You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

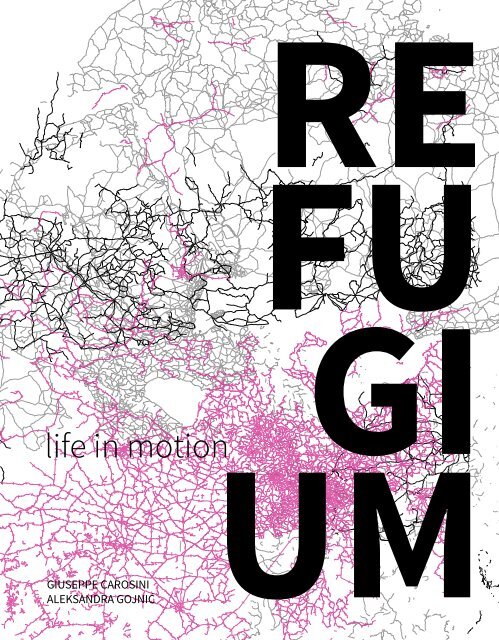

RE<br />

FU GI<br />

life in motion<br />

UM<br />

GIUSEPPE CAROSINI<br />

ALEKSANDRA GOJNIĆ

Politecnico di Milano<br />

Scuola di Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni<br />

Master of Science in Architecture<br />

R E F U G I U M - Life in Motion<br />

Supervisor : Massimiliano Spadoni<br />

Authors:<br />

Giuseppe Amedeo Carosini, 814274<br />

Aleksandra Gojnić, 814781<br />

December 2016

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

To professor Spadoni for his support and<br />

knowledge during this journey, and to<br />

Haitham who set us on this path.<br />

To our friends who kept a sense of humor<br />

when we had lost ours.<br />

To our families, for their unconditional<br />

support and care.

Home - Warsan Shire<br />

no one leaves home unless<br />

home is the mouth of a shark<br />

you only run for the border<br />

when you see the whole city running as well<br />

your neighbours running faster than you<br />

breath bloody in their throats<br />

the boy you went to school with<br />

who kissed you dizzy behind the old tin factory<br />

is holding a gun bigger than his body<br />

you only leave home<br />

when home won't let you stay.<br />

no one leaves home unless home chases you<br />

fire under feet<br />

hot blood in your belly<br />

it's not something you ever thought of doing<br />

until the blade burnt threats into<br />

your neck<br />

and even then you carried the anthem under<br />

your breath<br />

only tearing up your passport in an airport toilets<br />

sobbing as each mouthful of paper<br />

made it clear that you wouldn't be going back.<br />

you have to understand,<br />

that no one puts their children in a boat<br />

unless the water is safer than the land<br />

no one burns their palms<br />

under trains<br />

beneath carriages<br />

no one spends days and nights in the stomach of a truck<br />

feeding on newspaper unless the miles traveled<br />

means something more than journey.<br />

no one crawls under fences<br />

no one wants to be beaten,<br />

pitied<br />

no one chooses refugee camps<br />

or strip searches where your<br />

body is left aching,<br />

or prison,<br />

because prison is safer<br />

than a city of fire<br />

and one prison guard<br />

in the night<br />

is better than a truckload<br />

of men who look like your father<br />

no one could take it<br />

no one could stomach it<br />

no one skin would be tough enough

ABSTRACT<br />

The refugee crisis is an omnipresent polemic that is widespread<br />

throughout local and international news. Particularly within the recent<br />

war that has struck Syria, the influx of migrating refugees has hit an all<br />

time high, topping that even of the migration of refugees seen during<br />

WW2. With currently over 60 million people displaced within their own<br />

countries and globally, the problem is one of the most crucial facing<br />

humanity at this point in time. There is yet a further relevance to the<br />

situation which has now become too large to ignore. It is a problem<br />

that has not been dealt with on a historic level, with very little theory<br />

or concept developed around a larger solution to many of the issues<br />

that refugees face, further more there are predicted to be over 250<br />

million people who will become refugees within the next 20 years.<br />

The major problem which we face as architects when confronting<br />

this plight on a global level is that the reasons for people becoming<br />

refugees are often outside of our scope of work. This is due to the<br />

fact that they are produced by political, economical, natural disaster,<br />

famine, civil war or other reasons. It is also not our place to work with<br />

a god complex, prescribing a predetermined formula on how different<br />

cultures and different countries should deal with the influx of refugees<br />

within their cities, as again the number of role players from outside<br />

our field are too high. The scope of our work therefore falls between<br />

this. The focus on the Journey taken by the refugee to get from point<br />

A to point B. This is the part of the refugee’s struggle that is often most<br />

traumatic, with human trafficking, exploitation, rape, sinking boats<br />

and closed borders just some of the many obstacles that they face.<br />

9 REFUGIUM<br />

- AS ARCHITECTS WE MAKE A STAND -<br />

The solution lead to us taking the JOURNEY out of this migration and<br />

projecting this as a line encompassing the globe. This line utilizes the<br />

data analyzed as well as the lessons learned from the existing refugee<br />

camps in order to formulate a Utopic critique of the current crisis,<br />

geo-political contestations and lack of large scale intervention within<br />

the realm of architecture and urbanism. A series of doors will allow the<br />

refugees enter the structure and at the same time exit it, as long as the<br />

inhabitants behind the door are kind enough to unlock it.

