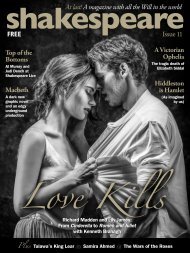

Shakespeare Magazine 07

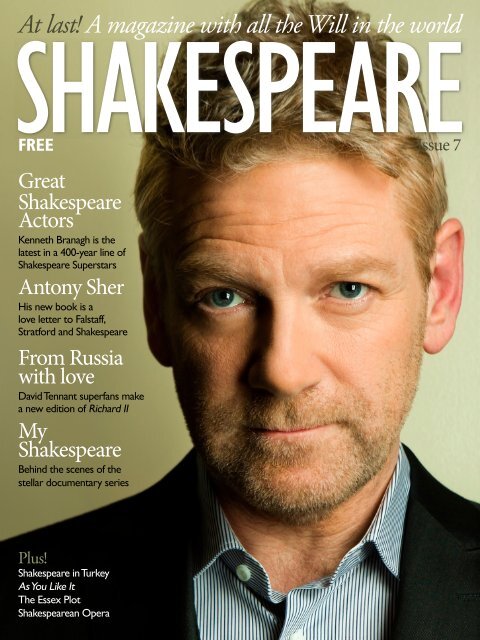

Kenneth Branagh is cover star of Shakespeare Magazine 07, as the issue's theme is Great Shakespeare Actors. Stanley Wells discusses his book on the subject, while Antony Sher reveals what it's like to play Falstaff. We also go behind the scenes of the My Shakespeare TV series, and Zoe Waites chats about playing Rosalind in the USA. Other highlights include Shakespeare in Turkey, Shakespeare Opera, and the real story of Shakespeare and the Essex Plot. All this, and the Russian fans who made their own edition of David Tennant's Richard II!

Kenneth Branagh is cover star of Shakespeare Magazine 07, as the issue's theme is Great Shakespeare Actors. Stanley Wells discusses his book on the subject, while Antony Sher reveals what it's like to play Falstaff. We also go behind the scenes of the My Shakespeare TV series, and Zoe Waites chats about playing Rosalind in the USA. Other highlights include Shakespeare in Turkey, Shakespeare Opera, and the real story of Shakespeare and the Essex Plot. All this, and the Russian fans who made their own edition of David Tennant's Richard II!

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

At last! A magazine with all the Will in the world<br />

SHAKESPEARE<br />

FREE<br />

Issue 7<br />

Great<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Actors<br />

Kenneth Branagh is the<br />

latest in a 400-year line of<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> Superstars<br />

Antony Sher<br />

His new book is a<br />

love letter to Falstaff,<br />

Stratford and <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

From Russia<br />

with love<br />

David Tennant superfans make<br />

a new edition of Richard II<br />

My<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Behind the scenes of the<br />

stellar documentary series<br />

Plus!<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> in Turkey<br />

As You Like It<br />

The Essex Plot<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>an Opera

The Folger <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Library is the world’s largest repository of <strong>Shakespeare</strong>ana<br />

and English Renaissance books, manuscripts, and objets d’art. Nobody alive knows<br />

<br />

it for 25 years. That’s why he is the perfect candidate to pull off an inside job and<br />

heist from the library’s underground bank vault a priceless artifact that can rock the<br />

foundation of English Literature...<br />

“Peterson’s novel is a lush tale of noir<br />

fiction in the spirit of the appealing<br />

thief utilizing all his wits against<br />

almost insurmountable odds.”<br />

Literary Fiction Book Review<br />

Published in the USA by Ram Press<br />

Available in paperback, Kindle, Audible Audio, and iTunes Editions<br />

On sale at Amazon.com, B&N, Books-A-Million, Indie Bound, et al

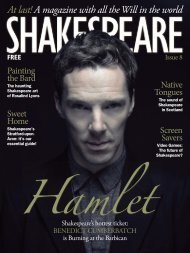

Welcome <br />

Welcome<br />

to Issue 7 of <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Photo: David Hammonds<br />

For many of us, the reason we get interested in<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> in the first place is because of actors.<br />

So it was only a matter of time before we ran an issue<br />

with the theme of Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Actors.<br />

As it happens, the venerable Stanley Wells has just published a book<br />

with that very title, so I hopped on a train to Stratford-upon-Avon to<br />

ask him what it really takes to rank among the very best.<br />

Not only that, I had the pleasure of interviewing Antony Sher, one<br />

of very few living actors – our cover star Kenneth Branagh is another –<br />

who feature in Stanley’s book. Antony told me about his experience of<br />

playing the mighty role of Falstaff, as documented in his warm-hearted<br />

and witty memoir Year of the Fat Knight.<br />

In addition, I had an enthralling, often hilarious conversation with<br />

Richard Denton, producer of the My <strong>Shakespeare</strong> TV series (which<br />

is fronted by A-List actors like Kim Cattrall, Hugh Bonneville and<br />

Morgan Freeman).<br />

This issue also features some wonderful contributions by writers<br />

from the UK, America, Turkey and Russia. Each article has enhanced<br />

my understanding of <strong>Shakespeare</strong> and brought a smile to my face – I<br />

hope this is the case for you too.<br />

As always, <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> is completely free. Drop me a<br />

line via shakespearemag@outlook.com if you’d like to advertise, make a<br />

donation, or just say hello.<br />

Enjoy your magazine,<br />

Pat Reid, Founder & Editor<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 3

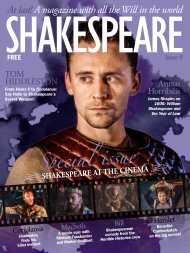

At last! A magazine with all the Will in the world<br />

SHAKESPEARE<br />

FREE<br />

Issue 7<br />

Antony Sher<br />

Why his new book is a<br />

love letter to Falstaff,<br />

Stratford and <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Great<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

actors<br />

Stanley Wells tells us<br />

what it takes to make<br />

a <strong>Shakespeare</strong> superstar<br />

From Russia<br />

with love<br />

David Tennant fans create<br />

their own edition of Richard II<br />

My<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Behind the scenes of the<br />

stellar documentary series<br />

Contents<br />

Plus!<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> in Turkey<br />

As You Like It<br />

The Essex Plot<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>an Opera<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Issue Seven<br />

June 2015<br />

Founder & Editor<br />

Pat Reid<br />

Art Editor<br />

Paul McIntyre<br />

Staff Writers<br />

Brooke Thomas (UK)<br />

Mary Finch (US)<br />

Contributors<br />

Francis RTM Boyle<br />

Julia Fedotova<br />

Rebecca Franks<br />

Anastasia Koroleva<br />

Cansu Kutlualp<br />

Maryna Reznikova<br />

Anna Ryzhova<br />

Chief Photographer<br />

Piper Williams<br />

Thank You<br />

Mrs Mary Reid<br />

Mr Peter Robinson<br />

Ms Laura Pachkowski<br />

Master Thomas Xavier Reid<br />

Web Design<br />

David Hammonds<br />

Contact Us<br />

shakespearemag@outlook.com<br />

Facebook<br />

facebook.com/<strong>Shakespeare</strong><strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Twitter<br />

@UK<strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Website<br />

www.shakespearemagazine.com<br />

The Fat Knight Rises 6<br />

Antony Sher tells us all about Year of the Fat Knight, his<br />

elegantly-written memoir of playing <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s Falstaff.<br />

“The actors are at hand...” 12<br />

Voice. Presence. Imagination… Stanley Wells tells us<br />

what it takes to become a Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Actor.<br />

<br />

4 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Contents <br />

The Remaking<br />

of Richard 16<br />

How a group of David Tennant<br />

fans crafted a truly original tribute<br />

to their <strong>Shakespeare</strong> hero.<br />

<br />

Small screen<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> 22<br />

Produced by Richard Denton<br />

and fronted by A-List actors,<br />

My <strong>Shakespeare</strong> is Top of the Docs.<br />

<br />

Lost in<br />

Arden 30<br />

British actress Zoe Waites heads<br />

to the USA to tackle one of<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s great roles: Rosalind.<br />

