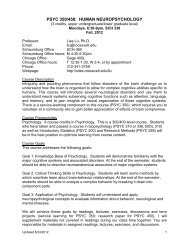

Mothering Violence: Ferocious Female Resistance in Toni ...

Mothering Violence: Ferocious Female Resistance in Toni ...

Mothering Violence: Ferocious Female Resistance in Toni ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Mother<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Violence</strong>: <strong>Ferocious</strong> <strong>Female</strong> <strong>Resistance</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Toni</strong> Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Sula, Beloved, and A<br />

Mercy<br />

Amanda Putnam, Roosevelt University<br />

Abstract<br />

Racially exploited, sexually violated, and often emotionally humiliated for years or<br />

decades, certa<strong>in</strong> black female characters with<strong>in</strong> four of <strong>Toni</strong> Morrison’s novels make<br />

violent choices that are not always easily understandable. The violence—sometimes<br />

verbal, but more frequently physical—is often an attempt to create unique solutions<br />

to avoid further victimization. Thus, violence itself becomes an act of rebellion,<br />

a form of resistance to oppressive power. The choice of violence—often rendered<br />

upon those with<strong>in</strong> their own community and family—redirects powerlessness and<br />

transforms these characters, re-def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g them as compell<strong>in</strong>gly dom<strong>in</strong>ant women.<br />

However, their transformation often has multidimensional repercussions for them<br />

and those with whom they have chosen to be violent.<br />

Black female characters with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Toni</strong> Morrison’s novels are often<br />

scarred—physically and/or emotionally—by the oppressive environments<br />

around them. Racially exploited, sexually violated, and often<br />

emotionally humiliated for years or decades, these women often learn to<br />

coexist with their visible and <strong>in</strong>visible scars by mak<strong>in</strong>g choices that are not<br />

easily understood. Specifically, many of Morrison’s female characters turn<br />

to violence—sometimes verbal but more frequently physical—and, <strong>in</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g<br />

so, attempt to create unique solutions to avoid further victimization. This<br />

process demonstrates the ways <strong>in</strong> which violence itself can become an act<br />

of rebellion, a form of resistance to oppressive power.<br />

Rang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> age from children to adolescents and adults, these female<br />

characters choose violence to f<strong>in</strong>d an escape—a disruption of the multifaceted<br />

oppression they have suffered with<strong>in</strong> a white patriarchal society where<br />

black women are tormented and subjugated by social and racial dom<strong>in</strong>ation,<br />

Black Women, Gender, and Families Fall 2011, Vol. 5, No. 2 pp. 25–43<br />

©2011 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Ill<strong>in</strong>ois

26 amanda putnam<br />

exclusion, and rejection. Their choices of violence—often rendered on those<br />

with<strong>in</strong> their own community or family—redirects that powerlessness and<br />

transforms it. Wreak<strong>in</strong>g havoc on societal expectations for their behavior<br />

and thoughts, these violent actions establish a new vision of African American<br />

fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ity and femaleness. Black women are not powerless or without<br />

options; <strong>in</strong>stead, they can create new patterns and refuse socialized gender<br />

and racial identities that attempt to constra<strong>in</strong> them.<br />

Sometimes their violent choices negatively affect other members of the<br />

African American community <strong>in</strong> which these female characters reside; however,<br />

it reflects the often racially motivated violence of the world around<br />

them. In other words, while the violence may be wasteful or even damag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to <strong>in</strong>dividual psyches and broader communities, it is also a reprojection of<br />

the white oppression that has been forced on their very souls. By tak<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

violence forced on them and redirect<strong>in</strong>g it, these characters redef<strong>in</strong>e themselves<br />

as compell<strong>in</strong>gly dom<strong>in</strong>ant women.<br />

This pattern of violence emerges <strong>in</strong> some dur<strong>in</strong>g early childhood. Realiz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

their own worth is <strong>in</strong> question, young black girls attempt to upset<br />

white oppression by redef<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the limits of their power and powerlessness.<br />

Young black girls react<strong>in</strong>g to the oppressiveness of white dom<strong>in</strong>ance or to the<br />

str<strong>in</strong>gency of traditional female-behavior expectations counter with physical<br />

violence to f<strong>in</strong>d strength with<strong>in</strong> what often are positions of weakness.<br />

Likewise, other black female children react verbally to withstand the force<br />

of ever-present white-societal beauty standards that could otherwise crush<br />

their self-identity.<br />

Most of Morrison’s youthful characters learn about violence with<strong>in</strong> a<br />

matril<strong>in</strong>eal home sett<strong>in</strong>g, when they are exposed to violence toward, and<br />

then from, their mothers and grandmothers. At times enslaved but always<br />

oppressed, these adult women characters are abused frequently by multiple<br />

sources: spouses, parents, employers, slaveowners, and community members.<br />

Consequently, the women’s mistreatment is then redirected toward others—<br />

often children—with<strong>in</strong> the family. While pa<strong>in</strong>ful to absorb, this redirection<br />

can also be seen as an additional mother<strong>in</strong>g lesson—an <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ctive message<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g black children cop<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms with<strong>in</strong> a world that denies and<br />

exploits their self-worth.<br />

Maternal abandonment, either literal or emotional, is one common manifestation<br />

of these lessons <strong>in</strong> Morrison’s texts, often result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> child-driven<br />

violence. Regardless of whether the abandonment is <strong>in</strong>tentional or desired,<br />

the child perception of be<strong>in</strong>g abandoned often drives the child to act out<br />

violently. Disturb<strong>in</strong>g the development of necessary community-based sentiments,<br />

such as empathy or social identification, the mother violence creates

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 27<br />

children (and subsequently adults) who feel detached from others <strong>in</strong> their<br />

community, allow<strong>in</strong>g the twisted familial violence to be perpetuated. Home,<br />

then, becomes a place to learn pa<strong>in</strong>, while community becomes a place to<br />

act it out.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, Morrison establishes child murder as the ultimate form of mother<br />

violence, expos<strong>in</strong>g the complexities of the mother<strong>in</strong>g construct <strong>in</strong> terms of<br />

creation and destruction. By not only decid<strong>in</strong>g on death for their progeny<br />

but also perform<strong>in</strong>g the murder themselves, these black women assert their<br />

motherhood over societal mores. By choos<strong>in</strong>g death for their children, these<br />

mothers claim their motherhood <strong>in</strong> ways that are challeng<strong>in</strong>g to understand—yet,<br />

<strong>in</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g so, these female characters achieve astonish<strong>in</strong>gly powerful<br />

personas.<br />

In The Bluest Eye, n<strong>in</strong>e-year-old Claudia beg<strong>in</strong>s to discover the need<br />

for rebellion when she encounters her <strong>in</strong>visibility <strong>in</strong> popular culture. Her<br />

hatred of white baby dolls beg<strong>in</strong>s with an aversion to a famous white child<br />

star. With an adult-like understand<strong>in</strong>g of the <strong>in</strong>equities that occur daily due<br />

to sk<strong>in</strong> color, Claudia shares her dislike of Shirley Temple, who danced with<br />

Bill “Bojangles” Rob<strong>in</strong>son, a famous black tap dancer, <strong>in</strong> various films: “I<br />

couldn’t jo<strong>in</strong> [Freda and Pecola] <strong>in</strong> their adoration because I hated Shirley.<br />

