You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Economist</strong> October 1st 2016 Finance and economics 69<br />

2 was modest, limiting production to<br />

32.5m-33m barrels per day, which is between<br />

0.7% and 2.2% below current output.<br />

Saudi Arabia’s production was likely to fall<br />

anyway as the winter approaches. <strong>The</strong><br />

agreement was also vague. Members will<br />

wait until their formal meeting in November<br />

to settle how the overall cut will be distributed<br />

amongthem. Nonetheless, within<br />

hours of the report, the price of oil rose by<br />

over 5% (before easing somewhat). To the<br />

question doesOPEC still matter, the market<br />

had given its own emphatic answer.<br />

Even OPEC-doubters will take note of<br />

what the agreement says about Saudi Arabia.<br />

<strong>The</strong> kingdom had insisted that it<br />

would cut output only if other producers<br />

followed suit. This insistence that OPEC cut<br />

as one or not at all brought it into direct<br />

conflict with other members like Iran.<br />

After EU sanctions were lifted earlier this<br />

year, Iran has been set on ramping its oil<br />

production as fast as possible. <strong>The</strong> Algiers<br />

agreement became possible only because<br />

Iran seems to have won this argument. It<br />

would be allowed to produce “at maximum<br />

levels that make sense”, said Saudi<br />

Arabia’s energy minister—a softer Saudi attitude<br />

that may reflect harder constraints at<br />

home. Low oil prices left the kingdom with<br />

a budget deficit of15% ofGDP last year.<br />

But will the agreement work? It has already<br />

moved the oil price. But then, one<br />

might argue, what doesn’t? <strong>The</strong> oil markets<br />

have been unusually volatile this year, as<br />

they struggle to find theirbearings in a new<br />

landscape, marked by slower global<br />

growth, resilient shale producers and the<br />

return of Iran. Amid great uncertainty<br />

about these changed fundamentals, commodity<br />

traders can lapse into secondguessing<br />

each other. Even if every trader<br />

suspects that OPEC in fact no longer does<br />

matter, OPEC will remain powerful until<br />

everyone knows everyone else agrees. 7<br />

Buttonwood<br />

Taking it to 11<br />

How central banks are distorting the corporate-bond and equity markets<br />

IN THE spoof “rockumentary”, “This is<br />

Spinal Tap”, Nigel Tufnel, the band’s guitarist,<br />

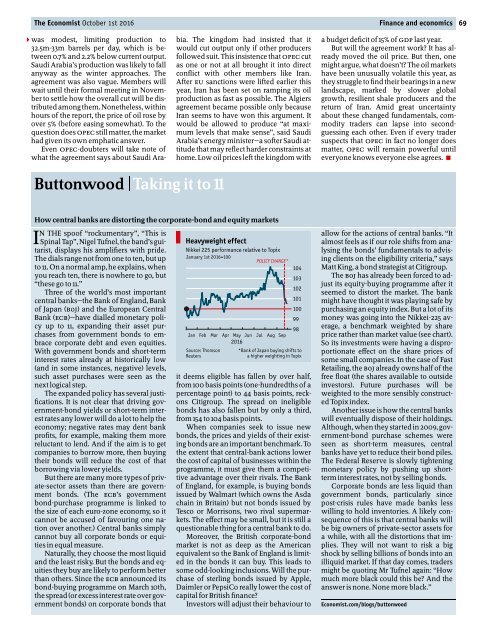

displays his amplifiers with pride. Nikkei 225 performance relative to Topix<br />

