Connecting Collecting - Sveriges Museer

Connecting Collecting - Sveriges Museer

Connecting Collecting - Sveriges Museer

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

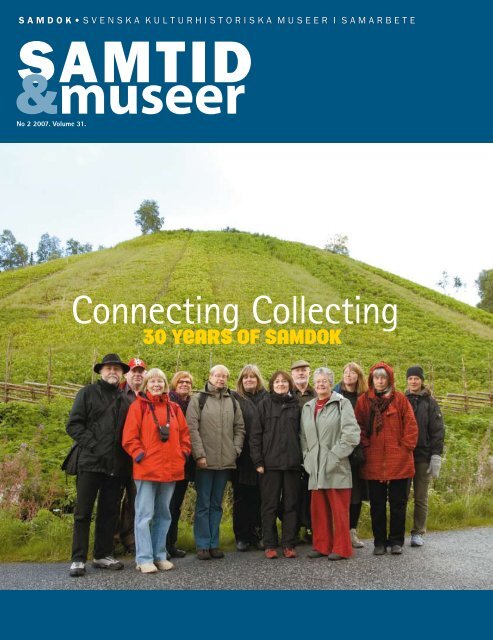

S A M D O K • S V E N S K A K U L T U R H I S T O R I S K A M U S E E R I S A M A R B E T ESAMTID&museerNo 2 2007. Volume 31.<strong>Connecting</strong> <strong>Collecting</strong>30 years of Samdok

LEADER&No 2, November 2007. Volume 31.Towards extendedcollaborationBy Christina Mattsson»Thirty years ago, the Swedishmuseums of cultural historycreated the cooperative organizationSamdok to steer attention away fromthe old peasant society towards the rapidlychanging industrial society. Withthe aid of Samdok, the museums woulddescribe the entire transition from selfsufficiencyto the information society,perhaps the most dramatic period inthe life of individuals in Sweden – thetime when people experienced morechanges in their living conditions thanany previous generation.Samdok has also argued over theyears for a more problem-orientedway of working, studying the presentday to arrive at descriptions of socialand cultural processes. It is a matter ofsuch central contemporary issues aswork and unemployment, career andexclusion, new technology and newknowledge requirements, racism andxenophobia, and so on. The aim is tofoster continuous research on everydaySwedish life.<strong>Collecting</strong> is possibly an even moreburning issue now than when Samdokwas started. The museums’ sphere ofoperation has grown, so that the scopetoday is enormous. Visitor statisticsand priority goals tend to become moreimportant than the actual collecting.Outreaching work takes over and thecollections risk being neglected. Yet thecollections are the very foundation ofthe museums’ work.The museums play an immenselyimportant role as a collective memory.2 • Samtid & museer no 2/07It is we museum employees who passjudgement on what is to be rememberedand what is to be forgotten, whatfuture generations should see. No otherinstitutions take the responsibility forpreserving material culture. The museums’collecting work is also significantfor today’s people, by observing andparticipating in contemporary processes.Museums in different parts of theworld have similar missions, and ourproblems are in general the same. Thisalso applies to the exploration of ourown times, the investigation of thingsthat we ourselves can see and experience.Documenting the present has itsspecial questions, and internationalcooperation is necessary, particularly intimes when resources are scarce.Samdok is a shared resource formuseums in Sweden, and the task ofthe Nordiska Museet as the country’sbiggest museum of cultural history isto give stability to the organization. Wenow hope that an international forumfor dialogue and collaboration on collectionmatters can be established. Theaim of this autumn’s conference is tocreate a platform for continued workalong these lines, preferably on thefoundation of the experience gained bySamdok, the network for contemporarystudies that has functioned for threedecades. pChristina Mattsson is director of the NordiskaMuseet and chair of the Samdok Councilchristina.mattsson@nordiskamuseet.seContentsTowards extended collaboration 2Christina MattssonA network for developing collectingand research 3Eva FägerborgReflecting collecting 4Eva SilvénUpdating Sweden – contemporaryperspectives on cultural encounters 6Leif MagnussonWhat’s it like at home? 8Mikael Eivergård and Johan KnutssonLeisure as a mirror of society 10Marie Nyberg and Christine FredriksenBetween preservation and change – thebuilt environment as a mirror of the times 12Barbro Mellander and Anna UlfstrandNature – an exploited heritage 14Ann-Katrin Wahss and Eva GradinPeople at work 16Charlotte Åkerman, Carin Andersson,and Ann Kristin CarlströmPublic institutions in change 18Eva Thunér-Ohlsson and Kristina StoltIn the midst of the world 20Anne Murray and Eva SilvénImages of contemporary Sweden 22ISSN 1402-3512Published by Samdok, an association of Swedish museumsof cultural history devoted to collecting, documenting, andstudying the present day.EDITED BY Eva FägerborgRESPONSIBLE EDITOR Christina MattssonCOPYRIGHT Text: Samdok/Nordiska Museet and the authors.Illustrations: The respective photographer/picture archive.Opinions are those of the authors. Unsigned contributionsare by the editor.COVER PICTURE Members of several Samdok pools at thefoot of ”Potato Hill” in Ammarnäs during the field seminar inAugust 2007. Photo Petter Engman, Västerbotten Museum.NEXT ISSUE will appear in May 2008DESIGN underhuset.comENGLISH TRANSLATION Alan CrozierPRINTED BY Ljungbergs, KlippanSAMDOKSEKRETARIATETNordiska museetBox 27820SE-115 93 StockholmTel +46 8 519 546 00Fax +46 8 5195 45 72samdok@nordiskamuseet.senordiskamuseet.se/samdok

<strong>Connecting</strong> <strong>Collecting</strong> X 30 years of SamdokA network for developingcollecting and researchBy Eva FägerborgFor thirty years, Swedish museums of cultural history haveex plored contemporary society within the framework of Samdok,the museums’ network for contemporary studies and collecting.This issue of our periodical Samtid & museer (“The Present Day &Museums”) is intended as an up-to-date presentation of Samdok’swork for an international readership.»When Samdok was established, the focuson contemporary collecting, both nationallyand internationally, broke with traditionalviews of what museums should be concernedwith. The basic tasks of cooperation in studyingpresent-day life and collecting present-day artefactsremain. In the course of time Samdok hasalso become a forum for scholarly discussions oncontemporary culture and society, a forum forprofessional development and further educationwhere we can share experiences of the empirical,methodological and theoretical dimensionsof the creation of the publicly managed and preservedcultural heritage.Organization and working methodsSamdok currently has about eighty members:county museums, central museums, municipalmuseums, and specialist museums, along withsome other institutions. The members cooperatein working groups (pools), and the core of theSamdok work is the studies and collection carriedon in the pools by the respective museums.The work is supported by the Samdok Secretariat,the Samdok Council, and Samdok’s researchcouncil.The pool system has become Samdok’sperhaps best-known characteristic. The originaltwelve groups are now eight: The group forCultural Encounters, the pools for Domestic Life,Leisure, Local and Regional Spheres, Managementof Natural Resources, Manufacture and Services,Sami Life, and Society and Politics.In recent years the pools have formulatednew guidelines/policy statements to supporttheir work. The questions, perspectives, andmethods currently being used are described inthe following articles.The Samdok Secretariat is located at andfinanced by the Nordiska Museet. As the administrativehub of the network it is responsible fordevelopment work, information, and administration.The decision-making Samdok Councilconsists of representatives of national, county,and municipal museums. The Nordiska Museet’sresearch council is now also Samdok’s scientificcouncil.In Samtid & museer (1977–96 under thetitle Samdokbulletinen) one can follow Samdok’swork and read about ongoing investigations,current research, methodological and theoreticalissues. The periodical reaches a wide audienceand is a link between the museums and othersectors of society. It appears twice a year, coveringvarying themes. Regular features alongsidethe theme articles are researchers’ diaries,presentation of new publications, and the pools’columns where they bring up topical issues forthe members.The online database Samdokregistretpresents investigations which have been done atthe member museums and reported to the secretariat.It contains details of the subjects and phenomenathat have been studied, questions andproblems, when, where, and by whom the studieswere conducted, the types of material theygenerated, and how they have been presentedand published. The source material is kept at therespective museums.Major joint seminars, conferences, andcourses are arranged by the secretariat. Autumnconferences in recent years have been devoted tovarious aspects of collecting – from the scrutinyof policy documents to discussions about therole of artefacts and the museums’ contemporarystudies in a societal perspective.International collaborationfor the futureQuestions arising today are how museums ofcultural and social history can and should studyand collect the global society. This applies bothto newly established museums and those whichmanage and expand on collections created inearlier ideological and scientific contexts. Whenthe concept of cultural heritage no longer hasa taken-for-granted local, regional, or nationalconnection, collecting must be problematized innew ways, in relation to the world and the circumstancesin which the museums act. Here weare facing a common challenge. New conditions,scientific and ethical considerations have consequencesfor collecting policies and practices, forthe cultural heritage that the museums produce.It is becoming increasingly urgent to pursue internationaldialogue and collaboration to learnabout each other’s views, methods, and experiences.In the Nordic countries we have formedthe Norsam network and we know the value ofthis kind of exchange.Samdok’s anniversary conference 2007The international perspective is the theme ofthis year’s major Samdok event, the conference<strong>Connecting</strong> <strong>Collecting</strong>, to be held at the NordiskaMuseet on 15–16 November with financialsupport from the Bank of Sweden TercentenaryFoundation. The aim of the conference is tocreate the international forum for knowledgedevelopment and collaboration that has hithertobeen lacking when it comes to collecting issues.In ICOM there are committees for the managementof museum collections, but there is nonedevoted to the considerations governing the supplyof material to the collections. We hope thatthe conference will be the starting point for aninternational network which can then be developedinto a new ICOM committee on collecting– an issue of concern for the future of museumsin all countries. pEva Fägerborg is in charge of the Samdoksecretariat at the Nordiska Museet,eva.fagerborg@nordiskamuseet.se<strong>Connecting</strong> <strong>Collecting</strong> X 30 years of Samdok»In this issueSince the periodical this time is intended togive an overview of Samdok today, it is arrangedin a different way from usual, besidesbeing published in English. This introductionis followed by a summary of two projectsconducted in recent years. The major part istaken up with articles where the pools themselvespresent their work. At the end we showpictures of contemporary Sweden, in a spreadwith examples of museums’ photo documentation.Samtid & museer no 2/07 • 3

