Ethnicity and Race in a Changing World

Volume 2, Issue 1, 2011 - Manchester University Press

Volume 2, Issue 1, 2011 - Manchester University Press

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

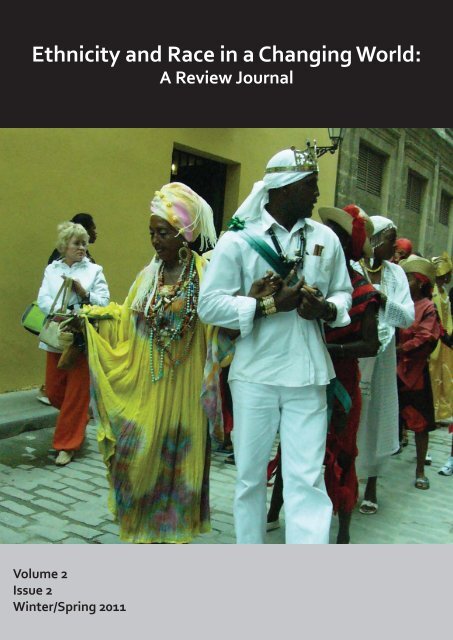

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>:A Review JournalVolume 2Issue 2W<strong>in</strong>ter/Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2011

Copyright © 2011 Manchester University PressWhile copyright <strong>in</strong> the journal as a whole is vested <strong>in</strong> Manchester University Press, copyright <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>dividual articles belongs to their respective authors <strong>and</strong> no chapters may be reproduced wholly or<strong>in</strong> part without the express permission <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g of both author <strong>and</strong> publisher. Articles, comments<strong>and</strong> reviews express only the personal views of the author.Published by Manchester University Press, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9NRwww.manchesteruniversitypress.co.ukISSN 1758-8685<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journal is a biannual journal, semi peer reviewed<strong>and</strong> freely available onl<strong>in</strong>e.Those plann<strong>in</strong>g to submit to the journal are advised to consult the guidel<strong>in</strong>es found on the website.The journal is created <strong>and</strong> edited by the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah <strong>Race</strong> Relations Resource Centre, Universityof Manchester, J Floor, Sackville Street Build<strong>in</strong>g, Sackville Street Area, M60 1QDTelephone: 0161 275 2920Email: racereviewjournal@manchester.ac.uk

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g<strong>World</strong>:A Review JournalVolume 2Issue 2W<strong>in</strong>ter/Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2011

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>:A Review JournalVolume 2, Issue 1, 2011Journal Editors:Emma Brita<strong>in</strong>, University of ManchesterJulie Devonald, University of ManchesterJournal Sub-editors:Ruth Tait, University of ManchesterAssociate Editors:Professor Emeritus Lou Kushnick, University of ManchesterChris Searle, University of ManchesterThe Editorial Board:Akwasi Assensoh, Professor, Indiana UniversityAlex<strong>and</strong>er O. Boulton, Professor, Stevenson UniversityAndrew Pilk<strong>in</strong>gton, Professor, University of Northampton <strong>and</strong> Director of Equality <strong>and</strong> Diversity Research GroupAubrey W. Bonnett, Professor, State University of New YorkBeverly Bunch-Lyons, Associate Professor, Virg<strong>in</strong>ia TechBrian Ward, Professor, University of ManchesterC. Richard K<strong>in</strong>g, Associate Professor, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton State UniversityCather<strong>in</strong>e Gomes, Dr., RMIT, University MelbourneCel<strong>in</strong>e-Marie Pascale, Assistant Professor, American UniversityDana-a<strong>in</strong> Davis, Associate Professor, Queens CollegeDavid Brown, Dr., University of ManchesterDavid Brunsma, Associate Professor, University of MissouriDavid Embrick, Assistant Professor, Loyola UniversityDorothy Aguilera, Assistant Professor, Lewis <strong>and</strong> Clark CollegeFazila Bhimji, Dr., University of Central LancashireGlenn Omatsu, Professor, California State UniversityH. L. T. Quan, Assistant Professor, Arizona Sate UniversityJames Frideres, Professor, University of Calgary <strong>and</strong> Director of International Indigenous StudiesJames Jenn<strong>in</strong>gs, Professor, Tufts UniversityJo Frankham, Dr., CERES, Liverpool John Moore’s University

Kris Clarke, Assistant Professor, California State UniversityLaura Penketh, Dr., University of ManchesterLionel M<strong>and</strong>y, Professor, California State UniversityLisa Maya Knauer, Professor, University of MassachusettsLucia Ann McSpadden, Coord<strong>in</strong>ator of International Support <strong>and</strong> Adjunct Faculty, Pacific School of ReligionMairela Nunez-Janes, Assistant Professor, University of North TexasMarta I. Cruz-Janzen, Professor, Florida Atlantic UniversityMelanie E. Bush, Assistant Professor, Adelphi UniversityMichele Simms-Burton, Associate Professor, Howard UniversityMojúbàolú Olúfúnké Okome, Professor, Brooklyn College, City University of New YorkMonica White Ndounou, Assistant Professor, Tufts UniversityNuran Savaskan Akdogan, Dr. , TODAIEPaul Okojie, Dr. , Manchester Metropolitan UniversityPedro Caban, Vice Provost for Diversity <strong>and</strong> Educational Equity, State University New YorkRaj<strong>in</strong>der Dudrah, Dr., University of ManchesterRichard Schur, Associate Professor <strong>and</strong> Director of Interdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary Studies, Drury UniversityRoderick D. Bush, Professor, St. John’s UniversityRol<strong>and</strong> Arm<strong>and</strong>o Alum, DeVry UniversitySamia Latif, Dr., University of ManchesterSilvia Carrasco Pons, Professor, Universitat Autonoma De BarcelonaTeal Rothschild, Associate Professor, Roger Williams UniversityThomas Blair, Editor, The ChronicleThomas J. Keil, Professor, Arizona State UniversityTraci P. Baxley, Assistant Professor, Florida Atlantic UniversityUvanney Maylor, Dr., London Metropolitan UniversityWillie J. Harrell, Jr., Associate Professor, Kent State UniversityZachary Williams, Assistant Professor, University of Akron

ContentsEditorial Statement:by Associate Editor, Professor Emeritus Louis KushnickiEssays:Consum<strong>in</strong>g Slavery, Perform<strong>in</strong>g Cuba: Ethnography, Carnival <strong>and</strong>Black Public Cultureby Lisa Maya Knauer, University of MassachusettsSouth Asian Mobilisation <strong>in</strong> Two Northern Cities: A Comparison ofManchester <strong>and</strong> Bradford Asian Youth Movementsby An<strong>and</strong>i Ramamurthy, Univesity of Central Lancashire326Comment <strong>and</strong> Op<strong>in</strong>ion:Blacks <strong>and</strong> the 2010 Midterms:A Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary Analysisby David A. BositisWilliam G. Allen <strong>in</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong>by Marika Sherwood4453Extended Book Review:The Transatlantic Indian, 1776 – 1930 Kate Fl<strong>in</strong>treview by Humaira Saeed68Book Reviews 72

