Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and ...

Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and ...

Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Function</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong><br />

<strong>receptor</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>haematopoiesis</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

cerebellar development<br />

Yong-Rui Zou*, Andreas H. Kottmann†, Masahiko Kuroda*,<br />

Ichiro Taniuchi*‡ & Dan R. Littman*‡<br />

* Division <strong>of</strong> Molecular Pathogenesis <strong>and</strong> ‡ Howard Hughes Medical Institute,<br />

Skirball Institute <strong>of</strong> Biomolecular Medic<strong>in</strong>e, New York University Medical Center,<br />

New York, New York 10016, USA<br />

† Department <strong>of</strong> Biochemistry <strong>and</strong> Molecular Biophysics, Columbia University<br />

College <strong>of</strong> Physicians <strong>and</strong> Surgeons, New York, New York 10032, USA<br />

.........................................................................................................................<br />

Chemok<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>receptor</strong>s are important <strong>in</strong> cell migration<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>flammation 1 , <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> functional lymphoid<br />

microenvironments 2 , <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> organogenesis 3 . The <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong><br />

<strong>receptor</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> is broadly expressed <strong>in</strong> cells <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong><br />

immune <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> central nervous systems 4,5 <strong>and</strong> can mediate<br />

migration <strong>of</strong> rest<strong>in</strong>g leukocytes <strong>and</strong> haematopoietic progenitors<br />

<strong>in</strong> response to its lig<strong>and</strong>, SDF-1 (refs 6–9). <strong>CXCR4</strong> is also a major<br />

<strong>receptor</strong> for stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)<br />

that arise dur<strong>in</strong>g progression to immunodeficiency <strong>and</strong> AIDS<br />

dementia 10 . Here we show that mice lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>CXCR4</strong> exhibit<br />

haematopoietic <strong>and</strong> cardiac defects identical to those <strong>of</strong> SDF-1deficient<br />

mice 3 , <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>CXCR4</strong> may be <strong>the</strong> only <strong>receptor</strong><br />

for SDF-1. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, fetal cerebellar development <strong>in</strong> mutant<br />

animals is markedly different from that <strong>in</strong> wild-type animals, with<br />

many proliferat<strong>in</strong>g granule cells <strong>in</strong>vad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> cerebellar anlage.<br />

This is, to our knowledge, <strong>the</strong> first demonstration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>volvement<br />

<strong>of</strong> a G-prote<strong>in</strong>-coupled <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>receptor</strong> <strong>in</strong> neuronal cell<br />

migration <strong>and</strong> pattern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> central nervous system. These<br />

results may be important for design<strong>in</strong>g strategies to block HIV<br />

entry <strong>in</strong>to cells <strong>and</strong> for underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g mechanisms <strong>of</strong> pathogenesis<br />

<strong>in</strong> AIDS dementia.<br />

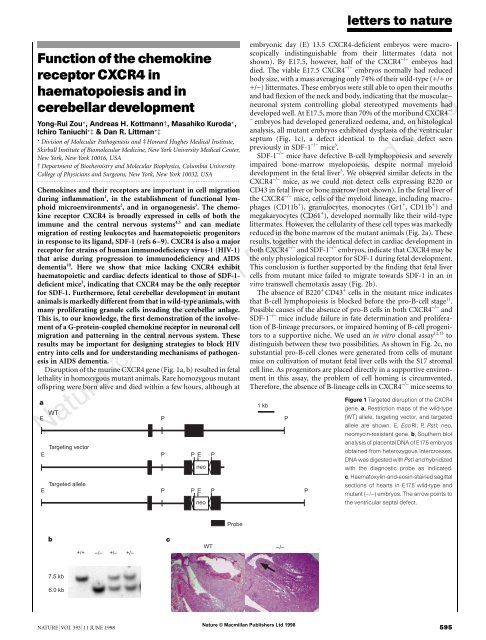

Disruption <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mur<strong>in</strong>e <strong>CXCR4</strong> gene (Fig. 1a, b) resulted <strong>in</strong> fetal<br />

lethality <strong>in</strong> homozygous mutant animals. Rare homozygous mutant<br />

<strong>of</strong>fspr<strong>in</strong>g were born alive <strong>and</strong> died with<strong>in</strong> a few hours, although at<br />

a<br />

WT<br />

E P<br />

Target<strong>in</strong>g vector<br />

E P P E P<br />

Targeted allele<br />

E P P E<br />

neo<br />

P<br />

b<br />

7.5 kb<br />

6.0 kb<br />

+/+ –/– +/– +/–<br />

c<br />

neo<br />

Probe<br />

WT –/–<br />

letters to nature<br />

embryonic day (E) 13.5 <strong>CXCR4</strong>-deficient embryos were macroscopically<br />

<strong>in</strong>dist<strong>in</strong>guishable from <strong>the</strong>ir littermates (data not<br />

shown). By E17.5, however, half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− embryos had<br />

died. The viable E17.5 <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− embryos normally had reduced<br />

body size, with a mass averag<strong>in</strong>g only 74% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir wild-type (+/+ or<br />

+/−) littermates. These embryos were still able to open <strong>the</strong>ir mouths<br />

<strong>and</strong> had flexion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> neck <strong>and</strong> body, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> muscular–<br />

neuronal system controll<strong>in</strong>g global stereotyped movements had<br />

developed well. At E17.5, more than 70% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> moribund <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/<br />

−<br />

embryos had developed generalized oedema, <strong>and</strong>, on histological<br />

analysis, all mutant embryos exhibited dysplasia <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ventricular<br />

septum (Fig. 1c), a defect identical to <strong>the</strong> cardiac defect seen<br />

previously <strong>in</strong> SDF-1 −/− mice 3 .<br />

SDF-1 −/− mice have defective B-cell lymphopoiesis <strong>and</strong> severely<br />

impaired bone-marrow myelopoiesis, despite normal myeloid<br />

development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fetal liver3 . We observed similar defects <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− mice, as we could not detect cells express<strong>in</strong>g B220 or<br />

CD43 <strong>in</strong> fetal liver or bone marrow (not shown). In <strong>the</strong> fetal liver <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− mice, cells <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> myeloid l<strong>in</strong>eage, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g macrophages<br />

