You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

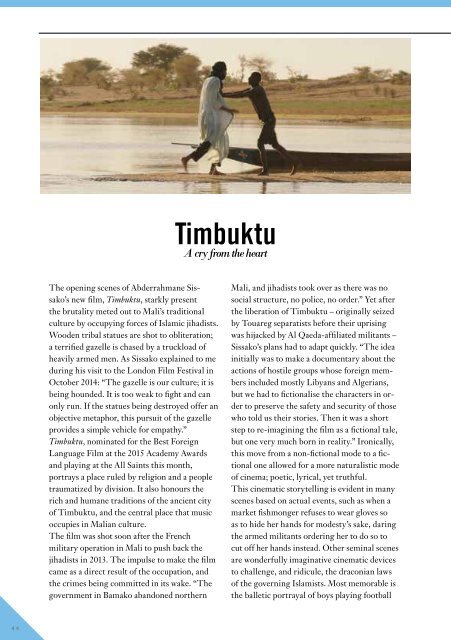

Timbuktu<br />

A cry from the heart<br />

The opening scenes of Abderrahmane Sissako’s<br />

new film, Timbuktu, starkly present<br />

the brutality meted out to Mali’s traditional<br />

culture by occupying forces of Islamic jihadists.<br />

Wooden tribal statues are shot to obliteration;<br />

a terrified gazelle is chased by a truckload of<br />

heavily armed men. As Sissako explained to me<br />

during his visit to the London Film Festival in<br />

October 2014: “The gazelle is our culture; it is<br />

being hounded. It is too weak to fight and can<br />

only run. If the statues being destroyed offer an<br />

objective metaphor, this pursuit of the gazelle<br />

provides a simple vehicle for empathy.”<br />

Timbuktu, nominated for the Best Foreign<br />

Language Film at the 2015 Academy Awards<br />

and playing at the All Saints this month,<br />

portrays a place ruled by religion and a people<br />

traumatized by division. It also honours the<br />

rich and humane traditions of the ancient city<br />

of Timbuktu, and the central place that music<br />

occupies in Malian culture.<br />

The film was shot soon after the French<br />

military operation in Mali to push back the<br />

jihadists in 2013. The impulse to make the film<br />

came as a direct result of the occupation, and<br />

the crimes being committed in its wake. “The<br />

government in Bamako abandoned northern<br />

Mali, and jihadists took over as there was no<br />

social structure, no police, no order.” Yet after<br />

the liberation of Timbuktu – originally seized<br />

by Touareg separatists before their uprising<br />

was hijacked by Al Qaeda-affiliated militants –<br />

Sissako’s plans had to adapt quickly. “The idea<br />

initially was to make a documentary about the<br />

actions of hostile groups whose foreign members<br />

included mostly Libyans and Algerians,<br />

but we had to fictionalise the characters in order<br />

to preserve the safety and security of those<br />

who told us their stories. Then it was a short<br />

step to re-imagining the film as a fictional tale,<br />

but one very much born in reality.” Ironically,<br />

this move from a non-fictional mode to a fictional<br />

one allowed for a more naturalistic mode<br />

of cinema; poetic, lyrical, yet truthful.<br />

This cinematic storytelling is evident in many<br />

scenes based on actual events, such as when a<br />

market fishmonger refuses to wear gloves so<br />

as to hide her hands for modesty’s sake, daring<br />

the armed militants ordering her to do so to<br />

cut off her hands instead. Other seminal scenes<br />

are wonderfully imaginative cinematic devices<br />

to challenge, and ridicule, the draconian laws<br />

of the governing Islamists. Most memorable is<br />

the balletic portrayal of boys playing football<br />

44