SUPREME COURT OF QUEENSLAND

QSC16-055

QSC16-055

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

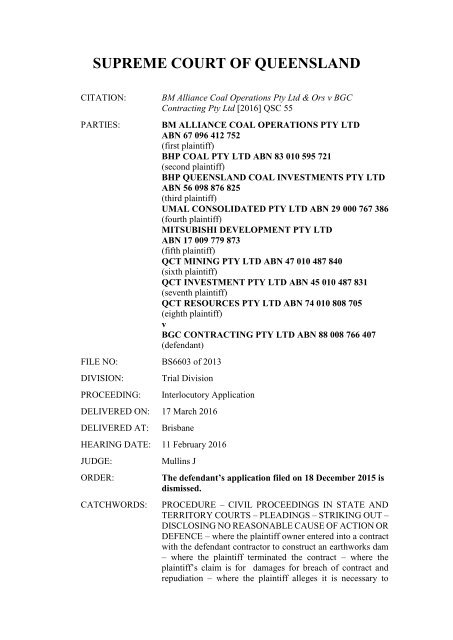

<strong>SUPREME</strong> <strong>COURT</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>QUEENSLAND</strong><br />

CITATION:<br />

PARTIES:<br />

FILE NO: BS6603 of 2013<br />

DIVISION:<br />

PROCEEDING:<br />

BM Alliance Coal Operations Pty Ltd & Ors v BGC<br />

Contracting Pty Ltd [2016] QSC 55<br />

BM ALLIANCE COAL OPERATIONS PTY LTD<br />

ABN 67 096 412 752<br />

(first plaintiff)<br />

BHP COAL PTY LTD ABN 83 010 595 721<br />

(second plaintiff)<br />

BHP <strong>QUEENSLAND</strong> COAL INVESTMENTS PTY LTD<br />

ABN 56 098 876 825<br />

(third plaintiff)<br />

UMAL CONSOLIDATED PTY LTD ABN 29 000 767 386<br />

(fourth plaintiff)<br />

MITSUBISHI DEVELOPMENT PTY LTD<br />

ABN 17 009 779 873<br />

(fifth plaintiff)<br />

QCT MINING PTY LTD ABN 47 010 487 840<br />

(sixth plaintiff)<br />

QCT INVESTMENT PTY LTD ABN 45 010 487 831<br />

(seventh plaintiff)<br />

QCT RESOURCES PTY LTD ABN 74 010 808 705<br />

(eighth plaintiff)<br />

v<br />

BGC CONTRACTING PTY LTD ABN 88 008 766 407<br />

(defendant)<br />

Trial Division<br />

Interlocutory Application<br />

DELIVERED ON: 17 March 2016<br />

DELIVERED AT:<br />

Brisbane<br />

HEARING DATE: 11 February 2016<br />

JUDGE:<br />

ORDER:<br />

CATCHWORDS:<br />

Mullins J<br />

The defendant’s application filed on 18 December 2015 is<br />

dismissed.<br />

PROCEDURE – CIVIL PROCEEDINGS IN STATE AND<br />

TERRITORY <strong>COURT</strong>S – PLEADINGS – STRIKING OUT –<br />

DISCLOSING NO REASONABLE CAUSE <strong>OF</strong> ACTION OR<br />

DEFENCE – where the plaintiff owner entered into a contract<br />

with the defendant contractor to construct an earthworks dam<br />

– where the plaintiff terminated the contract – where the<br />

plaintiff’s claim is for damages for breach of contract and<br />

repudiation – where the plaintiff alleges it is necessary to

2<br />

rectify the defendant’s breaches of the contract specified in the<br />

statement of claim and claims the costs of rectification as loss<br />

and damage – where the defendant applies to strike out<br />

paragraphs of the plaintiff’s statement of claim on the basis<br />

that the paragraphs failed to assert a causal nexus between the<br />

alleged breaches and the items of loss or damage – where the<br />

plaintiff relies on the application of the “ruling principle” for<br />

the assessment of damages for breach of contract – whether<br />

sufficient material facts are pleaded by the plaintiff to support<br />

the cause of action for damages for breach of contract<br />

COUNSEL:<br />

SOLICITORS:<br />

Bellgrove v Eldridge (1954) 90 CLR 613, considered<br />

Clark v Macourt (2013) 253 CLR 1; [2013] HCA 56,<br />

considered<br />

Mainteck Services Pty Ltd v Stein Heurtey SA (2014) 310<br />

ALR 113, considered<br />

Tabcorp Holdings Ltd v Bowen Investments Pty Ltd (2009)<br />

236 CLR 272; [2009] HCA 8, considered<br />

Willshee v Westcourt Ltd [2009] WASCA 87, considered<br />

G Beacham QC with B O’Brien for the plaintiffs<br />

R A Holt QC with L Clark for the defendant<br />

Herbert Smith Freehills for the applicants<br />

McCullough Robertson Lawyers for the defendant<br />

[1] The defendant applies to strike out paragraphs 19 to 23 of the plaintiffs’ statement of<br />

claim filed on 23 April 2015 or, in the alternative, for an order that the plaintiffs provide<br />

further and better particulars in respect of paragraphs 19(d) and 20 to 22. The application<br />

is opposed on behalf of the plaintiffs. There is a dispute between the parties as to what<br />

material facts must be pleaded in respect of the plaintiffs’ claim for damages for breach<br />

