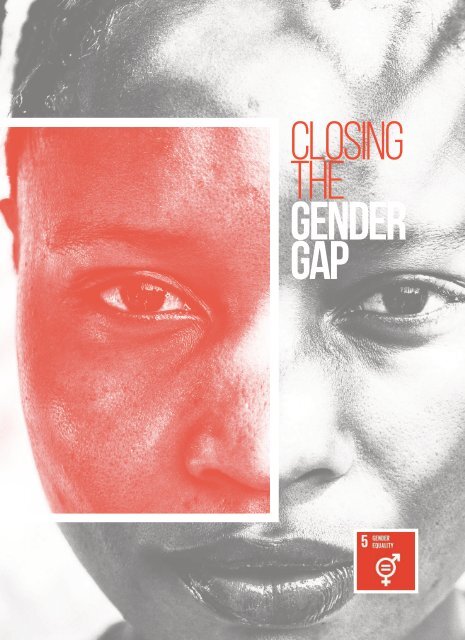

Closing the Gender Gap

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Closing</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong><br />

gender<br />

gap<br />

1

2

<strong>Closing</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong><br />

gender<br />

gap<br />

Copyright © 2016 Adam Smith International<br />

The material in this publication does not imply <strong>the</strong> expression of any opinion<br />

whatsoever on <strong>the</strong> part of Adam Smith International. Maps represent approximate<br />

border lines for which <strong>the</strong>re may not yet be full agreement. All reasonable<br />

precautions have been taken by Adam Smith International to verify <strong>the</strong> information<br />

contained in this publication. However, <strong>the</strong> published material is being distributed<br />

without warranty of any kind, ei<strong>the</strong>r expressed or implied.<br />

Results expressed in this publication are from Adam Smith International<br />

implemented programmes in 2014/5<br />

3

gend<br />

gen der<br />

/d ndə/<br />

noun<br />

3<br />

4

er<br />

<strong>the</strong> physical and/or social condition of<br />

being male or female<br />

5

6

7

Adam Smith International has spent <strong>the</strong> last 20 years dedicated to reducing aid<br />

dependency in some of <strong>the</strong> world’s most complex environments. We are wholly<br />

committed to sustainable development that addresses <strong>the</strong> underlying causes of<br />

poverty, but this will not be possible without addressing gender inequality.<br />

Equality benefits everyone, not just women. If girls’ attendance in secondary<br />

education increases by just 1%, a country’s entire GDP can increase by 0.3%;<br />

if women farmers have <strong>the</strong> same access to land and fertilisers as men, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

agricultural output could increase by 4%. This is why we are working to fix systemic<br />

challenges that cause gender disparity.<br />

A child’s access to education is a human right, yet 62 million girls are out of school.<br />

Pakistan is still a key country of concern, but we have already made significant<br />

progress towards increasing female enrolment in primary and secondary school.<br />

Recognising that some cultural norms require women to be educated separately from<br />

boys, we partnered with <strong>the</strong> Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to establish 1,000<br />

community schools for girls. We also launched a voucher scheme in six districts,<br />

enabling girls who cannot access government schools to attend low cost private<br />

schools. As a result of <strong>the</strong>se initiatives 42,000 more girls are now in primary school.<br />

A fur<strong>the</strong>r 406,712 girls have received stipends to support <strong>the</strong>ir secondary schooling.<br />

We also worked with <strong>the</strong> Government to monitor 28,000 public schools for <strong>the</strong> first<br />

time, resulting in a 26% increase in student attendance. In Punjab, we worked with<br />

<strong>the</strong> Government to provide free schooling for children in communities more than<br />

1km away from an existing school, and at <strong>the</strong> same time, to mobilise communities to<br />

demand better education for all children, especially girls.<br />

When we invest in women and compensate for historical and social disadvantages,<br />

countries prosper and poverty is reduced. All too often, women’s economic<br />

contributions go unquantified, <strong>the</strong>ir work is undervalued and <strong>the</strong>ir potential left<br />

unrealised. Our broad range of private sector development programmes are<br />

supporting adolescent girls and women obtain high quality skills and transition into<br />

formal employment and ensuring women are not excluded from economic markets.<br />

Our work in Nigeria alone has increased <strong>the</strong> incomes of over 393,000 women by an<br />

overall total of more than US $25million .<br />

Violence against girls and women has a profoundly negative impact on <strong>the</strong><br />

individual, family, community – and national development. Women who experience<br />

physical or sexual violence – over 1 in 3 globally – are less likely to complete <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

education, find it harder to earn a living, and are more vulnerable to maternal death.<br />

We are working to streng<strong>the</strong>n women’s representation, and professional capacity in<br />

key security and justice institutions in Afghanistan, Malawi and Somaliland.<br />

We are proud of our achievements so far, but recognise <strong>the</strong>re is more to do. Key<br />

areas of development, such as climate change, extractives and governance have<br />

historically been viewed as gender neutral, or even gender blind. We aim to go<br />

beyond what is expected of us as a development partner to ensure women play<br />

a central role in all our work. We have collected <strong>the</strong> thoughts and experiences of<br />

international experts and shared our lessons and case studies from across <strong>the</strong> world<br />

to contribute to <strong>the</strong> gender debate and, hopefully, show <strong>the</strong> possibility of equality, for<br />

<strong>the</strong> benefit of all.<br />

8

9

12<br />

34<br />

44<br />

56<br />

68<br />

10

ECONOMIC GROWTH<br />

EDUCATION<br />

GOVERNANCE<br />

JUSTICE & SECURITY<br />

CLIMATE & ENVIRONMENT<br />

11

ECONOMIC<br />

© Richard Broom<br />

12

GROWTH<br />

13

© R A Sanchez – istock<br />

49% of <strong>the</strong> world’s working women are in<br />

vulnerable employment.<br />

Less than 20% of landholders are women.<br />

Women spend at least 16 million hours a<br />

day collecting drinking water. Men spend<br />

just 6 million hours.<br />

ECONOMIES HAVE<br />

THE TYPES OF<br />

14

LAWS THAT RESTRICT<br />

JOBS WOMEN CAN DO<br />

15

Making markets work for women<br />

The global labour market is failing women. Only 50% of women are<br />

engaged in work worldwide. Women remain more vulnerable to<br />

exploitation and violence and are often unable to access lucrative<br />

industries. It doesn’t stop <strong>the</strong>re: globally, women earn about 23%<br />

less than men.<br />

Yet, women are a powerful economic resource. Increasing <strong>the</strong><br />

participation of women in <strong>the</strong> labour market can stimulate growth<br />

and increase household incomes worldwide, and as managers<br />

of household finances, boost <strong>the</strong> amount of money available for<br />

children’s education. Undoubtedly – everyone is better off when<br />

women earn.<br />

In agriculture, women make up 43% of <strong>the</strong> labour force in<br />

developing countries, but statistics often underestimate <strong>the</strong> amount<br />

of work women actually do. Despite many women being excluded<br />

from formal, big corporate markets, <strong>the</strong>re is a huge opportunity for<br />

women to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> economy of developing countries.<br />