<br />

“Sweet airs, that<br />

give delight...” 36<br />

This pocket guide to <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

Greatest Opera Hits will surely<br />

be music to your ears…<br />

<br />

Eastern<br />

promise 38<br />

What has <strong>Shakespeare</strong> done to<br />

Turkey? (And what has Turkey<br />

done to <strong>Shakespeare</strong>?)<br />

<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

and sedition 42<br />

Unravelling the tangled web<br />

that links <strong>Shakespeare</strong> to the<br />

ill-fated Essex Plot of 1601.<br />

<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 5

Anthony Sher<br />

6 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Anthony Sher <br />

<br />

Left: Antony Sher<br />

as Falstaff. Right:<br />

<br />

In one of the landmark UK<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> productions<br />

of recent years, Gregory<br />

Doran directed his partner<br />

Sir Antony Sher as Falstaff<br />

in the RSC’s Henry IV Parts<br />

1 and 2. The actor’s diaries<br />

and drawings have now been<br />

published as Year of the Fat<br />

Knight, a revealing and highly<br />

entertaining account of an<br />

epic theatrical adventure.<br />

Interview by Pat Reid<br />

Illustrations by Sir Antony Sher<br />

The Fat<br />

Knight Rises<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 7

Anthony Sher<br />

Reading Year of the Fat Knight,<br />

what really comes across is<br />

the scale of the challenge. It’s<br />

practically the last page before you<br />

allow yourself to say ‘I’ve done it.<br />

Falstaff is mine’.<br />

“Falstaff was simply not a part I’d ever dreamed<br />

of playing. It just wasn’t on the radar, so I had<br />

an enormous mental challenge to start off, to<br />

decide whether I should try for it. And once I<br />

had, at every stage I was still dealing with the<br />

challenge: was I succeeding or wasn’t I? I think<br />

long before the last page I knew it was okay, I<br />

knew I was doing it and it was going to work,<br />

but it certainly took a very long time.”<br />

I’m taken aback by the sheer<br />

amount of preparation you did<br />

– academic research, historical,<br />

physical, looking at alcoholism –<br />

before we even get to rehearsals.<br />

And you’re drawing and sketching<br />

out your thoughts all the time<br />

as well as writing about it. Is this<br />

normal when you approach a<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> role?<br />

“There are certain parts where really all you<br />

need to do is bring your heart and soul to it.<br />

Research isn’t really going to make a lot of<br />

difference. For example, the part I’m playing<br />

at the moment, Willy Loman in Death of a<br />

Salesmen. I suppose I could have done a lot<br />

of research into being a travelling salesman in<br />

the ’40s in America. But it wouldn’t really have<br />

affected the playing of the role because it’s all<br />

about the man’s humanity, and you just have<br />

to bring your own humanity to that.<br />

But certain parts – and Falstaff was certainly<br />

one – need an awful lot of extra work.”<br />

“The plays are a love letter<br />

to an earlier England. Not<br />

Henry IV’s England, but<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s England”<br />

Mistress Quickly<br />

(Paola Dionisotti)<br />

and Falstaff<br />

(Antony Sher).<br />

I was intrigued by some of the<br />

Falstaffs that didn’t make it to<br />

the stage. This idea of playing<br />

him as a Vietnam veteran... Is<br />

there a moment when you decide<br />

something is absolutely wrong and<br />

you’re not going to proceed with it?<br />

“Good ideas and bad ideas are sometimes quite<br />

close together and it’s difficult to tell them<br />

apart. The classic example of that for me was<br />

when I played Richard III back in 1984 for the<br />

RSC, and there was this idea to play him on<br />

crutches. It was really quite difficult to work<br />

out whether that was a very good or a very<br />

bad idea. And the experimentation continued<br />

through rehearsals, in consultation with the<br />

director and the designer about whether these<br />

crutches were going to work. I think that’s a<br />

healthy part of the creative process, that you<br />

can discuss or try out certain things and say<br />

8 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Anthony Sher <br />

‘No, that isn’t going to work’ or ‘Yes, this is a<br />

bit dangerous, a bit risky, but it could work, so<br />

let’s keep with it.<br />

“The Falstaff as a Vietnam vet was from<br />

that period when Greg and I were considering<br />

whether one could do a modern dress<br />

production of the Henrys. And we’ve come to<br />

the conclusion that you can’t, or that we can’t.<br />

The plays are like a love letter to an earlier<br />

England. As Greg points out, it’s not Henry<br />

IV’s England, it’s Elizabethan England, it’s<br />

when <strong>Shakespeare</strong> was writing, and that’s what<br />

we ended up embracing and doing.”<br />

Difficult to talk about Falstaff<br />

without mentioning the F-word:<br />

fat. Having to wear a body suit<br />

Antony Sher’s<br />

Falstaff in full<br />

<br />

and having to get into that mind<br />

space was one of the challenges,<br />

especially with back pain as well.<br />

“Almost all Falstaffs wear a fat suit. Even Orson<br />

Welles, who was a very large man. In his film<br />

about Falstaff, Chimes at Midnight, I believe<br />

even he wore padding. Maybe this was a kind<br />

of vanity on his part that he wasn’t fat enough.<br />

But it’s certainly pretty regular for Falstaffs to<br />

have to wear what I prefer to call a body suit.<br />

I suppose it depends how they’re made. They<br />

could be made very very lightweight so that<br />

they wouldn’t be that burdensome, but in<br />

discussions with the designer, Stephen Brimson<br />

Lewis, he pointed out that if the fat suit was<br />

to work well it did need to be weighted in<br />

different sections so that it moved more like<br />

our bodies do, and so that did create a weight<br />

for it. And then of course Falstaff has to wear<br />

armour in the Shrewsbury battle sequences, so<br />

the weight was increased. And it was just an<br />

ongoing thing for me. After consulting with<br />

an orthopaedic specialist about my back we<br />

did lessen the weight of the fat suit but it was<br />

still weighted to some extent and it leads to<br />

a big discomfort factor in the performance. I<br />

sweated a great deal in every performance, just<br />

because you’re carrying this weight round with<br />

you, and you get very tired, you really have to<br />

sit down between scenes. There was always a<br />

special chair on either side of the stage which<br />

was mine.”<br />

And to complicate matters you<br />

then started to lose weight...<br />

“One of the great ironies is I had inadvertently<br />

discovered something called the Falstaff diet.<br />

If you wear a fat suit – and there’s the added<br />

pressure of course of playing this huge and<br />

famous part – you start to lose weight rapidly.<br />

But during about a year of playing it I stopped<br />

losing weight and I was quite surprised by how<br />

the body just adjusted to this new situation it<br />

was in.”<br />

The book’s very funny. The tale of<br />

breaking wind on a child minder<br />

made me laugh so hard I thought I<br />

was going to rupture something.<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 9

Anthony Sher<br />

“Theatre is hard and one can get very serious<br />

about it, and yet in reality there’s also a lot of<br />

laughter in rehearsals and backstage all the<br />

time and it’s important to catch that.”<br />

You seem intensely interested in<br />

everyone else in the production.<br />

You’re always doing sketches of<br />

them, in pictures and also in words.<br />

The descriptions of the activity,<br />

the production process and the<br />

armies of personnel are very vivid.<br />

“It’s important that readers understand the<br />

amount of people that go into a production.<br />

Audiences only ever see the people who<br />

appear on stage, the actors, but there is a vast<br />

amount of people behind the scenes. From<br />

stage management and stage crew to people in<br />

offices. It’s a huge organisation, the RSC, with<br />

people working on the production, promoting<br />

it, selling tickets. It’s a massive operation.”<br />

Falstaff jests with<br />

princely partnerin-crime<br />

Hal<br />

(Alex Hassell).<br />

From Falstaff to Willy Loman…<br />

Do you kind of wipe yourself clean<br />

between roles, or do you carry<br />

some of Falstaff over with you?<br />

“No, there’s no part that overlaps with another<br />

part, I’ve never known that to happen. A play<br />

or a part comes to an end and that’s it, it’s put<br />

away. Although in this case we are reviving<br />

the Henrys later this year, so not entirely put<br />

away, but normally it is. Now, as it happens,<br />

Falstaff and Willy Loman have something in<br />

common which is that they’re both fantasists.<br />

Some of the time they both live in their minds,<br />

in a fantasy world. But even that aspect is very<br />

different in the two plays.<br />

“Interestingly Alex Hassell who played Hal<br />

in the Henrys, is playing my son Biff in Death<br />

of a Salesman, and Willy and Biff have a very<br />

intense relationship. But it’s much closer to<br />

Hal’s relationship with his real father, the King,<br />

Henry IV than it is to his surrogate father<br />

Falstaff.”<br />

You mentioned that the Henrys<br />

are a love letter to <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

England. Your book reads like a<br />

love letter to Greg, to Stratford,<br />

and also to <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

himself. You never lose sight of<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> all the way through it.<br />