<strong>Connecting</strong> <strong>Collecting</strong> X 30 years of SamdokReflecting collectingBy Eva Silvén»Museums not only documentwhat happens, they also creatememory and meaning, through theprocesses of defining and preservingheritage. During Samdok’s thirty yearsof existence, the member museums havecontributed to shaping the testimoniesto the history of the late 20th century.The work has recently been revised intwo projects, both published last year.The projects have followed the sameprocedure as other Samdok studies: collaborationbetween different museumsand between museums and scholars atuniversities and colleges, together withreferences to people outside the academicworld.The present day as cultural heritageFrom the 1970s, the Swedish museumsof cultural history have continuouslyconducted studies of everyday life andits changes. They constitute an extensivematerial, shaped by a professional groupwith great influence: museum staff.Through their work, they have developednorms, rules, and ways of thinking,mechanisms which still are active today.Samdok has played an important part inthis as a driving force and inspiration,but also as a discursive formation.The purpose of the project The presentday as cultural heritage: Contemporarydocumentation by Swedish museums1975–2000 was to analyse the museums’contemporary studies as regards theWhat knowledge have museum professionals created aboutlate twentieth-century society? What has been included,what has been marginalized? Two recent projects illustratethe importance of analysis, self-reflection and methodologicaldevelopment, with the aim of increasing the museums’relevance in today’s society.choice of topics, questions, methods, activitiesand results. The overall aim wasto reveal the significance of the museumsand their staff for the constructionof cultural heritage, thus increasing theirprofessional self-insight, improving theirworking methods, and broadening themuseums’ interpretation of their publicassignment.Like Samdok as a whole, the projectinvolved different kinds of museums.Seven studies illuminate the work at asmany museums spread all over Sweden.Four other studies thematically describehow museums document the present.Two of these analyse the activities fromperspectives such as work and culturalencounters, while a third considers theSamdok network from an internationalpoint of view. A fourth study discussescontemporary studies from a more personalangle.Collaborative dialoguesThe project did not just focus on theconditions for and results of the museums’activity. The seven museum studieshave also involved some methodologicalThe Magnussonfamily from Töreboda,Västergötland, intheir former kitchen,acquired by theNordiska Museet andexhibited in 1991.Photo Birgit Brånvall,© Nordiska Museet.tests. One of the studies was conductedby a group of students of museologyunder the supervision of their courseleader. The other six were carried outby museum curators in a collaborativedialogue with researchers from universitiesand colleges, who took part inseminars and meetings, in the processingof research findings, and revision ofmanuscripts.Together all the parts of the projectpaint a picture of the Swedish museums’contemporary studies and the conditionsin which they have taken place.They show that Samdok’s influence hasvaried, that belonging to a workinggroup (pool) has to a greater or lesserextent been the basis for the individualmuseum’s choice of topics and problemsfor its projects. But in each case the museumshave been forced to balance otherinterests as well – external collaborators,principals and financiers, the museum’sown plans and programmes. DespiteSamdok’s original emphasis on systematism,coordination, and comparability, itturns out that there was great scope formuseum officials to set their own stampon the studies.The project reveals that during theperiod the general aim of Samdok hasshifted from accumulating material forthe future to an increased interest inparticipating in contemporary processesand giving a voice to people in differentpositions. This raises a number of ethicalconsiderations which have to do withboth representation and preferentialright of interpretation.4 • Samtid & museer no 2/07

<strong>Connecting</strong> <strong>Collecting</strong> X 30 years of SamdokThe Difficult Matters trailer visiting the cityof Norrköping, December 1999. Photo MatsBrunander, Riksutställningar.Difficult mattersIn a parallel project such issues havebeen treated with the focus on artefactswith some kind of problematichistory: Difficult matters: Objects andnarratives that disturb and affect. Thisstarted from the reflection on whetherthe museums’ collecting really gave afull account of post-war Sweden, withboth the light and the dark sides of life.There seemed to be gaps in the artefactbasedcultural heritage. Who dared tolook for problems in seemingly innocentthings? Who saved objects that testifiedto the unmentionable and obscene, towhat was dirty, disgusting or politicallydangerous? Could those who manageour cultural heritage conceive of alsopreserving the memory of tabooed andoffensive things? It was time to examinethe museums’ collecting from an anglethat is not usually covered by activityplans and policy statements.Initially we editors aimed at a book,but underway the project became morecomprehensive. Together with Riksutställningar(The Swedish Travelling Exhibitions)a mobile exhibition, or a fieldstation, was built in a trailer that crossedSweden for almost ten months. In thetrailer there was room for 54 objectsfrom the same number of museums,each with a text about its backgroundand history. The exhibition was on showin 27 places, where visitors were invitedto contribute their own things and stories.In all, narratives from just over 300visitors were documented, from longaccounts with photographs of physicalobjects to short recollections and comments.A useful toolOf course, “difficulty” is not just somethingthat exists; it is contextually conditionedand not always obvious. It israrely a matter of a special history alongsidethe “ordinary”; difficulty is an aspectof all history writing. From this startingpoint, the task of defining what is difficult,what disturbs and affects, was leftto the museums and the visitors. Theircontributions therefore shed light onwhat is both individually and collectivelydifficult, and also the span between whatis obviously difficult and what seemsharmless. Such perspectives give the objectsa justifying ambiguity, that otherwiseseems to disappear in the museums’factual descriptions.The result of this tour was publishedlast year, a selection of 100 objects andnarratives, from museums as well asvisitors. The book’s introduction gives athorough presentation of the project as awhole, including theoretical, methodologicaland ethical considerations from aseries of seminars and other discussions.The project has also interested colleaguesoutside Sweden, and it soon became apart of the current debate on museumsand memories. The concept of “difficult”appeared to be a useful tool to put thequestion of the museums’ contemporaryrelevance on the agenda, for exampleregarding issues such as the recordingof catastrophes and major traumas. Weeditors believe that museums, as publicinstitutions, not only have a moral obligationin these processes, but also an opportunity,through the authority and theserious purpose that is usually associatedwith them.Another part of the current debate isconstituted by the postcolonial issues ofrepresentation and repatriation. Today,no museum can ignore questions suchas: Which people and phenomena arerepresented in collections, exhibitions,and other forms of cultural heritage?How can emotionally fraught issues betackled? How can evil be involved – inparticular the great crimes of history,both yesterday and today? It has becomeimpossible to speak about cultural heritagewithout simultaneously asking thequestion: Which heritage? Whose? Bothprojects, The present day as cultural heritageand Difficult matters, demonstratethe necessity for museum professionalsto continuously reflect upon what theyare doing, and what the consequencesare, for today and for the future. pEva Silvén is curator at the Nordiska Museet,eva.silven@nordiskamuseet.seReferencesSilvén, Eva & Gudmundsson, Magnus, eds.Samtiden som kulturarv: Svenska museerssamtidsdokumentation 1975–2000. Stockholm:Nordiska Museet 2006. / The present day ascultural heritage: Contemporary documentationby Swedish museums 1975–2000. With anextensive introduction and summary in English.Silvén, Eva & Björklund, Anders, eds. Svårasaker: Ting och berättelser som upprör och berör.Stockholm: Nordiska Museet 2006. / Difficultmatters: Objects and narratives that disturband affect. With an extensive introduction inEnglish.The titles can be ordered from the NordiskaMuseet: forlaget@nordiskamuseet.seSamtid & museer no 2/07 • 5