of contract arising from works performed by the defendant (an earthworks contractor) in<br />

constructing an earthworks dam and associated works at Goonyella Riverside Mine near<br />

Moranbah.<br />

Background to plaintiffs’ claim<br />

[2] The plaintiffs are joint venture parties which own the mine and the first plaintiff is the<br />

management company which operates the mine for them. The relevant contract was<br />

entered into between the first plaintiff and the defendant in December 2010. In December<br />

2011 the first plaintiff terminated the contract. At the time the termination took effect in<br />

January 2012, the construction of the dam was incomplete.<br />

[3] This proceeding was commenced by the plaintiffs in July 2013 claiming damages for<br />

breach of contract and repudiation. The breaches alleged in paragraphs 14 to 18 of the<br />

statement of claim are the placement of “lots” of soil in the embankment of the dam which<br />

do not comply with the specifications in the contract, along with the late delivery or nondelivery<br />

of the test results and reports required under the contract which were required to

3<br />

demonstrate the compliance of the lots with the specifications. The plaintiffs seek the<br />

costs of rectifying the non-compliant lots and the additional costs of completing the dam.<br />

Progress of the pleadings<br />

[4] Paragraph 19 of the statement of claim (omitting the particulars) alleges:<br />

“19. By reason of the breaches of the Contract set out above:<br />

(a) The soil placed in the Embankment in the areas<br />

described in paragraph 14 above does not comply with<br />

the requirements of the Contract;<br />

(b) The first plaintiff cannot determine whether the soil<br />

placed in the Embankment in the areas described in<br />

paragraph 15 above complies with the Contract;<br />

(c) The first plaintiff did not become aware of the matters<br />

set out in (a) and (b) above, until further soil had been<br />

placed in the Embankment on top of the areas which<br />

suffer from the deficiencies described in (a) and (b)<br />

above;<br />

(d) The work performed under the Contract does not<br />

comply with the Contract.”<br />

[5] Paragraph 20 then pleads that by reason of the defendant’s breaches of contract referred<br />

to in paragraphs 14 to 18, the first plaintiff has suffered loss and damage, the measure of<br />

which is the cost of rectifying the breaches referred to in paragraphs 14 and 15, or<br />

alternatively 14 and 16. Paragraph 21 contains an alternative pleading on the basis that<br />

it is the joint venture parties which have suffered the loss and damage and the first plaintiff<br />

is entitled to sue for and recover that loss for the benefit of the joint venture parties.<br />

[6] Paragraph 22 then sets out what the plaintiffs allege is necessary to be done in order to<br />

rectify the breaches in these terms:<br />

“In order to rectify the breaches referred to in paragraphs 14 and 15, or<br />

alternatively 14 and 16, above, it is necessary to:<br />

(a) remove the work performed by the defendant that does not comply with<br />

the Contract, and re-perform that work in accordance with the Contract<br />

(Cost of Rectification);<br />

(b) alternatively:<br />

(i) alter the batter of the upstream shoulder from 1V:3H to<br />

1V:4H, and install a HDPE liner to the upstream shoulder and<br />

the floor of the Dam impoundment area (Alternative Cost of<br />

Rectification Option 1);<br />

(ii) alter the batter of the upstream shoulder from 1V:3H to<br />

1V:4H, completely remove and replace the downstream

4<br />

shoulder and increase the thickness of the filter blanket layer<br />

(Alternative Cost of Rectification Option 2).”<br />

[7] The respective costs of the rectification works are alleged in paragraph 23.<br />