Not because she was cute, but because she danced with Bojangles, who was my<br />

friend, my uncle, my daddy, and who ought to have been soft-shoe<strong>in</strong>g it and<br />

chuckl<strong>in</strong>g with me” 1 (Morrison 1994, 19). In Claudia’s explanation, it’s clear<br />

that she feels someth<strong>in</strong>g has been stolen from her (and others like her)—and<br />

given to the white child star <strong>in</strong>stead. The performance pair<strong>in</strong>g of the adult<br />

black male and the small white girl highlights the absence of the small black<br />

girl performer—the performer who looked like Claudia. Instead of shar<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the spotlight, the black girl becomes <strong>in</strong>visible, and Claudia’s feel<strong>in</strong>gs of<br />

anger due to that <strong>in</strong>visibility are projected onto Shirley Temple: someone<br />

out of reach and yet with<strong>in</strong> view. Claudia’s feel<strong>in</strong>gs of black <strong>in</strong>visibility are<br />

magnified via the white baby dolls she receives as gifts. By dismember<strong>in</strong>g<br />

them, Claudia disrupts the obsessive desire to worship white/light attributes,<br />

reject<strong>in</strong>g them for her own blackness. She rebels aga<strong>in</strong>st white oppression,<br />

forc<strong>in</strong>g others to see her and not a reflection of whiteness.<br />

The outward violence Claudia feels is not unlike the heartbreak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternal<br />

violence another black girl <strong>in</strong> The Bluest Eye, Pecola, demonstrates aga<strong>in</strong>st<br />

herself for similar reasons. Despised by her mother and ignored by her father,<br />

Pecola is a tragic example of the destructive power of accept<strong>in</strong>g white beauty<br />

standards. Realiz<strong>in</strong>g that the “white immigrant storekeeper” who she is buy<strong>in</strong>g<br />

candy from, shows only “distaste . . . for her, her blackness” (ibid., 48–49),

28 amanda putnam<br />

Pecola accepts a self-hatred and embraces all th<strong>in</strong>gs white: Shirley Temple,<br />

white baby dolls, the white Mary Jane on the candy wrapper, and eventually,<br />

her quest to atta<strong>in</strong> blue eyes. Kathy Russell, Midge Wilson, and Ronald Hall<br />

(1992) discuss the effects of white beauty standards among black children:<br />

“Accord<strong>in</strong>g to psychiatrists William Grier and Price Cobbs, authors of Black<br />

Rage, every American Black girl experiences some degree of shame about her<br />

appearance. Many must submit to pa<strong>in</strong>ful hair-comb<strong>in</strong>g rituals that aim to<br />

make them look, if not more ‘White-like,’ at least more ‘presentable’” (43).<br />

Without argument, Pecola accepts the sham<strong>in</strong>g of her blackness, bow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to (and eventually break<strong>in</strong>g under) the heavy weight of white oppression.<br />

In Morrison’s novels, young black girls, taught by society to worship white<br />

fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ity and white motherhood by the community adoration of them,<br />

must either believe <strong>in</strong> their own deficiencies, as Pecola does, or attack the<br />

source of oppression, as Claudia does.<br />

Thus, some of Morrison’s females resist white beauty ideals by us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

verbal violence to susta<strong>in</strong> a positive self-image. Claudia and Freda use verbal<br />

aggression aga<strong>in</strong>st Maureen Peal, a “high-yellow dream child,” (Morrison<br />

1994, 62), eventually dis<strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to a yell<strong>in</strong>g fight about sk<strong>in</strong> color. 2<br />

Maureen represents yet more devotion to white beauty standards as the lightsk<strong>in</strong>ned,<br />

straight-haired black child who baits a dark-sk<strong>in</strong>ned girl. Grasp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that Maureen is us<strong>in</strong>g “black” as a derogative description (and recogniz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

her own presence with<strong>in</strong> the same category), Claudia’s m<strong>in</strong>dset shifts as<br />

she understands that she is also under attack. The f<strong>in</strong>al <strong>in</strong>sult by Maureen<br />

is used to draw acute awareness of her own highly favored light sk<strong>in</strong> color:<br />

“‘I am cute! And you ugly! Black and ugly black e mos’” (ibid., 73). Claudia<br />

and Freda s<strong>in</strong>k under the wisdom, accuracy, and relevance of Maureen’s last<br />

words:<br />

If she was cute—and if anyth<strong>in</strong>g could be believed, she was—then we were<br />

not. And what did that mean? We were lesser. Nicer, brighter, but still lesser.<br />

. . . And all the time we knew that Maureen Peal was not the Enemy and not<br />

worthy of such <strong>in</strong>tense hatred. The Th<strong>in</strong>g to fear was the Th<strong>in</strong>g that made<br />

her beautiful, and not us. (ibid., 74)<br />

Their community at large has accepted white (and light) sk<strong>in</strong> as beautiful—<br />

and thus has negated beauty <strong>in</strong> black (and darker) sk<strong>in</strong>. The girls, liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

this oppressive reality, must either accept the emotional violence forced on<br />

them, believ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their ugl<strong>in</strong>ess (which Pecola does) or fight back as aggressively<br />

as possible to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a positive self-image. They must rebel violently<br />

for their own self-preservation.

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 29<br />

And so they do. Focus<strong>in</strong>g on Maureen’s weaknesses—be<strong>in</strong>g born with six<br />

f<strong>in</strong>gers, hav<strong>in</strong>g a “dog tooth,” and a childish play on her name—Claudia and<br />

Freda attempt to restore power to themselves. Their verbal assault upends<br />

the power of white/light, refus<strong>in</strong>g the racialized and gendered expectations<br />

for young black girls and <strong>in</strong>stead creat<strong>in</strong>g a new vision of themselves as the<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ant figures. While they still suffer from the realization that their dark<br />

sk<strong>in</strong> is not as valued as Maureen’s light sk<strong>in</strong>, their verbal attack becomes<br />

their own act of rebellion, deny<strong>in</strong>g society’s oppression of them. Claudia<br />

and Freda’s self-esteem rema<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>tact, if d<strong>in</strong>ged, by society’s white obsessive<br />

compulsion.<br />

Likewise, the young girls <strong>in</strong> Sula also engage <strong>in</strong> childhood teas<strong>in</strong>g, but it<br />

quickly escalates <strong>in</strong>to self-mutilation, the accidental murder of a childhood<br />

friend and then conspiracy to avoid discovery and punishment. In an early<br />

scene, the title character and her best friend Nel attempt to outmaneuver four<br />

white teenage boys who enjoyed “harass<strong>in</strong>g black schoolchildren,” forc<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

girls to take “elaborate” paths home from school (Morrison 1982, 53). One<br />

day, Sula confronts the boys, pull<strong>in</strong>g out her grandmother’s “par<strong>in</strong>g knife. . .<br />

. Hold<strong>in</strong>g the knife <strong>in</strong> her right hand, she . . . presses her left foref<strong>in</strong>ger down<br />

hard on its edge. . . . She slashed off . . . the tip of her f<strong>in</strong>ger” (ibid., 54). Then,<br />

star<strong>in</strong>g at the boys, Sula says, “‘If I can do that to myself, what you suppose<br />

I’ll do to you?’” (ibid., 54–55). While some critics believe Sula’s action is<br />

an “<strong>in</strong>ternalized . . . lesson of racist oppression” (Bouson 2000, 63), it also<br />

can be read as an extreme example of redef<strong>in</strong>ed power. Sula’s will<strong>in</strong>gness<br />

to mutilate herself is a means to show strength, offer<strong>in</strong>g new realizations of<br />

what is capable with<strong>in</strong> violence. Instead of pitifully attack<strong>in</strong>g the boys, who<br />

are taller, older, and stronger, and not succeed<strong>in</strong>g, she chooses to harm that<br />

which she has the most control over: herself. 3 Attack<strong>in</strong>g herself shows Sula’s<br />

<strong>in</strong>ner courage and imag<strong>in</strong>ation to the boys, who quickly leave, realiz<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

their petty bully<strong>in</strong>g is no match for Sula’s actual self-violence and audacity.<br />

