Diversity of Small Mammals in the Pacific Coastal Desert of Peru ...

Diversity of Small Mammals in the Pacific Coastal Desert of Peru ...

Diversity of Small Mammals in the Pacific Coastal Desert of Peru ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

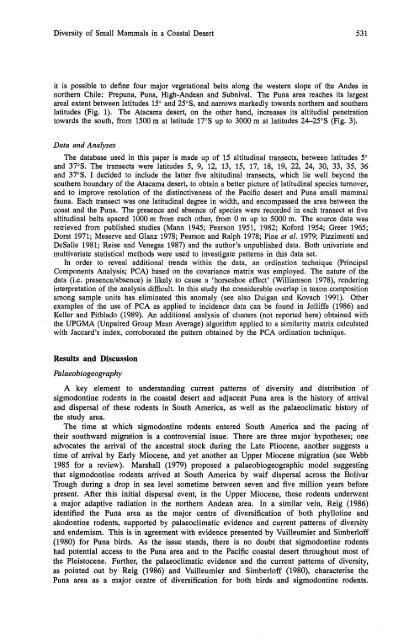

<strong>Diversity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Mammals</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>Desert</strong>it is possible to def<strong>in</strong>e four major vegetational belts along <strong>the</strong> western slope <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Andes <strong>in</strong>nor<strong>the</strong>rn Chile: Prepuna, Puna, High-Andean and Subnival. The Puna area reaches its largestareal extent between latitudes 15" and 25"S, and narrows markedly towards nor<strong>the</strong>rn and sou<strong>the</strong>rnlatitudes (Fig. 1). The Atacama desert, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>in</strong>creases its altitudial penetrationtowards <strong>the</strong> south, from 1500 m at latitude 17"s up to 3000 m at latitudes 24-25"s (Fig. 3).Data and AnalysesThe database used <strong>in</strong> this paper is made up <strong>of</strong> 15 altitud<strong>in</strong>al transects, between latitudes 5"and 37"s. The transects were latitudes 5, 9, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, 19, 22, 24, 30, 33, 35, 36and 37"s. I decided to <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong> latter five altitud<strong>in</strong>al transects, which lie well beyond <strong>the</strong>sou<strong>the</strong>rn boundary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Atacama desert, to obta<strong>in</strong> a better picture <strong>of</strong> latitud<strong>in</strong>al species turnover,and to improve resolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ctiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> desert and Puna small mammalfauna. Each transect was one latitud<strong>in</strong>al degree <strong>in</strong> width, and encompassed <strong>the</strong> area between <strong>the</strong>coast and <strong>the</strong> Puna. The presence and absence <strong>of</strong> species were recorded <strong>in</strong> each transect at fivealtitud<strong>in</strong>al belts spaced 1000 m from each o<strong>the</strong>r, from 0 m up to 5000 m. The source data wasretrieved from published studies (Mann 1945; Pearson 1951, 1982; K<strong>of</strong>ord 1954; Greer 1965;Dorst 1971; Meserve and Glanz 1978; Pearson and Ralph 1978; P<strong>in</strong>e et al. 1979; Pizzimenti andDeSalle 1981; Reise and Venegas 1987) and <strong>the</strong> author's unpublished data. Both univariate andmultivariate statistical methods were used to <strong>in</strong>vestigate patterns <strong>in</strong> this data set.In order to reveal additional trends with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> data, an ord<strong>in</strong>ation technique (Pr<strong>in</strong>cipalComponents Analysis; PCA) based on <strong>the</strong> covariance matrix was employed. The nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>data (i.e. presence/absence) is likely to cause a 'horseshoe effect' (Williamson 1978), render<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> analysis difficult. In this study <strong>the</strong> considerable overlap <strong>in</strong> taxon compositionamong sample units has elim<strong>in</strong>ated this anomaly (see also Duigan and Kovach 1991). O<strong>the</strong>rexamples <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> PCA as applied to <strong>in</strong>cidence data can be found <strong>in</strong> Jolliffe (1986) andKeller and Pitblado (1989). An additional analysis <strong>of</strong> clusters (not reported here) obta<strong>in</strong>ed with<strong>the</strong> UPGMA (Unpaired Group Mean Average) algorithm applied to a similarity matrix calculatedwith Jaccard's <strong>in</strong>dex, corroborated <strong>the</strong> pattern obta<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> PCA ord<strong>in</strong>ation technique.Results and DiscussionPalaeobiogeographyA key element to understand<strong>in</strong>g current patterns <strong>of</strong> diversity and distribution <strong>of</strong>sigmodont<strong>in</strong>e rodents <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> coastal desert and adjacent Puna area is <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> arrivaland dispersal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se rodents <strong>in</strong> South America, as well as <strong>the</strong> palaeoclimatic history <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> study area.The time at which sigmodont<strong>in</strong>e rodents entered South America and <strong>the</strong> pac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>ir southward migration is a controversial issue. There are three major hypo<strong>the</strong>ses; oneadvocates <strong>the</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancestral stock dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Late Pliocene, ano<strong>the</strong>r suggests atime <strong>of</strong> arrival by Early Miocene, and yet ano<strong>the</strong>r an Upper Miocene migration (see Webb1985 for a review). Marshall (1979) proposed a palaeobiogeographic model suggest<strong>in</strong>gthat sigmodont<strong>in</strong>e rodents arrived at South America by waif dispersal across <strong>the</strong> BolivarTrough dur<strong>in</strong>g a drop <strong>in</strong> sea level sometime between seven and five million years beforepresent. After this <strong>in</strong>itial dispersal event, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Upper Miocene, <strong>the</strong>se rodents underwenta major adaptive radiation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Andean area. In a similar ve<strong>in</strong>, Reig (1986)identified <strong>the</strong> Puna area as <strong>the</strong> major centre <strong>of</strong> diversification <strong>of</strong> both phyllot<strong>in</strong>e andakodont<strong>in</strong>e rodents, supported by palaeoclimatic evidence and current patterns <strong>of</strong> diversityand endemism. This is <strong>in</strong> agreement with evidence presented by Vuilleumier and Simberl<strong>of</strong>f(1980) for Puna birds. As <strong>the</strong> issue stands, <strong>the</strong>re is no doubt that sigmodont<strong>in</strong>e rodentshad potential access to <strong>the</strong> Puna area and to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> coastal desert throughout most <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Pleistocene. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> palaeoclimatic evidence and <strong>the</strong> current patterns <strong>of</strong> diversity,as po<strong>in</strong>ted out by Reig (1986) and Vuilleumier and Simberl<strong>of</strong>f (1980), characterise <strong>the</strong>Puna area as a major centre <strong>of</strong> diversification for both birds and sigmodont<strong>in</strong>e rodents.