Reading the Book of Nature

Reading the Book of Nature - Roosevelt University Sites

Reading the Book of Nature - Roosevelt University Sites

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

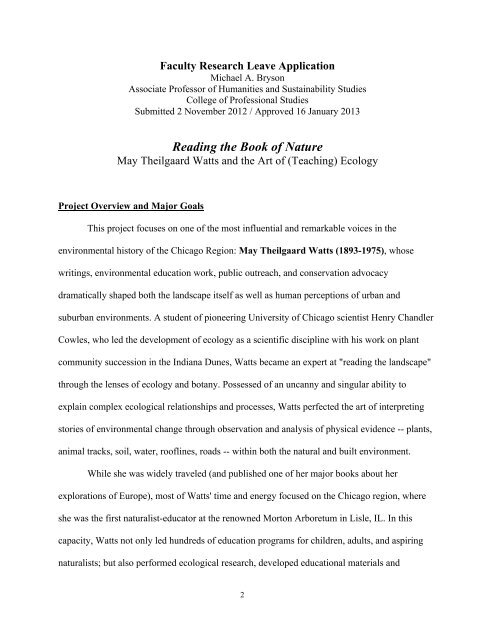

Faculty Research Leave Application<br />

Michael A. Bryson<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Humanities and Sustainability Studies<br />

College <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Studies<br />

Submitted 2 November 2012 / Approved 16 January 2013<br />

<strong>Reading</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Book</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nature</strong><br />

May Theilgaard Watts and <strong>the</strong> Art <strong>of</strong> (Teaching) Ecology<br />

Project Overview and Major Goals<br />

This project focuses on one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most influential and remarkable voices in <strong>the</strong><br />

environmental history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chicago Region: May Theilgaard Watts (1893-1975), whose<br />

writings, environmental education work, public outreach, and conservation advocacy<br />

dramatically shaped both <strong>the</strong> landscape itself as well as human perceptions <strong>of</strong> urban and<br />

suburban environments. A student <strong>of</strong> pioneering University <strong>of</strong> Chicago scientist Henry Chandler<br />

Cowles, who led <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> ecology as a scientific discipline with his work on plant<br />

community succession in <strong>the</strong> Indiana Dunes, Watts became an expert at "reading <strong>the</strong> landscape"<br />

through <strong>the</strong> lenses <strong>of</strong> ecology and botany. Possessed <strong>of</strong> an uncanny and singular ability to<br />

explain complex ecological relationships and processes, Watts perfected <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong> interpreting<br />

stories <strong>of</strong> environmental change through observation and analysis <strong>of</strong> physical evidence -- plants,<br />

animal tracks, soil, water, ro<strong>of</strong>lines, roads -- within both <strong>the</strong> natural and built environment.<br />

While she was widely traveled (and published one <strong>of</strong> her major books about her<br />

explorations <strong>of</strong> Europe), most <strong>of</strong> Watts' time and energy focused on <strong>the</strong> Chicago region, where<br />

she was <strong>the</strong> first naturalist-educator at <strong>the</strong> renowned Morton Arboretum in Lisle, IL. In this<br />

capacity, Watts not only led hundreds <strong>of</strong> education programs for children, adults, and aspiring<br />

naturalists; but also performed ecological research, developed educational materials and<br />

2

curricula, and mentored many fellow educators and nature interpreters who specifically sought<br />

out her expertise. After her retirement, in <strong>the</strong> early 1960s she became <strong>the</strong> chief advocate for what<br />

would be <strong>the</strong> nation's first rails-to-trails conversion project, <strong>the</strong> Illinois Prairie Path -- now one <strong>of</strong><br />

dozens <strong>of</strong> similar recreational trails in and around Chicago, and a model for open space redevelopment<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> US.<br />

Watts' interpretations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> landscape took many forms: drawings, maps, empirical<br />

biological surveys, essays, field guides, newspaper and magazine articles, speeches, and even<br />

public television programs. The most significant and enduring among <strong>the</strong>se is her landmark<br />

book, <strong>Reading</strong> <strong>the</strong> Landscape <strong>of</strong> America, originally published in 1957 and revised by Watts in<br />

1975. This remarkable text combines dozens <strong>of</strong> original illustrations with engaging prose that<br />

despite its explicitly didactic purpose (to teach <strong>the</strong> art and science <strong>of</strong> understanding ecological<br />

relationships and thus "read" <strong>the</strong> history and physical character <strong>of</strong> particular landscapes) is both<br />

entertaining and instructive, scientifically rigorous yet rhetorically artful. Long neglected within<br />

<strong>the</strong> critical context <strong>of</strong> 20 th century American nature writing, <strong>Reading</strong> <strong>the</strong> Landscape <strong>of</strong> America<br />

is, in fact, a watershed book that utilizes art and science in equal measure; explores <strong>the</strong><br />

ecological workings <strong>of</strong> a locale within its environmental and cultural history; recognizes <strong>the</strong><br />

importance <strong>of</strong> native plants in <strong>the</strong> workings <strong>of</strong> ecosystems and <strong>the</strong> identity <strong>of</strong> communities; and<br />

considers both <strong>the</strong> natural and (human) built environments as an integrated whole. Consequently,<br />

Watts' text -- and her multifaceted body <strong>of</strong> work -- are far ahead <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir time, as <strong>the</strong>y articulate<br />

many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ideas and concerns <strong>of</strong> contemporary urban ecology and sustainable development.<br />

