Free Flow

oJhBl

oJhBl

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Economic Development and Water<br />

bio-mimicry, towards green infrastructure that organically integrates<br />

anthropogenic and natural features). The fundamental idea<br />

is a holistic rather than a fragmentary engagement with the task<br />

of managing resources. There is, after all the analysis, just one<br />

environment – not several. The urban and the natural are not as<br />

distinct as traditional thinking has assumed.<br />

The third and last pillar, cities with the social and institutional<br />

capital for sustainability, resilience, and liveability, stands united<br />

with the other pillars and in contradiction to superseded ways of<br />

thinking; but it demands a more extended explanation. While cities<br />

have long been condemned as alienating and alienated – prone to be<br />

characterized as inhuman blemishes on the landscape rather than as<br />

centres for human thriving – we can with at least equal justification<br />

celebrate, nurture and harness the social capital that is concentrated<br />

in the modern city. Cities are not simply the problem; the modern<br />

city’s emergent social properties make it a source of solutions. We<br />

encountered precursors of this idea above: according to the first<br />

pillar, cities have infrastructure that can be turned to use as new<br />

water catchments; and according to the second pillar, the urbanrural<br />

divide is best treated as artificial anyway, to be transcended for<br />

human purposes as much as for ‘natural’ ones. We saw how WSUD<br />

can work as a set of ‘urban design solutions’ for the provision of<br />

green infrastructure. Now we must extend the idea. Technology<br />

based on biophysical-science research alone cannot deliver, and<br />

our appreciation of the crucial role institutions play in sustainable<br />

resource usage is just beginning. We argue that unless new technologies<br />

are socially and institutionally embedded, their development<br />

will not yield complete solutions for urban water management. The<br />

social and institutional dimensions must be included in the holistic<br />

vision too, on an equal footing with technological initiatives.<br />

Insight in this area is elusive. The socio-institutional dimensions<br />

of WSUD, necessary for effective policy development and<br />

technology diffusion, need more research. Our analysis<br />

of the historical and socio-technical drivers of<br />

WSUD development across Melbourne (a city often<br />

identified as a WSUD leader, both nationally and<br />

internationally, especially for stormwater management)<br />

revealed that the deployment of WSUD in<br />

Melbourne has been the result of a complex interplay<br />

between key ‘champions’ (or change agents) and<br />

important local variables. In particular, the champions<br />

represent a small and informally connected<br />

group of individuals across government, academia<br />

and the development industry. These are the players<br />

who have pursued change from an ideology of best<br />

practice management, consistently underpinned<br />

by local developments in science and technology.<br />

Beyond the existence of champions, analysis revealed<br />

the involvement of instrumental variables – a<br />

mixture of historical accident and intentional advocacy<br />

outcomes such as the rise of environmentalism,<br />

external funding avenues and the establishment of<br />

a number of industry-focused cooperative research<br />

centres. The implications are well worth pursuing;<br />

but it is important now to highlight sustainability,<br />

resilience, and liveability – the desiderata mentioned<br />

in connection with the third pillar.<br />

Sustainability in the service of water sensitive cities<br />

demands a solid reserve of sociopolitical capital, and<br />

an assurance that citizens’ decision-making and behaviour<br />

are themselves water sensitive. It is a matter of<br />

education in the broadest sense: the community must<br />

value an ecologically sustainable lifestyle, with a<br />

heightened receptivity to necessary innovations, and<br />

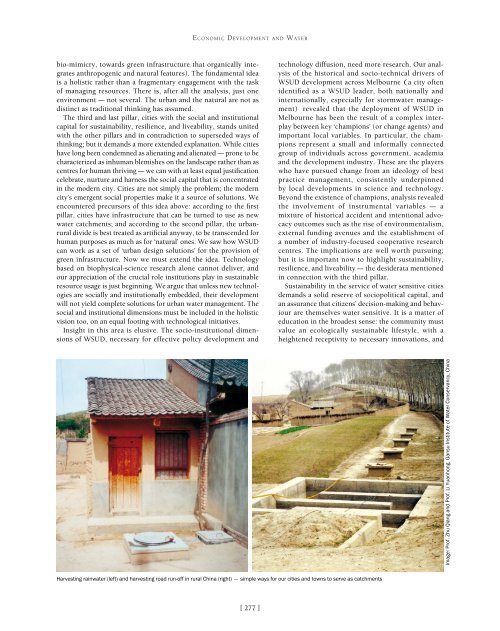

Image: Prof. Zhu Qiang and Prof. Li Yuanhong, Gansu Institute of Water Conservancy, China<br />

Harvesting rainwater (left) and harvesting road run-off in rural China (right) – simple ways for our cities and towns to serve as catchments<br />

[ 277 ]