01<br />

03<br />

STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

18 PRESENT<br />

40 PAST<br />

46 FUTURE<br />

DANGEROUS JOURNEY<br />

FOCUS - JOURNEY 56<br />

PREDATOR NATURE 62<br />

HUMANS AGAINST HUMANS 70<br />

BORDERS 72<br />

WALLS 74<br />

FORTIFIED EUROPE 80<br />

DEAD WORDS ON PAPER 82<br />

GODLESS PEOPLE AND INVISIBLE VICTIMS 86<br />

02

03<br />

LIFE IN LIMBO<br />

90 REFUGEE CAMPS<br />

94 CASE STUDIES:<br />

96 SAHRAWI CAMPS<br />

100 NAURU CAMP<br />

104 THE FAILURE OF REFUGEE CAMPS<br />

CONTENTS<br />

02<br />

04<br />

LIFE IN MOTION<br />

PROLOGUE 108<br />

MANIFESTO 110<br />

REFUGIUM 112<br />

THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS 118<br />

FROM POINTS TO A LINE 122<br />

NETWORK AND INFRASTRUCTURE 126<br />

ARCHITECTURE AS A DEVICE 140<br />

A TESTING GROUND 170

REFUGEE

CRISIS<br />

01<br />

STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

A look at the insurmountable data extending from the past to<br />

future of this ever evolving problem.

WHO IS A<br />

REFUGEE?<br />

WHAT IS THEIR<br />

CRISIS?

efugee<br />

/rɛfjʊˈdʒi/ meaning: a person who has been<br />

forced to leave their country in order to escape war,<br />

persecution, or natural disaster.<br />

From: French réfugié ‘gone in search of refuge’, past<br />

participle of ( se) réfugier, from refuge (see refuge).<br />

crisis<br />

/ἄπειρον/ meaning: - a time of intense difficulty<br />

or danger.<br />

-the turning point of a disease when an important<br />

change takes place, indicating either recovery or<br />

death.

16 REFUGIUM

PRESENT

18 REFUGIUM<br />

THE CURRENT STATE OF<br />

AFFAIRS<br />

alien<br />

/ˈeɪlɪən/ -a foreigner, especially one who is not a<br />

naturalized citizen of the country where he or she<br />

is living.<br />

allocate<br />

/ˈaləkeɪt/ - distribute according to a plan or set<br />

apart for a purpose.<br />

asylum<br />

/əˈsʌɪləm/ -the protection granted by a state to<br />

someone who has left their home country as a<br />

political refugee.<br />

One of the largest topics of discussion globally is without a doubt the<br />

current refugee crisis. The migration of Syrian refugees fleeing civil war<br />

and unlivable conditions within their country make up much of this<br />

spotlight. The statistics of refugees globally are much aligned with this,<br />

with Syrians making up the largest group of refugees by nationality<br />

with over 6.6 million Syrians internally and externally displaced. This<br />

though is not where the crisis stops. We are currently witnessing the<br />

largest and most rapid escalation ever in the number of people being<br />

forced from their homes globally since WWll. Iraq, Afghanistan, and<br />

Ukraine are embroiled in war, large swathes of Sub-Saharan Africa are<br />

wrought with persecution and disaster as is much of Southeast Asia.<br />

Much is made of the influx of millions of refugees to Europe, where<br />

people are caught in such a state of desperation that they are willing<br />

to take on the perilous journey to reach the EU, full knowing that there<br />

are many who never make it. The tragedy here though, although not<br />

to be diminished, is only telling of part of the story. Refugee camps<br />

worldwide are bursting at the seams and have become places of disenchantment<br />

and squalor. Hundreds of thousands of people are lost<br />

to human trafficking or abducted and sold into slavery. The refugee<br />

crisis is also something that will not ‘blow over’ with the passing of<br />

time, it is a fundamental issue that is threating to exponentially increase<br />

unless thought is given to this issue and the issues around it are<br />

highlighted in their entirety.<br />

Globally war is often seen as the number one generating factor of<br />

refugees but as climate change catches up with the human race, so<br />

too are the number of climatic refugees ever on the rise. This trend is<br />

so much so that the number of environmental refugees by 2050 will<br />

far outweigh that of refugees of any other cause. This is not a problem<br />

that is something that can be solved overnight, but needs to be<br />

addressed with the utmost urgency or the consequences will cripple<br />

the world in its entirety. Current political policies are one of the main<br />

issues that need to be addressed in order to generate viable alternatives<br />

to what ultimately is a crisis that revolves around the utmost care<br />

in procedural planning in order to reduce the impacts of the problem.<br />

Further than reading highly charged headlines in newspapers or<br />

watching politically motivated clips on the news often depicting refugees<br />

as a problem, intensifying xenophobia among the populous, the<br />

refugee crisis needs to fundamentally studied and understood by all.<br />

Europe itself has been quick to shut its doors to refugees, forgetting<br />

how after WW2 many of its own people were taken in as refugees by<br />

many of the countries that are seeking refuge on its doorstep now. The<br />

crisis is an extremely complex issue which will be objectively unpacked<br />

and analyzed in order to derive possible potentialities to work within<br />

when it comes to solving this problem.