(CD11b + ), granulocytes, monocytes (Gr1 + , CD11b + ) <strong>and</strong><br />

megakaryocytes (CD61 + ), developed normally like <strong>the</strong>ir wild-type<br />

littermates. However, <strong>the</strong> cellularity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se cell types was markedly<br />

reduced <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bone marrow <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mutant animals (Fig. 2a). These<br />

results, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> identical defect <strong>in</strong> cardiac development <strong>in</strong><br />

both <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− <strong>and</strong> SDF-1 −/− embryos, <strong>in</strong>dicate that <strong>CXCR4</strong> may be<br />

<strong>the</strong> only physiological <strong>receptor</strong> for SDF-1 dur<strong>in</strong>g fetal development.<br />

This conclusion is fur<strong>the</strong>r supported by <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that fetal liver<br />

cells from mutant mice failed to migrate towards SDF-1 <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong><br />

vitro transwell chemotaxis assay (Fig. 2b).<br />

The absence <strong>of</strong> B220 + CD43 + cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mutant mice <strong>in</strong>dicates<br />

that B-cell lymphopoiesis is blocked before <strong>the</strong> pro-B-cell stage 11 .<br />

Possible causes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> pro-B cells <strong>in</strong> both <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− <strong>and</strong><br />

SDF-1 −/− mice <strong>in</strong>clude failure <strong>in</strong> fate determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> proliferation<br />

<strong>of</strong> B-l<strong>in</strong>eage precursors, or impaired hom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> B-cell progenitors<br />

to a supportive niche. We used an <strong>in</strong> vitro clonal assay12,13 to<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>guish between <strong>the</strong>se two possibilities. As shown <strong>in</strong> Fig. 2c, no<br />

substantial pro-B-cell clones were generated from cells <strong>of</strong> mutant<br />

mice on cultivation <strong>of</strong> mutant fetal liver cells with <strong>the</strong> S17 stromal<br />

cell l<strong>in</strong>e. As progenitors are placed directly <strong>in</strong> a supportive environment<br />

<strong>in</strong> this assay, <strong>the</strong> problem <strong>of</strong> cell hom<strong>in</strong>g is circumvented.<br />

Therefore, <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> B-l<strong>in</strong>eage cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− mice seems to<br />

8<br />

Nature © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 1998<br />

NATURE | VOL 393 | 11 JUNE 1998 595<br />

1 kb<br />

P<br />

P<br />

Figure 1 Targeted disruption <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong><br />

gene. a, Restriction maps <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wild-type<br />

(WT) allele, target<strong>in</strong>g vector, <strong>and</strong> targeted<br />

allele are shown. E, EcoRI; P, PstI; neo,<br />

neomyc<strong>in</strong>-resistant gene. b, Sou<strong>the</strong>rn blot<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> placental DNA <strong>of</strong> E17.5 embryos<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed from heterozygous <strong>in</strong>tercrosses.<br />

DNA was digested with PstI <strong>and</strong> hybridized<br />

with <strong>the</strong> diagnostic probe as <strong>in</strong>dicated.<br />

c, Haematoxyl<strong>in</strong>-<strong>and</strong>-eos<strong>in</strong>-sta<strong>in</strong>ed sagittal<br />

sections <strong>of</strong> hearts <strong>in</strong> E17.5 wild-type <strong>and</strong><br />

mutant (−/−) embryos. The arrow po<strong>in</strong>ts to<br />

<strong>the</strong> ventricular septal defect.

letters to nature<br />

result from deficiency <strong>in</strong> commitment <strong>and</strong>/or proliferation <strong>of</strong> Bprogenitor<br />

cells.<br />

<strong>CXCR4</strong> is highly expressed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> thymus, particularly <strong>in</strong> immature<br />

CD4 + CD8 + cells 4 . However, T lymphopoiesis occurred normally<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mutant embryos at E17.5 (not shown). At this stage,<br />

most thymocytes are immature CD4 + CD8 + cells; few CD4 + CD8 − or<br />

CD4 − CD8 + mature T lymphocytes are present, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re is little or<br />

no emigration <strong>of</strong> thymocytes to <strong>the</strong> peripheral lymphoid organs.<br />

Emigration commences only after birth through a process <strong>in</strong> which<br />

<strong>the</strong> Gi prote<strong>in</strong>s are important 14,15 . As <strong>CXCR4</strong> expressed <strong>in</strong> rest<strong>in</strong>g T<br />

cells is coupled to G�i2 (refs 4, 10) <strong>and</strong> as mature T cells can migrate<br />

<strong>in</strong> response to SDF-1 stimulation 9 , migration <strong>and</strong> recirculation <strong>of</strong><br />

mature T cells might require signals delivered through <strong>CXCR4</strong>. To<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e whe<strong>the</strong>r maturation <strong>and</strong> emigration <strong>of</strong> thymocytes<br />

requires <strong>CXCR4</strong>, we engrafted <strong>the</strong> thymuses from E17.5 <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/−<br />

embryos under <strong>the</strong> kidney capsule <strong>of</strong> mice lack<strong>in</strong>g T-cell antigen<br />

<strong>receptor</strong> (TCR)-�. As <strong>the</strong> recipient mice are deficient <strong>in</strong> ��-T-cell<br />

development, any TCR-�� T cells detected <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> periphery are<br />

derived from <strong>the</strong> donor thymus. Our results <strong>in</strong>dicate that mature<br />

CD4 + CD8 − <strong>and</strong> CD4 − CD8 + T cells developed normally <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

implanted thymuses. Moreover, <strong>the</strong>se T cells efficiently populated<br />

<strong>the</strong> peripheral lymphoid organs, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g peripheral blood<br />

8<br />

(Fig. 2d), spleen, <strong>and</strong> mesenteric lymph nodes (results not<br />

shown). Thus, <strong>CXCR4</strong> has a negligible effect on thymocyte maturation<br />

<strong>and</strong> subsequent migration to lymphoid organs.<br />

As <strong>CXCR4</strong> messenger RNA is expressed <strong>in</strong> bra<strong>in</strong> 4 , we used <strong>in</strong> situ<br />

hybridization to study <strong>the</strong> embryonic mouse bra<strong>in</strong> at E13, E15 <strong>and</strong><br />