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review JournalEditorial StatementWe are pleased to welcome you to the fouth Issue of the journal. This issue has two ma<strong>in</strong> essays, twocomment pieces <strong>and</strong> an extended review.The first essay is Consum<strong>in</strong>g Slavery, Perform<strong>in</strong>g Cuba: Ethnography, the Carnivalesque <strong>and</strong> the Politicsof Black Public Culture by Lisa M. Knauer, of the University of Massachusetts. The author explores ‘thepresences <strong>and</strong> absences of the history of slavery <strong>and</strong> its legacy <strong>in</strong> the heritage l<strong>and</strong>scape of Cuba’; <strong>and</strong>argues that ‘the way slavery is, <strong>and</strong>, more tell<strong>in</strong>gly, is not represented <strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> around heritage sites,historical narratives <strong>and</strong> cultural performances provides a lens for exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a larger ambivalenceconcern<strong>in</strong>g race <strong>in</strong> the Cuban national imag<strong>in</strong>ary.’Professor Knauer identifies <strong>and</strong> analyses the <strong>in</strong>terplay between two modes of cultural presentationthat she calls the ethnographic <strong>and</strong> the carv<strong>in</strong>alistic which the State <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>in</strong> Cuba deploy <strong>in</strong>their treatment of Black culture. After a critical analysis, she concludes that ‘the scholarly text, theethnographic display <strong>and</strong> the blatantly touristic commodity do not occupy completely separaterealms but are closely <strong>in</strong>terrelated registers through which slavery <strong>and</strong> its legacy are simultaneouslysilenced <strong>and</strong> consumed.’This essay has resonances for analyses of the ways <strong>in</strong> which the history of slavery <strong>and</strong> racial <strong>in</strong>equality<strong>and</strong> oppression are treated by public culture <strong>in</strong> other societies, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g modern advanced capitalistliberal democracies.Dr. An<strong>and</strong>i Ramamurthy’s essay, South Asian Mobilisation <strong>in</strong> Two Northern Cities: A Comparison ofManchester <strong>and</strong> Bradford Asian Youth Movements, is a valuable contribution to our underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g ofthe history of resistance aga<strong>in</strong>st racism by young members of Asian settler communities. The authoranalyses the development of the Asian Youth Movement <strong>in</strong> two cities, with very different demographic<strong>and</strong> political characteristics, <strong>in</strong> the late 1970s <strong>and</strong> early 1980s. Dr. Ramamurthy analyses their politicalpractice <strong>and</strong> ideas by reference to the towns <strong>and</strong> neighbourhoods <strong>in</strong> which they operated.She situates their development with<strong>in</strong> the wider political context of <strong>in</strong>stitutional racism <strong>and</strong> thecharacteristics <strong>and</strong> structures of the wider anti-racist movement. She has had access to participants<strong>in</strong> both cities <strong>and</strong> has conducted <strong>in</strong>-depth <strong>in</strong>terviews, which she contextualises <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporates <strong>in</strong>toa coherent, historically - <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutionally - anchored analysis. This is an important contribution tothe literature <strong>and</strong> we are pleased to be publish<strong>in</strong>g this essay.David Bositis has contributed a Comment Piece, Blacks <strong>and</strong> the 2010 Midterms: A Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary Analysis.Mr Bositis is a Senior Political Analyst for the Jo<strong>in</strong>t Center for Political <strong>and</strong> Economic Studies <strong>in</strong>Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC. He contributed a Comment <strong>in</strong> the first issue of this journal, Blacks <strong>and</strong> the 2008Elections: A Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary Analysis. He focuses on the behaviour <strong>and</strong> significance of African-Americanvoters <strong>in</strong> the 2010 Midterms, <strong>and</strong> argues that, although their vote was crucial <strong>in</strong> the outcome of someclosely contested elections, they were not <strong>in</strong> many more. He analyses the chang<strong>in</strong>g numbers <strong>and</strong>profile of Black c<strong>and</strong>idates for both federal <strong>and</strong> statewide office, as well as their performance <strong>in</strong> thepolls. As he has shown over the many years he has been on the staff of the Jo<strong>in</strong>t Center, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> hisanalyses which were published by this journal <strong>and</strong> its predecessor, Sage <strong>Race</strong> Relations Abstracts,Bositis shows a comm<strong>and</strong> of the data <strong>and</strong> provides a clear <strong>and</strong> comprehensive analysis.Marika Sherwood provides a biographical profile of William G. Allen <strong>and</strong> the time he spent withhis family <strong>in</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the ante-bellum <strong>and</strong> post-Civil War years. This is a well-researched <strong>and</strong>8

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journaldocumented Comment, <strong>in</strong> which she makes excellent use of primary sources. It is, also, a deeplymov<strong>in</strong>g account of the experiences of the highly educated free African-American <strong>in</strong> a Brita<strong>in</strong>, which,although conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g committed abolitionist supporters, had a dom<strong>in</strong>ant racist consciousness <strong>and</strong> aracially-justified imperial system. This racism framed <strong>and</strong> limited his opportunities <strong>in</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> asthe century advanced the situation for Blacks deteriorated <strong>and</strong> she concludes that his experienceswere symptomatic of “the superficiality of English politeness to people with a darker sk<strong>in</strong>.”We also have an Extended Review of Kate Fl<strong>in</strong>t’s book, The Transatlantic Indian, 1776 - 1930. This wellwritten<strong>and</strong> comprehensive review highlights Kate Fl<strong>in</strong>t’s analysis of how the image of the Indianbecame <strong>in</strong>tegral to the development of the United States as a new nation <strong>in</strong> the 19th century <strong>and</strong>was also central to British conceptualizations of the American cont<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formed the def<strong>in</strong>itions<strong>and</strong> ideological expressions of British national identity. These <strong>in</strong>cluded def<strong>in</strong>itions of mascul<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>and</strong>the disempowerment of women. Crucially, she also analyses the role of Native Americans as part of atransnational movement of culture, myth, image <strong>and</strong> folklore, as ‘material be<strong>in</strong>gs rather than simplyas symbols.’9

EssaysConsum<strong>in</strong>g Slavery, Perform<strong>in</strong>g Cuba: Ethnography, Carnival<strong>and</strong> Black Public Cultureby Professor Lisa Maya Knauer, University of MassachusettsSouth Asian Mobilisation <strong>in</strong> Two Northern Cities: A Comparisonof Manchester <strong>and</strong> Bradford Asian Youth Movementsby Dr. An<strong>and</strong>i Ramamurthy, Univesity of Central LancashirePeer Reviews for this issue were provided by:Dorothy Aguilera, Lewis <strong>and</strong> Clark CollegeEvan Smith, Fl<strong>in</strong>ders UniversityJohn Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Queens College, City University of New YorkJo Frankham, Liverpool John Moore’s UniversityLou Kushnick, University of ManchesterMarguerite Lukes, Metrotropolitan Centre for Urban Education, New York UniversityMonica White Ndounou, Tufts UniversityUvanney Maylor, London Metropolitan University

2<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journal

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review JournalConsum<strong>in</strong>g Slavery, Perform<strong>in</strong>g Cuba: Ethnography, Carnival<strong>and</strong> Black Public Culture 1Professor Lisa Maya Knauer, University of MassachusettsAnthropologist Michel-Ralph Trujillo notes that “any historical narrative is a particular bundle ofsilences.” 2 This article explores the silences <strong>and</strong> gaps around slavery <strong>and</strong> its legacy <strong>in</strong> the historicalnarratives that animate Cuba’s heritage l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>form cultural performances. I argue thatthe ways slavery is, <strong>and</strong>, more tell<strong>in</strong>gly, is not represented at heritage sites, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> State-sponsoredcultural performances provides a lens for exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a larger ambivalence concern<strong>in</strong>g race <strong>in</strong> theCuban national imag<strong>in</strong>ary. 3 Rather than focus<strong>in</strong>g on slavery as a mode of <strong>in</strong>stitutionalized violence, aset of social relations, <strong>and</strong> ideological structures, Cuban heritage narratives, cultural productions <strong>and</strong>visual representations highlight cultural contributions made by peoples of African descent to Cubannational identity. 4 While slave resistance is sometimes mentioned or enacted, racism <strong>and</strong> race areusually relegated to a fairly distant past. Cuban narratives thus downplay the racialized history of thenation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stead promote an <strong>in</strong>clusive, post-racial nationalism. It is as though enslaved people leftan impr<strong>in</strong>t, while the <strong>in</strong>stitutions, social relations <strong>and</strong> ideologies responsible for their enslavementvanished without a trace.In particular, I want to <strong>in</strong>terrogate the <strong>in</strong>tricate <strong>and</strong> dialectical <strong>in</strong>terplay between two modes ofcultural presentation that Cuban cultural <strong>in</strong>stitutions deploy <strong>in</strong> their treatment of Black culture that Icall “the ethnographic” <strong>and</strong> “the carnivalistic”. “The ethnographic” is a form of cultural presentationthat purports to be historically <strong>and</strong> cultural accurate or authentic (itself a problematic concept),often draw<strong>in</strong>g upon ethnographic research. “The carnivalistic” emphasizes spectacle, stag<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>and</strong> theatricalization. These are not, I argue, mutually exclusive or separate endeavors, cleanlydist<strong>in</strong>guished <strong>in</strong> time, space, or sponsorship, but can be compet<strong>in</strong>g or even complementary impulsesthat <strong>in</strong>form a s<strong>in</strong>gle museum display or music <strong>and</strong> dance performance. Nor are they the exclusiveprov<strong>in</strong>ce of State cultural functionaries, although most of the icons <strong>and</strong> performances I discuss areproduced <strong>and</strong> circulated with at least the tacit permission of the State, if not direct State sponsorship.Performers, vendors <strong>and</strong> ord<strong>in</strong>ary citizens, <strong>in</strong> Cuba as elsewhere, can adopt these modes of selfpresentationfor strategic or other reasons.My analysis is based on a close read<strong>in</strong>g of two sets of cultural productions. 5 First, I look at thecirculation <strong>and</strong> consumption of a series of <strong>in</strong>animate objects represent<strong>in</strong>g Black people <strong>and</strong> Blackculture <strong>in</strong> Cuba – pr<strong>in</strong>cipally dolls, small statues <strong>and</strong> carv<strong>in</strong>gs found at tourist sites <strong>and</strong> throughoutthe heritage l<strong>and</strong>scape – <strong>and</strong> also how these are animated by Cubans who perform these or similaridentities, particularly not<strong>in</strong>g which characters are m<strong>in</strong>imized or silenced <strong>in</strong> the tourist <strong>in</strong>dustry. I alsoexplore how similar icons are consumed <strong>and</strong> used <strong>in</strong> everyday sett<strong>in</strong>gs. I then exam<strong>in</strong>e more structuredcultural performances that actively encourage the enactment or representation of accepted slaveexperiences, focus<strong>in</strong>g on an annual re-enactment of a colonial-era “Black carnival” parade. 6The theatricalized spectacles seem, at first glance, to occupy a different register than the moreethnographically <strong>in</strong>formed representations <strong>in</strong> museums or discussions of Black culture <strong>in</strong> scholarlypublications. Yet, I argue, that they are part of a cont<strong>in</strong>uum. Each one references, <strong>in</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ct ways,a lengthy history of popular <strong>and</strong> high art renditions, folkloricized performances <strong>and</strong> ethnographicdisplays of Black-identified cultural forms <strong>in</strong> Cuba. S<strong>in</strong>ce most of these performances <strong>and</strong> sites comeunder the aegis of State cultural <strong>in</strong>stitutions, they can be seen as efforts to governmentalize <strong>and</strong>“conta<strong>in</strong>” Afrocuban religion <strong>and</strong> Black public culture through preservation <strong>and</strong> re-enactment. 7 Isuggest that the mean<strong>in</strong>gs of these productions are not static, nor are they determ<strong>in</strong>ed solely by3