“I do feel an enormous affection, love for the<br />

Royal <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Company. It’s where I’ve<br />

spent most of my career, it’s been the most<br />

wonderfully rich experience. I’ve been so lucky<br />

to have been playing all these great <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

parts – and other classical parts, because the<br />

RSC does Jacobean playwrights as well. And<br />

the way things work, my partner Greg actually<br />

ended up becoming the Artistic Director of<br />

the company. It’s a beautiful completion of the<br />

circle. The company I love is now run by the<br />

person that I love.”<br />

I have to ask you about Henry<br />

IV Part 2. It must have been like<br />

climbing Mount Everest to find<br />

there’s another mountain that<br />

you’ve got to climb next. And<br />

Part 2 is a famously difficult play.<br />

10 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Anthony Sher <br />

“It is a different and much more difficult play<br />

and it took much harder work to make it<br />

work. I think in the end we did make it work<br />

and I feel proud of how we fought through<br />

that problem and, I think, solved it. But I<br />

think the times when Part 2 really works at<br />

its best is when we played the double days,<br />

we played Part 1 and Part 2 and you were<br />

aware that the same audience would stay for<br />

the whole marathon. When you go the whole<br />

distance with the two plays, when you get the<br />

whole story told, Part 2 really comes into its<br />

own. The souring of things that goes on in<br />

Part 2 becomes a much sadder, much more<br />

melancholy play.<br />

“And of course the journey that Hal and<br />

Falstaff go on through the two plays is a<br />

remarkable thing, that they start Part 1 as the<br />

absolute best of buddies and they end Part<br />

2 with Hal actually banishing Falstaff. It’s<br />

an extraordinary and wonderful and painful<br />

journey to go on, both for the actors and for<br />

the audience.”<br />

Clearly a very powerful bond<br />

developed with Alex Hassell<br />

when you were doing the Henrys.<br />

“There are certain relationships in certain<br />

plays where you really strike lucky. At the<br />

moment in Death of a Salesman it’s Harriet<br />

Walter who I’d already had a fantastically<br />

good time with when we played Macbeth.<br />

You just get that knowing one another so well<br />

in the way that husbands and wives do. The<br />

Falstaff and Hal relationship is another one of<br />

those relationships where if you really have a<br />

chemistry with the other actor you sort of get<br />

things for free, as it were, that the audience can<br />

sense and feel even if they can’t fully explain.<br />

There’s something happening on stage between<br />

the two actors that is particularly rich.<br />

“It was a great discovery one day in<br />

rehearsals when Alex and I discovered that in<br />

the sections where the two characters insult<br />

one another that it’s a kind of game and they<br />

enjoy it, and the characters would make one<br />

another laugh by being as insulting as possible.<br />

And that’s something you can only discover<br />

with an actor you’re really cooking with.”<br />

“Falstaff and Willy Loman<br />

have something in common<br />

in that they’re both fantasists.<br />

But they’re very different”<br />

You are one of very few living<br />

actors included in the new Stanley<br />

Wells book Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Actors – congratulations!<br />

“Oh, thank you, I’ll look forward to looking<br />

at that, because Stanley Wells has been a great<br />

influence here at the RSC, on the board and as<br />

an advisor. To have one of the world’s leading<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> scholars living locally here in<br />

Stratford and being so available to the RSC has<br />

been a very rich part of our history.”<br />

Have you thought about what will<br />

be your next <strong>Shakespeare</strong> role?<br />

“We have planned to do King Lear next year<br />

with Greg directing, here at Stratford. Beyond<br />

that, I don’t think there’s any left that I can<br />

play. I greatly regret that I never did Hamlet. It<br />

was purely my own fault. I grew up believing<br />

Hamlet had to be a tall, blonde, handsome<br />

character like in Olivier’s film and I sort of<br />

scuppered myself by sticking to that idea. And<br />

then of course other actors like Simon Russell<br />

Beale have proved that it doesn’t matter what<br />

Hamlet looks like, he can be anything. So I’m<br />

sorry I was so stupid about that.”<br />

The blood, sweat and tears of the<br />

Henrys… Has it all been worth it?<br />

“Absolutely yes. It could so easily have not been<br />

me, so I’m just enormously grateful. I would<br />

not have missed this experience for the world.”<br />

<br />

Year of the Fat Knight is available<br />

from Nick Hern Books priced £16.99<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 11

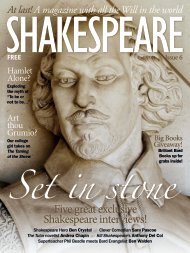

Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Actors<br />

“The<br />

actors<br />

are<br />

at hand…”<br />

Covering four centuries of thespian excellence from Richard<br />

Burbage to Kenneth Branagh, Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Actors is the<br />

latest book by pre-eminent <strong>Shakespeare</strong> scholar Stanley Wells.<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> visited the author in Stratford-upon-Avon<br />

<br />

Interview by Pat Reid<br />

The book had its origins in your<br />

writing for The Stage. Is there<br />

much of yourself in there?<br />

“It draws a lot on personal memory – I’ve been<br />

going to see <strong>Shakespeare</strong> for well over 60 years<br />

and I’ve seen some of the great <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

actors myself. The earliest one in the book<br />

chronologically that I saw is Edith Evans.<br />

Donald Wolfit I saw. And of course Gielgud,<br />

Olivier, Ralph Richardson, Peggy Ashcroft,<br />

right through to all the moderns – Ken<br />

Branagh and Simon Russell Beale.”<br />

What kind of source material did<br />

you use for the book?<br />

“I’ve drawn heavily on actors’ biographies –<br />

which are very patchy, actually. There are some<br />

very good ones, like Alan Strachan’s of Michael<br />

Redgrave, for example, and Jonathan Croall<br />

has done good ones of Gielgud and Sybil<br />

Thorndike. So I’ve drawn on those especially<br />

for the earlier actors, like Helen Faucit, for<br />

example, or Ira Aldridge or Edmund Kean,<br />

some of the really great figures of the past.<br />

“But also I’ve been able to draw on the<br />

resources here at the <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Centre<br />

in Stratford-upon-Avon. The <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Birthplace Trust has cuttings books of reviews<br />

which go back a long way, so for the actors<br />

who’ve appeared at Stratford I’ve used those.<br />

There’s a lot of Michael Billington in the book,<br />

for example, and the earlier JC Trewin, who<br />

wrote for the Birmingham Evening Post, was a<br />

very good <strong>Shakespeare</strong>an.”<br />

12 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Actors <br />

<br />

Above: Author and<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> authority<br />

Stanley Wells.<br />

Left: Kenneth Branagh’s is<br />

<br />

Were there any actors who went<br />

up or down in your estimation?<br />

“Yes, some people went out altogether, I’m<br />

afraid. I’ll tell you one, because he’s not a living<br />

actor… The American Edwin Forrest, I did<br />

some work on, I thought hard about him. But<br />

after reading more I began to feel he was just an<br />

old barnstormer and that he didn’t really deserve<br />

to be counted along with Edwin Booth who<br />

was his contemporary, who was a much more<br />

seriously good actor.<br />

“Charles Laughton was a bit of a dicey one,<br />

actually. He wasn’t a good verse speaker and one<br />

review of his early season at the Old Vic said<br />

‘Mr Laughton would be a great actor if he could<br />

keep his mouth shut’, which I thought was the<br />

ultimate insult. But he did an Angelo which was<br />

obviously very fine, he did a Macbeth which I<br />

think was probably patchy but great. I saw him<br />

here in Stratford when he did Lear not very<br />

well. But he did a very good performance as<br />

Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. So<br />

he got in, in the end.”<br />

Is there an actor inside you?<br />

Is that a different path you<br />

could have taken?<br />

“All teachers are failed actors, I think, ha ha.<br />

No, I haven’t got the temperament to act.<br />

I hope I have an actor somewhere within my<br />

head because in writing about <strong>Shakespeare</strong> –<br />

and especially editing <strong>Shakespeare</strong> – one does<br />

need to be very conscious of the actorliness<br />

of the texts, of the fact that <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 13

Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Actors<br />

Above: The “technically<br />

perfect” Judi Dench.<br />

Right: Ian McKellen is<br />

“a questing actor with<br />

a strong improvisatory<br />

streak”.<br />

himself was an actor. My first entry is on ‘Was<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> the first great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> actor?’<br />

And the answer is no, but I thought it was a<br />

question worth asking.”<br />

But you did tread the boards<br />

at the Globe last year…<br />

“That was just a bit of fun. Patrick<br />

Spottiswoode, Director of Education at the<br />

Globe, asked me to read the part of Old<br />

Knowell in Ben Jonson’s Every Man in His<br />

Humour in their series Read Not Dead, where<br />

you don’t memorise the role, you read it. And<br />

I agreed to do it. It was rather more arduous<br />

than I had expected it to be because it was a<br />

whole-day event. And also I was a bit surprised<br />

when I got there and looked around because<br />

some of these were rather eminent actors.<br />

However I think I held my own…”<br />

Is there one figure from the whole<br />

four centuries who you think is the<br />

most pivotal? Perhaps one who is<br />

not obvious…<br />

“The greatest? I think the obvious ones<br />

probably are the greatest. Edmund Kean I’d<br />

love to have seen. There was that famous<br />

remark about him by Coleridge: ‘seeing him<br />

act <strong>Shakespeare</strong> was like reading <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

by flashes of lightning’. It’s not entirely a<br />

compliment, it implies that there wasn’t a<br />

degree of continuity within the characters that<br />

he played. But I’m sure he was a terrifically<br />

exciting actor. The only one I can compare<br />

14 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Actors <br />

him with in that way is Laurence Olivier,<br />

whom I did see. And I would say that the<br />

greatest performance I’ve seen myself is<br />

Laurence Olivier as Coriolanus here in 1959,<br />

when Edith Evans was also fine as Volumnia.<br />

She was a little bit old for the role but she gave<br />

a great performance too.”<br />

Tell us about some of your<br />

personal favourites.<br />

“I’ve been lucky to see and indeed to know<br />

some of the great actors. Donald Sinden was<br />

a friend. One who there’s a rather sad story<br />

about is Richard Pasco who died not long ago.<br />

He lived not far from here, I talked to him a<br />

lot when he was here, and I did talks with him<br />

and Ian Richardson, especially when they were<br />

playing Richard II, when they were alternating<br />

the roles of Richard and Bolingbroke in John<br />

Barton’s great production here.<br />

“I knew that Dickie had Alzheimer’s and I<br />

happened to see his wife Barbara Leigh-Hunt,<br />

herself a very fine <strong>Shakespeare</strong> performer, and<br />

I said ‘I’ve just written an essay about him’. She<br />

said could she read it, so I sent her the book.<br />

After he died she told me that she read the<br />

essay to him twice. She said that it moved him<br />

to tears. He wasn’t able to remember a word of<br />

it an hour afterwards, but I was so pleased that<br />

I had both written it and sent it to him.”<br />

You mentioned that some actors<br />

would be great if they kept their<br />

mouths shut. How does it divide<br />

between the physicality, the voice<br />

and other things?<br />

“What are the qualities that go towards<br />

making a great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> actor? They<br />

include presence, the ability to stand still, the<br />

ability to be silent, to listen silently, the ability<br />

to speak eloquently, movement, gesture are<br />

all important. But ultimately there’s a quality<br />

which is indefinable and which sometimes<br />

defies the rules. Henry Irving was clearly a<br />

very great actor, but he had a terrible voice<br />

and his diction was very eccentric. There are<br />

a lot of rather funny remarks that I quote<br />

about Irving’s diction, from Henry James for<br />

example. Even Ellen Terry, his partner – in<br />

acting and in real life too – in her wonderful<br />

“Coleridge said that seeing<br />

Kean act <strong>Shakespeare</strong> was<br />

like reading <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

by flashes of lightning”<br />

book of memoirs has a transcript of an<br />

American journalist’s attempt to transcribe<br />

Irving’s very eccentric pronunciation.<br />

“So ultimately there’s a quality which you<br />

can’t define, a quality of genius, the quality<br />

of responding to the language. In our own<br />

time Judi Dench has it, for example. She is<br />

somebody who is more technically perfect and<br />

adept than some of the others. There’s also<br />

this quality of imagination, the ability to think<br />

yourself into a role.<br />

“And yet there’s a lovely quotation from<br />

Donald Sinden about how when he was<br />

playing Malvolio he had both to be inhabiting<br />

the character but at the same time to be<br />

standing aside from the character. He said that<br />

if at any point he actually became Malvolio he<br />

lost control over the audience. And I think that<br />

is a good definition of the way that an actor<br />

has to be both in and out of the part at the<br />

same time.”<br />

It must have been hard to make<br />

your final selection…<br />

“Because of the difficulty of choosing, among<br />

living actors especially, I’ve dedicated the book<br />

‘to all the great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> actors who are not<br />

in this book’, which I hope is tactful…”<br />

<br />

Great <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Actors by Stanley Wells<br />

is available from Oxford University Press,<br />

priced £16.99<br />

William <strong>Shakespeare</strong>: A Very Short<br />

Introduction by Stanley Wells is also available<br />

from Oxford University Press, priced £7.99<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 15

Richard II<br />

For some <strong>Shakespeare</strong> fans, getting a poster or an autograph is an adequate<br />

souvenir of their favourite stage production. This group of David Tennant<br />

fans in Moscow, however, were slightly more ambitious. They decided to<br />

create their own bespoke hardcover edition of Richard II….<br />

Words by Anastasia Koroleva. Translated into English by Maryna Reznikova and Julia Fedotova.<br />

Illustrations by Anna Ryzhova<br />

The<br />

Remaking<br />

of<br />

Richard<br />

16 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Richard II <br />

David Tennant’s<br />

Richard II and his<br />

hollow crown.<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 17

Richard II<br />

“As luck would have it, a passer-by took a photo<br />

at the moment I was passing the book to David”<br />

Two years ago, Gregory Doran, the Artistic<br />

Director of the Royal <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Company,<br />

put on <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s Richard II in Stratfordupon-Avon<br />

with David Tennant in the title<br />

role. In January 2014 the filmed performance<br />

was shown in Russian cinemas.<br />

This broadened the audience of the<br />

production, as it became available to thousands<br />

of people, and then tens of thousands more<br />

when the DVD was released in May. This<br />

made it possible to start our project. While<br />

many of us actually travelled to the UK from<br />

Russia especially to see the play, without the<br />

video our book project would not have gained<br />

such support.<br />

It all started with a post on the Russian<br />

social network VKontakte on 18 May 2014<br />

in which artist Anna Ryzhova published<br />

her drawings inspired by the production of<br />

Richard II.<br />

I posted a comment saying it would be<br />

great to publish <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s play with those<br />

