread into the most unlikelyand enticing pockets: amidst ferns,primulas, mertensias, arisaemas, allhuddled together with the Dutchman'sBreeches generally leading the paradeof flowers. They appear to thrive oncompetition and, conversely, never interferewith the most delicate neighbors.After about five years I suddenlybecame aware that at the very endof the blooming season for the Dutchman'sBreeches, there was a greatflush of flowers on an expanding bedof Squirrel Corn which had been quietlymultiplying unnoticed beneath theKaempferi Azaleas.What I begin to think is that youneed patience and fresh seed. Thecluster of tubers usually breaks up inthe transplanting and the individualgrain-like scales become scattered, takinga few years to grow into a clumpsufficiently big to support blossomingstems. The shining black seed has, atits point of attachment, a fleshy whitearil, which shrivels quickly when exposedto air and it would seem that oncethis aril becomes desiccated the seedloses viability.Both species are beginning to appearhere and there in greater and greaterabundance in other areas of the garden,either among basic or acidic rocks.Seeds do get scattered and it is quitepossible that the tubers also are spreadabout by foraging mice. Some finda good niche. And the rewards in thevery early spring when the butterflyblossoms dance in the chill air abovethe lacy foliage are heartlifting.A DICENTRA VARIANTMERCER REEVES HUBBARDPittsboro, <strong>North</strong> CarolinaOn a walk in central <strong>North</strong> Carolina'sChatham County woods with my husbandand his father some years ago,we came upon an exciting concentrationof native plants in flower: Alum Root,Foam Flower, oxalis, Jack-in-the-Pulpit,Hound's Tongue, Trout Lily, whitehepatica, flags, Dutchman's Breeches,Toothwort, Paw-paw, and Buttonbush,all could be seen within an area ofa few acres. I never have found mygood walking stick that I threw downto look more closely at a large populationof dicentra. One group was easilyrecognized as the typical white Dutchman'sBreeches, Dicentra cucullaria,but there were others — pink ones,really pink ones!Not finding a pink D. cucullarialisted in our books, we crept up uponthese plants several times during thenext few years, wondering if they were107

eally pink breeches or if the whitehad faded into pink. Color remainedconstant; in addition the pinkblossomedplants seemed to present aslightly different aspect from the rememberedDutchman's Breeches of ourmountains.Hoping that we had discovered anew plant, finally I found my wayto native plant authority, Dr. AlbertE. Radford, in his office on the topfloor of the Botany Building at theUniversity of <strong>North</strong> Carolina at ChapelHill, a hike quite as exhilerating asclimbing the steep bluffs of Chatham.Dr. Radford said that what struckhim at first was the color and shapeof the corolla. He said that he hadnever seen that variation: the smallcorolla, the more rounded apex, thebeautiful pink coloration. "You get alittle pink in Dutchman's Breeches, butnot all that pink — a rich pink whichwas retained." He added whimsicallythat the breeches were not as baggyas those regularly seen in D. cucullariaand promised to look it up to seeif it could be a new variety.In Brittonia, at that time a publicationof the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Society</strong> of PlantEnvironments edited by Kingsley Stern,Dr. Radford found that Dicentracucullaria is listed as having a greatamount of variation, particularly inrespect to flower form. The shape ofour variant, as well as other shapes,was sketched and treated as a varietyof D. cucullaria, but with no recognitionof named varieties. I thought I wouldsurely get famous and have 'Mercer'sPink Breeches' officially listed; this iswhat volunteers at the <strong>North</strong> CarolinaBotanical <strong>Garden</strong> named the variant.Dr. Radford said we'd watch it fora while and see what happens. "I don'tthink its going to change color orshape; I think it's genetic. A disjunctpopulation which is genetically differentis likely fixed and might evenbe a new variety."Of significance, possibly, is adiscovery made last spring, while theplants were being photographed by KenMoore, NCBG Superintendent. A formwas noticed with very straight corollasacs (breeches) with dark reddishbrownand others with orange coloringat the constrictions of the petals. Afterviewing the slides exhibiting the variousforms of straight corolla sacs, roundedcorolla sacs, and varying shades ofpink, Dr. Radford expressed enthusiasmover the distinct genetic variation withinthis population. The entire populationmerits further observation andstudy and horticultural selection ofsome of the specific forms.After the hard winter of 1978 theseplants struggled to bloom according totheir accustomed schedule. Although thewinter was below freezing later thanusual, the plants came up and werein bloom within six days. They couldalmost be seen growing.This gets more interesting all thetime. We don't know how many newplants are left to be found, but we'llbe taking more walks in the woods.<strong>1979</strong> Seed List CorrectionPlease note that Number 55 should read Aciphylla montana Armstrong,the name under which it was contributed, and not A. lyallii,the result of unauthorised alteration.James R. Le Comte, Donor 481108

WE'RE IN THE CHIPS:Exploring the Himalayas of KashmirBOYD C. KLINE, Medford, Oregonwith EDWARD HUGGINSPhotographs by Mr. KlineThis last July we flew from NewDelhi to Srinagar, in northwestKashmir, and there set out upon theadventure of a lifetime.There was Barry Starling of GreatBritain, the ericaceae expert and accomplishednurseryman, with his patience,persistence, and quiet Britishhumor — and Reuben Hatch of Vancouver,Washington, the hard working,successful rhododendron nurserymanand leader of our expedition, his visitto Kashmir four years ago now servingus well indeed — and, of course, yourstruly, the old man of the mountains.Making headquarters at once inSrinagar, the capitol of Kashmir, welooked forward to a month of excursions.We would drive northeast intothe Ladakh territory and perhapsglimpse to the far north the snowypeaks of the Karakorum Range. Intrepidexplorers of wilderness areas,we three would scramble up countlessmeadows and screes through easternKashmir, even as far south as Menali,everywhere searching along the highestridges to behold all the fascinatingplants we had read about for yearsbut never seen. Challenging theHimalayas has a rather romantic ringto it. But when I actually gazed upat those awesome heights I could onlymurmur, "Egad, what have I gottenmyself into?"Such was our reaction one morningin Sonamarg, a tiny village nearLadakh and some eighty-five milesnortheast of Srinagar. It was July 30,1978, the weather perfect.We rose at seven-thirty and wentto the village "pony-boy" station. Ghul,our forty-five year old "boy," saddledour ponies and we mounted, jiggledour stirrups, and were off — precededby Ghul and his pack-ponies laden withour paraphernalia as well as with tents,food, and supplies for our grand entourage— four pony-boys, a cook,a guide, and the guide's twelve yearold boy. So began the trip that wouldtake us twenty miles northwest to LakeKrishensar, to Lake Vishensar aboveit, and up at last to the 13,000 footridgeline. In these four days we wouldsee the best plants that we found inall Kashmir.The trail out of Sonamarg headeddown at first. It then climbed mileafter mile until, after a 2,000 foot ascent,we reached a ridgeline meadow.Ahead, northwestward, the meadowsloped up sharply to a soaring peak,its spire a gray, shaly rock in nearlyvertical, tilted layers, its side a greenmantle swooping to our left to formthe meadow's spine before plunging.Sheep herders' mud huts clustered nearthe spine. Peak after peak marchednorthward, each with its up-slope peltof dark trees and lighter green shrubsfingering toward but never surmountingthe naked spire, and each with itsdownslope striations of gray rock and109