The focused study on May Watts previewed here is a vital part <strong>of</strong> my longer-term book<br />

project, Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness, which is a comprehensive and interdisciplinary account<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shape, character, history, and future <strong>of</strong> nature within <strong>the</strong> Chicago metropolitan region.<br />

3

Such a "re-visioning" <strong>of</strong> Chicago -- one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most storied, studied, and celebrated cities in <strong>the</strong><br />

world -- can be realized by figuratively mapping <strong>the</strong> literature and natural history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city onto<br />

<strong>the</strong> spatial contours <strong>of</strong> its geography as well as <strong>the</strong> temporal axis <strong>of</strong> its environmental history.<br />

The literature within this topography is an inclusive category <strong>of</strong> written discourse that<br />

encompasses poetry, fiction, and literary nonfiction; biography and autobiography; nature<br />

writing, scientific reports, and visual art; even planning documents and maps. Defined in this<br />

way, <strong>the</strong> literature <strong>of</strong> nature in <strong>the</strong> Chicago region serves as a useful lens through which to view<br />

<strong>the</strong> environmental changes that have occurred since <strong>the</strong> early days <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city in <strong>the</strong> 1830s, as<br />

well as our shifting attitudes about <strong>the</strong> character and value <strong>of</strong> urban nature in more contemporary<br />

times. Such an assessment is especially timely with <strong>the</strong> recent emergence <strong>of</strong> sustainability as a<br />

conceptual tool for improving <strong>the</strong> environmental quality, economic vitality, and social equity <strong>of</strong><br />

urban regions. The overarching questions that Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness addresses include:<br />

• How does <strong>the</strong> exploration <strong>of</strong> nature within an urban area expand, challenge, and/or<br />

problematize our past and present notions about wilderness? What is at stake in labeling<br />

as "wilderness" particular kinds <strong>of</strong> urban nature, and not o<strong>the</strong>rs?<br />

• What do past and present literary, artistic, and scientific representations <strong>of</strong> nature in<br />

Chicago tell us about <strong>the</strong> character <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> urban environment and our relationship to it?<br />

• How does <strong>the</strong> quality and geographic distribution <strong>of</strong> nature within <strong>the</strong> Chicago region<br />

impact individual neighborhoods and localities, as well as people <strong>of</strong> different classes,<br />

races, and ethnicities?<br />

• How can a new conception <strong>of</strong> urban wilderness provide a framework for addressing<br />

ecological problems and stimulate an appreciation for nature that, in turn, leads to <strong>the</strong><br />

formation <strong>of</strong> beneficial environmental ideas and policies?<br />

• What are <strong>the</strong> necessary elements <strong>of</strong> an urban environmental ethic, and how might a fuller<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> Chicago's ecological and literary histories contribute to its articulation?<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> analytic framework embodied in <strong>the</strong>se questions, my research leave agenda<br />

thus has two concrete goals -- one short-term, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r ongoing. The first is to research, write,<br />

4

and publish <strong>the</strong> first significant critical study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> literary work and public education efforts <strong>of</strong><br />

May Watts, a task which can be tackled within <strong>the</strong> timeframe <strong>of</strong> a one-semester research leave<br />

and which forms a key part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> much larger framework <strong>of</strong> Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness --<br />

specifically, its chapter entitled "City, Suburb, Farm: Chicago <strong>Nature</strong> Writing, Past and Present."<br />

Secondly, in conjunction with <strong>the</strong> research I do for <strong>the</strong> Watts project, I will continue to ga<strong>the</strong>r<br />

and analyze materials, revise <strong>the</strong> organizational framework, and draft sections <strong>of</strong> Mapping <strong>the</strong><br />

Urban Wilderness, since <strong>the</strong>se two research/writing activities are synergistic. The final result will<br />

be a first-<strong>of</strong>-its-kind publishable article on <strong>the</strong> life and work <strong>of</strong> May Watts and significant<br />

progress on my book-length investigation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature and history <strong>of</strong> urban nature in <strong>the</strong><br />

Chicago region.<br />

Significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Research<br />

The ideas, leadership, vision, and influence <strong>of</strong> May Theilgaard Watts made tremendous<br />

impacts upon public environmental attitudes and civic policy here in <strong>the</strong> Chicago region. The<br />

area's environmental history has many o<strong>the</strong>r such examples -- from legendary botanist Henry<br />

Chandler Cowles and landscape architect Jens Jensen in <strong>the</strong> early 20 th century (both <strong>of</strong> whom are<br />

subjects <strong>of</strong> recent biographies) to restoration ecologists Bob Betz and Stephen Packard in more<br />

recent times. Of <strong>the</strong> many people who have influenced <strong>the</strong> direction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chicago region's<br />

environmental movement, though, few have done so more pr<strong>of</strong>oundly than May Watts, who<br />

lived, wrote, and taught during an era <strong>of</strong> rapid suburbanization, ecological degradation, and<br />

political change. By devoting her career to developing what we now might call "ecological<br />

literacy" among her natural history students as well as <strong>the</strong> general public during <strong>the</strong> mid-20 th<br />

century, and by contributing forcefully to <strong>the</strong> land conservation and nascent rails-to-trails<br />

5

movements in <strong>the</strong> 1960s, Watts closely aligned herself with <strong>the</strong> sweeping transformations in <strong>the</strong><br />

nation's environmental attitudes and policies during that tumultuous time, as signaled by <strong>the</strong><br />

publication <strong>of</strong> Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962, <strong>the</strong> first Earth Day in 1970, and <strong>the</strong> passage<br />