Thus, Sula transforms her status, reflect<strong>in</strong>g child and female powerlessness<br />

<strong>in</strong>to a terrible ferocity from which the bully<strong>in</strong>g white boys cannot depart<br />

fast enough. Regardless of her age, her sk<strong>in</strong> color, or her size, Sula becomes<br />

the dom<strong>in</strong>ant person <strong>in</strong> this altercation. She succeeds <strong>in</strong> rebell<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st the<br />

standards others have set for her (and others like her), forc<strong>in</strong>g everyone—the<br />

boys, Nel, and even readers—to view her differently afterward.<br />

Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, many of the girls <strong>in</strong> these novels learn their violent behaviors<br />

from with<strong>in</strong> their own families, frequently from other female characters,<br />

and often from their mothers or grandmothers, mak<strong>in</strong>g the violence <strong>in</strong>ter-

30 amanda putnam<br />

generational and matril<strong>in</strong>eal. Many of the women <strong>in</strong> Morrison’s novels are<br />

mothers who have been enslaved or otherwise victimized by <strong>in</strong>tense racism<br />

and oppression, which then embodies itself <strong>in</strong> violence toward their own,<br />

albeit sometimes as a mother<strong>in</strong>g tool.<br />

The home, then, becomes both a place of <strong>in</strong>spiration and violence, m<strong>in</strong>gl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the two <strong>in</strong> ways that are not easily separated. As bell hooks discusses <strong>in</strong><br />

“Homeplace,” the black domestic arena created by black women has been<br />

crucial to the reassurance of black children and their self-identities. She states,<br />

“Black women resisted [white oppression] by mak<strong>in</strong>g homes where all black<br />

people could strive to be subjects, not objects, where we could be affirmed <strong>in</strong><br />

our m<strong>in</strong>ds and hearts despite poverty, hardship, and deprivation, where we<br />

could restore to ourselves the dignity denied us on the outside <strong>in</strong> the public<br />

world” (hooks 1990, 42). Connect<strong>in</strong>g hooks’s po<strong>in</strong>t with Morrison’s stories<br />

means realiz<strong>in</strong>g the possibility that daughters may have learned violent patterns<br />

from lov<strong>in</strong>g mothers, as well as those who accepted white oppression.<br />

In other words, some black mothers may have <strong>in</strong>tentionally taught violent<br />

behaviors to their daughters to prepare for their daughters’ future survival <strong>in</strong><br />

a world that devalued them. Claudia Tate states, “[T]here’s a special k<strong>in</strong>d of .<br />

. . violence <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>gs by black women—not a bloody violence, but violence<br />

nonetheless. Love, <strong>in</strong> the Western notion, is full of possession, distortion, and<br />

corruption. It’s a slaughter without the blood” (as quoted <strong>in</strong> H<strong>in</strong>son 2001,<br />

147). When children learn violence from with<strong>in</strong> the home and from their<br />

caretakers, it becomes ord<strong>in</strong>ary and natural and, later, is <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to<br />

their own behaviors and thoughts. Thus, while readers def<strong>in</strong>itively notice<br />

the violence between generations, often the characters themselves do not<br />

articulate their feel<strong>in</strong>gs about the learned violent behaviors.<br />

Even so-called “good” mothers <strong>in</strong> several Morrison novels show slight<br />

violence at times toward their children, wreak<strong>in</strong>g havoc on their self-esteem<br />

and teach<strong>in</strong>g them to engage <strong>in</strong> violent behavior with others. 4 In one of<br />

the first scenes of The Bluest Eye, both Claudia and Freda get sick and the<br />

narration reflects the impatience of their typically car<strong>in</strong>g mother: “How . . .<br />

do you expect anybody to get anyth<strong>in</strong>g done if you all are sick?” (Morrison<br />

1994, 10). Claudia’s narration cont<strong>in</strong>ues: “My mother’s voice drones on. She<br />

is not talk<strong>in</strong>g to me. She is talk<strong>in</strong>g to the puke, but she is call<strong>in</strong>g it my name:<br />

Claudia” (ibid., 11). The sick girls feel unloved and miserable, even though<br />

their parents are normally nurtur<strong>in</strong>g and attentive. These simple acts of<br />

slight violence evoke pity for the girls, while show<strong>in</strong>g readers a world that is<br />

often uncomfortable or pa<strong>in</strong>ful: sometimes even lov<strong>in</strong>g mothers will <strong>in</strong>flict

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 31<br />

emotional abuse on their children, which, <strong>in</strong> turn, teaches them to repeat<br />

the abuse on each other.<br />

Similarly, <strong>in</strong> Sula, Helene Wright’s desire to remove herself and her daughter<br />

completely from the ta<strong>in</strong>t of the whorehouse Helene had been born <strong>in</strong><br />

manifests itself <strong>in</strong> quash<strong>in</strong>g Nel’s curiosity: “Any enthusiasms that little Nel<br />

showed were calmed by the mother until [Helene] drove her daughter’s<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>ation underground” (Morrison 1982, 18). Helene’s worry that Nel will<br />

portray any semblance of the qualities of Helene’s prostitute mother <strong>in</strong>dicates<br />

her will<strong>in</strong>gness to sacrifice strong qualities of creativity or <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

for meek obedience. In do<strong>in</strong>g so, Nel’s “parents had succeeded <strong>in</strong> rubb<strong>in</strong>g<br />

down to a dull glow any sparkle or splutter she had” (ibid., 83). The girl’s<br />

obedience is steadfast, but the parental violence to her maturation process<br />

forces Nel to develop <strong>in</strong>to a woman who does not understand the options<br />

available to her as an adult. Unlike Sula who becomes a dom<strong>in</strong>ant force <strong>in</strong><br />

her own life, Nel meekly follows along, hav<strong>in</strong>g suffered the passive violence<br />

of her mother’s repression.<br />

In several Morrison novels, maternal emotional abandonment changes<br />

children (usually daughters) <strong>in</strong> unfavorable ways, caus<strong>in</strong>g them to <strong>in</strong>flict<br />

violence on others. In The Bluest Eye, Gerald<strong>in</strong>e met all the “physical needs”<br />

of her son Junior, but it is pa<strong>in</strong>fully clear to him (and to readers) that she<br />

prefers the cat (Morrison 1994, 85–86). The subtle but emotionally effective<br />

violence of withhold<strong>in</strong>g motherly affection contributes to Junior’s eventual<br />

desire to “bully girls” (ibid., 87), and he becomes a tyrant to any child younger<br />

or smaller than him.<br />

In Morrison’s newest novel, A Mercy, another “good” mother chooses<br />

to send away her young enslaved daughter, <strong>in</strong> the hope of prevent<strong>in</strong>g her<br />

daughter from be<strong>in</strong>g sexually abused. 5 However, without acknowledgment<br />

of the reason<strong>in</strong>g for this choice, the daughter <strong>in</strong>ternalizes what she perceives<br />

as her mother’s emotional and physical abandonment, eventually erupt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> more violence aga<strong>in</strong>st a future rival. In the first chapter of A Mercy, Florens,<br />

who is “maybe seven or eight” (Morrison 2008, 5) misunderstands her<br />

mother’s reason<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> send<strong>in</strong>g her away with a new owner as payment of a<br />

debt, <strong>in</strong>stead of go<strong>in</strong>g with her to the new place. Florens remembers, with<br />

childlike sadness, “forever and ever. Me watch<strong>in</strong>g, my mother listen<strong>in</strong>g, her<br />

baby boy on her hip. Senhor is not pay<strong>in</strong>g the whole amount he owes to Sir.<br />

Sir say<strong>in</strong>g he will take <strong>in</strong>stead the woman and the girl, not the baby boy and<br />

the debt is gone. A m<strong>in</strong>ha mãe begs no. Her baby boy is still at her breast.<br />

Take the girl, she says, my daughter, she says. Me. Me” (ibid., 7). The betrayal<br />

Florens feels is evident <strong>in</strong> her version—her pa<strong>in</strong> as she repeats “Me. Me . . .