To ensure change is sustainable, women must be included in<br />

economic markets. Making Markets Work for <strong>the</strong> Poor (M4P) – an<br />

approach which changes market systems to benefit <strong>the</strong> poor – aims<br />

to ensure <strong>the</strong> inclusion of women by breaking down barriers of<br />

market access such as unaffordability and lack of information.<br />

16

Chinumaya<br />

Darai, 28,<br />

grows tomatoes,<br />

but only for<br />

domestic consumption.<br />

She, like many in<br />

Dumsichaur – a small rural<br />

village in Nepal – is dependent<br />

on her husband’s income from<br />

overseas employment to provide for<br />

<strong>the</strong> rest of her family.<br />

This changed when she visited a local seed<br />

wholesale company. With 500sq metres of land,<br />

Chinumaya was advised to start testing off-season<br />

tomato cultivation and started planting higher quality<br />

seeds. “Now we get so much more income from this<br />

land because we know <strong>the</strong> right seeds to plant and when<br />

to plant <strong>the</strong>m. Next season, we are planning to expand tomato<br />

cultivation,” says Chinumaya.<br />

© narvikk – istock<br />

By helping a small, local business understand <strong>the</strong> needs of potential<br />

customers, local economies are stimulated to serve <strong>the</strong> poorest and<br />

enhance household economies. The SAMARTH-NMDP programme has<br />

increased <strong>the</strong> incomes of over 300,000 smallholder farmers and small-scale<br />

entrepreneurs to reduce poverty and empower women.<br />

www.samarth-nepal.com<br />

17

© Peeter Viisimaa – istock<br />

18

WOMEN DOING BUSINESS<br />

Nigeria has one of <strong>the</strong> lowest rates of female<br />

employment amongst countries with a similar gross<br />

national income – It is time for change.<br />

Nigeria is <strong>the</strong> economic powerhouse of West Africa. Though<br />

rich in natural resources – petroleum accounts for 85% of<br />

government revenues – it also boasts fast-growing telecoms and<br />

financial services industries. But not everyone is benefiting;<br />

women least of all.<br />

Around 6 million young Nigerian men and women enter <strong>the</strong><br />

job market annually, but only 10% secure a role in <strong>the</strong> formal<br />

economy, and just one third of <strong>the</strong>se are women.<br />

We speak to three businesswomen from across Nigeria to find<br />

out what needs to change.<br />

19

How did you become an<br />

entrepreneur?<br />

Laraba Tanko: I am 35. I was<br />

born into a peasant family in<br />

a remote village called Rafi-<br />

Roro. I only went to primary<br />

school, but now I have a<br />

market stall. I established<br />

my business 20 years ago,<br />

selling grains. I need to be<br />

an independent woman so I<br />

can set a good example to my<br />

three children.<br />

Hajia Saratu Umar: I grew<br />

up in Kano, in <strong>the</strong> north. I<br />

started selling food 40 years<br />

ago because, like Laraba,<br />

I wanted independence. It<br />

is not good if you have to<br />

ask your husband for every<br />

little thing. Today I am not<br />

feeling very well, but I am still<br />

at my stall because I need<br />

<strong>the</strong> money: it is better to<br />

experience pain in <strong>the</strong> body<br />

than pain in <strong>the</strong> mind.<br />

Olakitan Wellington: My<br />

first job was with a plastic<br />

manufacturing company. I<br />

was <strong>the</strong>re for two years and<br />

I learnt a lot about running a<br />

business. Now I run a financial<br />

literacy training business. I<br />

wanted to have control over<br />

my schedule so I would have<br />

enough time for my four<br />

children.<br />

Was it easy?<br />

Laraba: It was very difficult for<br />

me, being from a poor family.<br />

Since I was a child, I’ve had<br />

to work hard. The conditions<br />

at <strong>the</strong> market are really bad<br />

too. But recently our local<br />

government started providing<br />

basic facilities, including toilets<br />

and drinking water.<br />

Olakitan: A lot of women go<br />

into business without any plan<br />

or knowledge. I made <strong>the</strong> same<br />

mistake and had a terrible<br />

experience: tax men would<br />

come and threaten me with<br />

ridiculous bills; even bigger<br />

than my income! I had to pay<br />

and nearly lost all my money.<br />

What would encourage<br />

more women to get into<br />

business?<br />

Laraba: I would like to grow<br />

my business, but I don’t have<br />

<strong>the</strong> capital. Where do I get a<br />

loan? Banks won’t lend to us.<br />

Women are held back because<br />

we have no finance and it<br />

takes years for us to save.<br />

Olakitan: I would add that<br />

bureaucracy in banking<br />

procedures and high interest<br />

rates makes it difficult for us<br />

to get funding. We need to<br />

understand how to register<br />

our business and how to apply<br />

for a bank account; all of this<br />

is very complicated if you<br />

don’t have any education. I<br />

also want to know how best to<br />

reinvest my earnings so I can<br />

make more money.<br />

What are <strong>the</strong> challenges?<br />

Laraba: <strong>Gender</strong> inequality is<br />

a major challenge for us. We<br />

have more difficulty getting<br />

capital and our culture doesn’t<br />

allow us to do certain things.<br />

For example, we are not<br />

allowed to run our business<br />

late at night. We are also<br />

forced into doing menial jobs,<br />

such as cleaning and we don’t<br />

get paid as much as men.<br />

Olakitan: In Nigeria, a woman<br />

is expected to put her family<br />

first and she often can’t give<br />

her business <strong>the</strong> time and<br />

attention it needs. A man can<br />

go on a business trip without a<br />

second thought, but <strong>the</strong> woman<br />

has to think of her children and<br />

<strong>the</strong> home. Husbands also don’t<br />

like women working because<br />

<strong>the</strong>y think it might cause<br />

infidelity or expose <strong>the</strong>ir wife to<br />

sexual harassment.<br />

Has <strong>the</strong> status of women<br />

changed?<br />

Laraba: It is taxing to be a<br />

woman here, especially without<br />

education. I am always being<br />

reminded that it is a man’s<br />

world. Only with education and<br />

skills can we change <strong>the</strong> status<br />

of women. I think it is slowly<br />

improving.<br />

Hajia: I agree with Laraba;<br />

but life for women is better<br />

than before. Women are now<br />

employed; even old women<br />

like me are getting trained<br />

in things like midwifery. We<br />

can make three in one day. If<br />

we have a skill, we won’t be<br />

penniless and dependant on<br />

our husbands.<br />

www.gemsnigeria.com<br />

20

Nigeria is struggling to attract foreign<br />

investment due to security concerns and<br />

poor infrastructure. To combat growing<br />

poverty, Nigeria must find a way to improve<br />

its value chain and create wealth – for both<br />

women and men.<br />

One solution is to invest in small, local<br />

businesses. Establishing a small enterprise<br />

can be difficult in any country, but it is<br />

especially challenging in Nigeria where<br />

entrepreneurs have to contend with<br />

limited access to finance, high costs and<br />

excessive red tape in business registration<br />

procedures, and complex tax regulations.<br />

To help <strong>the</strong> Nigerian Government improve<br />

<strong>the</strong> business investment climate, <strong>the</strong> UK<br />

government and Adam Smith International<br />

are upgrading and streamlining legislation<br />

and administrative procedures to encourage<br />

<strong>the</strong> establishment and growth of small<br />

businesses.<br />

New payment systems, including direct-tobank<br />

payments, and simplified tax forms<br />

have been introduced. Tax-for-service<br />

agreements between trade associations<br />

and local government have been created,<br />

defining how government revenues should<br />

be reinvested in <strong>the</strong> economy. Publicity<br />

campaigns have been launched to ensure<br />

business owners are aware of <strong>the</strong>ir rights<br />

and responsibilities.<br />

In just six months, 517,000 women have<br />

seen an increase in <strong>the</strong>ir income. There<br />

is much more to be done, but change is<br />

happening.<br />

21

5,500,000<br />

Trips have been taken by women<br />

RESULTS<br />

through NIAF facilitated<br />

transport Networks in<br />

Nigeria<br />

22

Nigerian Infrastructure<br />

Advisory Facility<br />

The Nigeria Infrastructure<br />

Advisory Facility (NIAF) works<br />

across infrastructure sectors<br />

to remove bottlenecks to<br />

infrastructure delivery. It does<br />

this through mobilising expert<br />

teams to provide technical<br />

advice on policy and strategy,<br />

planning, project implementation<br />

and private sector investment.<br />

RESULTS<br />

Find out more:<br />

www.niafng.com<br />

23

RESULTS<br />

24

RESULTS<br />

,Women’s net<br />

incomes have been<br />

increased IN DRC,<br />

Nepal, Nigeria,<br />

Malawi, SIERRA<br />

LEONE & KENYA<br />

25

Amina Badi is a<br />

selfemployed<br />

Kenyan<br />

businesswoman.<br />

Based in<br />

Mombasa she<br />

now runs her own<br />

business thanks<br />

to training from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Kuza skills<br />

development<br />

programme.<br />

Finding work in Mombasa, my home city,<br />

is difficult. There aren’t many jobs and<br />

most people left school at a young age,<br />

like me.<br />

I’ve had few choices in life. I married young,<br />

but it didn’t work out. I argued with my<br />

husband all <strong>the</strong> time so I left with our small<br />

child. As a single parent, I desperately<br />

needed income. Cooking was something I<br />

could do, so I started selling food I made<br />

from home; many women do it. Almost all<br />

business people here sell on <strong>the</strong> street.<br />

It is now four years since I ventured into<br />

business, but anyone will tell you it is only<br />

courage that keeps you going. This kind of<br />

business can be very demoralising. At <strong>the</strong><br />

end of <strong>the</strong> day, if your food doesn’t sell you<br />

have to throw it away.<br />

Unemployment is a<br />

challenge that needs<br />

serious attention.<br />

In Kenya’s second<br />

largest city 86% of<br />

young people do not<br />

have a formal job.<br />

We hear Amina Badi’s<br />

story<br />

26

IT IS ONLY COURAGE<br />

that keeps you going<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r problem is being a woman. In Mombasa, we<br />

face more hurdles in business. We get harassed on<br />

<strong>the</strong> street which is frustrating and difficult to deal with.<br />