[8] The defendant has pleaded to the respective allegations made in paragraphs 14 to 18 of<br />

the statement of claim and in paragraph 21 of the defence denies each of the allegations<br />

alleged in paragraph 19 of the statement of claim.<br />

[9] In paragraph 22 of the defence, the defendant responds to paragraph 20 of the statement<br />

of claim (on the assumption the defendant breached the contract as alleged by the first<br />

plaintiff) in these terms:<br />

“(a) no loss was suffered by the first plaintiff;<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

(d)<br />

(e)<br />

the pleaded breaches of contract did not render the Dam (so far as<br />

completed to the time of termination) unfit for its intended purpose;<br />

the pleaded breaches of contract do not justify the expense, time and<br />

effort of demolishing and rebuilding the Dam;<br />

the time and cost involved in demolishing and rebuilding the Dam<br />

would be out of all proportion to the benefit gained;<br />

in the premises, demolishing and rebuilding the Dam is not a reasonable<br />

response to the pleaded breaches of contract.”<br />

[10] The same allegations are made by the defendant in paragraph 23 of the defence in<br />

response to paragraph 21(a) of the statement of claim.<br />

[11] In paragraph 24 of the defence, the defendant denies the allegations pleaded in paragraph<br />

22 of the statement of claim on the basis that it is not necessary for the plaintiff to<br />

undertake any of the work pleaded in paragraph 22 as a consequence of the defendant’s<br />

performance of the contract and alleges that any requirement to re-perform work<br />

performed by the defendant had been caused by the matters that are then set out in<br />

paragraph 24(b) of the defence.<br />

[12] There is a detailed response by the plaintiffs to paragraphs 22 and 23 of the defence which<br />

is set out in paragraph 24A of the reply. In particular, the plaintiffs pleaded in paragraph<br />

24A(b) that:<br />

“(b) in relation to paragraph 22(b) and 23(a)(ii) the plaintiffs:<br />

(i)<br />

(ii)<br />

say that the consequence of the breaches of contract set out<br />

in the further amended statement of claim is that the Dam<br />

could not be certified for use;<br />

deny the allegation and believe it to be untrue because of<br />

the material fact set out in sub-paragraph (i) above;”<br />

The defendant’s complaint

5<br />

[13] The defendant’s main complaint about paragraphs 19 to 23 of the statement of claim is<br />

that there is a failure to assert a causal nexus linking each alleged breach of contract in<br />

paragraphs 14 to 18 of the statement of claim with the loss and damage flowing from each<br />

breach.<br />

[14] The plaintiffs rely on Bellgrove v Eldridge (1954) 90 CLR 613 to assert in response that<br />

no further facts need be pleaded as the first plaintiff is entitled to insist upon performance<br />

of the contract and adherence to the standards of construction required by the contract<br />

and the loss for a failure to comply with those standards is the sum of money required to<br />

make the work conform with the contractual standard.<br />

[15] On the strike out application, the issue is whether, in respect of a cause of action for<br />

damages for breach of a contract, it is necessary for the plaintiffs to plead any additional<br />

material facts in the statement of claim showing the causal link between the acts<br />

complained of and the loss claimed.<br />

[16] Both parties’ submissions addressed authorities relevant to identifying the material facts<br />

to be established to recover damages for breach of contract. It is appropriate therefore to<br />

consider the effect of these authorities.<br />

The relevant authorities<br />

[17] In Bellgrove the defendant owner counterclaimed against the plaintiff builder for breach<br />

of the building contract and claimed damages on the basis the house was worthless. The<br />

trial judge had found that there had been “a very substantial departure from the<br />

specifications” that resulted “in grave instability in the building”. The issue before the<br />

trial judge was whether there was available for remedying the defect in the construction<br />