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journalcultural <strong>and</strong> heritage officials. Instead, I view this terra<strong>in</strong> as a zone of friction, <strong>in</strong> which the (mostlyBlack) producers of these cultural performances, audiences as well as everyday Cuban citizens,actively complicate <strong>and</strong> contest the encoded mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> create counter-narratives, <strong>and</strong> use themto advance their own agendas. 8To contextualize my discussion of the <strong>in</strong>terplay between race <strong>and</strong> national identity <strong>in</strong> present-dayCuba, I start with a brief sketch of the emergence of the tourist economy, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g how both race<strong>and</strong> the commoditization of culture have been shaped by larger dynamics. While Cuba has its ownparticular constellation of ideologies <strong>and</strong> debates about racial <strong>and</strong> national identities, the ironies<strong>and</strong> frictions I discuss are not unique to the isl<strong>and</strong>. Nor is the commoditization of culture, usuallycomb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ethnographic <strong>and</strong> carnivalistic approaches, a recent development. However, it has becomemore ubiquitous than ever, <strong>and</strong> is a hallmark of neoliberalized development strategies <strong>and</strong> touristeconomies <strong>in</strong> many parts of the world. 9Old <strong>and</strong> new cultural economies of race <strong>in</strong> CubaRacial ambivalence came <strong>in</strong>to sharp relief immediately follow<strong>in</strong>g the collapse of the Soviet Union -a period of severe economic, social <strong>and</strong> political crisis <strong>in</strong> Cuba that the authorities euphemisticallylabeled “the special period <strong>in</strong> a time of peace”. In the wake of the loss of Soviet economic supports,the Cuban government shifted its economic policies to promote tourism as a source of hard currencyto prevent economic collapse <strong>and</strong> support social spend<strong>in</strong>g. While Cuba <strong>and</strong> its foreign <strong>in</strong>vestors havedeveloped numerous “sun <strong>and</strong> s<strong>and</strong>” resorts, there have also been efforts to promote cultural (<strong>and</strong>also medical) tourism. Consequently, the “heritage <strong>in</strong>dustry” has exploded as a result of foreign <strong>and</strong>domestic <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> heritage projects. These <strong>in</strong>clude museums, the reconstruction of HabanaVieja (Old Havana) under the aegis of UNESCO “patrimony of humanity” designation, <strong>and</strong> Cuba’scomponent of the transnational “Slave Routes” project. 10By the start of the twenty-first century, tourism revenues accounted for over a third of Cuba’s hardcurrency <strong>in</strong>come. 11 Although tourism fell off after September 11, 2001, it rema<strong>in</strong>s one of the largestsources of hard currency <strong>and</strong> is a pillar of Cuba’s economy. 12 At the same time, the Cuban governmentimplemented several other market-oriented <strong>in</strong>itiatives, such as re-establish<strong>in</strong>g farmers’ marketswhich allowed farmers to directly sell part of their yield to consumers, 13 <strong>and</strong> opened the door forcerta<strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ds of self-employment <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependently-owned small bus<strong>in</strong>esses. 14In 1993, the State legalized the possession of U.S. dollars <strong>and</strong> allowed ord<strong>in</strong>ary citizens to patronize thehard-currency stores which sold goods not available via the libreta (ration-book); these were formerlylimited to diplomats, other foreign visitors <strong>and</strong> party officials. The government also opened hundredsmore hard-currency stores, not only <strong>in</strong> tourist zones but <strong>in</strong> ord<strong>in</strong>ary residential neighborhoods <strong>in</strong>Havana <strong>and</strong> other cities. The dollarization <strong>and</strong> marketization of the economy was at the same timean effort to legalize <strong>and</strong> also regulate <strong>and</strong> conta<strong>in</strong> the vast <strong>in</strong>formal sector that had sprung up asthous<strong>and</strong>s of Cubans began to <strong>in</strong>ventar (literally, to <strong>in</strong>vent, but often mean<strong>in</strong>g “to hustle”), so thatthey could resolver (resolve) their economic needs <strong>in</strong> the wake of the economic collapse. 15This grow<strong>in</strong>g marketization, comb<strong>in</strong>ed with <strong>in</strong>creased numbers of both foreign <strong>and</strong> diasporic tourists,spurred consumption, consumerism, <strong>and</strong> the commercialization of daily life. 16 Some of Havana’s prerevolutionaryshopp<strong>in</strong>g streets that had fallen <strong>in</strong>to disuse or disrepair were refurbished <strong>and</strong> turnedback <strong>in</strong>to commercial zones. In residential neighborhoods like Cayo Hueso <strong>in</strong> Centro Habana (CentralHavana), streetscapes featured a mixture of small enterprises, Cuban peso stores <strong>and</strong> hard-currencystores. 17 By contrast, streets like Calle Obispo <strong>in</strong> the tourist zone of Habana Vieja are l<strong>in</strong>ed with manyupscale boutiques <strong>and</strong> eateries. 1997 saw the open<strong>in</strong>g of Havana’s first multi-story mall - <strong>and</strong> thefirst shopp<strong>in</strong>g center of any sort to be located <strong>in</strong> an historically “<strong>in</strong>ner city” neighborhood - the PlazaCarlos III. Dur<strong>in</strong>g my years of field visits to Centro Habana, the mall was usually crowded, with people4