E18. <strong>CXCR4</strong> mRNA transcripts were found <strong>in</strong> many regions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Figure 2 Impaired <strong>haematopoiesis</strong> <strong>and</strong> SDF-1-<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

chemotaxis, but normal development <strong>of</strong> T cells, <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− mice. a, Flow-cytometric analysis <strong>of</strong> fetal liver<br />

cells <strong>and</strong> bone-marrow cells isolated from E17.5<br />

embryos. Cells were sta<strong>in</strong>ed with antibodies aga<strong>in</strong>st<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicated cell-surface markers (Gr1, CD11b, CD61<br />

<strong>and</strong> TER119), <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> percentages <strong>of</strong> cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> marked<br />

gates are <strong>in</strong>dicated. b, Transwell assay measurement <strong>of</strong><br />

SDF-1-<strong>in</strong>duced chemotaxis <strong>of</strong> fetal liver cells from E17.5<br />

mutant embryos (open circles) <strong>and</strong> wild-type littermates<br />

(filled circles). Flow-cytometric analysis showed that<br />

�90% <strong>of</strong> cells migrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> bottom chamber<br />

expressed myeloid-l<strong>in</strong>eage markers. Results from two<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent experiments are shown. c, In vitro clonal<br />

assay <strong>of</strong> pro-B-cell colony formation. Black bar, wild-type;<br />

white bar, <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− . Results represent <strong>the</strong> mean <strong>of</strong> four<br />

separate experiments. d, Flow-cytometric analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

thymocytes isolated from transplanted thymi <strong>of</strong> mutant<br />

<strong>and</strong> control embryos. B <strong>and</strong> T lymphocytes from <strong>the</strong><br />

peripheral blood <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> recipient mice were detected<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g antibodies aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>eage-specific markers<br />

CD45 (B220) <strong>and</strong> TCR-��. The percentage <strong>of</strong> cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

given quadrants is <strong>in</strong>dicated.<br />

Nature © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 1998<br />

596 NATURE | VOL 393 | 11 JUNE 1998

develop<strong>in</strong>g bra<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ret<strong>in</strong>a, olfactory epi<strong>the</strong>lium, olfactory<br />

bulb, hippocampus, cerebellum <strong>and</strong> sp<strong>in</strong>al cord (Fig. 3, <strong>and</strong><br />

data not shown). A similar pattern <strong>of</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> mRNA expression was<br />

found <strong>in</strong> rat bra<strong>in</strong> 5 . Expression was observed <strong>in</strong> regions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

cerebellum enriched <strong>in</strong> proliferat<strong>in</strong>g cells, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g neuroepi<strong>the</strong>lium,<br />

rhombic lip <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> external granule layer (EGL) (Fig. 3). We<br />

<strong>the</strong>n compared bra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mutant mice with those <strong>of</strong> wild-type<br />

littermates. Grossly, <strong>the</strong> structures <strong>of</strong> bra<strong>in</strong>s from <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− mice<br />

were comparable with those from wild-type animals (data not<br />

shown). However, closer exam<strong>in</strong>ation showed that <strong>the</strong> lam<strong>in</strong>ar<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cerebellum <strong>of</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− mice was aberrant.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> EGL was present, clusters <strong>of</strong> granule cells were<br />

found <strong>in</strong> ectopic positions, beneath <strong>the</strong> Purk<strong>in</strong>je cell layer or<br />

<strong>in</strong>term<strong>in</strong>gled with Purk<strong>in</strong>je cells (Fig. 4a, b). These abnormally<br />

placed cells expressed <strong>the</strong> Math 1 prote<strong>in</strong>, a marker <strong>of</strong> external<br />

granule cells 16 (Fig. 4c, d). All 20 mutant cerebella exam<strong>in</strong>ed showed<br />

normal pattern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> neuronal layers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> caudal part close to <strong>the</strong><br />

rhombic lip, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> defect <strong>in</strong> granule cell migration is<br />

probably a result <strong>of</strong> premature migration from <strong>the</strong> EGL ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

<strong>of</strong> abnormal lam<strong>in</strong>ar migration from <strong>the</strong> rhombic lip. The descend<strong>in</strong>g<br />

migration <strong>of</strong> EGL cells to form <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal granule layer (IGL) is<br />

normally a postmitotic event that occurs primarily after birth. In <strong>the</strong><br />

mutant mice, migration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> granule cells from <strong>the</strong> EGL was<br />

observed as early as E17.5, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>volved cells that cont<strong>in</strong>ued to<br />

proliferate, as assessed by <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>of</strong> bromodeoxyurid<strong>in</strong>e<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g a 2-h pulse labell<strong>in</strong>g (Fig. 4e, f). In contrast to <strong>the</strong> granule<br />

cells, <strong>the</strong> Purk<strong>in</strong>je cells were situated correctly <strong>in</strong> mutant embryos,<br />

as shown by sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with an anti-calb<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g antibody (not shown).<br />

The perpendicular migration <strong>of</strong> EGL cells may be directed by a<br />

Figure 3 Localization <strong>of</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> mRNA <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wild-type develop<strong>in</strong>g bra<strong>in</strong> as shown<br />

by <strong>in</strong> situ hybridization. A sense-cha<strong>in</strong> RNA probe used as a negative control gave<br />

no significant signal above background. a, Sagittal section show<strong>in</strong>g <strong>CXCR4</strong><br />

expression (darker shad<strong>in</strong>g) <strong>in</strong> neuronal precursors on <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

cerebellar anlage <strong>of</strong> E13.5 embryo (orig<strong>in</strong>al magnification, ×50). b, Sagittal section<br />

show<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>CXCR4</strong> expression <strong>in</strong> E15.5 cerebellum (×100). c, Transverse<br />

section <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lateral aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> E18.5 cerebellum (orig<strong>in</strong>al magnification, ×100).<br />

cb, Cerebellum; cp, choroid plexus; EGL, external granule layer; IV, fourth<br />

ventricle; IC, <strong>in</strong>ferior colliculus; NE, neuroepi<strong>the</strong>lium; PM, pia mater; PO, pons.<br />

letters to nature<br />

reciprocal <strong>in</strong>teraction between <strong>the</strong> granule neurons <strong>and</strong> Bergmann<br />

cells (<strong>the</strong> cerebellar radial glial cells). Although <strong>the</strong> postmitotic<br />

granule cells undergo differentiation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>duce Bergmann cell fibre<br />

extension, Bergmann cells provide a scaffold for neuronal migration<br />

<strong>and</strong> position<strong>in</strong>g 17,18 . Therefore, <strong>the</strong> dislocation <strong>of</strong> EGL <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mutant<br />

embryos early <strong>in</strong> cerebellar development could be a consequence <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> malformation <strong>of</strong> Bergmann cells. Sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with bra<strong>in</strong>-specific<br />

lipid-b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong> (BLBP) 19 , which labels radial glial cells,<br />

