Theatre Today: Where Can You Find It?

Theatre Today: Where Can You Find It?

Theatre Today: Where Can You Find It?

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

11<br />

THE THEATRE OF TODAY EXISTS onstage, not in the pages of this or any other book. The theatre of today is<br />

being performed right now, in the multi-million-dollar theatres of the world’s great cities as well as on simpler<br />

stages at schools, community theatres, nightclubs, roadhouses, and experimental theatre clubs everywhere.<br />

The theatre of today is all around us, waiting to be discovered, seen, heard, felt, and experienced. The best<br />

way to tap into its fundamental impulse is to go out and see it.<br />

What’s Happening?<br />

<strong>It</strong>’s not easy to say what’s happening in the theatre today. We cannot evaluate the current theatre with the<br />

same objectivity that we bring to the theatre of the past — even the recent past. <strong>Theatre</strong> is a business as well<br />

as an art, and the promotion, publicity, and puffery that surround each current theatrical success make a<br />

cool perspective diffi cult. <strong>Where</strong>as poets and painters are often ignored until years following their deaths,<br />

the opposite is more often true of theatre artists: they may be lionized in their own time and forgotten a few<br />

years later. A permanent place in the repertory of world theatre is the achievement of very few; among the<br />

playwrights once deemed equal to Shakespeare are such dimly remembered fi gures as John Fletcher, Joseph<br />

Addison, and Maxwell Anderson. Which of our present-day writers and actors and other theatre artists will<br />

achieve more than ephemeral glory? Which, if any, will leave a mark on future generations? No one can answer<br />

either question with any certainty.<br />

253

From a practical point of view — looking at stage<br />

practice rather than theory — theatre is a fairly conservative<br />

institution. <strong>Theatre</strong> companies around the<br />

world present plays from the past as well as from their<br />

own time and also conserve many of the theatre’s traditional<br />

ways of working. Nearly all the plays mentioned<br />

in the previous chapters will be performed<br />

somewhere in the world this season, and the vigorous<br />

debates among today’s actors and directors often<br />

repeat dialogues from the days of Aristophanes,<br />

Shakespeare, and Stanislavsky. Nevertheless, in the<br />

twenty-fi rst century, a new era seems to be emerging.<br />

The previous century was a violent one: two world<br />

wars and one cold war, assassinations of political and<br />

cultural leaders (Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther<br />

King, Jr., John and Robert Kennedy, Anwar Sadat, Yitzhak<br />

Rabin, John Lennon), Nazi and nuclear holocausts,<br />

the proliferation of alluring but dangerous<br />

drugs and sex-linked diseases, and the threatened destruction<br />

of Earth’s vital resources. The arts responded<br />

to these social changes with an artistic freedom often<br />

frightening in its extremity — nowhere more so than<br />

in the theatre, where by the 1970s Dionysian ecstasy<br />

had returned to the stage with a force almost equal to<br />

that of the ancient dithyramb. As play-licensing laws<br />

fell in England and legal censorship became locally<br />

unenforceable in America, profanity, nudity, at least<br />

simulated copulation, violence, and libelous accusation<br />

— all unknown on the legitimate stage since ancient<br />

times — became almost commonplace. Plays<br />

popular in America in the last third of the twentieth<br />

century included one accusing the sitting president<br />

of murder (MacBird), another accusing a recent pope<br />

of genocide (The Deputy), another featuring a farm<br />

boy copulating with his pig (Futz), another featuring<br />

teenage boys stoning a baby to death in its crib (Saved),<br />

and another that concluded with the actors and some<br />

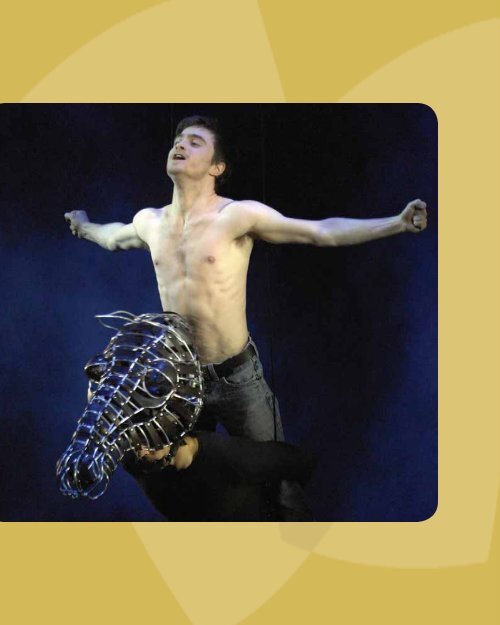

Nudity had fi rmly entered serious mainstream theatre by 1973, when Peter<br />

Shaffer’s Equus proved a solid success at London’s National <strong>Theatre</strong> and<br />

then received a Tony best-play award for its Broadway version. Based on<br />

a true story, Shaffer’s play treats an engaging but disturbed teenage boy,<br />

Alan Strang, whose passion for horses has displaced his more conventional<br />

sexual development. Equus (Latin for “horse”) achieves its astonishing climax<br />

when, totally naked in a horse barn, Alan fails to consummate an impromptu<br />

sexual encounter with an equally naked girl and, in a fi t of maniacal despair,<br />

blinds the onlooking “horses” with a hoof pick. The play’s immensely successful<br />

2007 London revival, with Daniel Radcliffe (widely known for his<br />

fi lm roles as Harry Potter) as Alan, made clear that staged nudity, though<br />

perhaps no longer shocking, retains its tremendous power to create an<br />

intense theatrical impact. Thea Sharrock directed.<br />

254 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

of the audience undressing and marching naked out<br />

into the street (Paradise Now). Some of this Dionysian<br />

frenzy reached right into the theatre’s mainstream<br />

when the rock Broadway musical Hair (1968) ended<br />

its fi rst act with its actors — who had already sung rapturously<br />

about sodomy, fellatio, and cunnilingus —<br />

brazenly stripping off their clothes and facing the<br />

audience in a posture of mocking defi ance.<br />

Nor were theatre audiences themselves immune<br />

from such changes in theatrical convention. In the experimental<br />

theatre of the 1970s and 1980s, spectators<br />

almost routinely found themselves sat upon, fondled,<br />

assaulted, hurled about, handed lit joints (of marijuana),<br />

and, in at least one case (in Finland), urinated<br />

upon. These and other extreme behaviors had become

part of the license claimed by a theatre purportedly<br />

trying to make itself heard above the societal din of<br />

war, riots, and corruption. Or, as many asked, were its<br />

adherents merely “acting out” to get attention? In<br />

any event, it was an era of dramaturgical violence<br />

and abandon that brought the age of “modernism”<br />

to a crisis, if not to a conclusion.<br />

Well before the century’s end, however, this mood<br />

of violent protest was largely spent. Profanity and<br />

nudity no longer seemed novel and, having lost their<br />

power to shock, became new tools for addressing serious<br />

social issues not only in the theatre’s experimental<br />

avant-garde but on its mainstream stages, both<br />

academic and professional.<br />

And just what were those social issues? Foremost<br />

among them were assaults on longtime (and largely<br />

knee-jerk) prejudices and privileges associated with<br />

gender, race, class, and sexual orientation that came<br />

under fi re in various movements — civil rights, women’s<br />

and gay liberation, ethnic pride — that began in<br />

earnest in the 1960s and gained breadth and depth<br />

in succeeding decades. By the turn of the twenty-fi rst<br />

century, at least half the new plays appearing on<br />

American stages touched on, or were even devoted to,<br />

issues that those movements had brought to public<br />

consciousness.<br />

On the international scene, the end of the twentieth<br />

century saw an explosion of new social and political<br />

alignments and an often overwhelming spectrum<br />

of new technologies. With the cold war ended and its<br />

empires and alliances dissolved or reconfi gured, the<br />

newly globalized economy challenged local cultures<br />

with enhanced but often troubling prospects, and<br />

astonishing advances in telecommunications — e-mail,<br />

weblogs, satellite telecasting, text-messaging, and cell<br />

phones — revolutionized the way the world’s populations<br />

were interconnecting. A mere year into the<br />

new millennium, whatever political stability seemed<br />

to have been achieved at the century’s end was staggered<br />

by a terrorist attack on New York and Washington<br />

that was said to have “changed everything”<br />

and that soon led, if indirectly, to military invasions,<br />

In Nicolas Kent’s Guantánamo, staged in 2004 at the Tricycle <strong>Theatre</strong> in London, William Hoyland plays U.S. defense secretary<br />