<strong>of</strong> landmark environmental legislation (such as <strong>the</strong> Clean Air and Water Acts) in <strong>the</strong> late 60s and<br />

early 70s. Watts thus is a critically important but hi<strong>the</strong>rto unrecognized voice in that<br />

transformative movement, and her life's work -- like that <strong>of</strong> Carson, ano<strong>the</strong>r pioneering female<br />

scientist-writer -- merits both wider recognition and critical scrutiny.<br />

A contemporary assessment <strong>of</strong> Watts' literary/artistic depictions <strong>of</strong> ecology and local<br />

landscapes forms a significant thread within Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness and thus greatly<br />

contributes to our understanding <strong>of</strong> urban ecology, especially that <strong>of</strong> Chicago. The Chicago<br />

region is home to eight million people, numerous endangered species and imperiled habitats <strong>of</strong><br />

both local and global significance, and dozens <strong>of</strong> environmental and scientific groups (from large<br />

institutions to small grass-roots organizations) dedicated to understanding and conserving <strong>the</strong><br />

local environment. My project is thus a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> environmental education and advocacy work<br />

here in <strong>the</strong> Chicago area and, by extension, elsewhere -- efforts that include hands-on studies <strong>of</strong><br />

science and nature in K-12 grades, public outreach programs in wildlife and habitat conservation,<br />

research efforts to document <strong>the</strong> area's biological and ecological diversity, social activism<br />

focused upon achieving environmental justice for all citizens regardless <strong>of</strong> race or location, and<br />

literary/artistic representations <strong>of</strong> urban nature that foster a deeper awareness <strong>of</strong> our place with<br />

<strong>the</strong> natural environment.<br />

This research agenda also relates directly and positively to my teaching within and<br />

directorship <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sustainability Studies Program here at Roosevelt, and consequently to <strong>the</strong><br />

university's mission-driven focus on local outreach to and understanding <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> greater<br />

6

Chicagoland community. My interest in <strong>the</strong> sustainability <strong>of</strong> urban areas has been greatly<br />

influenced by readings <strong>of</strong> naturalists-writers such as Watts, Leonard Dubkin, Jens Jensen, Edwin<br />

Way Teale and o<strong>the</strong>rs who have taken urban areas as <strong>the</strong>ir focus. These authors and o<strong>the</strong>rs like<br />

<strong>the</strong>m cross disciplinary boundaries in fusing art, literature, and science in <strong>the</strong> study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural<br />

environment, and all share a desire to connect with <strong>the</strong> general public as opposed to a narrow,<br />

specialized audience. The interdisciplinary approach to urban nature, perhaps nowhere better<br />

displayed than in <strong>the</strong> writings <strong>of</strong> May Watts, embodies a method and ethos that are explicitly<br />

woven into Roosevelt's Sustainability Studies undergraduate curriculum. Consequently, my<br />

research will augment <strong>the</strong> ways in which our program can develop scientific and environmental<br />

literacy among my students, stimulate awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ecological problems and environmental<br />

impacts <strong>of</strong> urban life, foster appreciation <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong> arts and humanities are just as relevant to<br />

building sustainable communities as are science and policy, and emphasize how local<br />

environmental concerns connect to global issues and trends.<br />

Preliminary Work in Area<br />

My proposed research project is a natural outgrowth <strong>of</strong> my past and current work on <strong>the</strong><br />

relations among scientific discourse, environmental history, urban nature writing, and <strong>the</strong><br />

sustainability <strong>of</strong> cities and suburbs. While I have not done extensive research or writing on May<br />

Watts previously, <strong>the</strong> recent articles I have published on Chicago urban nature writer Leonard<br />

Dubkin and <strong>the</strong> anthropologist, essayist, and poet Loren Eiseley -- as well as <strong>the</strong> contextual<br />

research I've undertaken for Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness -- provide a solid conceptual<br />

framework for an in-depth critical study <strong>of</strong> Watts' life and work. (See <strong>the</strong> Prior Experience<br />

section below for more details on <strong>the</strong>se recently completed projects.)<br />

7

In addition to this research and writing, I have presented widely <strong>the</strong> last five years on<br />

topics such as <strong>the</strong> representation <strong>of</strong> urban wilderness, <strong>the</strong> character <strong>of</strong> nature in cities, urban and<br />

suburban sustainability, water in <strong>the</strong> urban environment, and ecological literacy. All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

concerns have found expression in my scholarly work, popular writings (in newspapers,<br />

magazines, and <strong>the</strong> web), pr<strong>of</strong>essional talks, and public lectures. I thus approach <strong>the</strong> life and<br />

writings <strong>of</strong> May Watts and o<strong>the</strong>r scientist-writers quite differently than I might've, say, ten or<br />

fifteen years ago, when I would've primarily focused on <strong>the</strong> ways in which her writings fuse<br />

literature and science in artful and effective ways. That <strong>the</strong>y do -- but now I'm just as concerned<br />

with how writers like Watts educate <strong>the</strong>ir readers, challenge our assumptions about science and<br />

nature (especially in urban areas), connect with a wide audience, and combine <strong>the</strong>ir artistic<br />

productions with environmental advocacy and conservation work.<br />

Prior Experience in Carrying Out Related Projects<br />

My research and publication record amply demonstrates my capability in planning,<br />

researching, writing, and publishing articles and books similar in scope and approach to <strong>the</strong><br />

projects discussed in this proposal. Of particular note are my two most recent scholarly essay<br />

publications: "Unearthing Urban <strong>Nature</strong>: Loren Eiseley's Explorations <strong>of</strong> City and Suburb"<br />

