Bernar Venet - Art Plural Gallery

Bernar Venet - Art Plural Gallery

Bernar Venet - Art Plural Gallery

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

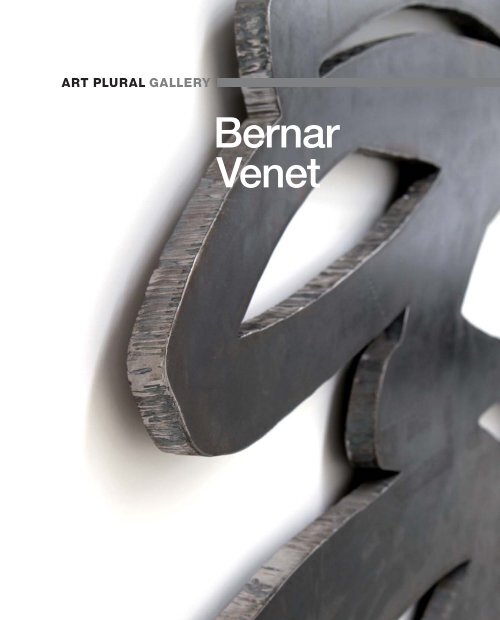

<strong>Bernar</strong><br />

<strong>Venet</strong>

Summary<br />

The Paradox of Coherence 6-37<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection 38-97<br />

Early Wall Reliefs 39-45<br />

Recent Wall Reliefs: GRIBS 46-63<br />

Paintings: Saturations and Shaped Canvases 64-97<br />

Curriculum Vitae 98-110<br />

Acknowledgements 111<br />

3

Portrait of <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, 2011<br />

4 5

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong>istic production can only result from curious, open thought. It functions as a system whose richness consists of<br />

accepting, at one and the same time, the principles of harmony and conflict. It is the competition between those<br />

two elements or givens that creates a whole; and thus the principle of anti-organization becomes a factor in the<br />

development, the indispensable dynamism of the creative process.<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, 1976 1<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> has earned world fame as a sculptor of monumental art, but he began as a painter. Today he makes<br />

both paintings and sculptures which have their deep roots in an analytic program he began as a very young artist<br />

determined to escape the existing models and to formulate a radical art based on geometric theorems and the<br />

graphic imagery of mathematical formulas. As an inquisitive teenager he frequented the record store of the legendary<br />

“Ben”, the Fluxus artist Ben Vautier who drove around in a bus covered with anti art graffiti slogans and was<br />

a reference point for the international avant-garde.<br />

Through Ben, the precocious <strong>Venet</strong> met the Fluxus artists George Maciunas, Robert Filliou and George Brecht<br />

whose work he appreciated but found too close to Dada. Ben also introduced him to the group of avant-garde<br />

artists like Arman, César, Yves Klein and the German “Zero” group who were challenging the high modernist abstraction<br />

practiced in Paris. Although the assemblage artists Pierre Restany promoted as the Nouveaux réalistes<br />

became his friends, <strong>Venet</strong>’s natural inclination was to align himself with the more austere and intellectual monochrome<br />

artists, rather than with the assemblage aesthetic of the Nouveaux réalistes.<br />

Ben remembered <strong>Venet</strong> as a young soldier already experimenting with radical art. (<strong>Venet</strong> was drafted in 1961, sent<br />

to Tarascon and later, as the war was winding down, to Algeria). During a furlough from the army he visited Ben,<br />

announcing he was the fastest painter in the world. “I take five sheets of paper, lay them down side by side on the<br />

floor, take a bottle of ink and spatter all five in a tenth of a second with a single sweep of my arm. That makes two<br />

one hundredths of a second for each one. Nobody’s faster than I am!” 2 .<br />

The spontaneous execution of these paintings could be considered a performance and indeed <strong>Venet</strong> became<br />

increasingly interested in actions documented by photography. In 1961 he started working with trash, poor materials<br />

that anticipated arte povera, rescued from garbage cans. The “trash” paintings, which recorded not an image<br />

but a process, were made by spilling paint on the cardboard panels allowing gravity to determine the direction<br />

and form of the image.<br />

1 <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> remarks, “Published for the first time in the catalogue of my exhibition at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong> during the fall<br />

of 1976, this text is a virtual manifesto, announcing my return to artistic activity and the necessity of being in a permanent and rigorous state<br />

of questioning.” Lawrence Alloway and Thierry Kuntzel. <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, La Jolla Museum of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, La Jolla, California, USA, 1976.<br />

2 Ben tells this anecdote in the 1977 catalogue on the Ecole de Nice by Ben Vautier, Maurice Eschapasse, Nathalie Brunet, Musée national d’art<br />

moderne, CNAC Georges Pompidou, Paris, France, 1977.<br />

7

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> in his studio on rue Parolière,<br />

Nice, 1965<br />

A committed experimenter, <strong>Venet</strong> had already rejected the idea that art transformed matter or that it depended on<br />

the relationship of shapes to one another. Once again emphasizing process over image, in 1963, in the first work<br />

he made as a professional artist, <strong>Venet</strong> claimed as a sculpture a heap of charcoal whose form changed every time<br />

it was dumped on the floor and exhibited. Both the specificity as well as the informal unpremeditated organization<br />

of the material predict the deconstructed elements of arte povera as well as post-minimalist anti-form.<br />

The 1963 Heap of Coal was intentionally inexpressive. In the tar paintings of the early Sixties, <strong>Venet</strong> dispensed<br />

with color and texture. He used tar as a medium because it was free and available but also to avoid oil paint,<br />

which is expressive of the hand of the artist. He termed the built up layers of tar painted on cardboard “industrial<br />

paintings” because of their standardized surfaces, which nevertheless do not look mechanical, geometric or programmatic.<br />

Thus even at the outset of his career, paradox and a sense of contradiction characterizes <strong>Venet</strong>’s art.<br />

This effacement of his own hand is typical of all of <strong>Venet</strong>’s works from the beginning until the present. It was a<br />

choice made not because he lacked technical facility but rather to remove himself from his work. The Constructivists<br />

were the first to wish to create impersonal art that effaced the personality and emotions of the artists in favor<br />

of universality and generalization. Yet we know a lot about the lives of these Russian and Eastern European artists<br />

who dedicated themselves to geometry and strict theories that inspired Mondrian and later non-objective artists.<br />

But none managed to so completely efface their own personalities as totally as <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, who thoroughly<br />

erased his feelings and private life from his work to the extent that critics and historians have been turned into<br />

archeologists in order to reconstruct his evolution as an artist.<br />

PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST<br />

Scraps [Déchets] 1961<br />

Industrial paint on cardboard<br />

Exhibition: Kunsthalle Mücsarnok, Budapest, Hungary, 2012<br />

Creation is first and foremost a historic fact. This does not mean it should be understood as a simple mechanical<br />

relationship between cause and effect, for artistic creation is a function of social milieu, personal biography, the<br />

subjective life of the artist, technical and economic resources, and many other things.<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, 1975 3<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> was born during World War II in Saint-Auban, a provincial manufacturing town in the northern alpine<br />

region of Provence. He was a very precocious child who copied Rembrandt drawings with such obvious artistic<br />

talent that he was invited to exhibit his first oil paintings in the Salon de Peinture de Péchiney in Paris when he was<br />

eleven years old. The youngest of four boys, <strong>Bernar</strong> was drawn not to science like his chemist father, who died<br />

when he was fourteen, or engineering like his brother but to art, an interest his mother encouraged.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> was a quiet intellectual bespectacled boy, by French standards very skinny and very tall. He dreamed of<br />

being a cowboy in America named “Jimmy”, possibly because the image of James Stewart as the gentle lone<br />