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journalcongregat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the downstairs food court <strong>and</strong> the sidewalk outside the ma<strong>in</strong> entrance. Cubans soughtnot only daily necessities like soap <strong>and</strong> cook<strong>in</strong>g oil that had been <strong>in</strong> short supply dur<strong>in</strong>g the harshestyears of the special period but br<strong>and</strong>-name cloth<strong>in</strong>g, electronics <strong>and</strong> other consumer goods sportedby tourists <strong>and</strong> available at relatively high prices <strong>in</strong> State-owned hard currency stores (or <strong>in</strong> the stillvibrant<strong>in</strong>formal economy). 18 Go<strong>in</strong>g to la shopp<strong>in</strong>g - Cuban slang for a hard-currency store - becamea daily activity <strong>and</strong>, for many, a form of enterta<strong>in</strong>ment. 19As hotels, resorts, hard-currency stores <strong>and</strong> small enterprises have mushroomed, Cuban culture,<strong>and</strong> especially Black-identified culture, has become <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly commoditized <strong>and</strong> packaged fortouristic consumption. And here<strong>in</strong> lie some of the most potent ironies. Recent studies, most notablyby Cuba’s Centro de Antropología (Anthropology Center), have substantiated what many scholars<strong>and</strong> others argued earlier based upon anecdotal evidence: that the marketization of Cuba, its rearticulation<strong>in</strong>to the global economy through tourism, assorted jo<strong>in</strong>t ventures <strong>and</strong> remittances, havehelped produce new forms of stratification <strong>and</strong> possibly a nascent class formation, whose contoursare <strong>in</strong>fluenced by race, gender <strong>and</strong> geography. Blacks have a harder time f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g a foothold <strong>in</strong> somesectors of what scholars are label<strong>in</strong>g the “emergent economy” (front-desk jobs <strong>in</strong> tourism <strong>and</strong> jo<strong>in</strong>tenterprises). Instead, they are hired for more menial jobs <strong>in</strong> tourism such as chambermaid, waiters,park<strong>in</strong>g attendants, doormen <strong>and</strong> bellhops. 20 Blacks receive less remittance money from relatives<strong>in</strong> the diaspora to f<strong>in</strong>ance self-owned bus<strong>in</strong>esses, <strong>and</strong> therefore seek opportunity <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>formalsector. Black men are over-represented <strong>in</strong> the ranks of street hustlers, or j<strong>in</strong>eteros, who frequenttourist locales. Rehears<strong>in</strong>g racialized (<strong>and</strong> gendered) tropes that date back over a century, Blackwomen’s bodies (<strong>and</strong> to a degree, Black men’s bodies) are highly desirable commodities for foreigntourists seek<strong>in</strong>g sexual adventure. 21 Black male bodies are still construed as dangerous <strong>and</strong> disruptive<strong>in</strong> public space (<strong>and</strong> commoditized private spaces such as resorts), <strong>and</strong> Black men are subject todisproportionate surveillance by police <strong>and</strong> hotel <strong>and</strong> resort staff.That race is be<strong>in</strong>g discussed at all – the Centro de Antropología’s research was covered <strong>in</strong> Granma,the official Communist Party daily newspaper - represents a shift. However, official discourse largelydescribes racism as a matter of prejudiced views held by <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong> an unfortunate legacy ofthe past. It thus sidesteps <strong>in</strong>stitutional or structural factors -- such as the historical ambivalenceconcern<strong>in</strong>g whether Blacks could ever be good Cuban citizens, <strong>and</strong> the post-revolutionary silenc<strong>in</strong>gof discussions of race. 22At the same time Blackness has become a desirable commodity <strong>in</strong> other arenas of the touristeconomy. 23 Cultural practices marked as “Black” – folkloric music, dance <strong>and</strong> “religions of Africanorig<strong>in</strong>” – which the authorities formerly frowned upon <strong>and</strong> discouraged, or sought to convert <strong>in</strong>tovehicles for the promotion of socialist values - have been turned <strong>in</strong>to valuable cultural currency.Foreign <strong>and</strong> Cuban tour operators offer opportunities to study “traditional” Afrocuban music <strong>and</strong>dance <strong>and</strong> observe religious ceremonies. 24 Some enterpris<strong>in</strong>g santeros <strong>and</strong> santeras (santeria priests<strong>and</strong> priestesses) <strong>and</strong> other Afrocuban religious specialists have been able to register their homesas State-recognized cultural centers. 25 Many performers, artisans, <strong>and</strong> religious practitioners havethus been able to parlay their expertise (real or ascribed) <strong>in</strong> Black culture <strong>in</strong>to a means of support<strong>in</strong>gthemselves <strong>and</strong> their families.As I detail below, performances, museum displays <strong>and</strong> tourist souvenirs re<strong>in</strong>force deeply embeddedracialized <strong>and</strong> gendered images. For example, Havana’s legendary Tropicana nightclub, which datesback to the late 1930s when Cuba was promoted as a tropical paradise for thrill-seek<strong>in</strong>g foreigners,still presents nightly cabaret performances featur<strong>in</strong>g a chorus l<strong>in</strong>e of statuesque <strong>and</strong> scantily cladmulata (light-sk<strong>in</strong>ned Black women) dancers. 26 The expansion of the tourist <strong>in</strong>dustry led to the recentopen<strong>in</strong>g of two additional branches of the Tropicana <strong>in</strong> Cuba’s eastern city of Santiago <strong>and</strong> near thebeach resort of Varadero. The music <strong>and</strong> dance revues at the Tropicana <strong>and</strong> other cabarets usually5

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journaloffer highly stylized <strong>and</strong> sometimes quite fanciful versions of Black-identified “folkloric” genres likerumba <strong>and</strong> Afrocuban religious music <strong>and</strong> dance, 27 along with guest appearances by more “traditional”performers of Afrocuban folkloric music. Meanwhile, there has been a small explosion of open-air <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>door venues for more “authentic” Afrocuban folkloric music (along with the emergence of severalnew folkloric ensembles seek<strong>in</strong>g performance opportunities).The upbeat, celebratory tone of most of these performances, <strong>and</strong> the emphasis on festive ethnicity,the folkloristic <strong>and</strong> the performative fit well with the government’s promotion of a raceless or racially<strong>in</strong>clusive nationalism. 28 Emcees at cultural performances frequently recite José Martí’s aphorism, “InCuba there will never be a race war … Cuban is more than White, more than mulatto, more thanBlack…” 29 The hit song “La Vida es Un Carnaval”, popularized on the isl<strong>and</strong> by Isaac Delgado, couldwell serve as a musical version of one of the carnivalistic master tropes deployed by the State tourist<strong>in</strong>dustry – a sun-drenched isl<strong>and</strong> paradise where people s<strong>in</strong>g their cares away (the song’s chorusexhorts the listener, “Ay, there’s no need to cry, life is a carnival, <strong>and</strong> s<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g will take away yourcares.”) 30The performativity of these varied registers of cultural production – the breath<strong>in</strong>g actors alongsidethe static icons - must be <strong>in</strong>terpreted with<strong>in</strong> the context of Cuba’s heritage l<strong>and</strong>scape, which hasbeen shaped by the <strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>g, sometimes complementary <strong>and</strong> sometimes compet<strong>in</strong>g desires, <strong>and</strong>projects, of global capital, the Cuban State, cultural promoters, cultural producers <strong>and</strong> performers,everyday Cuban citizens, <strong>and</strong> tourists. In this contact zone, varied imag<strong>in</strong>aries <strong>and</strong> identities areconstructed, narrated, negotiated <strong>and</strong> contested. As Da<strong>in</strong>a Harvey notes <strong>in</strong> her discussion of Blackheritage sites <strong>in</strong> New Jersey, spaces are experienced differently by tourists <strong>and</strong> residents. 31 Thepromotion of these images, objects <strong>and</strong> performances by both public <strong>and</strong> private actors <strong>in</strong> the tourist<strong>and</strong> heritage <strong>in</strong>dustries speaks volumes about the racialized <strong>and</strong> gendered cultural economy ofcontemporary Cuba.The performative spectacles, both the ethnographic reconstructions <strong>and</strong> the everyday commoditizedenactments, are set with<strong>in</strong> a heritage l<strong>and</strong>scape that avoids mention of racial disharmony, past orpresent, or, largely, of slavery itself except safely enshr<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>side museums, <strong>and</strong> there usually onlyobliquely. The idealized qua<strong>in</strong>tness of the restoration of Habana Vieja is itself a k<strong>in</strong>d of Whitefacem<strong>in</strong>strelsy: it evokes the glory of the Spanish colonial past while never mention<strong>in</strong>g colonialism.Urban spaces are palimpsests, but historic restorations or reconstructions are always selective <strong>in</strong> theslices or fragments of the past they chose to recover or recreate; they <strong>in</strong>evitably omit or suppresscerta<strong>in</strong> narratives while refram<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g others. In select<strong>in</strong>g one particular historic freezeframe,even the most faithful reproduction (<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g legions of archaeologists <strong>and</strong> architecturalhistorians) ignores everyth<strong>in</strong>g that preceded or followed it. 32 History often becomes a vehicle topromote consumption, particularly by foreign tourists. Further, plann<strong>in</strong>g decisions are usually madeby developers, bureaucrats <strong>and</strong> experts; present-day residents of the surround<strong>in</strong>g area are either leftout or given limited voice. 33The Centro Histórico (historic center) of Habana Vieja was restored <strong>and</strong> reconstructed under theauspices the Office of the City Historian of Havana (referred to here<strong>in</strong> by its Spanish acronym OHCH).OHCH is a unique semi-autonomous governmental agency that has been charged with supervis<strong>in</strong>gthe reconstruction of Old Havana <strong>and</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g tourist development. 34 The Cuban government hasgiven the OHCH extraord<strong>in</strong>ary powers to raise revenues for reconstruction through tour agencies,commercial ventures, <strong>and</strong> admission fees to museums, pseudo-museums <strong>and</strong> historic sites, <strong>and</strong> toestablish jo<strong>in</strong>t ventures with foreign companies <strong>and</strong> governments. 35 The governments of Spa<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong>the Canary Isl<strong>and</strong>s (<strong>and</strong> also Spanish banks) underwrote much of the reconstruction of Habana Vieja,spark<strong>in</strong>g quips that this amounted to a reconquista or reconquest by the former colonial power, acentury after <strong>in</strong>dependence.6