Donald Rumsfeld, and Paul Bhattacharjee (lying down) and Daniel Cerqueir play detainees at the U.S. naval-base prison in Cuba.<br />

What’s Happening? 255

suicide bombings, regime changes, civil wars, insurrections,<br />

threats of nuclear proliferation, and what<br />

was described as a “global war on terror” fueled by<br />

military, economic, and religious imperatives.<br />

The theatre — a tool of live communication — has<br />

responded quickly to a vast store of new subjects and<br />

fresh opportunities. Once again, as in the days of the<br />

ancient Greeks and Shakespearean England, the stage<br />

has surfaced as an arena in which new thoughts, fashions,<br />

feelings, morals, theologies, and aesthetics can<br />

be enacted, and new technologies explored, in order<br />

to bring lucidity and structure to the confusions that<br />

beset us all.<br />

Although generalizations about an era still upon<br />

us must be tentative, some major themes have clearly<br />

emerged in today’s theatre, and we look at several of<br />

them in the ensuing pages.<br />

� A <strong>Theatre</strong> of Postmodern Experiment<br />

The term postmodernism indicates a way of thinking,<br />

or even nonthinking, more than it refers to a particular<br />

historical period. The postmodern defi es any<br />

comprehensive analysis because it essentially defi es<br />

the act of analyzing. Dismissing logic and cause-andeffect<br />

determinism, the postmodern impulse replaces<br />

both with parallel, almost random, refl ections. These<br />

are of two sorts: self-refl ections, whereby a work of<br />

art pays homage to itself, and refl ections of the past,<br />

whereby a work of art absorbs and refashions earlier<br />

models in our own image. The fi rst form of postmodernism<br />

is evident in surrealist René Magritte’s<br />

painting of a pipe, which sports the legend “Ceci n’est<br />

pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”) below the pipe’s<br />

image, the legend thus serving as a refl ection of the<br />

painting in the painting. The second form of postmodernism<br />

may be seen in Andy Warhol’s repeated<br />

and repainted images of Campbell’s soup cans, electric<br />

chairs, and head shots of Marilyn Monroe, which, instead<br />

of repudiating the past as modernism seeks to<br />

do, embrace, quote, and recycle it. Time magazine’s<br />

2006 “Person of the Year” cover story, which named<br />

“<strong>You</strong>” as the recipient of its coveted citation, was<br />

conveyed by a Mylar mirror pasted to the magazine’s<br />

cover: in the twenty-fi rst century, we are our own role<br />

models.<br />

A postmodernist work of art is not about “something”<br />

so much as it is about itself — about “art” — and<br />

about ourselves — about “us.” Such a work might be<br />

said to “deconstruct” itself so as to make us think as<br />

much about the idea of art, and the idea of ourselves,<br />

256 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

as we think about what we’re seeing. How do we view<br />

art? the artist asks. How do we view ourselves? Do<br />

hidden assumptions about what art “is,” or what we<br />

“are,” prevent us from enjoying art or keep us from<br />

living comfortably with ourselves? These are the<br />

questions of the postmodern and of the post modern<br />

theatre.<br />

In theatre, which is a practical art, the notion of<br />

postmodernism can be understood concretely. Postmodern<br />

drama springs directly from the antirealistic<br />

theatre, but unlike most antirealistic theatre, it has<br />

little of the modernist’s aesthetic sense or social optimism.<br />

<strong>Where</strong>as the symbolists and surrealists worked<br />

to reveal higher orders of reality, and the Brecht ian<br />

epic theatre struggled to change the world and raise<br />

social expectations, the strict postmodernist does neither.<br />

The postmodernist abjures symbols (the postmodern<br />

is the art, one critic suggests, of the “missing<br />

metaphor”), and with no expectation of social progress,<br />

the postmodernist contemplates the future only<br />

warily if at all. Postmodern playwrights and directors<br />

are far more likely to explore the discontinuity of<br />

observable reality than they are to seek an integrated<br />

synthesis or “meaning” through theatrical works. Thus<br />

Aristotle’s “theme” often takes a beating in twentyfi<br />

rst-century theatre, where plays are likely to be held<br />

together not by an overarching central idea or message<br />

but by a mélange of ideas, images, and sensory<br />

discoveries.<br />

Postmodern art celebrates the apparent randomness<br />

of arbitrary juxtapositions. <strong>It</strong> prides itself not<br />

on logic and conviction but on delightful surprise<br />

and tantalizing (often bewildering) irrelevancies. Students<br />

of the postmodern fi nd its salient features in,<br />

for example, the largely improvised, haphazard, and<br />

disjunctive movements of break dancing, hip-hop,<br />

rapping, and DJ-ing. More conventional audiences<br />

experience it in the twenty-four-hour agglomeration<br />

of dramatic fragments, commercials, promos, newsbreaks,<br />

announcements, station identifi cations, and<br />

old fi lm clips that we see — often on split-screen —<br />

while remotely speed-surfi ng among a hundred-odd<br />

cable channels.<br />

The fi rst important postmodern theatre (although<br />

its creators refused to call it “theatre” and the term<br />

postmodern had yet to be coined) was the short-lived<br />

arts phenomenon called dada, which came to light at<br />

the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1916.<br />

As critic Mel Gordon describes it, dada was a “chaotic<br />

mix of balalaika music, [Karl] Wedekind poems, dance<br />

numbers, cabaret singing, recitations from Voltaire,

and shouting in a kaleidoscopic environment of paintings.”<br />

*So-called chance poetry, created by dada poet<br />

Tristan Tzara by pulling words out of a hat, led to cabaret<br />

performances of chance drama. The dadaists — as<br />

they came to be called (the name was chosen at random<br />

from an unabridged dictionary) — found themselves<br />

the artistic darlings of Berlin and Paris in the<br />

early 1920s. Though short-lived, dada clearly stimulated<br />

the experimentalism of the theatre of the absurd,<br />

which was its longer-lasting successor.<br />

<strong>Today</strong>’s theatrical postmodernism follows in the<br />

wake of French existentialism and the absurd. The<br />

late plays of Samuel Beckett best exemplify the pessimism<br />

and fl ight from meaning characteristic of these<br />

movements. Although Beckett explored meaninglessness<br />

in his earliest writings, by the 1980s his vision<br />

was grim if not completely nihilistic. In his short play<br />

Rockabye (1981), Beckett’s sole visible character is an<br />

old lady with “huge eyes in white expressionless face.”<br />

On a dark stage she rocks alone, dimly lit in a rocking<br />

chair; during the play she says but one word<br />

(“More”) in what is apparently a beyond-the-grave<br />

dialogue with her prerecorded voice. The play ends<br />

with the recorded voice saying:<br />

rock her off stop her eyes fuck life stop her eyes<br />

rock her off rock her off<br />

And the rocking stops as the lights fade out.<br />

Contemporary postmodernism also owes a debt<br />

to the other current of antirealistic theatre, the theatre<br />

of alienation as created and promoted by Bertolt<br />

Brecht. If Beckett’s theatre stimulates the postmodern’s<br />

intellectual pessimism, Brecht’s theatre stimulates its<br />

delight in stepping out of the dramatic situation — deconstructing<br />

drama into storytelling and disconnecting<br />

actors from characters in order to toss the play’s<br />

issues directly into the audience. Postmodern directors<br />

and dramatists infl uenced by Brecht therefore<br />

openly, even gaily, employ the theatre as an ironic<br />

metaphor, jumping back and forth between simulations<br />

of reality and comments on that very simulation.<br />

Many post-Brechtian and postmodern theatrical<br />

techniques stem from this discontinuity. Deliberate<br />

cross-gender casting — as, for example, actors switching<br />

roles as well as genders between the fi rst and second<br />

acts of Caryl Churchill’s Cloud Nine (1983), or a<br />

young actress with an obviously fake beard playing<br />

the old Jewish rabbi at the opening of Tony Kushner’s<br />

*Mel Gordon, Dada Performance (New York: PAJ Publications,<br />

1987), 313.<br />

Angels in America (1993) — forces us to confront a profound<br />

separation between the actor and his or her<br />

role. Sometimes even the audience does the separating,<br />

as in the 2001 off-Broadway production of Matthew<br />