3 Originally released as “A Summary of Responses to Basic Questions” from 1975, it was published in <strong>Art</strong>: A Matter of Context. <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>:<br />

Writings 1975-2003. Hard Press Editions, Lenox, Massachussetts, USA, 2004.<br />

Représentation graphique<br />

de la fonction y = -x²/4 1966<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

146 x 121 cm<br />

Collection: Musée National d’<strong>Art</strong> Moderne,<br />

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France<br />

cowboy suggested freedom and adventure. Eventually he would find both in his own nonconformity. But first he<br />

would need to reconcile the two opposing elements of his personality: intellectual introspection and physical action<br />

often expressed in a love of speed and spontaneity fighting against the periods of concentration and analysis<br />

during which his premises are worked out.<br />

Recent investigations have found that the most highly creative and original artists suffer from various childhood illnesses<br />

and traumas that take them away from normal physical activities and provoke episodes of depression during<br />

which mental activity supplants the normal physical outlets of children and adolescents 4 . <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> was no<br />

exception. As a child he suffered from debilitating asthma attacks that kept him out of school and indoors with time<br />

to think, read and reflect. Like Jasper Johns he is an auto-didact with no university education who attended a small<br />

art school only briefly. What he learned he taught himself in his quest for self-education motivated by a voracious<br />

intellectual curiosity.<br />

Before he could move forward, however, <strong>Venet</strong> had to resolve an existential crisis that caused him to think of the art<br />

of the past as a prison from which he had to be freed. In 1959 he produced a series of small paintings that he exhibited<br />

in Saint-Auban before leaving for the army. In Life is a Furlough from Death, 1959 a tiny figure inspired by the<br />

graphic symbols of Paul Klee enclosed in a square within a receding square looks as lost as a character in a Beckett<br />

play. The work was painted in Nice while <strong>Venet</strong> was working as stage designer at the opera. At the time he was fascinated<br />

by the mystery of symbols painted works titled Tomb, Life, Identity and Christ on the Cross… Given his future<br />

development one can imagine that this period of late adolescence coincided with an existential crisis of faith. He<br />

had symbolically painted himself into a corner, Sartre’s Huit clos from which he had to find an exit in order to survive.<br />

THE SEARCH FOR ZERO DEGREE ART<br />

Equations 1966-7<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Exhibition: Kunsthalle Mücsarnok, Budapest, Hungary, 2012<br />

I reject all personal emotion translated onto canvas; we live in an age where industry has taken over… I think everything<br />

can be reduced to graphs, which have no place for spirit and emotion. Development can only come about<br />

through logic: this is why I have taken my art in the direction of logic, which relies a great deal on discipline.<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, 1967 5<br />

In his influential essay The Death of the Author, Roland Barthes continued his description of what he termed the<br />

“degree zero of literature”. This degree zero would mean a new beginning of a neutral art of surface free of emotional<br />

content and distanced from its creator. This was the course <strong>Venet</strong> decided to pursue in redefining painting as an<br />

intellectual activity. Today, <strong>Venet</strong> is world famous for his immense gravity defying steel structures that challenge the<br />

scale of architecture. Less known but essential to the full trajectory of his thinking are his paintings whose images<br />

are taken from mathematical formulas.<br />

4 Schildkraut, et.al. Miró and Spirituality. Wylie, New York, USA, 1992.<br />

5 Besson, Christian, “Transparency and Opacity: The Work of <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> from 1961 to 1976”, <strong>Art</strong>: A Matter of Context. <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>: Writings<br />

1975-2003. Hard Press Editions, Lenox, Massachusetts, USA, 2004.<br />

8 9

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Foreground: Pile of Coal, 1963, sculpture with no specific dimensions<br />

Background: Goudrons [Tars], 1963, tar on canvas, 150 x 130 cm, each<br />

Exhibition: Mücsarnok Kunsthalle, Budapest, Hungary, 2012<br />

10 11

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> in his studio on West Broadway, New York, 1978 Indeterminate Surface 1996<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

253 x 227 x 3.5 cm<br />

Collection: Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> refused any metaphorical reading of the work, a philosophical position aligned with that articulated by<br />

Susan Sontag in her 1963 essay, Against Interpretation. The year Sontag wrote her signature statement, <strong>Venet</strong><br />

moved to his first studio on Rue Pairolière, a working class neighborhood in the old quarter of Nice. By that time<br />

the group of artists from the South of France who became known as the “Ecole de Nice” including Yves Klein<br />

and Arman, had mainly moved to Paris, but <strong>Venet</strong> became their young companion when they returned to party in<br />

sunny Mediterranean port. A generation younger than the Nouveaux réalistes, <strong>Venet</strong> recognized that their break<br />

with the modernist abstraction of the School of Paris was a radical rupture with the past, although alien to his own<br />

austere and analytic vision.<br />

In 1964, <strong>Venet</strong> was invited to show alongside the New Realists and Pop artists in the Salon Comparaisons at the<br />

Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong> in Paris. The works he showed were his folded monochrome reliefs made from crushed<br />

cardboard boxes smashed into rectangles. He continued making cardboard reliefs covering their surfaces with<br />

fresh coats of monochrome industrial paint each time they were exhibited so that they always look fresh and new.<br />

The accumulation of layers of paint unified their now shiny surfaces disguising their humble origins.<br />

As much as <strong>Venet</strong> denies the influence of Marcel Duchamp, who he admired and finally met in 1967, his methods<br />

of investigation and discovery and his search for originality parallel Duchamp’s rejection of formalism and convention<br />

although he never made found objects. Rather he concentrated on found texts. Duchamp held that to think<br />

differently and to make thoroughly original work, the artist needed to go to a country where he did not speak the<br />

language, as Duchamp did during his trip to the Jura Mountains with Apollinaire. <strong>Venet</strong>, easily as French and as<br />

Cartesian as Duchamp, found himself at first mute in New York. He also followed Duchamp’s advice not to take art<br />

but rather mathematics and philosophy as a point of departure. And like Duchamp, he set out to strain the laws<br />

of physics. First of course, he had to learn them.<br />

At this point the ambitious young artist could have settled in Paris, but instead he decided to skip the French<br />

capital and head straight for New York...<br />

NEW YORK, NEW YORK<br />

My purpose was not to dematerialize art, but to stress, through the use of other media that the originality of my<br />

work was in its content, the knowledge it conveyed and its symbolic system - and not in its material characteristics<br />

(or lack thereof).<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, “Ten Years of Conceptual <strong>Art</strong>”, artpress, 1968 6<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> arrived in New York City in April 1966 with a smattering of English and only enough money to call Arman<br />

who was living on the second floor of the tenement where Frank Stella had his studio. Arman was somewhat<br />

shocked to find his young friend had taken him at his word that he would put him up if he ever wanted to come<br />

6 <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, “L’<strong>Art</strong> conceptuel a dix ans,” artpress, n˚ 16, Paris, France, March 1978.<br />

to New York since there was no place to sleep other than his own bed. However, Virginia Dwan was storing her<br />

Kienholz assemblage of a living room in the cramped studio so for two months <strong>Venet</strong> camped out on the red velvet<br />

Victorian couch that was part of the Kienholz tableau.<br />

In 1966, the tenement building at 84 Walker Street was a beehive of activity. Arman, Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean<br />

Tinguely who would become a good friend of <strong>Venet</strong>’s, were living and working on the second floor while Frank Stella<br />

and Carl Andre used the third floor as studios. Although he admired the assemblages of Arman and Cesar, <strong>Venet</strong> was<br />

drawn to their pared down conceptual styles as well as to the intellectual works of Minimalist sculptors such as Dan<br />