(2012) and "Empty Lots and Secret Places: Leonard Dubkin's Exploration <strong>of</strong> Urban <strong>Nature</strong> in<br />

Chicago" (2011). Each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se two ecocritical studies assesses how naturalist-writers grapple<br />

with, interpret, and represent <strong>the</strong> various manifestations <strong>of</strong> nature in <strong>the</strong> city; for Eiseley, <strong>the</strong><br />

well-known essayist on matters anthropological and evolutionary, <strong>the</strong> setting was usually New<br />

York or Philadelphia and its suburbs; for Dubkin, <strong>the</strong> now-obscure but once locally notable<br />

naturalist and journalist, it was Chicago. The Dubkin project, one I initiated from scratch during<br />

8

my last research leave (in <strong>the</strong> spring <strong>of</strong> 2007), is <strong>the</strong> most natural precursor to and important<br />

foundation for this proposed study <strong>of</strong> May Watts.<br />

Also relevant here is my 2002 book, Visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Land: Literature, Science, and <strong>the</strong><br />

American Environment from <strong>the</strong> Era <strong>of</strong> Exploration to <strong>the</strong> Age <strong>of</strong> Ecology, a major scholarly<br />

work that was published by <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Virginia Press as part <strong>of</strong> a groundbreaking series<br />

<strong>the</strong>y developed in 2001 entitled "Under <strong>the</strong> Sign <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nature</strong>: Exploration in Ecocriticism."<br />

Visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Land was widely and favorably reviewed in scholarly journals from <strong>the</strong> areas <strong>of</strong><br />

literary studies (American Literature, The New England Quarterly, Great Plains Quarterly,<br />

Rocky Mountain Review), environmental studies (Interdisciplinary Studies <strong>of</strong> Literature and<br />

Environment, Environmental History, H-Environment), and science (ISIS, Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> History<br />

<strong>of</strong> Biology). As literary critic Nina Baym, <strong>the</strong> Swanland Endowed Chair in English at <strong>the</strong><br />

University <strong>of</strong> Illinois, writes in her review for The New England Quarterly,<br />

The texts discussed in Visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Land are not only valuable historical<br />

documents but also strong literary performances in <strong>the</strong>ir own right. The<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> works is original and compelling, and <strong>the</strong> book is commendable<br />

for expanding <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> literary to include a range <strong>of</strong> genres. Its example<br />

may inspire teachers to add Frémont or Powell or, for that matter, Clarence King<br />

or Gifford Pinchot . . . to <strong>the</strong>ir syllabi. And <strong>the</strong>re can be little doubt that <strong>the</strong><br />

chronicle <strong>of</strong> increasing scientific self-awareness and environmental sensitivity<br />

Bryson relates is accurate. But, as Bryson comments ruefully in his afterword, <strong>the</strong><br />

pervasive signs <strong>of</strong> accelerating global degradation are ‘a humbling reminder <strong>of</strong><br />

how far we have to go toward effective environmental stewardship’ (p. 177). It is<br />

perhaps not too much to say that, in detailing how far we have come, Visions <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Land has nudged us one step closer to that goal. (133)<br />

The book also received a citation by CHOICE as a 2003 Outstanding Academic Title publication<br />

in Language and Literature. While not focused on urban areas, contemporary literature, or<br />

Chicago, Visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Land outlines and uses an analytic framework, ecocriticism, that<br />

characterizes my current research practice.<br />

9

Tentative Timeline* for Project Research and Write-up<br />

Date<br />

Before and during<br />

Fall 2013<br />

January 2014<br />

February<br />

March<br />

April<br />

May<br />

June - August<br />

Task<br />

Read and take notes on key primary works by Watts<br />

Compile bibliography <strong>of</strong> relevant primary and secondary works<br />

Identify archival information beyond Morton Arboretum papers<br />

Finish notes on primary texts<br />

Collect and review key sources within secondary literature<br />

Begin archival research at <strong>the</strong> Sterling Morton Library, Morton<br />

Arboretum<br />

Finish notes on secondary literature<br />

Begin outlining article, "<strong>Reading</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Book</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nature</strong>"<br />

Continue archival research at <strong>the</strong> Morton Arboretum<br />

Begin drafting article<br />

Continue archival research at <strong>the</strong> Morton Arboretum<br />

Set up interviews <strong>of</strong> relatives and/or former students <strong>of</strong> Watts<br />

Conduct supporting archival research at <strong>the</strong> Chicago Academy <strong>of</strong><br />

Science (Peggy Notebaert <strong>Nature</strong> Museum), Chicago History<br />

Museum, and Field Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History<br />

Conduct interview <strong>of</strong> relatives and former students/colleagues <strong>of</strong><br />

Watts<br />

Finish first draft <strong>of</strong> article and circulate to colleagues for<br />

comments<br />

Finish archival research at <strong>the</strong> Morton Arboretum<br />

Revise draft based on readers' feedback and additional research<br />

Send out revised article to journal editor(s) for review<br />

* Based on a Spring 2014 Leave<br />

10

Availability <strong>of</strong> Data and Resources<br />

My research project on <strong>the</strong> life and work <strong>of</strong> May Watts presents a unique opportunity to<br />

take advantage <strong>of</strong> an excellent local archival source: <strong>the</strong> Sterling Morton Library at <strong>the</strong> Morton<br />