60 MIL<br />

ION<br />

People displaced worldwide<br />

DISPLACED PEOPLE<br />

The current epoch - Largest Refugee<br />

Crisis to date since WWll. With over 60<br />

million accounted for displaced people,<br />

the population of potential refugees is<br />

identical to that of the entire population<br />

of Italy - Figure below.<br />

The countries currently hosting the<br />

largest number of refugees in Europe by<br />

official granted claims barely scratches<br />

the surface of this problem.<br />

Germany Sweden France Italy Switzerland UK<br />

47,555 33,025 20,640 20,630 15,575 14,065<br />

Total claims granted by country<br />

19 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE

20 REFUGIUM<br />

A PROBLEM WITH INFINITE<br />

BEGINNINGS<br />

A GLOBAL CRISIS<br />

The source of refugees is near impossible to determine<br />

as the cause, origin and destination of refugees are<br />

always in a constant state of flux. Numbers of refugees<br />

from different parts of the globe vary depending on<br />

the current situation or conditions which would force<br />

someone into exile in the first place. The graphic on<br />

the right is a great example of this. Here one can see a<br />

comparative diagram, exploring the number of refugees<br />

by country throughout the world. The exhaustive list is<br />

testament to the fact that the starting point of this problem<br />

is an equation without a solution.<br />

Since the establishment of the United Nations High<br />

Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on 14 December<br />

1950, numerous policies have been put in place and<br />

formed in order to create discourse and give structure<br />

to the complexities of these issues. The term refugee is<br />

often used in two different contexts: 1) in everyday usage<br />

it refers to a displaced person who flees their home<br />

or country of origin, 2) in a more specific context it refers<br />

to a displaced person who was given refugee status in<br />

the country of asylum. In between these two stages the<br />

person may have been an asylum seeker. The UNHCR<br />

has developed a set of basic rights to which a person<br />

who has officially been granted the status of refugee is<br />

entitled to.<br />

1.<br />

RIGHT OF RETURN<br />

Even in a supposedly “post-conflict” environment, it is not a<br />

simple process for refugees to return home. The UN Pinheiro<br />

Principles are guided by the idea that people not only have the<br />

right to return home, but also the right to the same property. It<br />

seeks to return to the pre-conflict status quo and ensure that<br />

no one profits from violence. Yet this is a very complex issue<br />

and every situation is different; conflict is a highly transformative<br />

force and the pre-war status-quo can never be reestablished<br />

completely, even if that were desirable (it may have<br />

caused the conflict in the first place). Therefore, the following<br />

are of particular importance to the right to return.<br />

2.<br />

RIGHT TO NON-REFOULEMENT<br />

Non-refoulement is the right not to be returned to a place of<br />

persecution and is the foundation for international refugee<br />

law. The right to non-refoulement differs from the right to<br />

asylum. To respect the right to asylum, states must not deport<br />

genuine refugees. In contrast, the right to non-refoulement<br />

allows states to transfer genuine refugees to third party<br />

countries with respectable human rights records. The portable<br />

procedural model, emphasizes the right to non-refoulement<br />

by guaranteeing refugees three procedural rights (to a verbal<br />

hearing, to legal counsel, and to judicial review of detention<br />

decisions) and ensuring those rights in the constitution. This<br />

proposal attempts to strike a balance between the interest of<br />

national governments and the interests of refugees.<br />

3.<br />

RIGHT TO FAMILY REUNIFICATION<br />

Family reunification (which can also be a form of resettlement)<br />

is a recognized reason for immigration in many countries. Divided<br />

families have the right to be reunited if a family member<br />

with permanent right of residency applies for the reunification<br />

and can prove the people on the application were a family unit<br />

before arrival and wish to live as a family unit since separation.<br />

If the application is successful this enables the rest of the family<br />

to immigrate to that country as well.<br />

4.<br />

RIGHT TO TRAVEL<br />

Those states that signed the Convention Relating to the Status<br />

of Refugees are obliged to issue travel documents (i.e. “Convention<br />

Travel Document”) to refugees lawfully residing in their<br />

territory. It is a valid travel document in place of a passport,<br />

however, it cannot be used to travel to the country of origin,<br />

i.e. from where the refugee fled.<br />

5.<br />

RESTRICTION OF ONWARD MOVEMENT<br />

Once refugees or asylum seekers have found a safe place and<br />

protection of a state or territory outside their territory of origin<br />

they are discouraged from leaving again and seeking protection<br />

in another country. If they do move onward into a second<br />

country of asylum this movement is also called “irregular<br />

movement” by the UNHCR. UNHCR support in the second<br />

country may be less than in the first country and they can even<br />

be returned to the first country.