scree. Close to our right, a forest oflong-needled Himalayan pines and Indianfirs edged the ridgeline, whichfell north to a river valley.Barry, Reuben, and I wanted to exploredown this north-face trail. Itsslippery mud terrified the poniesthough, so we dismounted, leaving Ghuland his boys to lead our mounts fartherup the ridge to a rock and scree descent.We three made our way toward thevalley.Alongside the upper, forested partof the trail, in shady places amongthe rocks we found a wide variety offerns — athyrium, polystichum, asplenium— all in species unknown tous. Barry gathered fronds with plentyof ripe spore, and I could not resistpicking out several small specimens.The trail opened out into meadows.We waded down through acres offlowers waving at us in the wind, thesalvia and geranium and potentilla soabundant that we soon walked amongthem as familiarly as among oldfriends. And even when this or thatrare little beauty peeped out, no matterhow new and exotic, no matter howshe widened our eyes, Barry wouldhardly betray the twinkle in his eyesas he bent down to observe quitecalmly, "This looks good." BeautifulMeconopsis aculeata grew in singleshere and there, the flower's baby bluepetals flared out around a golden ring.We saw both white and yellow formsof Anemone obtusiloba, some closetogether. The fern-like foliage of Adonischrysocyathus appeared in great clumpsten to fifteen inches high among therocks, each stem topped with a large,solitary, golden yellow bloom. We cameupon a Salvia hians more than a foottall; the cluster of large, basal foliagegrew in moist soil, where rivulets ofmelting snow may once have carved abed, and the dark blue flowers werehuge. Instead of the usual purple, theyhad throats of white.Farther down the slope, in a jumbleof rocks, we were examining cheilantheswhen we heard a clatter and lookedto see our ponies scrabbling, pitching,and jouncing goatlike over the mazeof boulders, manes abobbing. We shookour heads and laughed, glad to beafoot.PrimulareptansThe trail dropped precipitously tothe river and brought us to a ridgewith layers of flatrock shale. "Weshould find Primula reptans in here,"said Reuben. And sure enough, we did.Gorgeous things! Their difficulty in thegarden paled before their rare beautyhere in the valley. Tight, flat matsthey were, their tiny buns pressed rightagainst the outcropping's shaded face.With the patterned stone a fascinatingbackdrop, the extremely compressedbuns and diminutive leaflets were strikingenough. But the blooms in fullflower clinging tightly to the mats —the sight raised the hair on our necks.In dark purples and light lavenders,the blossoms huddled upon the foliageas though trying to hide from ourgaze.110

Shadows lengthened. We had a fifteenmile ride up river to make camp atLake Krishensar, so we mounted up.But our ponies were old hands atfun and games. "Stumble Bum," asI politely named my pony at first,quickly discovered that I froze to thesaddle every time he lurched, so hegleefully tripped over every rock andlog. Then he tried a new game, "accidentally"leaning against a great boulderand squeezing my leg between hisribs and the hard place. Well, the nexttime he tried that I swung my otherleg and "accidentally" gave him a swiftkick to the jaw. Meanwhile, Barry offeredhis pony a marathon lecture onits unsavory ancestry, and on we wentwith never a respite to look at plantsalong the way, teased and tested atevery river crossing, hill, and pebble.Before nightfall we reached Krishensar(11,500 feet), a large lake atthe base of the mountain we wouldclimb the next day. A young Germancouple, camped near the water, spokehappily about the fishing in the river,where they had caught fine Germanbrown trout. We made camp on a flata few hundred feet below the lake,near where the river emerged. Ourguide went fishing. Barry went looking— and in rock crevices right by ourcamp found Asplenium viride, adelightful, tiny fern with the stems notblack but green. He discovered Aspleniumseptentrionale on a large, solitaryrock in a meadow nearby, the veryfern I had seen in the Colorado <strong>Rock</strong>iesthe year before.At six the next morning we tooka quick breakfast, left everyone behindbut Ghul, and went for the gold ring.Right away, on the steep, open meadowthat mounded up from Krishensar tonearby Vishensar, we spied the huge,bright yellow flowers of foot-high Geumelatum as well as the most strikingof all potentillas, P. nepalensis, its oneto two foot stems procumbent and tippedwith beautiful crimson blossoms,some variegated to an orange-red. Thenup and up the ponies struggled, noshenanigans today, and at more than13,000 feet we reached the top saddleof the ridge above Lake Vishensar.From the steep climb and the altitude,Ghul had a terrible headache, so Igave him some aspirin and told himto rest before he headed back downto camp with our ponies. Barry, Reuben,and I wished to spend the dayon foot exploring the chips.Along the whole ridge a mantle ofchippings overlay a deep, rough scree.These finely shattered chips had brokendown from the many shaly outcroppingspoking up from the ridges. All of thesehigher outcroppings looked likebrownstone.Right at our feet we noticed padafter pad of Androsace sempervivoidesand A. muscoides. The dark, heavilyflowered mound of Androsace mucronifoliasurprised us with its tinyrosettes.Soon we came upon the Queen ofthe Himalayas, Paraquilegia grandiflora.Right up on the windsweptridge, it grew tightly adpressed to thesurface of chippings and stood barelyone inch high. Most of the seedpodswere green, but we scurried from plantto plant and finally, with diligence,collected a fair supply of ripe ones.Looking at the unexpected abundanceof plants here, we felt overwhelmedto think of all the seed that wouldripen in just two more weeks. Then,knowing that every time we found thisshaly, sandy-red rock we would findP. grandiflora, we explored the northface of a great outcropping anddiscovered several dozen plants (withtremendous taproots) all up and downthe labyrinthine stairsteps of rock. On111

some plants the aquilegia-like foliagecurled into tight little fists as thoughParaquilegiagrandifloraprotecting its wealth of blossoms andseed; on others the leaves lay open, contouringthe whole plant into a magnificentmound. We found amazing variationnot only in the foliage but in theflower — one with blooms the size of aclime, another smothered with blossomsthe size of a quarter, and still others aslarge as a half dollar, twice the size ofany other forms I had seen. In contrastto the well-known but smaller, bright lavenderflowers found in Nepal and elsewhere,these had a light lavender tintupon the back of the petal, as we saw onone plant with its dozens of buds stilltight — but the whole inside of the openbloom was pure white, a lovely Queen.Higher up the ridge we climbed, seekingMertensia tibetica. Here a deepred allium bloomed in large groups,yet onions hardly drew our interestamidst the teeming royalty. For in thisarea we came upon pink-blooming patchesof Androsace muscoides, Corydalisthyrsiflora with short, compact flowerheads of deep yellow, and the huge,flat, succulent leaves of Corydaliscrassifolia, which despite its rather dulllavender flowers aroused interest withits inflated seedpods. The WhiplashSaxifrage, S. flagellaris, waseverywhere, one of the very few plantsnot endemic to Kashmir (how curiousthat it grows at 13,000 feet both hereand in the <strong>Rock</strong>ies). The large yellowblossoms whipped and danced in thebreeze, while below them the reddish,spidery stolons crept out along theground for new screes to conquer.Another very interesting saxifrage, butnew to me, was S. jacquemontana,its bun not only molding itself to rockyledges but its yellow blooms a deeporange-yellow. The flowers seemedunable to open themselves fully. Onrock outcroppings we saw S. imbricata,the tiny leaves compacted into a tightbun; from the center of the leaf clusterscame small, stemless, single whiteflowers. And we found S. sibirica, theCorydalisthyrsifloradense tufts of reniform leaves one inchacross and the stems four to eight inchestall with bulbils at the base; acorymb of fairly large white flowerstopped each stem. To our delight, S.sibirica grew thickly amidst the beautywe came seeking — Mertensia tibetica.We found it all around, an amazingmultitude, some clustering under rock112

ledges, others taking full sun right outin the open. Unlike most mertensias,the dark blue flowers turned their facesupward, as if sipping the infinite azureof Kashmir.Mertensia tibeticaBarry glanced up — "We seem tohave a visitor." Not far above, onthe top ridge, a sheep herder staredat us — peculiar white men scamperingabout and grabbing plants and seedand clambering straight up the mountainside.One large wall of gray, creviced rockcontained some beautiful Himalayan endemicsthat held us spellbound. In therock shelving we saw Primula reptans,Primula elliptica, Mertensia tibetica,and Androsace sempervivoides. On astone ledge above us stood a Sedumcrassipes with its clusters of twelve inchstems arising from a single root-stock,each stem topped with bright red, paintbrushflower heads. And there, rightbeside it on an eight inch stem, thehoodlike yellow daisy of Cremanthodiumdecaisnei peered at us.We reached the shepherd's level. Wesaid nothing. He said nothing. We walkedon, just a mite self-conscious.Clouds, like the sighs of a mountaingod, ambled about the gray peaks, touchedthem lingeringly, and moved on.Another ridge and another, and theday wore on. The mind can only absorbso much. Ever intoxicated withblossoms, Gentiana argentea roamed far"^^iS8S8^^M'^'i'•'Barry Starling and Reuben Hatch on Vishensar Ridge113