8<br />

showed that <strong>the</strong>se cells were properly localized with <strong>the</strong>ir fibres<br />

arranged <strong>in</strong> a normal configuration <strong>and</strong> orientation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/−<br />

mice (Fig. 4g, h). In some mutant embryos, <strong>the</strong>re was an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

number <strong>of</strong> neuronal cells along <strong>the</strong> Bergmann glial fibres (Fig. 4h).<br />

These results <strong>in</strong>dicate that <strong>CXCR4</strong>-mediated signall<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

required to prevent premature migration <strong>of</strong> proliferat<strong>in</strong>g granule<br />

cells <strong>in</strong>wards from <strong>the</strong> EGL. This could <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>duction <strong>of</strong><br />

Figure 4 Abnormal migration <strong>of</strong> cerebellar EGL cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> −/− embryos. a, b,<br />

Haematoxyl<strong>in</strong>-<strong>and</strong>-eos<strong>in</strong>-sta<strong>in</strong>ed sagittal sections, show<strong>in</strong>g dislocated cell<br />

aggregates underneath <strong>the</strong> Purk<strong>in</strong>je cell layer (arrow heads) <strong>in</strong> postnatal day 0<br />

mutant animals. c–h, Sagittal sections prepared from E17.5 embryos. Sections<br />

were sta<strong>in</strong>ed with antibodies aga<strong>in</strong>st Math1 (c, d), BrdU (e, f) or BLBP (g, h;<br />

countersta<strong>in</strong>ed with haematoxyl<strong>in</strong>). Arrowheads <strong>in</strong>dicate ectopic granule cells.<br />

Migrat<strong>in</strong>g granule cells from <strong>the</strong> EGL are viewed by higher magnification (arrows,<br />

f). CP, choroid plexus. PCL, Purk<strong>in</strong>je cell layer; RL, rhombic lip. Anterior is to <strong>the</strong><br />

right <strong>and</strong> dorsal to <strong>the</strong> top <strong>in</strong> each photograph. Orig<strong>in</strong>al magnifications: a, b, ×100;<br />

c, d, ×200; e–h, ×400.<br />

Nature © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 1998<br />

NATURE | VOL 393 | 11 JUNE 1998 597

letters to nature<br />

adhesive <strong>in</strong>teractions that prevent <strong>in</strong>ward cellular migration, similar<br />

to <strong>in</strong>duction <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>tegr<strong>in</strong>–lig<strong>and</strong> avidity <strong>in</strong> leukocyte–<br />

endo<strong>the</strong>lium <strong>in</strong>teractions 20 . Alternatively, <strong>CXCR4</strong>-mediated signals<br />

may desensitize cells to prevent <strong>in</strong>ward migration <strong>in</strong> response to<br />

different chemoattractants. Determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> mechanism <strong>in</strong>volved<br />

will require fur<strong>the</strong>r studies with isolated granule cells. It is unknown<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> lig<strong>and</strong> for <strong>CXCR4</strong> <strong>in</strong> cerebellar development is SDF-1,<br />

as no similar cerebellar abnormality was reported <strong>in</strong> SDF-1-deficient<br />

mice 3 . As signall<strong>in</strong>g through chemoattractant G-prote<strong>in</strong>coupled<br />

<strong>receptor</strong>s results <strong>in</strong> reorganization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cellular cytoskeleton<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> polarized cell movement 21 , such molecules are good<br />

c<strong>and</strong>idates for <strong>receptor</strong>s <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> neuronal cell migration <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

axon guidance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g nervous system. Fur<strong>the</strong>r studies<br />

will be required to determ<strong>in</strong>e whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong>s function like<br />

netr<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> ephr<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g guidance cues to axons 22,23 .<br />

Thus <strong>the</strong> <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>receptor</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> has several important<br />

functions <strong>in</strong> addition to <strong>in</strong>duc<strong>in</strong>g leukocyte chemotaxis. It is<br />

essential at <strong>the</strong> earliest stages <strong>of</strong> B-cell lymphopoiesis, <strong>in</strong> colonization<br />

<strong>of</strong> bone marrow by multipotential haematopoietic cells, <strong>in</strong><br />

cardiac septum formation, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> cerebellar neuronal layer formation.<br />

The observation that <strong>CXCR4</strong> acts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> both<br />

<strong>the</strong> immune system <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> central nervous system may be<br />

important, as <strong>CXCR4</strong> is a <strong>receptor</strong> for stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> HIV-1 that<br />

become prevalent with <strong>the</strong> onset <strong>of</strong> immunodeficiency <strong>and</strong> AIDS<br />

dementia 24,25 . HIV <strong>in</strong>fection may perturb <strong>CXCR4</strong> function <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

adult central nervous system, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> neurological<br />

manifestations. Fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

adult bra<strong>in</strong> will be required to determ<strong>in</strong>e whe<strong>the</strong>r it acts <strong>in</strong> virus<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

neurodegenerative disease. Our results also show that SDF-<br />

1 <strong>and</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> form a monogamous lig<strong>and</strong>–<strong>receptor</strong> pair dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

early haematopoietic <strong>and</strong> cardiac development. Block<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong><br />

with SDF-1 or with small molecule <strong>in</strong>hibitors <strong>in</strong>terferes effectively<br />

with HIV entry 6,7,26 . If <strong>CXCR4</strong> also has non-redundant functions <strong>in</strong><br />

adults, antagonists that block HIVentry may be harmful if <strong>the</strong>y also<br />

<strong>in</strong>terfere with <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g. An underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> functions<br />

<strong>of</strong> this <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>receptor</strong> will be essential for guid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

design <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>rapies aimed at block<strong>in</strong>g HIV entry <strong>in</strong>to cells. �<br />

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .<br />

Methods<br />

Targeted disruption <strong>of</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong>. The mouse <strong>CXCR4</strong> gene was cloned from a<br />