Myanmar<br />

Vietnam<br />

Packistan<br />

Butan<br />

Sri Lanka<br />

China<br />

Bangladesh<br />

India<br />

Nepal<br />

Thailand<br />

Indonesia<br />

Cambodia<br />

Ukraine<br />

Croatia<br />

Bosnia<br />

Serbia<br />

Russia<br />

Colombia<br />

El Salvador<br />

Venezuela<br />

Haiti<br />

Mexico<br />

Turkey<br />

Palestine<br />

Armenia<br />

Iraq<br />

Iran<br />

DR Congo<br />

CAR<br />

Burundi<br />

Eritrea<br />

Sudan<br />

Western Sahara<br />

South Sudan<br />

Mali<br />

Nigeria<br />

Ivory Coast<br />

Mauritania<br />

Guinea<br />

Zimbabwe<br />

Egypt<br />

Ghana<br />

Somalia<br />

Ethiopia<br />

Senegal<br />

Rwanda<br />

21 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

Afghanistan*<br />

Syria*<br />

* Scaled down by a factor of 10

54<br />

PER<br />

CENT<br />

22 REFUGIUM<br />

3.2<br />

MILLION<br />

ASYLUM-SEEKERS<br />

By end 2015, about 3.2million<br />

people were waiting for a<br />

decision on their application for<br />

asylum.<br />

107,100<br />

RESETTLEMENT<br />

In 2015 UNHCR submitted<br />

134,000 refugees to States for<br />

resettlement. According to<br />

government statistics, States<br />

admitted 107,100 refugees for<br />

resettlement during the year,<br />

with or without UNHCR’s assisstance.<br />

The USA accepted the<br />

highest number - 66,500.<br />

TOP<br />

HOST<br />

201,400 2.0<br />

REFUGEES<br />

RETURNED<br />

During 2015, only 201,400 refugees<br />

returned to their countries of origin.<br />

Most returned to Afghanistan<br />

(61,400), Sudan (39,500), Somalia<br />

(32,300), or the Central African<br />

Republic (21,600).<br />

51<br />

PER CENT<br />

Children below 18 years of age<br />

constituted about half of the refugee<br />

population in 2015, up from<br />

41 per cent in 2009 and the same<br />

as in 2014.<br />

For the second consecutive year, Turkey hosted the largest number of<br />

refugees worldwide, with 2,5 million people.<br />

More than half (54%) of all refugees worldwide come from just three<br />

countries the Syrian Arab Rebuplic (4,9 million),Afghanistan (2,7 million),<br />

and Somalia (1,1million)<br />

1. TURKEY - 2.5 MILLION<br />

2. PAKISTAN - 1.6 MILLION<br />

3. LEBANON - 11 MILLION<br />

4. IRAN - 979,400<br />

5. ETHIOPIA - 736,199<br />

6. JORDAN - 664,100<br />

MILLION<br />

ASYLUM APPLICATIONS<br />

Asylum-seekers submitted a<br />

record high number of new applications<br />

for asylum or refugee status<br />

- estimated at 2 million. With<br />

441,900 asylum claims, Germany<br />

was the world’s largest recipient<br />

of new individual applications<br />

followed by the USA (172,700),<br />

Sweden (156,400), and the Russian<br />

Federation (152,500).<br />

98,400<br />

UNACCOMPANIED<br />

OR SEPARATED<br />

CHILDREN<br />

Unaccompanied or separated<br />

children in 78 countries - mainly<br />

Afghans, Eritreans, Syrians, and<br />

Somalis - lodged some 98,400<br />

asylum applications in 2015. This<br />

was the highest number on record<br />

since UNHCR started collecting<br />

such data in 2006.

A STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

within the Union. Countries like Italy and Greece as such<br />

have been left to deal with the problem as waves of<br />

refugees arrive on their shores.<br />

A disparity of ideas and lack of planning,<br />

has only aided to intensify the<br />

current problems.<br />

The astronomical rise of refugees in the past few years<br />

has been met with shortsighted planning and policy<br />

making, which has served little more than to exasperate<br />

the current problem. Following a top down approach,<br />

zero concrete solutions have filtered through these bureaucratic<br />

processes. Europe itself, the most publicized<br />

destination of the current wave of refugees has found<br />

itself at a cross roads. A United front, dealing with the<br />

problem and generating viable solutions together has<br />

been far from the actual outcomes, with many countries<br />

suddenly intensifying borders with their neighbors<br />

12.4 24<br />

86<br />

MILLION<br />

The rate at which people are forced to flee their homes<br />

is staggering, with as many as 24 people displaced per<br />

minute globally in 2015. People by and large do not<br />

want to leave their homes, families and livelihoods but<br />

are instead forced into this volatile status of becoming a<br />

refugee. Much ado is made about the migration of refugees<br />

to Europe, but one of the most important statistics<br />

that is overlooked is that 86 percent of refugees are actually<br />

hosted in developing countries. This means that<br />

countries that are more often then not, struggling to<br />

deal with existential problems within their own country<br />

are now left to deal with large influxes of people who are<br />

in desperate need for assistance and put a greater strain<br />

on the already fragile state of these places.<br />

PER CENT<br />

23 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

An estimated 12,4 million people were<br />

newly displaced due to conflict or persecution<br />

in 2015.This included 8,6 million<br />

individuals displaced within the borders<br />

of their own country and 1,8 million<br />

newly displaced refugees. The others<br />

were new applicants for the asylum.<br />

3.7<br />

MILLION<br />

UNHCR estimates that at least 10 million<br />

people globally were stateless at the end<br />

of 2015. However, data recorded by the<br />

governments and communicated to UN-<br />

HCR were limited to 3.7 million stateless<br />

individuals in 78 countries.<br />

PERSONS<br />

EVERY MINUTE<br />

On average 24 people worldwide were<br />

displaced from their homes every minute<br />

of every day during 2015 - some 34,000<br />

people per day. This compares to 30 per<br />

minute in 2014 and 6 per minute in 2005.<br />

Developing regions hosted 86% of<br />

the world’s refugees under UNHCR’s<br />

mandate. At 13,9 million people , this<br />

was the highest figure in more than two<br />

decades. The least developed countries<br />

provided asylum to 4.2 million refugees<br />

or about 26 per cent of the global total.<br />

183/1000<br />

REFUGEES/<br />

INHABITANTS<br />

Lebanon hosted the largest number<br />

of refugees in relation to its national<br />

population with 183 refugees per 1,000<br />

inhabitants. Jordan (87) and Nauru (50)<br />

ranked second and third, respectively.

