Black Soldiers in Tuscany during World War II

Black Soldiers in Tuscany during World War II - Darby Military ...

Black Soldiers in Tuscany during World War II - Darby Military ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

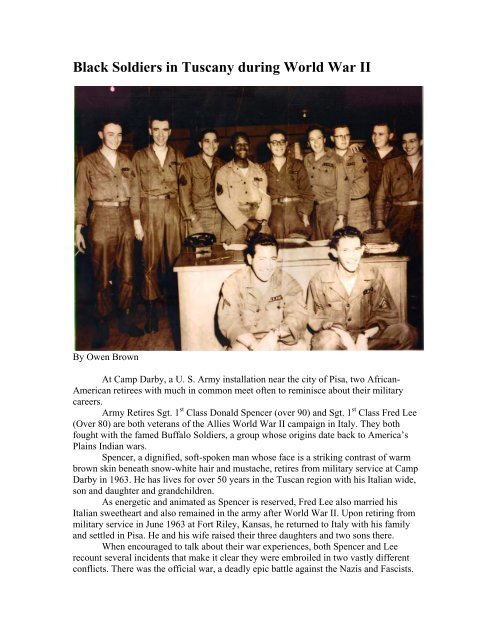

<strong>Black</strong> <strong>Soldiers</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tuscany</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>II</strong>By Owen BrownAt Camp Darby, a U. S. Army <strong>in</strong>stallation near the city of Pisa, two African-American retirees with much <strong>in</strong> common meet often to rem<strong>in</strong>isce about their militarycareers.Army Retires Sgt. 1 st Class Donald Spencer (over 90) and Sgt. 1 st Class Fred Lee(Over 80) are both veterans of the Allies <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>II</strong> campaign <strong>in</strong> Italy. They bothfought with the famed Buffalo <strong>Soldiers</strong>, a group whose orig<strong>in</strong>s date back to America’sPla<strong>in</strong>s Indian wars.Spencer, a dignified, soft-spoken man whose face is a strik<strong>in</strong>g contrast of warmbrown sk<strong>in</strong> beneath snow-white hair and mustache, retires from military service at CampDarby <strong>in</strong> 1963. He has lives for over 50 years <strong>in</strong> the Tuscan region with his Italian wide,son and daughter and grandchildren.As energetic and animated as Spencer is reserved, Fred Lee also married hisItalian sweetheart and also rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the army after <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>II</strong>. Upon retir<strong>in</strong>g frommilitary service <strong>in</strong> June 1963 at Fort Riley, Kansas, he returned to Italy with his familyand settled <strong>in</strong> Pisa. He and his wife raised their three daughters and two sons there.When encouraged to talk about their war experiences, both Spencer and Leerecount several <strong>in</strong>cidents that make it clear they were embroiled <strong>in</strong> two vastly differentconflicts. There was the official war, a deadly epic battle aga<strong>in</strong>st the Nazis and Fascists.

And there was the “unofficial war”, a demoraliz<strong>in</strong>g, daily struggle to survive the antiblackclimate <strong>in</strong> camps near the battlefront.Both men spoke candidly about the bias they encountered <strong>in</strong> the camp – theracially offensive comments and treatment that seemed designed to underm<strong>in</strong>e theirconfidence.“The black soldier was not supposed to be a fighter,” expla<strong>in</strong>ed Lee, describ<strong>in</strong>gthe prevail<strong>in</strong>g attitude of army brass.“We had some trash!” he <strong>in</strong>sisted. “Just like the whites had some trash!”In spite of hav<strong>in</strong>g to contend with enemies on and off the battlefield, the two menalso recalled <strong>in</strong>cidents that reflect the bittersweet, even comical side of their warexperiences. Interspersed with memories of racially discrim<strong>in</strong>atory practices are antidotesthat lend a human dimension to the war and its aftermath.Spencer, for example, enjoys rem<strong>in</strong>isc<strong>in</strong>g about an annual ritual that onceengaged two <strong>in</strong>tractable foes – American officials at Camp Darby and an aggrievedItalian family.“In the period follow<strong>in</strong>g the Allied victory over the Axis powers, an Italian familywould show up once a year at the Camp Darby headquarters to present a legal-look<strong>in</strong>gdocument to the base authorities which denounced the Americans for trespass<strong>in</strong>g onprivately-owned property,” said Spencer. “The family members <strong>in</strong>sisted that they ownedthe land on which Camp Darby was located.”“They had purchased the property, they claimed, from an American militaryofficer. A <strong>Black</strong>-American military officer,” said Spencer, gr<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g.From Laborer to Soldier-TranslatorBuffalo Soldier Donald Spencer was born on June 29, 1910, <strong>in</strong> Thelma, NorthCarol<strong>in</strong>a, but was reared <strong>in</strong> New York City’s Harlem District. Caught up <strong>in</strong> the fervor ofthe forties, he enlisted <strong>in</strong> the Army.It was the summer of 1942, and he was 32 years old. After several months of<strong>in</strong>tensive combat tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g at Fort Dix, New Jersey, he was then assigned with the 99 thInfantry Division.In November 1942, Private Spenser’s division departed for North Africa, arriv<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> the city of Casablanca on Nov. 18. There, the 99 th would soon dace the comb<strong>in</strong>edGerman-Italian forces. Though he served as a laborer, not as a combat soldier, Spencerrepeatedly jo<strong>in</strong>ted the fight<strong>in</strong>g forces.For his battlefield performance dur<strong>in</strong>g the Tunisian Campaign, he was awarded aBronze Arrowhead and a Bronze Star – one of five Bronze Stars he would eventuallyreceive dur<strong>in</strong>g the war.Spencer sometimes falters when try<strong>in</strong>g to recall the details of the battles <strong>in</strong> whichhe fought; campaigns waged <strong>in</strong> North Africa, Southern Italy and <strong>Tuscany</strong>. As a youngfather, though, he often talked to his son Paul, now a mechanical eng<strong>in</strong>eer, about hisbattlefield experiences n Africa and Italy.“It wasn’t difficult for me to talk to him about the war,” he offers. “Sometimes I’dtell him, sometimes I wouldn’t.”But there were also times when the former Buffalo Soldier, traumatized by warexperiences, would simply tell his son, “You don’t want to know.”