Flavin, and particularly Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt who became good friends and with whom <strong>Venet</strong> traded works.<br />

On this first trip to New York in April 1966, the twenty four year old artist stayed only two months. That summer<br />

he turned to Nice and began to study the objectivity of blueprints and the diagrams as possible models for an art<br />

based on semiotics rather than aesthetics.<br />

Realizing his art could only develop in New York, which according to Jean Baudrillard had “stolen the idea of<br />

modern art”, in December <strong>Venet</strong> moved permanently to Manhattan. Before he left Nice, he designed a ballet that<br />

was eventually performed in 1988 by the Paris Opera. The original sketches were related to the diagrams he was<br />

already doing as drawings. The ballet involved a complex arrangement or ropes that held the dancers in space<br />

across the whole of the proscenium. A rootless young vagabond, he often stayed in Arman’s apartment in the<br />

Chelsea Hotel, a meeting place for international artists.<br />

Shortly after his arrival in New York, he exhibited as sculpture a length of industrial cardboard tubing sliced diagonally,<br />

which permitted a simultaneous vision of both its exterior and interior. They depended on the laws of gravity<br />

because the slanted cuts determined their positions. The tube sculptures were made with cardboard rolls and<br />

painted industrial yellow. Others were made out of industrial gray polyvinyl chloride pipes. These sculptures were<br />

empty; their surfaces were visible both from the inside and the outside.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> had already begun making diagrams and he sometimes accompanied this work with a large-scale diagram<br />

of its parts and their construction. This diagram is the prototype of the black and white paintings and drawings<br />

that resembled graphs rather than pictures. He used mathematical formulas rather than text to create a tension<br />

between image and object that was first explored by Fluxus to then become the formula for conceptual art puzzles<br />

that <strong>Venet</strong> ultimately found facile and repetitious.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong>’s decision to work in New York engaged him immediately in the current dialogue on conceptual and performance<br />

art described by Thomas McEvilley. <strong>Venet</strong> wished to avoid the concept of the “aesthetic”, although<br />

as critics have pointed out, in the end even the most radical art can be seen as aesthetic after time passes. His<br />

decision to base his art on the impersonal laws of physics and mathematics was an attempt to free art from the<br />

familiar designed elements of formal compositions.<br />

12 13

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The definition of the work of art as no more than its technical specifications was a direct attack on the idea of art<br />

as spiritual transcendence. <strong>Venet</strong>’s contemporaries in New York were the conceptual artists, but his formation was<br />

quite different from theirs. Whereas they based their explorations on the disjunction between word and image on<br />

the analytic investigations of Ludwig Wittgenstein and the verifiability principle of A.J. Ayer - texts that were available<br />

in English - <strong>Venet</strong> was inspired by the theories of French semiologist Jacques Bertin, at a time when semiotics<br />

was barely known in the United States because the texts had not been translated yet.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> had already been drawing and painting diagrams when Jacques Bertin published his Sémiologie graphique<br />

in 1967, but in Bertin’s theories of linguistics, which defined the three types of visual communication he found a<br />

solid basis for continuing his use of graphic linear formulas as imagery that could not be interpreted any other way,<br />

despite the fact that their context was displaced from textbooks to paintings and later sculpture. In France, Bertin<br />

ran a laboratory where researchers came with drawings for the technical publications. His colleagues noticed that<br />

almost nobody looked at them and even fewer people understood them. This was precisely <strong>Venet</strong>’s aim: to create<br />

a roadblock to interpretation.<br />

In Paris, structuralism was the analytic method of the day. However, among the first to use the term structuralism<br />

in relation to art was the American sculptor and critic Jack Burnham who wrote The Structure of <strong>Art</strong> in 1971. The<br />

title refers to the structure based on linguistic models within a work of art that reveals how content is signified.<br />

Burnham singled out <strong>Venet</strong> as one of the most important practitioners of the structural model in art and reproduced<br />

his photographic enlargement of a page of The Logic of Decision and Action that <strong>Venet</strong> exhibited in 1969.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong>’s selection of the text was not arbitrary: he was searching for a way to base art on logical and rational decisions<br />

that would be the basis for a system 7 . For Burnham, <strong>Venet</strong>’s conceptual work had a double-headed implication.<br />

On the one hand, Burnham wrote, “He is presenting a text which to some extent reveals the constancy of the<br />

structure of art-making. At the same time through the dialectical, and thus historical, progression of knowledge as<br />

an integral aspect of the human condition, he is subverting the historical-mythic structure behind all avant-garde<br />

art.” This was of course exactly <strong>Venet</strong>’s intention.<br />

1969 was a busy year for <strong>Venet</strong>, now an active participant in the New York art world. John Perreault often noted<br />

his activities as part of the downtown avant-garde in his columns in The Village Voice. On May 1, he announced<br />

the Free <strong>Art</strong> Street Works, a group exhibition in which <strong>Venet</strong> participated. Among the participating artists were Vito<br />

Acconci, Scott Burton, Arakawa, and James Lee Byars. In his June 5 column, Perreault reviewed the Para-Visual<br />

Language II exhibition at the Dwan <strong>Gallery</strong> and Lucy Lippard’s <strong>Art</strong> Workers Coalition Benefit at the Paula Cooper<br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> where <strong>Venet</strong> contributed works along with Lawrence Weiner, Sol LeWitt, Bill Bollinger, Robert Smithson,<br />

Mel Bochner, Michael Kirby, Joseph Kosuth, Adrian Piper, On Kawara, Robert Morris, and Bruce Nauman. On<br />

December 18, 1969 Perreault wrote: “I have been receiving The Wall Street Journal every morning courtesy of<br />

7 Jack Burnham, The Structure of <strong>Art</strong>. George Braziller, New York, USA, 1971.<br />

Paintings, 1976-1978, acrylic on canvas<br />

Exhibition: Institut Valencià d’<strong>Art</strong> Modern (IVAM), Valencia, Spain, 2010<br />

14 15

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

9 lignes obliques 2010<br />

Cor-ten steel<br />

H: 30 meters<br />

Installation: Place Sulzer, Promenade des Anglais, Nice, France<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>. Stock market figures and weather reports have been <strong>Venet</strong>’s special thing for a while now, so I<br />

guess this is a work of art.”<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> photographically enlarged pages of stock market quotes as well as other pages taken from printed sources<br />

to mural scale size, which he showed in various exhibitions in the late Sixties. <strong>Venet</strong>’s development reflected both<br />

the French as well as the American approach to post minimal art. The French part of <strong>Venet</strong>’s aesthetic derives<br />

from his knowledge of semiotics and concrete art as it developed in Europe in the forms of musique concrète<br />

and concrete poetry. Indeed, <strong>Venet</strong> has created a concrete music composition recording the sound of the motors<br />

of the supersonic Concorde airplane as well as publishing a provocative volume of concrete poetry that consists<br />

of provocative lists and phrases. Because of his divergent dual background <strong>Venet</strong>’s work predicted rather than<br />

participating in the “dematerialization” of the art object that characterized post minimal and conceptual art in New<br />

York around 1970.<br />

Up to that time he had not in fact concentrated on making objects. In her seminal book on art in the late sixties,<br />

The Dematerialization of the <strong>Art</strong> Object, Lucy Lippard described how <strong>Venet</strong>’s conceptual works antedated the<br />

disappearance of art as specific object, redefining art as a concept rather than as a thing. Concerning <strong>Bernar</strong><br />

<strong>Venet</strong> she wrote: “<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> decides to present during the next four years: Astrophysics, Nuclear Physics,<br />

Space Sciences, Mathematics by Computation, Meteorology, Stock Market, Mathematics, Psychophysics and<br />

