Diversity of Small Mammals in the Pacific Coastal Desert of Peru ...

Diversity of Small Mammals in the Pacific Coastal Desert of Peru ...

Diversity of Small Mammals in the Pacific Coastal Desert of Peru ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

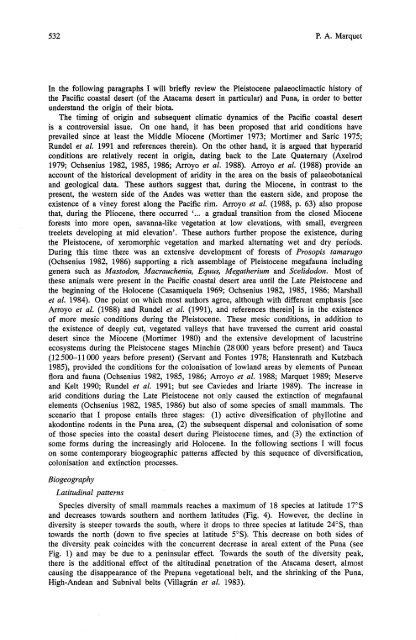

P. A. MarquetIn <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g paragraphs I will briefly review <strong>the</strong> Pleistocene palaeoclimactic history <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> coastal desert (<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Atacama desert <strong>in</strong> particular) and Puna, <strong>in</strong> order to betterunderstand <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir biota.The tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> orig<strong>in</strong> and subsequent climatic dynamics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> coastal desertis a controversial issue. On one hand, it has been proposed that arid conditions haveprevailed s<strong>in</strong>ce at least <strong>the</strong> Middle Miocene (Mortimer 1973; Mortimer and Saric 1975;Rundel et al. 1991 and references <strong>the</strong>re<strong>in</strong>). On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, it is argued that hyperaridconditions are relatively recent <strong>in</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>, dat<strong>in</strong>g back to <strong>the</strong> Late Quaternary (Axelrod1979; Ochsenius 1982, 1985, 1986; Arroyo et al. 1988). Arroyo et al. (1988) provide anaccount <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> historical development <strong>of</strong> aridity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> palaeobotanicaland geological data. These authors suggest that, dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Miocene, <strong>in</strong> contrast to <strong>the</strong>present, <strong>the</strong> western side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Andes was wetter than <strong>the</strong> eastern side, and propose <strong>the</strong>existence <strong>of</strong> a v<strong>in</strong>ey forest along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> rim. Arroyo et al. (1988, p. 63) also proposethat, dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Pliocene, <strong>the</strong>re occurred '... a gradual transition from <strong>the</strong> closed Mioceneforests <strong>in</strong>to more open, savanna-like vegetation at low elevations, with small, evergreentreelets develop<strong>in</strong>g at mid elevation'. These authors fur<strong>the</strong>r propose <strong>the</strong> existence, dur<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> Pleistocene, <strong>of</strong> xeromorphic vegetation and marked alternat<strong>in</strong>g wet and dry periods.Dur<strong>in</strong>g this time <strong>the</strong>re was an extensive development <strong>of</strong> forests <strong>of</strong> Prosopis tamarugo(Ochsenius 1982, 1986) support<strong>in</strong>g a rich assemblage <strong>of</strong> Pleistocene megafauna <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>ggenera such as Mastodon, Macrauchenia, Equus, Mega<strong>the</strong>rium and Scelidodon. Most <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se animals were present <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> coastal desert area until <strong>the</strong> Late Pleistocene and<strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Holocene (Casamiquela 1969; Ochsenius 1982, 1985, 1986; Marshallet al. 1984). One po<strong>in</strong>t on which most authors agree, although with different emphasis [seeArroyo et al. (1988) and Rundel et al. (1991), and references <strong>the</strong>re<strong>in</strong>] is <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> existence<strong>of</strong> more mesic conditions dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Pleistocene. These mesic conditions, <strong>in</strong> addition to<strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> deeply cut, vegetated valleys that have traversed <strong>the</strong> current arid coastaldesert s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> Miocene (Mortimer 1980) and <strong>the</strong> extensive development <strong>of</strong> lacustr<strong>in</strong>eecosystems dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Pleistocene stages M<strong>in</strong>ch<strong>in</strong> (28000 years before present) and Tauca(12500-11 000 years before present) (Servant and Fontes 1978; Hanstenrath and Kutzbach1985), provided <strong>the</strong> conditions for <strong>the</strong> colonisation <strong>of</strong> lowland areas by elements <strong>of</strong> Puneanflora and fauna (Ochsenius 1982, 1985, 1986; Arroyo et al. 1988; Marquet 1989; Meserveand Kelt 1990; Rundel et al. 1991; but see Caviedes and Iriarte 1989). The <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>arid conditions dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Late Pleistocene not only caused <strong>the</strong> ext<strong>in</strong>ction <strong>of</strong> megafaunalelements (Ochsenius 1982, 1985, 1986) but also <strong>of</strong> some species <strong>of</strong> small mammals. Thescenario that I propose entails three stages: (1) active diversification <strong>of</strong> phyllot<strong>in</strong>e andakodont<strong>in</strong>e rodents <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Puna area, (2) <strong>the</strong> subsequent dispersal and colonisation <strong>of</strong> some<strong>of</strong> those species <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> coastal desert dur<strong>in</strong>g Pleistocene times, and (3) <strong>the</strong> ext<strong>in</strong>ction <strong>of</strong>some forms dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly arid Holocene. In <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g sections I will focuson some contemporary biogeographic patterns affected by this sequence <strong>of</strong> diversification,colonisation and ext<strong>in</strong>ction ptocesses.BiogeographyLatitud<strong>in</strong>al patternsSpecies diversity <strong>of</strong> small mammals reaches a maximum <strong>of</strong> 18 species at latitude 17"sand decreases towards sou<strong>the</strong>rn and nor<strong>the</strong>rn latitudes (Fig. 4). However, <strong>the</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>diversity is steeper towards <strong>the</strong> south, where it drops to three species at latitude 24"S, thantowards <strong>the</strong> north (down to five species at latitude 5"s). This decrease on both sides <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> diversity peak co<strong>in</strong>cides with <strong>the</strong> concurrent decrease <strong>in</strong> areal extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Puna (seeFig. 1) and may be due to a pen<strong>in</strong>sular effect. Towards <strong>the</strong> south <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> diversity peak,<strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong> additional effect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> altitud<strong>in</strong>al penetration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Atacama desert, almostcaus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> disappearance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prepuna vegetational belt, and <strong>the</strong> shr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Puna,High-Andean and Subnival belts (Villagr<strong>in</strong> et al. 1983).