Arboretum, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> best natural history libraries in <strong>the</strong> Midwest, has her personal papers in its<br />

archive, as well as a deep collection in ecology, natural history, botany, and local history. These<br />

resources are fully available to me as a pr<strong>of</strong>essional scholar through arrangements I have<br />

confirmed with <strong>the</strong> Morton Library. Also available through Arboretum staff and records is<br />

information on former students <strong>of</strong> Watts, some <strong>of</strong> whom are still alive and potentially available<br />

for interviews for my planned biographical research on Watts.<br />

Relationship <strong>of</strong> Work to Developments in <strong>the</strong> Field<br />

Two major areas <strong>of</strong> research and writing intersect within my proposed project: ecological<br />

criticism, or "ecocriticism"; and <strong>the</strong> history, literature, and natural history <strong>of</strong> Chicago. Until quite<br />

recently, ecocritical scholarship has concentrated largely on writers, literary genres, and <strong>the</strong>mes<br />

grounded in remote and rural settings, as opposed to critiquing writers and texts associated with<br />

urban <strong>the</strong>mes and city landscapes. (For a brief definition <strong>of</strong> ecocriticism, see <strong>the</strong> Research<br />

Design and Analytic Methods section below.) In this fashion, since its inception in <strong>the</strong> late 1980s<br />

and early 1990s as a self-described "green" method <strong>of</strong> literary and cultural criticism, ecocriticism<br />

has displayed a bias against <strong>the</strong> urban sphere, though more by benign neglect than conscious<br />

prejudice. In <strong>the</strong> process, ecocriticism lent credence to that age-old opposition <strong>of</strong> nature and<br />

culture by implicitly defining wilderness as, among o<strong>the</strong>r things, that-which-is-not-urban.<br />

Recently, though, <strong>the</strong>re has been a slight shift in <strong>the</strong> winds. For example, critic Michael<br />

Bennett argues for an increased emphasis on urban <strong>the</strong>mes and environments in his 2001 essay,<br />

11

"From Wide Open Spaces to Metropolitan Spaces: The Urban Challenge to Ecocriticism," and<br />

his co-edited collection (with David Teague) <strong>of</strong> urban-centered ecocritical studies, The <strong>Nature</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Cities (1999), sketches an outline <strong>of</strong> how ecocriticism could address urban topics, issues, and<br />

problems. Several years later, <strong>the</strong> urban environment has become a sparsely settled but active<br />

frontier in ecocriticism. Yet, only a few articles and books have applied ecocriticism to urban<br />

subjects (such as John Tallmadge's The Cincinnati Arch); and but for my 2011 publication on<br />

Leonard Dubkin, none take Chicago as its focus. My focus on May Watts as well as <strong>the</strong> wider<br />

context <strong>of</strong> Chicago's urban nature will continue to help expanding <strong>the</strong> ecocritical agenda to urban<br />

subjects in coming years.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r relevant area <strong>of</strong> scholarship is what I've come to call "Chicago Studies" for lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> an <strong>of</strong>ficial term -- works <strong>of</strong> literary criticism and biography; history, both political and<br />

environmental); sociology and urban studies; and natural history and science. These four subareas<br />

<strong>of</strong> Chicago Studies represent but a mere taste <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraordinary range and depth <strong>of</strong><br />

research on and writing about <strong>the</strong> Chicago region. They include literary studies such as Clarence<br />

Andrews' Chicago in Story: A Literary History (1982) that primarily focus on canonical authors<br />

and works <strong>of</strong> Chicago-based fiction and poetry, but pay virtually no attention to nature writing or<br />

works with a scientific element. Biographical studies <strong>of</strong> important environmental figures include<br />

Victor Cassidy's Henry Chandler Cowles: Pioneering Ecologist (2007) and Robert Grese's Jens<br />

Jensen: Maker <strong>of</strong> Natural Parks and Gardens (1998).<br />

Chicago has inspired a wealth <strong>of</strong> influential historical studies, from Milo Milton Quaife's<br />

and Bessie Louise Pierce's comprehensive histories published in <strong>the</strong> early decades <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 20th<br />

century, to more recent works such as William Cronon's <strong>Nature</strong>'s Metropolis: Chicago and <strong>the</strong><br />

Great West (1991), Donald Miller's City <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Century: The Epic <strong>of</strong> Chicago and <strong>the</strong> Making <strong>of</strong><br />

12

America (1996), and <strong>the</strong> magisterial Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Chicago (2004). With <strong>the</strong> notable exception<br />

<strong>of</strong> Cronon's work, though, none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se portray <strong>the</strong> natural environment as a central character in<br />

<strong>the</strong> historical drama, highlighting instead <strong>the</strong> various political, social, and economic forces that<br />

have shaped Chicago's development and identity.<br />

Scholars working in <strong>the</strong> interdisciplinary field <strong>of</strong> urban studies -- who draw insights from<br />

sociology, political science, history, cultural geography, and o<strong>the</strong>r fields -- have produced a<br />

wide range <strong>of</strong> Chicago-based work. Recent examples include Sylvia Washington's Packing Them<br />

In: An Archeaology <strong>of</strong> Environmental Racism in Chicago, 1865-1954 (2005), which takes a<br />

comprehensive look from an environmental policy and social justice perspective at <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong><br />

industrialization, pollution, and hazardous waste on immigrant groups and minority populations<br />

in <strong>the</strong> city; John Hudson's recent geographic syn<strong>the</strong>sis Chicago: A Geography <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> City and Its<br />

Region (2006); and Larry Bennett's assessment <strong>of</strong> Chicago's emergent identity as a postindustrial,<br />

global metropolis in <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> redefining what it means to be a modern city, The<br />