The Cultural Encounters GroupIt is time for diversity in Sweden. Cultural encounters and migrationare highly topical issues in society, and hence for museums too.The Cultural Encounters Group focuses on how the cultural encountersperspective is applied in the practical work.Updating SwedenBy Leif Magnussoncontemporary perspectives on»The situation analysis publishedby the National Council for CulturalAffairs in 2005 shows that museumsin general have both the readinessand the ambition to work with the diversityissue. In the appendix to the analysisit is noted that the museums tackle thistask in a great variety of ways. The focuscan be on the position of national minorities,on cultural phenomena connectedwith immigration or its consequences.International contacts also seem to beincreasing as a result of European integrationor via the interest in nationalmuseum collections around the world.On the other hand, it is more unusualthat museums in their exhibitions reflecton the fact that cultural encountersare a natural ingredient in all cultures, orthat the museums consider how the collectionsexemplify this.Similar ideas can be found in myarticle on “Immigration, Cultural Encounters,Ethnicity” in Samtiden somkulturarv. Svenska museers samtidsdokumentation1975–2000. (2006). Themuseums that were working with theissue then mainly focused on a kind ofmonographic perspective intended tosingle out ethnic groups and immigrantgroups. This tendency to search for distinctionshas been criticized, and thereis a constant quest for more dynamicmodels. This is very important, since oursociety has to balance the pressure ofglobalization, both the positive and thenegative consequences. If increased mobilityfor people, knowledge, and moneyis allowed to represent the good side ofglobalization, there is a bad side thatclearly involves the social and culturalissues.A harsher social climateWhat does this negative side consist of?If we look at our neighbours Denmarkand Norway, we see that the politicalmap has been redrawn in order topreserve the national community whenthe global pressure has squeezed thestrength out of the national power structures.One effect of this is that pressureincreases on the definitions of people’sstatus. Who belongs to the nationalcommunity? When can one join, andhow? Individuals are far too simply andlightly assigned to ethnic categories,which risks creating second-class citizensin the Nordic societies. The problemalso exists in Sweden, but here it ishandled differently because – comparedto our Nordic neighbours – we havereacted more weakly to the counterreactionthat globalization creates in anynation state. However, in Sweden thereis no shortage of signs of a harsher socialclimate as regards diversity.Museums that work with the presentday as cultural history are dependenton the prevailing climate of politicalopinion. When we in the Cultural EncountersGroup write in our action programmethat our work has a clear orientationto cultural policy, through theoutlook that “documenting the presentat Swedish museums is about seeingcultural encounters and migration as anindissoluble part of Sweden’s culturalhistory and social life”, we see the workin a broader context. That is our point ofdeparture.More than ethnicityThe cultural encounter perspective as atheoretical point of departure has beendiscussed since the group was foundedin 1993. The discussion has been livelyand has had the result that the group’sprogramme has been revised severaltimes. Museums which have taken partin the work over the years have had differentpurposes and goals for their participation.There has been a willingnessto bring in issues that have the emphasison other power factors than ethnicitywhen it comes to describing migrationand links to origin and place. Power factorssuch as gender, generation, sexuality,and class are always considered automaticallywhen studies are performed.It is easy enough to write this, but it isa tricky task, requiring competent andwell-trained staff. The ongoing discussionin the Cultural Encounters Group isintended to test and identify research inthe field of International Migration andEthnic Relations (IMER), post-colonialism,and the museological discussion6 • Samtid & museer no 2/07

The Cultural Encounters GroupFrom projects carried out by the MulticulturalCentre, Botkyrka.Photo Andrzej Markiewicz ©MulticulturalCentre.cultural encountersof integration and cultural heritage. Inconcrete terms, this means that researchersare invited to the group, where eachmeeting includes reading and discussionof texts. The group has also startedan international exchange of experiencewith museums and organizations workingwith cultural encounter issues, andin autumn 2006 we had a study trip toGlasgow to meet colleagues.Theme and networkIn recent years the Cultural EncountersGroup has worked with the theme of“Rites and Places of Death in MulticulturalSweden”. A special network was establishedaround the theme, coordinatedby the Multicultural Centre. The workwas carried on for several years, withseminars in different parts of Sweden. Inaddition, Samdok held a method coursegeared to the theme. The network consistedof the Cultural Encounters Groupand interested parties from museums,universities, and others concerned withthe issue. Apart from the seminars therewere some small-scale studies undertakenat different museums and a majorexhibition by the Multicultural Centre,And Then? – An Exhibition about Death.The network and its work have also beenpresented in a theme issue of Samtid &museer.The Cultural Encounters Group alsocarries on a continuous dialogue withother Samdok pools about cultural encounters.Each member of the CulturalEncounters Group acts as contact personfor a pool. Originally this mostlyinvolved highlighting cultural encounterissues and getting these into the actionprogrammes of the pools. This task hasbeen accomplished, but the step of findingfields of study, formulating importantquestions and seeking relevance inthe work of the pools is a constant itemon the agenda.When the Cultural EncountersGroup was formed, an active stancewas taken to ensure that issues concerningimmigration (there was no talk ofintegration in 1993) should affect everysphere of society, every place and individual.This was an important aim whichwas ahead of the way people thoughtat the time. In 1997 the governmentintroduced similar goals in the integrationpolicy that we know today. In otherwords, Samdok and the museums werethinking ahead of their time then – butwhat is the situation today?Updating on all frontsThe call to “Update Sweden” means thatSwedishness can appear in many differentways. The challenge for those ofus who work with the present day is toinclude and establish a contemporarySwedish self-understanding in a cultural-historyparadigm. It is a matter ofbuilding on the Swedish cultural heritage– both material and non-material. It isa matter of returning to collections withnew questions and perspectives. It is amatter of connecting the present withthe past so that new Swedes have an opportunityto understand the oddities andtraditions that have constituted Swedishness.It is a matter of writing newpages in the unfinished biography of thenational project that is Sweden. It is amatter of not dismissing the boundarycrossingand hybrid social and culturaleveryday life in which people live. Thiswork requires a cultural encounter perspectivewhich can capture pictures oftoday’s complexity. Finally, we mustcontinue to document the present inmuseums. This is the method that linksdifferent eras with the collections. It isgratifying that we have more museumstoday that are interested in these issues,and this is a sign that augurs well for theissues themselves and for Samdok. pLeif Magnusson is director of the MulticulturalCentre and former chair of the CulturalEncounters Groupleif.magnusson@mkc.botkyrka.seReferenceMagnusson, Leif. “Invandring, kulturmöten,etnicititet.” In: Silvén, Eva & Gudmundsson,Magnus, eds. Samtiden som kulturarv: Svenskamuseers samtidsdokumentation 1975–2000.Stockholm: Nordiska Museet 2006. / Thepresent day as cultural heritage: Contemporarydocumentation by Swedish museums1975–2000.Samtid & museer no 2/07 • 7