We get told to move and have to pay taxes which<br />

don’t exist; corruption here is very bad. There are also<br />

some cases where husbands are jealous of <strong>the</strong>ir wife’s<br />

success. They fear <strong>the</strong>ir wife could cheat if she is<br />

financially independent.<br />

Luckily, we have a strong community which runs a<br />

welfare group for women. This is where I learned about<br />

<strong>the</strong> Kuza business training programme. I thought I<br />

would not qualify because I was uneducated, but it<br />

turns out <strong>the</strong> training was actually for people like me.<br />

The Kuza scheme helped me determine profit and loss<br />

and taught me how best to manage my savings. Before<br />

I used to just sell homemade pastries, but now I have<br />

diversified my produce.<br />

By learning how to run a business, people like me<br />

have more chance of building a proper business:<br />

raising finance, getting insured, making contacts with<br />

bigger businesses, being protected from illegal taxes<br />

and being able to negotiate better with wholesalers.<br />

I don’t want to just<br />

survive, I want security &<br />

success.<br />

www.<strong>the</strong>kuzaproject.org<br />

27

Making Girls & Women<br />

The challenge of measuring gendered impact in<br />

private sector development<br />

Put simply, gender is no longer a “nice-to-have” - it’s a must-have. Recognising that women bear a<br />

disproportionate poverty burden relative to men, practitioners and donors have sought to integrate<br />

gender considerations into private sector development. But this is not so simple.<br />

In addition to economic factors, <strong>the</strong> rigidity of socially ascribed gender roles and women’s limited access<br />

to power, education, training and productive resources mean that it is often more difficult to reach, and<br />

positively impact women. This is particularly true when applying an approach such as Making Markets<br />

Work for <strong>the</strong> Poor (M4P). This approach – which changes economic market systems to benefit <strong>the</strong> poor<br />

– does not engage women directly, instead it seeks to facilitate gender-responsive systemic change by<br />

incentivising people to adopt inclusive business practices.<br />

Measuring <strong>the</strong> impact of private sector development programmes on poor women is equally complex.<br />

Whilst in most development sectors defining female beneficiaries is relatively simple, in private sector<br />

development, <strong>the</strong> generation, retention, and control of income makes this more complicated.<br />

Imagine <strong>the</strong>n, as part of a M4P programme, low-income farmers are connected to commercial farms to<br />

increase <strong>the</strong> income of <strong>the</strong> smallholder farmer.<br />

Unpacking<br />

<strong>the</strong> “Black<br />

Box”<br />

Whilst a woman cultivates her own land and sells <strong>the</strong> increased or higher-quality yield herself is likely to<br />

count as a beneficiary, what about a husband and wife team? Do both count as beneficiaries? Does it<br />

depend on <strong>the</strong> division of labour or <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong>ir contribution? Or is it automatically accrued by <strong>the</strong><br />

husband regardless of <strong>the</strong> wife’s contribution, in accordance with traditional norms? Does it matter who<br />

collects <strong>the</strong> revenue? Or how <strong>the</strong> money is distributed and used?<br />

Understanding <strong>the</strong> gendered impact of private sector development is challenging because households<br />

and (micro) enterprises often coalesce within poor communities. This means it is common for multiple<br />

individuals – often of different genders – to contribute to commercially productive activity.<br />

Some or all of <strong>the</strong>se individuals may benefit from interventions, though <strong>the</strong> ways in which <strong>the</strong>y benefit can<br />

vary: from improved access to agricultural products, land, or credit; to increased incomes; to a reduction<br />

in unpaid care work; to streng<strong>the</strong>ned agency at a family or community level. They may experience no<br />

benefit at all, or <strong>the</strong> intervention could cause harm.<br />

Whilst <strong>the</strong>re is no agreed approach to beneficiary reporting in private sector development, <strong>the</strong> most<br />

common practice is to count only <strong>the</strong> head of <strong>the</strong> family unit or enterprise unit, which is often <strong>the</strong> same<br />

individual. Problematically, this masks o<strong>the</strong>rs’ contribution to productive activity, including women, men,<br />

children, and labourers. This method almost always determines a male as <strong>the</strong> beneficiary.<br />

Who to<br />

Count?<br />

This approach is limiting and can distort <strong>the</strong> reality because impact on female members of male-headed<br />

family units are not captured in a programme’s monitoring and evaluation. Women are often counted as<br />

a beneficiary only if <strong>the</strong>y are divorced, widowed, or because of male migration. And although impacts<br />

are much easier to attribute in female-headed households, a true understanding requires a more acute<br />

exploration of mixed-sex, male-headed family and enterprise units to disentangle who benefits from (or is<br />

harmed by) <strong>the</strong> market system intervention, and how.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r programmes count all those in <strong>the</strong> family or enterprise unit, including paid or unpaid labourers.<br />

This approach assumes – often incorrectly – that any increase in unit income has positive and equal<br />

benefits for all those contained within it and simplifies <strong>the</strong> real gendered impact of <strong>the</strong> programme.<br />

28

Count<br />

Whilst alternative approaches do exist, for example, gendering time contribution to productive activities<br />

or household disaggregated income and expenditure surveys, <strong>the</strong>se are restrictively expensive,<br />

burdensome to deliver at scale, and often do not address o<strong>the</strong>r gendered data collection issues, such as<br />

concerns around <strong>the</strong> gender objectivity of survey respondents.<br />

A New<br />

Approach<br />

In response to <strong>the</strong>se challenges, Adam Smith International has developed a set of pioneering guidelines<br />

to improve <strong>the</strong> ability of practitioners to understand and measure <strong>the</strong> gendered impact of private sector<br />

development programmes. They comprise a three-step process that supports existing programmes to:<br />

• choose one approach to counting beneficiaries, apply this consistently across all interventions, and<br />

recognise <strong>the</strong> gendered implications of <strong>the</strong>ir given approach;<br />

• adapt existing standard measurement tools (including surveys, key informant interviews, and focus<br />

group discussion methodologies) to collect data designed to unpack intra-household gender<br />

dynamics as <strong>the</strong>y relate to income increase;<br />

• design and deliver qualitative analysis to add greater nuance to <strong>the</strong> sex-disaggregated beneficiary<br />

data reported at impact level.<br />

In using <strong>the</strong>se guidelines, SAMARTH, a Department for International Development funded marketdevelopment<br />

programme in Nepal, observed that in cases where households consider <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

to be male-headed, women are actually <strong>the</strong> primary contributors to vegetable farming, and have<br />

greater decision-making authority on how <strong>the</strong> income is spent. In this case, conventional measurement<br />

approaches would tend to count <strong>the</strong> male head of <strong>the</strong> household as <strong>the</strong> beneficiary, whereas <strong>the</strong><br />

approaches outlined in Adam Smith International’s guidelines more accurately attributed <strong>the</strong> benefits to<br />

women engaged in <strong>the</strong> household. This is because <strong>the</strong> measurement tools used enabled SAMARTH<br />

to capture more nuanced information about <strong>the</strong> relative contribution of men and women to <strong>the</strong><br />

increased income and <strong>the</strong> benefit derived from it. This has enabled SAMARTH to tell a much richer<br />

story of <strong>the</strong>ir impact on women and working-aged girls, particularly those in mixed-sex, maleheaded<br />

households.<br />

Ultimately <strong>the</strong>se guidelines will serve both to prove impact through monitoring and<br />

evaluation systems and to improve impact through intelligent, adaptive programme<br />

design across our private sector development portfolio.<br />

Empowerment<br />

Income Increase<br />

Access<br />

The Guidelines for Measuring <strong>Gender</strong>ed Impact in Private Sector<br />