129/sv genomic DNA library (Stratagene). The target<strong>in</strong>g vector conta<strong>in</strong>ed 8.6<br />

kilobases (kb) <strong>of</strong> 5� <strong>and</strong> 0.8 kb <strong>of</strong> 3� homologous regions. The neomyc<strong>in</strong><br />

cassette flanked by LoxP sites 27 , used as a positive selection marker, was <strong>in</strong>serted<br />

<strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> second exon <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> gene at <strong>the</strong> KpnI site. The 3� homologous<br />

region was obta<strong>in</strong>ed by polymerase cha<strong>in</strong> reaction (PCR) us<strong>in</strong>g primers as<br />

follows: 5� primer: (5�-GCCGTCGACGTACCTCGCCATTGTCCACG-3�, <strong>and</strong><br />

3� primer 5�-GGCATCGATGTACCTCTAGACAGTCTCTTATATCTGGAAAA<br />

TG-3�). Chimaeric mice from three <strong>in</strong>dependent embryonic stem cells l<strong>in</strong>es<br />

transmitted <strong>the</strong> mutated <strong>CXCR4</strong> gene <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> germ l<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

Histology, bromodeoxyurid<strong>in</strong>e labell<strong>in</strong>g, immunohistochemistry <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

situ hybridization. Pregnant females were killed at <strong>in</strong>dicated time po<strong>in</strong>ts.<br />

Embryos were removed <strong>and</strong> kept <strong>in</strong> cold PBS, <strong>and</strong> placentas from<br />

correspond<strong>in</strong>g embryos were collected for genotyp<strong>in</strong>g. Heads <strong>and</strong> hearts <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> embryos were dissected, immersion-fixed <strong>in</strong> Bou<strong>in</strong>’s solution at room<br />

temperature or 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 �C, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n processed <strong>in</strong>to paraff<strong>in</strong><br />

section by rout<strong>in</strong>e procedure. Sagittal sections <strong>of</strong> 5 �m were sta<strong>in</strong>ed with<br />

haematoxyl<strong>in</strong>–eos<strong>in</strong>. To detect proliferat<strong>in</strong>g cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cerebellum, pregnant<br />

females were <strong>in</strong>jected with bromodeoxyurid<strong>in</strong>e (BrdU) (150 mg per kg body<br />

weight, <strong>in</strong>traperitoneally) <strong>and</strong> killed 2 h later. Embryos were isolated <strong>and</strong> fixed<br />

with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 �C, <strong>and</strong> 20-�m frozen sections were prepared.<br />

For immunohistochemical sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, sections were <strong>in</strong>cubated with different<br />

antibodies overnight at 4 �C. Primary antibodies used were as follows: anticalb<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(1:3,000, SWant), anti-BLBP (1:5,000, a gift from N. Heitz), anti-<br />

Math1 (1:500, a gift from J. Johnson), anti-BrdU (1:1, Amersham). Antibody<br />

b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g was detected us<strong>in</strong>g peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit antibody (Boehr<strong>in</strong>ger,<br />

1:100) or anti-mouse immunoglobul<strong>in</strong> (Sigma, 1:100). In situ<br />

hybridization us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> digoxigen<strong>in</strong> system (Boehr<strong>in</strong>ger) was done as<br />

described 28 . The <strong>CXCR4</strong> probe was generated by antisense transcription <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> 5� 580-base-pair BamHI complementary DNA fragment.<br />

In vitro clonogenic assay <strong>and</strong> flow cytometry. S<strong>in</strong>gle-cell suspension <strong>of</strong> fetal<br />

liver, bone marrow <strong>and</strong> thymus was prepared. A st<strong>and</strong>ard protocol was used for<br />

<strong>the</strong> detection <strong>of</strong> clonal pro-B cells 12,13 . Briefly, 96-well plates were prepared by<br />

seed<strong>in</strong>g 2,000 S17 cells 29 per well; after overnight culture, plates were irradiated<br />

(3,000 rads). Five hundred fetal liver cells were plated <strong>in</strong>to each well at a f<strong>in</strong>al<br />

volume <strong>of</strong> 200 �l <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Opti-MEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 15%<br />

8<br />

FCS (Hyclone), 5 � 10 � 5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, <strong>and</strong> 20 U ml −1 recomb<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

<strong>in</strong>terleuk<strong>in</strong>-7 (Gibco). The medium was changed every 4 days <strong>and</strong> lymphocyte<br />

clones were scored after 10–12 days. Cell identification was confirmed by<br />

fluorescence-activated cell sort<strong>in</strong>g (FACS) analysis by sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with antibodies<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st CD45 (B220) (phycoerythr<strong>in</strong>(PE)-conjugated) <strong>and</strong> CD43 (fluoresce<strong>in</strong><br />

isothiocyanate (FITC). Antibodies used to detect myeloid-l<strong>in</strong>eage cells were<br />

anti-CD11b(FITC) <strong>and</strong> anti-Gr1(PE); for <strong>the</strong> erythroid l<strong>in</strong>eage, anti-TER119<br />

(PE); for megakaryocytes, anti-CD61(FITC); for T-lymphoid cells, anti-CD4<br />

(FITC), anti-CD8 (PE) <strong>and</strong> anti-TCR��(FITC). All monoclonal antibodies<br />

used <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> flow cytometry were from PharM<strong>in</strong>gen.<br />

Fetal thymus transplantation. Fetal thymuses were removed from embryos at<br />

E17.5. Recipient mice (TCR-� −/− ) were anaes<strong>the</strong>tized with Avert<strong>in</strong> solution.<br />

Two thymic lobes from each embryo were placed under <strong>the</strong> kidney capsule.<br />

Three or four weeks after transplantation, recipients were killed, <strong>and</strong><br />

transplanted thymuses <strong>and</strong> lymphoid organs were dissected <strong>and</strong> analysed by<br />

flow cytometry.<br />

In vitro cell migration assay. 2 � 10 5 fetal liver cells <strong>in</strong> 100 �l were loaded <strong>in</strong>to<br />

each Transwell filter (3-�m pore filter Transwell, 24-well cell clusters, Costar).<br />

Filters were <strong>the</strong>n plated <strong>in</strong> each well conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 600 �l medium supplemented<br />

with different concentrations <strong>of</strong> SDF-1 as <strong>in</strong>dicated. After 3–4 h <strong>in</strong>cubation at<br />