The Pool for Domestic LifeWhat’s it like at home?By Mikael Eivergård and Johan Knutsson»We live in a constantly changingand in several respects culturallyheterogeneous and pluralist society today,as expressed in a number of differentcontexts. One of these contexts is thehome. The home is also one of the traditionalcore interests of museums of culturalhistory. Most museums have collectionsthat are connected in one way oranother to the domestic sphere. There isthus a continuity on which to build, sothat contemporary studies can be placedin a “here and now” and also be relatedto the long temporal perspective that isone of the hallmarks of museums of culturalhistory.A culturally charged placeA home is a place charged with culture.In a limited area we can be confrontedwith and explore today’s social and culturaldiversity.The home is also one of the fewplaces where everyone – within certainlimits – can influence their physical environment.Shaping the home materializesa multitude of ideas, identities, andvalues. It is a physical place but also anexpression of ideas about social organization;what people belong so closely togetherthat they can share a home?According to traditional Swedishnorms, a home is ideally shared by onefamily, which in turn consists of differentsexes (man and woman) and twogenerations (parents and children), whoare expected to share a class backgroundand ethnic affiliation. Departures fromthis norm are frequently problematizedand designated in terms of mixed marriage,single-living, homo family, etc.One point of departure for the workof the pool is to view the home as a kindof concentrate of the social and culturaldiversity that is typical of our time.Home is a culturally charged word thatis full of ambiguity. Home can be a place,The Corridor. Photo © Viveca Ohlsson, Kulturen, Lund.but also a feeling. In today’s societythere are many kinds of homes; peoplelive in rented flats, terraced houses, detachedhouses, student halls of residence,health-care institutions, night shelters,or refugee centres. Others have no homeat all – homelessness is a reality. Domesticlife also displays a multitude of familyconstellations; alongside the traditionalnuclear family there are many differentforms of cohabitation, and the numberof people living on their own is alsogrowing.This diversity offers museums a fieldof study that gives access to a number ofrelevant social issues covering everythingfrom lifestyle, cultural encounters,and consumption to questions of class,generation, and gender. For the museumsin the Pool for Domestic Life theseproblems and perspectives are of vitalsignificance when we explore more preciseand concrete aspects of contemporarydomestic life in separate studies atthe respective museums or in joint seminarsand short field studies.The CorridorWhen Kulturen in Lund focused a fewyears ago on life in halls of residence, or“student corridors” as they are called,this was a study of a temporary homeshared with other people for whom itwas equally temporary. How do studentsturn a ready-furnished room on a corridorinto a home? This project set out todocument and collect material resultingin an exhibition, The Corridor. It dealt8 • Samtid & museer no 2/07

The Pool for Domestic LifeWhat kind of life is lived behind the door in the suburbs, in a residential area, or in a smallvillage in the remote forest? And what does it look like inside? The task of the Pool for DomesticLife is to explore and document people’s homes and domestic life in contemporary Sweden fromdifferent perspectives.with the way we create a sense of homein a different environment, the hall ofresidence, examining attitudes to housingand visions of the future. The projectreceived financial support from the studenthousing company AF Bostäder inLund, to mark its 50th anniversary in2004.The participating museums carry outmany projects like The Corridor, basedon the conditions and needs of the individualmuseum, and not infrequentlywith external finance. In these contextsthe Samdok organization plays a crucialpart, as support and as a soundingboard.Consuming a homeA theme that has been in the foregroundfor the work of the pool in recent years isthe home in the post-modern consumersociety. This is an interest we share withthe Pool for Leisure, which is why thetwo pools have had a number of jointmeetings and field seminars. Creatingand choosing, two of the “duties” of theconsumer society, are equally relevantfor questions of domestic life and leisure,and thus served as the point of departurefor two small-scale studies.A year ago it was about IKEA. Altogetherthe field studies in an IKEAstore in Gothenburg gave a multifacetedpicture of what steers people’s purchasesand choices. Trends in interior decorationand lifestyle, people’s views of thehome and its individual design weremixed with insights into shopping as aleisure pursuit.The bathroom as a place for enjoyment,practical functions, and interiordesign aesthetics was the theme of thisspring’s joint effort, with field studies inshops, departments stores, and homes inMalmö and Lund. Bathroom makeoversare the latest trend in interior decoration.Here consumption and do-ityourselfare combined with ideas abouta special place in the home where onecan wind down and prepare to wind upagain. With the bathroom study we alsowanted to illuminate the polarizationbetween the dream images of marketingand the factual circumstances of reality.In the bathroom it is not just a matterof changing the fixtures but perhapsabove all of giving the little space newfunctions. At least in advertising, thebathroom is represented as being simultaneouslya place for display to visitorsand a place to which you can retreat andrelax, to devote some time to yourselfafter an active day. The advertisementsfrequently talk about the bathroom interms of “a spa of your own”, and thereader is confronted with pictures offresh-looking people wrapped in bigwhite towels, chatting on the edge of thebathtub.When regarded in a slightly broaderperspective, the transformation of Swedishbathrooms is about how the newconsumerism contributes to changingthe content and meaning of the home.On the one hand, it is virtually a citizen’sduty today to consume, and possible andobligatory changes of the home are oneof the strongest incentives for the individual’sconsumption. At the same time,and this may seem paradoxical, thismass consumption gives the individualthe possibility to shape the home exactlyas he or she wants it. The home becomesa space for display, where not only aperson’s social position but also, andperhaps especially, personal identity andpreferences are expected to take shape.Refugee centre in Bräcke. Photo Björn Oskarsson©Jämtland County MuseumChangeable homesIt is at the interface between the privatehome and the social and culturalcircumstances that the Pool for DomesticLife has its field of operation. Thehome, and the family, are often perceivedas stable institutions. When theconstruction of the modern welfarestate took shape in the post-war years,the home, with the nuclear family asthe foundation of society, was one ofthe places where the political ambitionshad their most palpable expression.Rationalization was to be achieved here,good habits were to be implemented,and breaches of norms were to be combated.Today the home and the familyare phenomena that can be described asa throng of constellations and variationsof a cultural, social, ethnic, and sexualkind that teach us through their very existencethat what we tend to perceive asthe solidity of existence is in fact characterized,if not by fragility, then at least byconstant change. That is why the homeis also a culture-producing space of thegreatest importance for museums orientedto the present day. pMikael Eivergård was formerly head antiquarianat Jämtland County Museum and chair ofthe Pool for Domestic Life and is now publichealth planning officer at The Swedish NationalInstitute of Public Health,mikael.eivergard@fhi.seJohan Knutsson is curator at the NordiskaMuseet and secretary of the Pool for DomesticLife, johan.knutsson@nordiskamuseet.seSamtid & museer no 2/07 • 9

The Pool for LeisureLeisure as a mirror of societyThe Pool for Leisure works with matters concerning people’sfree time. By questioning and deconstructing leisure as aconcept and a phenomenon we can investigate changes thattake place in society and affect the individual. Leisure shouldalso be considered from the perspective of power, whichincludes gender, ethnicity, class, and generation.By Marie Nyberg and Christine Fredriksen»A basic perspective for the workof the pool is that leisure reflectsconditions in society. We are interestedin both publicly organized and individuallyshaped leisure, the commercializationof the leisure sphere and the growingexperience industry. Is post-modernleisure different, and more of a lifestylethan before? But how then does leisurefunction for the unemployed, for sicklistedpeople, children, and pension ers?How do women’s leisure activities differfrom those of men? Does everyone haveleisure?What is leisure?Leisure often used to be regarded as theopposite of work, but the concept of leisureis more complex than that. Workneed no longer be the same as gainfulemployment, and time free of work neednot be leisure. Investigating leisure requiresa multifaceted view of how peopleuse their time. Leisure is a good point ofaccess for studying the present day sinceit is constantly being renegotiated andfilled with new meanings.One way to regard leisure is to divideit into more or less free time. Wheredoes the boundary go, for example, betweenleisure activities and work in thehome? Nowadays people sometimes talkabout adjustment time, maintenancetime, and quality time to designate timefor changing focus, time for looking afterpeople or things, and time devotedto special activities. Leisure can also betime that is not at all free, with a lot ofmusts and scheduled activities.Other terms that have been introducedin recent years are “time-rich” and“time-poor”. Time-rich people are mostlyunemployed, sick-listed, and retired,in other words, groups who have a lot oftime but are not in gainful employment,and therefore do not have so muchmoney. Time-poor people have little freetime outside their salaried work but theyhave a lot of money to spend.Leisure in the form of self-chosenand pleasurable activities or non-activitiescan perhaps only be defined by theindividual based on personal experience.Leisure can thus be regarded as an arenafor self-fulfilment.“Leisure, for me that means woolly hats,anoraks and Elasta pants, and the wholefamily out in the car to drive off on someexcursion… You’re supposed to be active.Or else it’s the youth leisure centre and thatmeant drinking spirits, beer, and smokingcigarettes, at the age of twelve or so. So Ihardly ever use the word leisure, I’ve discovered.I say I’m free”, says Katinka, priest,aged 47. Photo Unni Randin-Stranne.Expanding leisureIn recent studies by the pool, the conceptof leisure has been linked to aspirationsfor life and meaningfulness, the creationof identity and the good life. The goodlife as a concept has become widespreadtoday, used both by commercial interestsand by public society. Communication,health, consumption of culture, andshopping are all elements that are supposedto contribute to creating the goodlife. This applies to the rich part of theworld…At the same time, leisure is expandingand taking an increasing amountof time and place. The arenas of leisureshow who we are. In the arena of creativity,we design and furnish our homes,and in the arena of entertainment, wheretelevision is still number one, there is anever-increasing range on offer. Activeperformance of leisure competes withthe passive reception of leisure.“Doing Samdok”The pool consists of museums with differentorientations, which gives the worka great breadth. An important part of10 • Samtid & museer no 2/07