Development will be launched at <strong>the</strong> Donor Committee for Enterprise<br />

Development’s Global Seminar 2016.<br />

Put simply, gender<br />

equality is no longer<br />

a nice-to-have<br />

it’s a must-have<br />

29

© zodebala – istock<br />

30

Men often benefit from mining, whilst <strong>the</strong><br />

social disruption falls heavily on women.<br />

There is a vast knowledge gap: <strong>the</strong> effect of<br />

mining on women is rarely known.<br />

Women are seldom consulted by mining<br />

companies before lands are leased: <strong>the</strong>y<br />

often lose <strong>the</strong>ir land and access to cash<br />

income from artisanal mining.<br />

Displaced and disposed, many women<br />

are stranded with no form of resettlement,<br />

rehabilitation or government assistance.<br />

31

Mining, men & migration<br />

Mining specialist Nellie Mutemeri talks about <strong>the</strong> adversities<br />

women face in a heavily male dominated industry<br />

32<br />

”<br />

What<br />

challenges have you<br />

faced in <strong>the</strong> mining industry?<br />

I’ve been in <strong>the</strong> mining sector<br />

all my professional life, so <strong>the</strong> issue<br />

of gender has always been present.<br />

Along <strong>the</strong> way, by nature of being<br />

a woman, you get drawn into <strong>the</strong>se<br />

discussions.<br />

I began my career in <strong>the</strong> UK in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1980’s as one of two girls in a<br />

class of 24, <strong>the</strong>n as a post-graduate<br />

student and later as a professional.<br />

I would go underground and<br />

you could see that people were<br />

shocked I was in a mine and not a<br />

miner!<br />

A few years ago, I was<br />

subjected to abuse on a trip<br />

to a mining site, but generally<br />

discrimination is based on attitude.<br />

Often you are made to feel like what<br />

you are doing is trivial and people<br />

make fun of gender initiatives. I sat<br />

in an interview and was once asked<br />

“Would you choose a team of women<br />

or a team of men?” A question I<br />

refused to answer. Women are not<br />

always taken seriously, particularly<br />

in mining companies.<br />

How do<br />

human rights issues<br />

feed into <strong>the</strong> mining industry?<br />

One could argue that women<br />

are excluded from accessing license<br />

opportunities to set up privatelyowned<br />

and regulated mines because of<br />

low levels of education. Without simple<br />

literary skills, women are unable<br />

to fill in <strong>the</strong> licensing form, and are<br />

subsequently held back from putting<br />

a case forward to access finances and<br />

own property. They start one step<br />

behind. In areas where this is <strong>the</strong> main<br />

source of work, women have to find<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r way to sustain <strong>the</strong>ir income.<br />

Women are left with so little choice<br />

that sex work often becomes <strong>the</strong> only<br />

option. With <strong>the</strong> growth of informal<br />

mining sector, <strong>the</strong> law has a large role<br />

to play to protect women’s livelihood<br />

opportunities. Women are literally on<br />

<strong>the</strong> periphery – sitting outside of <strong>the</strong><br />

mines selling food, or worse, <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

selling <strong>the</strong>ir bodies.<br />

You<br />

mention gender<br />

initiatives; could you<br />

elaborate?<br />

To shift attitudes <strong>the</strong>re needs<br />

to be a greater effort to have<br />

gender equality in <strong>the</strong> workplace.<br />

Women in mining is an issue that<br />

has little awareness because it<br />

is never talked about and <strong>the</strong><br />

fault lies in consultation – women<br />

are not consulted despite being<br />

stakeholders. Women are not given<br />

a voice and are excluded from<br />

policies and strategies. I see my<br />

role as an advocate for sector-wide<br />

change. As a respected practitioner,<br />

I think people are seeing <strong>the</strong><br />

value in bringing women into <strong>the</strong><br />

conversation.<br />

“<br />

Women are left<br />

with so little<br />

choice that<br />

sex work often<br />

becomes <strong>the</strong><br />

only option<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have.

Informal mining<br />

neglects safety standards and<br />

puts health at significant risk<br />

- are women aware of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

dangers?<br />

When women enter poorly<br />

regulated mines <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

for a mo<strong>the</strong>r who is responsible for<br />

feeding her family to die. In South<br />

Africa I saw a disused mine being<br />

illegally extracted by workers with no<br />

shoes, no helmet and using candles in<br />

an underground coal mine – a hazard,<br />

since an explosion could happen at any<br />

time. People were so desperate, men<br />

and women kept digging to get coal to<br />

sell despite <strong>the</strong> site being closed and<br />

unsafe.<br />

In Mali, women are working in<br />

mining sites with artisanal miners and<br />

extracting gold by rubbing mercury<br />

with <strong>the</strong>ir bare hands. I saw a woman<br />

sat with her baby breastfeeding<br />

with one hand and rubbing mercury<br />

concentration in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r – directly<br />

exposing her child to poison. She had<br />

no idea of <strong>the</strong> consequences.<br />

You’ve<br />

worked extensively across<br />

Africa; do you see <strong>the</strong><br />

issue of increasing female<br />

representation as continentwide,<br />

or are some countries<br />

making progress?<br />

There is a higher level of<br />

awareness in some countries.<br />

Tanzania is a model for o<strong>the</strong>r African<br />

countries; <strong>the</strong> Government is really<br />

getting involved and supporting <strong>the</strong><br />

mainstreaming of gender through<br />

platforms such as <strong>the</strong> Tanzania<br />

Women Miners Association. In a lot<br />

of o<strong>the</strong>r African countries <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is so little awareness that it is not<br />

even talked about, let alone on <strong>the</strong><br />

agenda.<br />

If mining companies have a<br />

gender equality charter to abide by<br />

<strong>the</strong>y could have targeted support for<br />

women, particularly on <strong>the</strong> technical<br />

side. This might stem <strong>the</strong> tide of<br />

women drifting from <strong>the</strong> technical<br />

fields to what is often referred to as<br />

softer skills, like community affairs.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> ground, women working<br />

in mines are exposed to severely<br />

dangerous environments, which<br />

raises human rights issues and<br />

abuses.<br />

Finally,<br />

migration is having a<br />

large impact on employment<br />

worldwide. What impact is this<br />

having on women in mining?<br />

Migration means communities<br />

are changing and people from<br />

different cultures and values are<br />

coming toge<strong>the</strong>r. Cultural beliefs and<br />

stigma can heavily affect women,<br />

particularly in informal mining<br />

communities, so women become more<br />

vulnerable to abuse.<br />

Dr Nellie<br />

Mutemeri<br />

is a senior<br />

specialist at<br />

AngloGold<br />

Ashanti and<br />

an Associate<br />

Professor at<br />

<strong>the</strong> Centre for<br />

Sustainability<br />

in Mining and<br />

Industry at <strong>the</strong><br />

University of<br />

Witwatersrand,<br />

South Africa.<br />

“<br />

Women working in mines are<br />

exposed to severely dangerous<br />

environments, which raises<br />

human rights issues and abuses.<br />

”<br />

33

34

Education<br />

35© Olli Stewart – greenshoot.org

An increase of 1% in girls’ secondary<br />

education attendance adds 0.3% to a<br />

country’s GDP.<br />

An extra year of secondary school can<br />

increase a girl’s potential income by 15 to<br />

25%.<br />

Every 3 seconds, a girl is forced or coerced<br />

to marry.<br />

If all girls had secondary education in sub-<br />

Saharan Africa and South and West Asia<br />

child marriage would fall by 64%.<br />

62 MILLION<br />

GIRLS ARE OUT OF SCHOOL<br />

36

37

Pakistan’s<br />

constitution commits <strong>the</strong> country to <strong>the</strong> provision of quality education<br />

for all children. Despite efforts to improve access, this commitment is<br />

far from being realised. A lack of reliable data makes it difficult to assess <strong>the</strong> number of out of<br />

school children, but estimates indicate an alarming 25%.<br />

Analysis of education indicators shows that access to schooling across <strong>the</strong> country is marked<br />

by deep disparities based on gender, geographic location and wealth. <strong>Gender</strong> inequality is<br />

evident in school enrolment: nearly 40% of primary school age girls are not attending school,<br />

compared to 30% of primary school age boys.<br />

There are a range of barriers to school attendance. One of <strong>the</strong> most important is finance.<br />