drawings and the translated text edited by<br />

us. My idea was accepted with enthusiasm<br />

The book’s<br />

illustrations are<br />

rich in symbolism.<br />

and it immediately set the wheels in motion.<br />

We opened a bank account specifically for<br />

the project, calculated the potential expenses<br />

and started to raise money for layout and<br />

printing. From the very start the project was<br />

crowdfunded and purely non-profit.<br />

We had to take English and Russian<br />

texts and edit them. We chose not simply to<br />

publish a parallel version of the play in the<br />

two languages, but also to mark the parts<br />

which had been omitted from the original<br />

play by Gregory Doran in his production.<br />

This was complicated by the fact that the text<br />

had to be literally ‘parallel’ – that is, the same<br />

lines had to be placed on the same level. And<br />

since Russian translation of the line is almost<br />

always longer, this was not an easy task. It was<br />

necessary to watch the recording very carefully<br />

(and rewatch and rewatch and rewatch) and<br />

meticulously mark them in the text.<br />

The Russian translation of Richard II by<br />

A. Kurosheva was the most precise available,<br />

but for some lines we needed more. We had<br />

a lot to rack our brains about, and sometimes<br />

18 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Richard II <br />

The team set<br />

out to make an<br />

artefact that was<br />

both beautiful<br />

and educational.<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 19

Richard II<br />

it took months to find a worthy translation<br />

equivalent.<br />

The book also contains commentaries and<br />

notes. We gathered them from existing Russian<br />

publications and wrote a couple on our own.<br />

A remarkable foreword was written by<br />

Natalia Fomintseva, who did tremendous work<br />

researching literary sources. Her sophisticated<br />

text intertwines a review of Gregory Doran’s<br />

production with a concise version of Richard<br />

II’s real life. We translated the foreword into<br />

English (our thanks to Natalia Koroeva and<br />

Maryna Reznikova). The book doesn’t include<br />

the foreword in English, but we sent it to<br />

everybody interested, and also passed it on to<br />

Gregory Doran, the RSC and David Tennant.<br />

Artist Anna Ryzhova worked on the<br />

drawings, and this also turned out to be<br />

a tricky task. Since from the very start we<br />

planned to publish not only a digital edition,<br />

but also a hardcover book, we had to figure<br />

out how the illustrations would look on paper<br />

– because they were originally made on music<br />

paper. We went to a printing house to see<br />

for ourselves, and eventually the music paper<br />

version had to be rejected. As a result, all the<br />

drawings, even those that had been sketched,<br />

were made from scratch.<br />

We chose to print the half-title pages (a<br />

half-title is a page which opens a chapter or<br />

Holding the mirror<br />

up to David Tennant’s<br />

Richard II.<br />

part of a book), end leaves and cover in colour.<br />

The other drawings are black and white with<br />

one or two colours added.<br />

Although we decided not to go with a<br />

universally recognised crowdfunder platform<br />

like Kickstarter, we were able to raise the<br />

money without incident. Thank you to all the<br />

members who have trusted us. We remind you<br />

once again that the project was crowdfunded,<br />

the organisers have not earned a penny, and all<br />

the money raised went towards printing and<br />

postage costs.<br />

The book happily reached many<br />

different countries and we received dozens of<br />

enthusiastic comments.<br />

“The books arrived already!!! I did not expect<br />

them to be here SO fast! They look wonderful<br />

and I am so impressed with your work.<br />

I am a typesetter and my family publishes<br />

magazines, so my daily life is about printing<br />

and preparing stuff to be printed. Therefore<br />

I know for real how good your book is – not<br />

just from a fan-view. I thank you again very<br />

much for allowing me to get these two copies.<br />

It means a lot to me to have them.”<br />

– Marion, Germany<br />

“I can’t believe when I saw the book at<br />

first because it’s much better than what I<br />

20 SHAKESPEARE magazine

“A remarkable foreword to the book was written<br />

by Natalia Fomintseva who did tremendous<br />

work researching literary sources”<br />

Richard II <br />

expected! Really awesome, magnificent and<br />

I’m gonna love it! I can see the efforts of you<br />

and your team put into in everywhere. Such a<br />

masterpiece.” – Yaewon, Korea<br />

“The beautiful book arrived in Colorado on<br />

11 February 2015. I can’t wait to sit down<br />

and really go through it!!! Great job to all<br />

involved!!!” – Sue, Colorado, USA<br />

And yet Gregory Doran and David<br />

Tennant’s own words became the best<br />

recognition for us. On 12 January 2015<br />

David was supposed to host a live broadcast<br />

on Absolute Radio. I went to London, having<br />

From Russia with<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> Love…<br />

taken three copies of the book – for Gregory<br />

Doran, RSC’s archives and, naturally, Mr<br />

Tennant himself. I was going to pass David his<br />

copy after the show, while the other two were<br />

to be left at the RSC’s London office.<br />

David kindly spared a minute after the live<br />

broadcast to sign autographs, and that was<br />

when he was handed his copy of the book.<br />

He stared at the book cover in roundeyed<br />

wonder, literally, and a sincere “Oh my<br />

goodness!” slipped out. “From Russia?” he<br />

asked again in amazement, as if he found it<br />

hard to believe it had been made in Russia.<br />

“Is it for ME?” David asked. “Or do you want<br />

me to sign it?” As luck would have it, a passerby<br />

took a photo at the exact moment I was<br />

passing the book to David.<br />

It was not the end of the story. On 15<br />

February the What’s On Stage Awards was<br />

held in London, and I attended. David<br />

Tennant had been nominated for Best Actor<br />

for his part in Richard II, and Gregory Doran<br />

for Best Direction. As you’ll know, David won.<br />

And I was exceptionally lucky to have a chat<br />

with Gregory and David before the start of the<br />

show. Gregory called the book “extraordinary”,<br />

while David’s epithet was “amazing”. This is<br />

the best reward we could hope to receive.<br />

FAST FACTS<br />

Five months of work in our<br />

spare time, on weekends, on<br />

vacation, and often at night.<br />

More than 30 illustrations.<br />

220 pages of Russian and<br />

English text.<br />

Raised 193,000 RUB (about<br />

$4,000) to print 130 copies.<br />

Over 125 people from Russia,<br />

Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan,<br />

Germany, USA, Great Britain<br />

and Korea participated.<br />

The copies, fresh from print,<br />

weighed 86 kilos.<br />

The books were sent to<br />

owners in 50 cities around<br />

the world.<br />

Director Gregory Doran and<br />

actor David Tennant each<br />

received a copy as well.<br />

<br />

Anastasia and her friends are now working on a<br />

new edition of Hamlet (based on Gregory Doran’s<br />

2008 RSC production starring David Tennant).<br />

You can enjoy the digital version of their Richard<br />

II book here: http://issuu.com/anastasiako/<br />

docs/richard_ii._the_book<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 21

My <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Veteran documentary maker<br />

Richard Denton wanted<br />

to make a series that, like<br />

himelf, was evangelical<br />

about the Bard. The result<br />

was My <strong>Shakespeare</strong> (titled<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> Uncovered in<br />

the USA). Smart, accessible,<br />

and fronted by A-List actors,<br />

it’s a TV triumph…<br />

Interview by Pat Reid<br />

22 SHAKESPEARE magazine

“I remember telling<br />

my schoolteacher<br />

‘I don’t buy that<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s any<br />

better than anybody<br />

else, it’s just you lot<br />

saying he is’”<br />

Above:<br />

Documentary<br />

maker and Bard<br />

Evangelist<br />

Richard Denton.<br />

Left: Morgan<br />

Freeman<br />

presented the<br />

episode on The<br />

Taming of the<br />

Shrew.<br />

How did this project begin for you?<br />

“It began about five years ago when I was<br />

listening to a programme about King Lear on<br />

the radio, and I just went ‘God, we should do<br />

documentaries about every single play. Why<br />

hasn’t anybody ever done that? You know the<br />

old Prefaces to <strong>Shakespeare</strong> books by Granville<br />

Barker? Why not do it on television?’ So I<br />

started putting that together as a project,<br />

originally with the intention of covering<br />

all 37, but realising that would probably<br />

be impossible. I came up with a project<br />

to do about 20, and I went initially to the<br />

Americans, to PBS, WNET in America,<br />

and they said ‘Yeah, you got me at Prefaces’.<br />

So that was easy, they were game. And then it<br />

took me two-and-a-half years to persuade the<br />

BBC to do it.” [laughs]<br />

“That’s been the weird part of the journey,<br />

I suppose. The huge enthusiasm of the<br />

transatlantic and world audience for these<br />

My <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <br />

<br />

films, and the relative indifference to them in<br />

the UK. It’s very, very odd. When the BBC<br />

took the first series they then rather reluctantly<br />

put them out at obscure times. I remember<br />

one of the reviewers saying ‘What custard<br />

brain at the BBC decided to transmit this<br />

gem at ten past eleven on a Tuesday?’ So it<br />

was something of a nightmare. And then they<br />

didn’t want to have another series, they only<br />

wanted the first six. So then Sky Arts took on<br />

the second six, but obviously there’s a limit to<br />

how far their budgets go…<br />

“And to be honest with you, I don’t think<br />

it’s got a particularly large audience in the UK.<br />

It’s got a very nice audience in America and –<br />

I will say this – the people who did watch it<br />

in the UK were hugely enthusiastic about it.<br />

It’s separated out a group of people and given<br />

them something they’ve absolutely loved,<br />

but it’s not as large a group as we had hoped<br />

originally.<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 23

My <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

How would you describe the<br />

programme’s format?<br />

“Basically the idea was we would take a play,<br />

we would find a presenter. It wasn’t necessarily<br />

going to be an actor but the easiest and most<br />

obvious thing was to take either an actor or<br />

director – who either knew it or wanted to<br />

know it, had an enthusiasm for it – and then<br />

investigate… Why did <strong>Shakespeare</strong> write it?<br />

Where did he get it from, since very few of his<br />

stories are original? How was it when it was<br />

first shown? What’s happened to it since?”<br />

What was behind your personal<br />

enthusiasm for <strong>Shakespeare</strong>?<br />

“I studied English and American Literature<br />

when I was at university, I went to Stratford<br />

when I was at school. I remember telling my<br />

schoolteacher ‘I don’t buy that <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