and wide over trie high meadows;though a small annual only three incheshigh, it was dense with terminal clustersof bright blue flowers. Pedicularisshowed a grand array of sizes and colors— the variegated white and rose-purpleof P. pectinata, the bright rose-purpleof P. siphonantha, the one and a halfinch long pale yellow blooms of P.versicolor. Soon, excitment settleddown. We squirmed around to get theright photo angles. Talk grew quieter.A Pedicularis bicornuta, one foot ofpure elegance just ballooning with largepuffed yellow blossoms like giant butteredhominy, drew a speculative look,a whispered "Nice," and a couple ofphotographs.Along the bowl-rim ridges we circledback and down to camp. Tired. Contented.The next morning, August 1st, webreakfasted on trout our guide hadcaught and took it rather easy by hikingup a small canyon between Krishensarand Vishensar. Here we spotted aRhododendron anthopogon and a fewspecies of primula. We gathered seedpodsfrom Aquilegia nivalis. Above all,we came upon a dwarf Aconitumheterophyllum only ten inches high, butwith unusally large helmet flowers oflime green, striped a dull, purplishbrown. Then Barry found his longsought Cassiope fastigiata at the topof the canyon ridge.We got back to camp by midafternoon,itching for a swim, and traipsedup to the shore of glacier-fed Krishensar,Canadian Club in hand. Ah, a fewswigs to warm up. Then we stripped,ran, and dove into the lake — hah!— and out much faster. Towels. Clothes.A few more swigs and lots moreplant talk occupied a beautiful, beautifulafternoon.We spent that evening caring forthe day's collection — picking out deadleaves and debris, washing roots clean,enclosing each plant in a plastic bagto retain moisture, and packing themtogether snugly in cartons. And thenext morning we prepared for the journeyback to Sonamarg.Only when Ghul yelled "Osha!" atespecially steep, precarious spots didthe ponies leave off their fun and gamesand attend to boulders. Plantsmen arenever content in the saddle, though,so on and off we got to check plantsalong the return trail. A monsoon rainswept upon us, soaking us to the skinin seconds, and for a quarter of anhour we had the ride of a lifetimeon slippery saddles upon bouncing poniesup mountain trails and down. Inthe terribly rocky, muddy area beyondNichinai Pass, Reuben's pony flounderedto its belly and pitched him headover heels into muck. Reuben calmlyremounted. All the while I kept givingmy pony swift kicks for his trippingtricks and his propensity for choosingwrong trails and so, when we got backto Sonamarg and I got one foot onthe ground but the other boot stuckin the stirrup, the pony, expecting welldeserved kicks in the ribs, kept sidesteppingand sidestepping and I kept hoppingalongside like a one-legged duckwishing I could kick that varmint. Ghulfinally got my boot out and I spitout a few purple epithets. Ghul onlygrinned and shrugged.I joined Reuben and Barry, who weregazing back at our mountain peaks.Had we actually conquered a weebit of the Himalayas? Had we perhapsput our footsteps beside those of Blatter,Coventry, and other great plant huntersof the past? At least in our heartsand minds we had our own small "Valeof Kashmir," twenty miles long, amillion memories wide.Everything we had come seeking wehad found, except Corydalis114

cashmeriana. We had hoped so muchto find that, and perhaps it was inanother area (Zojila Ridge, no doubt),or possibly mere steps from where wehad walked. In fact, it may even havepassed from bloom and gone to seedright under our feet. But the plantsthat we did find exceeded our hopes— Metensia tibetica in unbelievableabundance, the outstanding beautifulPrimula replans, and thousands uponthousands of Paraquilegia grandiflorain all her loveliness.Now, having been home for severalweeks, an interlude affording me occasionfor deep thought, in retrospectI must confess with all honesty —•I wish I had kicked that damned pony!A SMALL GLAMOROUS SHRUB:Fothergilla gardeniiMRS. RALPH CANNONChicago, DlinoisFlowering shrubs are among the mostimportant features of a garden; theydefinitely play a supporting role. If thegarden is small the lack of space preventsthe gardener from growing anythingapproaching the collection of hisdreams. The temptation to plant moreand more shrubs leads to overgrowthalong with drastic pruning which resultsin the shrubs losing their natural shapeand beauty.There are many dwarf species andvarieties that should be considered forthey not only contribute flowers butbeauty of form and foliage. A dwarfshrub worthy of inclusion in any collectionis Fothergilla gardenii (F. alnijolia)which rarely exceeds three feet inheight and is very striking both inspring and autumn. Belonging to theHamamelidaceae family makes it ahandsome cousin of the Witch-Hazel. Itdoes well in semi-shade and on a lightacid humus soil. This little roundupright bush prevails with its foliageand flowers against any competitionfrom any flowers. Being low growing itcan be ideal in many different positions,rock gardens or general landscapedesign. One of its virtues is that itflowers at a very tender age so there isno wait for a certain size to be reachedbefore you can expect flowers.Its witch-hazel like leaves are obovateto oblong, base rounded or broadly cuneate,to two inches long and coarselytoothed; nice green color above andpaler beneath. In May it produces fluffyinflorescences of fragrant flowers resemblingstubby bottle brushes. Thequantity of bloom makes the shruboutstanding. These white blossomswithout petals are borne in dense terminalheads in which the stamens arethe conspicuous part. They appear inshort clusters on the naked branchesbefore the unfurling of the leaves andare most decorative. There is a particularcharm about shrubs that flowerbefore the tufts of green leaves show asit permits the structure of the nakedtwigs that support the lovely whiteflowers to be seen.Fothergilla gardenii was named afterthe Quaker, Dr. John Fothergill. In1762 Dr. Fothergill had a most notablegarden in Upton, England, second onlyto Kew. After eighteen years his gardenscontained 3400 species of exoticplants in addition to his trees and115

shrubs. In 1772 the nurseryman, JamesLee, made the following request in a letterto Linnaeus, "I know Mr. Miller sentyou a drawing of a plant he wanted youto name after my great friend Dr. JohnFothergill. The doctor is fond of thatplant as it is sweet and elegant and willendure in the open air in the severest ofwinters." Fothergilla gardenii answersto the description of this plant. The gardeniipart of the name is in honor ofanother contemporary doctor, Dr. Alexander<strong>Garden</strong>, who practiced inCharleston in 1755 but spent all thetime he could spare from his professionon botany. He corresponded frequentlywith Linnaeus.We are told that this shrub is hardyinto Ohio and Massachusetts although itis a native of the south-eastern statesand mostly from the Appalachianmountains. It can be propagated fromstem cuttings, root cuttings, by layering,or from seed. Good plants can be obtainedfrom most garden centers andplanted in the spring at least by the firstof May.Frequently when seeking plants withdecorative shades of colored autumnleaves one turns to some member of theWitch-Hazel Family. Few bushes canrival Fothergilla gardenii for theorange-yellow color of its leaves beforethey fall in the autumn. This seasonaleffect is very glamorous. One thing iscertain, even one specimen of this littleshrub can be worthwhile and will bringcolor and elegance to your garden.Lester RowntreeLester Rowntree, a recipient of the ARGS Award of Merit in 1967, died on March21, <strong>1979</strong> just eight days after her 100th birthday. Born in England, she came to theUnited States with her parents when still a school girl and spent most of her adultlife in California where she had an astonishing garden built on a steep mountainsideoverlooking the Pacific in Carmel Highlands.Mrs. Rowntree spent comparatively little time in her garden, however, as shetraveled extensively, usually alone, throughout the southwest United States andMexico, even exploring as far afield as the Mediterranean maquis and the Chileanhighlands to collect the seed of native flora of these areas, which she then dispensedthroughout this country and abroad.Mrs. Rowntree's two books (unfortunately now out of print), Hardy Californiansand Flowering Shrubs of California, are a delight to read. A writer of talent, herbooks, though authoritative, are not dry botanical texts, including, as they do, livelyaccounts of her adventurous explorations.Mrs. Rowntree maintained joint citizenship in Britain and the United States andon the occasion of her hundredth birthday received a cable of congratulations fromQueen Elizabeth II. She was a charming person with a lively sense of humor, adedicated plantsman and conservationist, and a legend in her own time.116