von Waaden’s Eat the Runt, where the theatre<br />

spectators actually cast the eight roles — regardless of<br />

gender — from among the actors who presented themselves<br />

onstage before the play proper began.<br />

Increasingly, the raw mechanics of theatrical practice<br />

are — as Brecht instructed — evident today. For example,<br />

visible microphones, worn on the actor’s body,<br />

are increasingly employed in musicals and even some<br />

straight plays, forcing us to acknowledge the actor,<br />

and the theatrical technology the actor employs, beneath<br />

the character being played. Similarly, the sound<br />

mixer who adjusts volume levels is no longer hidden<br />

backstage but is plunked in the midst of the audience.<br />

In the postmodern theatre, the “showing” is part of<br />

the “show.”<br />

Plays increasingly comment on their own dramatization<br />

— their dramaturgy — as well. In The Producers<br />

(2001) a character asks another, “Why did you just<br />

walk downstage right?” In Urinetown (2001) a character<br />

asks another, “Is this where you tell the audience<br />

about the water shortage?” Other plays adopt<br />

the theatre or its repertory as their primary subjects.<br />

In one of the classic postmodern deconstructions of<br />

theatrical “reality,” the opening scene of Tom Stoppard’s<br />

The Real Thing (1982) is revealed to have been<br />

a staged play when, at the beginning of scene 2, we<br />

see the “characters” of scene 1 appear as the actors<br />

who played them. Shakespeare is fodder for many deconstructed<br />

variations: Amy Freed’s The Beard of Avon<br />

(2001) shows Shakespeare writing — or perhaps not<br />

writing — the plays attributed to him. Paul Rudnick’s<br />

I Hate Hamlet (1992) shows actors rehearsing and presenting<br />

a production of Hamlet. Both Lee Blessing’s<br />

1992 Fortinbras and Tom Stoppard’s seminal 1967 Rosencrantz<br />

and Guildenstern Are Dead expand on previously<br />

untold stories within the same play, and Athol<br />

Fugard’s Exits and Entrances (2004) centers on a delivery<br />

of Hamlet’s “To be or not to be?” soliloquy. Even<br />

Neil Simon’s Laughter on the 23rd Floor and musical<br />

stage version of The Goodbye Girl include scenes parodying<br />

performances of Shakespeare — Julius Caesar<br />

and Richard III, respectively. Shakespeare, however, is<br />

hardly the sole source of theatre-about-theatre, as<br />

witness the titles of Jeff Whitty’s Further Adventures of<br />

Hedda Gabler and Eric Michael Kochmer’s Chekhovian<br />

parody, Platonov! Platonov! Platonov! or The Case<br />

of a Very Angry Duck.<br />

What’s Happening? 257

And musicals of the postmodern era are almost<br />

all about show business, and usually about musicals.<br />

The Drowsy Chaperone, The Producers, George Gershwin<br />

Alone, A Class Act, The Boy from Oz, Urinetown, The<br />

Musical of Musicals — The Musical!, Curtain, and the<br />

regularly updated Forbidden Broadway are all twentyfi<br />

rst-century derivations, spin-offs, or parodies of Broadway<br />

musical traditions from earlier eras. <strong>It</strong> is certainly<br />

clear that twenty-fi rst-century postmodernist drama<br />

is delightedly cannibalizing — ingesting, chewing, and<br />

258 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

even tually regurgitating, in various ironic transformations<br />

— its past glories.<br />

� A Nonlinear <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

Aristotle said that plays should have a beginning,<br />

middle, and end, and they generally still do — but no<br />

longer always in that order. The conventional development<br />

of plot — from an inciting incident through<br />

intensifying action, climax, and denouement — is no<br />

Tom Stoppard’s The Invention of Love portrays various events in the life of the English classical scholar and poet A. E. Housman<br />

from age eighteen to seventy-seven, not only by jumping backward and forward in time but also through intriguing same-time<br />

conversations between the young Housman (played by Robert Sean Leonard, right) and Housman as a just-deceased old man<br />

(played by Richard Easton), here shown — along with their refl ections — sitting on a fallen antique monument (another postmodern<br />

touch) on the River Styx in Hades (the land of the dead). Both Leonard and Easton won Tony Awards for their Housman<br />

portrayals in the 2001 Broadway season. Sets and costumes are by Bob Crowley; lighting is by Brian MacDevitt.

longer uniformly presented in linear fashion. Temporary<br />

fl ashbacks, of course, have been used in drama,<br />

as well as in fi lm, for several decades. They appear<br />

prominently in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman,<br />

for example, and the action of Tennessee Williams’s<br />

The Glass Menagerie is, in effect, almost entirely a fl ashback.<br />

But in such linear works fl ashbacks are generally<br />

framed as such, as by a narrative or musical<br />

transition or, in fi lm, by a blurry cross-dissolve, which<br />

makes clear that the story is shifting to an earlier time<br />

period. In postmodern nonlinear drama, however,<br />

movement from one time zone to another is usually<br />

instantaneous and rarely narrated: the audience is<br />

simply expected to fi gure it out. Moreover, the audience<br />

is not necessarily “returned” to the present when<br />

a postmodern fl ashback concludes.<br />

A postmodern play proceeds in almost any order<br />

the playwright wishes to construct, and such timewarping<br />

no longer seems surprising. When Harold<br />

Pinter, in Betrayal (1978), organized his play’s nine<br />

scenes in mostly reverse chronological order, the decision<br />

was considered revolutionary and reviewers<br />

talked of little else. Two decades later, when David<br />

Auburn, in his 2001 Pulitzer Prize–winning Proof,<br />

began act 2 with a scene chronologically four years<br />

earlier than act 1 (requiring that a ghost appearing in<br />

act 1 be instantly seen — with no change of costume<br />

or makeup or explanation — as a living man in act 2),<br />

very few reviewers thought this reordering of events<br />

even worth mentioning. Indeed, the New York Times<br />

theatre critic called the play “as accessible and compelling<br />

as a detective story.” Postmodern plays are<br />

freed from the necessity to align themselves with a<br />

forward-moving arrow of time, and even from the<br />

need to explain when the arrow reverses direction.<br />

Here are a few other examples of postmodern nonlinear<br />

theatre:<br />

�<br />

�<br />

In Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize–winning 1993<br />

Angels in America, the action makes quantum<br />

moves in time — between previous centuries,<br />

the present, and the afterlife — with never so<br />

much as a program note, while actors jump back<br />

and forth between different roles and occasionally<br />

between different genders as well (also see<br />

the chapter titled “The Playwright”).<br />

In Tom Stoppard’s 1998 The Invention of Love, the<br />

principal character, poet and scholar A. E. Housman,<br />

is divided into a younger and an older self,<br />

each played by a different actor; the play’s scenes<br />

alternate back and forth between Housman’s stu-<br />

Jefferson Mays, as German transvestite Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, holds a<br />

treasured antique record player in Doug Wright’s multiple-award-winning<br />

I Am My Own Wife. Charlotte is one of thirty-three roles Mays plays in the<br />

show, which crosses gender, linguistic, and time barriers.<br />

�<br />

dent days, professorial years, and boat-borne journey<br />

to Purgatory after death. The younger and<br />

elder Housmans even cross paths for conversation<br />

as the eras of their lives intertwine.<br />

In Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife (2003), we<br />

continually swing forward and back through the<br />

life of the play’s main character, German transvestite<br />

Charlotte von Mahlsdorf. The play’s sole<br />

actor performs Charlotte not only in two genders<br />

but in two languages and at multiple ages — as<br />

well as playing playwright Wright (and thirtythree<br />

other characters) besides.<br />

None of these nonlinear — or gender or language or<br />

character — shifts represents dramaturgical novelty.<br />

Rather, each indicates a theatre — and an audience —<br />

prepared for instant cross-association and able to<br />

keep several ideas and chronologies in mind at the<br />

same time, melding them into a satisfying dramatic<br />

experience.<br />

What’s Happening? 259

� An Open <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

<strong>It</strong> is safe to say that, in the United States, theatre audiences<br />