Follow<strong>in</strong>g the Tunisian campaigns <strong>in</strong> North Africa, Spencer’s division left forItaly, arriv<strong>in</strong>g at Paestum <strong>in</strong> September 1943. his divisions miss<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> Italy was toparticipate <strong>in</strong> the Allied struggle to destroy the Gothic L<strong>in</strong>e, the defenses that theentrentched German occupy<strong>in</strong>g force had constructed to bar the Allies from the PoValley, a rich agricultural and <strong>in</strong>dustrial center <strong>in</strong> the north of Italy.Once <strong>in</strong> Italy, the 99 th jo<strong>in</strong>ed other re<strong>in</strong>forcement units selected to augment the92 nd division, the famous military group known as the Buffalo <strong>Soldiers</strong>. At the time, the92 nd was engaged <strong>in</strong> pierce, protracted fight<strong>in</strong>g along the coastal sector of the LigurianSea and, to the east <strong>in</strong> Massa and <strong>in</strong> such Serchio Valley mounta<strong>in</strong> towns as Pietrosantaand Castelnuovo di Garfagnana.Besides work<strong>in</strong>g as a laborer and fight<strong>in</strong>g on the battlefield, Spencer also servedas a sussistenza, a position that required him to translate English <strong>in</strong>to Italian for Italianmilitary officials and to translate Italian <strong>in</strong>to English for American Army officials.Though untutored <strong>in</strong> Italian, he possessed a natural facility with the language, and isexceed<strong>in</strong>gly proud, to this day, of the contributions he made as an <strong>in</strong>terpreter.Spencer values, as well, several less dramatic, but equally importantcontributions—dispens<strong>in</strong>g food to children <strong>in</strong> the war-torn areas and mak<strong>in</strong>g sure theyreceive prompt medical attention; and comfort<strong>in</strong>g the wounded German prisoners <strong>in</strong> hiscare while help<strong>in</strong>g them onto Allied ships at the port of Livorno, <strong>in</strong> the Tuscan region.With his deliberate speech and calm demeanor, Spenser often sounds as id he hasmanaged to distance himself from the emotional turmoil that the wartime racial climategenerated.“<strong>Black</strong> soldiers,” he recalls dryly “lived <strong>in</strong> tents while the white soldiers lived <strong>in</strong>build<strong>in</strong>gs that were located along the lush shorel<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> Tirrenia, a seaside resort near thebase.”“After military authorities decided to move the Camp Darby’s black soldiers <strong>in</strong>tothe build<strong>in</strong>g, the white soldiers retaliated,” said Spencer. “They tour out all the plumb<strong>in</strong>gwhen they heard the black soldiers were go<strong>in</strong>g to move <strong>in</strong>.”After the war, the humiliations cont<strong>in</strong>ued.“White servicemen were allowed to perform normal, peacetime military duties,”contends Spencer, “while black soldiers were assigned to such menial tasks as garden<strong>in</strong>gand ma<strong>in</strong>tenance work around the homes of officers.”And when the soft-spoken Buffalo Soldier applied <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g for permission tomarry his Italian sweetheart, his commander ignored the request.Says the amazed, elderly war veteran, “They were throw<strong>in</strong>g the application papers<strong>in</strong>to the trash can!”But the <strong>in</strong>cident that still mystifies him after more then 50 years is the promotionhe earned , but never received, He was promoted to E-7 while serv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Italy, claimsSpencer. Yet he has never received the recognition or monetary value for the promotion,which dates back to 1945.In spite of the years wasted try<strong>in</strong>g to resolve the matter, Donald Spenser faces lifewith equanimity. When describ<strong>in</strong>g the affront, he manages to sound more like a bemusedobserver then a frustrated veteran.“I guess they’re wait<strong>in</strong>g for me to die.” He suggests, without the slightest trace ofrancor.