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review JournalThere is little <strong>in</strong> the historic center that directly signals the presence of enslaved (<strong>and</strong> some free)Africans who undoubtedly contributed much of the labor that built the houses, founta<strong>in</strong>s, churches,<strong>and</strong> laid the pav<strong>in</strong>g stones. A recent mural depict<strong>in</strong>g Havana “society” of the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century<strong>in</strong>cludes two or three Black faces (see figure 1). More alarm<strong>in</strong>gly, the whitewashed facades of themajestic Plaza Vieja are narrated by a billboard with a bl<strong>and</strong>ly nationalistic quote from José AntonioSaco, the chief promoter of the colonial-era policy of blanqueamiento - whiten<strong>in</strong>g Cuba’s populationthrough <strong>in</strong>creased Spanish immigration. The specter of Haiti as the world’s first free Black republichaunted n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century Cuba, <strong>and</strong> the explosion of the Black population produced by Cuba’ssugar boom stoked racial fears even with<strong>in</strong> the anti-colonialist movement. Saco <strong>and</strong> many othersnow heralded as great Cuban nationalists did not want a Cuba libre (free Cuba) with a Black majority.The silenc<strong>in</strong>g of this narrative produces a weird k<strong>in</strong>d of kaleidescop<strong>in</strong>g; by ignor<strong>in</strong>g or delet<strong>in</strong>g anymention of these past efforts to literally whitewash Cuba’s population, the authors <strong>and</strong> architects ofthese <strong>and</strong> other historic sites also whitewash the racially troubled present, <strong>and</strong> deflect any suggestionFigure 1: A recently-<strong>in</strong>stalled mural depict<strong>in</strong>g n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century Havana society, on a busy pedestrian street <strong>in</strong> theCentro Históricothat race cont<strong>in</strong>ues to be an issue <strong>in</strong> Cuba. There is noth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the official signage to unsettle theclaim that Cuba is a raceless society.The absence of direct reference to slavery <strong>in</strong> Havana’s historic (<strong>and</strong> touristic) center contrastswith the hulk<strong>in</strong>g socialist realism of the Monument to Carlota’s Rebellion, commemorat<strong>in</strong>g an<strong>in</strong>eteenth century slave upris<strong>in</strong>g (see Figure 2). This impos<strong>in</strong>g sculpture, however, is located <strong>in</strong> anisolated (although strik<strong>in</strong>gly beautiful) corner of Matanzas prov<strong>in</strong>ce. When I visited <strong>in</strong> June 2007,accompanied by an official of the prov<strong>in</strong>cial Department of Patrimony, we were the only visitors.Cuba participated <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itial UNESCO-sponsored discussions that led to the Slave Routes (La Rutadel Esclavo) <strong>in</strong>itiative, <strong>and</strong> has identified <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ventoried numerous sites of historic significance -ru<strong>in</strong>s of plantations, sugar mills, slave barracks or barracones, slave cemeteries, many of which arelocated well outside of Havana, <strong>in</strong> what anthropologist Anna Ts<strong>in</strong>g calls “out of the way places”. 36 TheMuseum of the Slave Route is housed <strong>in</strong> the restored Castillo de San Sever<strong>in</strong>o, on the outskirts of thecity of Matanzas, <strong>and</strong> is not easily accessible except by automobile or tour bus. 37 Matanzas boasts7

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journalmany beautiful colonial-era build<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> is recognized asa center of Afrocuban religion <strong>and</strong> music, <strong>and</strong> it is not farfrom the resort town of Varadero, but many tourists headstraight for the beaches. 38Objectify<strong>in</strong>g (<strong>and</strong> sell<strong>in</strong>g) BlacknessWith this contextual sketch, I now turn to the objects<strong>and</strong> performances. My analysis beg<strong>in</strong>s with the nearlyubiquitous figure of a Black female doll I purchased at atourist shop <strong>in</strong> Habana Vieja (see figure 4). These dolls,which come <strong>in</strong> varied sizes, are made of Black cloth <strong>and</strong>dressed <strong>in</strong> colonial-era dresses, often covered with anapron. Characteristically, they wear match<strong>in</strong>g headscarves<strong>and</strong> sometimes golden-colored hoop earr<strong>in</strong>gs. The dollsare available from street vendors <strong>and</strong> at souvenir shopsthroughout the Centro Histórico, <strong>and</strong> also at h<strong>and</strong>icraftmarkets <strong>and</strong> tourist shops across the isl<strong>and</strong>. Similardolls are sold at tourist sites throughout the Caribbean;when I presented a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary version of this article at aconference <strong>in</strong> Barbados, <strong>and</strong> held up my Cuban doll, severalpeople asked me if I had purchased the doll <strong>in</strong> Barbados.Figure 2Other images of Blackness are on display <strong>and</strong> for sale <strong>in</strong> tourist areas <strong>and</strong> museums throughout theisl<strong>and</strong>. Carved wooden statues, pa<strong>in</strong>ted ceramic figur<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs rehearse other racialized <strong>and</strong>gendered tropes that are part of both the national <strong>and</strong> touristic imag<strong>in</strong>aries: the smil<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> everavailablemulata, usually clad <strong>in</strong> a sk<strong>in</strong>-tight dress emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g her ample hips <strong>and</strong> bosom, whichis sometimes barely conta<strong>in</strong>ed by the dress, <strong>and</strong> jovial Black men roll<strong>in</strong>g cigars, play<strong>in</strong>g drums orhold<strong>in</strong>g serv<strong>in</strong>g trays. Some of these figures are relatively realistic, but others are gross caricatures,with bulbous lips, or extravagantly exaggerated breasts <strong>and</strong> bottoms.Silenced are the stories of the orig<strong>in</strong>s of these figures: their post-colonial m<strong>in</strong>strelsy has roots <strong>in</strong> theexoticized caricatures or more romanticized representations of the colonial imag<strong>in</strong>ary: the Blackfacetheater, negrista literature <strong>and</strong> costumbrista visual arts that flourished <strong>in</strong> n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuryHavana. 39 What makes these images problematic is not solely the nature of the tropes themselves,but also the contexts <strong>in</strong> which they are dissem<strong>in</strong>ated. All of the venues where these icons are soldare either licensed or run by State enterprises. Here images of smil<strong>in</strong>g complacency, servility <strong>and</strong>sexual availability – the enslaved or subord<strong>in</strong>ate status often implied rather than articulated - arejuxtaposed with equally exoticized but more generic “African” style carv<strong>in</strong>gs that began to appear<strong>in</strong> Cuba’s tourist zones <strong>in</strong> the 1990s, <strong>and</strong> other more genu<strong>in</strong>ely national icons such as h<strong>and</strong>-rolledcigars, bottles of rum <strong>and</strong> the superficially more rebellious visage of Che Guevara that is endlesslyreproduced on t-shirts, caps or newspapers. 40Vendors, of course, offer what they th<strong>in</strong>k the tourists want. But very little takes place <strong>in</strong> the CentroHistórico without the permission or imprimatur of the Office of the City Historian of Havana. All ofthe vendors operat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the historic district, whether <strong>in</strong> stores or st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the artisans’ fair, must belicensed by the OHCH, <strong>and</strong> the OHCH’s power to award (or deny) licenses is a source of contention forlocal residents who want to operate small bus<strong>in</strong>esses.These k<strong>in</strong>ds of carnivalistic figur<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> dolls are sold not only <strong>in</strong> stores <strong>and</strong> fairs that are clearlycommercial <strong>and</strong> geared towards tourists, but also at gift shops <strong>in</strong> ostensibly more high-m<strong>in</strong>dedmuseums. Figure 3 shows a shelf <strong>in</strong> the gift shop at the Museo Histórico de Guanabacoa (the Historical8