37 �C, <strong>the</strong> upper chambers were removed, <strong>the</strong> cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bottom chamber were<br />

collected <strong>and</strong> counted, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir identities were confirmed by flow cytometry.<br />

Received 2 February; accepted 21 April 1998.<br />

1. Murphy, P. M. Chemok<strong>in</strong>e <strong>receptor</strong>s: structure, function <strong>and</strong> role <strong>in</strong> microbial pathogenesis. Cytok<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Growth Factor Rev. 7, 47–64 (1996).<br />

2. Förster, R. et al. A putative <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>receptor</strong>, BLR1, directs B cell migration to def<strong>in</strong>ed lymphoid<br />

organs <strong>and</strong> specific anatomic compartments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spleen. Cell 87, 1037–1047 (1996).<br />

3. Nagasawa, T. et al. Defects <strong>of</strong> B-cell lymphopoiesis <strong>and</strong> bone-marrow myelopoiesis <strong>in</strong> mice lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

CXC <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> PBSF/SDF-1. Nature 382, 635–638 (1996).<br />

4. Moepps, B., Frodl, R., Rodewald, H. R., Baggiol<strong>in</strong>i, M. & Gierschik, P. Two mur<strong>in</strong>e homologues <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

human <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>receptor</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> mediat<strong>in</strong>g stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha activation <strong>of</strong> Gi2 are<br />

differentially expressed <strong>in</strong> vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 27, 2102–2112 (1997).<br />

5. Jaz<strong>in</strong>, E. E., Soderstrom, S., Ebendal, T. & Larhammar, D. Embryonic expression <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mRNA for <strong>the</strong><br />

rat homologue <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fus<strong>in</strong>/CXCR-4 HIV-1 co-<strong>receptor</strong>. J. Neuroimmunol. 79, 148–154 (1997).<br />

6. Oberl<strong>in</strong>, E. et al. The CXC <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> SDF-1 is <strong>the</strong> lig<strong>and</strong> for LESTR/fus<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> prevents <strong>in</strong>fection by<br />

T-cell-l<strong>in</strong>e-adapted HIV-1. Nature 382, 833–835 (1996).<br />

7. Bleul, C. C. et al. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a lig<strong>and</strong> for LESTR/fus<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> blocks HIV-<br />

1 entry. Nature 382, 829–833 (1996).<br />

8. Aiuti, A., Webb, I. J., Bleul, C., Spr<strong>in</strong>ger, T. & Gutierrez-Ramos, J. C. The <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong> SDF-1 is a<br />

chemoattractant for human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells <strong>and</strong> provides a new mechanism to<br />

expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mobilization <strong>of</strong> CD34 + progenitors to peripheral blood. J. Exp. Med. 185, 111–120 (1997).<br />

9. Bleul, C. C., Fuhlbrigge, R. C., Casasnovas, J. M., Aiuti, A. & Spr<strong>in</strong>ger, T. A. A highly efficacious<br />

lymphocyte chemoattractant, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1). J. Exp. Med. 184, 1101–1109 (1996).<br />

10. Feng, Y., Broder, C. C., Kennedy, P. E. & Berger, E. A. HIV-1 entry c<strong>of</strong>actor: functional cDNA clon<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> a seven-transmembrane, G-prote<strong>in</strong>-coupled <strong>receptor</strong>. Science 272, 872–877 (1996).<br />

11. Hardy, R. R., Carmack, C. E., Sh<strong>in</strong>ton, S. A., Kemp, J. D. & Hayakawa, K. Resolution <strong>and</strong><br />

characterization <strong>of</strong> pro-B <strong>and</strong> pre-pro-B cell stages <strong>in</strong> normal mouse bone marrow. J. Exp. Med.<br />

173, 1213–1225 (1991).<br />

12. Hayashi, S. et al. Stepwise progression <strong>of</strong> B l<strong>in</strong>eage differentiation supported by <strong>in</strong>terleuk<strong>in</strong> 7 <strong>and</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r stromal cell molecules. J. Exp. Med. 171, 1683–1695 (1990).<br />

13. Delassus, S. & Cumano, A. Circulation <strong>of</strong> hematopoietic progenitors <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mouse embryo. Immunity<br />

4, 97–106 (1996).<br />

14. Chaff<strong>in</strong>, K. E. et al. Dissection <strong>of</strong> thymocyte signal<strong>in</strong>g pathways by <strong>in</strong> vivo expression <strong>of</strong> pertussis tox<strong>in</strong><br />

ADP-ribosyltransferase. EMBO J. 9, 3821–9829 (1990).<br />

15. Rudolph, U. et al. Ulcerative colitis <strong>and</strong> adenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> colon <strong>in</strong> G alpha i2-deficient mice.<br />

Nature Genet. 10, 143–150 (1995).<br />

16. Akazawa, C., Ishibashi, M., Shimizu, C., Nakanishi, S. & Kageyama, R. A mammalian helix-loop-helix<br />

factor structurally related to <strong>the</strong> product <strong>of</strong> Drosophila proneural gene atonal is a positive transcriptional<br />

regulator expressed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 8730–8738 (1995).<br />

17. Hatten, M. E. The role <strong>of</strong> migration <strong>in</strong> central nervous system neuronal development. Curr. Op<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Neurobiol. 3, 38–44 (1993).<br />

18. Hatten, M. E. & He<strong>in</strong>tz, N. Mechanisms <strong>of</strong> neural pattern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> specification <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

cerebellum. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 385–408 (1995).<br />

19. Feng, L., Hatten, M. E. & Heitz, N. Bra<strong>in</strong> lipid-b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong> (BLBP): a novel signal<strong>in</strong>g system <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g mammalian CNS. Neuron 12, 895–908 (1994).<br />

20. Spr<strong>in</strong>ger, T. A. Adhesion <strong>receptor</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> immune system. Nature 346, 425–434 (1990).<br />

21. Campbell, J. J. et al. Chemok<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> arrest <strong>of</strong> lymphocytes roll<strong>in</strong>g under flow conditions. Science<br />

279, 381–384 (1998).<br />

22. Seraf<strong>in</strong>i, T. et al. Netr<strong>in</strong>-1 is required for commissural axon guidance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g vertebrate<br />

nervous system. Cell 87, 1001–1014 (1996).<br />

23. Drescher, U., Bonhoeffer, F. & Muller, B. K. The Eph family <strong>in</strong> ret<strong>in</strong>al axon guidance. Curr. Op<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Neurobiol. 7, 75–80 (1997).<br />