NOMOCHARIS IN MASSACHUSETTSRONALD A. BECKWITHSouthampton, MassachusettsPhotographs by the author"If the Peat <strong>Garden</strong> enthusiast had to confine himself to twelve genera, Nomochadswould not be last on that short list." — Alfred Evans, The Peat <strong>Garden</strong>In 1889, in the "Journal de Botanie,"Adrien Rene Franchet, Director of theMuseum D'Histoire Naturelle in Paris,France, designated the genusNomocharis from specimens collectedby Delavay in western China. The namederives from the Greek nomo formeadow or pasture and charts, meaningoutward grace, loveliness. Surely adelightful name for a delightful plant.Our friends the taxonomists made nomistake with that name.Franchet apparently set up the genuson account of the basaily swollen filaments,and the wide open flowers withthe outer segments entire whilst theinner segments are much broader andfringed at the margin, with large, almostlobed nectary glands.Following the introduction of newspecies, the genus was reviewed inseveral papers. The first revision waspublished in 1918 by Sir Isaac BayleyBalfour in the "Transactions of theBotanical <strong>Society</strong> of Edinburgh" andwas followed by E. E. Wilson in 1925in Lilies of Eastern Asia; W. E. Evansin 1925 and 1926 in "Notes," EdinburghRoyal Botanical <strong>Garden</strong>; andD. Wilkie in 1946 in the Royal Horticultural<strong>Society</strong> "Lily Year Book."Fourteen species were recognized,some of which possessed slender filaments.A more recent revision donein 1950 by J. Robert Sealy in the"Kew <strong>Bulletin</strong>" reduced the genus toeight species, placing N. euxanthum,georgei, . henrici, lophophorum,mackliniae, nanum, oxypetalum, andsouliei in Lilium. Nomocharis, as conceivedby Sealy, is a small homogeneousgenus, obviously closely allied toLilium, Fritillaria and Notholirion. Thisrelationship has given rise to plantsthat loosely fit into either genera,therefore, periodically there are shiftsin taxonomic opinion and species popback and forth between the genera.To complicate matters further,Nomocharis species have proved to bea trifle promiscuous, presenting us withthe problem of natural and man inducedhybrids. This has resulted in the creationof the grex N. x jinlayorum.The eight species that Sealy acceptsare as follows: N. pardanthina, meleagris,mairei, basilissa, farreri, synpatica,aperta and saluenensis. Of these, N.basilissa and synpatica are probably notin cultivation. In this articla, I will confinemyself to the Nomocharis that Igrow and which I believe to be readilyavailable in the seed exchanges.The history of the introduction ofNomocharis into cultivation resoundswith the names that reverberatethroughout the world of rock gardening:Forrest, Fairer, <strong>Rock</strong>, Ward, andnot forgetting those great French missionarycollectors from western China,Delavay, Soulie and Maire. I think thatperhaps here we should acknowledgethe tremendous part that the Royal Botanic<strong>Garden</strong>, Edinburgh has played117

in the history of the genus N omocharisand its consequent retention in cultivation.I am sure that I speak forall growers of these wonderful plantswho firmly believe that, if all else fails,Edinburgh and that select group ofastounding Scottish growers can becounted on to keep things going. Taxonomically,Edinburgh has been in theforefront, with many reviews andpapers on the genus emanating fromthere.Pere Jean Marie Delavay (1834-1895) was a priest in the French MissionsEtrangeres and from 1867 untilhis death in 1895 lived in China. Hewas stationed in northwestern Yunnanbetween Tali-fu and Lichaing. Workingmostly alone, he sent a most remarkableamount of material back to France,to the extent that some fifty years afterhis death his herbaria were still beingsorted and classified. It was to Franchetat the Paris Museum that Delavay sentthe first known collection o fN omocharis. This was classified as N.pardanthina. Delavay collected N. pardanthinain June 1883 in the pasturesof Mount Koua-la-po in the Tali district,Yunnan Province. However, it is toGeorge Forrest that we are indebtedfor its introduction into cultivation. Itfirst flowered at the Royal Botanic <strong>Garden</strong>,Edinburgh in 1914 from seed thathe had sent back. Frank Kingdon Wardalso collected and sent back seed. N.pardanthina ranges in height from eighteento thirty-six inches with whorledfoliage. The flowers tend to be nodding,about three inches across, white or flushedwith the palest pink, the innersegments fringed whilst the outer areentire. The face is quite heavily spottedcrimson towards the center, giving theeffect of an eye. The filaments areswollen from their base to a little overhalf way up, after which they becomerapidly reduced, becoming thread-likebefore attaching to the anther. Thisswelling is quite unlike anything inLilium.N omocharis farreri is sometimes givenas a variety of N. pardanthina,which it quite closely resembles.However, N. farreri is reputed to growmuch more strongly, to have narrowerleaves, and the inner segments of theflower are not so heavily fringed, beingonly nicked. Plants that I have grownfrom seed under this name did notshow these characteristics. N. farreriwas first found by Farrer in the HpimauPass. Upper Burma in 1919 (Burma-YunnanBorder Region). It waslater collected by Forrest and by Ward.NemocharisapertaNomocharis aperta is another Forrestintroduction. He collected N. apertasometime in 1906 in southwesternSzechuan and northwestern Yunnan.This is rather a distinct plant withthe segments entire and the perianthof a flat saucer shape. The more orless outward facing flowers are threeto four inches across, white or flushedrose with blotches of deep crimsonaround the nectaries. The filaments arenot swollen. Although this species isreported to attain thirty inches, withme it tends to be rather short, growingsome eighteen to twenty-four inches tall.118

The leaves are paired to scattered(unlike N. pardanthina).Nomocharis mairei (how I admirethis plant) was first collected by E.E. Maire in 1912 in pastures at 10,000feet at Ta-Hai in northeast Yunnan.However, again we are indebted to Forrest,and later Ward, for its introductioninto cultivation. I find it difficultto categorize plants, but this really isa most lovely plant, rather reminiscentof an Odontoglossum. The tepals arewhite or flushed pink and heavily spottedwith crimson over all the segments,giving way to a crimson-eyed center,the inner tepals are beautifully fringed.By contrast, the pollen is yellow. N.mairei var. Candida is reported in theliterature. It is said to be pure whiteand unspotted. The flowers of N. maireihold themselves well, facing out orslightly down, the tips recurved. Thefilaments are club shaped, but again,they become thread-like before attachingto the anther. The leaves arewhorled.When I was preparing to write thisarticle, I read the published speciesdescriptions and I found that some ofthem did not exactly correspond withmy plants. Comparison of livingmaterial with the herbarium sheets atthe Gray Herbarium of HarvardUniversity was made as a further check.In this I was much aided by Mr. H.Ahles, Keeper of the Herbarium at theUniversity of Massachusetts-Amherst.Although Nomocharis aperta and N.mairei matched well, the conclusion wasreached that there were no true N.pardanthina or N. farreri amongst myplantings even though several batcheshad been raised from seed under thosenames. Many came very close, but didnot quite fit the descriptions. Referencesto the Royal Horticultural <strong>Society</strong>'s LilyYear Books led us to the conclusion,somewhat to my dissatisfaction, thatNemocharis maireiI had a fine batch of the grexNomocharis x finlajorum.Perhaps a review of how this namecame about would be fitting. Duringa visit in June 1969 to the gardenof Keillour, the home of the late Majorand Mrs. Knox Finlay, Patrick M.Synge, former Editor of the Royal Horticultural<strong>Society</strong>, saw several groupsof Nomocharis which he believed tobe of hybrid origin. It was thoughtunlikely that these plants would be cloned,but would be kept in cultivationby seed propagation, and therefore, itwas decided to give them a grex name,hence N. x finlayorum, after MajorKnox Finlay, who for many years was aregular exhibitor and superb grower ofNemocharis x finlavorum119