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review JournalMuseum of Guanabacoa), a municipal museum with a more serious ethnographic <strong>and</strong> historicalmission, <strong>and</strong> one that is <strong>in</strong>ternationally recognized for its carefully designed <strong>and</strong> “authentic” dioramicdisplays of Cuba’s religions of African orig<strong>in</strong>. 41 Similar figures are sold at other equally high-m<strong>in</strong>dedmuseums. 42The high-art <strong>and</strong> commercial orig<strong>in</strong>als of these archetypes are on display at the newly refurbishedMuseum of F<strong>in</strong>e Arts <strong>in</strong> Habana Vieja. A small room tucked away off the ma<strong>in</strong> exhibition spaceconta<strong>in</strong>s an exhibit devoted entirely to the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century tobacco marquillas (cigar box labels),lavishly illustrated by some of the most noted artists of the day, often with scenes of plantation <strong>and</strong>Black urban life; they are a rich source of <strong>in</strong>formation about the highly gendered racial economy ofcolonial Cuba. 43 In addition, there are several pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs by French artist Victor L<strong>and</strong>aluze, who wascelebrated for his colorful <strong>and</strong> “authentic” depictions of everyday scenes of Black urban life <strong>in</strong> Cuba.D<strong>and</strong>ified Black men <strong>in</strong> brightly colored cloth<strong>in</strong>g swagger <strong>and</strong> flirt with equally resplendent women.Completely absent is any curatorial or critical commentary about costumbrismo, the colonial gaze,or slavery; <strong>in</strong>deed few works are even labeled. 44These figures are further complicated by the existence of their real-life counterparts on the streetsoutside. The sweep<strong>in</strong>g plazas of Habana Vieja, many now restored or refashioned a nearly-prist<strong>in</strong>ecolonial-era veneer, are also stages for costumed men <strong>and</strong> women (mostly women) who seem tohave stepped out of the costumbrista canvases <strong>in</strong>side the museum. In front of Havana’s massiveseventeenth century cathedral a heavy-set, dark sk<strong>in</strong>ned, middle aged woman, sits at a small table<strong>and</strong> offers spiritual advice <strong>and</strong> read<strong>in</strong>gs. She is dressed <strong>in</strong> volum<strong>in</strong>ous white skirts <strong>and</strong> a headscarf,<strong>and</strong> wears numerous beaded necklaces; for many Cubans <strong>and</strong> some foreign visitors familiar withAfrocuban religions, these are easily legible symbols of religious affiliation. 45 She frequently puffs ona fat cigar (which doubles as a national <strong>and</strong> religious icon) <strong>and</strong> can be found here year round. Thereare a few other similarly outfitted women <strong>in</strong> different sites throughout the Centro Histórico, althoughnone seem quite as emplaced <strong>and</strong> authoritative as she.Occupy<strong>in</strong>g a slightly different niche <strong>in</strong> the tourist imag<strong>in</strong>ary are several younger, more nubile womenenact<strong>in</strong>g the roles of colonial-era vendors, dressed <strong>in</strong> colorful flow<strong>in</strong>g gowns, bear<strong>in</strong>g baskets ofFigure 3: Gift shop, Museo Historico de Guanabacoa9

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journalflowers or fruits <strong>and</strong> bright smiles. Where the older women are stationary, planted <strong>in</strong> their spots,the younger women are mobile, approach<strong>in</strong>g tourists as they are disgorged from buses or simplyw<strong>and</strong>er<strong>in</strong>g on foot through the historic district, offer<strong>in</strong>g to pose for photographs for a small fee. Thesomewhat more abject or rebellious figures of the male slaves, usually <strong>in</strong> small ceramic figures orwooden carv<strong>in</strong>gs, do not have real-life counterparts outside of staged folkloric performances, manyof which <strong>in</strong>clude a choreographed set piece of a slave revolt, but the carved <strong>and</strong> pa<strong>in</strong>ted waiters <strong>and</strong>musicians come to life <strong>in</strong> tourist spots across the country. Hundreds of professional musicians – amajority of whom, for historic reasons, are Black men, all of whom are State employees – regalepatrons at <strong>in</strong>door <strong>and</strong> open-air bars, cafes <strong>and</strong> restaurants, while other men (<strong>and</strong> some women) –many of whom are Black - prepare <strong>and</strong> serve the food <strong>and</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k that the patrons consume. 46While a full analysis of each of these iconic images <strong>and</strong> performances would be an <strong>in</strong>trigu<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>useful exercise, it is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is worth delv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to one commonfigure, the dark-sk<strong>in</strong>ned female cloth doll who looks like a Cuban counterpart to the “Aunt Jemima” or“mammy” dolls <strong>in</strong> the U.S., <strong>and</strong> who has a complicated legacy <strong>in</strong> Cuban popular culture. 47 The stout,dark-sk<strong>in</strong>ned woman wear<strong>in</strong>g a head wrap was a popular image <strong>in</strong> n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century marquillas,which are a rich source for study<strong>in</strong>g racial <strong>and</strong> gender ideologies <strong>in</strong> colonial Cuba. Well-known f<strong>in</strong>eartists such as Victor L<strong>and</strong>aluze created designs for many of the labels, <strong>and</strong> they blur the boundariesbetween high art <strong>and</strong> commercial culture. Although Jill Lane argues that Blackface m<strong>in</strong>strelsy wassometimes used for anti-colonial ends, the visual narratives <strong>in</strong> the marquillas often played outracialized fears about Cuba’s future <strong>and</strong> specifically the place of Blacks. 48 The dark-sk<strong>in</strong>ned womanor negra <strong>in</strong> the tobacco marquillas is often the mother of the light-sk<strong>in</strong>ned mulata, who is depictedas allur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> highly desirable. She reflects a national racial/gender ideal. While the negra is thusimplicitly or overtly the sexual partner of a White man, she is never his wife, <strong>and</strong> the visual portrayal oftheir relationship sometimes suggests rape or seduction on the one h<strong>and</strong>, or a commercial transactionon the other. While the dark-sk<strong>in</strong>ned woman is thus shown as a sexual be<strong>in</strong>g (unlike some of the moredesexualized portrayals of dark-sk<strong>in</strong>ned Black women <strong>in</strong> U.S. popular cultural iconography), she isclearly less desirable than, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ferior to, her lighter-sk<strong>in</strong>ned offspr<strong>in</strong>g. 49However, turn<strong>in</strong>g an ethnographic lens on how the dolls <strong>in</strong> circulation today are consumed, we f<strong>in</strong>dthat not all are purchased by tourists. I saw numerous dark-sk<strong>in</strong>ned female dolls with head wraps-- sometimes older, visibly careworn, <strong>and</strong> with less exaggerated features -- <strong>in</strong> the homes of Cubanfriends. In some cases they were simply decorative items, placed on crocheted doilies on a sofa orshelf, but often they were part of an altar for one of the African-orig<strong>in</strong> religions. In these contexts adoll may personify a person’s spirit guide <strong>in</strong> espiritismo (spiritism), one of the orishas <strong>in</strong> la regla deocha or santeria (the deities Yemayá <strong>and</strong> Oyá are both represented as dark-sk<strong>in</strong>ned Black women), ora similarly powerful female figure <strong>in</strong> Palo Monte. The dolls serve as entry po<strong>in</strong>ts for the div<strong>in</strong>e heal<strong>in</strong>genergies of these religious practices, <strong>and</strong> are thus sacred items. When I photographed my friendCaridad Moré, she chose to sit <strong>in</strong> front of her altar with one of her dolls <strong>in</strong> her arms (see Figure 4).As material cultural artifacts associated with African-orig<strong>in</strong> religions, older dolls which are no longerused for religious purposes have passed <strong>in</strong>to the collections of museums with ethnographic displaysdevoted to these religions such as the Historical Museum of Guanabacoa or Casa de Africa, becom<strong>in</strong>g“objects of ethnography.” 50 Their real-life counterparts are not limited to the self-exoticiz<strong>in</strong>g fortunetellers of Habana Vieja, but can be found <strong>in</strong> religious ceremonies, markets <strong>and</strong> households across theisl<strong>and</strong>.Aside from a few scholars <strong>and</strong> artists, few Cubans (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Black Cubans) seemed troubled by theseimages. They have become naturalized as part of the isl<strong>and</strong>’s visual iconography <strong>and</strong> abound <strong>in</strong> localdomestic material culture. An African American female scholar reported question<strong>in</strong>g some vendors<strong>in</strong> old Havana (while try<strong>in</strong>g to conceal her own troubled response to the images). She noted that they10