Children from poorer households in rural areas and urban slums have <strong>the</strong> highest probability of<br />

being out of school. Children belonging to low-income families are nearly six times more likely<br />

to be out of school compared to children growing up in richer households.<br />

Boys are affected, but girls are more: where families can afford to educate only one child, girls<br />

are often left behind. Financial barriers range from <strong>the</strong> inability to afford school fees (despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> provision of low fee private schools), to <strong>the</strong> inability to afford uniforms and school books,<br />

which have implications for children not only accessing schools but staying in school for longer.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r financial barrier is <strong>the</strong> opportunity cost of education: children who are not in school are<br />

able to support <strong>the</strong>ir families through labour wages or domestic work.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> more conservative parts of Pakistan, girls may have limited access to schooling because<br />

mobility is both a geographic and a cultural challenge. In a context where females are seldom<br />

seen outside <strong>the</strong>ir homes, <strong>the</strong>re may be cultural barriers that prevent girls travelling to school.<br />

Added to this limitation, is <strong>the</strong> distance between schools and homes, with girls discouraged<br />

from walking long distances to access schools because of safety concerns. The challenge is<br />

<strong>the</strong> need to raise awareness and change mindsets, but also to ensure that schools are located<br />

near <strong>the</strong> community, and that transport options are available.<br />

Some progress has been achieved. In Punjab, according to Nielsen Household Surveys, <strong>the</strong><br />

participation rate for girls has increased from 83% in November 2011 to 89% in June 2015.<br />

One successful approach, adopted in Punjab and in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, has involved<br />

partnering with <strong>the</strong> private sector. Under <strong>the</strong> DFID-funded Punjab Education Sector Programme<br />

2, civil society organisations and <strong>the</strong> Punjab Education Foundation provide free schooling for<br />

children across low performing districts of Punjab, in areas where <strong>the</strong>re are no schools within 1<br />

km of <strong>the</strong> community. The project also includes community mobilisation, to build awareness of<br />

<strong>the</strong> benefits of education for all children, especially girls.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rs 3%<br />

Health of child<br />

Special Education<br />

8%<br />

8%<br />

Reasons for a child<br />

not going to school in<br />

Punjab %<br />

Access<br />

16%<br />

38

The DFID-funded Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Education Sector<br />

Programme supports similar work. KP’s Elementary<br />

Education Foundation has established over 1,000 girls<br />

community schools to provide quality education to 48,767<br />

out of school children (of which 69% are girls) from families<br />

who are not willing or able to send <strong>the</strong>ir daughters to an<br />

unfamiliar and distant location to study, which is often <strong>the</strong><br />

case with government schools. After five years of schooling,<br />

girls receive a certificate, which is valid for continuing<br />

education in government schools.<br />

Within <strong>the</strong> same programme, a voucher scheme was<br />

launched which allowed out of school children living in<br />

areas without government schools, to obtain an education<br />

in nearby low cost, private schools free of cost. The scheme<br />

has been operational in six districts and has seen over<br />

17,000 out of school children enrol into private schools.<br />

Nearly half of <strong>the</strong>m are girls.<br />

Adam Smith International is implementing both<br />

programmes.<br />

Mindset<br />

30%<br />

Financial<br />

35%<br />

39

11,232<br />

NIGERIA<br />

RESULTS<br />

68,049<br />

KENYA<br />

40

RESULTS<br />

437,000<br />

PAKISTAN<br />

Number of girls<br />

benefiting from<br />

improved quality &<br />

access to education<br />

41

1,000<br />

GIRLS COMMUNITY<br />

SCHOOLS BUILT<br />

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa,<br />

North-West Pakistan<br />

RESULTS<br />

OVER<br />

28,000<br />

GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS<br />

MONITORED MONTHLY FOR<br />

THE FIRST TIME<br />

42

RESULTING IN A<br />

26%<br />

RESULTS<br />

INCREASE IN STUDENT PRESENCE<br />

43

© sadikgulec – istock<br />

44GOVERNANCE

45

average % of women<br />

parliamentarians<br />

41.5%<br />

Nordic countries<br />

Europe<br />

(excluding Nordic<br />

countries)<br />

23.6%<br />

26.3%<br />

Americas<br />

Middle East<br />

& North Africa<br />

22.2%<br />

Sub-Saharan<br />

Africa<br />

46

Asia<br />

18.5%<br />

16.1%<br />

68.8% Rwanda has<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> highest<br />

number of women<br />

parliamentarians<br />

worldwide.<br />

Pacific<br />

15.7%<br />

47

COMMUNITIES<br />

during<br />

Conflict<br />

© J Carillet – istock<br />

48

Girls and women in Syria face regular<br />

violence; many are exhausted trying to<br />

keep <strong>the</strong>ir family safe, whilst struggling<br />

to find food, water and shelter. They are<br />

often <strong>the</strong> main providers of <strong>the</strong> household, but<br />

during <strong>the</strong> brutal conflict women have also been<br />

subject to arrest, detention, physical abuse<br />

and torture. The rise of ISIS is also threatening<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir equality with reports suggesting it is<br />

“legitimate” for girls to be married to fighters<br />

at <strong>the</strong> age of nine and emphasising <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

role as wives, mo<strong>the</strong>rs and home-makers.<br />

Funded by <strong>the</strong> UK Conflict Pool and <strong>the</strong><br />

European Union, Adam Smith International<br />

has been working in partnership with<br />

communities in contested parts of Syria to<br />

deliver basic services. Such areas have no<br />

formal governance, limited public services and<br />

are plagued with hundreds of armed militia.<br />

The Tamkeen project, which means<br />

‘empowerment’ in Arabic, is providing<br />

grants which communities use to plan and<br />

implement projects. The purpose is to help<br />

communities to meet <strong>the</strong>ir basic needs<br />

and to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> emerging system<br />

of local governance in <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

Community representatives form Tamkeen<br />

committees which receive a block grant<br />

and training in community participation,<br />

budget prioritisation, project design<br />

and implementation to ensure that good<br />

governance principles inform <strong>the</strong> actions of<br />

<strong>the</strong> committee throughout <strong>the</strong> project cycle.<br />