32 amanda putnam<br />

forever and ever” illustrates to readers that she cannot believe her mother<br />

has just given her away to be separated forever from her. Of course, neither<br />

mother nor daughter is free—so the mother actually has no options. She<br />

simply begs to provide for both children. Unfortunately, the young Florens<br />

understands the situation as her mother choos<strong>in</strong>g a baby brother over the<br />

older daughter. Florens shares her grow<strong>in</strong>g perception of the situation by<br />

add<strong>in</strong>g that “mothers nurs<strong>in</strong>g greedy babies scare me. I know how their eyes<br />

go when they choose . . . hold<strong>in</strong>g the little boy’s hand” (ibid., 8). Instead of<br />

realiz<strong>in</strong>g the great sacrifice her mother has just made for her daughter, Florens<br />

only understands her own abandonment—and this shapes her entire future.<br />

Thus, even though Florens’s mother actually had pure <strong>in</strong>tentions—valu<strong>in</strong>g<br />

her daughter more than herself to save the child from potential sexual<br />

abuse—the outcome of not choos<strong>in</strong>g to stay with Florens negatively affects<br />

the girl throughout her life, wreak<strong>in</strong>g havoc on the child’s self-esteem and<br />

her ability to nurture any other relationship successfully. Eventually, readers<br />

discover that Florens’s mother chooses to send her daughter because she<br />

believes “Sir” has “no animal <strong>in</strong> his heart” (Morrison 2008, 163) versus the<br />

men <strong>in</strong> the house <strong>in</strong> which they are currently resid<strong>in</strong>g, who have raped the<br />

mother multiple times and are already notic<strong>in</strong>g Florens’s chang<strong>in</strong>g body<br />

(ibid., 162). The mother sees her chance for Florens: “Because I saw the tall<br />

man see you as a human child . . . I knelt before him. Hop<strong>in</strong>g for a miracle.<br />

He said yes” (ibid., 166). Begg<strong>in</strong>g to save her <strong>in</strong>fant son (who will likely die<br />

without her care) as well as provide a life-alter<strong>in</strong>g opportunity for her daughter,<br />

this mother gives away her own chance of liv<strong>in</strong>g a better life so that both<br />

her children will survive. In this case, Florens’s mother shows a similarity to<br />

other enslaved mothers. As hooks expla<strong>in</strong>s, “In the midst of a brutal racist<br />

system, which did not value black life, [the slave mother] valued the life of<br />

her child enough to resist that system” (1990, 44). While hooks is actually<br />

revis<strong>in</strong>g Frederick Douglass’s negative description of his own mother, who<br />

walked twelve miles whenever possible to hold him at night, the description<br />

is a valid one <strong>in</strong> this case, too. Florens’s mother goes to great strides to give<br />

her children the best opportunity available.<br />

Unfortunately, the lack of explanation for her mother’s actions and<br />

choices creates a distrust <strong>in</strong> Florens, which she carries with her throughout<br />

the novel, eventually end<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a violent reaction toward a child she views as<br />

a competitor. Florens’s love affair with a freedman and her unwill<strong>in</strong>gness to<br />

share him with an orphaned boy reflects the violence she has felt her whole<br />

life from her mother. When she <strong>in</strong>itially meets the boy, Florens immediately<br />

recognizes her predicament: “This happens twice before. The first time it is

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 33<br />

me peer<strong>in</strong>g around my mother’s dress hop<strong>in</strong>g for a hand that is only for her<br />

little boy. . . . Both times are full of danger and I am expel” (Morrison 2008,<br />

135–37). Worried that she aga<strong>in</strong> will be replaced or excluded, she cannot see<br />

that her lover could love more than one person: “I worry as the boy steps<br />

closer to you . . . As if he is your future. Not me” (ibid., 136). Assum<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

boy also wants her absence, Florens narrates her understand<strong>in</strong>g of him: “He<br />

is silent but the hate <strong>in</strong> his eyes is loud. He wants my leav<strong>in</strong>g. This cannot<br />

happen. I feel the clutch <strong>in</strong>side. This expel can never happen aga<strong>in</strong>” (ibid.,<br />

137). Eventually, Florens attacks the child and shares, “And yes I do hear the<br />

shoulder crack but the sound is small. . . . He screams screams then fa<strong>in</strong>ts”<br />

(ibid., 139–40). The lover reappears at this moment, hav<strong>in</strong>g seen the attack,<br />

and is outraged and angered, ironically reject<strong>in</strong>g Florens, not because he<br />

favors the boy but because he has seen the violence <strong>in</strong>side her, bred and fostered<br />

with<strong>in</strong> slavery and that system’s forcible abandonment by her mother.<br />

While Florens is not able to use violence to get what she wants (her lover), it<br />

is still a rebellious action taken aga<strong>in</strong>st her circumstances. Florens’s violent<br />

attack on the child—and then moments later on her lover—only makes<br />

sense when readers understand her m<strong>in</strong>dset as the daughter sent away by<br />

her mother. Sent away by both her mother and lover, Florens cannot make<br />

sense of the past to create a new life, even <strong>in</strong> freedom. Nonetheless, <strong>in</strong> this<br />

desperate act of violence, Florens rebels aga<strong>in</strong>st the limitations of societal<br />

behavior, tak<strong>in</strong>g action and refus<strong>in</strong>g to accept abandonment yet aga<strong>in</strong>.<br />

The tragedy, of course, is that Florens’s mother was try<strong>in</strong>g to save her<br />

daughter (and likewise her lover was simply be<strong>in</strong>g k<strong>in</strong>d to an abandoned boy),<br />

but, without that crucial piece of <strong>in</strong>formation from her enslaved mother,<br />

Florens does not learn to navigate relationships or learn to trust—and so the<br />

<strong>in</strong>nocent and self-martyr<strong>in</strong>g act of rescue from the mother becomes also an<br />

act of violence, sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> motion her daughter’s future brutality and ultimate<br />

self-destruction.<br />

Similarly, <strong>in</strong> Sula, readers see aga<strong>in</strong> how emotional trauma via mother<br />

violence can affect the development of social empathy and compassion,<br />

thereby creat<strong>in</strong>g subsequent generations of violent females. The pa<strong>in</strong> Sula<br />

feels upon discover<strong>in</strong>g her mother’s op<strong>in</strong>ion of her damages the young girl’s<br />

self-concept, prepar<strong>in</strong>g Sula to become a violent and distant teenager and<br />

adult. Sula’s first realization of her mother’s apathy to her segues <strong>in</strong>to a scene<br />

of accidental violence toward another child and later <strong>in</strong>to a coldness toward<br />

death <strong>in</strong> general. After Sula hears her mother, Hannah, expla<strong>in</strong> that, while she<br />

had maternal feel<strong>in</strong>gs for Sula, she did not like her, Sula feels “bewilderment<br />

. . . [and] a st<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> her eye” (Morrison 1982, 57). Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, Hannah, asks

34 amanda putnam<br />

her own mother, Eva, “‘did you ever love us?’” (ibid., 67). Eva, angered by<br />

the question, <strong>in</strong>dicates she did not. Thus, it is not surpris<strong>in</strong>g that Hannah<br />

repeats this type of phras<strong>in</strong>g (and abuse) to her own daughter, not will<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

recogniz<strong>in</strong>g the damage <strong>in</strong>flicted on herself <strong>in</strong> the same situation. But Sula’s<br />

maternal abandonment is real and affects her self-image. Suddenly, Sula is<br />

vulnerable, s<strong>in</strong>ce (like Pecola), if a young black girl cannot expect her own<br />

mother to enjoy her unconditionally, it is unlikely that the rest of the world<br />

will do so.<br />

Comprehend<strong>in</strong>g her vulnerability for the first time, Sula recovers via<br />

violence toward another child. The scene quickly changes from Sula’s household<br />