Psycho Chronometry, Sociology and Politics, Mathematical Logic, etc.” She quotes <strong>Venet</strong>’s explanation of how<br />

he proceeded: “For each discipline an authority advised me upon the subjects to be presented: these subjects<br />

were chosen according to their importance… The question was not to make a new object, a new readymade<br />

out of mathematics. I attributed a didactic goal to their presentation. Scientific diagrams were painted, at first by<br />

hand, on large canvases; later (1967) some were accompanied by taped lectures and the paintings became photographic<br />

blowups of texts or diagrams directly from books.”<br />

<strong>Venet</strong>’s activity as a conceptual artist did not go unnoticed. In 1971, Donald Karshan organized a retrospective of<br />

his early work at the New York Cultural Center. With that success in hand, <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> shocked his contemporaries<br />

and decided, at the age of twenty-nine, to stop making art.<br />

16 17

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Three Indeterminate Lines 1994<br />

Rolled steel<br />

272 x 305 x 411.5 cm<br />

Private collection, USA<br />

Exhibition: Sotheby’s at Isleworth, Florida, 2008<br />

18 19

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Wall paintings from the Equation series, site-specific dimensions<br />

Exhibition: Ludwig Museum, Koblenz, Germany, 2002<br />

STOP IN THE NAME OF ART<br />

The conceptual impasse of the “little piece of typewritten paper” is a cliché that has had its day. It, too, became<br />

a new aesthetic, but looking back on it now, we see that its alleged contribution wasn’t that much to begin with.<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, “Ten Years of Conceptual <strong>Art</strong>”, artpress, 1968 8<br />

When he moved to New York in late 1966, <strong>Venet</strong> set himself a program of investigation that he definitely intended<br />

to complete. Four years later, he decided that the conceptual phase of his work was over and that he would stop<br />

making art. It was a decision parallel to Duchamp’s refusal to paint after he completed Tu m’ in 1918, which was<br />

an inventory of every conceivable type of illusion painting could produce. Instead of exhibiting, Duchamp worked<br />

in secret for five years producing The Large Glass, the result of his investigations into physics and optics. <strong>Venet</strong><br />

would follow a similar path, disappearing from view.<br />

Returning to Paris, he taught art theory at the Sorbonne and concentrated on writing and thinking without producing<br />

art between 1971 and 1976. The process of finding his own vocabulary was both lengthy and arduous.<br />

The intentional caesura created by <strong>Venet</strong>’s decision to return to France, abandon art making and remove himself<br />

from the New York scene for many years effaced his first New York period of conceptual art and mathematical<br />

and semiotic investigations.<br />

In September 1976, his period of reflection and self-investigation over and bored by inactivity, <strong>Venet</strong> decided to<br />

start making art again and moved back to New York. He acquired studios first on West Broadway and then on<br />

Canal Street, where the minimal artists often found modular industrial materials in quantities. Finding himself with<br />

no furniture in his new studio, <strong>Venet</strong> designed simple geometric seating and tables as he had done previously in<br />

1969. They were sent to a fabricator to be made in steel. This was his first experience in large-scale steel fabrication,<br />

again a chance experience determined by necessity that provided a point of departure, this time for sculpture<br />

in three dimensions. Indeed these unornamented geometric steel forms, which had their origin in practical necessity,<br />

could be considered his first large scale sculptures.<br />

Back in New York, <strong>Venet</strong> threw himself into the New York art scene, participating in group shows at Leo Castelli<br />

and Paula Cooper that included the leading American minimal and conceptual artists. Along the way he encountered<br />

and practiced not only minimal and conceptual art but also performance, photography, poetry, music, choreography<br />

and theater design. He was audaciously experimental. Among friends he would practice entertaining<br />

magic tricks such as balancing a garbage can on his chin, a preview of his apparently innate and intuitive sense<br />

of balance that permitted him to make huge sculptures that appear magically balanced. It was his last act before<br />

deciding to start making art again.<br />

8 <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, “L’<strong>Art</strong> conceptuel a dix ans,” artpress, n˚ 16, Paris, France, March 1978.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong>’s search for an irreducible image with a single reading that resisted interpretation lead to an exploration of<br />

lines, arcs and graphic signs in drawings and paintings that lead him to produce these signs in three dimensions<br />

and use them as building blocks for his sculptures. He began with black and white drawings, paintings and reliefs<br />

of graphs or charts of lines, arcs and angles, the basis of the sculptural style he was about to develop. The pared<br />

down black and white 1976 canvases looked like illustrations enlarged from the pages of a geometry text rather<br />

than paintings. By 1978, the measured black lines inscribed on canvas had become equally precise wood reliefs.<br />

In the succeeding sculptures based on the line, the arc and the angle, the mind completes what the eye sees. This<br />

tension between the perceptual and the conceptual has been a modern theme since Cezanne drew his multiple<br />

line incomplete contours. <strong>Venet</strong>’s concern with essences lead him to investigate the conundrum of what a potentially<br />

infinite three-dimensional line could be.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> considers the open tubes in his 1966 conceptual piece his first three-dimensional lines. He continued this<br />

investigation of transforming the one-dimensional graphic symbol into two- and three-dimensional equivalents.<br />

This is a theme he picked up again in 1979 when he began to develop steel sculptures composed of two arcs and<br />

a series of wood reliefs that lead to the three-dimensional sculptures (1983). The elements of the sculptures were<br />

laid out on the floor of his studio to be organized by <strong>Venet</strong> following the linear scribbles he had previously enlarged<br />

into large metal wall reliefs he called “Indeterminate Areas”.<br />

When he made the transition from wood to steel, a new element entered his repertory: the “Indeterminate Line”.<br />

Defined as a linear form that departs from regularity according to no preconceived plan, but rather takes shape<br />

through the artist’s interaction with his material. The first three-dimensional lines were factory made metal rods<br />

that theoretically could be indefinitely extended. Extrapolated into three dimensions the graphic line becomes<br />

free and playful, antic and unpredictable, thus gaining in force what it loses in rationality. The three-dimensional<br />

line becomes dramatic expression of the space penetrated while avoiding the constraints of composition. The<br />

Indeterminate Lines are not mathematically defined but are variable depending on the artist’s decisions which<br />

incorporate chance and acknowledge the mathematical principle of indeterminacy. The various configurations of<br />

Indeterminate Lines <strong>Venet</strong> begun in the 1980s were made by bending and twisting long square rods of steel with<br />

an overhead crane. The coiled spiraling line bears the memory of the struggle between the artist and his obdurate<br />

material.<br />

As Carter Ratcliff was quick to perceive, <strong>Venet</strong>’s tactics were based on oppositions and contradictions, paradoxes<br />

that generated his forms: “This principle of opposition-sculpture against world, art against non-art, is so reliable<br />

that it is easy to overlook the oppositions within his oeuvre” he wrote. “<strong>Venet</strong> advances by going to extremes, one<br />

after the next, systematically.” Ratcliff also noted that many who knew him as a fabricator of large works in metal in<br />

the Eighties and Nineties forgot or never knew about his work as a conceptual artist in New York in the late Sixties.<br />

The Seventies were a period of transition and personal growth for <strong>Venet</strong> within the context of developments<br />

in New York. Among the most important of these developments was the possibility of creating large-scale<br />

20 21

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Saturation 2006<br />

30 x 4.75 m<br />

Installation: Galerie Philippe Séguin, Cour des Comptes, Paris, France<br />

22 23

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

sculpture for public contexts. In 1967, the United States government began a program of art in public places.<br />

Barnett Newman was among the first artists selected to make a public sculpture. Having never done sculpture,<br />

Newman researched the possibilities for creating works on a large scale to be exhibited outdoors. The Broken<br />