and practitioners alike have opted for an “open”<br />

theatre — open, that is, for an infi nitely wider range<br />

of interests, cultures, and individuals than existed<br />

during any other period in theatre history. This openness<br />

— the word comes from Joseph Chaikin’s shortlived<br />

but extremely infl uential Open <strong>Theatre</strong> company<br />

of the American 1960s and 1970s — made us painfully<br />

conscious of the theatre’s challenge, after two<br />

world wars, to fully refl ect the humanity inside us<br />

and the society around us. For although Shakespeare<br />

(for instance) was certainly able to create magnifi cent<br />

female and ethnic characters (Beatrice and Cleopatra,<br />

Othello and Shylock) and his acting company was<br />

apparently skilled at bringing them vividly to life,<br />

the notion of an all-white (and all-male) theatre company<br />

claiming, in a speech of Hamlet’s, to hold “a<br />

mirror up to nature” has proven in the current age<br />

generally unsustainable. How can an exclusively male<br />

or an exclusively white — or even an exclusively singleethnicity<br />

company — wholly “mirror” the hopes and<br />

concerns of all human nature: women as well as men,<br />

gays and straights, Asians and blacks and Native Americans<br />

as well as whites?<br />

Postwar authors and directors, therefore, have increasingly<br />

sought to open the theatre to all comers.<br />

The postmodern disconnect between actor and character<br />

is helpful in creating this openness, as playwrights<br />

or directors seek to create “roles” more than<br />

characters, inviting the audience to see an actor not<br />

as a character but rather as an actor playing a character.<br />

So today a woman may play King Lear, a white<br />

actor may play a black Othello, and a black actor can<br />

The Propeller is an all-male acting company directed by Edward Hall; in this<br />

2006 production of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, Dugald Bruce<br />

Lockhart plays Petruchio (the tamer) and Simon Scardifi eld plays Katherine<br />

(the “shrew”). This is no mere novelty: as critic Ron Dungate aptly notes,<br />

“The Taming of the Shrew is OK as a play as long as you don’t take the violence<br />

against Kate seriously. But then you have to take it seriously — the play<br />

does. The play is seen to be what it is — a cruel play about making women do<br />

what you want by beating them up. The remarkable thing about this production<br />

is that the maleness of Propeller and its physical style enables the<br />

actors to fully confront this violence; we are more able to take the violence<br />

since we see Petruchio and Kate are both men and, crucially, the male Kate<br />

can give equal violence back. <strong>It</strong> doesn’t make it acceptable, it makes it<br />

possible to bear. The play becomes an intricate, multi-layered event and the<br />

message is truly disturbing.” The production, stirringly designed by Michael<br />

Pavelka, toured to London, New York, Perth (Australia), and Hong Kong after<br />

its Stratford-upon-Avon opening.<br />

260 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

play the English King Henry V, without at all compromising<br />

the integrity of the theatrical experience.<br />

Casting considerations have broadened to radically<br />

bend gender distinctions, cross racial lines, and span<br />

age ranges.<br />

Chaikin’s Open <strong>Theatre</strong> pioneered in this development<br />

for little more than a decade, combining social<br />

improvisation with Brechtian techniques, developing<br />

plays in which performers glided into and out of<br />

the characters they played (they also played scenery<br />

and props, and often played themselves), and using<br />

story and character merely as vehicles for direct interactions<br />

with audiences. These plays, which included<br />

Megan Terry’s Viet Rock, Susan Yankowitz’s Terminal,<br />

and the company-authored Mutation Show, were<br />

con tin ually evolving workshop performances that<br />

addressed immediate audience concerns. The Open<br />

<strong>Theatre</strong> toured Europe, as well as American campuses<br />

and prisons, making alliances with the New Lafayette<br />

<strong>Theatre</strong> in Harlem, El Teatro Campesino in California,<br />

and the Women’s Collective <strong>Theatre</strong>. Although it<br />

ended its existence in 1973, the Open’s infl uence lasts<br />

to this day, and its name may well stand to represent

the larger “opening” of our contemporary stage to<br />

the great diversity of our contemporary cultures, and<br />

to our diverse personal and sexual identifi cations and<br />

orientations.<br />

� A Diverse <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

From top to bottom, in gender, race, and ethnicity, in<br />

playwrights, performers, producers, and directors,<br />

American theatre is now broadly diverse.<br />

Women were practically unrepresented in the theatre<br />

until the seventeenth century (except in the commedia<br />

dell’arte and some medieval English pageant<br />

productions), and even afterward women were relegated<br />

mainly to acting, copying scripts, and building<br />

costumes. Now they are a major force at every level of<br />

the American theatrical arts. Since the 1980s, eight<br />

different women (Paula Vogel, Beth Henley, Marsha<br />

Norman, Wendy Wasserstein, Margaret Edson, Suzan-<br />

Lori Parks, Mary Zimmerman, Sarah Ruhl) have received<br />

Pulitzer Prizes or MacArthur “genius” grants<br />

for playwriting. Women directors, once a rarity, now<br />

represent at least one-third of the nation’s total fi eld<br />

and a comparable percentage of American producers<br />

and artistic directors as well. Meanwhile, feminist<br />

theatre ensembles — dozens of groups of women presenting<br />

plays by, about, and for women — have been<br />

founded throughout the United States. The goal of<br />

each is to present plays about gender-role stereotyping,<br />

abortion, pregnancy, motherhood, rape, the<br />

mother-daughter relationship, lesbianism, domestic<br />

violence, historically important women, battered<br />

women, and women in prison.<br />

Racial diversifi cation of American theatre shows<br />

similar development. Up to the mid-1950s, the American<br />

theatre was almost entirely written by, for, and<br />

about whites. Talented black writers were hardly ever<br />

able to secure productions, and even the best black<br />

actors usually were reduced to playing the roles of<br />

servants and occasional “exotics.” Then black-themed,<br />

black-authored, and black-acted drama began to surge<br />

forward in American culture.<br />

Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 A Raisin in the Sun, a realistic<br />

study of black family life, became the fi rst blackauthored<br />

play to appear on Broadway, and its director,<br />

Lloyd Richards, became Broadway’s fi rst black director.<br />

Not long after, a vigorous black theatre became a<br />

truly revolutionary force with the plays of African<br />

American Amiri Baraka. His Dutchman and The Toilet<br />

appeared off-Broadway in 1964 and confronted American<br />

racism with astonishing ferocity. Bakara (known<br />

as LeRoi Jones at that time) refused to shrink from his<br />

subject’s violent ramifi cations, and his gut-wrenching<br />

urban plays — set, respectively, in a subway car and a<br />

high school latrine — provided a startling wake-up<br />

call not only to American society but to the American<br />

stage. By 1965, Robert Hooks and Douglas Turner<br />

Ward, actors in the touring company of A Raisin in<br />

the Sun (Hooks also performed in Dutchman), had created<br />

the Negro Ensemble Company, bringing forth<br />

dramatist Lonne Elder III’s eloquent Ceremonies in Dark<br />

Old Men in 1969, and Charles Fuller’s 1981 A Soldier’s<br />

Play, about the murder of a black soldier in the American<br />

South, which received the Pulitzer Prize and paved<br />

the way for the emergence of August Wilson. Other<br />

noted African American playwrights continuing to<br />

produce in the current era are Ntozake Shange, whose<br />

for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the<br />

rainbow is enuf opened on Broadway in 1975 and has<br />

entered America’s dramatic repertory; the extraordinary<br />

August Wilson; director George C. Wolfe, whose<br />

Jelly’s Last Jam was a hit Broadway musical; and<br />

the very active Suzan-Lori Parks (Venus and Topdog/<br />

Underdog) and Lynn Nottage (Intimate Apparel), who<br />

are among America’s most-produced playwrights<br />

around the country at the time of writing (for more<br />

on Suzan-Lori Parks, see “The Playwright” chapter).<br />

The open theatre of today has been augmented<br />

with writers and theatre artists of all major ethnicities.<br />

Spanish-speaking theatre has existed in North<br />

America since the late sixteenth century, when Los<br />

Moros y Los Cristianos (The Moors and the Christians)<br />

was staged at the San Juan Pueblo near Santa Fe. In<br />

1965, the founding of El Teatro Campesino by Mexican<br />

American Luis Valdez created a homegrown Chicano<br />

theatre whose powerful creative and political<br />

thrusts electrifi ed California audiences and soon won<br />

national acclaim. Valdez’s Teatro was created with and<br />

for migrant farmworkers in rural California: “In a<br />

Mexican way,” wrote Valdez in 1966, “we have discovered<br />

what Brecht is all about. If you want unbourgeois<br />

theatre, fi nd unbourgeois people to do it.”*<br />

Noted Latina and Latino dramatists working today<br />

include Puerto Rican–born José Rivera (Marisol,<br />

1992), Chicano authors Josefi na López (Real Women<br />

Have Curves, 1990), Carlos Morton (The Miser of Mexico,<br />

1989), and Cuban-born Nilo Cruz, who received the<br />

2003 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for his enchanting Anna<br />