any better than anybody else, it’s just you lot<br />

saying he is’. Then he made me read Beaumont<br />

and Fletcher, and I went ‘Oh yeah, you’re<br />

Derek Jacobi<br />

presented the<br />

episode on<br />

Richard II.<br />

right. He’s much better, isn’t he? Sorry! Beg<br />

your pardon…’<br />

“But as I’ve got older I suppose my passion<br />

has grown for it. I feel almost evangelical<br />

about it. It’s the most extraordinary repository<br />

of wisdom about humanity ever written.<br />

It’s vastly entertaining. I challenge you to<br />

go to the Globe and see a <strong>Shakespeare</strong> play<br />

– even a tragedy – and not just be hugely<br />

entertained by it. It’s much less difficult than it<br />

seems – although initially it seems incredibly<br />

difficult, and I do understand that. And I feel<br />

passionately that everybody should know this<br />

stuff. And the world would be a better place if<br />

we all did.”<br />

You’ve basically just summed<br />

up the manifesto of <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

<strong>Magazine</strong>.<br />

“Absolutely!”<br />

The format you’ve come up with<br />

works like a dream, especially<br />

having these great talents who are<br />

also household names fronting the<br />

programme. Can you tell me about<br />

some of the personalities involved?<br />

“Oddly enough, it’s proved much more<br />

difficult to get them than you would think.<br />

And the reason, I think, is that a lot of<br />

actors feel terribly self-conscious about being<br />

themselves, and they don’t want to be accused<br />

of being luvvies. I constantly had to reassure<br />

them ‘I’m not going to have you [adopts<br />

mournful thespian voice] emoting about how<br />

moving and how difficult it is. We’re going to<br />

have fun. We’re going to take it seriously, but<br />

we are going to have fun’.<br />

“So I think a lot of actors felt terribly<br />

uneasy about it, and there were quite a few<br />

who turned it down because they just didn’t<br />

feel comfortable. And even the ones who did<br />

it had their moments of ‘Oh, I don’t feel I’m<br />

entitled to say any of this’. And yet they did in<br />

the end.”<br />

You had a tight-knit team…<br />

“There were only a few directors working on<br />

the show. One was my partner Nicola Stockley<br />

who did Macbeth, Othello, Hamlet and Lear –<br />

all the four big bastards.”<br />

24 SHAKESPEARE magazine

My <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <br />

Above: David Tennant<br />

chats about Hamlet<br />

with Jude Law.<br />

Below: Jeremy Irons<br />

tackled both Henry IV<br />

and Henry V.<br />

“David<br />

Tennant on<br />

Hamlet was<br />

a complete<br />

copybook<br />

example of<br />

how to do it.<br />

He had a lot of<br />

fun with it but<br />

he also took it<br />

seriously”<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 25

My <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

“The<br />

Above: David<br />

Harewood gave us<br />

his take on Othello.<br />

Below: Joseph<br />

Fiennes delved into<br />

Romeo and Juliet.<br />

appetite<br />

for <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

in America is<br />

unquenchable.<br />

And they love<br />

to celebrate<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>.<br />

We in England<br />

are really crap<br />

at celebrating<br />

things”<br />

26 SHAKESPEARE magazine

My <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <br />

<br />

Sorry, did you just refer to<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s four great<br />

tragedies as ‘the big bastards’?<br />

“The point is you have to take them seriously<br />

but you can’t get up yourself when you’re<br />

talking about them because you just put people<br />

off. That’s why I thought David Tennant on<br />

Hamlet was a complete copybook example of<br />

how to do it. He had a lot of fun with it but he<br />

also took it seriously.”<br />

It can’t have been easy finding all<br />

the A-listers to front the episodes.<br />

“It was tricky trying to get hold of the talent.<br />

Do you know the easiest one? Morgan<br />

Freeman. I rang his agent, his agent said ‘I’ll<br />

ask him’. Came back the next day, said ‘Yeah,<br />

he’ll do it’. That was it – no questions asked.<br />

[laughs] This is a man who normally doesn’t<br />

get out of bed for a couple of million, and he<br />

was doing it for literally peanuts.”<br />

Kim Cattrall<br />

celebrated<br />

her favourite<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> role:<br />

Cleopatra.<br />

That was a great episode as well…<br />

“It was fun. We didn’t have a lot of time<br />

with him but he invited us to his house and<br />

we filmed him in LA, and also he’s hugely<br />

enthusiastic about it.”<br />

The format also allows for<br />

interesting personal revelations,<br />

like the moment when Tracey<br />

Ullman told Morgan Freeman, ‘You<br />

don’t know this, but in England I’m<br />

seen as common. I don’t get asked<br />

to do <strong>Shakespeare</strong>…’<br />

“Yes, I think she touched on something.<br />

The appetite for <strong>Shakespeare</strong> in America is<br />

unquenchable. They absolutely love it. And<br />

they’re not embarrassed by it, they’re not<br />

ashamed by it. And they love to celebrate<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>. We in England are really crap<br />

at celebrating things. Especially if they’re our<br />

own. You know, in America they have a series<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 27

My <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Richard<br />

“The easiest one was<br />

Morgan Freeman.<br />

This is a man who<br />

normally doesn’t<br />

get out of bed for a<br />

couple of million…”<br />

called American Masters where they make a<br />

film about Leonard Bernstein or Philip Roth<br />

or whoever. But in England if I try to make<br />

‘<strong>Shakespeare</strong>: Isn’t He Just Wonderful?’ I get<br />

‘Oh. Um. Er. That’s a bit boring’. I don’t really<br />

understand it. Very odd.<br />

“When Nicola and I went to America for<br />

the launch of the first series – and indeed the<br />

second series – we felt quite giddy because<br />

people were coming up to us and just saying<br />

‘It’s so wonderful, thank you so much for<br />

making it’. Whereas most people we were<br />

putting the programmes to in England were<br />

like ‘It’s all right’. Very strange.”<br />

Well, as a <strong>Shakespeare</strong> fan I can<br />

tell you it’s a brilliant series.<br />

Speaking of ‘The Four Big<br />

Bastards’, I had to psych myself up<br />

to watch the Othello and King Lear<br />

episodes because I thought they<br />

were going to be really heavy. So I<br />

made myself watch them early on<br />

and discovered they were actually<br />

very entertaining episodes.<br />

“Aren’t they just? The wonderful King Lear<br />

with the happy ending done in Restoration<br />

comedy style. Christopher Plummer was just<br />

wonderful, he was a lovely man to work with.<br />

And David Harewood’s take on Othello was<br />

really interesting. That lovely meeting with<br />

him and Adrian Lester talking about people<br />

criticising the [19th century Ira Aldridge<br />

version of] Othello. Oh my goodness, that was<br />

quite something.”<br />

Denton<br />

(right) with<br />

Morgan Freeman:<br />

“We’re going to<br />

take it seriously,<br />

but we are going<br />

to have fun.”<br />

Two excellent actors and some<br />

very serious issues, but it was great<br />

that they found humour in it. That<br />

was an excellent way of dealing<br />

with the whole thing.<br />

“In a sense, what I hoped the series would do<br />

– and only time can tell, I suppose – is that<br />

for people who knew a bit of <strong>Shakespeare</strong> and<br />

liked <strong>Shakespeare</strong>, like yourself, they would be<br />

entertaining and they would provide a couple<br />

of new things that you might not know. But<br />

at the same time you may notice that the<br />

actual format involves going through the play<br />

absolutely chronologically in the story.<br />

“So if you’ve never read the play you’ll<br />

know what the story is by the time you get<br />

to the end of the film. But we won’t do it in<br />

such a way that it’s incredibly boring. It sort of<br />

emerges as you go along, so that if you’ve never<br />

seen the play you’ll end the film thinking ‘I’d<br />

quite like to see that’.<br />

“And if we’ve done those two things, we’ve<br />

cracked it.”<br />

<br />

28 SHAKESPEARE magazine

As You Like It<br />

Lost in<br />

Arden<br />

When director Michael Attenborough took on<br />

the <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Theatre Company’s recent<br />