Obelisk would be exhibited in front of the Seagram Building in New York City, in a manner that reflects Barnett<br />

Newman’s claim to “declare the space”. And indeed one can imagine that the vertical thrust as well as the use of<br />

cor-ten by Newman in his sculpture set an example for <strong>Venet</strong>. It was an example he could only fulfill, however, by<br />

integrating his life and art.<br />

A NEW LIFE AND NEW HORIZONS<br />

The artist should remain open and be opposed to sectarianism. Naturally, he or she should be aware of everything<br />

that has been conceived within art, but his or her main activity will be to leave the confines of art. The artist should<br />

take interest in the knowledge of others; have openness towards the outside world that will lead to an engagement<br />

in types of work assumed inconceivable before now.<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>. “Le contexte de l’art, l’art du contexte”, artpress, 1996 9<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> has consistently held that life is unpredictable. He could not for example predict that meeting a<br />

beautiful Parisian journalist after an opening in Nice in 1985 would radically alter the course of his life, opening up<br />

possibilities for expression and expansion as well as bringing a joie de vivre he had never previously experienced.<br />

Now he would divide his time between New York and Le Muy, in the countryside near Nice, where he bought a<br />

large property containing an old mill that was gradually converted into a home filled with art he had traded with the<br />

artists he admired. Both a large painting studio as well as a sculpture studio was added to Le Muy.<br />

Public commissions followed that permitted him to elaborate on a large scale his initial premises. Typical of the<br />

Indeterminate Lines is their relationship to the Asian ideogram or calligraphy. The “scribble” of the twisting and<br />

winding pieces has its analogies in handwriting and as divergent as it is from Picasso’s and David Smith’s geometric<br />

“drawing in space”, they nevertheless offer similar openings and transparency that are characteristic of<br />

modernism not found in traditional sculpture. Take for example the extraordinary and impressive 36-foot high Two<br />

Indeterminate Lines he created for La Défense in Paris in 1986 that rhythmically intertwine as if in a tango.<br />

The Indeterminate Line sculptures preserve the trace or evidence of the resistance of the steel to his will to bend it<br />

into eccentric and unpredictable knots and curves adds drama to our perception of the work as based on a given<br />

material or proposition that is altered by the artist’s human physical intervention. The new studio in Le Muy permitted<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> to expand his horizons and to work on an architectural scale that few sculptors, despite the dreams of<br />

Constructivists like Tatlin, have ever been able to realize.<br />

9 Siegelaub, Seth, “The Context of <strong>Art</strong>, <strong>Art</strong> in its Context”, originally published as “69/96 - Avant garde et fin de siècle - le contexte de l’art, l’art<br />

du contexte”, artpress, n˚ 17, Paris, France, 1996.<br />

88.5˚ Arc x 8 2012<br />

Cor-ten steel<br />

H: 27 meters<br />

Collection: Gibbs Farm, New Zealand<br />

24 25

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

37.5˚ Arc 2010<br />

Cor-ten steel<br />

H: 38 meters<br />

Collection: Dongkuk Steel Co. Ltd, Seoul, South Korea<br />

He added to the vocabulary of the Indeterminate Lines the “Arcs”, segments of circles that first appear in his earliest<br />

drawings and paintings. In 1987 he initiated the series of monumental Arcs with the huge 60 x 120 foot Arc<br />

of 124.5˚ commissioned by the French government for the 750th anniversary of Berlin, which now occupies the<br />

Urianaplatz. Like the subsequent multiple arc sculptures, the work is titled in engraved block letters on the surface<br />

with the circumference, usually the number of degrees of the arc, which emphasizes their literal reference uniquely<br />

to themselves. That the inscribed title is a description of the segment of the circle that the arc represents indicates<br />

<strong>Venet</strong>’s insistence on specificity as a definition of the uniqueness of each work of art.<br />

Each of <strong>Venet</strong>’s Arcs is a segment of the circumference of a circle, a concept he explored earlier in drawings and<br />

paintings. Our knowledge that although the full circle is not present is related to the concept of the indeterminate<br />

line whose beginning and end are equally implied without being given. These mental projections from the physical<br />

work add to the complexity of our reaction which necessarily invokes an unknown, not present but implied projection.<br />

In the case of the precariously balanced Arcs we can project the circle from which they are derived, although<br />

their drama lies precisely in their projection of the non finito.<br />

Working within the parameters of the given, <strong>Venet</strong> pushes those boundaries to see how far they can be extended.<br />

The latest large-scale works are increasingly powerful and dense expressions of <strong>Venet</strong>’s chosen medium and<br />

basic forms, which he may now combine and recombine in a variety of permutations. Inevitably the relation to the<br />

landscape affects the structure of the sculpture. Hard steel contrasts with the soft green forms of nature just as<br />

the diagonals and loops of the Indeterminate Lines contradict the cubic volumes of adjacent buildings. The huge<br />

Arcs look as if they could be rocked thus projecting imminent movement. The towering unfinished vertical Arcs<br />

that the mind finishes represent a penetration of space that defies gravity.<br />

The progression from diagrams and formulas to the obdurate physicality of intractable heavy metal thrust the artist<br />

into unknown territories. The actions of chance, the gravity of materials, and the precariousness of equilibrium still<br />

concern him although now he is able to explore their interaction on a colossal scale. Chance determined heaps of<br />

lines are colossal versions of the original Heap of Coal. The looped skeins of the labyrinthine Indeterminate Lines<br />

that cannot be disentangled correspond to our own existential situation as we attempt to understand where the<br />

universe begins and ends. Thus in the end, <strong>Venet</strong> forgoes his initial rejection of metaphor, placing his work not in<br />

the realm of cold calculation but in that of the precarious and unpredictable human condition. Despite the cold<br />

calculations of his earlier work, <strong>Venet</strong> extrapolated his original mathematically based impersonal inexpressiveness<br />

into forms that have become—perhaps unintentionally—increasingly expressive.<br />

As his concepts developed and his technical skill as well as his means to make larger works improved, <strong>Venet</strong>’s<br />

Lines and Arcs became denser and increasingly monumental and imposing. However despite their explicit weightiness<br />

they are never passive or inert. The huge vertical arcs that lead the eye from earth to sky and back are also<br />

suggestive of human relationships which are totally at odds with <strong>Venet</strong>’s initial exclusively intellectual propositions.<br />

The reductivism of inexpressiveness is replaced by the complexity of a variable and suggestive expressiveness<br />

that, however, is not to be confused with the sentimentality and weltschmerz of expressionism.<br />

26 27

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

<strong>Venet</strong>’s sculptures have a directness and immediacy as well as a sense of scale when contrasted with their surrounding<br />

architecture that seems uncannily appropriate. Indeed, part of their allure is a sense that their precarious<br />

equilibrium is some kind of magic trick, the kind of surprise characteristic of his mercurial personality that we are<br />

provoked to understand and yet cannot quite grasp. The reason we cannot, however, is that behind their apparently<br />

simple presentations are decades of thought and experiment that permit the artist to create such astonishing<br />

forms.<br />

As his work progressed, <strong>Venet</strong> became increasingly aware of human inability to impose a predetermined order.<br />