24. Scarlatti, G. et al. In vivo evolution <strong>of</strong> HIV-1 co-<strong>receptor</strong> usage <strong>and</strong> sensitivity to <strong>chemok<strong>in</strong>e</strong>-mediated<br />

suppression. Nature Med. 3, 1259–1265 (1997).<br />

Nature © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 1998<br />

598 NATURE | VOL 393 | 11 JUNE 1998

25. Connor, R. I., Sheridan, K. E., Cerad<strong>in</strong>i, D., Choe, S. & L<strong>and</strong>au, N. R. Change <strong>in</strong> co<strong>receptor</strong> use<br />

correlates with disease progression <strong>in</strong> HIV-1-<strong>in</strong>fected <strong>in</strong>dividuals. J. Exp. Med. 185, 621–628 (1997).<br />

26. Donzella, G. A. et al. AMD3100, a small molecule <strong>in</strong>hibitor <strong>of</strong> HIV-1 entry via <strong>the</strong> <strong>CXCR4</strong> co-<strong>receptor</strong>.<br />

Nature Med. 4, 72–77 (1998).<br />

27. Gu, H., Zou, Y.-R. & Rajewsky, K. Independent control <strong>of</strong> immunogobul<strong>in</strong> switch recomb<strong>in</strong>ation at<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual switch regions evidenced through Cre-loxP-mediated gene target<strong>in</strong>g. Cell 73, 1155–1164 (1993).<br />

28. Schaeren-Wiemers, N. & Gerf<strong>in</strong>-Moser, A. A s<strong>in</strong>gle protocol to detect transcripts <strong>of</strong> various types <strong>and</strong><br />

expression levels <strong>in</strong> neural tissue <strong>and</strong> cultured cells: <strong>in</strong> situ hybridization us<strong>in</strong>g digoxigen<strong>in</strong>-labelled<br />

cRNA probes. Histochemistry 100, 431–440 (1993).<br />

29. L<strong>and</strong>reth, K. S. & Dorshk<strong>in</strong>d, K. Pre-B cell generation potentiated by soluble factors from a bone<br />

marrow stromal cell l<strong>in</strong>e. J. Immunol. 140, 845–852 (1988).<br />

Acknowledgements. We thank F. Hatan <strong>and</strong> M.-J. Sunsh<strong>in</strong>e for technical assistance; S. Vukmanovic for<br />

help with <strong>the</strong> thymic transplant experiments; J. Johnson <strong>and</strong> N. Heitz for anti-Math1 <strong>and</strong> anti-BLBP<br />

antibodies; K. Dorshk<strong>in</strong>d <strong>and</strong> R. R. Hardy for <strong>the</strong> S17 cell l<strong>in</strong>e; <strong>and</strong> G. Fishell, A. Joyner, M. Chao,<br />

C. Mason, S. Jung, V. KewalRamani <strong>and</strong> C. Davis for comments on <strong>the</strong> manuscript; Y.-R.Z. thanks H. Gu<br />

for his cont<strong>in</strong>uous support. This work was supported by an NIH grant (to D.R.L.). Y.-R.Z. is <strong>the</strong> recipient<br />

<strong>of</strong> a postdoctoral fellowship from <strong>the</strong> Irv<strong>in</strong>gton Institute, D.R.L. is an Investigator <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Howard Hughes<br />

Medical Institute.<br />

Correspondence <strong>and</strong> requests for materials should be addressed to Y.-R.Z. (e-mail: zou@saturn.med.nyu.edu).<br />

Histone macroH2A1<br />

is concentrated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>active X chromosome<br />

<strong>of</strong> female mammals<br />

Carl Costanzi & John R. Pehrson<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Animal Biology, School <strong>of</strong> Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, University <strong>of</strong><br />

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, USA<br />

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .<br />

In female mammals one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> X chromosomes is rendered almost<br />

completely transcriptionally <strong>in</strong>active 1,2 to equalize expression <strong>of</strong><br />

X-l<strong>in</strong>ked genes <strong>in</strong> males <strong>and</strong> females. The <strong>in</strong>active X chromosome<br />

is dist<strong>in</strong>guished from its active counterpart by its condensed<br />

appearance <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terphase nuclei 3 , late replication 4 , altered DNA<br />

methylation 2 , hypoacetylation <strong>of</strong> histone H4 (ref. 5), <strong>and</strong> by<br />

transcription <strong>of</strong> a large cis-act<strong>in</strong>g nuclear RNA called Xist 6–10 .<br />

Although it is believed that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>activation process <strong>in</strong>volves <strong>the</strong><br />

association <strong>of</strong> specific prote<strong>in</strong>(s) with <strong>the</strong> chromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>active X, no such prote<strong>in</strong>s have been identified 11 . We discovered<br />

a new gene family encod<strong>in</strong>g a core histone which we called<br />

macroH2A (mH2A) 12,13 . The am<strong>in</strong>o-term<strong>in</strong>al third <strong>of</strong> mH2A<br />

prote<strong>in</strong>s is similar to a full-length histone H2A, but <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

two-thirds is unrelated to any known histones. Here we show that<br />

an mH2A1 subtype is preferentially concentrated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>active X<br />

chromosome <strong>of</strong> female mammals. Our results l<strong>in</strong>k X <strong>in</strong>activation<br />

with a major alteration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nucleosome, <strong>the</strong> primary structural<br />

unit <strong>of</strong> chromat<strong>in</strong>.<br />

We exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> mH2A <strong>in</strong> mouse liver nuclei by<br />

immun<strong>of</strong>luorescence us<strong>in</strong>g antibodies aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> non-histone<br />

region <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mH2A1 subtypes, mH2A1.2 (Fig. 1a). Most<br />

hepatocyte nuclei were brightly sta<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong>se antibodies (Fig. 2a),<br />

although <strong>the</strong> nuclei <strong>of</strong> bile duct cells, endo<strong>the</strong>lial cells <strong>and</strong> connective<br />

tissue showed less sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (data not shown). Speckled<br />

sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was present through most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nuclei <strong>of</strong> both males<br />