The Pool for LeisureLeisure = spare time?Leisure life = lifestyle?Leisure ideals – for whom?the pool’s joint work is intended to raisethe level of activity among members bysustaining discussions and serving as aresource in ongoing work. Each membermuseum does studies in its own homeground, but the pool’s meetings are apossibility to ventilate and problematizetheir own studies. To elaborate on issuesof a theoretical and methodological character,we invite external lecturers andhold joint field seminars. The pool seeksdialogue not just with colleagues and researchers;just as important is the dialoguewith the general public. The Pool forLeisure also collaborates with the Poolfor Domestic Life.Work within Samdok is a way formuseums to collect contemporary narratives,photographs, and artefacts in athoroughly considered way. It is thereforean important part of the museums’present-day collecting work. Much ofthe material is used in exhibitions, programmes,and publications, thus makinguse of the collected material and obtainingresources for continued work.The pool’s member museums haverecently worked on projects to do withtopical social issues and themes concerningpeople on a personal level:Identity and its creationThe project Young People in a BorderDistrict, which Bohuslän Museum conducted2004–2006, is a Swedish-Norwegiancollaboration between museums,folk high schools, and the NordenAssociation (project Interreg III ASverige–Norge). The theme was youthand identity, border issues and conflictmanagement. What is Swedish and whatis Norwegian? What significance doesthe border have in today’s mobile society?The project marked the centennialof the break-up of the union betweenSweden and Norway in 1905, and soughtto examine how young people meet overthe border today. The results have beenpresented in theatrical performancesand exhibitions and a book has beenpublished to which young people contributedtheir narratives and thoughtsabout identity and identity creation.Meaningfulness – the good lifeWho is able to enjoy the good life? In theproject Just Like Rock and Roll, GothenburgCity Museum followed dancingcouples at Träffendansen in Kungälv.Here disabled and mentally retardedpeople meet once a month and dance tolive bands. A freshly qualified sociologistand a photographer in training werepresent at a number of dances. Theyphotographed and interviewed the participantsabout their views of dancing,socializing, and how to find a partner.Why do they find dancing so much fun?The aim was to bring out the pleasureand strength in a group that is otherwiseweak in the eyes of society. The projectresulted in an exhibition, and manydisabled people visited the museum forthe first time with pleasure, but othervisitors too felt pleasure (especially agroup of Japanese tourists who werehighly stimulated).An arena for entertainment orcreativity? The church town as acultural experienceIn northern Sweden the churches weresurrounded by houses where churchgoerscould spend the night. The longdistances that people had to travel to getto church were one of the reasons for thegrowth of these “church towns”. But howare the church towns used today? Theone in Skellefteå, known as Bonnstan or“Farmertown”, is ranked as Västerbotten’smost genuine church town and wasonce of great significance for social life.Today it consists of 116 houses with 392rooms which are privately owned. Theaim of Skellefteå Museum’s study is torecord contemporary life in a churchtown, and to find out through a questionnairesent to all the owners howthey use their rooms today. Three majorevents are held annually in Bonnstan, allof which attract thousands of visitors.The rest of the time the place offers opportunitiesfor relaxation, and the roomsare mainly used as meeting places forrelatives and friends, bringing picnicbaskets or holding parties to eat fermentedherring.Questions for the futureSweden today is a country with severaldifferent cultural identities – the traditionalSwedish leisure life is not a matterof course for new Swedes with a differentview of leisure. Taken-for-granted symbolsof leisure such as the holiday cottage,the evening class, and strolls in thecountryside may be totally alien to manypeople. The well-organized leisure that isprovided with public support is perhapsnot something that everyone wants totake part in.Other questions that the poolshould take up are who works to giveus “the good life”. What potential – inmoney and time – do they have forrewarding leisure time? The Westernworld with its quest for meaningfulnessand experiences is contrasted withwhat can be called leisure in other partsof the world. The different perspectivesthat characterize the view of leisure areimportant to bear in mind as the poolplans new studies and projects. It wouldbe fascinating to compare the practice ofleisure in Sweden with leisure in othercultures. pMarie Nyberg is curator at Gothenburg CityMuseum and chair of the Pool for Leisuremarie.nyberg@stadsmuseum.goteborg.seChristie Fredriksen is antiquarian at BohuslänMuseum, christine.fredriksen@vgregion.seSamtid & museer no 2/07 • 11

The Pool for Local and Regional SpheresBetween preservation and chanWhat traces do societalchanges leave on the physicalenvironment? That isthe overall question askedby the Pool for Local andRegional Spheres. The poolhas become an importantforum where participants canpresent ideas for projects,ongoing work, and results forshared discussions.By Barbro Mellanderand Anna Ulfstrand»In the 1970s the museums beganto work with cultural heritagemanagement, that is to say, they tookpart in community planning by identifyingphysical environments that are worthcaring and preserving. That work wasoften done separately from the museumwork with ethnology and cultural history,which in turn meant that the physicalsites were reduced to mere physical sitesand their links to non-material culturaland historical values disappeared. Oneof the pool’s most important tasks hastherefore been to serve as a forum wherethese two perspectives can be reconnected,as well as a place where scholars andpractitioners can meet.Another aspect is that the museumshave a dual role when working bothto build up knowledge and to performcultural and historic valuations. Sincethis is interesting from a museologicalperspective, the pool has included in itspolicy statement the task of scrutinizingthe selection criteria that serve as a basisfor preservation. Questions that can thenbe asked are, for example, whose culturalheritage we preserve for the future andfor whom it is preserved.From this perspective StockholmCounty Museum has examined the municipalprogramme for cultural heritagemanagement that the museum drew up,to examine how local history is presentedin it and used in the selection of sitesthat are considered worthy of preservation.It turned out that the descriptionswere free of conflict and poor innon-material traces. The programme’sassessments of the different sites centredaround three main themes: the unique,the typical, and the aesthetically pleasing.Sites that were well-preserved anduntouched by change were given thehighest status in the programme, whichmeans that narratives about how peoplehave used the sites have in many casesbeen rendered invisible.The Big City Project – assemblingknowledge about post-war buildingThe pool began its work at roughly thesame time as the project The Architectureand Cultural Environment of theBig City was launched, partly funded bythe National Heritage Board. The aimof the project was to develop work withthe built environment, especially in thesuburbs of the big cities built after 1945.Several of the pool members from local,regional, and national museums and twouniversity departments worked on theproject, and the project’s questions aboutpreservation and the user’s perspectivewere the theme of one of our first poolmeetings in Gothenburg.At this time the Swedish Museum ofArchitecture started an interview studywith many of the architects and plannerswhose work was mostly done inthe 1950s–1970s, and who had exerteda great influence on how Sweden wasplanned and built. They also interviewedsome of the people who had writtenabout the housing issue during the period.Bromölla and Södertälje – thewelfare state materializedModern industrial society has also beena theme of the pool’s work. Two majorprojects have dealt with communitiesThe welfare state is materialized. In the study of Bromöllathe Regional Museum and the director of museumsand sites in Skåne looked for the stories that buildingscan tell about a community in development and change.Photo: Ulla-Carin Ekblom©Regionmuseet Kristianstad.built up around, and depending on, largedominant industrial companies. TheRegional Museum and the director ofmuseums and sites in Skåne carried outa methodological study in the industrialcommunity of Bromölla to find out whatthe material expressions of a modernindustrial society can say about post-warpolitical, economic, and social changes.They also wanted to test new methods inthe study of the built environment. Thework did not proceed from the traditionalquestions asked in cultural heritagemanagement, which are often concernedwith the authenticity, representativeness,12 • Samtid & museer no 2/07