Third City: Chicago and American Urbanism (2010).<br />

Finally, relevant works <strong>of</strong> natural history and science focused on <strong>the</strong> Chicago region<br />

include Joel Greenberg's remarkable environmental history, A Natural History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chicago<br />

Region (2003) and his edited anthology <strong>of</strong> nature writing, Of Prairie, Woods, and Water (2008);<br />

Libby Hill's The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History (2000); <strong>the</strong> Chicago<br />

Wilderness Atlas <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity, now in its 2 nd edition (2011); and Floyd Swink's and Gerould<br />

Wilhelm's botanical classic Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chicago Region (4 th edition, 1994).<br />

My proposed research project is unique and timely because it applies an ecocritical<br />

perspective to an urban subject -- in this case, an important, influential, and heret<strong>of</strong>ore criticallyneglected<br />

writer and naturalist, May Watts; situates <strong>the</strong> study <strong>of</strong> Watt's literary and artistic<br />

13

productions within <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> Chicago's environmental history and future sustainability; and<br />

builds upon and extends current ecocritical scholarship by syn<strong>the</strong>sizing environmental history,<br />

science and natural history, and literary studies. The larger project <strong>of</strong> which <strong>the</strong> Watts study is a<br />

part -- namely, Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness -- integrates what has been up to now separate<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> Chicago Studies, while at <strong>the</strong> same time pushing <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> ecocriticism in an exciting<br />

and fruitful new direction.<br />

Research Design and Analytical Methods<br />

As an interdisciplinary-minded literary critic, my research approach is unabashedly<br />

qualitative. I emphasize <strong>the</strong> close reading and analysis <strong>of</strong> individual texts, <strong>the</strong>ir relationships with<br />

one ano<strong>the</strong>r, and <strong>the</strong>ir place in <strong>the</strong> broad contexts <strong>of</strong> popular scientific discourse, nature writing,<br />

environmental history, and sustainability. I complement this textual approach by firmly<br />

grounding my analyses in <strong>the</strong> appropriate historical context and by situating my interpretations<br />

within <strong>the</strong> relevant secondary literature. My work differs from traditional literary scholarship is<br />

its focus upon non-canonical texts and authors as well as its use <strong>of</strong> insights and <strong>the</strong>ories from<br />

fields such as ecocriticism, <strong>the</strong> cultural study <strong>of</strong> science, and environmental history.<br />

In this project, I strive to bring an "ecologically critical" -- or ecocritical -- perspective to<br />

bear upon <strong>the</strong> life, literary/artistic achievements, public education efforts, and conservation work<br />

<strong>of</strong> May Watts. Ecocriticism is a specific approach within <strong>the</strong> broad area <strong>of</strong> humanistic<br />

interpretation, an environmentally-informed method <strong>of</strong> analyzing texts, artworks, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

cultural products. As ecocritic Cheryl Glotfelty explains in her essay, "What Is Ecocriticism?":<br />

Ecocritics and <strong>the</strong>orists ask questions like <strong>the</strong> following: How is nature<br />

represented in this sonnet? What role does <strong>the</strong> physical setting play in <strong>the</strong> plot <strong>of</strong><br />

this novel? Are <strong>the</strong> values expressed in this play consistent with ecological<br />

wisdom? How do our metaphors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> land influence <strong>the</strong> way we treat it? How<br />

14

can we characterize nature writing as a genre? . . . How has <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong><br />

wilderness changed over time? In what ways and to what effect is <strong>the</strong><br />

environmental crisis seeping into contemporary literature and popular culture?<br />

What view <strong>of</strong> nature informs U.S. government reports, and what rhetoric enforces<br />

this view? What bearing might <strong>the</strong> science <strong>of</strong> ecology have on literary studies?<br />

How is science itself open to literary analysis? What cross-fertilization is possible<br />

between literary studies and environmental discourse in related disciplines such as<br />

history, philosophy, psychology, art history, and ethics?<br />

Glotfelty's free-ranging list <strong>of</strong> critical questions point out, among o<strong>the</strong>r things, <strong>the</strong><br />

interdisciplinary nature as well as <strong>the</strong> activist orientation <strong>of</strong> ecocriticism. This critical approach is<br />

politically and methodologically heterogeneous, but starts from <strong>the</strong> premises that <strong>the</strong> physical<br />

environment is a worthy and important object <strong>of</strong> study; that natural resources are imperiled and<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore in need <strong>of</strong> protection and conservation; and that humanistic inquiry about <strong>the</strong> myriad<br />

relationships between humanity and nature can foster, in <strong>the</strong> long run, ecological awareness and<br />

environmental progress.<br />

15

Appendix A: Outcome <strong>of</strong> Previous Research Leaves<br />

I. "Uniting <strong>Nature</strong>, Science, and Literature: Contemporary Environmental Science<br />

Writers and <strong>the</strong> Inheritance <strong>of</strong> Rachel Carson and Loren Eiseley" (spring 2001) -- The<br />

major goals <strong>of</strong> this study were to analyze contemporary environmental science writers in light <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> nature writing and popular science <strong>of</strong> Rachel Carson and Loren Eiseley; to assess <strong>the</strong><br />

development <strong>of</strong> a new mode <strong>of</strong> environmental science writing which combines elements <strong>of</strong><br />

natural history, travel literature, popular science, biography, and/or autobiography; and to<br />

examine how this discourse (1) vigorously critiques our environmental values and practices, (2)<br />

fosters scientific and environmental literacy among <strong>the</strong> general public, and (3) reflects and/or<br />

revises gendered representations <strong>of</strong> both nature and science.<br />