6 to Sula and Nel play<strong>in</strong>g near a river and trees with a little boy named<br />

Chicken Little. After climb<strong>in</strong>g up and down a tree with the little boy, Sula<br />

playfully “picked him up by his hands and swung him outward then around<br />

and around . . . [and] when he slipped from her hands and sailed away out<br />

over the water they could still hear his bubbly laughter” (Morrison 1982,<br />

60–61). However, the boy does not emerge from the water; and <strong>in</strong>stead of<br />

try<strong>in</strong>g to save him, both girls wait to see what happens. In fact, the first th<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Nel says is “‘Somebody saw,’” (61) suggest<strong>in</strong>g that the girls are far more<br />

concerned about someone see<strong>in</strong>g them watch a child drown than the actual<br />

passivity of their actions. The girls do not tell anyone what happened, and<br />

Chicken Little’s water-engorged body is eventually found and buried a few<br />

days later.<br />

But the emotional violence of discover<strong>in</strong>g Sula’s mother’s passive hostility<br />

for her helps create a detachment <strong>in</strong> Sula, allow<strong>in</strong>g her to watch death<br />

and other tragedies from an easy distance. Sula later watches her mother<br />

burn to death <strong>in</strong> their backyard, and grandmother Eva believes the girl did<br />

so out of twisted curiosity. Hav<strong>in</strong>g learned from her mother the possibility<br />

of lov<strong>in</strong>g, but rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g remote, and hav<strong>in</strong>g learned from her grandmother<br />

that murder may be a part of family life (as Eva murders her own son), Sula<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s aloof from her mother’s fiery death, just as she was when she accidently<br />

killed Chicken Little.<br />

In fact, later <strong>in</strong> the novel, it is clear that Sula connects her emotional<br />

trauma from her mother with her personal detachment. The <strong>in</strong>tense pa<strong>in</strong> of<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g her mother does not like her bl<strong>in</strong>ds Sula to feel<strong>in</strong>g a normal amount<br />

of social compassion, which then manifests itself through violence toward<br />

others. Sula recounts her new understand<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

As will<strong>in</strong>g to feel pa<strong>in</strong> as to give pa<strong>in</strong>, to flee pleasure as to give pleasure,<br />

hers was an experimental life—ever s<strong>in</strong>ce her mother’s remarks sent her

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 35<br />

fly<strong>in</strong>g up those stairs, ever s<strong>in</strong>ce her one major feel<strong>in</strong>g of responsibility had<br />

been exorcised on the bank of a river with a closed place <strong>in</strong> the middle. The<br />

first experience taught her there was no other that you could count on; the<br />

second that there was not self to count on either. (Morrison 1982, 118–19)<br />

Thus, Sula’s distant and even cruel teenage and adult behaviors toward others<br />

are taught to her by other women <strong>in</strong> her household. Escap<strong>in</strong>g the pa<strong>in</strong> of<br />

emotional maternal abandonment, Sula mimics that distance to others for<br />

the rest of the novel. In fact, when Sula returns to the town as an adult, she<br />

quickly puts her grandmother Eva <strong>in</strong>to a nurs<strong>in</strong>g home, <strong>in</strong>stead of car<strong>in</strong>g for<br />

her herself, and is massively condemned for it by the townspeople (ibid., 112).<br />

And yet, her decision makes sense to her because she recognizes no personal<br />

connection to her grandmother (or to her dead mother)—and they are the<br />

ones who taught her how to feel that way. She rebels aga<strong>in</strong>st standard expectations<br />

for daughters (and women at large), ignor<strong>in</strong>g the dictates of society<br />

and behav<strong>in</strong>g with passive violence to those who taught her those emotions.<br />

Regardless of the community’s feel<strong>in</strong>gs for her, though, Sula is clearly<br />

recognized as an empowered, tough woman. She has sexual relations with<br />

anyone she wants, regardless of race or marital status; is <strong>in</strong>solent to her<br />

grandmother and adult men; and puts her own needs before those of others.<br />

In a novel where Nel’s mother turns to “custard” try<strong>in</strong>g to appease a racist<br />

white man (Morrison 1982, 22), Sula is a character foil, reflect<strong>in</strong>g strength<br />

and boldness, even though that same power occasionally hurts—and even<br />

kills—others near her.<br />

Other mothers <strong>in</strong> Morrison’s novels move beyond emotional child<br />

abuse, add<strong>in</strong>g stark physical violence, creat<strong>in</strong>g additional havoc <strong>in</strong> the children’s<br />

levels of self-esteem. At one po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> The Bluest Eye, readers witness<br />

yet another scene show<strong>in</strong>g terrible disparity <strong>in</strong> the treatment of white and<br />

black girls, but this time the scene also highlights the potential brutality of<br />

mother-daughter relations. When Pecola accidentally knocks over a pie <strong>in</strong> the<br />

house <strong>in</strong> which her mother works, her legs are burnt by the blueberry juice.<br />

Instead of comfort<strong>in</strong>g her daughter, Paul<strong>in</strong>e Breedlove hits her “with the<br />

back of her hand knock[<strong>in</strong>g] her to the floor” (Morrison 1994, 109). While<br />

it is understandable that Paul<strong>in</strong>e is angry—the pie is for the white family<br />

she works for, which could cost her both time and money; additionally, the<br />

accident has “splatter[ed] blackish blueberries everywhere” (ibid., 108) <strong>in</strong> the<br />

prist<strong>in</strong>e kitchen, essentially creat<strong>in</strong>g even more work for Paul<strong>in</strong>e. Regardless<br />

of the validity of the issues, Paul<strong>in</strong>e’s anger at Pecola, her own daughter, is<br />

out of proportion, especially when readers see how she comforts the white

36 amanda putnam<br />

daughter of the family who employs her, “hush<strong>in</strong>g and sooth<strong>in</strong>g the tears<br />

of the little p<strong>in</strong>k-and-yellow girl” (ibid., 109). Clearly, this mother is out of<br />

sync with her maternal feel<strong>in</strong>gs, lushly nurtur<strong>in</strong>g the child of her employers,<br />

while physically abus<strong>in</strong>g and neglect<strong>in</strong>g her own daughter; but it reflects the<br />

race-based oppression under which they all live. Likewise, the violence—both<br />

physical and emotional—that she <strong>in</strong>flicts on Pecola is obscene, especially <strong>in</strong><br />

comparison to her mother<strong>in</strong>g behavior toward another child. Pecola absorbs<br />

this ill-treatment, eventually accept<strong>in</strong>g abuse from all corners of her life as<br />

her due, direct<strong>in</strong>g her learned violence on herself alone.<br />

Likewise, Paul<strong>in</strong>e Breedlove believes it is her Christian duty to punish<br />

her alcoholic husband and thus co-creates constant domestic disturbances<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the family, <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g fights with her husband, Cholly, which, <strong>in</strong> turn,<br />

encourages more violence from her children. In one such scene, after a verbal<br />

fight between husband and wife escalates <strong>in</strong>to a physical one, the son actively<br />

jo<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> hitt<strong>in</strong>g his drunk father, eventually yell<strong>in</strong>g, “‘Kill him! Kill him!’”<br />

(Morrison 1994, 44). While Mrs. Breedlove barely reacts to her son’s emotional<br />

and physical outburst, his <strong>in</strong>tensity is deeply felt by the reader who sees<br />