The Pool for Local and Regional Spheresge the built environment as a mirror of the timesPetra is busy tearing down walls to create anopen plan in the family’s newly purchasedhouse. Change was the key word whenStockholm County Museum documentedBerghem, which has developed in thirty-fiveyears from being a homogeneous to a heterogeneoushousing estate. Photo: ElisabethBoogh, Stockholm County Museum.and uniqueness of the buildings. Insteadthey looked for the stories the buildingstell about a society in development andchange. The project was carried out indialogue with inhabitants of Bromölla,which gave the museum insight intoalternative ways of understanding andremembering buildings.Stockholm County Museum, togetherwith Södertälje municipality and theStockholm County Administration, havebeen working for a couple of years withthe influence of the companies Scaniaand Astra on housing in Södertälje. Inthe post-war years the companies expandedvigorously, and being able tooffer housing was a condition for thepotential to recruit both blue-collar andwhite-collar staff. The questions askedby the study concern the companies, themunicipality, and their relations, as wellas how inhabitants of Södertälje thenand now have perceived the city andits changes. Both the Bromölla and theSödertälje studies also give a local perspectiveon the grand narrative of Swedishmodernity.From group houses to detachedhousesAnother example of a study inspired bythe pool’s policy statement is StockholmCounty Museum’s study of the Berghemhousing estate in Järfälla municipality. Abuildings antiquarian and an ethnologistcollaborated in a study of the area, whichwhen it was built at the end of the 1960sconsisted of 142 identical houses of thetype known as “WP-villa”. Today mostof the houses have been transformed indifferent ways. Many have been paintedin other colours, some have been givennew roofs or entrances. In this study thequestions concerned why the houseshad changed and what this can say abouthow society has changed in the fortyyears that have passed since the firstfamilies moved in.A street in StockholmThe pool’s policy statement also declaresthat an interesting topic is how place andidentity interact. The starting point isthat the concept of identity has changedin late modern society, which meansthat given positions and identities are increasinglyquestioned. For our pool it isof particular interest to see how identityseeking and identity formulation are relatedto the spaces, or places, where thisis enacted. How, for example, do peopleclaim the public space? How are placesaffected by the individuals and groupswho use them?Some of these questions recur in theproject Götgatan, which Stockholm CityMuseum conducted during one week inJanuary 2003. The street is mentionedfor the first time in 1494, and it has followedroughly the same course sincethen. The point of departure was thatchanges in Götgatan happen simultaneouslyin several chronological layersand at different speeds. It is both representativeand specific, both generaland unique to Stockholm. It is a partof a city and it is a local whole with abeginning and an end. The documentingteam wanted to find methods thatcould shed light on changes in the streetin the course of a day and night, as wellas more lasting phenomena. They useddifferent interview techniques: one fastwith short questions for passers-by and adeeper one with some people for whomthe street was their workplace. Theyphotographed, filmed, recorded streetnoises, and made quick notes about whathappened in the street. Posters and anumber of artefacts were collected. Thegroup, which worked virtually round theclock during the week, hopes to be ableto return at regular intervals in orderto collect material reflecting the streetand changes in street life over a longerperiod.The future of the poolTo sum up, the pool has been both usefuland pleasurable for those taking partin it. Our questions have changed overthe years, and when we revised our policystatement a couple of years ago, wenoted that much of what we thought wewere alone in discussing during the firstyears were questions that are now consideredimportant in the sector. We hopein future to be able to assemble aroundjoint projects where we can sharpen ourquestions or perhaps ask completely newquestions as society changes. pBarbro Mellander is regional director ofmuseums and sites and head of RegionmuseetKristianstad and chair of the Pool for Local andRegional Spheres,barbro.mellander@regionmuseet.m.seAnna Ulfstrand is ethnologist and photographerat Stockholm County Museum and secretary ofthe pool for Local and Regional Spheres,anna.ulfstrand@lansmuseum.a.seSamtid & museer no 2/07 • 13

The Pool for Management of Natural ResourcesNature– an exploited heritageWhat do living conditions in a village in northern Sweden have in common with silos under threatof demolition in Västergötland? What links cultural tourism with the move of a whole town? Thecommon denominator is how people use the resources provided by nature, the very preconditionsfor our survival – and the field studied by the Pool for Management of Natural Resources.By Ann-Katrin Wahss and Eva Gradin»The pool investigates and documentsthe use of nature in Sweden– land, forest, water, and minerals. Thework of the pool is closely connected tothe times and the political decisions thataffect us all. The Samdok studies illuminatehow these decisions affect peopleand the landscape and are importantboth for posterity and in contemporarysociety. This article gives some examplesof projects that have been conducted inrecent years.The consequences of our electricityneedsGallejaur is a village in the forest on theboundary between the counties of Norrbottenand Västerbotten. Here NorrbottenMuseum was commissioned by theCounty Administration in Norrbottento carry out an ethnological interviewstudy and photographic documentationduring an annual cycle, 2000–2001. Gallejaur,which in many contexts is describedas a forest village that is unique tonorthern Sweden, has been radically hitby the effects of our industrial society.The conditions for the village’s livelihooddisappeared with the construction ofthe Gallejaur power station in 1960–64.Almost all arable land and cultivated bogwas placed under water, when the lakeGallejaursjön was transformed into aregulating barrage. The shoreline camealmost 100 metres closer to the villagesettlement. Today only three farms areoccupied in the winter, but during thesummer the village comes to life, whenrelatives return to the farms that are nowholiday homes.The study focused on how the villagehas been shaped as a local culturalenvironmentsystem and was carried outto provide information for an inquiryinto the possibility of forming a culturereserve.People and their buildings was thetopic chosen in order to shed light onthe village’s development and change. Tofind causal connections between the village’sorigin, development, and presentappearance, the project involved notonly interviews with villagers but alsostudies at the Environmental Court inUmeå and the Land Survey Authority inLuleå. The study describes the developmentfrom a new settlement, marked outin 1801, to a village whose existence hasbeen radically affected by the needs forelectricity in the industrial society. Theassignment has been presented in a publicationand a travelling exhibition.At the County Administration negotiationsare now in progress with theproperty owners about compensationfor trespass, and the hope there is that adecision to make Gallejaur a culture reservecan be made during 2008.Moving a townNorrbotten Museum is also involvedin following the move of large partsof the town of Kiruna. In the comingdecade, much of the town centre has toSilo in Vara. Photo Thomas Carlquist©Västergötland Museum.be moved because a large body of ironore is to be extracted, with the risk ofundermining the buildings and causingcollapses. Here the use of natureis dramatically confronted with humanliving environments. In preparationfor the inevitable transformation ofthe town, the museum is performing asurvey and analysis during 2007 of theevaluations that different local, regional,and national actors make of the town asa cultural environment. The study willprovide a foundation for decisions thathave to be made about Kiruna’s futureurban environment.How will the move take place? Whatdo people think when they move? Whatis given priority? The pool is discussingthe possibility of holding a field seminarin Kiruna once the moving process hasgot started.The agrarian memorialsof modernismWhat happens to the buildings thatare no longer needed for agriculture?14 • Samtid & museer no 2/07