in the Tropics, portraying Cuban émigré workers in a<br />

*Quoted in Abel Franco, “Teatro Campesino: Change and<br />

Survival,” New World, 2 (Fall 1974), 22.<br />

What’s Happening? 261

Florida (Ybor City) cigar factory. Cruz’s version of Calderón’s<br />

Life Is a Dream premiered in California in 2007.<br />

Asian American theatre has claimed its share of<br />

the American theatrical scene as well, its quantum<br />

leap forward being David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfl y,<br />

which received both a Tony Award and a Pulitzer Prize<br />

during its 1988 Broadway premiere. Hwang’s play<br />

boldly reinterprets the Madame Butterfl y story, as well<br />

as its political and sexual prejudices, by incorporating<br />

both Western and Beijing opera techniques into a<br />

contemporary, highly postmodern play that explodes<br />

“Orientalist” stereotypes about Asians as viewed by<br />

Westerners. Hwang’s career continues to fl ourish (see<br />

the chapter titled “The Playwright”). Hwang wrote a<br />

new book for the 2002 Broadway revival of the Rodgers<br />

and Hammerstein musical The World of Suzie Wong,<br />

on Chinese immigration to the United States, and his<br />

Golden Child, on the same subject, was nominated for<br />

a best-play Tony Award. Hwang is only one of many<br />

Asian Americans now solidly ensconced in the American<br />

repertoire. Philip Kan Gotanda, Lonnie Carter,<br />

and Elizabeth Wong are among the others writing<br />

about relations between American and, respectively,<br />

Japanese, Filipino, and Chinese cultures.<br />

262 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

(Above) This Broadway revival of Lorraine Hansberry’s classic A Raisin in<br />

the Sun — directed by Kenny Leon and starring Sean Combs (left) as Walter<br />

Lee <strong>You</strong>nger, Audra McDonald as his wife, and Sanaa Lathan as his sister,<br />

Beneatha — attracted large crossover audiences on Broadway in 2004.<br />

(Top right) Many regional American theatres, including South Coast Repertory,<br />

present A Christmas Carol for Christmas audiences, but SCR also presents<br />

Octavio Solis’s La Posada Magica at the same time on their smaller<br />

stage. The play depicts a young Mexican girl joining her neighborhood<br />

posada, a reenactment of Joseph and Mary’s travel to Bethlehem. Tiffany<br />

Ellen Solano (left) plays the girl in this 2003 SCR production, directed by<br />

Solis, with Elsa Martinez and Mauricio Mendoza as Mary and Joseph.<br />

(Bottom right) “Fusion theatre,” which combines different performance<br />

traditions (usually Eastern and Western), is now widespread. Admired for its<br />

global, nonparochial perspective, it is sometimes criticized for appropriating<br />

the cultures from which it borrows. Shown here is a 2003 fusion production<br />

at New York’s Lincoln Center of Orphan of Zhao. Chen Shi-Zheng, a Chineseborn<br />

American, directed this twelfth-century Chinese tragic masterpiece<br />

in a free adaptation by noted American playwright David Greenspan. The<br />

music, composed by Stephin Merritt, featured both Chinese and Western<br />

instruments.

What’s Happening? 263

� A Global <strong>Theatre</strong> —<br />

and Macaronic Drama<br />

<strong>Today</strong>’s theatre is not only open and diverse but also<br />

global. Of course the theatre has been an international<br />

medium during most of its history. In ancient<br />

Greece, nearly all of the Hellenic city-states participated<br />

in the Great Dionysia, Athens’s springtime theatre<br />

festival, which also attracted traders and visitors<br />

from throughout the Mediterranean world. In Shakespeare’s<br />

time, plays — including his own — were set in<br />

<strong>It</strong>aly, France, Egypt, Bohemia, Greece, Austria, Denmark,<br />

Scotland, and other countries, including an island<br />

now thought to be Bermuda. Audiences for these<br />

plays included many foreigners, some of whom provide<br />

much of what we know about theatergoing in<br />

Shakespeare’s day.<br />

In subsequent centuries, theatre retreated to a more<br />

parochial insularity; then in the twenty-fi rst century<br />

it reemerged into an art form with a global profi le<br />

and an international audience. Several factors shaped<br />

this reemergence: the globalization of the world economy,<br />

the worldwide proliferation of art and culture<br />

through fi lm, television, and theatrical touring, the<br />

expansion of world tourism occasioned by substantially<br />

lower air fares in the jet age, and the worldwide<br />

social and economic upheavals and migrations during<br />

and after the cold war. For all of these reasons, it<br />

is nearly impossible to spend an hour on the sidewalks<br />

of any major city — New York, London, Tokyo,<br />

Toronto, Sydney — without hearing a broad mix of languages.<br />

And the theatre of today often refl ects both<br />

the multiple tongues and the international intellectual<br />

appetites of today’s globalized world.<br />

Critic Marvin Carlson uses the term macaronic —<br />

originally equating the mixture of Latin and early<br />

<strong>It</strong>alian spoken in medieval <strong>It</strong>aly to a maccarone (macaroni)<br />

of thrown-together pasta — to describe dramas<br />

that include speeches in different languages.* The<br />

European theatre has long been macaronic: even<br />

Shakespeare’s plays include many lines (and in two<br />

cases entire scenes) in French, <strong>It</strong>alian, Latin, or Welsh.<br />

More recent plays take this multilingualism much<br />

further. <strong>Can</strong>adian playwright David Fennario’s Balconville,<br />

about the relationship of French-speaking and<br />

English-speaking <strong>Can</strong>adians, is presented in both<br />

languages of offi cially bilingual <strong>Can</strong>ada. The French<br />

* Marvin Carlson, “The Macaronic Stage,” in East of West:<br />

Cross-Cultural Performance and the Staging of Differences, ed.<br />

Claire Sponsler and Xiaomei Chen (New York: Palgrave,<br />

2000), 15–31.<br />

264 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

comic play Les Aviateurs is performed entirely in English<br />

— the language of aviation — though it is a thoroughly<br />

French play that has (so far) been performed<br />

only in France. Endstation Amerika, Frank Castorf’s<br />

adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named<br />

Desire at the Berlin Volksbühne, was performed in German,<br />

French, and English. In the United States, Luis<br />

Valdez’s Zoot Suit and his subsequent I Don’t Have to<br />

Show <strong>You</strong> No Stinkin’ Badges, both about Chicano life<br />

in California, are written in Spanish and English.<br />

And nearly one-third of Lonnie Carter’s The Romance<br />

of Magno Rubio, as performed in California, is written<br />

in Tagalog (Filipino). Even more fl agrantly macaronic,<br />

however, is Homebody/Kabul (2004) by American playwright<br />

Tony Kushner, which is presented — usually<br />

with great vehemence — in French, Arabic, Pashto,<br />

Dari, English, and Esperanto.<br />

<strong>It</strong> is both realistic and poignant for the characters<br />

in these plays to speak in different languages. This<br />

linguistic variety conveys different states of emotion<br />

(Top right) Macaronic (multilingual) theatre reaches a high point in Ariane<br />

Mnouchkine’s production with her Théâtre de Soleil company production<br />

of Le Dernier Caravansérail (The Last Caravan), presented at the Lincoln<br />

Center Festival in New York in 2005. Mnouchkine and her company have<br />

been the greatest French theatre innovators over the past three decades,<br />

with Asian- or East Asian–inspired productions of plays by Shakespeare<br />

(Richard II, Twelfth Night), Aeschylus (the Oresteia), and Molière (Tartuffe),<br />

among others. Here she tackles an original subject — the global crisis of<br />

immigration — with a text developed from interviews she and her colleagues<br />

conducted all over the world. The six-hour production — portraying current<br />

immigrants from Afghanistan, Iraq, Kurdistan, and Iran crossing to Europe<br />

on the ancient Silk and Spice Roads — includes forty-two scenes, actors<br />

traveling by carts, boats, and other conveyances so that they never set foot<br />

on the ground, and a wide variety of languages totally unfamiliar to theatre<br />

audiences, even when they are heard above the screams and sounds coming<br />

from the stage. In this opening scene, “La Fleuve Cruel” (“The cruel river”),<br />

immigrants in a wicker basket are smuggled across violent and roaring<br />

“waves” created by a gigantic span of billowing fabric. The cacophony<br />

of multiple languages, together with the roar of the river and the screams<br />

of those thrown overboard, greatly intensifi es the realism of this global<br />

catastrophe.<br />

(Bottom right) Jean Verdun’s Tibi’s Law is a French play set in rural Africa;<br />

it premiered not in France but in the forty-four-seat “equity-waiver” Stages<br />

<strong>Theatre</strong> Center in Hollywood, California, in 2003, echoing the play’s theme<br />

of globalization and the third world by such a transnational opening. American<br />

slam poet Saul Williams plays the title role of an African “sayer” who<br />

offi ciates at the funerals of Africans killed by disease, poverty, and thoughtless<br />

police raids, while Erinn Anova plays his long-lost girlfriend, Mara. The<br />

audience is cast in the role of global tourists, sent to these funerals by<br />

travel agents so they may see, between safaris to the wild-game parks, the<br />

“real Africa.” The setting is by Grant Van Szevern, the lighting by Leigh Allen.