of the foundations any practical solution other than the demolition of the building and its<br />

re-erection in accordance with the plans and specifications. Judgment was given for the<br />

defendant for the amount that represented the cost of demolishing and re-erecting the<br />

building in accordance with the plans and specifications together with certain<br />

consequential losses less the demolition value of the house and moneys unpaid under the<br />

contract.<br />

[18] The court observed at 617:<br />

“In the present case, the respondent was entitled to have a building erected<br />

upon her land in accordance with the contract and the plans and specifications<br />

which formed part of it, and her damage is the loss which she has sustained<br />

by the failure of the appellant to perform his obligation to her. This loss<br />

cannot be measured by comparing the value of the building which has been<br />

erected with the value it would have borne if erected in accordance with the<br />

contract; her loss can, prima facie, be measured only by ascertaining the<br />

amount required to rectify the defects complained of and so give to her the<br />

equivalent of a building on her land which is substantially in accordance with<br />

the contract.”<br />

[19] It is apparent from the discussion by the court of the assessment of damages in Bellgrove<br />

that it was a question of fact as to what work was necessary to remedy the defects in the

6<br />

building to produce conformity with the plans and specifications and that not every breach<br />

of a building contract requires the removal or demolition of some part of the structure.<br />

The court noted at 618, as was held to be the position in Bellgrove, “there may well be<br />

cases where the only practicable method of producing conformity with plans and<br />

specifications is by demolishing the whole of the building and erecting another in its<br />

place”.<br />

[20] The court noted a qualification of reasonableness to the rule that the measure of damages<br />

is the cost of the remedial work required to achieve conformity with the plans and<br />

specifications in these terms, at 618:<br />

“The qualification, however, to which this rule is subject is that, not only must<br />

the work undertaken be necessary to produce conformity, but that also, it must<br />

be a reasonable course to adopt.”<br />

[21] Bellgrove was considered by the High Court in Tabcorp Holdings Ltd v Bowen<br />

Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 236 CLR 272 which concerned the measure of damages<br />

recoverable by a landlord for the breach by the tenant of clause 2.13 of the lease of<br />

business premises pursuant to which the tenant had covenanted not to make, or permit to<br />

be made, any substantial alteration or addition to the demised premises, without the prior<br />

written approval of the landlord (which consent was not to be unreasonably withheld or<br />

delayed). The lease was for a term of 10 years that commenced on 1 February 1997.<br />

Without the permission of the landlord, the tenant in July 1997 commenced a massive<br />

refurbishment of the foyer which resulted in the removal of the existing foyer and the<br />

construction of a high quality foyer made from granite. At first instance, judgment was<br />

given for the landlord for damages of $34,820 which was assessed at the diminution in<br />

the value of the building for breach of clause 2.13. The landlord successfully appealed<br />

to the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia and was awarded damages by the<br />

majority of $1.38m based on the cost of reinstatement approach. The appeal to the High<br />

Court was unsuccessful.<br />

[22] The judgment of the High Court at [12] noted that clause 2.13 was an express negative<br />

covenant that served “a function of considerable practicable utility in relation to the<br />

Landlord’s capacity to protect its legitimate interest in preserving the physical character<br />

of the premises leased.” The court also noted at [12] that the landlord would have been<br />

able to obtain the assistance of equitable remedies to prevent a substantial alteration being<br />

made to the premises by the tenant without prior written consent. In respect of the tenant’s<br />

submission that the appropriate measure of damages was the diminution in value of the<br />

reversion, the court observed at [13]:<br />

“The assumption underlying the Tenant’s submission takes no account of the<br />

existence of equitable remedies, like decrees of specific performance and<br />

injunction, which ensure or encourage the performance of contracts rather<br />

than the payment of damages for breach. It is an assumption which underrates<br />

the extent to which those remedies are available. However, even if the<br />

assumption were correct it would not assist the Tenant. The Tenant’s<br />

submission misunderstands the common law in relation to damages for breach<br />

of contract. The ‘ruling principle’, confirmed in this Court on numerous<br />

occasions, with respect to damages at common law for breach of contract is<br />

that stated by Parke B in Robinson v Harman:

7<br />

‘The rule of the common law is, that where a party sustains a loss<br />

by reason of a breach of contract, he is, so far as money can do it,<br />

to be placed in the same situation, with respect to damages, as if<br />

the contract had been performed’.” (footnotes omitted)<br />

[23] The court therefore held at [15] that “the Landlord was contractually entitled to the<br />

preservation of the premises without alterations not consented to; its measure of damages<br />

is the loss sustained by the failure of the Tenant to perform that obligation; and that loss<br />

is the cost of restoring the premises to the condition in which they would have been if the<br />

obligation had not been breached”. The court also noted at [15] the similar approach of<br />

the court in Bellgrove at 617.<br />

[24] The tenant relied on the qualification referred to in Bellgrove. The court noted, however,<br />

that on the basis of the example which the court in Bellgrove had given at 618 of when<br />

the qualification to the ruling principle would apply that it tended “to indicate that the test<br />

of ‘unreasonableness’ is only to be satisfied by fairly exceptional circumstances. It was<br />

also noted at [17] that the “reasonableness” exception was not found to exist in Bellgrove<br />

and nothing in the reasoning in Bellgrove suggested that the course which the landlord<br />

proposed in Tabcorp was unnecessary or unreasonable.<br />

[25] The court in Tabcorp concluded at [19]-[20]:<br />

“[19] Further, the Landlord correctly submitted that the Tenant’s submission<br />

misconstrued what this Court said in Bellgrove v Eldridge. The<br />

‘qualification’ referred to in the passage quoted above that the ‘work<br />

undertaken be necessary to produce conformity’ meant, in that case, apt<br />

to conform with the plans and specifications which had not been<br />

conformed with. Applied to this case, the expression ‘necessary to<br />

produce conformity’ means ‘apt to bring about conformity between the<br />

foyer as it would become after the damages had been spent in rebuilding<br />

it and the foyer as it was at the start of the lease’. And the Landlord also<br />

correctly submitted that the requirement of reasonableness did not mean<br />

that any excess over the amount recoverable on a diminution in value<br />

was unreasonable. The Tenant’s submissions rested on a loose principle<br />

of ‘reasonableness’ which would radically undercut the bargain which<br />

the innocent party had contracted for and make it very difficult to<br />

determine in any particular case on what basis damages would be<br />

assessed. That principle should not be accepted.<br />

[20] If the benefit of the covenant in cl 2.13 were to be secured to the<br />

Landlord, it is necessary that reinstatement damages be paid, and it is<br />

not unreasonable for the Landlord to insist on their payment.”<br />

(footnotes omitted)<br />

[26] Bellgrove therefore remains authoritative for the application of the ruling principle where<br />

a builder breaches a contract by substantially departing from the specifications.<br />

[27] Both Bellgrove and Tabcorp were applied in Willshee v Westcourt Ltd [2009] WASCA<br />

87. There was an implied term in the building contract for a house that the limestone for<br />

the external cladding would be of high quality. The owner Mr Willshee claimed that the

8<br />

builder Westcourt breached that term by using inferior or second quality limestone. That<br />

claim was upheld, but Mr Willshee was awarded damages by the trial judge only for the<br />

cost of cleaning and sealing the limestone and some repainting. Mr Willshee succeeded<br />

on appeal to recover damages for the amount required to put him in the position of having<br />

a house constructed using limestone which was of high quality. The damages reflected<br />

the cost of demolishing the exterior wall and replacing it with limestone which was of<br />

high quality. In considering the application of the qualification of unreasonableness,<br />

Martin CJ (with whom the other members of the court agreed) at [70] found that<br />

Westcourt’s breach “was a serious and significant breach, which had a significant impact<br />

upon the rate at which the external cladding of the house weathered and deteriorated, and<br />

which has had a significant impact upon the appearance of the house”. It was also noted<br />

by Martin CJ at [72] that the party wishing to rely upon the qualification to the “ruling<br />

principle” of damages carries the onus of proving the facts relevant to its application.<br />

[28] Tabcorp was followed in Clark v Macourt (2013) 253 CLR 1, in which the ruling<br />

principle was applied in assessing damages for breach of warranty in respect of some of<br />

the assets that were sold by the vendor company to Dr Clark. Dr Clark had agreed to<br />

purchase from the vendor company the assets attached to an artificial reproductive<br />

technology business including frozen sperm. The vendor warranted that it would provide<br />