The programme is not just delivering projects; it<br />

is stimulating <strong>the</strong> demand for good governance,<br />

holding decision-makers to account and<br />

reducing conflict by bringing fractured<br />

communities - both men and women - toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

for a common goal. Tamkeen committees work<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r with existing local councils and nongovernmental<br />

organisations to assess community<br />

needs: delivering services that benefit <strong>the</strong><br />

community. It is paving <strong>the</strong> way for when a<br />

legitimate, formal administration develops.<br />

Women & Power<br />

Even before <strong>the</strong> Syrian conflict, women were<br />

rarely involved in political decision-making in<br />

rural areas. Women were overlooked due to a<br />

lack of confidence in <strong>the</strong>ir abilities and social<br />

taboos around men and women working toge<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Tamkeen has begun to break <strong>the</strong> taboo of female<br />

involvement in governance. Women’s subcommittees<br />

are being formed in communities<br />

which have low female participation. This<br />

allows women to be included in <strong>the</strong> governance<br />

process without causing social disruption,<br />

and creates a space where Tamkeen can<br />

provide targeted mentoring and capacity<br />

development for women in its communities.<br />

A women’s sub-committee in Aleppo has<br />

designed and implemented a skills training<br />

centre. More than 100 women have signed<br />

up, courses are being delivered and a<br />

women-led management team is already<br />

planning how to expand its offering using<br />

fee revenue that is being collected.<br />

Overcoming<br />

stereotypes<br />

Initially, some committees begrudged women<br />

making decisions about public services: it was<br />

considered culturally inappropriate. Forcing<br />

committees to allocate some of <strong>the</strong>ir funds to<br />

a women’s sub-committee could have caused<br />

conflict and resentment towards women.<br />

Instead, Tamkeen provided an incentive: an<br />

additional US $5,000 per community as a<br />

matching grant for projects implemented by,<br />

and for, women. Since <strong>the</strong> community stands<br />

to gain an extra US $5,000 in funding, it has a<br />

strong motivation to allocate part of its existing<br />

grant to <strong>the</strong> women’s sub-committee. Now<br />

sceptical members of <strong>the</strong> community have<br />

begun to see <strong>the</strong> impact women can have on<br />

good government and societal development.<br />

Despite a bloody and unforgiving conflict,<br />

localised, modest positive change is happening.<br />

49

50<br />

CREATING A DEMAND FOR GOOD GOVERNANCE

ONGOING ONGOING impending: WE HOPE<br />

There is no legitimate national<br />

governance. Militia controls<br />

governorates and local councils are<br />

weak. Most governance structures<br />

are male-only and exclude women<br />

from decision making. Communities<br />

are left without any services and<br />

society disintegrates.<br />

Temporary Tamkeen Committees,<br />

which include women, are formed<br />

and partially merge with local<br />

councils to start streng<strong>the</strong>ning local<br />

governance. Public services are<br />

provided. There is popular demand<br />

for good governance in and around<br />

Tamkeen areas and traditionally<br />

male-only councils see <strong>the</strong> benefit of<br />

women in decision making positions.<br />

Local councils are streng<strong>the</strong>ned,<br />

adopt good governance and are<br />

better positioned to stand up to<br />

armed groups.<br />

A demand for good governance<br />

spreads and becomes more<br />

entrenched, it is replicated in more<br />

areas and more levels. It influences<br />

peace dialogue and <strong>the</strong> formation of<br />

new state/government structures.<br />

www.project-tamkeen.org<br />

51

www.project-tamkeen.org<br />

© Girish Chouhan – istock<br />

has dominated global headlines<br />

Syria for more than four years:<br />

chemical weapons, terrorism, refugees.<br />

It is a seemingly endless crisis.<br />

The big question, <strong>the</strong> one that keeps diplomats<br />

awake at night is: how do we make this stop?<br />

The answer is not simple. Syria has become<br />

a political and moral minefield; aligning<br />

and dividing countries across <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

Meanwhile, nine million Syrians are homeless.<br />

Many live in neighbouring refugee camps<br />

without any sense of belonging or legal<br />

employment opportunities, while o<strong>the</strong>rs choose<br />

to risk <strong>the</strong>ir life travelling in tiny, dangerous<br />

boats to seek asylum in Europe. But let us<br />

not forget those who are still living in one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> world’s most complex conflicts.<br />

Nadya is from rural Damascus. Like many<br />

Syrians, she is highly qualified. Nadya has<br />

a degree in philosophy and psychology<br />

and a diploma in education. She was also a<br />

former headmistress. She could have fled,<br />

but decided to stay. “I was a teacher when<br />

<strong>the</strong> revolution began. My school was bombed<br />

so I became an activist. I opened my own<br />

children’s centre in Mleha, my hometown.”<br />

After her school was attacked, her home was<br />

bombed too. Today, Mleha is unliveable.<br />

The carcasses of collapsed buildings<br />

litter roads and soldiers roam around<br />

deserted, hollowed blackened cars.<br />

“I lost everything. My family left. But I persevered.<br />

I moved to a nearby town and opened an<br />

education centre for women. At first, all <strong>the</strong><br />

teachers were volunteers, but <strong>the</strong>n I got funding<br />

and was able to pay <strong>the</strong>ir expenses. Now over 80<br />

students are enrolled. They tell me how my centre<br />

has given <strong>the</strong>m more control over <strong>the</strong>ir lives.”<br />

Tamkeen, a UK and EU-funded programme<br />

to increase good governance through service<br />

delivery in opposition-controlled Syria and is<br />

funding Nadya’s education centre. Tamkeen<br />

is also helping her re-establish <strong>the</strong> children’s<br />

centre she lost when Mleha was destroyed.<br />

52

Nadya<br />

“I have been able to re-establish <strong>the</strong><br />

children’s centre I had dreamt of.<br />

We call it ‘Home of Hope’ and we<br />

offer educational, recreational and<br />

psychosocial support for children.<br />

“We have trained over 250 teachers<br />

and hired psycho<strong>the</strong>rapists to offer<br />

psychosocial support to hundreds of<br />

children affected by poverty, depression,<br />

and fear. We have a small playground,<br />

called <strong>the</strong> ‘happiness corner’ but <strong>the</strong><br />

facilities are indoors to keep our children<br />

safe from bombing,” says Nadya.<br />

Nadya painted bright pictures all over<br />

<strong>the</strong> walls. “I want <strong>the</strong> centre to be an<br />

inspiring place for children to learn.<br />

A place where <strong>the</strong>y can heal and forget<br />

what is happening outside. You have<br />

to understand that we are under siege<br />

and have suffered immensely.<br />

“Life has become so difficult because even<br />

<strong>the</strong> basic necessities are scarce or too<br />

expensive. The price of a kilo of sugar has<br />

increased more than 10 times. People are so<br />

poor <strong>the</strong>y search for food in <strong>the</strong> rubble,” she<br />

says pointing beyond <strong>the</strong> centre’s gates.<br />

Nadya has been deeply affected by <strong>the</strong><br />

devastation that has unfolded in her country.<br />

But she is determined to stay and give<br />

<strong>the</strong> next generation a brighter future. We<br />

must not forget Nadya and <strong>the</strong> millions<br />

like her trying to stabilise Syria. It is <strong>the</strong><br />

one investment no one can dispute.<br />

Nadya is<br />

a former<br />

headmistress<br />

turned activist<br />

from rural<br />

Damascus.<br />

She started her<br />

own education<br />

centre for<br />

war affected<br />

children from<br />

Mleha.<br />

53

THE UNTOLD STORY OF WOMEN<br />

History often downplays a woman’s role and her contribution to society. Somalia’s<br />

history is no different: it focuses on unified stories of successful men, yet for<br />

women, different identities emerge depending on clan and region.<br />

A woman’s involvement in society often reflects her sense of responsibility, which<br />

changes during her lifetime. By documenting <strong>the</strong> stories of Somali women, one<br />

can see that a woman’s experiences are not collective and each individual’s<br />

experience is unique within a particular historical and social context.<br />

Women are also typically associated with traditional female activity<br />

and employment – mo<strong>the</strong>r, carer, wife, cook, nurse. Women<br />

are rarely in positions of political or economic power.<br />

The Somalia Stability Fund is a multi-donor fund which<br />

aims to change that. It is supporting <strong>the</strong> streng<strong>the</strong>ning<br />

of women’s leadership and participation in decision<br />

making and supporting women in <strong>the</strong> private sector<br />

through job placement schemes and youth<br />

entrepreneur grants. We hear from Suad Ismail,<br />

a young entrepreneur aiming to change <strong>the</strong><br />

traditional image of Somali women.<br />

Suad is not <strong>the</strong> kind<br />

of person to say no to<br />

a challenge: she plans to<br />

open <strong>the</strong> first women only<br />

gym in Somaliland’s capital.<br />

As an information technology graduate<br />

and previous owner of a kindergarten, Suad<br />

is one of many young Somalis trying to break<br />

<strong>the</strong> mould by starting up a business of her own.<br />

But Hargeisa is not conducive to business.<br />

The unemployment rate for 14-29 year olds is<br />

67%, a statistic that becomes even more worrying<br />

when over 70% of <strong>the</strong> population is under 35”.<br />

Suad’s enthusiasm and business acumen may not be enough<br />

to keep her ventures alive. Unlike start-up companies in <strong>the</strong> UK,<br />