My work during that 2001 research leave resulted in a peer-reviewed journal article<br />

entitled "It's Worth <strong>the</strong> Risk: Science and Autobiography in Sandra Steingraber's Living<br />

Downstream" published in Women's Studies Quarterly (2001) -- <strong>the</strong> first scholarly study <strong>of</strong><br />

Steingraber, who in subsequent years has become one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most important scientist-writers /<br />

environmental activists in <strong>the</strong> US, as evidenced by her string <strong>of</strong> critically-acclaimed books and<br />

artful journalism. More importantly, I completed <strong>the</strong> final revisions <strong>of</strong> a book manuscript,<br />

Visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Land: Literature, Science, and <strong>the</strong> American Environment, which had been<br />

submitted for review to <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Virginia Press in <strong>the</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> 2000. The book was<br />

formally awarded a contract based on my spring 2001 revisions, and was published in 2002 as<br />

<strong>the</strong> 9th book in <strong>the</strong>ir new environmental studies series, "Under <strong>the</strong> Sign <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nature</strong>." (I should also<br />

note that in <strong>the</strong> summer <strong>of</strong> 1997, a $500 Roosevelt Summer Research Grant supported my early<br />

efforts to reconceptualize and conduct additional research on my PhD dissertation, which in turn<br />

16

provided <strong>the</strong> foundation for Visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Land a few years later.) Thirdly, <strong>the</strong> additional<br />

research I conducted on Rachel Carson and Loren Eiseley during that leave produced a scholarly<br />

article focused on <strong>the</strong>ir scientific rhetoric in a 2003 issue <strong>of</strong> Technical Communication<br />

Quarterly.<br />

II. Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness: An Ecological and Literary Topography <strong>of</strong> Chicago<br />

(spring 2007) -- My second research leave provided me with an exceptional opportunity to<br />

change directions in my research agenda significantly, from a wide-ranging emphasis on scienceand-literature<br />

studies to a new focus on <strong>the</strong> urban environment (particularly Chicago) and citybased<br />

nature writing. The goals <strong>of</strong> this study were to lay <strong>the</strong> initial groundwork for a book<br />

tentatively entitled Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness: An Ecological and Literary Topography <strong>of</strong><br />

Chicago, discussed earlier in this proposal, as well as to write and publish a scholarly essay (<strong>of</strong><br />

30-40 manuscript pages) based on that research that would be suitable for publication as a standalone<br />

article in a notable environmental studies / interdisciplinary journal.<br />

This leave period also was fruitful on multiple fronts. Notably, in <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> my<br />

research for Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness, I unear<strong>the</strong>d some fascinating information on <strong>the</strong><br />

Chicago-based urban nature writer Leonard Dubkin, a self-taught naturalist and journalist who<br />

published a string <strong>of</strong> singular and o<strong>the</strong>rwise remarkable books from <strong>the</strong> mid-1940s to <strong>the</strong> early<br />

1970s about observing nature in Chicago. When I made contact with Dubkin's daughter, who<br />

lives in Chicago and gave me unfettered access to many <strong>of</strong> her personal papers, I knew I had an<br />

extraordinary chance to research and write about a forgotten author, with access to drafts, letters,<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r papers. I was able to capitalize on this work by publishing <strong>the</strong> first scholarly treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> Dubkin's work in <strong>the</strong> leading journal <strong>of</strong> ecocriticism, Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature<br />

17

and Environment. Secondly, during what became an intensely focused period <strong>of</strong> Dubkin<br />

research, I made substantial progress in creating <strong>the</strong> bibliographic and conceptual foundation for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Mapping <strong>the</strong> Urban Wilderness book.<br />

But an unexpected, yet perhaps most important outcome, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shift in research focus<br />

enabled by my 2007 leave was <strong>the</strong> inspiration it provided me to <strong>of</strong>fer an experimental course in<br />

urban sustainability in <strong>the</strong> spring semester <strong>of</strong> 2009. This innovative Chicago-focused<br />

interdisciplinary seminar not only led to ano<strong>the</strong>r peer-reviewed publication (Bryson and Zimring,<br />

"Creating <strong>the</strong> Sustainable City") but also provided <strong>the</strong> foundation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new Sustainability<br />

Studies undergraduate major at RU in <strong>the</strong> 2009-2010 academic year -- a program at <strong>the</strong> forefront<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> university's overall sustainability efforts and now home to 55+ majors.<br />

18

Bibliography<br />

Andrews, Clarence A. Chicago in Story: A Literary History. Iowa City, Iowa: Midwest<br />

Heritage Publishing Co., 1982.<br />

Baym, Nina. "Review <strong>of</strong> Visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Land." The New England Quarterly (March 2003): 130-<br />

3.<br />

Bennett, Larry. The Third City: Chicago and American Urbanism. Chicago: University <strong>of</strong><br />

Chicago Press, 2010.<br />

Bennett, Michael. "From Wide Open Spaces to Metropolitan Places: The Urban Challenge to<br />

Ecocriticism." Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 8.1 (Winter<br />

2001): 31-52.<br />

Bennett, Michael, and David W. Teague, eds. The <strong>Nature</strong> <strong>of</strong> Cities: Ecocriticism and Urban<br />

Environments. Tucson: University <strong>of</strong> Arizona Press, 1999.<br />

Bryson, Michael A. "Empty Lots and Secret Places: Leonard Dubkin's Exploration <strong>of</strong> Urban<br />

<strong>Nature</strong> in Chicago." Interdisciplinary Studies <strong>of</strong> Literature and Environment 18.1 (Winter<br />