What’s Happening? 265

and different aspects of cultural identity — as well as<br />

the diffi culties inherent in intercultural communication<br />

— while still depending on Aristotelian basics of<br />

plot and character. And as many of us face the same<br />

challenges in our increasingly multicultural lives, the<br />

macaronic theatre mirrors our evolving nature.<br />

Macaronic theatre has begun to receive broad exposure<br />

and is learning to cope with the demands of<br />

multicultural dramatic speech. Casting directors are<br />

seeking bilingual performers. Playwrights and directors<br />

are learning to shape productions to make actions<br />

comprehensible without language clues. Actors<br />

are discovering how to heighten the transmission of<br />

meaning by gesture, tone of voice, and implication. <strong>It</strong><br />

is hard to overestimate the importance of this movement,<br />

which can depict confl icts between cultural survival<br />

and assimilation and give voice to the multiple<br />

perspectives of societies rent with factionalism and<br />

incipient terrorism.<br />

� A <strong>Theatre</strong> of Difference<br />

Gender, race, ethnicity, geography, and language are<br />

not the only sources of the new voices entering the<br />

theatre’s mainstream in the current era. Sexual preference<br />

has emerged as a defi ning issue for many<br />

theatre groups, theatre festivals, and theatre publications,<br />

each seeking to examine the political, cultural,<br />

and aesthetic implications of gay- and lesbian-themed<br />

drama. Sexual preference remained buried deeply in<br />

the closet during most of the theatre’s history. As recently<br />

as 1958 the representation of homosexuality<br />

was illegal in England and widely (though not legally)<br />

suppressed in America. The love that “dared not speak<br />

its name” came to the stage only through authors’ implications<br />

and audiences’ inferences. Gay playwrights,<br />

such as Oscar Wilde, Tennessee Williams, Gertrude<br />

Stein, Edward Albee, William Inge, and Gore Vidal,<br />

were forced to speak — at certain critical moments in<br />

their work — only by innuendo and through oblique<br />

code words.<br />

Dramatic changes occurred in the late 1960s, when<br />

gay and lesbian life and gay and lesbian issues began<br />

to be treated as serious dramatic subjects, most<br />

notably by Mart Crowley in his groundbreaking American<br />

comedy The Boys in the Band (1968). Since then,<br />

sexual-preference issues have become principal or secondary<br />

topics in hundreds of plays, including mainstream<br />

Broadway musicals (La Cage aux Folles, Falsettos,<br />

Kiss of the Spider Woman, The Wild Party, Avenue Q),<br />

popular comedies (Love! Valour! Compassion!, Jeffrey,<br />

The Little Dog Laughed), and serious dramas (Bent,<br />

266 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

M. Butterfl y, Gross Indecency, Breaking the Code, The<br />

Laramie Project, Take Me Out, I Am My Own Wife). Gay<br />

actors have come out of the closet (most of them<br />

theatrically) to advocate gay rights worldwide, as did<br />

the British classical star Ian McKellen in his one-man<br />

performance “A Knight Out” at the Gay Games in New<br />

York in 1994.<br />

In the wake of a new and terrible illness, a growing<br />

genre of AIDS plays (The Normal Heart, As Is) addressed<br />

the tragic human consequences of this disease, whose<br />

initial victims in the United States and Europe were<br />

predominantly gay. In 1992, Tony Kushner’s extraordinary<br />

Angels in America, subtitled “a gay fantasia on<br />

national themes,” proved the most celebrated American<br />

stage production of the decade.<br />

Differently-abled persons are also represented by<br />

new plays as well as by theatre companies that were<br />

Martin Sherman’s 1979 Bent received a Tony nomination for its harrowing<br />

tale of the treatment of German homosexuals during the rise of Adolf Hitler,<br />

and it paved the way for the serious — even tragic — theatrical treatment of<br />

homophobia. In this 2006 English revival at the Trafalgar Studios in London,<br />

Max (Alan Cumming, right) and Rudy (Kevin Trainor) are gay men imprisoned<br />

by the Nazis. Max pretends to be Jewish under the misapprehension that he<br />

will be treated less harshly. Costumes are by Mark Bouman.

Deaf West is a Los Angeles theatre for the hearing-impaired, and its production of the musical Big River, in which characters<br />

alternately speak, sing, and sign their roles, began on the company’s tiny home stage. From there it moved to the much larger<br />

Mark Taper Forum and then to Broadway, winning critical acclaim not merely for overcoming its “handicapped” label but for<br />

creating an altogether new theatre aesthetic of hearing and “seeing” musical drama at the same time. Tyrone Giordano (left)<br />

plays Huckleberry Finn, with Michael McElroy as Jim, at the American Airlines Theater in 2003.<br />

created specifi cally for these voices and for expanding<br />

differently-abled audiences. In New York, <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

by the Blind employs sightless actors for all of its productions.<br />

The National <strong>Theatre</strong> of the Deaf is one of<br />

several groups that create theatre by and for the hearing-impaired,<br />

employing American Sign Language<br />

(ASL) as their primary verbal dramatic medium. With<br />

Mark Medoff’s prize-winning Children of a Lesser God,<br />

the hearing-impaired reached a broad popular audience,<br />

and a number of hearing-impaired actors and<br />

actresses found national recognition.<br />

� Nontraditional Casting<br />

Across the country, color-blind or deliberately crosscolor<br />

casting — once thought of as daring — has become<br />

almost routine, particularly in the classics. As<br />

audiences more easily accept the notion that they are<br />

watching “performances of characters” rather than<br />

“characters” themselves, the theatre has increasingly<br />

cast African Americans in roles once thought to be<br />

reserved for whites, and, conversely, the white actor<br />

Patrick Stewart has played the black Othello (without<br />

makeup or changing any lines) opposite a black actress<br />

playing the white Desdemona.<br />

The New York Shakespeare Festival has been a leader<br />

in nontraditional casting, choosing Angela Bassett for<br />

Lady Macbeth, Morgan Freeman for Petruchio, and<br />

Denzel Washington for Richard III. In Los Angeles,<br />

meanwhile, the black actress Fran Bennett played King<br />

Lear, and in a state with less than 4 percent African<br />

Americans and Asian Americans combined, the Oregon<br />

Shakespeare Festival recruits and engages an acting<br />

company in which a full one-third of the members<br />

are non-Caucasian. Black, Asian, and Hispanic actors<br />

are often cast in American and European productions<br />

today in roles that represent, say, Elizabethan royalty,<br />

French aristocrats, Greek gods, or Judeo-Christian<br />

What’s Happening? 267

Kim Cattrall plays Claire in this 2005 London production of Brian Clark’s<br />

Whose Life Is <strong>It</strong> Anyway? — a play originally written to star a man as the<br />

paralyzed hospital patient who seeks to die. A revision to replace a man<br />

with a woman is hardly unprecedented (Neil Simon once rewrote his The<br />

Odd Couple so as to feature two women roommates instead of two men),<br />

but here TV star Cattrall (Sex and the City) brings added vulnerability to<br />

the character — as well as box-offi ce power to the production (as did Mary<br />