these plants. The original descriptioncan be found in the Royal Horticultural<strong>Society</strong> "Lily Year Book" 1969, p. 107.What can I say about A. xfinlayorum to help you identify them?Mostly, they have whorled foliage andthey have an obvious affinity to A.pardanthina, farreri and mairei. Theflowers are white to pale pink, thespotting anything from all over theface to confined merely around the centraleye. Indeed, some have no spottingbut just the central eye. They are verylovely and worthwhile additions to anygarden; a clump standing some twoto three feet tali is a most delightfulsight.Another Nomocharis that I am raisingfrom seed is A. saluenensis, whichis reported to be closely aiiied to A.aperta. Aomockaris saluenensis was collectedfrom altitudes between 9,000 and14,000 feet in southeastern Tibet,northwestern Yunnan, western Szechuanand northeastern Burma. The presentstock in cultivation is believed to bederived from George Forrest's collectionsof 1921-1922. Photographs andattendant literature show that the widelysaucer-shaped flowers are upward facing,white to pale pink (even paleyellow has been reportedJ with purplishspotting towards the center. These areborne on plants that grow two to threefeet tall. As in A. aperta, the filamentsare not swollen and the leaves arepaired to scattered. Its name is derivedfrom the Salween River. I would ventureto suggest that the photographof A. saluenensis featured in The Peat<strong>Garden</strong> by A. Evans (Plate Xd) isa good example of this Nomocharis.But "Ah" you say, "This is all verywell; how do we grow them?" I canonly speak from my experience of themhere in the <strong>North</strong>east. I tried growingthem in Britain (just north of Londonon the East Coast) when I lived there,but 1 never got them to flowering size.While I have been here in the UnitedStates (Massachusetts), 1 have hadmuch better success. Starting off withseed in 1972, I have tried various seedmixtures, but these seem to make littledifference; drainage seems to be theimportant criterion. The mixture that1 use now is basically: one part ofpeat humus, one of loam and one ofsharp, course sand to which a basefertilizer is added. Then according tohow the soil mix "feels," (and you,as rock gardeners, are just as familiarwith the term as I am) I add gritor one-quarter inch trap rock screenings,I suppose perlite would be allright too. Keally, the drainage is themost critical factor. I do not use JiffyMix or vermiculite on slow-germinatingseeds. I do not have anything againsteither; it is just that during the lengthof time that I leave nomocharisseedlings in the pot, Jiffy Mix andvermiculite tend to break down andget mushy.1 have used baby flats as containersin the past, but 1 now prefer fouror four and a half inch square plasticpots as they are deeper. 1 always puta layer of three-eighths inch trap rockover the bottom for drainage and thenfill with the medium to about one-fourthinch below the lower rim. The mediumis then firmed.I try to sow the seeds very thinlyas I am going to leave them in thepot two to three years, depending ontheir growth. One can usually delermineif the seeds are good by placing themon wax paper or thin typing paperand holding it over light. You shouldbe able to identify a good seed becausethe embryo appears as two lines inthe endosperm, going part of the wayacross it. However, use this as a rough120

guide and do not discard any seeds,only what is obviously chaff, eventhough only a few appear good. I alwaysshoot for the works and assumethat I might have missed some. If theseeds appear really good, I will sowmaybe twelve in a four and a halfinch pot, but if it looks very poorand I can see only a few seeds withthe embryos plainly visible, I will sowsufficiently thickly that they are perhapseven touching each other. I then coverthe seeds with about one-eighth inchof medium over which I place a layerof siftings from three-eighths inch traprock, i.e., one-fourth inch or less. Justa single layer of trap rock pieces willsuffice. It will help keep the moss out.I then water the seeds in well fromthe top.When to sow? Frankly, I don't thinkthat it matters. The books all say tosow in early spring but I have sownin the fall, and in the winter (January,February). As soon as the seed is sownI put the pots out in the cold framewhere they get frozen solid. In mostcases seedlings will appear in the springalthough I have had them skip a wholeyear and come up the following year.I have also sown seed in April, inwhich case, they sometimes germinatealmost immediately, but sometimes theywait. I want to stress the importanceof not becoming over-anxious and pitchingthem out if they don't germinatequickly; as with all good alpines, waitthree years.For the first year or so after germination,I keep my seedlings in thecold frame, which I shade during thesummer with snow fencing so thatthe pots receive a thin moving shade.I never allow seedlings to flower inthe seed pots, however. Bearing in mindthat they are in smallish pots, I keepa special eye on them during theirsecond to third spring post-germination.Once the plants start putting on somestem growth I plant the whole potfulout as a clump, placing them slightlylower than the soil level and then workingsoil in around the stems to bringit up to soil level. I leave them likethis until the first flowers appear.Usually one or two will flower beforethe others in the third to fourth years.As soon as the flowers are faded,I dig the clump up and separate theplants out. Care must be taken in diggingbecause Nomocharis bulbs tendto get down deep like those of Erythroniums,so you must dig well downto get the spade under them, or youwill leave the bulb behind and causeyourself much annoyance. I like toreplant immediately. 1 separate out thebulbs and I dig holes eighteen inchesacross and nine to twelve inches deepwith the soil at the bottom of thehole well forked over. I then plantsix to nine bulbs in the hole, workingthe soil in around them carefully asI go. Hold the stem and plant themas you would a tree sapling. Take carethat the plants are as deep or evenslightly deeper in the soil than theywere before. They can and will adjustthemselves within reason. I always treadmy plants in after planting, treatingthem more like saplings than bulbs.As to where to plant them? I canonly speak for my garden. I have grownNomocharis in two very different gardens.Though their planting site in bothgardens was well drained, in my formergarden it was much damper than inmy present garden. Also, in the formergarden they were planted on the easternside of Pinus strobus, but the treeswere quite small and dense (twelve toeighteen feet); at present m yNomocharis are growing under a largePinus strobus, mostly on the north andeastern sides, and on a north slope.They have a somewhat thinner shade121

than previously as well as a much driersituation. I think, therefore, that it isreasonable to say that Nomocharis prefersome shade in this climate (westernMassachusetts). I give them bone mealin the fall and I spray them everyten to fourteen days during the growingseason to keep them free of aphids.I think that hand pollination is requiredin order to get seed; withoutit the seed-set is not very good andseed seems to be the only reliable wayto increase Nomocharis. While minegrow well, I have not noticed any greatincrease in numbers. This is merelya general observation, as I do not goround counting them. From all thatI read, they can continue undisturbedfor several years. There appears to beno great need to lift and move themevery three or four years as I wouldadvise with lilies.What does all this mean? Simply,that I believe that Nomocharis can begrown, at least in the <strong>North</strong>east, whengiven reasonable conditions and thatthey are not as difficult as many wouldsuggest. Believe me, they get no bettercare than the rest of my plants. Asalpine growers, you all know the importanceof microclimate and finding theright place for the plant. So far theyhave proved hardy and I have hadno problems with rodents or slugs.This is how I have grown a fewNomocharis. I hope that this will encourageothers to try growing them.I feel there is nothing more satisfyingthan to show your friends a groupof Nomocharis in flower during Juneand July. They have a refined etherealquality about them and they are alltrue alpines with none known in thewild to occur below the 9,000 footlevel. So how about adding a littleGrace to your Pasture?SELECTEDREFERENCESCoats, Alice M. 1970. The Plant Hunters. McGraw-Hill.Cowan, J. M. (Editor). 1952. George Forrest VMH. Journeys and Plant Introductions. RoyalHorticultural <strong>Society</strong>.Cox, E. M. H. 1945. Plant Hunting in China. Old Bourne: London.Evans, Alfred. 1974. The Peat <strong>Garden</strong> and Its Plants. Dent.Wilson, E. H. 1925. Lilies of Eastern Asia. Dulau & Co., Ltd.Woodcock and Stearn, 1950. Lilies of the World. Country Life, Ltd.Royal Botanic <strong>Garden</strong>, Kew. Kew <strong>Bulletin</strong>, 1950.Royal Horticultural <strong>Society</strong>. Lily Year Book, 1932, et al.122The Myth of the Lime-Loving PlantI am not going to say that no plant needs lime and will perish onan acid soil; my experience is far too limited for such a sweepingstatement. I do say that I would not be deterred from trying anyplant I wanted to grow because I read that it must have lime. I amat present growing at least three species which, theoretically, oughtnot to flourish in a pH 5 soil without benefit of lime, namely,Camptosorus rhizophyllus, Clematis — in variety, and Iris unguicularis(seven different cultivars.)"Clematis and lime are forever linked, like salt and pepper," writesgrower-member Richard E. Farrell. How do these myths continue tobe perpetuated?—Pamela J. Harper, Seaford, Virginia