<strong>in</strong> him another generation of violence wait<strong>in</strong>g to blossom. However, even if<br />

readers do not care for Paul<strong>in</strong>e Breedlove, it is also clear that she redirects<br />

her own powerlessness <strong>in</strong> these situations. Mrs. Breedlove is a force to be<br />

reckoned with—if only to her daughter, son, and husband. Regardless of<br />

anyth<strong>in</strong>g else, like Florens <strong>in</strong> A Mercy, Breedlove becomes powerful through<br />

violence, redef<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g herself via it.<br />

In most of these examples, Morrison positions the home and immediate<br />

family relationships as places of potentially terrible pa<strong>in</strong>. As Carole Boyce<br />

Davies expla<strong>in</strong>s, “The family is sometimes situated as a site of oppression<br />

for women. The mystified notions of home and family are removed from<br />

their romantic, idealized moor<strong>in</strong>gs, to speak of pa<strong>in</strong>, movement, difficulty,<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g and love <strong>in</strong> complex ways” (1994, 21). These families become real<br />

for readers—they break hearts, they hurt each other, and they do not always<br />

apologize. And though some of the mothers <strong>in</strong> Morrison’s novels mentioned<br />

here genu<strong>in</strong>ely love their children, they also cannot remove the violence that<br />

is as a learned part of their lives with<strong>in</strong> an oppressive culture as is their desire<br />

to nurture.<br />

In the most f<strong>in</strong>al violence possible, some mothers <strong>in</strong> Morrison’s novels<br />

choose to end the lives of their children—<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fancy and childhood (Beloved)<br />

or even <strong>in</strong> adulthood (Sula), attempt<strong>in</strong>g to offer an escape from someth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

considered worse than death <strong>in</strong> their maternal m<strong>in</strong>ds. By choos<strong>in</strong>g death

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 37<br />

for their children, these mothers are def<strong>in</strong>itively demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g the ways <strong>in</strong><br />

which fatal violence becomes an act of rebellion and a form of resistance.<br />

In Sula, Eva Peace transforms her position of weakness <strong>in</strong>to power, by<br />

determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g what k<strong>in</strong>d of life is worth her son’s liv<strong>in</strong>g and then choos<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to kill him. When her son Plum comes home from World War I addicted to<br />

hero<strong>in</strong>, Eva waits to see if he will change his ways. Eventually, though, Eva<br />

“threw [a lit newspaper] onto the bed where the kerosene-soaked Plum lay”<br />

(Morrison 1982, 47), burn<strong>in</strong>g him to death to prevent his cont<strong>in</strong>ued life of<br />

drug addiction. Later, Eva expla<strong>in</strong>s it:<br />

he wanted to crawl back <strong>in</strong>to my womb and well . . . There wasn’t space .<br />

. . Be<strong>in</strong>g helpless and th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g baby thoughts and dream<strong>in</strong>g baby dreams<br />

and mess<strong>in</strong>g up his pants aga<strong>in</strong> and smil<strong>in</strong>g all the time. I had room <strong>in</strong> my<br />

heart, but not <strong>in</strong> my womb. . . . I done everyth<strong>in</strong>g I could to make him leave<br />

me and go on and live and be a man but he wouldn’t and I had to keep him<br />

out so I just thought of a way he could die like a man not all scrunched up<br />

<strong>in</strong>side my womb, but like a man. (ibid., 71–72)<br />

Eva’s decision has more to do with her own state of m<strong>in</strong>d than Plum’s (who<br />

is “smil<strong>in</strong>g all the time”). As his mother, she makes it her decision whether<br />

he should live a life of addiction. Powerless to change his behaviors and/or<br />

make him “live and be a man,” Eva redirects her status of helplessness <strong>in</strong>to<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ant female strength and murders Plum.<br />

Beloved’s Sethe, the mother of four children, is well known for her attempt<br />

to kill her children, once she realizes they are about to be taken back <strong>in</strong>to<br />

slavery. After be<strong>in</strong>g free for twenty-eight days, Sethe takes control of the situation<br />

the only way she knows how: by destroy<strong>in</strong>g the “property” for which<br />

the bounty hunter and slaveowner have come, because Sethe “wasn’t go<strong>in</strong>g<br />

back there . . . Any life but that one” was preferable (Morrison 1988, 42).<br />

As Boyce Davies suggests, “Beloved . . . simultaneously critiques exclusive<br />

mother-love as it asserts the necessity for Black women to claim someth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

as theirs” (1994, 136). Similarly, Christopher Peterson’s analysis <strong>in</strong>dicates<br />

that Sethe must “kill her own daughter . . . to claim that daughter as her own<br />

over and above the master’s claim” (2006, 554). Sethe’s decision can only be<br />

understood when readers recognize the entirety of the choices available to<br />

her and realize that, via violence, Sethe redirects her racialized powerlessness<br />

<strong>in</strong>to maternal possession and dom<strong>in</strong>ance.<br />

In Beloved, readers see how maternal love can be so overwhelm<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

a mother might decide to kill her offspr<strong>in</strong>g rather than return them to a life<br />

not worth liv<strong>in</strong>g. Once Sethe escapes from slavery, f<strong>in</strong>ally reach<strong>in</strong>g her three

38 amanda putnam<br />

older children with her newborn baby tied to her, her mother love is plentiful:<br />

“Sethe lay <strong>in</strong> bed under, around, over, among, but especially with them<br />

all” (Morrison 1988, 93). Unlike some other of Morrison’s mothers who<br />

deny their mother love (like Baby Suggs), Sethe revels <strong>in</strong> it, both <strong>in</strong> times of<br />

happ<strong>in</strong>ess and <strong>in</strong> despair. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Christopher Peterson, Orlando Patterson<br />

argues that “slavery destroys slave k<strong>in</strong>ship structures” (Peterson 2006,<br />

549). Sethe actually shows abundant connections to her children, risk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

everyth<strong>in</strong>g for them to escape and celebrat<strong>in</strong>g their life together afterward.<br />

But believ<strong>in</strong>g capture (and subsequent torture) imm<strong>in</strong>ent, Sethe rebels<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st societal mores that suggest mother<strong>in</strong>g is nonviolent and takes desperate<br />

action. The four white men open the shed door, see<strong>in</strong>g that “two boys<br />

bled <strong>in</strong> the sawdust and . . . a nigger woman hold<strong>in</strong>g a blood-soaked child<br />

to her chest” is sw<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>fant “by the heels . . . toward the wall planks”<br />

(Morrison 1988, 149). Her actions are unth<strong>in</strong>kable and brutal, yet readers<br />

cannot doubt the truth of both her maternal love and her power. “Because<br />

the normative vision of maternity tends to elevate the mother/child relation<br />

to an idealized field of ethical action, <strong>in</strong>fanticide is most often read either<br />

as an un<strong>in</strong>telligible aberration from normative k<strong>in</strong>ship, or as an act of pure<br />

love, <strong>in</strong> which case it is thought to be completely <strong>in</strong>telligible” (Peterson 2006,<br />

551). While Sethe’s actions are ghastly, they are also compell<strong>in</strong>gly dom<strong>in</strong>ant—she<br />

chooses what will happen to her and to her children. As Peterson<br />

argues, “What Sethe claims signifies not only her daughter, but also what<br />

she claims for her act of <strong>in</strong>fanticide: namely, that it is an act of pure love”<br />

(2006, 555). Sethe reprojects the violence that has oppressed her for years<br />

and takes control of what little she can. Sethe loves her children enough to<br />

choose death for them <strong>in</strong>stead of a tortuous slave life.<br />

Even months and years later, after be<strong>in</strong>g faced with prison and decades<br />

of scorn with<strong>in</strong> her community, Sethe defends her maternal violence. She<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>s to Paul D., “I did it. I got us all out. . . . I couldn’t let all that go back<br />

to where it was, and I couldn’t let her nor any of em live under schoolteacher”<br />