production of As You Like It, he was adamant<br />

about two things: it didn’t need to be funny,<br />

but it did need an utterly brilliant Rosalind…<br />

Words: Mary Finch<br />

30 SHAKESPEARE magazine

As You Like It <br />

<br />

Melancholy Jaques<br />

(Derek Smith)<br />

interrupts the Duke<br />

(Timothy D. Stickney)<br />

and his merry men<br />

of the forest.<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 31

As You Like It<br />

“Were it not<br />

better... that I did<br />

suit me all points<br />

like a man?”<br />

Zoe Waites as<br />

Rosalind.<br />

rying for the final 15 minutes<br />

of a comedy hardly seems<br />

reasonable. But when it<br />

comes to <strong>Shakespeare</strong> and<br />

me, reason has no place. This<br />

happened last December, and<br />

the production in question<br />

was As You Like It by the<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> Theatre Company<br />

in Washington DC.<br />

Last season, the STC’s Henry IV Parts 1<br />

& 2 swept me away, and even though As<br />

You Like It couldn’t be a more different play,<br />

I felt the same emotional tightness in my<br />

chest as the curtain fell. Despite already<br />

loving this play – something about sassy<br />

androgynous female characters just really<br />

speaks to me – I was completely caught off<br />

guard by the production. But considering<br />

the story of how it came to be, that<br />

powerful result is hardly surprising.<br />

This As You Like It was the fruit of a<br />

partnership between STC Artistic Director<br />

Michael Kahn and Michael Attenborough,<br />

who is well known for his work as Associate<br />

Director of the Royal <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Company in Stratford-Upon-Avon and<br />

artistic Director of the Almeida Theatre in<br />

London’s Islington.<br />

When Kahn first invited Attenborough<br />

across the pond as a guest director, all<br />

parties were willing, but the schedules were<br />

not permitting. After patiently staying in<br />

touch for several years, the stars – and dates<br />

– aligned and plans were made.<br />

The only snag in the production was<br />

32 SHAKESPEARE magazine

As You Like It <br />

finding the perfect Rosalind. Discussing the<br />

search, Attenborough recalls: “I actually said<br />

at one point, ‘Michael, we shouldn’t do this<br />

play, if we don’t have a brilliant Rosalind’.”<br />

Luckily for audiences, they found one in<br />

Zoe Waites.<br />

The casting wasn’t exactly chance,<br />

though. Waites and Attenborough first<br />

worked together in 1998, when he cast her<br />

as the titular heroine in the RSC’s Romeo<br />

and Juliet. Even then, at 22, she displayed<br />

the emotional bravery that would manifest<br />

in Rosalind.<br />

“She is absolutely fearless, particularly,<br />

emotionally fearless,” says Attenborough.<br />

“The more you stretch her, the more she<br />

likes it.”<br />

Both Attenborough and Waites are<br />

originally from the UK, so this production<br />

had the additional challenge of bringing<br />

them to a city and a country far from home.<br />

“It was great fun, being in a rehearsal<br />

room with him outside of our comfort<br />

zone,” says Waites. “There was something<br />

“Now I am in<br />

Arden!” Rosalind,<br />

Celia (Adina Verson)<br />

and Touchstone<br />

(Andrew Weems)<br />

rough it in the forest.<br />

very liberating about it for both of us.”<br />

As I mentioned, this production had<br />

me weeping at the end. While it is not<br />

uncommon for <strong>Shakespeare</strong> to make me<br />

cry, generally that emotion occurs during<br />

tragedies, or merely manifests through a<br />

subtle mistiness in the eyes. The emotional<br />

punch of this comedy, however, came<br />

through the vulnerability of the characters.<br />

Before the main action of the play,<br />

Rosalind and Orlando (Andrew Veenstra)<br />

shared a moment of grief on stage – since,<br />

as described by Attenborough, they are<br />

“two people in the depths of despair”.<br />

The actors created this tragic<br />

vulnerability because their director freed<br />

them from the burden of comedy.<br />

“On day one,” Michael Attenborough<br />

explains, “I said to the company: ‘I hereby<br />

am giving you all absolute, unqualified<br />

permission not to be funny. I don’t want<br />

anyone straining to be funny’.”<br />

Speaking of characters straining for laughs,<br />

Attenborough couldn’t resist sharing an<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 33

As You Like It<br />

Two characters<br />

in search of four<br />

happy endings:<br />

Rosalind and Celia.<br />

“Zoe Waites is<br />

absolutely fearless. The<br />

more you stretch her,<br />

the more she likes it”<br />

Michael Attenborough<br />

34 SHAKESPEARE magazine

As You Like It <br />

anecdote. “A friend of mine – I think he’s<br />

quite well known in America as well, a guy<br />

named David Tennant – said to me once,<br />

‘Do you know what the loneliest place in<br />

the world is?’ And I said, ‘What’s that?’ He<br />

said, ‘Playing Touchstone, because he’s just<br />

not very funny’.”<br />

However, in this production Corin fully<br />

enjoys Touchstone’s courtly antics, and<br />

the shepherd’s simple, infectious laughter<br />

spread through the entire theatre. So there<br />

were still many moments of genuine ribbreaking<br />

humour, and the more serious bits<br />

in between only amplified the funny ones.<br />

In the end, all of the comedy and<br />

tragedy pulled together to tell the story<br />

of Rosalind, for she truly was the centre of<br />

this production. Interviewed separately,<br />

both Attenborough and Waites describe<br />

Rosalind as smart, witty, and terrified of<br />

being in love.<br />

“She’s a cerebral girl who is completely<br />

astonished and overwhelmed by these<br />

feelings of sexual attraction and desire, and<br />

this thing that feels like love,” says Waites.<br />

For all her intelligence, though, Waites’<br />

“Rosalind is completely<br />

astonished and overwhelmed<br />

by sexual attraction and<br />

desire, and this thing that<br />

feels like love”<br />

Zoe Waites<br />

Rosalind and Orlando<br />

(Andrew Veenstra).<br />

Our heroine puts his<br />

commitment – and<br />

her own – to the test.<br />

Rosalind never had everything figured<br />

out – far from it. She flew between joy and<br />

grief, love and suspicion, hope and doubt.<br />

As Waites saw it: “Rosalind’s just sort of<br />

improvising and taking advantage of the<br />

moment.”<br />

Attenborough sees this complexity<br />

as reminiscent of Hamlet, arguably the<br />

Bard’s greatest character: “Hamlet is split<br />

between action and inaction,” he says, “his<br />

conscience and his duty. Rosalind is almost<br />

more profound. She is split between her<br />

heart and her brain – or to be more vulgar,<br />

her groin and her brain.”<br />

For Attenborough, that duality and<br />

uncertainty is not only the central conflict<br />

for Rosalind, but also for <strong>Shakespeare</strong>.<br />

“<strong>Shakespeare</strong> is almost built –<br />

structured linguistically – on the idea<br />

of antithesis. You can almost look at<br />

any speech and it is structured around<br />

antithetical nouns, adjectives, ideas.”<br />

Despite all of the conflict and vulnerability<br />

that happens along the way, the characters<br />

do get happy endings, in the form of four<br />

simultaneous weddings, a dukedom restored,<br />

and families reunited. But for Waites it is not<br />

just the multiple happy endings that draw the<br />

audience in. “We are intrigued and excited<br />

watching these characters go to Arden,” she<br />

says, “and bumble around, finding themselves<br />

and falling in love. Because that is what we’re<br />

doing, or what we would like to be able to do.”<br />

<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 35

Opera<br />

“Sweet airs,<br />

that give<br />

delight...”<br />

It’s time for a spot of Desert Island Discs, as our esteemed Music<br />

Correspondent chooses the eight best bits from operas inspired by<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>. With selections from Verdi, Berlioz, Purcell, Britten<br />

and Bernstein, this is <strong>Shakespeare</strong> music with a real wow factor…<br />