Still Await<strong>in</strong>g RecognitionLike his friend and fellow veteran Donald Spencer, Fred Lee is equally proud ofhis wartime military record. He was one of the few black-American, non-commissionedofficers to see combat dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>II</strong>.Lee was born on Dec. 19, 1918 <strong>in</strong> Birm<strong>in</strong>gham, Ala., but spent his childhoodyears <strong>in</strong> Akron, Ohio, where he attended <strong>in</strong>tegrated public schools. In March 1941, soonafter be<strong>in</strong>g drafted <strong>in</strong>to the army, he was sent to Fort Bragg, N.C. for basic tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.Follow<strong>in</strong>g months of <strong>in</strong>tensive tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, Lee was assigned to the 184 th FieldArtillery Battalion, Fort Lee, Va. After tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with the 96 th Tank Division <strong>in</strong> FortCuster, Mich., he jo<strong>in</strong>ed the all-black 92 nd Infantry Division <strong>in</strong> Fort Huachuca, Ariz., fordeployment with a convoy to the Mediterranean.In the summer of 1943, Lee arrived <strong>in</strong> Italy, land<strong>in</strong>g, he recalls, soon after theNazis and their Fascist allies had moved on up above the Tuscan towns of Viareggio andLucca. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the Allied campaign <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tuscany</strong> and other regions, his division foughtcostly battles <strong>in</strong> several areas near the cities of Florence, Genoa, Milan, <strong>in</strong> the seasidetowns of Forti di Marmi, La Spezia and Massa and <strong>in</strong> the villages of Pietrasanta andLucca and others to the north and northeast.As the Allied casualties mounted, the need for more troops <strong>in</strong>creased. Lee’sdivision, the 92 nd , would undergo several dramatic changes. Its numbers would swell tonearly 25,000 troops, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g personnel not only for <strong>in</strong>fantry, but for medium and lightartillery, tanks and tank destroyers. More significantly though, the division would be<strong>in</strong>tegrated racially. White re<strong>in</strong>forcements arrived from Brita<strong>in</strong> and the U.S., along withsecond-generation Japanese-American troops or Nisei.The Asian, black and white soldiers were expected to work together towards acommon goal, yet the old racial prohibitions rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>tact.

“The black soldier,” Lee recalls, “was the last to get anyth<strong>in</strong>g – whether it wasclothes, sheets, pillows or pillowcases.”He recalls, as well, the more demoraliz<strong>in</strong>g practices: deny<strong>in</strong>g African-Americansoldiers a chance to engage <strong>in</strong> combat; restrict<strong>in</strong>g them to janitorial work and jobs <strong>in</strong> themess hall; and hous<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>in</strong> segregated, less-desirable liv<strong>in</strong>g quarters.Los<strong>in</strong>g the paperwork for promotions or major career advancement was anothertactic used to demoralize the black soldier. For his wartime efforts, Lee was awarded theEuropean Campaign Medal with two battle stars as well as the <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>II</strong> VictoryMedal and the <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>II</strong> Occupational Medal. While earn<strong>in</strong>g these awards on thebattlefield, he decided to apply for officers’ candidacy school. Unfortunately, hisapplication papers disappeared. To this day, Lee is conv<strong>in</strong>ced that his superiors either lostor trashed his application.Lee adds that the military’s discrim<strong>in</strong>atory practices at the time also extended toaffairs of the heart. To discourage African-American soldiers from fraterniz<strong>in</strong>g with theItalian women, army brass would rout<strong>in</strong>ely give an African-American soldier extra dutyor cancel his leave pass, thus prevent<strong>in</strong>g him from go<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to town to see his girlfriend.“These types of <strong>in</strong>equities enraged the black soldiers at Camp Darby,” says Lee.Troubled by the mount<strong>in</strong>g racial tensions, the army called <strong>in</strong> the celebrated blackarmy officer, Brig. Gen. Benjam<strong>in</strong> Davis, Sr., to help calm the troops. Davis had enlisted<strong>in</strong> the army dur<strong>in</strong>g the Spanish-American <strong>War</strong> and had served dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> I withthe 99 th Regiment, an all-black cavalry unit. Years later, he was appo<strong>in</strong>ted as specialadvisor to General Dwight Eisenhower and was assigned to the politically sensitivemission of <strong>in</strong>spect<strong>in</strong>g the army’s black troops and aid<strong>in</strong>g their progress.Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>II</strong>, Davis traveled around to the various bases and camps,review<strong>in</strong>g the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs for black recruits, suggest<strong>in</strong>g policies to improve theirliv<strong>in</strong>g conditions and try<strong>in</strong>g to encourage their acceptance with<strong>in</strong> the military. But hefaced a formidable task.In camps near the battlefront, life was far from be<strong>in</strong>g a model of fair play andtolerance. Commands with little faith <strong>in</strong> the combat skills of black soldiers rout<strong>in</strong>elyassigned them to segregated labor battalions, where they spent most of their time clean<strong>in</strong>glatr<strong>in</strong>es and perform<strong>in</strong>g other menial duties.Soon after arriv<strong>in</strong>g at Camp Darby to <strong>in</strong>spect the black troops, Gen. Davisdelivered a blister<strong>in</strong>g speech to the African-American service men of the 92 nd InfantryDivision.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Lee, the military’s highest-rank<strong>in</strong>g black officer told his soldiers,“You’ve got to DIE for your country and make a name for yourself!”Then th<strong>in</strong>gs got worse. Lee recalls Davis tell<strong>in</strong>g the stunned black trios, “You’remy COLOR but you’re not my KIND!”The former buffalo soldier shook his head slowly, a sly gr<strong>in</strong> on his face, “after hef<strong>in</strong>ished, nobody said a word.”Despite Davis’s <strong>in</strong>tervention—his noble, but misguided <strong>in</strong>tentions—the camp’sracial problems proved <strong>in</strong>tractable.“The 92 nd Infantry Division’s white soldiers,” Lee recalled “cont<strong>in</strong>ued to fight asa group, while the divisions Japanese-American soldiers fought alongside the <strong>Black</strong>-American soldiers.”