CYCLAMEN IN CONTAINERSBRIAN HALLIWELLKew, EnglandMany cyclamen, including Cyclamenpersicum, described below, require aMediterranean climate; hot dry summers;spring and fall rains; and low,but not prolonged freezing temperaturesin winter. For this reason many ofthe very choice species will not doout-doors in the United States exceptperhaps in the Southwest, though somewill survive in the Southeast if givengood drainage. They can all, however,be grown in pots as explained inthis article by Brian Halliwell of theAlpine and Herbaceous Department atthe Royal Botanic <strong>Garden</strong> in Kew,England. — Ed.The so-called Persian Cyclamen, C.persicum, from which the florist's plantwas developed by selection, did notoriginate from Persia and, in fact, isnot to be found there. It occurs inseveral countries at the eastern endof the Mediterranean: Greece, Rhodes,Cyprus, Israel, Lebanon, and Syria. Inthese countries it can be found fromsea level to a height of about twothousand feet, usually in woodland althoughit also grows in the open amongstshrubs or at the base of rocks. Usuallyit is found growing in alkaline soilthat is well supplied with leaf-mold.Corms, which can be as large as atea plate, may be over a foot belowthe surface where the soil is deep butcan also be just covered where theground is thin or stony. It is veryrare to find corms exposed as theyoften are in cultivation.During the hot dry summers of thesecountries, corms are dormant withgrowth commencing at the onset ofautumnal rains. Leaves appear first inOctober and November with flowersappearing in January or February althoughthey can still be seen as lateas April. Insects are responsible forpollination and when this has occurred,the flower stems elongate; as the seedpod swells, the increased weight bringsit down to ground level. Unlike thoseof the other cyclamen species, the flowerstems of Cyclamen persicum do notcoil into a spring after pollination ofthe bloom. Leaves often die away beforepods are fully ripe. These eventuallysplit to expose sticky seeds that areattractive to ants, who seem mainlyresponsible for distribution.Leaves have serrated edges and areheart-shaped, usually about two inchesacross at their broadest and of similarlength. There is much color variationfrom plain dark green throughout tocompletely silver, but in general thereis a green background on which thereare bands or zones of silver arrangedin attractive patterns.The flowers, which are deliciouslyscented, stand well above the leaveson six to nine inch stems. Petals areabout an inch in length, narrow andtwisted. These are usually held verticallyas in all typical cyclamen. Most oftentheir color is pale pink but a searchin any colony will disclose variationin shades from white to a fairly deeprose and whilst most have a darkereye some are self-colored. Besides variationin color, flowers will be foundwhere petals are held horizontally insteadof vertically, and flowers in which123

there are ten petals instead of five.Few sights are more beautiful in earlyspring than a pine forest in oneof this plant's native countries wherethe forest floor is carpeted with the"Persian Cyclamen". On a warm daythe flower fragrance can be so intensethat it drowns the scent of the pines.Unfortunately such a scene is unlikelyin gardens but an individual plant orplants make a delightful addition toan alpine house or cool room.Cyclamen of all species are raisedfrom seed, most of their forms comingtrue to type. Best results are obtainedfrom fresh seed sown as soon as collectedat which time germination ismost rapid and even; old seed takeslonger and germination is erratic.Unless the gardener or his friends haveplants, fresh seed will be unobtainableso before sowing seed should be soakedfor twenty-four hours in cold water.A compost for sowing can consist ofequal parts of soil, sand, and leaf-mold(leaf-mold seems to suit cyclamen betterthan peat.) Space out the seed in acontainer or sow individually in smallpots, insuring that the seed is coveredwith one-quarter to one-half inch ofthe compost.When fresh seed is not available,sow in January if sufficient heat isavailable (50 to 60° F.) otherwisedelay until temperatures are rising inApril or May. Unless individually sown,pot the seedlings singly into small potswhen they have developed three leaves.Seedlings of C. persicum should be pottedone to a five-inch pot whereas allothers can be potted several to a ninetotwelve-inch pan, insuring that atall times the tubers are kept well abovethe soil. Use the same basic ingredientsas already mentioned but add somelime and a light dressing of balancedfeed.During the summer months, containersare best kept out-of-doors andplunged to their rims in a frame wherethey receive some shade. Waterwhenever required and keep them growinguntil flowering takes place. Timeof flowering will depend on species,when sown, and the amount of winterheat available. Rehouse in the fallbefore frosts arrive. A winter temperatureof 45 to 50° F. is ideal butas long as the glass house can be keptfrost free the plants will prosper. Applywater carefully whenever needed beingcareful that none fall onto the foliageor tubers. Keep the plants in a dryairy atmosphere avoiding at all timesstagnant conditions which encouragedisease.The disease Botrytis is a seriousmenace, attacking first dead or damagedplant material. From here it spreadsto immature flower buds and, whilstthere will be no obvious symptoms,these fail to develop. Pick over theplants at regular intervals, removingyellowing leaves, faded flowers, or anydamaged material taking care whendetaching the stems that no raggedplant remnant remains adhering to thetuber. Dusting the centers of the plantswith sulphur will give control againstthe disease spores and will also actas a deterrent against further infection.When flowering is over graduallyreduce the amount of water but donot dry off completely. As the dangerof frost passes, transfer out-of-doorsand plunge to the rim in a sunnypart of the garden where the plantswill receive such summer rain as fallsso they do not dry out completely. Sunand/or warmth is required by thetubers to insure free flowering in thefollowing season. In wet areas protectin a frame to which maximum ventilationis allowed at all times.Normal watering for C. purpurascens(europeum) will continue throughout124

the summer; for other species it shouldresume as flower bud formation isnoticed or as new leaves start todevelop. Before rehousing, pick overthe plants to remove any debris, scrapethe loose soil from the surface of thecontainer and replace with new. Cyclamengrow and flower best when theyare root bound so repanning will onlybe necessary when the corms becomeso large as to touch each other orthe sides of the pot.THE TURFINGLILIESThere is considerable confusion betweenthe two closely related genera,Liriope and Ophiopogon, the Asiasticturfing lilies; the only differenceseparating them being that the liriopeshave a superior (the perianth attachedbelow the ovary and not to it) ratherthan a half-inferior ovary as in theophiopogons. Ophiopogon comprisesten or more species that range fromIndia through China to Japan andKorea, while Liriope contains fewerspecies, possibly no more than four,which have a narrower range, beingconfined mostly to China and Japan.Both genera form dense tufts of arching,dark green, narrow straplikeleaves from three to eighteen incheslong or more. They bloom in late summerand fall in spike-like racemes thatare usually shorter than the leaves andvary in color from white to deep purple.These and the leaves rise from shortrhizomes, which often produce slenderstolons.Liriope platyphylla (F.T. Wang andTang) and Liriope spicata (Lour) aremuch the same, though the latter seemsto be the one found in most gardens.But here again there is much confusionas the latter plant has been knownas Ophiopogon spicatus var. communis,Liriope graminifolia, L. spicata var.densi flora and L. muscari. It hasflowers of a light purple and thereis a very attractive variasated formwith light green and cream coloredstripes running the length of the leaves.Probably the most exotic of theophiopogons, 0. nigrescens, comes fromnorthwest Nepal. It produces a smalltuft of glossy, dark green leaves aboutfour to five inches tall and flowersresembling those of a creamy Lily-ofthe-Valley.In the best form, knownas "Black Dragon Beard", the leavesare of such a dark green as to bealmost black. The fruit too, a pea sizedberry, is darker than in mostophiopogons, being a deep navy blue.Not all the plants will come true fromseed, however; about fifty percent willhave bright green leaves.Except for some of the ophiopogonsfrom warmer climates, which may needsome winter protection in more northerlygardens, these plants will toleratealmost any reasonable soil or climate.They will do well in most garden soils,but prefer it rather sandy. Though theywill grow in both sun and shade, theyflower best in half shade.Both genera divide easily, are longlived, and make very attractive additionsto the rock garden. Planted closelythey make an excellent ground coverand most forms will spread slowly butsteadily to form a dense mat, a proclivitywhich gives both Liriope andOphiopogon their soubriquet, Lily Turf.John OsborneWestport, Conn.125

