MIGRATION

OCR-A-Migration-sample-chapter

OCR-A-Migration-sample-chapter

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1 Migration in the Middle Ages c1000–c1500 1.3 England’s immigrants in the Middle Ages<br />

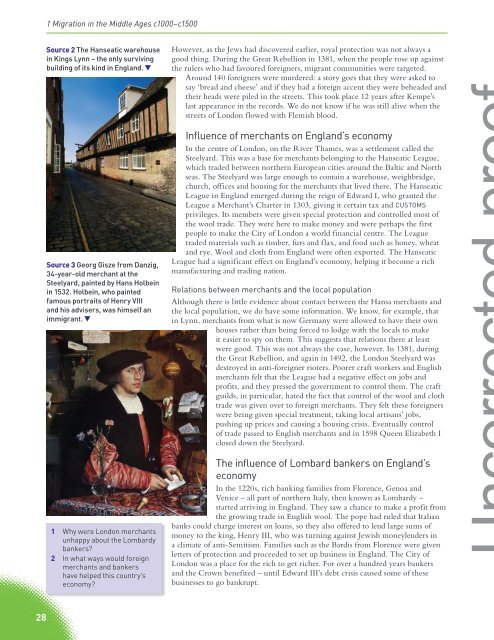

Source 2 The Hanseatic warehouse<br />

in Kings Lynn – the only surviving<br />

building of its kind in England.<br />

Source 3 Georg Gisze from Danzig,<br />

34-year-old merchant at the<br />

Steelyard, painted by Hans Holbein<br />

in 1532. Holbein, who painted<br />

famous portraits of Henry VIII<br />

and his advisers, was himself an<br />

immigrant.<br />

1 Why were London merchants<br />

unhappy about the Lombardy<br />

bankers?<br />

2 In what ways would foreign<br />

merchants and bankers<br />

have helped this country’s<br />

economy?<br />

However, as the Jews had discovered earlier, royal protection was not always a<br />

good thing. During the Great Rebellion in 1381, when the people rose up against<br />

the rulers who had favoured foreigners, migrant communities were targeted.<br />

Around 140 foreigners were murdered: a story goes that they were asked to<br />

say ‘bread and cheese’ and if they had a foreign accent they were beheaded and<br />

their heads were piled in the streets. This took place 12 years after Kempe’s<br />

last appearance in the records. We do not know if he was still alive when the<br />

streets of London flowed with Flemish blood.<br />

Influence of merchants on England’s economy<br />

In the centre of London, on the River Thames, was a settlement called the<br />

Steelyard. This was a base for merchants belonging to the Hanseatic League,<br />

which traded between northern European cities around the Baltic and North<br />

seas. The Steelyard was large enough to contain a warehouse, weighbridge,<br />

church, offices and housing for the merchants that lived there. The Hanseatic<br />

League in England emerged during the reign of Edward I, who granted the<br />

League a Merchant’s Charter in 1303, giving it certain tax and CUSTOMS<br />

privileges. Its members were given special protection and controlled most of<br />

the wool trade. They were here to make money and were perhaps the first<br />

people to make the City of London a world financial centre. The League<br />

traded materials such as timber, furs and flax, and food such as honey, wheat<br />

and rye. Wool and cloth from England were often exported. The Hanseatic<br />

League had a significant effect on England’s economy, helping it become a rich<br />

manufacturing and trading nation.<br />

Relations between merchants and the local population<br />

Although there is little evidence about contact between the Hansa merchants and<br />

the local population, we do have some information. We know, for example, that<br />