This perception lead him to permit chance to play a role in his art. Thus he began a dialogue between the predetermined<br />

and the indeterminate. He started to incorporate principles of disorganization or randomness in recent<br />

works that in their compositional formlessness—lines, angles or arcs heaped at random—pick up the thread of<br />

indeterminacy announced the original Heap of Coal.<br />

Tracing the course of his career from the “action” of spilling the pile of coal on to the floor and photographing it<br />

as a work of art we see a strategy of oppositions and self-contradictions that challenge the conventional idea of<br />

stylistic evolution. However, as we review <strong>Venet</strong>’s career, we observe that his use of paradox is consistent in his<br />

work in both painting and sculpture. Thus paradox becomes a principle of continuity rather than of rupture. The<br />

problem then becomes how to reconcile the contradictions of paradox with the logic of coherence.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> resolves this problem by depending on the logic of the conclusions he ultimately draws from his original<br />

theses. If these first principles appear self-contradictory or at odds with each other than the wresting of coherence<br />

from paradox becomes a constant struggle, as other elements such as accident and chance are incorporated into<br />

the system of thought. It is a problem that has perplexed logicians and philosophers since Socrates.<br />

In an effort to reconcile the contradictions of paradox into a coherent system <strong>Venet</strong> came across Kurt Gödel’s<br />

Theory of Incompleteness, which proved that any formal system that is rich enough to express arithmetic will have<br />

a proposition which is true yet cannot be proved, which is a paradox. Gödel showed that formal systems strong<br />

enough for arithmetic are either inconsistent or incomplete and that an inconsistent system is worthless since<br />

inconsistent systems allow contradictions. In the end Gödel concluded that even mathematics was clouded by<br />

subjectivity, leaving no grounds for distinguishing between the rational and the irrational.<br />

Gödel reasoned that although it is obvious that a line can be extended infinitely in both directions, no one has<br />

been able to prove it, which may be why <strong>Venet</strong> refers to his lines as “indeterminate” since they can begin or end<br />

wherever the eye decides is their projection. Gödel proved that there are always more things that are true than you<br />

can prove because any system of logic or numbers that mathematicians ever came up with will always rest on at<br />

least a few unprovable assumptions. Thus if incompleteness is true in math, it’s equally true in science or language<br />

and philosophy and art. Logic could not prove the existence or non-existence of God.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> had never been convinced by the strict axioms of logical positivism, which maintained that anything you<br />

could not measure or prove was nonsense. He was far more comfortable with Gödel’s more elastic system in<br />

which faith and reason are not mutually exclusive. Within this system, even if science rests on an assumption that<br />

the universe is orderly, logical and mathematical based on fixed discoverable laws, you cannot prove it because of<br />

the subjectivity of the human observer. Therefore what you cannot prove you must take on faith based on experience.<br />

And it was precisely experiences, especially new experiences, that <strong>Venet</strong> always sought.<br />

FROM AXIOMATIC PROGRAMS TO THE FREEDOM OF DOUBT<br />

I work in doubt, far from the comfort of the assurance of habit. I paint shaped canvases which I can’t justify either.<br />

It is one kind of possible order… I follow my intuition and it seems to me that the result deserves to exist because<br />

of its difference and because I astonish myself. I don’t have one personality; I have several. I want to live change<br />

and to choose among all the possibilities that it seems to me deserve to exist.<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>, in conversation, 2010<br />

A visit to <strong>Venet</strong>’s studios in Le Muy is an opportunity to watch <strong>Venet</strong> in action like a whirling dervish, painting in<br />

the morning, working in the sculpture studio usually in the afternoon, arranging and rearranging the various linear<br />

elements until he is satisfied with the configuration. Currently <strong>Venet</strong> fabricates the elements of the Arcs, Angles<br />

and Indeterminate Lines in a foundry in Hungary. Once the steel elements are shaped they are brought to his factory<br />

near Le Muy in the Var region of southern France where he has one of his studios. (The other is in New York.)<br />

The Arcs are created by rolling cold steel into predetermined segments, although again he may and often will<br />

change the pieces once he has the elements in his studio. The three-dimensional Indeterminate Lines on the other<br />

hand begin as solid rods that he bends with clamps and tongs overhead cranes to twist them into unpremeditated<br />

configurations that inject them with spontaneity and a sense of motion once they are installed. <strong>Venet</strong> has<br />

described his relationship with his material as an interaction he sets into motion but cannot completely control.<br />

At every point the artist himself intervenes in the creation of the large-scale works, which is particularly evident in<br />

the series of Indeterminate Lines that are the opposite of mechanistic, bearing their traces of the struggle of the<br />

sculptor with his medium.<br />

<strong>Venet</strong> does not make preparatory drawings for his sculptures although he continues to make large drawings as<br />

well as paintings as a separate enterprise. There are maquettes for the later works and from smaller versions,<br />

but these are made after the fact or independently rather that to serve as models to be blown up. He sometimes<br />

creates different models choosing the one that best corresponds to the site, changing between the maquettes<br />

and the final work.<br />

28 29

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

219.5˚ Arc x 22 2006<br />

Cor-ten steel<br />

H: 360 cm, diam.: 430 cm; site-specific dimensions<br />

Collection: Capella Hotel, Singapore<br />

30 31

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

In the final decisions that decide the form of the sculptures, <strong>Venet</strong> literally wrestles with his materials. He considers<br />

this intimate physical relationship with tons of steel a game pitting the constraints of the metal against his will to form<br />

it. This physical struggle is at the heart of the Indeterminate Line sculptures. We feel the physicality of the wrestling<br />

match between the artist and his material as a drama of creation. The solid massive steel resists the artist’s wish to<br />

twist it. The resulting configuration corresponds now to no mathematical formula: it is as unpredictable and uncontrollable<br />

as life itself. Thus the artist who began determined to reduce his work to a single meaning may find that experience<br />

denies that possibility. The paradox of coherence is the result of an infinite form of ever evolving complexity.<br />

In 2000, wishing to attempt something new, <strong>Venet</strong> - probably inspired by the Sol LeWitt wall drawing that occupies<br />

a wall of his house - created a series of murals paintings. The mathematical equations that cover their<br />

monochrome surfaces are once borrowed from scientific works drawn in black on brightly colored grounds. These<br />

works were the subject of an article by Donald Kuspit in the New York <strong>Art</strong> Review that caught the attention of Karl<br />

Heinrich Hofmann, a professor of mathematics at the Technische Universität in Darmstadt, Germany.<br />

Hofmann perceived a relationship between <strong>Venet</strong>’s algebraic formulas to Commutative Diagrams 10 . “To a mathematician<br />

it appears that he is partly motivated by an artist’s desire to make the mathematicians’ infatuation with<br />

‘elegance’—certainly an aesthetic category—manifest for the layman” he observed. However, he was somewhat<br />

befuddled by the critic’s interpretation. According to Kuspit, “We are no longer afraid to be ignorant, for the color<br />

allows us to embrace our ignorance as the way to the emotional truth.” Kuspit saw mathematics as the alienness,<br />

an “entry into the emotional depths. What emotional truth? I suggest it is a sexual truth and depth… which at<br />

its deepest establishes an erotic relationship with the spectator. And which in itself re-enacts the sexual union of<br />

opposites. I suggest that <strong>Venet</strong>’s wall paintings do so, without showing its consummation. They are profoundly<br />

sexual in import, on a grand scale that masks their poignancy 11 .”<br />

Befuddled, the mathematician asks himself, “Could it be possible that I have missed out on something?” Not sharing<br />

the critics “orgiastic sentiments” he enjoyed the manner in which mathematical equations were presented in<br />

an aesthetic context. Hofmann remarks the deliberate repositioning and changes of scale of formulas from books<br />

that alters their function converting them into space defining marks aesthetically arranged. Now the signs used<br />

by mathematicians to communicate information are translated into jumbled typographical markings to fill space.<br />

“Mathematicians”, Hofmann noted, “are likely to react and respond immediately; outsiders are probably surprised<br />

if not stunned by the artist’s proposition that tokens of a highly specialized technical language are to be used as<br />

building blocks of a new artistic expression. The element of surprise is calculated. In <strong>Venet</strong>’s work, mathematical<br />

typography is recognized as its own graphical and architectural structure, utilized and elevated artistically in<br />

a twofold fashion: first, by the brilliant monochromatic backgrounds, and second, by the monumental format 12 .”<br />