“The two groups of m<strong>in</strong>ority soldiers fought well together,” Lee <strong>in</strong>sisted, “withthe Nisei prov<strong>in</strong>g to be exceptionally tough, discipl<strong>in</strong>ed and brave.”Lee speaks with unbounded enthusiasm about the time his unit and Japanese-American soldiers helped clean out a division <strong>in</strong> the mounta<strong>in</strong> enclaves around Massa.“The Germans had a gun mounted on a long railroad flatbed and it was so big youcould almost crawl on your knees up the barrel,” said Lee. “The projectiles that came outweighed 600 pounds.”Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the <strong>World</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>II</strong> veteran, the flatbed would come out of the tunnel;the German soldiers would fire their huge gun and then the flatbed would disappear <strong>in</strong>tothe tunnel.Because of the enemy mach<strong>in</strong>e gun fire, land m<strong>in</strong>es and constant bombardmentfrom the hidden artillery piece, Lee’s unit found it impossible to advance. Whenever theenemy launched an attack, the men had to scramble.“You never could tell when ‘Jerry’ was go<strong>in</strong>g to come down and harass us,” Leerecalls.Each time the Germans fired their big 180 mm guns, scores of Allied soldiers andcivilians—most of them mothers with small children and elderly people who had nochoice but to rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the villages—lost their lives or were gravely <strong>in</strong>jured.Eventually, Lee’s <strong>in</strong>fantry unit figured out how to launch a successfulcounterattack.“We could p<strong>in</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t that doggone tunnel, drop 15 rounds <strong>in</strong>to that darn th<strong>in</strong>g andthere a<strong>in</strong>’t noth<strong>in</strong>g they could do,” asserted the feisty veteran. “In fact, several Britishunits and other Allied soldiers not only praise our group’s success, but often asked ‘Howdo you do that?’.”“The secret,” he expla<strong>in</strong>ed proudly, “was us<strong>in</strong>g high-angle fire,”Despite his wartime contributions, Lee often faced the same obstacle as his buddySpencer: a lack of recognition from superiors for a job well done. Though his artillerybattery successfully knocked out a destructive piece of artillery hidden <strong>in</strong> the mounta<strong>in</strong>tunnel, a big gun that killed and maimed hundreds of civilians and soldiers, his unit neverreceived a citation, he claims. Nor did the group receive a letter of recognition—thecustomary award for such a battlefield achievement.Despite the frustrations and humiliations of his war experience, Lee isnevertheless, a jovial, articulate and life-affirm<strong>in</strong>g man who often faces the <strong>in</strong>justices ofhis military past with a wry joke shared with fellow Buffalo Soldier Donald Spencer andother close friends <strong>in</strong> the Camp Darby community.Like Spencer, Fred Lee is at peace with his past and with his life <strong>in</strong> Italy, hisadopted country.