Tyler Moore when she played the role on Broadway). Acting remains the only<br />

profession that permits gender discrimination in hiring, because the perceived<br />

gender of a character is often a crucial part of the play. The choice<br />

of gender, however, may provide advantages in either direction. Alexander<br />

Siddig plays the doctor; Peter Hall directed.<br />

Bible fi gures, thus dispensing fully with stereotypes<br />

of received images.<br />

Cross-gender casting is also commonplace in the<br />

postmodern age, as in the case of Bennett’s King Lear<br />

or, at London’s Globe <strong>Theatre</strong>, Mark Rylance’s Cleopatra<br />

and Olivia. The New York Shakespeare Festival<br />

has also proved a pioneer in this area, featuring<br />

New York’s fi rst female Hamlet in modern times. By<br />

now, female Hamlets, Prosperos, Richard IIs, and Rich-<br />

268 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

ard IIIs are everywhere apparent — as are male Rosalinds<br />

and Lady Bracknells. And in Bridge and Tunnel<br />

on Broadway in 2006, the black, Baltimore-born actress<br />

Sarah Jones played fourteen different roles — male and<br />

female, black and white, Pakistani, Lithuanian, Mexican,<br />

Russian, Jamaican, Jordanian, Chinese, and African<br />

American — all with uncanny accuracy, charm,<br />

and respectful admiration of the shared problems<br />

and challenges of immigration and assimilation, the<br />

“bridges and tunnels,” that affect a great majority of<br />

our current national corpus.<br />

Yet other individual movements in theatre, while<br />

not as widespread as those described above, have created<br />

new theatrical styles, or modes, with increasing<br />

popularity in the twenty-fi rst century.<br />

� Spectacular <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

Aristotle considered spectacle one of the six components<br />

of theatre, but the past decades have seen theatre<br />

move from mere spectacle (that which is seen) to<br />

the totally spectacular (that which astounds). In part,<br />

this shift refl ects the development of new technologies,<br />

affecting both visual and sound design; and in<br />

part, it refl ects the emergence of a new arts aesthetic.<br />

Some of the new theatre technology (see the<br />

chapter titled “Designers and Technicians”) comes<br />

from cinema, with its dazzling computer graphics,<br />

ani mations, and digitized motion-capture, and from<br />

the contemporary circus. The effects to be seen in<br />

fi lms like Star Wars and Lord of the Rings, and in Cirque<br />

du Soleil productions like O and Kà, have encouraged<br />

stage directors and designers to discover computerized<br />

technologies that in a matter of nanoseconds<br />

can create and remove lakes and replace them with<br />

tall buildings or vast cauldrons of hellfi re, can move<br />

lights and change their colors second by second, and<br />

can produce seemingly magical illusions and even<br />

upend whole stages, plunging the actors into the unknown<br />

below. And the pop/rock concert stage has created<br />

sound systems capable of reaching ear-blasting<br />

volume while still maintaining clarity of tone and<br />

mellowness of timbre, reaching every seat in the house<br />

simultaneously and in the process overthrowing, as it<br />

were, the very speed of physical sound.<br />

Such spectacular effects reach their apex in the<br />

high-budget (and high-ticket) Broadway musicals, with<br />

their falling chandeliers and descending helicopters,<br />

or in Cirque du Soleil extravaganzas with their<br />

gyrating stages and loudspeakers fi tted behind every<br />

seat in the audience. But audiences have come to ex-

pect these effects in such shows — pricey as they are —<br />

to the extent that audiences for Broadway musicals<br />

willingly accept that the “characters” whose lives and<br />

fortunes they’re presumably following have visible<br />

microphones pasted on their foreheads (or, on the<br />

naked actors in Stephen Sondheim’s Passion, wires running<br />

down their backs), in return for the amplifi ed<br />

and digitally processed sound they enjoy in return.<br />

There is also an aesthetic behind the theatre’s current<br />

turn from spectacle to spectacular. The French<br />

theorist Antonin Artaud argued fi ercely in the 1930s<br />

that theatre should have “no more masterpieces,” that<br />

words in dramas should be valued more for their vibrations<br />

than for their meanings and have only the<br />

importance they have in dreams. Artaud’s proposed<br />

theatre was one of overwhelming sounds and visual<br />

images that would dominate the stage. His arguments,<br />

not fully tested in his own time, have proven greatly<br />

infl uential in ours, starting with the unscripted happenings<br />

of the 1960s and the more lasting performance art<br />

that followed in the 1980s and continues to this day.<br />

Performance art is not normally spectacular in the<br />

technological sense. <strong>It</strong> is, however, intensely visual<br />

and generally unconcerned with dramatic matters of<br />

plot structure, logical argument, or character development<br />

— preferring instead explosive, arresting, shocking,<br />

provocative, or hilarious imagery. Such art tends<br />

by its nature to be transitory; its individual performances<br />

are often brief (fi fteen minutes, say), attended<br />

by small audiences, and not usually meant to be repeatable<br />

other than for occasional short runs. Most<br />

performance artists prefer it this way. But several have<br />

moved into the more rigorous demands of full theatrical<br />

presentation, often in national or international<br />

tours. Laurie Anderson, one of the most noted such<br />

artists today, pushes the envelope with advanced visual<br />

and sound technologies and with elements of<br />

the conventionally dramatic: she has performed her<br />

Moby Dick, after Melville’s novel, around the world.<br />

Karen Finley’s best-known solo performances have<br />

a strong political thrust. One piece, in which Finley<br />

smeared her naked body with chocolate to represent<br />

the exploitation and sexual abasement of women, led<br />

the National Endowment for the Arts to revoke the<br />

artist’s funding, and so, for her subsequent Shut Up<br />

and Love Me, Finley again smeared herself with chocolate,<br />

this time inviting audience members to lick<br />

it — at twenty dollars a lick, to compensate for the loss<br />

of her NEA grant. By confronting viewers with their<br />

own lust — and disgust — Finley creates a vividly memorable<br />

unease.<br />

Laurie Anderson is a long-recognized performance artist, specializing in<br />

the integration of visual excitement and electronic sound perturbations. In<br />

her “techno-opera” of Moby Dick, as presented at the Brooklyn Academy<br />

of Music in 1999, Anderson serves as singer, speaker (in many voices),<br />

composer, violinist, keyboardist, guitarist, and operator of an electronic,<br />

sound-generating Talking Stick, mostly while perched on a supersized chair<br />

of her own invention.<br />

� Verbatim <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

<strong>Theatre</strong> has always dealt with current politics. Indeed,<br />

the potentially short lead time between initial conception<br />

and fi nished product is one of the advantages<br />

live theatre has over fi lm. But the twenty-fi rst century<br />

has seen a virtual explosion of up-to-the-minute<br />

dramas performed on major stages, particularly in<br />

England and America. Many of these may be called<br />

“verbatim theatre,” as they have been developed from<br />

transcripts of real-life speeches and interviews. Here<br />

are a few examples:<br />

�<br />

My Name is Rachel Corrie was compiled from the<br />

diaries and e-mail messages of American peace<br />

What’s Happening? 269

(Top) Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen’s The<br />

Exonerated, directed by Bob Balaban<br />

and presented at the Culture Project<br />

in New York and at Riverside Studios<br />

in London (shown here), is a verbatim<br />

drama based on interviews with actual<br />

death-row prisoners sentenced for<br />

crimes they were later found not to have<br />

committed. The play basically asks:<br />

How many others were executed before<br />

their verdicts could be reexamined and<br />

overturned? By openly reading the visible<br />

interview transcripts, the actors emphasize<br />

the real-life authenticity of their<br />

roles, as well as the equally real death<br />

that the “authors” of the transcripts just<br />

barely avoided.<br />

(Bottom) Tony Kushner, Harold Pinter,<br />

and Vanessa Redgrave were among those<br />

angrily protesting the cancellation of<br />

the 2006 New York <strong>Theatre</strong> Workshop<br />

production of My Name Is Rachel Corrie,<br />

and the public fury led to the verbatim<br />

script’s eventual New York presentation<br />

the following year. Here, Megan Dodds<br />

reprises her London role for the Minetta<br />

<strong>Theatre</strong> production. Alan Rickman,<br />

who had transcribed the script from<br />

Corrie’s diary entries and e-mail journals,<br />

directed.<br />

activist Corrie, who died in Gaza in 2003 while<br />

trying to stop an Israeli bulldozer from demolishing<br />

a Palestinian home. Despite its success at London’s<br />

Royal Court <strong>Theatre</strong> in 2005, its scheduled<br />

New York opening was “postponed” (in effect<br />

canceled) the following year in deference to reactions<br />

from persons opposed to the play’s theme.<br />

A resulting furor in the English and American<br />

theatre communities, however, led to the play’s<br />

270 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

�<br />

subsequent mounting later that season at a different<br />

off-Broadway theatre.<br />

Robin Soams’s Talking to Terrorists, a transcription<br />

of interviews with persons involved in terrorism<br />

and torture around the world, also premiered at<br />

London’s Royal Court in 2005. The play’s graphic<br />

accounts of torture are recounted in the words<br />

of torturers and their victims alike. The play<br />

has since been produced in Boston and Tehran.