Xenophobia has run rampant, fueled<br />

through negative publications from<br />

global and local news outlets, turning<br />

many local populations against the<br />

influx of refugees. This has been seen<br />

in the decision for England to vote for<br />

Brexit, with migration one of the most<br />

pressing concerns for the UK.<br />

7th<br />

UK’s rank in EU in<br />

terms of total number<br />

of asylum applications<br />

Asylum application in Europe - 2010 to 2014<br />

Top ten countries by number of asylum - seekers<br />

GERMANY<br />

FRANCE<br />

SWEDEN<br />

ITALY<br />

UK<br />

SWITZERLAND<br />

BELGIUM<br />

AUSTRIA<br />

NETHERLANDS<br />

HUNGARY<br />

0 100k 200k 300k 400k 500k<br />

24 REFUGIUM<br />

25,771<br />

Asylum application in<br />

UK up until June 2015.<br />

Asylum application in Europe - 2010 to 2014<br />

Number of asylum seekers per 1000 inhabitants<br />

SWEDEN<br />

MALTA<br />

LUXEMBOURG<br />

SWITZERLAND<br />

MONTENEGRO<br />

NORWAY<br />

41%<br />

Positive decisions on<br />

asylum applications<br />

in UK for year ending<br />

June 2015.<br />

AUSTRIA<br />

CYPRUS<br />

GERMANY<br />

UK<br />

0 5 10 15 20 25<br />

Asylum beneficiaries within the EU.<br />

Origin of nationalities seeking protection<br />

-Afghanistan 8%<br />

84,132<br />

Asylum application in<br />

UK at its peak, in 2002.<br />

Other<br />

Russia<br />

Pakistan<br />

Somalia<br />

Stateless<br />

Iran<br />

Iraq<br />

Afghanistan<br />

Eritrea<br />

Syria<br />

-Eritrea 8%<br />

-Syria 37%<br />

-Iraq 5%<br />

-Iran 4%<br />

-Stateless 4%<br />

-Somalia 3%<br />

-Pakistan 3%<br />

-Russia 2%<br />

Other 26%

In contrast Germany has publicly welcomed<br />

the influx of refugees, working to<br />

help relieve the pressure of the unrelenting<br />

flow towards Europe, promising to<br />

welcome up to 1 million refugees into<br />

their country.<br />

800k<br />

Asylum-seekers and<br />

refugees expected to<br />

arrive in Germany this<br />

year<br />

Official resettlement and other admission programmes<br />

for Syrian refugees<br />

2<br />

1<br />

11<br />

10<br />

4<br />

8<br />

9<br />

12<br />

7<br />

13<br />

6<br />

5<br />

14<br />

37,531<br />

Asylum applications in<br />

Germany in July as 93<br />

percent increase over<br />

July 2014.<br />

755k<br />

Total number of asylum<br />

applications to EU<br />

for year ending in June<br />

2015<br />

3<br />

1 Canada - 11,300 2 USA - 16,286 3 Brazil - 7,380 4 Spain - 130<br />

5 Italy - 350 6 Austria - 1500 7 Germany - 35000 8 Switzerland - 3500<br />

9 Belgium - 475 10 UK - 187 11 Ireland - 610 12 Norway - 9000<br />

13 Sweden - 2700 14 FInland - 1150<br />

Syrian refugees hosted in the Middle East<br />

LEBANON<br />

25 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

65%<br />

Increase in EU applications<br />

over previous 12<br />

months<br />

IRAQ<br />

JORDAN<br />

TURKEY<br />

EGYPT<br />

0 500000 1000000 1500000 2000000

PEOPLE IN MOTION<br />

A global look at the flows of migrants.<br />

The long journeys undertaken by these<br />

migrants lead to temporary camps along<br />

their routes, often preceding what becomes<br />

a semipermanent refugee settlement.<br />

26 REFUGIUM<br />

CAUSE AND EFFECT: The longevity of conflict allows it to be visually mapped and analyzed with regards to its affects<br />