Somali businesses do not have easy access to loans and support.<br />

In an atmosphere of financial uncertainty where banks<br />

are few and skittish, starting up a functioning corporation<br />

and finding <strong>the</strong> right staff is a huge challenge.<br />

This lack of financial literacy and capital is being addressed by projects such<br />

as <strong>the</strong> Somalia Stability Fund’s Youth Enterprise Initiative. The initiative, led by a<br />

consortium of Somali companies, is providing over 200 small businesses with financial<br />

training and selecting a smaller group of 15 to receive loans and fur<strong>the</strong>r support.<br />

The project ensures that <strong>the</strong> young Somali entrepreneurs know that <strong>the</strong> loans<br />

are Halal (in accordance with Islamic financial rules) and are part of a legitimate<br />

operation that will monitor and support <strong>the</strong>ir growing enterprises.<br />

The risk involved with starting up a Somali business for Suad is a painful reality. This new<br />

initiative will provide more women like Suad with <strong>the</strong> confidence needed to let <strong>the</strong>ir companies<br />

flourish and help to improve <strong>the</strong> homeland that <strong>the</strong>y will never stop believing in.<br />

“I have high hopes for <strong>the</strong> future,” says Suad, “soon things will change for <strong>the</strong> better”.<br />

www.stabilityfund.so<br />

54

IN SOMALIA<br />

I am <strong>the</strong> sister of <strong>the</strong> martyr.<br />

I am <strong>the</strong> aunt of <strong>the</strong> potato seller at <strong>the</strong> local market.<br />

I am <strong>the</strong> daughter of <strong>the</strong> local sheikh.<br />

I am <strong>the</strong> injured of <strong>the</strong> revolution. The protester. The jailed. The<br />

detained.<br />

I am <strong>the</strong> tortured. The exiled. The kidnapped. The raped.<br />

I am <strong>the</strong> veiled. The non-veiled. I am a beautiful soul.<br />

I am a Somali woman.<br />

My skin is of ebony and ivory. I am young by spirit. Old by<br />

experience.<br />

I am <strong>the</strong> pregnant. The wife. The single mo<strong>the</strong>r. The widow. The<br />

godobtiir and godobreeb tool<br />

forcing me into marriage as <strong>the</strong> compensation payment for ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

clan’s peace settlement.<br />

I am a Somali woman.<br />

Yet I am not a victim. I am a leader.<br />

Not a woman leader. But a leader who happens to be a woman.<br />

I clean up <strong>the</strong> streets of my nation. I rise up <strong>the</strong> past. The present<br />

and <strong>the</strong> future generations.<br />

I brought <strong>the</strong> Nobel Peace Prize to Somalia.<br />

I am a Somali woman.<br />

I speak out for my son at school.<br />

I speak up for my daughter in <strong>the</strong> madrasa.<br />

I pray for my ancestors and for my older son in jail. For my mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

in <strong>the</strong> hospital.<br />

I speak out for our artists whom <strong>the</strong>y keep bombing in <strong>the</strong>atres and<br />

on <strong>the</strong> streets.<br />

I am a Somali woman.<br />

I speak out for my mind. I am <strong>the</strong> pulse of <strong>the</strong> people.<br />

I live in <strong>the</strong> city. In <strong>the</strong> town. In <strong>the</strong> rural areas. In <strong>the</strong> suburbs. On<br />

<strong>the</strong> mountains. Along <strong>the</strong> borders.<br />

I am in Garowe. Mogadishu. Afgoye. Erigavo. Hargeisa. Galkayo.<br />

Bosaaso. Beletweyne. Badhan. Bocame. And every corner where <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is life and sound.<br />

I am a Somali woman.<br />

I am synonymous with strength and victory.<br />

I celebrate sisterhood. I celebrate mo<strong>the</strong>rhood.<br />

I boost <strong>the</strong> economy. I advance <strong>the</strong> technology. I give life to <strong>the</strong><br />

community.<br />

Do I deserve to be equal to you?<br />

Yes I do. Because I am a woman.<br />

A Somali woman.<br />

Sahro Kooshin<br />

55

JUSTICE<br />

© Amisom<br />

56

SECURITY<br />

57

© Amisom<br />

58

97% of military peacekeepers and 90% of<br />

police personnel are men.<br />

One in three women are likely to experience<br />

physical or sexual violence.<br />

The economic costs of violence against<br />

girls and women can be 3.7% of a country’s<br />

GDP.<br />

59

Somaliland<br />

FEMALE POLICE<br />

INVESTIGATORS<br />

TRAINED<br />

RESULTS<br />

OF THESE:<br />

RECEIVED FURTHER TRAINING AS A<br />

1 LEAD COUNTER-TERRORISM INVESTIGATOR<br />

RECEIVED FURTHER TRAINING AS CRIME<br />

5 SCENE EXAMINERS<br />

RECEIVED FURTHER TRAINING IN TRAINING<br />

2 OF TRAINERS<br />

RECEIVED FURTHER TRAINING IN CRIME<br />

SCENE AND FORENSIC PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

6<br />

FEMALE COUNTER-<br />

TERRORISM<br />

INVESTIGATORS<br />

TRAINED<br />

0<br />

1FEMALE POLICE<br />

INVESTIGATOR<br />

– INTELLIGENCE<br />

SPECIALIST<br />

TRAINED<br />

9<br />

FEMALE FINGERPRINT<br />

SPECIALISTS TRAINED<br />

SEXUAL OFFENCES TRAINING COURSE<br />

12<br />

POLICE OFFICERS<br />

6<br />

60<br />

MEMBERS OF THE ATTORNEY<br />

GENERAL’S OFFICE<br />

HAVE PARTICIPATED – 9 OF THE<br />

PARTICIPANTS WERE FEMALE

Malawi<br />

5 28<br />

OF THE<br />

INVESTIGATORS RECRUITED FOR<br />

OUR INVESTIGATOR TRAINING<br />

COURSE ARE WOMEN – HIGHER<br />

THAN THE OVERALL NATIONAL<br />

AVERAGE<br />

Afghanistan<br />

125<br />

LEGAL PROFESSIONALS TRAINED ON HOW TO<br />

HANDLE CASES INVOLVING FEMALE DETAINEES<br />

RESULTS<br />

THIS INCLUDES:<br />

3FEMALE COUNTER-<br />

TERRORISM PROSECUTORS<br />

FEMALE COUNTER-<br />

10 TERRORISM JUDGES<br />

1FEMALE HUMAN RIGHTS<br />

MONITOR<br />

61

Over <strong>the</strong> past 22 years <strong>the</strong> semi-autonomous region of Somaliland<br />

has steadily recovered from civil war to make impressive strides<br />

towards democratic governance and political stability. However<br />

<strong>the</strong> state remains fragile and faces substantial threats to safety<br />

such as violent crime, arms trafficking, and terrorism.<br />

We have been working with <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Interior and Somaliland<br />

Police Force to bring about institutional change and develop<br />

necessary counter-terrorist operational capabilities, whilst ensuring<br />

women – for <strong>the</strong> first time – are central to institutional development.<br />

62

63

Women, Peace & Security<br />

– a women’s issue?<br />

The landmark United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution<br />

1325 on Women, Peace and Security was <strong>the</strong> first resolution to<br />

formally recognise that women and girls are uniquely affected<br />

by conflict. Over <strong>the</strong> last 15 years, seven resolutions have followed<br />

and highlight how women play both a role in conflict prevention and<br />

resolution, as well as <strong>the</strong> maintenance of peace and security.<br />