Dr Clark records for the frozen sperm that complied with specified guidelines. Of the<br />

3,513 straws of frozen sperm that were delivered, only 504 of those had compliant records<br />

and were therefore usable by Dr Clark in her artificial reproductive technology business.<br />

Dr Clark therefore had to acquire usable frozen sperm from a supplier in the United States.<br />

She charged her patients a fee which covered the costs in acquiring the usable frozen<br />

sperm from the United States. The parties agreed that Dr Clark should have expected to<br />

receive, in accordance with the warranty, an additional 1,996 compliant and usable sperm<br />

straws, apart from the 504 that were usable. At first instance damages were assessed at<br />

almost $1.3m as the value of the 1,996 compliant sperm straws as at the date of<br />

completion. The appeal had been allowed by the New South Wales Court of Appeal on<br />

the basis that Dr Clark had suffered no loss. Dr Clark appealed to the High Court.<br />

[29] By majority, the High Court allowed the appeal and reinstated the assessment of damages<br />

at first instance on the basis that damages for breach of contract were to put the promisee,<br />

so far as money could do it, in the same situation, as if the contract had been performed<br />

as promised (at [7], [26] and [106]). As damages were assessed at the date of breach and<br />

not at the date of trial, the subsequent dealings by Dr Clark left her neither better nor<br />

worse off than she was before she undertook the transactions (at [19], [37] and [128]-<br />

[129]).<br />

[30] The majority were therefore in agreement that the ruling principle governed the<br />

assessment of damages. Keane J noted at [107] that in Bellgrove the court at 617-618<br />

“explained that the practical operation of the ruling principle may vary depending on the<br />

commercial context; but that the principle is always applied with a view to assuring to the<br />

purchaser the monetary value of faithful performance by the vendor of the bargain”.<br />

Keane J then stated at [109]:<br />

“The value to be paid in accordance with the ruling principle is assessed at<br />

the date of breach of contract, not as a matter of discretion, but as an integral<br />

aspect of the principle, which is concerned to give the purchaser the economic<br />

value of the performance of the contract at the time that performance was

9<br />

promised. In this way, the measure of damages captures for the purchaser the<br />

benefit of the bargain and so compensates the purchaser for the loss of that<br />

benefit. (footnote omitted)<br />

[31] The defendant relies on a statement made by Leeming JA (with whom the other members<br />

of the court agreed) in Mainteck Services Pty Ltd v Stein Heurtey SA (2014) 310 ALR<br />

113 in dealing with what the plaintiff in a building case must prove to establish damages<br />

for breach of contract where there is a “global claim” for damages. Leeming JA<br />

confirmed at [186] that “there are no special legal principles that mean the plaintiffs in<br />

‘building cases’ win or lose differently from plaintiffs in other classes of contractual<br />

case”. Leeming JA then stated at [187]-[188]:<br />

“[187] A plaintiff seeking damages will fail unless he, she or it establishes<br />

breach, causation and loss.<br />

[188] True it is that some decisions on breach of contract in building cases<br />

have used the language of ‘global claim’. Contrary to what was at<br />

the forefront of Mainteck’s written and oral submissions, this does<br />

not involve any special principles of fact or of law.”<br />

[32] There is nothing in these general observations by Leeming JA in Mainteck which detract<br />

from the authority of Bellgrove and Tabcorp in the application of the ruling principle to<br />

the assessment of damages for breach of contract.<br />

Are all material facts pleaded in the statement of claim?<br />

[33] The plaintiffs are not required to plead that they are seeking for the damages to be<br />

assessed by the application of the ruling principle, as that is law that applies to the<br />

plaintiffs’ claim in accordance with the relevant authorities. A subsidiary complaint<br />

which the defendant’s solicitors had made in the r 444 letter dated 12 November 2015<br />

was that for the costs of rectification work to be recoverable as damages for breach as the<br />

plaintiffs had pleaded in their statement of claim “the dam must have been deficient in<br />

some way as a result of the alleged breaches” and asserted that the plaintiffs need to plead<br />

that each of those breaches created a deficiency in the dam and what the deficiency was.<br />