The Pool for Management of Natural ResourcesGallejaur. Photo Daryoush Tahmasebi© NorrbottenMuseum.During 2004–2005 Västergötland Museum,in collaboration with VästraGötaland Regional Museum, conducteda survey of silos, the tall storage towersfor grain that set their mark on the landscapein many places. Some silos wereinvestigated in detail, a history of thedevelopment of silos was compiled, anda survey of the current situation.This study was done in the nick oftime. In the very last minutes of 2005the agricultural organization Lantmännenproduced its own survey, OperationBlue Light, of the silos in its ownership.It shows that only a few of these “surplusbuildings” will be used in the future.Most of them will be demolished, butsome can perhaps be preserved as monumentsto a change in operations.The study of silos in western Swedenhas spawned successors in other parts ofthe country. Soon we may have a morecomprehensive survey of what Swedenlooked like before the great silo closurewas completed. What is interestingabout the silo study in western Swedenis that it put the focus on a type of buildingand agricultural activity in radicalchange. The study also created a foundationfor the decisions that have to betaken concerning these buildings in thenot too distant future.Meanings of nature for residentsand visitorsSurrounded by the Vindelfjällen naturereserve is the little community of Ammarnäs,which has gained attention forthe struggle over natural resources thathas been waged by different actors, bothlocal and non-local. Tourism has stoodagainst reindeer herding, conflicts haveraged over the rights to hunting andfishing, and relations between differentgroups have been fraught. Now solutionsare being found to the conflicts overnatural resources through local administrationand coordination in “the AmmarnäsCouncil”.To study today’s living conditions inthis village and views as to how land –the common resource – should be used,the Pool for Management of Natural Resourcesinvited other Samdok pools to afield seminar in August 2007. What arethe strategies for the village to survive,how do they see the future, what doesit mean to live in a nature reserve? Thefield seminar was organized by VästerbottenMuseum, which thereby acquireda larger circle of colleagues as partners indialogue, while simultaneously obtainingnew material.Museum farmsThe museum farms that can be foundat several museums in Sweden are alsointeresting for the work of the pool.How do the museums preserve the oldknowledge associated with the farms,and how can this be used in the presentand the future? The question of a sustainablesociety is highly relevant for allthose working with old farming techniques.The museum farms can be a bankof knowledge which could be useful ina new way in the work with tomorrow’ssociety.Cultural heritage in changeOther studies in recent years have dealtwith different aspects of agriculture.Uppland Museum, which has agricultureas one of its profile areas, hasdocumented a hypermodern byre withrobot milking facilities and is doing researchon how ideas about landscape,people, and countryside are expressedin political language, and about changesof generation and property transfers onfarms in Sweden, Estonia, and Hungary.The County Museum of Gotland iscurrently working on a project abouttourism, where farmhouse accommodationand alternative uses of outbuildingshave become new sources of income forfarmers. Another project concerns theextraction and production of lime, withthe focus on how this affects nature andthe environment.Interviews and photographic documentationfrom earlier Samdok studieshave also been used in research onagrarian history, as part of the sourcematerial for Jordbruket i välfärdssamhället1945–2000 (“Agriculture in the WelfareState”), volume 5 in a series on thehistory of Swedish agriculture (Flygare &Isacson 2003).The studies and other experiencesfrom local museum work are ventilatedcontinuously in the pool. We arrangelectures, study visits, and seminars, andthe pool serves as a resource for supplementaryeducation and networking forthe participating museums. We deal withcurrent issues and try to keep up withthe latest research. The pool for Managementof Natural Resources documentsa cultural heritage that is changing radically,and this work is very important forthe future. pAnn-Katrin Wahss is department head atVästergötland Museum and chair of the Poolfor Management of Natural Resources,ankie.wahss@vgregion.se.Eva Gradin is head antiquarian at NorrbottenMuseum, eva.gradin@nll.se.Samtid & museer no 2/07 • 15

The Pool for Manufacture and ServicesPeople at workBy Carin Andersson, Ann Kristin Carlström, and Charlotte ÅkermanThe pool for Manufacture andServices focuses on mattersconcerning people involvedin the production of physicalobjects and energy, services,media, and communication.»What our studies have in commonis the focus on people inrelation to conditions in the manufacturingindustry and the service sector.This includes the connection of workinglife to technology and technical development,new forms of organization, decision-makingprocesses and managementstrategies, consequences of changes inownership structures, and the increasedinternationalization.Basic perspectives and methodsThe changes are studied in the presentand against a historical background, sothat material from earlier studies, amongother things, can be used for comparisonin recurrent studies. What happensto occupations and tasks, to the outlookon knowledge and competence, to sociallife and relations between differentsocial and cultural categories at workplaces?What part is played, for instance,by ethnicity, generation, gender, socialgroup, and education?The studies are also intended to shedlight on the way people view their work,what influences them, and how they act.How do demands for “a good job” standup against the companies’ ambitions forrationalization and adjustment to an internationalmarket? What older featureslinger on in industry and the service sector,and how do they affect conditionstoday?Studies in the pool begin when weproblematize certain issues, and we aimat a dialogue with academic research.These issues can be documented togetherwith other actors in society throughcollaboration projects of various kinds.The possibility to cooperate, discuss andexchange experience is of great significancefor developing our knowledge ofmethod and theory.The material from the studies isvaried, consisting of recorded interviewsand written answers to questionnaires,photographs, and artefacts. We strive tocompile the material and make it accessibleto the general public in exhibitionsand publications.At the pool meetings one of the poolmuseums always acts as host institution.At the meetings we discuss how topicalsocial issues and new perspectivescan develop our work at home in themuseums. Lecturers from the researchworld are invited to talk about currentresearch which relates in different waysto matters to do with the pool’s sphereof activity. In the last few years we haveoften discussed questions about conceptssuch as outsourcing, trademarks, globaleconomies, new technology, and mobilemanufacturing. These are new questionslinked to modern industry, and we havefelt that they require a new methodologyand new ways to consider the sector ofsociety that it is our task to document inthe pool.In recent years the pool has held aseries of joint field seminars to give themembers supplementary theoretical andmethodological education and valuableknowledge of and insight into themodern-day industry and service sector.The field seminars comprise lectures,field studies, and discussions about topicsof current interest to the members ofthe pool. A couple of examples are givenbelow.How is Volvo doing?During three days in October 2004 thepool gathered in Eskilstuna to hold aBjörkdal gold mine.Operator Peter Barrljung at Björkdal.Photo Eva Fägerborg©Nordiska Museet.field seminar at the company VolvoConstruction Equipment (VCE). In totalthere were twelve participants from elevendifferent member museums from allover Sweden. The field seminar, whichwas arranged by Eskilstuna City Museumand Västmanland County Museum,was divided into a seminar day, a fieldworkday, and a day for summing up andholding a pool meeting.We viewed VCE as a suitable objectfor joint fieldwork since it is a bigcompany where both manufacture andservices are important parts of the operations.In addition, the company wasin the middle of the processes of changethat we had discussed at our meetings.Outsourcing, the increased computerizationand automation, and the growingimportance of branding were a realityhere. We were able to study and analysequestions and perspectives that felt relevantand up to date.The first day of the seminar beganwith a tour of the large factory premises.After being shown round, the groupgathered to listen to two lectures. Thefirst speaker was Jan Ekström, our host16 • Samtid & museer no 2/07

The Pool for Manufacture and ServicesAt Volvo Construction Equipment.Photo Roy Cassé©Västmanland CountyMuseum.In the realm of goldThe field seminar in autumn 2005 wasabout a highly topical subject: mining.Rising prices for gold and other mineralshave led to constant expansion in prospectingand mining.The host for the pool’s field seminarin Västerbotten was Skellefteå Museum,which had arranged a varied programmewith study trips to the museum, fieldworkat the Björkdal mine, a guided tourof Bergrum Boliden – Boliden’s museumof mining and minerals, pleasant lunches,dinners, and overnight stays in anarea which has now become a part of theregion’s tourist and experience industryand which is marketed in English underthe name “Gold of Lapland”. Staff at themuseum also produced reading materialfor the seminar participants.The programme began with a showingof the exhibitions in SkellefteåMuseum. We spent the afternoon inthe Björkdal mine, where the operationswere presented. It was a study tripthat the group made to get an idea ofthe work in the mine. On the followingmorning we met the managementof the mine and then did interviewswith employees. The interviews weretape-recorded and transcribed when themembers of the pool had returned hometo their own workplaces. The transcribedinterviews with contextual details werethen sent to the host museum, whichthus acquired a corpus of complete newmaterial for its archive.at Volvo, who told us about VCE as acompany. Then Professor Gösta Arvastsonfrom the Department of Anthropologyand Ethnology at Uppsala Universitylectured about his research on workersat Volvo and other vehicle industries.The day ended with a discussion basedon our impressions of what we had seenand heard during the lectures and companypresentation.The second day was devoted to fieldwork.We worked in groups of two orthree persons and each group chose foritself which themes and questions towork with. The group also had to thinkof suggestions as to artefacts to acquire.The actual fieldwork consisted chiefly ofinterviews with pre-selected informantsfrom different parts of the company andto a certain extent also of photographicdocumentation, observation, and fieldnotes.On the third and last day the groupspresented their fieldwork and discussedthe experience gained during the fieldwork,both new knowledge about workat Volvo and also the method itself.New questions popped up duringthe fieldwork and were reflected in thereports. The relatively new principle “sellone – make one” and the new organizationin which former departments werenow outsourced companies entailed newways of working. The increased computerizationalso led to changes in thework. Today there are totally new requirementsfor all employees to be ableto read and write Swedish and English,and it is no longer just a matter of workingwith one’s hands.An important networkDocumenting manufacture and servicesis a current issue for many Swedish museumsboth at the national level and onthe regional and local levels. The pooltherefore has a large number of members,even if they have not all been ableto work as actively with this as theywould have wished. The field seminarsare highly appreciated as occasions forthe pool members to meet and togetherelaborate on matters concerning bothcontent and method. In their day-to-daywork the members of the pool are occupiedwith many different tasks and arenot infrequently alone in doing Samdokstudies within the framework of their respectivemuseums. The pool meetings arethus an opportunity for the members tolearn from each other’s experience. pCarin Andersson is antiquarian at EskilstunaCity Museum, carin.andersson@eskilstuna.seAnn Kristin Carlström was formerly head ofresearch at the Museum of Work and is nowdirector of Skoklosterannkristin.carlstrom@lsh.seCharlotte Åkerman is antiquarian at Kulturenin Lund and chair of the pool for Manufactureand Services,charlotte.akerman@kulturen.comSamtid & museer no 2/07 • 17

