You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

After working with Siegel for a while, Rieser received a business loan and moved<br />

into his own studio. He began working on advertising campaigns around town.<br />

“You go from making no money to doing well. I was learning on the fly,” Rieser<br />

said. Because of his work ethic, Rieser was able to sign with an agent in New<br />

York. He moved to Los Angeles around 2007 and was immersed in commercial<br />

work. But the industry in LA was inundated with photographers, which drove prices<br />

down and made it hard to live there.<br />

At the same time, Rieser suffered from a serious creative block. He felt he had<br />

reached a point where his work was just a reflection of other people’s ideas.<br />

In many ways, he had become a great technician, but the artistry seemed to<br />

elude him.<br />

Going Inward, Looking Back<br />

In response to this block, Rieser decided to strip everything down. He went<br />

minimal. No models. No crew. No stylists. Just him and his camera. He focused on<br />

listening and observing and trying to do more personal work. The two projects that<br />

emerged from this period were “The Class of 99 Turns 30” and “Starting Over.”<br />

The former documents his graduating class’ promised hope and juxtaposes this<br />

against the reality of unemployment and a housing crash. The series received<br />

American Photography Annual 26’s “Best Personal Work Series” award. “Starting<br />

Over” chronicles his parents pending move to Arizona from the house they lived in<br />

for 23 years.<br />

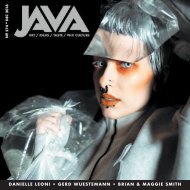

10 JAVA<br />

MAGAZINE<br />

“That project started almost in a context of me being selfish. I wanted to<br />

photograph the house I grew up in for my own reasons,” said Rieser. “Quickly<br />

thereafter, I realized it was much more about them and their loss.” Rieser learned a<br />

lot about his parents in the process. He saw them in vulnerable positions and<br />

experienced the transition from a parent-child relationship to a relationship of<br />

peers. Both of these projects mined the narrative in search of the deeper, less<br />

obvious truths. Both projects were studies in nostalgia and memory.<br />

“I feel estranged from my youth like everyone does,” said Rieser. “My idea of home<br />

doesn’t exist anymore. That idea has moved on. As much as you want to hold onto<br />

those notions, concepts and ideas—it’s just not there anymore.”<br />

In one gripping photo, Rieser’s father stands waist deep in a pool looking down<br />

into the water. His hands seem to be searching for something, in a sort of limbo<br />

right below the water. It’s a simple image that carries a lot of weight. This<br />

nostalgia and sense of memory moves a lot of Rieser’s photographs forward and<br />

backward. Photography is one of those art forms that both captures a moment at<br />

the same time speaks to a variety of moments and movements.<br />

The Motion of Nostalgia<br />

“I am very fascinated with memory, growing up and nostalgia—perspective<br />

and perception versus reality and truth. Where I grew up, it’s this strange space<br />

that’s familiar and foreign at the same time. Like a dream,” said Rieser. This very<br />

curiosity informed one of his most formative projects: “Christmas in America.”