Member states are required to provide better protection against<br />

sexual violence; improve <strong>the</strong> political participation of women;<br />

provide access to justice and services towards <strong>the</strong> elimination<br />

of gender discrimination; and to enhance <strong>the</strong> incorporation of<br />

gender into conflict processes. This includes peace negotiations,<br />

humanitarian planning, peacekeeping operations and post-conflict<br />

governance.<br />

The evidence that links gender equality with a country’s<br />

prospects for peace<br />

The work of Valerie Hudson and Mary Caprioli, authors of ‘Sex and<br />

World Peace’ and o<strong>the</strong>rs demonstrate that <strong>the</strong> best predictor of a<br />

state’s peacefulness is how well its women are treated. The larger<br />

<strong>the</strong> gender gap between <strong>the</strong> treatment of men and women, <strong>the</strong> more<br />

likely a country is to be involved in conflict, to be <strong>the</strong> first to resort to<br />

force in such conflicts and to experience higher levels of violence.<br />

Kathryn Lockett<br />

is a Senior<br />

Development<br />

Consultant<br />

specialising<br />

in gender,<br />

violence and<br />

conflict and a<br />

Senior <strong>Gender</strong><br />

and Conflict<br />

Adviser<br />

in <strong>the</strong> UK<br />

Stabilisation<br />

Unit.<br />

New analysis by <strong>the</strong> Centre on Conflict, Development and<br />

Peacebuilding also illustrates how <strong>the</strong> inclusion of women leads to a<br />

much higher rate of sustaining peace agreements. In addition, <strong>the</strong><br />

World Bank has long confirmed <strong>the</strong> link between gender equality<br />

and improved economic and development outcomes, which in turn<br />

has been found to indirectly increase a country’s stability through its<br />

impact on GDP.<br />

It is <strong>the</strong>refore unsurprising that UN Women identifies <strong>the</strong> need to<br />

include information on gender equality when undertaking conflict<br />

analysis. They recommend collecting country-level data on <strong>the</strong><br />

extent of gender equality under <strong>the</strong> law, <strong>the</strong> percentage of women<br />

in parliament, state responses to gender-based violence and female<br />

literacy rates, amongst o<strong>the</strong>rs. By monitoring gender equality in<br />

fragile and conflict-affected states, we learn crucial information not<br />

only about <strong>the</strong> situation for women in that context, but potentially<br />

about that country’s long-term risks of violence conflict.<br />

Protecting girls and women against sexual and gender-based<br />

violence in conflict is crucial to upholding human rights and<br />

preventing death, disability and lost quality of life for survivors, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

families and communities. Yet, beyond <strong>the</strong> protection agenda, more<br />

information in this area can provide us with essential information<br />

about <strong>the</strong> acceptability of violence and domination within a culture.<br />

64

Strong evidence exists to suggest that norms (held by<br />

both women and men) related to male authority, male<br />

sexual entitlement, acceptance of wife beating and female<br />

obedience increase <strong>the</strong> likelihood that individual men will<br />

engage in violence – and not just violence against women<br />

and girls. Recent findings by a UN multi-country study led<br />

by Partners4Prevention found that most men who had raped<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r man, or men, had also raped a female non-partner.<br />

Recent findings also show a culture of violence increases<br />

<strong>the</strong> likelihood of violence against women. This is particularly<br />

meaningful when we consider how sexualised violence against<br />

males during conflict, whilst increasingly being reported, is<br />

likely to be much higher than is generally assumed or publicly<br />

admitted.<br />

The same UN study confirmed <strong>the</strong> inter-generational effects of<br />

violence: that witnessing or experiencing domestic violence in<br />

childhood increases <strong>the</strong> likelihood of violence perpetration in<br />

later life, as individuals learn to use violence to exert influence<br />

and control. As such, working with families to tackle harmful<br />

gender norms, habits and behaviours to reduce sexual and<br />

gender-based violence against women and girls may offer<br />

an entry point to reduce violence more broadly. Much can<br />

be learned from <strong>the</strong> best practice of programmes that have<br />

successfully worked with communities to change harmful<br />

gender norms within communities, such as Promundo’s<br />

Programme H, research into young men showing genderequitable<br />

attitudes; Raising Voices’ SASA!, a programme<br />

designed to address <strong>the</strong> core driver of violence against<br />

women and Stepping Stones’ resources to raise awareness of<br />

gender issues.<br />

The promotion of women and girls’ rights in situations of<br />

conflict and fragility is a moral imperative that is all too<br />

relevant in <strong>the</strong> ongoing conflicts of today. Yet, women, peace<br />

and security’ is so much more than just a ’women’s issue.’<br />

Analysing indices of gender equality in a particular context<br />

can give us vital clues about <strong>the</strong> general level of inequality,<br />

intolerance and exclusion within a society.<br />

Collecting data on gender norms can also help us assess <strong>the</strong><br />

acceptability of violence and domination over o<strong>the</strong>rs. From<br />

such data, we can programme for change towards more<br />

stable and peaceful societies.<br />

65<br />

© Amisom

It’s<br />

time to redefine<br />

masculinity<br />

© D Berehulak – istock<br />

66<br />

I<br />

have worked in Somalia for several years.<br />

There have been huge efforts to focus on <strong>the</strong><br />

development of girls and women, and rightly<br />

so. Somalia’s maternal mortality rates are<br />

amongst <strong>the</strong> highest in <strong>the</strong> world, women are<br />

rarely involved in political decision-making and<br />

violence is not uncommon. But after <strong>the</strong>se years<br />

of working in Somalia I ask myself if this focus on<br />

women is enough to achieve gender equality? I<br />

don’t think so. Without understanding <strong>the</strong> Somali<br />

definition of masculinity we don’t stand a chance<br />

to reach equal opportunities for both men and<br />

women?<br />

Yes, promoting gender equality from a women’s<br />

perspective is important, but alone it will not<br />

take us all <strong>the</strong> way. A wife could start working,<br />

but what happens when her husband feels<br />

inadequate and uses domestic violence to assert<br />

his authority? A woman could be appointed as<br />

a Minister (to fill a quota), but will men respect<br />

her decisions? Businesses are encouraged to<br />

employ more women, but what happens when<br />

only menial ‘feminine’ jobs are offered? We have<br />

to be careful of development symbolism. We<br />

have to support men if we are to advocate for a<br />

new gender-friendly policy climate. If Somalia<br />

is expected to expand its definition on what it<br />

means to be a woman, it is crucial we redefine<br />

what it means to be a man.

The discourse of war<br />

War can have a tremendous impact on gender. In Europe wars have helped <strong>the</strong> process<br />

of gender equality, but in a conflict with fundamentalist ideology driving one of <strong>the</strong> parties<br />

this process is reversed. Al Shabaab – a predominately male Islamist militant group –<br />

plays into traditional stereotypes and has narrowed gender definitions. Al Shabaab has<br />

had a dominating influence and is based upon a religious discourse which makes it very<br />

hard for men and women to refine <strong>the</strong>mselves outside traditional roles – not least for <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

own security.<br />

In a context influenced by a dangerous insurgency, a strong counter narrative is needed<br />

to deflect a fundamentalist agenda. A new discourse will open up a space for both men<br />

and women to find <strong>the</strong>ir own personalities in a wider definition of what it means to be a<br />

man, and what it means to be a woman.<br />

Redefining masculinity – how can it be done?<br />

What can we learn from o<strong>the</strong>r countries? Let’s take Sweden. Granted, <strong>the</strong> cultural and<br />

social context is completely different, but <strong>the</strong> examples are relevant. In Sweden, women<br />

are given equal rights at work — and men equal responsibility at home. Many men no<br />

longer want to be defined just by <strong>the</strong>ir career or ability to provide; raising <strong>the</strong>ir children at<br />

home is as important. Sweden became <strong>the</strong> first country to replace maternity leave with<br />

parental leave, and businesses expect employees to take leave irrespective of gender.<br />

Hence, much of <strong>the</strong> gender equality has been achieved because family life and work has<br />

been easier to combine, both for men and women. Female employment rates and GDP<br />

surged as a result. <strong>Gender</strong> equality in Sweden is promoted as cultural pride and men are<br />

at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> gender-equality debate.<br />

Erik Pettersson<br />

is a former<br />

programme<br />

officer with<br />

<strong>the</strong> Embassy<br />

of Sweden in<br />

Nairobi.<br />