The Pool for Society and PoliticsPublic institutions in changeBy Eva Thunér Ohlsson and Kristina Stolt»Originally this was called thePublic Pool, and from the beginningour task was to study institutionsexercising public authority. Today oursphere is much wider, encompassingthe political and public sides of people’slives. The studies comprise phenomenain society that are reflected in the actionsof the state, regions, and municipalities,but we also take an interest in groupsand individuals who seek to affect publiclife.Decisions in parliament, countycouncils, and local councils create regulationsfor the life and actions of citizens,but market forces, opinion moulders,trendsetters, and non-profit groups arealso important actors. How this happens,with what methods, and what the consequencesare for the citizens is the focusof the pool’s interest. In these contextsthe citizens have many different roles –voters, elected representatives, professionals,the unemployed, early retirementpensioners, club members, schoolpupils, company leaders, employees, taxpayers,etc. – which must also be madeclear in our work.Some of the current social issues thathave been discussed in recent years andconsidered in the museums’ studies arethe restructuring of the public sector,the changed role and organization of thenational defence, integration policies,Sweden’s membership of the EU, and themulti-religious Sweden.Museums big and smallThe pool at present has eighteen members,most of which come from majorinstitutions with national or countyresponsibility, but some museums arereally small, with only one or two employees.The medical history group, which isone of the small museums, always has aHealth care, school, defence, police, and public administrationare some of the areas that interest the Pool for Society andPolitics. It is concerned with the significance of the institutionsfor society as a whole and for the individual, and with our wayof looking at society and each other.meeting of its own in connection withthe pool meeting. Here they ventilatetheir specific issues, which are oftenrelated to the fact that these museumsmostly were established on private initiativeand the collections are often ownedby associations run with grants from acounty council or a municipality. Themedical history group has been decimatedsince museums have been putin mothballs – a clear example showingthat changes in society and politicalpriorities are a part of everyday realityfor the pool members.MeetingsThe pool meets twice a year. Apart fromthe formal meeting we always have alecturer on a topic of current concern tothe pool. Practical questions of copyrightand ethical issues about the publicationof collected material, for example, fromminors, have been discussed. These areproblems that we all have in common.Reports about ongoing and plannedprojects in the museums are e-mailedto the members before the meeting andthen appended to the minutes for thearchive. We gain time in that the participantscan read the texts before themeeting and can bring up questions andthoughts about the projects.Working methodsThe pool also aims to develop the members’professional role. To do so, thisspring we conducted a field study inmini-format for half a day in the newentrance to the Södra Älvsborg Hospitalin Borås. We did both participantobservation and short interviews tosee how visitors acted and to hear whatthey thought of the entrance. Had theintentions of the hospital managementbeen fulfilled? The head of premises atthe hospital had prepared us by informingabout the work on the programme,the architectural competition, and theconstruction of the entrance. In all itssimplicity, this gave us cause to reflect onthe working methods and formulation ofquestions.Another of our intentions is tocarry out small-scale studies in differentplaces at the same time, for example,the new citizenship ceremonies that haveemerged in many municipalities. At themeetings we can then discuss methods,the selection of artefacts, the use ofpictures, and such matters based on theexperience we have gained.Active participationThe members’ active participation iscrucial for the implementation of ournew policy statement from 2006. Eachmuseum conducts studies within itsown sphere of responsibility. Thesetasks often compete with other museumwork. It is important to get the museummanagement’s support but also toground the Samdok work in the museums’steering documents and politicalleadership, both so that we can be giventhe time and resources for our work andso that we can take part in pool meet-18 • Samtid & museer no 2/07

The Pool for Society and Politicsings. The resources vary greatly betweenthe museums.An example of how a small museumcan work with the policy statementcomes from the museum of medical history,museet.då.nu, in Borås:Definitions of health on notice board inmuseet.då.nu. “Health is to live here andnow! not yesterday or tomorrow!”Photo Anna C Lindqvist© Södra ÄlvsborgsSjukhus, Borås. 37From the project Voices in Nyköping. Youand Me 1+1=1. Photo Carolin Sellman,May 2007.How we define healthMuseet.då.nu opened in new premisesin the middle of the newly built entranceto the hospital in Borås in autumn 2004.In the museum one meets a big noticeboard with the question “What doeshealth mean to you?” For nearly threeyears now the visitors have given theirdefinitions of what health means. Theslips of paper are continually changedand archived by the museum.Apart from all the people who havemade things easy for themselves andanswered “Everything”, “Being healthy”,“Feeling well”, and so on, there is a categorythat is more common than others,the one where people refer to love orrelations. They stress that the perceptionof one’s own health is dependent on one’snearest and dearest also feeling well, thatone belongs to other people in a giveand-takerelationship. Work also comesin here. Having a job and being able towork is considered to be both an endand a means to good health.Many answers are connected to theconcept of joy, satisfaction, and happiness.Here the whole spectrum is represented,from quite modest wishes tobe happy, to demands to be completelywithout worries.Others write about having time forreflection, having the strength to livetoday’s stressful life, the desire for peaceand quiet. An interesting area is bodyand soul. Several people say that youcan be healthy even if the body does notwork perfectly, as long as the soul or themind feels all right. Some people emphasizethe importance of mental balance.These are some examples of thethoughts expressed when people answeredthe museum’s question aboutwhat health means. Presumably, if onelet people answer the question over alonger period of time, one could also seechanges in the character of the answersdepending on the prevailing debateabout health, and on how the social climateotherwise changes.Interviews with the people ofNyköpingSörmland Museum, which is a countymuseum located in Nyköping, is currentlyrunning the project Voices inNyköping. Here the town’s inhabitantsfrom all over the world say what theythink is important for them in theirlives. The aim is to broaden the way oflooking at what it is to be a human being,what Nyköping is and has been,urgent issues here and now, and whathistory is and means.Right now we are interviewing agreat many people in Nyköping of differentages and in different roles. We askwhat is important for them right now.We want to bring out different lives andbackgrounds and illuminate how theyall, with their differing experiences,contribute to the life of the city, its developmentand historiography. The answerswill be presented on long lengthsof cloth, hanging along familiar routeswhere people walk in Nyköping, bothindoors and outdoors.One part of the project has alreadybeen shown in the city’s shopping malls.High-school pupils from the TessinSchool, who have chosen to study Mediaand Communication, have photographedtheir coevals and written texts,and the museum has had fourteen ofthese printed on hangings.Monitoring the world around usFor the pool it is important to be observantabout tendencies in the surroundingworld. It is essential, for example,to see what is taken up in futures studiesand in publications from different actorsof interest for our field of activity. Theaim of the pool for Society and Politicsmust always be to explore processes ofchange in society, to see their effects andpatterns. pEva Thunér-Ohlsson is head antiquarian atSörmland Museum and chair of the pool forSociety and Politics, eva.thuner.ohlsson@dll.seKristina Stolt is curator at museet.då.nu inBorås, kristina.stolt@vgregion.seSamtid & museer no 2/07 • 19