A NEW HYBRIDSAPONARTAZDENEK ZVOLANEK AND JAROSLAVPrague, CzechoslovakiaPhotograph by Jan Hulka, PragueKLIMAFor a number of years Czech rockgardeners have been enjoying such saponariahybrids as S. x olivana with itslarge cushions bearing pale rose flowerson a compact mat. It showed its qualityat the May, 1978, Show in Prague,blooming for three weeks in full sun.This hybrid results from the activitySaponaria pumila x ocymoides rubra compactaof good size and the less frequentlyseen S. x 'Bressingham Hybrid' withits smaller, bright red flowers on tinybright green cushions. Now our growersare excited by a new, so far unnamed,hybrid originating in Austria from across between Saponaria pumila x S.ocymoides 'Rubra Compacta.' Thisoutstanding hybrid has flowers of awarm rose up to an inch in diameterof our pen-friend, Fritz Kummert ofMauerbach, Austria. The cross wasmade in 1974 and the seed was sownin October of the same year. Onlytwo seedlings came up. One provedvery similar to Saponaria pumila;the second is the new hybrid.According to Mr. Kummert (and inour experience, also) it is easy to propagatecuttings from plants planted out126

in the garden, but not from pottedplants. Cuttings should be made of theyoung shoots in early June taken fromthe center of the plant when it startsinto growth again after trimming itback following its blooming period.This excellent hybrid has not beenwidely distributed until recently. It hasonly one small defect: it is as yetunnamed.A GOOD TEMPERED SYNTHYRISEDITH DUSEKGraham, WashingtonThe impact of some plants can bestbe described as love at first sight.Others steal slowly into one's awareness,taking on the comfortable companionabilityof a pair of old shoes. Myfirst sighting of Synthyris reniformison the gravel prairies near Olympia,Washington created almost no impactat all. Wee scraps tangled in otherherbage and struggling for the rightto live, they had few leaves and evenfewer flowers. Still, they were theearliest of our native wildflowers. Mostof them were of that indeterminate colorour English friends are wont to callmauve with an almost audible sigh ofresignation. Unlike S. missurica, whoseflowers climb nimbly up the stem, thesewere collected toward the top wherethey did their best to make some sortof showing.A bit of searching revealed here andthere a plant with blossoms of a quiterespectable lavender. More rarely therewould be a pure white one whosevirginity was set off by glowing pinkstamens. "Oh well, might as well tryone," I thought. Prying the chosen oneaway from the stems of the shrub ithad chosen as a provider of shadetook a bit of doing. On arriving home,disengaging the plant from the grassin which it was enmeshed was evena more delicate operation. The resultwas a wisp of roots, four leaves, andtwo scrawny stems of flowers. A checkaround the garden turned up a likelylooking home, rich in humus, wheresunshine and shadow played tag acrossthe plant. Once it was tucked in, Ipromptly forgot all about it as showierplants and other garden matters demandedattention.Early the next spring as I was scootingaround trying to finish the "fall"clean up, a bright spot caught my eye.There was friend Synthyris bloomingits heart out. What a difference! Thescrawny thing had increased to a handsizedclump and was a solid mass ofbloom. To be sure, each flower wasa small thing in itself but when itsocialized with its many fellows, theeffect was quite pleasing. Smallcheckered gray and white butterflieswere as enthralled as I. The plant wasso well attended by them that therewas standing room only. It is saidto be impossible to make a silk pursefrom a sow's ear but this little planthad set out to prove otherwise. Needlessto say, my indifference to this smallperson began to disappear.In succeeding years I have addeda white flowered plant and a few withsomewhat larger petals of a more definitecolor. Each year the original planthas tried to outdo its performance of127

the year before. It would now covera dinner plate with a ruff of purplishold leaves on which sits a perfectnosegay of blossoms. Despite itsfloriferous efforts, it has managed toproduce only a few offspring. Its conducthas been nothing short of impeccable.It neither asks for coddling nordoes it become overly enthusiastic withitself or its kind. Its stature makesit a suitable companion for plants ofthe size of hepatica, bloodroot andcyclamen.Some time later an Oregon pen palinformed me that Sythyris reniformisgrows down that way too only theflowers were blue. Indeed they are,though that is rather an understatement.In contrast to the rather delicate tintsof our local plants, those from Oregonare a rich full blue, sometimes so muchso that they become a deep purple.Plants generally are larger in all partswithout losing the charm of their northerncousins. In addition to this, anddespite being botanically identical, theydo not behave in the same mannerin the garden. Coming as they do fromthe south of Oregon, one might logicallyexpect them to wait for weather hereto moderate before putting on their act.Not so. They think winter is the propertime for blooming and bloom they dofor months on end before our nativesget into the mood. These plants donot flower all at once as ours areprone to do, rather the blossomingstalks flower in succession. I have yetto see one of them produce the nosegayeffect (perhaps in time?) but sincethe individual flowers are of good size,they are still quite effective. They quitemake up in size and rich color whatthey lack in number.As might be expected, in additionto shades of blue, an occasional pinkfloweredplant may be found. Minehas rather small blossoms (for theOregon form) of a very nice pink.It set a nice crop of open pollinatedseed last year. When they ripened, Itucked them in at "mother's" feet.Despite a summer to end all summersfor drought, the seed germinated nicely.Doubtless most or perhaps even all willprove to be blue flowered but withback-crossing something of note mayappear.<strong>Garden</strong> life seems to agree with theOregon plants too for they have increasedin size and vigor without showingany signs of wearing out their welcome.It is not often that one finds a plantof such intrepid good humor.• # »Most dwarf conifers remain constant in character, but occasionallya few branches will revert to type, particularly if the dwarf originatedas a bud sport on a normal tree. A pendulous clone may give rise toupright "leaders," or a side or top shoot with the strong, faster growthof its "normal" parent, will suddenly appear on a dwarf tree. Miniatureivies will sometimes do the same and shrubs grown for their colorvariation may produce branches whose leaves are a normal green.Such reversions should be controlled as soon as noticed by cuttingout the offending branch; if permitted to grow they will destroy thedesired character of the plant.128