10 Hofmann, Karl Heinrich, Notes of the American Mathematical Society, June/July 2002.<br />

11 Kuspit, Donald, “<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>’s Wall Paintings”, New York <strong>Art</strong>s Magazine, n˚ 9, New York, September 2003.<br />

12 Hofmann, Karl Heinrich, Notes of the American Mathematical Society, June/July 2002.<br />

The mural paintings were followed by the Saturation series, large-scale canvases that added another degree of<br />

complexity by altering the size and color of the equations on their monochrome fields. Finding pleasure in painting<br />

with materials that did require a physical struggle, <strong>Venet</strong> continues to paint. The most recent series is inspired by<br />

the gilded ceiling of the Cour des Comptes in Paris, a commission that <strong>Venet</strong> won in a competition.<br />

In making the “gold” paintings, <strong>Venet</strong> first decides on the dimensions and shapes of the works, as well as the texts<br />

and equations and their size and placement and paints the gold grounds himself, but admits he does not have the<br />

patience to apply them to the surface of the paintings, a task he leaves to assistants. He makes the paintings out<br />

of a desire for change in order to get away from routine when he does not have any strong new ideas for sculptures.<br />

“I take all liberties. I work from intuition which is complete opposed and contradictory to my mathematical<br />

works of the Sixties in which theory and logic were more important than the pleasure of painting.”<br />

Originally, as we have observed, <strong>Venet</strong> focused on the relationship between the theoretical, the material and the<br />

practical. He based his forms on those of Platonic geometry—the line, the angle and the curve – that he ultimately<br />

extended to a point where they suggested the infinite. Their concreteness and actuality however maintained<br />

specificity so that they invoked neither Kandinsky’s spiritual dimensions nor Mondrian’s equally transcendental<br />

associations with the purity of the geometric.<br />

Despite the cold calculations of his earlier work, <strong>Venet</strong> extrapolated his original mathematically based impersonal<br />

inexpressiveness into forms that have become—perhaps unintentionally—increasingly expressive. These new<br />

gold ground paintings have no theoretical explanation, nor does <strong>Venet</strong> search for one, feeling his new liberty is a<br />

hard won prize. He does not justify the eccentric shapes of the canvases, considering them just one kind of possible<br />

order that permits him to cut off the texts in unexpected and unpredictable ways.<br />

“After painting the saturations of numerous colors”, he explains, “Today my ideal solution is a ‘non color’ which<br />

at the same time is the ideal background like those of the religious paintings of Cimabue. Besides which my first<br />

paintings were blue, red and the green of the paintings of Cimabue on gold grounds. As a very young artist in<br />

1959 and 1960 I painted religious paintings with gold grounds. At the time I rejected color as much as possible 13 .”<br />

In the current series <strong>Venet</strong> delights in the artificiality of gold since it is a color not found in nature. He explains his<br />

attraction to gold on the basis that gold is not a natural but a cultural color associated with religious paintings<br />

and architectural embellishment. And of course the imagery of mathematics is not that of religious iconography.<br />

Despite the whirl of professional activity at Le Muy, because it is in a pastoral setting, there is a great quiet and a<br />

possibility for contemplation listening to the waterfall outside the ancient mill. The library is full of books <strong>Venet</strong> is<br />

constantly consulting and it is not surprising to find that above his bed in the place where a crucifix would normally<br />

be hung is the text of Gödel’s Theory of Incompleteness.<br />

13 <strong>Venet</strong>, in conversation with the author, 2010.<br />

32 33

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

top left:<br />

Effondrement: 225.5˚ Arc x 11 2011<br />

Cor-ten steel<br />

Diam.: 500 cm; site-specific dimensions<br />

bottom left:<br />

Four Indeterminate Lines 2011<br />

Rolled steel<br />

270 x 550 x 320 cm<br />

219.5˚ Arc x 28 2011<br />

Cor-ten steel<br />

H: 400 cm; diam.: 500 cm; site-specific dimensions<br />

Exhibition: Château de Versailles, France, 2011<br />

34 35

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

85.8˚ Arc x 16 2011<br />

Cor-ten steel<br />

H: 22 meters<br />

Exhibition: Place d’Armes, Château de Versailles,<br />

France, 2011<br />

36 37

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Wall reliefs, 1978-1979, graphite on wood<br />

Exhibition: Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Germany, 2007<br />

39

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Position of Four Right Angles 1979<br />

Graphite on wood<br />

Diam.: 210 cm; depth: 5.5-6 cm; dimensions may vary<br />

Position of Two Major Arcs of 287.5˚ Each 1979<br />

Graphite on wood<br />

Diam.: 210 cm; depth: 5.5-6 cm; dimensions may vary<br />

40 41

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Indeterminate Line 1981<br />

Graphite on wood<br />

189 x 189 cm<br />

42<br />

43

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Indeterminate Line 1984<br />

Graphite on wood<br />

177 x 195 cm<br />

44 45

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Installation of GRIBS in the artist’s studio, 2011<br />

46 47

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

GRIB 5 2011<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

236 x 150 x 3.5 cm<br />

GRIB 1 2011<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

225 x 215 x 3.5 cm<br />

48 49

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

GRIB 1 2011<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

225 x 215 x 3.5 cm<br />

GRIB 1 2011<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

245 x 310 x 3.5 cm<br />

50 51

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Foreground: Six Leaning Straight Lines 2009-2012, cor-ten steel, H: 185 cm; L: 12 meters<br />

Background: GRIB 2 2011, torch-cut waxed steel, 239 x 277 x 3.5 cm - GRIB 2 2011, torch-cut waxed steel, 246 x 240 x 3.5 cm<br />

Exhibition: Kunsthalle Mücsarnok, Budapest, Hungary, 2012<br />

52 53

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

GRIB 3 2011<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

238 x 410 x 3.5 cm<br />

54 55

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Installation of GRIBS in the artist’s studio, 2011<br />

56 57

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

GRIBS, 2011, torch-cut waxed steel<br />

Exhibition: Kunsthalle Mücsarnok, Budapest, Hungary, 2012<br />

58 59

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

GRIB 1 2012<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

248 x 146 x 3.5 cm<br />

GRIB 1 2012<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

249 x 150 x 3.5 cm<br />

60 61

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

GRIB 4 2011<br />

Torch-cut waxed steel<br />

233 x 461 x 3.5 cm<br />

62 63

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Saturations, 2006-2011, acrylic on canvas<br />

Exhibition: Retrospective exhibition at the Kunsthalle Mücsarnok, Budapest, Hungary, 2012<br />

64 65

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Saturation with a Large Bracket 2006<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

200 x 200 cm<br />

66 67

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Gold Saturation with Four Blue Arrows 2008<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

200 x 200 cm<br />

68 69

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Gold Saturation with four Q 2008<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

200 x 200 cm<br />

70 71

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Saturations, 2010-2011, Acrylic on canvas, 80 x 80 cm, each<br />

Exhibition: L’oeuvre peinte, Hôtel des <strong>Art</strong>s, Toulon, France, 2011<br />

72 73

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Gold Saturation with Horizontal Arrow 2011<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

80 x 80 cm<br />

Copper painting with ‘the’ in the upper left corner 2010<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

80 x 80 cm<br />

74 75

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Copper painting with ‘Phi and two 2 2010<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

80 x 80 cm<br />

Gold saturation painting with ‘three integrals’ 2010<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

80 x 80 cm<br />

76 77

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Gold saturation with a big 3 2011<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