on migration and the formation of refugee camps.<br />

- Conflict Zones - Refugee Camps - Economic Migrants - Refugees

27 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE

FORCED TO FLEE, BUT<br />

WHERE TO GO?<br />

In today’s world there are worrying misconceptions about refugee<br />

movements. As seen through the statistical analysis over 80 percent of<br />

displaced people globally are hosted within developing countries. The<br />

current fear portrayed by the media regarding the ‘floods’ of refugees<br />

towards industrialized countries in Europe are superficially inflated<br />

when looked at in contrast to the number of people internally displaced<br />

within war torn countries, or the number of displaced people<br />

seeking asylum within developing countries. It is these poorer countries<br />

that have been left to deal with an issue that they are far from<br />

capable of coping with. This is seen in stark contrast when comparing<br />

Pakistan, who host one of the worlds largest refugee populations<br />

compared to that of Germany, the industrialized country with the<br />

largest refugee population. Pakistan has an economic impact with<br />

710 refugees for each US dollar of its per capita GDP due to this influx<br />

while Germany sees an impact only of 17 refugees for each dollar of<br />

per capita GDP.<br />

28 REFUGIUM<br />

“The world is failing these people,<br />

leaving them to wait out the instability<br />

back home and put their lives on hold<br />

indefinitely.”<br />

António Guterres, 2011<br />

asylum seeker<br />

-a person who has left their home country as a<br />

political refugee and is seeking asylum in another.<br />

border<br />

/ˈbɔːdə/ -a line separating two countries, administrative<br />

divisions, or other areas.<br />

chaos<br />

/ˈkeɪɒs/ -complete disorder and confusion.<br />

convention refugee<br />

-a person who meets the refugee definition in the<br />

1951 Geneva Convention relating to the Status of<br />

Refugees.<br />

This sentiment can be seen in the two maps on the right. A strong<br />

trend is quickly evident where there is an immediate correlation<br />

between the patterns shown between ‘Countries of Asylum’ and the<br />

‘Countries of Departure’. Although Europe or North America can be<br />

seen as evident countries of asylum, the weighted volume of asylum<br />

countries are, as seen more often than not, those surrounding the<br />

country of departure itself. The movement through the country of departure<br />

to one of asylum is on of the most difficult in terms of mobility<br />

of a refugee. This has lead to the large volume of internally displaced<br />

people within who often find themselves still trapped within the confines<br />

of the very crisis that they are trying to escape.<br />

There is now a global imperative to create an equitable solution to<br />

the problem of mobility and hosting refugees. If left as is, forcibly<br />

displaced people will face further hardship and marginalization without<br />

support. A global system of parity is required so they can work,<br />

send their children to school, and have access to basic services. The<br />

situation as is can only perpetuate and fester as tensions rise between<br />

indigenous populations of developing countries and refugees all competing<br />

for and relying on the same limited services on offer.