(Morrison 1988, 162–63). Even more tell<strong>in</strong>g are Sethe’s thoughts when she<br />

recognizes the slaveowner’s hat <strong>in</strong> the front lawn that fateful day:<br />

No. No. Nono. Nonono. Simple. She just flew. Collected every bit of life she<br />

had made, all the parts of her that were precious and f<strong>in</strong>e and beautiful, and<br />

carried, pushed, dragged them through the veil, out, away, over there where<br />

no one could hurt them. Over there. Outside this place, where they would<br />

be safe. (ibid., 163)<br />

Unwill<strong>in</strong>g to sacrifice her children’s right to freedom, familial connections,

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 39<br />

and even daily decision mak<strong>in</strong>g (someth<strong>in</strong>g she herself rarely enjoyed until<br />

her escape), she chooses violent death <strong>in</strong>side family unity. Expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g about<br />

cutt<strong>in</strong>g her own daughter’s throat, Sethe says, “if I hadn’t killed her she<br />

would have died and that is someth<strong>in</strong>g I could not bear to happen to her”<br />

(ibid., 200). For Sethe, slavery (especially be<strong>in</strong>g owned by the awful Schoolteacher)<br />

is death—a death of the spirit and m<strong>in</strong>d as well as body—and it is<br />

worse than any physical dy<strong>in</strong>g because it occurs without any connection to<br />

significant others. Sethe’s lack of knowledge about her mother’s life or death,<br />

her husband’s disappearance, and their friends’ outcomes after escape all<br />

direct her to realize that mak<strong>in</strong>g an awful choice can be better than hav<strong>in</strong>g<br />

no choice at all. As Boyce Davies expla<strong>in</strong>s, “Sethe’s violent action becomes<br />

an attempt to hold on to the maternal right and function” (1994, 139). After<br />

freedom had been achieved, Sethe accepted the burden of power that came<br />

with keep<strong>in</strong>g that freedom at all costs. She acts rebelliously, will<strong>in</strong>g to die and<br />

kill <strong>in</strong> order to claim her children as her own, above any claim of property<br />

by Schoolteacher.<br />

Though Sethe is the most <strong>in</strong>famous for her brutal maternal decision, she<br />

is not the only mother <strong>in</strong> Beloved who resorts to violence—and readers can<br />

learn how and why Sethe comes to her own ferocious mother<strong>in</strong>g decision by<br />

notic<strong>in</strong>g more about her relationship (and/or the lack of that relationship)<br />

with her own mother. Known only as “Ma’am,” Sethe’s mother works <strong>in</strong><br />

the rice fields and is a stranger to Sethe, but she is the only child of Ma’am’s<br />

that is encouraged to live and thus <strong>in</strong>doctr<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong>to Sethe the concept of<br />

mothers choos<strong>in</strong>g life or death for their children. Another slave woman tells<br />

Sethe about Sethe’s conception and birth after Ma’am’s death: “‘She threw<br />

them all away but you. The one from the crew she threw away on the island.<br />

The others from more whites she also threw away. Without names, she threw<br />

them. You she gave the name of the black man. She put her arms around him.<br />

The others she did not put her arms around’” (Morrison 1988, 62). The story,<br />

which implicitly expla<strong>in</strong>s the horrors of multiple rapes upon Ma’am, also<br />

recognizes the power of maternal choice. Ma’am could not escape rape and<br />

subsequent pregnancy, but she rebelled, by refus<strong>in</strong>g motherhood until she<br />

was impregnated by someone whom she had accepted. Ma’am’s actions and<br />

decisions are not discussed more fully <strong>in</strong> the novel, but they surely would have<br />

taught Sethe the importance of power, choice, rebellion, and motherhood.<br />

Although technically “unimpressed” with the story as a child, the concept<br />

(and power) of choos<strong>in</strong>g motherhood (and thus also the special burdens of<br />

decid<strong>in</strong>g life or death for your offspr<strong>in</strong>g) is established for Sethe from early<br />

on <strong>in</strong> her life.

40 amanda putnam<br />

Additionally, <strong>in</strong> one of the few positive memories Sethe has with her<br />

mother, violence marks the moment that focuses on possession and recognition,<br />

encrypt<strong>in</strong>g Sethe with the understand<strong>in</strong>g that maternal violence is<br />

easily also an act of love. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>fancy, it is another woman’s job to nurse<br />

Sethe and later, an eight-year-old child watches her while her mother works<br />

<strong>in</strong> the fields. However, Ma’am takes Sethe aside one day to show her a brand<br />

below her ribs, burnt there by slaveowners. Ma’am shows this mark so that “if<br />

someth<strong>in</strong>g happens to [her] and [Sethe] can’t tell [her] by [her] face, [Sethe]<br />

can know [Ma’am] by this mark” (Morrison, 1988, 61). Sethe, encouraged<br />

by what is an unusual token of familiar possession between them, asks her<br />

mother to “‘Mark the mark on me too’” (ibid.) so that they would be similar<br />

to one another. But Ma’am slaps Sethe for the remark, not want<strong>in</strong>g her own<br />

daughter to be burnt but not expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g why.<br />

Readers understand this scene through multiple lenses. First, the act of<br />

recognition between mother and daughter is key—the mother is ensur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that, despite the probable violence that will end her own life (which is accurate—Ma’am<br />

is lynched), she wants her daughter to be able to recognize her<br />

body and know why she is then absent (i.e., unlike the mysteries of absences<br />

related to so many others, like Sethe’s husband). But Sethe, unmothered by<br />

slavery, is unable to understand—<strong>in</strong>stead, she wants to bond with her mother<br />

by display<strong>in</strong>g the same mark as she has—show<strong>in</strong>g that she and her mother<br />

share the same symbol. Second, and perhaps even more importantly, Sethe<br />

learns that maternal violence—hitt<strong>in</strong>g the child to express your po<strong>in</strong>t—can<br />

be an expression of possession and even love. Sethe learns from this poignant<br />

memory that violence can mark the relationship of mother to child, so readers<br />

should not be surprised when she turns to violence later to protect and<br />

show her possession of her own children.<br />

Sethe’s understand<strong>in</strong>g of her mother also allows her to expla<strong>in</strong> Ma’am’s<br />

death <strong>in</strong> terms of their connection to each other. When Ma’am is lynched,<br />

Sethe wonders what her mother did to deserve dy<strong>in</strong>g: “Runn<strong>in</strong>g, you th<strong>in</strong>k?<br />

No. Not that. Because she was my ma’am and nobody’s ma’am would run<br />

off and leave her daughter” (ibid., 203). Sethe’s immediate refusal of this<br />

particular action as the reason for the lynch<strong>in</strong>g—runn<strong>in</strong>g off without tak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Sethe with her—reflects her own understand<strong>in</strong>g of familial connections.<br />

Sethe would never physically abandon her children to save herself—her ability<br />

to mother them is demanded via proximity and decision mak<strong>in</strong>g—even<br />

to the po<strong>in</strong>t of choos<strong>in</strong>g the time and means of their deaths, if necessary.<br />

While other mothers <strong>in</strong> Beloved condemn Sethe for her violent mother<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

many of them also engage <strong>in</strong> maternal violence <strong>in</strong> various ways, as well as

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 41<br />

treat Sethe’s family with violence for decades. While Sethe’s mother-<strong>in</strong>-law<br />