<strong>and</strong> females. The nuclei <strong>of</strong> females, however, also had large, dist<strong>in</strong>ct<br />

mH2A-dense regions, which we name macrochromat<strong>in</strong> bodies<br />

(MCBs) (Fig. 2a, b). We found this sex difference <strong>in</strong> all mice we<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ed, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g several sets <strong>of</strong> sibl<strong>in</strong>gs, as well as <strong>in</strong> dog liver<br />

sections <strong>and</strong> human primary sk<strong>in</strong> fibroblasts (data not shown). We<br />

detected MCBs us<strong>in</strong>g several methods <strong>of</strong> tissue fixation <strong>and</strong> a variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> polyclonal antibodies, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g ones raised <strong>in</strong> rabbits or<br />

chickens <strong>and</strong> aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> non-histone region <strong>of</strong> mH2A1.1 (data<br />

not shown). MCBs were usually per<strong>in</strong>ucleolar, but little or no<br />

mH2A1.2 sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was detected <strong>in</strong> nucleoli, as assessed by doublelabel<br />

immun<strong>of</strong>luorescence with a monoclonal antibody aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong><br />

nucleolar prote<strong>in</strong> fibrillar<strong>in</strong> 14 (data not shown).<br />

To quantify <strong>the</strong> sex specificity <strong>of</strong> MCBs <strong>in</strong> liver parenchyma, we<br />

letters to nature<br />

identified complete nuclei <strong>in</strong> liver sections by confocal microscopy<br />

<strong>and</strong> assessed <strong>the</strong>ir MCB content (Fig. 2c). In mice, 85% <strong>of</strong> nuclei<br />

from females conta<strong>in</strong>ed MCBs, compared with less than 1% <strong>of</strong><br />

nuclei from males. A similar distribution was observed <strong>in</strong> dogs: 90%<br />

<strong>of</strong> female nuclei conta<strong>in</strong>ed MCBs compared with less than 1% <strong>of</strong><br />

male nuclei. The relative mH2A1 prote<strong>in</strong> content <strong>of</strong> female <strong>and</strong><br />

male mouse livers was similar (Fig. 1b), <strong>and</strong> previously estimated <strong>in</strong><br />

rat liver to be one mH2A per 30 nucleosomes 12 .<br />

The female specificity <strong>of</strong> MCBs suggested a relationship to Xchromosome<br />

<strong>in</strong>activation. We <strong>the</strong>refore localized MCBs relative to<br />

X chromosomes by sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g MCBs <strong>in</strong> female mouse liver sections by<br />

immun<strong>of</strong>luorescence <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n localiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> X chromosomes <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se sections by fluorescent <strong>in</strong> situ hybridization (FISH) with a<br />

DNA probe that ‘pa<strong>in</strong>ts’ mouse X chromosomes (X-pa<strong>in</strong>t) 15<br />

(Fig. 3a). Us<strong>in</strong>g confocal microscopy, we found that 99% <strong>of</strong><br />

MCBs colocalized to an X chromosome <strong>and</strong> 43% <strong>of</strong> X chromosomes<br />

colocalized to an MCB (Fig. 3b). In a control experiment, MCBs<br />

never colocalized with chromosome 4 (data not shown). The Xpa<strong>in</strong>t<br />

results also confirmed that hepatocyte nuclei with more than<br />

one MCB (Fig. 2a, c) were polyploid (Fig. 3a). The <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong><br />

polyploid nuclei was higher <strong>in</strong> older mice (data not shown).<br />

These results <strong>in</strong>dicate that <strong>the</strong> female-specific MCBs <strong>in</strong>volve one<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two X chromosomes. To determ<strong>in</strong>e which X chromosome is<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved, we exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> nuclear distribution <strong>of</strong> mH2A1 prote<strong>in</strong>s<br />

<strong>in</strong> female mice with one X-chromosome, male mice with two <strong>and</strong><br />

human Kl<strong>in</strong>efelter fibroblasts with four. X/0 mice are females with<br />

just one X chromosome (<strong>the</strong> active X), as is found <strong>in</strong> human<br />

Turner’s syndrome. The mH2A1.2 sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g pattern <strong>of</strong> X/0 liver<br />

sections was identical to that <strong>of</strong> normal males (data not shown).<br />

Sex-reversed mice have one normal X <strong>and</strong> one (designated Xsxr) that<br />

carries a translocated piece <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Y chromosome <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> sexdeterm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

locus16 . XXsxr mice are phenotypically male but have<br />

one active <strong>and</strong> one <strong>in</strong>active X chromosome. The mH2A1.2 sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> liver sections <strong>of</strong> XXsxr mice was identical to that <strong>of</strong> normal female<br />

mice (data not shown). F<strong>in</strong>ally, we analysed a human sk<strong>in</strong> cell l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

derived from a boy with Kl<strong>in</strong>efelter’s syndrome17 . The sex chromosome<br />

complement <strong>of</strong> this cell l<strong>in</strong>e is XXXXY (one active <strong>and</strong> three<br />

<strong>in</strong>active X chromosomes). Of <strong>the</strong>se nuclei, 63% had three MCBs<br />

each (Fig. 4a, b). We also observed preferential mH2A1.2 sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

three chromosomes <strong>in</strong> metaphase spreads prepared from <strong>the</strong>se cells<br />

8<br />

Figure 1 Specificity <strong>of</strong> mH2A antibodies. a, A diagram <strong>of</strong> mH2A1 subtypes.<br />

mH2A1.1 <strong>and</strong> 1.2 are identical apart from a segment generated by alternative<br />

splic<strong>in</strong>g (cross-hatched). The fragment used to generate <strong>the</strong> antibodies is<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicated by <strong>the</strong> solid bar. The H2A region is shaded; <strong>the</strong> segment rich <strong>in</strong> basic<br />

am<strong>in</strong>o acids is <strong>in</strong>dicated by plus signs. b, Western blot analysis <strong>of</strong> mouse liver<br />

nuclear extracts us<strong>in</strong>g antibodies raised aga<strong>in</strong>st mH2A1.1 (anti-1.1) <strong>and</strong> mH2A1.2<br />

(anti-1.2). The mH2A1.2 blot shows extracts from six littermates. Gel load<strong>in</strong>g was<br />

normalized aga<strong>in</strong>st core-histone content 12 .<br />

Nature © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 1998<br />

NATURE | VOL 393 | 11 JUNE 1998 599