- Country of Asylum<br />

29 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

- Country of Departure

30 REFUGIUM<br />

# OF TIMES<br />

IN TOP 20<br />

36<br />

32<br />

7<br />

15<br />

2<br />

15<br />

30<br />

8<br />

8<br />

11<br />

13<br />

9<br />

13<br />

31<br />

3<br />

9<br />

2<br />

25<br />

15<br />

3<br />

4<br />

36<br />

3<br />

12<br />

17<br />

4<br />

2<br />

14<br />

24<br />

8<br />

4<br />

12<br />

10<br />

16<br />

22<br />

15<br />

12<br />

28<br />

4<br />

3<br />

16<br />

33<br />

4<br />

1<br />

11<br />

8<br />

2<br />

35<br />

36<br />

30<br />

5<br />

1987<br />

1986<br />

1985<br />

1984<br />

1983<br />

1982<br />

1981<br />

1980<br />

1995<br />

1994<br />

1993<br />

1992<br />

1991<br />

1990<br />

1989<br />

1988<br />

1987<br />

1986<br />

1985<br />

1984<br />

1983<br />

1982<br />

1981<br />

1980<br />

2014<br />

2013<br />

2012<br />

2011<br />

2010<br />

2009<br />

2008<br />

2007<br />

2006<br />

2005<br />

2004<br />

2003<br />

2002<br />

2001<br />

2000<br />

1999<br />

1998<br />

1997<br />

1996<br />

1995<br />

1994<br />

1993<br />

1992<br />

1991<br />

1990<br />

1989<br />

1988<br />

2014<br />

2013<br />

2012<br />

2011<br />

2010<br />

2009<br />

2008<br />

2007<br />

2006<br />

2005<br />

2004<br />

2003<br />

2002<br />

2001<br />

2000<br />

1999<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

AFGHANISTAN<br />

ANGOLA<br />

ARMENIA<br />

AZERBAIJAN<br />

BHUTAN<br />

BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA<br />

BURUNDI<br />

CENTRAL AFRICAN REP.<br />

CHAD<br />

CHINA<br />

COLOMBIA<br />

CROATIA<br />

DEM. REP. OF CONGO<br />

EAST TIMOR<br />

EL SALVADOR<br />

EQUATORIAL GUINEA<br />

ERITREA<br />

ETHIOPIA<br />

GUATEMALA<br />

IRAN<br />

IRAQ<br />

IVORY COAST<br />

LAOS<br />

LIBERIA<br />

MALI<br />

MAURITANIA<br />

MOZAMBIQUE<br />

MYANMAR<br />

NAMIBIA<br />

NICARAGUA<br />

PAKISTAN<br />

PHILIPPINES<br />

RUSSIA<br />

RWANDA<br />

SERBIA<br />

SIERRA LEONE<br />

SOMALIA<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

2015<br />

SOUTH SUDAN<br />

CAMBODIA<br />

SRI LANKA<br />

SUDAN<br />

SYRIA<br />

TOGO<br />

TURKEY<br />

UGANDA<br />

UKRAINE<br />

UNKNOWN ORIGIN<br />

VIETNAM<br />

WESTERN SAHARA<br />

YEMEN<br />

EXPORTING FEFUGEES<br />

RANK 1 RANK 2-5 RANK 6-10 RANK 11-20<br />

2015<br />

IMPORT/EXPORT<br />

Refugees from South Sudan increased<br />

more than fivefold- from 114.500 in<br />

2013 to 616.200 in 2014-due to the<br />

outbreak of civil war.<br />

The movement of refugees between countries is likened<br />

to that of imports and exports of goods. The staggering<br />

numbers of people moving between countries is in a<br />

constant state of flux, with countries who formerly were<br />

a major source of refugees finding their roles inverted.<br />

This can be seen in examples such as Ethiopia, once<br />

a major source of refugees, who now find themselves<br />

Syria was the top origin country in<br />

2015 with 4.5 milions refugees.<br />

An additional 7.6 milion Syrians- or<br />

as sub-Saharan Africa’s largest host country. Most new<br />

40 percent of the population- are<br />

internally displaced<br />

arrivals are from neighboring countries such as South<br />

Sudan and Eritrea. In 2015 Turkey topped the host rankings<br />

for the first time in 3 decades, where as previously<br />

the position had been perennially held by either Iran or<br />

Pakistan

1981<br />

1980<br />

AFGHANISTAN<br />

ALGERIA<br />

ANGOLA<br />

ARMENIA<br />

AUSTRALIA<br />

AZERBAIJAN<br />

BANGLADESH<br />

BURUNDI<br />

CAMEROON<br />

CANADA<br />

CHAD<br />

CHINA<br />

CONGO<br />

COSTA RICA<br />

CROATIA<br />

DEM. REP. OF CONGO<br />

EQUADOR<br />

EGYPT<br />

ETHIOPIA<br />

FRANCE<br />

GERMANY<br />

GUATEMALA<br />

GUINEA<br />

HONDURAS<br />

INDIA<br />

INDONESIA<br />

IRAN<br />

IRAQ<br />

IVORY COAST<br />

JORDAN<br />

KENYA<br />

LEBANON<br />

MALAWI<br />

MALAYSIA<br />

MEXICO<br />

NEPAL<br />

NETHERLANDS<br />

NIGERIA<br />

PAKISTAN<br />

RUSSIA<br />

RWANDA<br />

SAUDI ARABIA<br />

SERBIA<br />

SOMALIA<br />

SOUTH SUDAN<br />

SUDAN<br />

SWEDEN<br />

SYRIA<br />

TANZANIA<br />

THAILAND<br />

TURKEY<br />

UGANDA<br />

UNITED KINGDOM<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

VENEZUELA<br />

YEMEN<br />

ZAMBIA<br />

ZIMBABWE<br />

1983<br />

1982<br />

1981<br />

1980<br />

2013<br />

2012<br />

2011<br />

2010<br />

2009<br />

2008<br />

2007<br />

2006<br />

2005<br />

2004<br />

2003<br />

2002<br />

2001<br />

2000<br />

1999<br />

1998<br />

1997<br />

1996<br />

1995<br />

1994<br />

1993<br />

1992<br />

1991<br />

1990<br />

1989<br />

1988<br />

1987<br />

1986<br />

1985<br />

1984<br />

1983<br />

1982<br />

2001<br />

2000<br />

1999<br />

1998<br />

1997<br />

1996<br />

1995<br />

1994<br />

1993<br />

1992<br />

1991<br />

1990<br />

1989<br />

1988<br />

1987<br />

1986<br />

1985<br />

1984<br />

2015<br />

2014<br />

2013<br />

2012<br />

2011<br />

2010<br />

2009<br />

2008<br />

2007<br />

2006<br />

2005<br />

2004<br />

2003<br />

2002<br />

2015<br />

2014<br />

# OF TIMES<br />

IN TOP 20<br />

1<br />

20<br />

1<br />

14<br />

4<br />

7<br />

7<br />

15<br />

4<br />

15<br />

13<br />

36<br />

1<br />

3<br />

3<br />

32<br />

1<br />

2<br />

25<br />

24<br />

35<br />

5<br />

14<br />

3<br />

24<br />

1<br />

36<br />

4<br />

8<br />

10<br />

24<br />

3<br />

7<br />

6<br />

12<br />

2<br />

4<br />

1<br />

36<br />

4<br />

1<br />

12<br />

13<br />

11<br />

4<br />

34<br />

11<br />

7<br />

29<br />

9<br />

4<br />

30<br />

18<br />

36<br />

7<br />

8<br />

13<br />

4<br />

31 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

IMPORTING FEFUGEES<br />

RANK 1 RANK 2-5 RANK 6-10 RANK 11-20<br />

Ethiopia, once a major source of refugees<br />

as citizens fled its 1974-1991 civil<br />

war, is now sud-Saharian Africa’s largest<br />

host country. Most new arrivals are<br />

from South Sudan and Eritrea.<br />

Turkey topped the host rankings in<br />

2015 more than 1.8 milion<br />

Syrian refugees within its borders. For<br />

three decades prior, either Iran or Pakistan<br />

had held the peak spot.