Baby Suggs denounces the choice Sethe makes <strong>in</strong> the shed with her children,<br />

she also recognizes her own losses via slavery:<br />

Seven times she had done that: held a little foot; exam<strong>in</strong>ed the fat f<strong>in</strong>gertips<br />

with her own—f<strong>in</strong>gers she never saw become the male or female hands a<br />

mother would recognize anywhere. She didn’t know to this day what their<br />

permanent teeth looked like; or how they held their heads when they walked.<br />

Did Patty lose her lisp? What color did Famous’ sk<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ally take? Was that<br />

a cleft <strong>in</strong> Johnny’s ch<strong>in</strong> or just a dimple that would disappear soon’s his<br />

jawbone changed? Four girls, and the last time she saw them there was no<br />

hair under their arms. Does Ardelia still love the burned bottom of bread?<br />

All seven were gone or dead. What would be the po<strong>in</strong>t of look<strong>in</strong>g too hard<br />

at that youngest one? (Morrison 1988, 139)<br />

So while Baby Suggs does not murder her children, she does determ<strong>in</strong>e to<br />

deal with the pa<strong>in</strong> of los<strong>in</strong>g her children by not lov<strong>in</strong>g them (ibid., 23)—<br />

which does not quite work. For example, when she hears that two children<br />

(Nancy and Famous) died on a ship wait<strong>in</strong>g to leave harbor, she “covered her<br />

ears with her fists to keep from hear<strong>in</strong>g” (ibid., 144). Peterson expla<strong>in</strong>s that<br />

Suggs’s methodology is due to “the threat of white violence [which] has conditioned<br />

former slaves not to attach themselves too strongly to the th<strong>in</strong>gs they<br />

love” (2006, 153). Aga<strong>in</strong>, while Baby Suggs believes she is on a higher moral<br />

ground than Sethe, the reality is that Baby Suggs forced herself to abandon<br />

her children almost at birth, know<strong>in</strong>g that they will eventually be taken away<br />

with<strong>in</strong> slavery. In contrast, Sethe never abandons her children—she rema<strong>in</strong>s<br />

constant for them, even though her method of mother<strong>in</strong>g becomes brutal.<br />

Similarly, even Ella, a woman who also does not condone the choices<br />

Sethe has made, has her own secret mother violence: “She had delivered,<br />

but would not nurse, a hairy white th<strong>in</strong>g, fathered by ‘the lowest yet.’ It lived<br />

five days never mak<strong>in</strong>g a sound.” (Morrison 1988, 258–59). These choices of<br />

maternal neglect show that mother violence takes many forms, and, while<br />

Sethe is condemned for her public choice of brutality, there are several others<br />

who similarly make hard decisions about their own offspr<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

These female characters, all flawed but also all attempt<strong>in</strong>g to manage<br />

situations far beyond their control, choose violence. In do<strong>in</strong>g so, they transform<br />

from powerless subord<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong>to dom<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g forces, even though that<br />

transformation often has multidimensional repercussions for them and<br />

those with whom they have chosen to be violent. As young girls, mothers,<br />

and grandmothers, they act <strong>in</strong> unsanctioned ways, forc<strong>in</strong>g a redef<strong>in</strong>ition of

42 amanda putnam<br />

what black femaleness and black motherhood can and should be, especially<br />

under oppressive conditions. Through multiple generations of violent patterns<br />

(reflect<strong>in</strong>g the viciousness of racist society around them), children<br />

learn violence and become violent themselves, and violent mothers may<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d themselves unmothered by murder<strong>in</strong>g their own children, depict<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

repetitive ghastl<strong>in</strong>ess with<strong>in</strong> Morrison families.<br />

And yet these female characters rema<strong>in</strong> powerful, dom<strong>in</strong>ant, and <strong>in</strong>trigu<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

They face horrendously oppressive circumstances and create new end<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

to them, which their oppressors can hardly believe. They redirect their<br />

powerless positions, transform<strong>in</strong>g themselves <strong>in</strong>to haunt<strong>in</strong>gly forceful girls<br />

and women. They choose their own dest<strong>in</strong>ies, even if those futures are often<br />

lonely or tragic. Thus, these violent females provide a new understand<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

violence and its relationship to personal power and community.<br />

Endnotes<br />

1. Orig<strong>in</strong>al emphasis.<br />

2. While Carol Iannone (1987) po<strong>in</strong>ted out <strong>in</strong> her criticisms of Morrison that this type<br />

of black-on-black cruelty also repeatedly shows black life as strangely traumatic and/or<br />

disturb<strong>in</strong>g, that commentary underplays the reality of absorbed white-societal obsessiveness—and<br />

the need for these young girls to rebel aga<strong>in</strong>st those constra<strong>in</strong>ts.<br />

3. While some critics, such as Iannone (1987), suggest that Morrison does not take a<br />

“stand on the appall<strong>in</strong>g actions she depicts” (61), the statement of power beh<strong>in</strong>d Sula’s<br />

actions is explicit and attention-grabb<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

4. The consequences of accept<strong>in</strong>g mother<strong>in</strong>g as a biological imperative was handled<br />

nicely <strong>in</strong> Henderson (2009), <strong>in</strong> that the author offered a reunderstand<strong>in</strong>g of the def<strong>in</strong>ition<br />

of a so-called “good” mother, especially <strong>in</strong> terms of parent<strong>in</strong>g away from biological<br />

children.<br />

5. Aga<strong>in</strong>, Henderson’s 2009 work <strong>in</strong> BWGF is helpful as her <strong>in</strong>terviews “enhance our<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>gs of maternal absence by mov<strong>in</strong>g away from a selfish act of child rejection<br />

to a lov<strong>in</strong>g attempt to ‘do what’s best for the child’” (35).<br />

6. hooks’s concept of homeplace is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g the l<strong>in</strong>k between<br />

<strong>in</strong>timacy and violence with<strong>in</strong> the home.<br />

References<br />

Bouson, J. Brooks. Quiet as It’s Kept: Shame, Trauma, and Race <strong>in</strong> the Novels of <strong>Toni</strong> Morrison.<br />

Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000.<br />

Boyce Davies, Carole. Black Women, Writ<strong>in</strong>g and Identity: Migrations of the Subject. New<br />

York: Routledge, 1994.

fall 2011 / black women, gender, and families 43<br />

Henderson, Mae C. “Pathways to Fracture: African American Mothers and the Complexities<br />

of Maternal Absence.” Black Women, Gender, & Families 3, no. 2 (2009): 29–47.<br />

H<strong>in</strong>son, D. Scot. “Narrative and Community Crisis <strong>in</strong> Beloved.” MELUS 26, no. 4 (2001):147–<br />

67.<br />

hooks, bell. “Homeplace.” In Yearn<strong>in</strong>g: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, 41–49. Boston:<br />

South End Press, 1990.<br />

Iannone, Carol. “<strong>Toni</strong> Morrison’s Career.” Commentary 84, no. 6 (1987): 59–63.<br />

Morrison, <strong>Toni</strong>. Sula. New York: Plume/Pengu<strong>in</strong> Books USA, Inc., 1982. Orig<strong>in</strong>ally pub.<br />

1973.<br />

———. Beloved. New York: Plume/Pengu<strong>in</strong> Books USA Inc., 1988. Orig<strong>in</strong>ally pub. 1987.<br />

———. The Bluest Eye. New York: Plume/Pengu<strong>in</strong> Books USA, Inc., 1994. Orig<strong>in</strong>ally pub.<br />

1970.<br />

———. A Mercy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf/Random House, Inc, 2008.<br />

Peterson, Christopher. “Beloved’s Claim.” Modern Fiction Studies 52, no. 3 (2006):<br />

548–69.<br />

Russell, Kathy, Midge Wilson, and Ronald Hall. The Color Complex: The Politics of Sk<strong>in</strong><br />

Color among African Americans. New York: Doubleday, 1992.