�<br />

Soams’s equally verbatim Arab-Israeli Cookbook<br />

has run successfully in London, Los Angeles, and<br />

Toronto.<br />

Stuff Happens, by celebrated British playwright<br />

David Hare, deals with the creation of the British-<br />

American coalition during the buildup to the<br />

Iraq War; the play’s title comes from U.S. Defense<br />

Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s response, during a<br />

�<br />

(Top) Talking to Terrorists, produced by England’s Out of Joint<br />

company, is a verbatim text compiled by Robin Soams entirely<br />

from interviews of ex-terrorists — or “freedom fi ghters” as they<br />

call themselves — and their victims. This “living journalism,” as<br />

it is sometimes called, aims for a comprehensive but not overly<br />

polemical representation of the many aspects of political protest<br />

when taken to extreme violence. When the play ends with the<br />

cast singing “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” there is some hope that<br />

a comprehensive look might someday lead to a comprehensive<br />

solution rather than a narrow, one-sided victory. Such, indeed, is<br />

the deepest goal of theatre in every generation since the ancient<br />

Greeks. Max Stafford-Clark, who heads Out of Joint and specializes<br />

in verbatim theatre, directed; Chipo Chung (speaking, in foreground)<br />

is one of the eight-member acting ensemble who play<br />

the work’s many roles.<br />

(Bottom) David Hare’s Stuff Happens, its title based on an<br />

offhand comment by U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld<br />

explaining why things go wrong in wartime, was the English<br />

dramatist’s reenactment of discussions between the U.S. and<br />

British governments during the early days of the Iraq War. George<br />

W. Bush and Tony Blair are among the play’s major characters.<br />

Some of the text was taken from verbatim records, some was<br />

speculative deduction, and some, the author acknowledged, was<br />

“pure guesswork.” Despite the widely held expectation that the<br />

play would simply condemn the invasion of Iraq, a position Hare<br />

was understood to uphold, the play — true to the demands of<br />

dramaturgy — presented both sides of the issue with reasonably<br />

persuasive authority, making for taut drama. In this 2004 premiere<br />

at the National <strong>Theatre</strong>, Alex Jennings (seated, foreground)<br />

plays President Bush, backed by (from left to right) Adjoa Andoh<br />

as U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Dermot Crowley as<br />

Rumsfeld, and Desmond Barrit as Vice President Richard Cheney.<br />

Across the stage, Nicholas Farrell (on the telephone) is Prime<br />

Minister Blair. The director was Nicholas Hytner, and the set was<br />

designed by Christopher Oram.<br />

press conference, to the looting of Baghdad. <strong>It</strong> has<br />

played widely in England and America since its<br />

2004 London premiere.<br />

Embedded, created by actor Tim Robbins for the<br />

Los Angeles Actors’ Gang in 2003, portrays a U.S.<br />

attack on the fi ctional country of “Gomorrah,”<br />

where the military embeds reporters with the<br />

advancing forces and pressures them to cover<br />

What’s Happening? 271

Manifest Destiny—labeled an “opera from Hell “ — is set variously<br />

in a Middle East terrorist training camp, a London fl at, and the<br />

Guantánamo Bay prison. This dangerous work created powerful<br />

representations of suicide bombers and the war on terror at<br />

the 2005 Edinburgh (Scotland) Fringe Festival, provoking both<br />

excitement and criticism, as was intended. “Opera” here should<br />

be understood in its original meaning — “work” — for although the<br />

ninety-minute piece was sung-through (the contemporary music is<br />

by Keith Burnstein, with a libretto by the strongly political Welsh<br />

playwright Dic Edwards), the presentation bore little relation<br />

to what is normally seen in an opera house, and the political<br />

issues were graphically and brutally presented. Some of the most<br />

graphic scenes actually anticipated actions that were yet to be<br />

made public, including the rise of female suicide bombers and<br />

incidents of prisoner torture. David Wybrow directed.<br />

�<br />

U.S. actions favorably while suppressing reports of<br />

casualties. The half-masked characters clearly are<br />

meant to be seen as America’s government leaders<br />

of that time.<br />

Sin, a Cardinal Deposed was created by playwright<br />

Michael Murphy from a thousand pages of the<br />

Boston archdiocese’s Cardinal Law’s court deposition,<br />

plus letters and public documents from<br />

priests, doctors, and sexual-abuse victims. The<br />

verbatim script was performed by six actors of<br />

the Bailiwick <strong>Theatre</strong> in Chicago in 2004 to<br />

great — and often tearful — acclaim.<br />

In addition to those new plays of immediate political<br />

pertinence, the current theatre is home to new<br />

stagings of classic dramas, particularly Greek tragedies,<br />

that are openly refl ective of current world crises.<br />

Such productions included Kate Whoriskey’s<br />

Antigone at South Coast Repertory in California,<br />

Katie Mitchell’s Iphigenia at Aulis at the National<br />

<strong>Theatre</strong> of England, and Tony Harrison’s Hecuba for<br />

the Royal Shakespeare Company. All of these productions<br />

have drawn direct parallels between the<br />

wars of the ancient Greeks and those of our own era.<br />

Hecuba, for example (which starred Vanessa Redgrave<br />

and played engagements in London, New York,<br />

and Washington, D.C. in 2005), was set in a modern,<br />

Middle Eastern refugee camp run by an allpowerful<br />

“coa lition force” that had been organized<br />

against Trojan “terrorists.”<br />

272 Chapter 11 | <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Today</strong><br />

� Dangerous <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

Besides being politically immediate, late modern and<br />

postmodern theatre has increasingly been seen as dangerous.<br />

The nudity and sensory assault of much contemporary<br />

drama have caused consternation to some.<br />

Subjects such as political torture (Death and the Maiden),<br />

the Nazi Holocaust (Ghetto, The Deputy), prison atrocities<br />

(Bent, The Island), and urban mayhem (Aven “U”<br />

Boys) have also proliferated in today’s theatre. Simulated<br />

homosexual intercourse in Angels in America<br />

resulted in banning the play in many communities;<br />

vulgar language in David Mamet’s 1983 Glengarry Glen<br />

Ross (“Fuck marshalling the leads. What the fuck talk is<br />

that?”), for example, and the very title of Mark Ravenhill’s<br />

Shopping and Fucking have occasioned barrages<br />

of angry letters to theatre producers and newspaper<br />

editorial pages. Accusations of religious defamation<br />

led to bomb threats at the 1998 New York opening of<br />

Terrence McNally’s Corpus Christi, which concerns a<br />

Jesus-like character who has sexual relations with his<br />

disciples; legal threats put forth by members of the<br />

Indiana legislature prevented Purdue University from<br />

producing the same play. And Neil LaBute’s violent,<br />

baby-murdering The Distance from Here was met with<br />

outrage by some subscribers and loud screams from at<br />

least one audience (as well as plaudits from many critics)<br />

at its 2004 U.S. premiere at the Manhattan <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

Club. The theatre continually treads on toes — and<br />

sometimes the toes kick back.

(Above) The director of Howard Brenton’s Romans in Britain was hauled<br />

into Old Bailey — the venerable British court — when the play fi rst opened at<br />

England’s National <strong>Theatre</strong> in 1980. He was accused of creating an act of<br />

“gross indecency” when actors simulated the rape of a naked Celt male by<br />

a naked Roman soldier during the Roman occupation — two thousand years<br />

previously. The director (Michael Bogdanov) won his case, but Brenton’s<br />

powerful play, which draws parallels with modern-day English rule in Northern<br />

Ireland, still sparks furious controversy. This Sheffi eld, England, revival<br />

in 2006, with its luxuriously verdant setting by Ralph Koltai, may suggest<br />

an even deeper parallel that the author did not consider: the rape of the<br />

natural planet by civilization. Samuel West directed.<br />