in Lynn, merchants from what is now Germany were allowed to have their own<br />

houses rather than being forced to lodge with the locals to make<br />

it easier to spy on them. This suggests that relations there at least<br />

were good. This was not always the case, however. In 1381, during<br />

the Great Rebellion, and again in 1492, the London Steelyard was<br />

destroyed in anti-foreigner rioters. Poorer craft workers and English<br />

merchants felt that the League had a negative effect on jobs and<br />

profits, and they pressed the government to control them. The craft<br />

guilds, in particular, hated the fact that control of the wool and cloth<br />

trade was given over to foreign merchants. They felt these foreigners<br />

were being given special treatment, taking local artisans’ jobs,<br />

pushing up prices and causing a housing crisis. Eventually control<br />

of trade passed to English merchants and in 1598 Queen Elizabeth I<br />

closed down the Steelyard.<br />

The influence of Lombard bankers on England’s<br />

economy<br />

In the 1220s, rich banking families from Florence, Genoa and<br />

Venice – all part of northern Italy, then known as Lombardy –<br />

started arriving in England. They saw a chance to make a profit from<br />

the growing trade in English wool. The pope had ruled that Italian<br />

banks could charge interest on loans, so they also offered to lend large sums of<br />

money to the king, Henry III, who was turning against Jewish moneylenders in<br />

a climate of anti-Semitism. Families such as the Bardis from Florence were given<br />

letters of protection and proceeded to set up business in England. The City of<br />

London was a place for the rich to get richer. For over a hundred years bankers<br />

and the Crown benefited – until Edward III’s debt crisis caused some of these<br />

businesses to go bankrupt.<br />

Uncorrected proof<br />

Source 4 Bristol’s tax rolls.<br />

3 Why are the aliens registers<br />

a valuable source of<br />

information for historians?<br />

Source 5 A modern map from the<br />

England’s Immigrants website,<br />

showing numbers of foreign<br />

migrants in Kent between 1440<br />

and 1550 and where they lived,<br />

according to the aliens register. As<br />

the tax records were not complete,<br />

the actual numbers will have been<br />

higher.<br />

4 What does the map in Source<br />

5 suggest about the way<br />

immigrants were received in<br />

England?<br />

Relations between bankers and the local population<br />

London merchants did not welcome foreign merchants and bankers, and regularly<br />

demanded controls and restrictions on them – sometimes with success. Foreigners<br />

were also often disliked by the general public, who felt that they would simply<br />

make their money then leave. In fact, the money the foreign merchants invested<br />

helped boost England’s economy in many ways, encouraging trade and building<br />

works as well as financing foreign wars. The City of London’s status as a world<br />

financial centre began at this time, and many of the words we use about money,<br />

including ‘bank’, ‘credit’ and ‘debit’, come from Italian. The £ symbol is from the<br />

initial letter ‘l’ of the Italian word for pound.<br />

Sources of information about England’s medieval<br />

immigrants<br />

In the late Middle Ages, about one in every 100 people in England was foreign<br />

born; in London it was six in every 100. We know their stories because<br />

governments imposed taxes called ALIENS REGISTERS on those who were born<br />

outside the king’s realm. These were set up partly to collect money for war and<br />

partly to respond to complaints about foreigners. Thanks to these tax records<br />

we know the names of most immigrants, their occupations and where they<br />

came from.<br />

ACTIVITY<br />

What do the tax records reveal?<br />

The tax records do not give us a full<br />

picture. To begin with they seldom<br />

mention women. They are also much more<br />

detailed in some places than others. They<br />

only list people born outside England, so<br />

second- or third-generation immigrants<br />

are not shown. As they do not record<br />

religion or ethnicity, there is a lot that we<br />

do not know about the people listed – for<br />

example whether any of them came from<br />

beyond Europe. The tax records also<br />

cannot tell us what immigrants thought,<br />

felt or experienced. However, we do get<br />

a window into the lives of immigrants<br />

that we do not gain from the information<br />

written by the rich and powerful.<br />

Look up the England’s Immigrants project at www.englandsimmigrants.com.<br />

Search the database and find out who was living in your city, town or village in 1300,<br />

1450 and 1600. Find where they migrated from and what their occupations were.<br />

What similarities and differences can you find?<br />

Create one of the following:<br />

– a presentation about medieval migration to your area, supported by maps, charts<br />

and graphs you have created using the database<br />

– a ‘time traveller’ story similar to the one about Bristol in the Introduction<br />

– a poster describing medieval migration to your local area, to be displayed publicly<br />

in your school<br />

– a migration tourist trail, if there are still traces in your area of medieval<br />

migrations (historic buildings, street names, monuments etc.).<br />

28 29