Heavyweight effect<br />

<strong>The</strong> dials range not from one to ten, but up<br />

January 1st 2016=100<br />

to 11. On a normal amp, he explains, when<br />

you reach ten, there is nowhere to go, but<br />

“these go to 11.”<br />

Three of the world’s most important<br />

central banks—the Bank of England, Bank<br />

of Japan (BoJ) and the European Central<br />

Bank (ECB)—have dialled monetary policy<br />

up to 11, expanding their asset purchases<br />

from government bonds to embrace<br />

corporate debt and even equities.<br />

With government bonds and short-term Source: Thomson<br />

Reuters<br />

interest rates already at historically low<br />

(and in some instances, negative) levels,<br />

such asset purchases were seen as the<br />

next logical step.<br />

<strong>The</strong> expanded policy has several justifications.<br />

It is not clear that driving government-bond<br />

yields or short-term interest<br />

rates any lower will do a lot to help the<br />

economy; negative rates may dent bank<br />

profits, for example, making them more<br />

reluctant to lend. And if the aim is to get<br />

companies to borrow more, then buying<br />

their bonds will reduce the cost of that<br />

borrowing via lower yields.<br />

But there are many more types of private-sector<br />

assets than there are government<br />

bonds. (<strong>The</strong> ECB’s government<br />

bond-purchase programme is linked to<br />

the size of each euro-zone economy, so it<br />

cannot be accused of favouring one nation<br />

over another.) Central banks simply<br />

cannot buy all corporate bonds or equities<br />

in equal measure.<br />

Naturally, they choose the most liquid<br />

and the least risky. But the bonds and equities<br />

they buy are likely to perform better<br />

than others. Since the ECB announced its<br />

bond-buying programme on March 10th,<br />

the spread (orexcessinterestrate overgovernment<br />

bonds) on corporate bonds that<br />

POLICY CHANGE*<br />

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep<br />

2016<br />

104<br />

103<br />

102<br />

101<br />

100<br />

*Bank of Japan buying shifts to<br />

a higher weighting in Topix<br />

it deems eligible has fallen by over half,<br />

from 100 basis points (one-hundredths of a<br />

percentage point) to 44 basis points, reckons<br />

Citigroup. <strong>The</strong> spread on ineligible<br />

bonds has also fallen but by only a third,<br />

from 154 to 104 basis points.<br />

When companies seek to issue new<br />

bonds, the prices and yields of their existing<br />

bonds are an important benchmark. To<br />

the extent that central-bank actions lower<br />

the cost of capital of businesses within the<br />

programme, it must give them a competitive<br />

advantage over their rivals. <strong>The</strong> Bank<br />

of England, for example, is buying bonds<br />

issued by Walmart (which owns the Asda<br />

chain in Britain) but not bonds issued by<br />

Tesco or Morrisons, two rival supermarkets.<br />

<strong>The</strong> effect may be small, but it is still a<br />

questionable thing for a central bank to do.<br />

Moreover, the British corporate-bond<br />

market is not as deep as the American<br />

equivalent so the Bank of England is limited<br />

in the bonds it can buy. This leads to<br />

some odd-looking inclusions. Will the purchase<br />

of sterling bonds issued by Apple,<br />

Daimler or PepsiCo really lower the cost of<br />

capital for British finance?<br />

Investors will adjust their behaviour to<br />

99<br />

98<br />

allow for the actions of central banks. “It<br />

almost feels as if our role shifts from analysing<br />

the bonds’ fundamentals to advising<br />

clients on the eligibility criteria,” says<br />

Matt King, a bond strategist at Citigroup.<br />

<strong>The</strong> BoJ has already been forced to adjust<br />

its equity-buying programme after it<br />

seemed to distort the market. <strong>The</strong> bank<br />

might have thought it was playing safe by<br />

purchasing an equity index. But a lot ofits<br />

money was going into the Nikkei-225 average,<br />

a benchmark weighted by share<br />

price rather than market value (see chart).<br />

So its investments were having a disproportionate<br />

effect on the share prices of<br />

some small companies. In the case of Fast<br />

Retailing, the BoJ already owns halfofthe<br />

free float (the shares available to outside<br />

investors). Future purchases will be<br />

weighted to the more sensibly constructed<br />

Topix index.<br />

Anotherissue is how the central banks<br />

will eventually dispose of their holdings.<br />

Although, when theystarted in 2009, government-bond<br />

purchase schemes were<br />

seen as short-term measures, central<br />

banks have yet to reduce their bond piles.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Federal Reserve is slowly tightening<br />

monetary policy by pushing up shortterm<br />

interest rates, not by selling bonds.<br />

Corporate bonds are less liquid than<br />

government bonds, particularly since<br />

post-crisis rules have made banks less<br />

willing to hold inventories. A likely consequence<br />

of this is that central banks will<br />

be big owners of private-sector assets for<br />

a while, with all the distortions that implies.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y will not want to risk a big<br />

shock by selling billions of bonds into an<br />

illiquid market. If that day comes, traders<br />

might be quoting Mr Tufnel again: “How<br />

much more black could this be? And the<br />

answer is none. None more black.”<br />

<strong>Economist</strong>.com/blogs/buttonwood