VICTORIA ROCK GARDENSSYBIL McCULLOCHVictoria, British ColumbiaPhotographs by the authorVictoria, British Columbia! — I oftenwish I had been aboard the firstship to sail into its harbor, it musthave been lovely in its untouchedbeauty. It still has the setting, hillsand rocky outcrops, encircled insparkling blue water and snow-cappedmountains, but gone are the bogs,streams, and except in isolated areas,the native plants.Even when I was young Erythroniumoreganum grew in multitudes on therocky slopes and in the woods withCamassia quamash and lichlinii,Dodecatheon pulchellum and hendersonii,Sisyrinchium douglasii, and Sedum spathulifolium.Cypripedium calceolusgrew in the Pemberton Woods andCalypso bulbosa carpeted the forestfloor with mauve and filled the airwith its scent. Chimaphila umbellataand Goodyera menziesii (now oblongifolia)were their choice companions. Soyou see the early settlers did not have farto go for choice plants for their gardens.The British Isles were home to manyof these early Victorians so that whenthe great plant explorations to Asiatook place early in this century, newsof the collections came quite rapidlyto Vancouver Island. Indeed, ReginaldFarrer's cousin arrived on the Islandabout the time that Mr. Farrer wasin China and Tibet. The Royal Horticultural<strong>Society</strong> used to send someof the collected seed to Mrs. R. P.Butchart at Benvenuto, now the worldfamous Butchart <strong>Garden</strong>s, to give thema chance of survival if they did notdo well in the United Kingdom.After World War I, many Victorianswere demanding greater variety in theirgardens than the arabis, aubretia,alyssum and campanulas that madesuch a colorful display on the rocksin spring. The Layritz Nurseries alreadywere importing the new rhododendronspecies and exotic trees and shrubs,but Mr. Farrer's books had whettedthe appetite of some keen gardenersand they formed a group in 1922 todiscuss and grow alpine plants. Thisgroup grew into the Vancouver Island<strong>Rock</strong> and Alpine <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong>. Aboutthis time the first rock and alpine nurserywas started by an Englishmannamed Croft Bennet. He published acatalog in 1925, which was quite extensiveand included alpine plants fromEurope and Asia, as well as some hehad collected on Vancouver Island.Other founders of alpine nurseries wereHugh Preece and A. Nichols, John Hutchinsonand Norman Rant. I am toldthat Mr. Preece grew alpine plants toperfection in pans. Mr. and Mrs. Hibberson(of Trillium hibbersonii fame)grew them in troughs. Mrs. Hibbersonnow grows alpines in the alkaline anddry interior of British Columbia at Savonaon the way to Kamloops. I rememberMr. Hibberson speaking of Gentianaverna as though she were hismistress; she grew well for him.In 1929 a young Victoria couple,Mr. and Mrs. Edmund Lohbrunnerdecided to explore the ForbiddenPlateaux on Vancouver Island with afriend. Mr. Lohbrunner had been askedby Croft Bennet to see if he could129

find a white form of Penstemonscouleri. When he arrived in the alpinemeadows, the sight of the myriad numbersof flowers and their exquisitebeauty sealed the fate of Edmund Lohbrunner.He decided to live with them.This was the beginning of what wasto become the famous Lohbrunner Nursery.The beautiful early gardens of Majorand Mrs. A. Morkill, Mrs. B. Wilson,Mr. and Mrs. W. Pemberton, and theMisses Angus have made way for subplants.One area over thirty feet inlength and about five to six feet widebetween rocky outcrops lent itself toexcavation. This was cleaned out toa depth of six feet in places. The areais on a thirty degree slope and faceswest. It has been lined with three inchesof chipped rock for drainage and thenfilled with a scree mixture of one thirdloam, one third sand and one thirdleaf mold with some peat moss and agenerous topping of shale or rockchippings. This scree ends in a moraine,divisions or apartment buildings, butthat of Mr. and Mrs. R. H. Edgellis still beautiful and choice as is thatof Mr. and Mrs. Vern Ahiers. Bothof these gardens have interestingnatural rock formations but each hasbeen developed in a different way.Mr. and Mrs. Ahiers used their rockto provide suitable homes for their extensivecollection of alpine plants byeither building up suitable areas orby deepening crevices to provide a coolroot-run and proper drainage for theirbog and pond.The top of the scree is carpeted byGentiana acaulis and Rhodohypoxisbaurii with Asperula suberosa tryingto hide a magnificent plant of Daphnepetroea. Kalmiopsis leachiana thrivesin the shelter of a north-facing rock.Three Asperulas: nitida, hirta andlilaciflora grow well with Erodiumchrysanthum and Anacyclus depressus.Geum borisii flaunts its orange-scarletbanners with two of the lovelier helichrysums:HH. frigida and milfordiae. And130

these are only a very few of the choiceplants that grow so happily in the scree.Mr. Ahiers tells me that during themany years he has been growing alpinesthat he has had at one time or anotherall but two of the plants mentionedin Royton Heath's book, Collectors Alpines.Quite an achievement.On the north side of the rock outcropcan be found in their due seasonsseveral cassiopes, including C. mertensianaand C. lycopodioidcs; Arctericanana ramps vigorously along with thewee trilliums: T. nivale and T. rivaleand the form known as 'Vern Ahiers.'Penslemon scouleri, Arenaria halearicaand Erigeron mucronata frame a fernycave above a pool whose boggy rimshelters Dodecatheon dentalum, Calthaleptosepala and other bog loving plants.Many shrubs and dwarf conifersenhance the rocky outcrop which isshaded by our native oak, Quercus garryana.Among these grow two convolvulus:C. cneorum and C. mauritanica,cistus, many hebes and Nieremhergiarivularis, one of my favorites.The rock and scree have been meldedinto the lawn very naturally with dwarfrhododendrons and daphnes, includingthe lovely hybrid, D. x 'Leila Haynes.'A well grown plant of Corokia cotoneasteris charming in the spring withits little yellow stars crowning a bedof Lithospermum oleifolium, whose silveryblue flowers enhance the yellowstars.One rocky area is set aside for <strong>North</strong><strong>American</strong> plants: various phlox, includingP. diffusa; Eriogonum douglasii,Penstemon gairdneri, and three of theloveliest lewisias: LL. tweedyi, redivivaand howellii. In spring visitors canadmire a very complete collection oferythronium, trillium and the rareScoliopus hallii. Other woodlandersskirting the rocky outcrops are Shortiauniflora, Schizocodon (now Shortia)soldaneloides, Phlox adsurgens, Gaultheriasinensis, Epigaea repens andseveral cypripedium including an everincreasing clump of the European C.calceolus. These are just some of thetreasures to be seen.Mrs. Edgell's garden is planned ina different way. The rocky outcropis used as a focal point to bring theeye from the riotous color of rhododendronand azalea borders with their underplantingsof native woodland plantsand ferns: Clintonia uniflora, Asarumhartwegii and A. caudatum andPhegopteris dryopteris. Many varietiesof Asiatic primulas grow with Meconopsisbetonicifolia in drifts among theshrubs and azaleas lining the grassypaths that lead up to the rocky area.The rock itself slopes down to a pool,which provides wet areas for the bogloving primulas, various caltha, andLobelia cardinalis.The rock is flanked by prostrateshrubs, hebes and Clematis alpina,along with Jasminum parkeri, Astilbechinensis, various dianthus and dwarfiris. Mat-forming plants grow well inthe rocky pockets: Gentiana acaulis,Globularia cordifolia and Dryas octopetalato name a few. Helchrysummiljordiae, flanked by Lewisia howelliigrow well in a rocky seam. Cytisuskewensis ramps down from the summit,as does C. demissus and C. procumbens.Dwarf conifers find nourishment insome of the pockets and a fine specimenof Abies koreana looks well to theright of the pool.Springtime in the Edgell garden isgay with dwarf narcissus, tulips, aconiteand fritillaria. Anemones carpet manyareas: A. nemerosa, A. ranunculoides,and A. blanda, followed by pulsatillain some lovely colors. Erythroniumsalso thrive in this garden as do variousspecies of cyclamen: CC. coum, repandum,and neapolitanum.131

<strong>Garden</strong> of Mr. and Mrs. R. H. EdgellThis garden is not nearly so easyto describe in detail as that of Mr.and Mrs. Ahiers. It's the overall effectof shrubs and trees planted to blendcolor and texture all during the yearthat gives it such a pleasing effect.Ground covers blend in with the shrubsand the very fine collection ofrhododendrons.Rejuvenating The <strong>Garden</strong>The Editor of the Alpine <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> asked Mr. Hanger, thencurator at Wisley, "How often is the rock garden soil rejuvenated orreplaced and is complete replanting of a section aimed at from timeto time?" The reply (AGS <strong>Bulletin</strong>, No. 123, p. 66) was that "Eachyear certain pockets are resoiled, as for Gentiana sino-ornate, etc.,and a generous top-dressing of sterilized soil is given annually inautumn, except to the screes. Small sections are resoiled at intervalsas necessity arises."As to a large-scale rejuvenation, Wisley's some two acres of rockgarden do present a rather extensive job. "During the war (1939-1945) many perennial weeds became established, and following (1949-1951) the entire rock garden was overhauled, a piece at a time.Certain stones were reseated where erosion had taken place. All plantsexcept a certain few large shrubs were lifted and almost all soil replaced.Then it was replanted."It is thus seen that the problems of a large public garden are nottoo different from those besetting any and all of us and that a regimeof maintenance and repair is probably something each must work outfor his own situation.—R.D.132