Words: Rebecca Franks<br />

After hearing composer Ambroise<br />

Thomas’s Hamlet, Verdi is reported to<br />

have said: “Poor <strong>Shakespeare</strong>, how they<br />

have mistreated him.” It’s a comment<br />

that could apply to a good number of<br />

operas inspired by the Bard. Despite<br />

the eternal allure of <strong>Shakespeare</strong> for<br />

composers, only a handful of the 200<br />

plus works have gone on to become<br />

true classics. And working out why this<br />

should be is probably a whole other<br />

story in itself.<br />

But when it all comes together, the<br />

combination of <strong>Shakespeare</strong>an drama<br />

and character with the rich musical<br />

world of opera is utterly sublime.<br />

Here are eight of the truly great<br />

moments to listen to.<br />

Hector Berlioz<br />

‘Nuit paisible et sereine’<br />

From Béatrice et Bénédict (1863)<br />

Imagine it’s night. The moon is shining and there’s a<br />

gentle breeze. It’s peaceful, apart from the soothing<br />

sounds of insects and birds. It’s that moment of blissful<br />

stillness that Berlioz captures to perfection in ‘Nuit<br />

paisible et sereine’, a duo that comes at the end of<br />

the first act of his Much Ado About Nothing opera,<br />

Béatrice et Bénédict.<br />

Heró and her lady-in-waiting Ursule have been<br />

busy matchmaking but here all the high jinks pause.<br />

Their voices intertwine as they sing to ‘la lune, douce<br />

reine’ – ‘the moon, sweet queen’.<br />

Ralph Vaughan Williams<br />

‘Fantasia on Greensleeves’<br />

From Sir John in Love (1929)<br />

‘Let the sky rain potatoes, let it thunder to the tune<br />

of Greensleeves,’ said Falstaff in The Merry Wives of<br />

Windsor, the play that inspired Vaughan Williams’s<br />

Sir John in Love. And it’s the Fantasia on Greensleeves,<br />

adapted by Ralph Greaves from that very opera, that’s<br />

become one of the work’s best-known moments.<br />

Vaughan Williams’s setting of the already haunting<br />

Greensleeves, a ballad popular since the 16th century,<br />

is big on atmosphere: a flute and harp conjure up a<br />

pastoral English feel, before the strings wordlessly sing<br />

the melody, accompanied by a harp strumming as if it<br />

were a lute in the Tudor court.<br />

36 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Opera <br />

Charles Gounod<br />

‘Juliet’s Waltz’<br />

From Roméo et Juliette (1867)<br />

This is an intoxicatingly joyous whirlwind of a waltz.<br />

Juliet sings of her dreams of love and her zest for life in<br />

an aria that sparkles and dances. Sung just before her<br />

fateful meeting with Romeo, Juliet has declared she’s not<br />

interested in marriage. This moment is all about youthful<br />

hopes and innocent pleasures, yet when she sings that<br />

love might destroy happiness, there’s a hint of the tragedy<br />

to come. Even though it was a last-minute addition by<br />

Gounod, ‘Je veux vivre’ (I want to live) became one of<br />

the most popular parts of his opera.<br />

Giuseppe Verdi<br />

‘La luce langue’<br />

From Macbeth (1847)<br />

Just as Juliet’s Waltz finds no counterpart in <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

original play, the aria ‘La luce langue’ (the light is<br />

languishing) was of Verdi’s own creation. It’s a passionate,<br />

almost violent outpouring of emotion from Lady<br />

Macbeth, as she sings of the anticipated murder of<br />

Banquo, a ‘fatal deed that must be done’. This point in<br />

the opera marks the height of her power and the start of<br />

her downfall: it’s a moment that shows us how dark her<br />

desires are.<br />

Leonard Bernstein<br />

‘Somewhere’<br />

From West Side Story (1957)<br />

Bernstein’s West Side Story must be one of the most<br />

memorable <strong>Shakespeare</strong>-inspired settings by a classical<br />

composer. Though not technically an opera, a fair few<br />

opera singers have performed it – and even recorded it<br />

in the unfortunate case of soprano Kiri te Kanawa and<br />

tenor José Carreras. There are almost too many standout<br />

moments to mention in this modern-day Romeo and<br />

Juliet: Maria’s lively solo ‘I feel pretty’, the sassy fingerclicking<br />

‘Cool’ or the heartfelt duet ‘One hand, one<br />

heart’. But the song ‘Somewhere’ is hard to beat, and also<br />

takes its cues from Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto and,<br />

aptly enough, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet.<br />

Henry Purcell<br />

‘The Plaint’<br />

From The Fairy Queen (1692)<br />

It’s a little lament that’s one of the most moving<br />

moments of The Fairy Queen (1692), Purcell’s music<br />

for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In Act V, Oberon<br />

asks for ‘the plaint that did so Nobly move, When<br />

Laura Mourn’d for her departed Love’. He’s rewarded<br />

with melancholic music of true beauty, a melody that<br />

unfurls over a repeating bass line – one of Purcell’s party<br />

tricks. But carry on exploring the rest of this piece:<br />

Purcell didn’t simply write an opera but instead five<br />

masques – or semi-operas – to be performed between<br />

the acts of the play. It contains some of the British<br />

composer’s best music.<br />

Benjamin Britten<br />

‘I know a bank where the<br />

wild thyme blows’<br />

From A Midsummer Night’s Dream<br />

(1960)<br />

There’s something hypnotic, magical and ever so<br />

slightly menacing about this air, in which Oberon<br />

sings of his plan to drug Tytania with a magic herbal<br />

potion. Britten has carefully chosen his instrumental<br />

colours for his astute portrait of the king of the fairies:<br />

dark, sinuous cellos, a twinkling celesta, and a harp that<br />

seems to cast spells of enchanted notes. And then there’s<br />

the voice of Oberon himself. Britten wrote this role for<br />

a countertenor, a high male voice that has a strange,<br />

otherworldly quality quite unlike any other sound.<br />

Thomas Adès<br />

‘How good they are, how bright,<br />

how grand’<br />

From The Tempest (2004)<br />

This is a simply gorgeous quintet, in which five main<br />

characters finally join together in luminous music of<br />

reconciliation. It comes towards the end of Adès’s The<br />

Tempest, its lyricism hinted at in a love duet between<br />

Ferdinand and Miranda earlier on. Mozart was the<br />

master of the operatic ensemble, but here Adès steals<br />

one of Purcell’s tricks: he uses a repeated bass line<br />

that helps build the tension in this short but sublime<br />

moment.<br />

Rebecca has made a special Spotify playlist to go with her selections. Enjoy it here:<br />

https://play.spotify.com/user/1138333090/playlist/6xmKy9rQA9llmhUmRMItMp<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 37

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> Guide: Turkey<br />

Eastern<br />

Continuing our investigations<br />

into how <strong>Shakespeare</strong> is regarded<br />

in different countries around<br />

<br />

the historic meeting-place of<br />

East and West that is Turkey.<br />

Words: Cansu Kutlualp<br />

Promise<br />

38 SHAKESPEARE magazine

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> Guide: Turkey <br />

The Bosphorus has bewitched countless artists including<br />

ancient poets like Homer that inspired the Bard himself…<br />

T<br />

o William <strong>Shakespeare</strong>, the Turks were<br />

a strange people in a far-off land, an<br />

eastern empire largely unknown and<br />

seemingly irreconcilable. The orient<br />

stood for something frighteningly<br />

antagonistic that was also exotic and mysterious.<br />

This antagonistic attitude was mutual, but many<br />

aspects of European culture crossed over the Bosphorus<br />

to Turkey, and perhaps the most perpetual one has<br />

been <strong>Shakespeare</strong>. Both the Ottoman Empire and<br />

Turkish Republic – although with very different<br />

worldviews – took <strong>Shakespeare</strong> and interpreted him<br />

in different fashions. Over the centuries, <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

has become truly embedded into Turkish culture.<br />