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journalseemed genu<strong>in</strong>ely proud of the items, <strong>and</strong> thought them beautiful <strong>and</strong> important representations ofauthentic Cubanness with no trace of irony. 51Alexis Esquivel, a Cuban artist whose work critically <strong>in</strong>terrogates race, has produced a series ofpa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> performances based on these dolls. He noted that many Cuban viewers do not “get”the critical component of his work but <strong>in</strong>stead view the pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs as high-end, slightly abstractedversions of the kitschy popular culture items. To underscore how much these stereotyped imageshave become normalized <strong>and</strong> taken for granted, he added that s<strong>in</strong>ce he purchases dolls as modelsfor pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs or to <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong> performances, once he has f<strong>in</strong>ished us<strong>in</strong>g the dolls, his mother asks forthem afterwards to decorate her apartment. 52Figure 4Perform<strong>in</strong>g the nationI now turn to a fully theatricalized performance draw<strong>in</strong>g upon Afrocuban religious music <strong>and</strong> imagery.For the last decade or so, on January 6 at around mid-day, a festive, noisy <strong>and</strong> colorful parade hassnaked its way around the streets of Habana Vieja. Led by a regally-attired couple, the K<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>Queen of the parade (see figure 5), the event labeled “La Salida de los Cabildos” is sponsored byCasa de Africa (Africa House), a museum that houses a substantial part of the collection of Fern<strong>and</strong>oOrtíz, often heralded <strong>in</strong> scholarly <strong>and</strong> bureaucratic discourse as “the third discoverer of Cuba” for hisefforts to document <strong>and</strong> legitimate African-derived religious <strong>and</strong> musical practices as authentic <strong>and</strong>essential components of the ajiaco or “stew” of Cuban national cultural identity. 53 And the date ofthis procession – January 6 – was not r<strong>and</strong>omly chosen. The procession purports to be a recreation ofthe Día de los Reyes (literally, “day of the k<strong>in</strong>gs” but usually translated <strong>in</strong>to English as Three K<strong>in</strong>gs’Day), the Feast of the Epiphany on the Catholic calendar. Dur<strong>in</strong>g Spanish rule this was the only daywhen Havana’s substantial population of Africans <strong>and</strong> their descendants – both free <strong>and</strong> enslaved– were permitted to “go out” (salir) onto the city streets with drums <strong>and</strong> costumes <strong>and</strong> “performthemselves”.11

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review JournalThe exact it<strong>in</strong>erary of the recreated parade varies from year to year, as the parade organizers mustfactor <strong>in</strong> the State of reconstruction <strong>and</strong> preservation efforts, <strong>and</strong> both performers <strong>and</strong> the ambulatoryaudience must work their way around scaffold<strong>in</strong>g, wooden beams <strong>and</strong> potholes. However, unlikethe quotidian <strong>and</strong> more <strong>in</strong>formal cultural performances described above, the modern-day paradewas designed as a somewhat more high-m<strong>in</strong>ded endeavor <strong>and</strong> attempts to provide an “authentic”representation of the African contributions to Cuban culture. At each of the central plazas, theprocession stops <strong>and</strong> performers present a short set piece of music <strong>and</strong> dance from one of the sacredAfrocuban traditions: the regla de ocha or santeria (derived from the Yoruba-speak<strong>in</strong>g peoples ofwhat is now Nigeria), Palo Monte (based on Bantu or Congo cultures of West-Central Africa), <strong>and</strong> themasked dancers, called iremes or diablitos (“little devils”) of the all-male Abakuá secret society (basedupon similar sodalities <strong>in</strong> the Calabar region of what is now Nigeria). However, for the pass<strong>in</strong>g tourist,there is little to dist<strong>in</strong>guish this once-a-year parade from the everyday, more overtly commoditizedspectacles that I have just described; there is no emcee or explanatory brochure.The event of which it is a somewhat aestheticized <strong>and</strong> fanciful re<strong>in</strong>terpretation, the Díia de los Reyes,is part of the complex <strong>and</strong> doubly bifurcated carnival tradition <strong>in</strong> Cuba. 54 The modern-day event, theSalida de los Cabildos, takes its name from the one form of socio-cultural organization that Blackswere permitted dur<strong>in</strong>g the tiempo de la colonia (colonial times) – the mutual aid societies calledcabildos. The cabildos, orig<strong>in</strong>ally established under the auspices of the Catholic Church, were relativelyautonomous <strong>and</strong> established theirown <strong>in</strong>ternal social organization. Theywere often able to purchase build<strong>in</strong>gs<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> (as well as the freedom oftheir enslaved members), <strong>and</strong> s<strong>in</strong>cethe authorities often left them alone,they provided a fertile ground for thepreservation or recreation of Africanreligious <strong>and</strong> cultural practices. 55Dur<strong>in</strong>g the colonial period, Havana,like many other cities <strong>in</strong> the circum-Caribbean, had Black <strong>and</strong> Whitecarnivals that were separatedspatially <strong>and</strong> temporally. The Creole(isl<strong>and</strong>-born) elite held a pre-LentenCarnival rooted <strong>in</strong> medieval Europeantraditions. Blacks were only allowedto participate <strong>in</strong> the White carnival <strong>in</strong>a limited way <strong>and</strong> were to organizetheir own comparsas (street b<strong>and</strong>s).However, Blacks were allowed toparade <strong>in</strong> the streets with costumes<strong>and</strong> comparsas on January 6. WhileBlacks reveled <strong>in</strong> the streets <strong>and</strong>plazas, Whites watched from thesafety of their balconies. The streetsof the old city, on that day, were aBlack space. The closest we have toan ethnographic or historical recordof these events are a few verbal <strong>and</strong>Figure 512