80 x 80 cm<br />

Copper painting with ‘Sum W 2’ 2010<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

80 x 80 cm<br />

78 79

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Copper painting with four ‘sums’ 2010<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

80 x 80 cm<br />

Gold saturation painting with ‘a probability densi...’ 2010<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

80 x 80 cm<br />

80 81

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Red and Gold with member function 2009<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

180.5 x 211.5 cm<br />

82 83

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Square Gold with 4 Triangles 2009<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

186.5 x 186.5 cm<br />

84 85

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Peintures or en 4 parties avec ‘contient’ en haut à gauche 2009<br />

[Gold Painting in 4 parts with ‘contient’ on the upper left]<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

213.5 x 333 cm<br />

86 87

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Gold Saturation with ‘we determine finitely’ 2009<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Diam.: 247 cm<br />

88 89

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Double Leaning Gold 2010<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

214 x 313.5 cm<br />

90 91

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Gold Saturation with 2 on the upper right 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

182 x 182 cm<br />

92 93

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Pearl Saturation with NN 2008<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

182 x 182 cm<br />

94 95

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Round Saturation (Gold) with 23 on Top 2011<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Diam.: 214.5 cm<br />

96 97

Curriculum Vitae<br />

1941 Born on April 20 in Château-Arnoux, France.<br />

1958 Studies for one year at the Villa Thiole, the municipal art school of the city of Nice.<br />

1959 Employed as a stage designer for the Nice City Opera.<br />

1964 Participates in the Salon comparaisons at the Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong>, Paris.<br />

1966 Creates a ballet, Graduation, to be danced on a vertical plane. Starts making new work based on<br />

the use of mathematical diagrams.<br />

1971 <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> decides, for theoretical reasons, to cease his artistic activities.<br />

1974 Teaches “<strong>Art</strong> and <strong>Art</strong> Theory” at the Sorbonne, Paris. A representative for France at the XIIIth São<br />

Paulo Biennale, Brazil.<br />

1976 Starts creating artistic work again.<br />

1977 Exhibits at Documenta VI, Kassel, Germany.<br />

1978 Participates in the exhibition “From Nature to <strong>Art</strong>. From <strong>Art</strong> to Nature” at the Venice Biennale, Italy.<br />

1979 Awarded a grant from the National Endowment of the <strong>Art</strong>s, Washington, DC.<br />

1984 Starts creating his sculptures at Atelier Marioni, a foundry in the Vosges region of France.<br />

1988 Jean-Louis Martinoty asks <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> to stage his ballet Graduation (conceived in 1966) at the<br />

Paris Opéra. The artist is the author of the music, choreography, set designs and costumes.<br />

Received the 1988 Design Award for his sculpture in front of the World Trade Center in Norfolk,<br />

Virginia.<br />

1989 Awarded the Grand Prix des <strong>Art</strong>s de la Ville de Paris.<br />

1991 Creates several musical compositions including Sound and Resonance at the Studio Miraval, Var,<br />

France. Release of two compact discs on the Circé-Paris label, Gravier/Goudron, 1963, and Acier<br />

roulé E 24-2, 1990.<br />

1993 Invited to participate in the artists’ film festival in Montreal, Canada for his film Rolled Steel XC-10.<br />

1994 Mr. Jacques Chirac, then the Mayor of Paris, invites <strong>Venet</strong> to present twelve sculptures from his<br />

Indeterminate Line series on the Champ de Mars. This exhibition kicks off a world tour of <strong>Venet</strong>’s<br />

sculptures.<br />

1996 Awarded the honor of “Commandeur dans l’ordre des <strong>Art</strong>s et Lettres” by the Minister of Culture in<br />

France. Presentation of the film Lines, directed by Thierry Spitzer, which covers the artist’s complete<br />

œuvre.<br />

1997 Moves to a studio in Chelsea, New York City. Begins a new series of sculptures entitled Arcs x 4 and<br />

Arcs x 5. Becomes a Member of the European Academy of Sciences and <strong>Art</strong>s, based in Salzburg,<br />

Austria.<br />

1998 Travels to China. Invited by the Mayor of Shanghai to participate in the Shanghai International Sculpture<br />

Symposium.<br />

1999 Installation of a public sculpture in the city of Cologne, Germany in honor of the G-8 Summit.<br />

Releases the third version of the film Tarmacadam (from 1963) with Arkadin Productions.<br />

Exhibits at the Musée d’<strong>Art</strong> Moderne et Contemporain in Geneva.<br />

Publishes a compilation of his poetry, Apoétiques 1967-1998.<br />

2000 Exhibits a new series of wall paintings, Major Equations, at central art museums in Rio de Janeiro<br />

and Saõ Paulo, Brazil; Cajarc, France and at MAMCO in Geneva.<br />

A year of important publications: <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong> 1961-1970, a monograph about the young artist by<br />

99

The Paradox of Coherence<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Selection<br />

Curriculum Vitae<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

2000 Robert Morgan; Sursaturation, an original work about reflections on the possibilities of literature;<br />

<strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>: Sculptures & Reliefs, written by Arnauld Pierre; La Conversion du regard, with texts<br />

and interviews from 1975-2000; Global Diagonals.<br />

2001 Éditions Assouline publishes Furniture, with a text by Claude Lorent in conjunction with exhibitions<br />

at the Galerie Rabouan Moussion and at SM’ART (Salon du mobilier et de l’objet design), both in<br />

Paris.<br />

Poetry reading at White Box in New York with Robert Morgan.<br />

Inauguration of the Chapelle Saint-Jean in Château-Arnoux. The stained glass windows and all the<br />

furniture are designed by <strong>Bernar</strong> <strong>Venet</strong>.<br />

Galerie Jérôme de Noirmont in Paris exhibits new series of Equation paintings.<br />

2002 A performance-evening incorporating the artist’s poetry, film and music at the Centre Georges Pompidou,<br />

Paris, France.<br />

Exhibits Indeterminate Line sculptures at the Galerie Academia in Salzburg, Austria, and at Robert<br />

Miller <strong>Gallery</strong> in New York.<br />

Monograph by Thomas McEvilley on the artist’s complete body of work published in French and<br />

German, and a year later in English.<br />

Exhibits Equation and new Saturation paintings at Anthony Grant, Inc., New York.<br />

Traveling sculpture show arrives in the United States. The Fields at <strong>Art</strong> Omi International Sculpture<br />

Park in New York State inaugurates a program of personal exhibitions presenting twelve of the<br />

artist’s sculptures, covering all variations on the theme of the line. The show moves to the Atlantic<br />

Center for the <strong>Art</strong>s in Florida in November.<br />

2003 Seventeen solo exhibitions this year, including a retrospective of his early work from 1961-1963 at<br />

the Hotel des <strong>Art</strong>s, Toulon, France, and Autoportrait at the Musée d’<strong>Art</strong> moderne et d’<strong>Art</strong> contemporain<br />

(MAMAC) in Nice, France.<br />

Exhibits Saturation paintings in France, California and at the <strong>Art</strong> Basel Miami Beach Fair.<br />

L’Yeuse, Paris publishes first book on Equation paintings, written by Donald Kuspit.<br />

Traveling sculpture show makes its way through Europe: in Nice, France; the city of Luxembourg;<br />

Bad Homburg, Germany; Schloss Herberstein, Austria; and in the Jardin des Tuileries, Paris.<br />

2004 Three simultaneous solo exhibitions at locations in New York City, notably the Robert Miller <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

as well as three large-scale sculptures on the Park Avenue Malls.<br />

Publication of <strong>Art</strong>: A Matter of Context, a book of the artist’s writings and interviews spanning 1975-<br />

2003.<br />