In similar vein, the defendant submitted on this application that no practical consequence<br />

from any defect in the dam, such as the dam not being reasonably fit for its purpose, is<br />

pleaded. The subsidiary point raised by the defendant is not supported by the relevant<br />

authorities.<br />

[34] In a claim for damages for breach of a construction contract in reliance on Bellgrove, the<br />

statement of claim must plead the relevant provisions of the contract, identify the breaches<br />

and then plead the action the plaintiffs assert must be taken to rectify the breaches to<br />

achieve conformity with the contract. This must be followed by the specification of the<br />

loss and damage arising from the costs of rectification.<br />

[35] The defendant’s submission which is critical of paragraph 20 (and also paragraph 21) of<br />

the statement of claim asserts that these are the paragraphs alleging loss and damage<br />

arising from the alleged breaches and that no attempt is made by the plaintiffs to identify<br />

or plead the causal nexus between breaches and the alleged loss and damage.

10<br />

[36] It is a mistake to focus on paragraphs 20 and 21 of the statement of claim, without having<br />

regard to the allegation in paragraph 22. It is worth observing that paragraphs 20 and 21<br />

appear to be out of order with paragraph 22.<br />

[37] It is paragraph 22 in which the allegation is made that in order to rectify the breaches<br />

referred to in paragraphs 14 and 15 (or 14 and 16) it is necessary to remove the work<br />

performed by the defendant that did not comply with the contract and re-perform the work<br />

in accordance with the contract which is described as the cost of rectification. Two<br />

alternative methods of rectification are then pleaded in paragraph 22(b). Paragraph 20<br />

(and therefore paragraph 21) logically follow with the claim for that cost of rectification<br />

as the loss and damage for the breaches of the contract. The qualification of the<br />

reasonableness of the proposed rectification as an issue has then been raised in paragraph<br />

22(e) of the defence, as contemplated by Willshee at [72].<br />

[38] The defendant’s complaint that the plaintiffs should plead a causal nexus between each<br />

alleged breach of contract with a particular item of loss or damage is unfounded, when<br />

the plaintiffs are seeking to recover the cost of the work that is necessary to remedy all<br />

the non-compliances with the contract, so that the first plaintiff is in the position, as if the<br />

contract had been performed as promised.<br />

[39] The defendant’s complaints about paragraphs 19 to 23 of the statement of claim are<br />

misconceived in light of the plaintiffs’ reliance on the application of the ruling principle<br />

to the assessment for damages for breach of contract. All material facts to support the<br />

claim have been pleaded. The application to strike out paragraphs 19 to 23 of the<br />

statement of claim cannot succeed.<br />

Request for particulars<br />

[40] In respect of paragraphs 19(d), the defendant seeks full particulars of the “work performed<br />

under the Contract” which is said not to comply with the contract. That request takes<br />

paragraph 19(d) out of context. It is the conclusion to the pleading of the other matters<br />

in paragraphs 19(a), (b) and (c). Paragraph 19 has otherwise been previously<br />

particularised in an adequate manner.<br />

[41] The request for further particulars of paragraphs 20 and 21 of the statement of claim in<br />

respect of the loss and damage alleged to have been caused by each of the defendant’s<br />

alleged breaches of contract is misconceived in light of the reliance by the plaintiffs on<br />

the application of the ruling principle. For the same reason the defendant’s request in<br />

respect of the facts, matters, circumstances and things relied on by the plaintiffs in support<br />

of the allegation that the alleged necessity to rectify was caused by the alleged breaches<br />

is also misconceived. The balance of the particulars that are sought in respect of<br />

paragraph 22 of the statement of claim is in respect of matters that have already been<br />

sufficiently pleaded and particularised by reference to the breaches referred to in<br />

paragraphs 14 and 15 (or 14 and 16) of the statement of claim. The request for particulars<br />

appears to have been drafted, without considering the content and context of the other<br />

relevant paragraphs in the statement of claim.

11<br />

[42] The alternative claim in the application for an order for further and better particulars must<br />

also fail.<br />

Orders<br />

[43] It follows that the defendant’s application filed on 18 December 2015 must be dismissed.<br />

[44] Subject to hearing submissions from the parties, I consider that costs should follow the<br />

event.