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review Journalvisual sketches, mostly from European visitors, <strong>and</strong> some police records. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to these accounts,the Día de los Reyes was exuberant, festive <strong>and</strong> noisy.The Día de los Reyes, like other forms of Black cultural production, especially those <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g drums<strong>and</strong> disorder (real or imag<strong>in</strong>ed), was subject to discipl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> repression by the colonial authorities.Dur<strong>in</strong>g Cuba’s protracted wars of <strong>in</strong>dependence (start<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the 1860s), colonial officials <strong>and</strong> the elitefeared that Blacks might jo<strong>in</strong> the anti-colonial struggle or revolt on their own. The authorities closeddown many cabildos, <strong>and</strong> the Día de los Reyes was restricted <strong>and</strong> eventually banned <strong>in</strong> the mid-1880s. 57 Accord<strong>in</strong>g to older Habaneros (Havana residents), people cont<strong>in</strong>ued to celebrate the Día delos Reyes but <strong>in</strong> smaller, more private ways. 58Most of the actual cabildos, the mutual aid societies that historically served enslaved <strong>and</strong> free Blacks,no longer exist today. Some of those that were closed by colonial authorities were later allowed toreopen. However, Black culture aga<strong>in</strong> became a flashpo<strong>in</strong>t for racial fears after Cuban <strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>in</strong>the early twentieth century. Many Blacks had fought <strong>in</strong> the liberation army as they saw <strong>in</strong>dependenceas the way to end slavery, <strong>and</strong> perhaps achieve Marti’s vision of a raceless society. However, theirhopes for full <strong>in</strong>clusion were not realized, <strong>and</strong> some Black veterans formed the Partido Independientede Color (the Independent Party of Color) <strong>in</strong> 1908. The authorities reacted by outlaw<strong>in</strong>g parties basedon race or class. The PIC led demonstrations <strong>in</strong> Oriente Prov<strong>in</strong>ce that the press immediately labeleda race war or an armed revolt. The government response was bloody <strong>and</strong> brutal: several thous<strong>and</strong>Blacks (not all of them supporters of the PIC) were killed by soldiers dispatched to “put down” therevolt. Newspapers carried wild reports about Blacks murder<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> rap<strong>in</strong>g Whites, <strong>and</strong> civilianmilitias killed dozens of people throughout the isl<strong>and</strong> who had noth<strong>in</strong>g to do with the protests. 59In this climate, the moderniz<strong>in</strong>g elite launched efforts to wipe out what they saw as backward,savage <strong>and</strong> atavistic elements of Cuban culture. A wave of “witchcraft” scares swept the country <strong>and</strong>Afrocuban religious practitioners were harassed <strong>and</strong> arrested. Several abductions <strong>and</strong> murders ofWhite children were attributed to Black “sorcerers”. The police harassed <strong>and</strong> sometimes arrestedAfrocuban religious practitioners, broke up ceremonies <strong>and</strong> seized religious objects. The cabildosthat managed to survive until the triumph of the Cuban revolution <strong>in</strong> 1959 ironically fell victim to thenew government’s proscription of race-based organizations. S<strong>in</strong>ce the revolution had abolished racialdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ation, the argument went, historically Black organizations were at best an anachronism <strong>and</strong>unnecessary, <strong>and</strong> at worst, divisive <strong>and</strong> racist. Thus most of the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g cabildos were closed. 60The history of Carnival follows a similarly bumpy course. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the f<strong>in</strong>al war of <strong>in</strong>dependence, thecolonial government pre-Lenten Carnival (the “White” carnival) was also suspended, but was re<strong>in</strong>statedby the U.S. occupation government. Blacks dem<strong>and</strong>ed the right to participate <strong>and</strong> eventually weregranted a place, <strong>and</strong> by the early twentieth century the pre-Lenten Carnival comb<strong>in</strong>ed elementsof Black <strong>and</strong> White traditions: White beauty queens on floats (usually with corporate or politicalsponsors) surrounded by Black comparsas. The comparsas, which have been severely under-studied,were highly localized, based <strong>in</strong> the historically Black <strong>and</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g class barrios marg<strong>in</strong>ales (marg<strong>in</strong>alneighborhoods) of Havana, <strong>and</strong> to this day, the competition between them reflects longst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gplace-based identities <strong>and</strong> rivalries. 61 Dur<strong>in</strong>g the political <strong>and</strong> economic turmoil of the 1930s <strong>and</strong> 40scompet<strong>in</strong>g political factions often turned Carnival <strong>in</strong>to a political arena, <strong>and</strong> many popular carnivalsongs (some of which are still sung today) conta<strong>in</strong>ed subtle (or not so subtle) political critique or evencampaign slogans.While much of the nationalist elite saw Black culture as anachronistic <strong>and</strong> atavistic, <strong>in</strong> the 1920s asection of the Cuban <strong>in</strong>telligentsia turned to Afrocuban culture as an authentic source of nationalcultural identity free of foreign <strong>in</strong>fluences. 62 Pioneer<strong>in</strong>g ethnographers like Fern<strong>and</strong>o Ortiz, RóomuloLachatañeré <strong>and</strong> Lydia Cabrera pa<strong>in</strong>stak<strong>in</strong>gly documented Afrocuban cultural <strong>and</strong> religious practices. 6313

<strong>Ethnicity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Race</strong> <strong>in</strong> a Chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong>: A Review JournalOrtiz used his research to lobby for the re<strong>in</strong>statement of the Black comparsas <strong>in</strong> Carnival. 64As was true elsewhere <strong>in</strong> the Caribbean, unstable or dictatorial governments often feared thatboisterous public cultural expressions like Carnival, that brought masses of people <strong>in</strong>to the streets,would give way to someth<strong>in</strong>g more seriously threaten<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the 1950s the dictator FulgencioBatista aga<strong>in</strong> banned Carnival. The cultural fervor of the early years of the Cuban revolution <strong>in</strong>cludedefforts to revive (as well as document) “authentic” popular cultural traditions like Carnival, while<strong>in</strong>fus<strong>in</strong>g them with socialist values. Fidel Castro proclaimed Cuba an “Afro Lat<strong>in</strong>” nation <strong>and</strong> Africanbasedcultural practices <strong>and</strong> religions were revalorized as national patrimony (although as culture<strong>and</strong> not as religion). In the early 1960s the com<strong>and</strong>antes (comm<strong>and</strong>ers) paraded <strong>in</strong> what was billedas “Santiago-style” Carnival; a much-quoted aphorism from Che Guevara describes Cuba’s as a“revolution with pachanga“(or “sw<strong>in</strong>g”).As part of the effort to <strong>in</strong>scribe Carnival <strong>in</strong>to the revolutionary project, dur<strong>in</strong>g the campaign for theten million ton sugarcane harvest <strong>in</strong> the 1970s, the authorities shifted Carnival from February to Julyso as not to <strong>in</strong>terfere with the sugar harvest. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the severe economic crisis <strong>in</strong> the early 1990s thatfollowed the collapse of the Soviet Union, the government cancelled Carnival, <strong>and</strong> then re<strong>in</strong>stated it<strong>in</strong> 1995. 65 By the late 1990s, as part of the government’s efforts to package Cuban culture for touristicconsumption, Carnival was made more “commercial”. Traditional neighborhood-based comparsasalternate with floats bear<strong>in</strong>g dancers from the re-opened Tropicana <strong>and</strong> other cabarets. Althoughthese cabarets are all owned by the State, the floats resemble those from the pre-revolutionarycarnival. All along the Malecón, the seafront drive along which the parade proceeds, there are nowfood <strong>and</strong> beverage kiosks that are open for much of summer, <strong>and</strong> several relatively new cabarets<strong>and</strong> discotheques (<strong>in</strong> hard currency) where people can go for live enterta<strong>in</strong>ment after the Carnivalparades.Carnival is actually not a s<strong>in</strong>gle event but a series of parades <strong>and</strong> competitions (with panels of judgesappo<strong>in</strong>ted by the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Culture) that take place throughout the country over a period of severalweeks. Each municipality is given a specific date for its local Carnival, with the festivities <strong>in</strong> Havana(which usually extend over two or three weekends) as the culm<strong>in</strong>ation.Although Carnival is promoted as someth<strong>in</strong>g that belongs to all Cubans, it is hard to avoid the conclusionthat it is, <strong>in</strong> fact, largely a “Black” th<strong>in</strong>g. Based on my observations of Havana’s Carnival over severalyears, nearly all of the comparsa performers are Black, <strong>and</strong> Blacks are somewhat overrepresented <strong>in</strong>the boisterous crowds that l<strong>in</strong>e the Malecón to watch the parade. Like many Black-identified cultural<strong>and</strong> musical forms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g popular musics like timba <strong>and</strong> reggaetón, many Cubans associateCarnival (<strong>and</strong> the street) with rowd<strong>in</strong>ess, excessive consumption of alcohol, <strong>and</strong> the Cuban equivalentof “slackness”, <strong>and</strong> it is subject to <strong>in</strong>tense polic<strong>in</strong>g. 66The revival of Carnival <strong>and</strong> the “<strong>in</strong>vention” of the Salida de los Cabildos, although directed at somewhatdifferent audiences, are both part of the But this Afrocuban “revival” did not beg<strong>in</strong> after the collapseof the Soviet bloc but has its roots <strong>in</strong> the 1980s. In 1986, the government established Casa de Africa,a comb<strong>in</strong>ation museum <strong>and</strong> research center, to further the work of Fern<strong>and</strong>o Ortiz (<strong>and</strong> house someof the artifacts he had collected). In that same year, dockworker Francisco Moya (popularly knownas “Pancho Qu<strong>in</strong>to”) <strong>and</strong> some of his co-workers formed an “amateur” folkloric group called YorubaAndabo, significant <strong>in</strong> that it revived the use of wooden boxes (cajones), a percussion <strong>in</strong>strument thathad fallen out of use <strong>in</strong> the 1940s. Yoruba Andabo, which eventually ga<strong>in</strong>ed “professional” status, setthe stage for the folkloric “boom” of the 1990s.The push to develop <strong>in</strong>ternational tourism (which <strong>in</strong>cluded a vast historical restoration effort <strong>in</strong> OldHavana) thus overlapped with a modest renewal of scholarship on Afrocuban culture <strong>and</strong>, cautiously,14