2011): 47-66.<br />

-----. "Unearthing Urban <strong>Nature</strong>: Loren Eiseley's Explorations <strong>of</strong> City and Suburb." In Artifacts<br />

and Illuminations: Critical Essays on Loren Eiseley, eds. Tom Lynch and Susan<br />

Maher. Lincoln: University <strong>of</strong> Nebraska Press, 2012. 77-98.<br />

-----. Visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Land: Literature, Science, and <strong>the</strong> American Environment from <strong>the</strong> Era <strong>of</strong><br />

Exploration to <strong>the</strong> Age <strong>of</strong> Ecology. Charlottesville, VA: University <strong>of</strong> Virginia Press,<br />

2002.<br />

Bryson, Michael A. and Carl Zimring. "Creating <strong>the</strong> Sustainable City: Developing an<br />

Interdisciplinary Introduction to Urban Environmental Studies for a General Education<br />

Curriculum." Metropolitan Universities Journal 20.2 (July 2010): 105-116. Special<br />

issue: "The Green Revolution <strong>of</strong> Metropolitan Universities," edited by Roger Munger.<br />

Burnham, Daniel H. and Edward H. Bennett. Plan <strong>of</strong> Chicago. 1909. New York: Da Capo Press,<br />

1970.<br />

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. New York: Houghton-Mifflin, 1962.<br />

Cassidy, Victor. Henry Chandler Cowles: Pioneering Ecologist. Seattle: Kedzie Press, 2007.<br />

Cronon, William. Changes in <strong>the</strong> Land: Indians, Colonists, and <strong>the</strong> Ecology <strong>of</strong> New England.<br />

New York: Hill and Wang, 1983.<br />

-----. <strong>Nature</strong>'s Metropolis: Chicago and <strong>the</strong> Great West. New York: Norton, 1991.<br />

19

Dixon, Terrell, ed. City Wilds: Essays and Stories about Urban <strong>Nature</strong>. A<strong>the</strong>ns: University <strong>of</strong><br />

Georgia Press, 2002.<br />

Dubkin, Leonard. My Secret Places: One Man's Love Affair with <strong>Nature</strong> in <strong>the</strong> City. New York:<br />

David McKay, Inc., 1972.<br />

Glotfelty, Cheryl. "What Is Ecocriticism?" Defining Ecocritical Thought and Practice: Position<br />

Papers from <strong>the</strong> 1994 Western Literature Association Meeting, Salt Lake City, Utah, 6<br />

October 1994. Online. Association for <strong>the</strong> Study <strong>of</strong> Literature and Environment. 1994.<br />

Accessed Nov. 2005. .<br />

Greenberg, Joel. A Natural History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chicago Region. Chicago: University <strong>of</strong> Chicago<br />

Press, 2003.<br />

-----, ed. Of Prairie, Woods, and Water: Two Centuries <strong>of</strong> Chicago <strong>Nature</strong> Writing. Chicago:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 2008.<br />

Grese, Robert. Jens Jensen: Maker <strong>of</strong> Natural Parks and Gardens. Baltimore, MD: Johns<br />

Hopkins University Press, 1998.<br />

Grossman, James R., Ann Durkin Keating, and Janice L. Reiff, eds. The Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong><br />

Chicago. Michael P. Conzen, cartographic editor. Chicago: University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press,<br />

2004.<br />

Hill, Libby. The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History. Chicago: Lake Claremont<br />

Press, 2000.<br />

Miller, Donald L. City <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Century: The Epic <strong>of</strong> Chicago and <strong>the</strong> Making <strong>of</strong> America. New<br />

York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.<br />

Pellow, David Naguib. Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Environmental Justice in Chicago.<br />

Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002.<br />

Pierce, Bessie Louise, ed. As O<strong>the</strong>rs See Chicago: Impressions <strong>of</strong> Visitors, 1673-1933. Chicago:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 1933.<br />

Quaife, Milo Milton. Chicago and <strong>the</strong> Old Northwest, 1673-1835: A Study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Evolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Northwestern Frontier, Toge<strong>the</strong>r with a History <strong>of</strong> Fort Dearborn. Chicago: University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 1913.<br />

-----. Chicago's Highways Old and New: From Indian Trail to Motor Road. Chicago: D. F.<br />

Keller and Co., 1923.<br />

Sullivan, Jerry. An Atlas <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity, revised edition. Chicago: Chicago Wildernes, 2011.<br />

20

-----. Hunting for Frogs on Elston, and O<strong>the</strong>r Tales from Field and Street. Chicago: University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 2004.<br />

Swink, Floyd and Gerould Wilhelm. Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chicago Region. 4th edition. Indianapolis:<br />

Indiana Academy <strong>of</strong> Science, 1994.<br />

Tallmadge, John. The Cincinnati Arch: Learning from <strong>Nature</strong> in <strong>the</strong> City. A<strong>the</strong>ns: University <strong>of</strong><br />

Georgia Press, 2004.<br />

Washington, Sylvia. Packing Them In: An Archaeology <strong>of</strong> Environmental Racism in Chicago,<br />

1865-1954. Lanham: Lexington <strong>Book</strong>s, 2005.<br />

Watts, May T. <strong>Reading</strong> <strong>the</strong> Landscape <strong>of</strong> America. 1957. New York: Macmillan, 1975 (2 nd<br />

edition).<br />

-----. <strong>Reading</strong> <strong>the</strong> Landscape <strong>of</strong> Europe. New York: Harper and Row, 1971.<br />

21