ITS A GLOBAL REFUGEE CRISIS -<br />

THE MAJOR EFFECTED REGIONS<br />

“A crisis is never really a crisis until it<br />

is your own.”<br />

BALKANS -<br />

32 REFUGIUM<br />

The Balkans have become a passageway. Countries<br />

such as Serbia and Macedonia have become inundated<br />

with refugees, with 7000 and 400000 people moving<br />

through these two areas in less than two months<br />

respectively. [United Nations] The origin of the refugees<br />

are many, stemming from areas such as Afghanistan,<br />

Syria and Kosovo. The Balkans have become a major<br />

stopping point for refugees trying to enter Western<br />

Europe. The high influx of migrants though has caused<br />

a bottle neck effect in the region. With many European<br />

countries closing their borders such as Hungary and<br />

Austria, the flood of refugees is abruptly halted, and<br />

what was once seen as a passageway has now developed<br />

into a series of ‘temporary’ refugee camps in both<br />

border towns and capital cities such as Belgrade.<br />

MIDDLE EAST -<br />

When a refugee crisis erupts it is almost always that the<br />

neighboring countries of the region bear the brunt of the<br />

initial ingress. This can be enormously taxing. Especially<br />

onto countries which may not be in much better condition<br />

themselves, or lack the capacity to deal with such<br />

a large influx of troubled persons. This couldn’t ring<br />

truer for the Middle East, where years of war and fighting<br />

from countries such as Iraq and now Syria have taken a<br />

toll on neighboring countries. Jordan’s unemployment<br />

rates have doubled while refugees now make up over 20<br />

percent of Lebanon’s current population. This has had<br />

a knock on effect, with countries such as Turkey entirely<br />

shutting its border with Syria. This often has disastrous<br />

effects for migrants seeking refuge, turning them back

SOUTH EAST ASIA -<br />

Much is made of the terrible crossing of the Mediterranean<br />

sea, but the little publicized escape of the Rohingya<br />

people from Bangladesh and Myanmar to places like<br />

Malaysia and Indonesia are just as tragic. After being<br />

denied basic human rights, the Rohingya people have<br />

been forced to flee, but many of them have been stuck<br />

at sea for large periods of time as host countries have<br />

barred or turned back smugglers boats.<br />

MEDITERRANEAN SEA -<br />

The largest of the current crisis and the most widely<br />

publicized is that of the crossings of Mediterranean to<br />

reach Europe. War raging all across North Africa, and<br />

the proximity of the ‘promised land’ of Europe, where<br />

Italy and Greece have become the landing points, are<br />

the only hope and salvation for many refugees. The<br />

huge influx of over 150000 people trying to gain access<br />

to Europe this way has had devastation repercussions<br />

with over 2000 people dying at sea. Poverty in countries<br />

neighboring problem states make them unfit destinations<br />

for migrants, while other perils are rife within this<br />

journey as human trafficking has become a multi million<br />

dollar industry.<br />

33 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

EASTERN EUROPE -<br />

Ravaged by civil war, Ukraine has become a hotbed of<br />

conflict recently. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians<br />

have been forced to flee conflict. Europe is statistically<br />

the favored choice for refugees, but many states such<br />

as Italy, Poland and Germany have declined asylum<br />

applications as they are already inundated with other<br />

refugees from around the world. Thus Russia has been<br />

forced to take on the refugees from this crisis. This catastrophe<br />

has had huge economic repercussions on the<br />

region and not nearly enough funds have been raised<br />

from the United Nations in order to help to address the<br />

refugee crisis financially.

TELLING BOTH SIDES OF<br />

THE STORY<br />

How crisis becomes a tool<br />

for media manipulation<br />

It can be seen without a doubt the the media today influences our<br />

opinions. Technological advancements continue to enhance and<br />

evolve media outlets, and these constant changes and availability<br />

of new media platforms means that the speed at which news travels<br />

around the world is unprecedented. The majority of populations who<br />

have access to any type of news and information can easily be swayed<br />

by attention grabbing headlines. As a result of this, people tend to be<br />

easily influenced by these representations. Therefore, the media can<br />

greatly influence our opinions with an acute immediacy and it plays<br />

an ever-increasing role in shaping governmental policymaking.<br />

34 REFUGIUM<br />

An example of this is how the current refugee crisis has triggered many<br />

debates surrounding the reactions of governmental agencies from<br />

various countries and what they can do in order to help the masses<br />

of people desperately seeking safety. This crisis is a perfect example<br />

of how easily public opinions can be shaped and influenced by the<br />

media. Society today only knows what they are told through the various<br />

media sources, and if something is not represented as important<br />

in the media then it is soon forgotten about. In this case one can see<br />

instances where some newspaper headlines rapidly change from one<br />

extreme to another, first headlines demanding to “send in the army”<br />

and then to “welcome with open arms”. Even subtle differences in<br />

phrasing of “migrant” and “refugee” are constantly used interchangeably,<br />

despite having completely different definitions. This does not<br />

stop the public hanging on every word that the media provided them<br />

with, we only know what is communicated to us through the media.<br />

This just goes to show how much of a powerful weapon the media and<br />

how it chooses to portray topics really is. This can be seen in an example<br />

such as the shocking image of the washed up body of three-year<br />

old Aylan Kurdi, which led many people to express great disgust at the<br />

perceived lack of effort of some governments, regardless of whether<br />

they actually are assisting refugees or not. Even though this image has<br />

been widely circulated around the globe and has caused much public<br />

outcry, many people accused the newspaper of deliberately distorting<br />

facts in order to ‘morally blackmail the public’. Either way, it still shows<br />

the influence the media has over the information we know.<br />

crisis<br />

/ˈkrʌɪsɪs/ -a time of intense difficulty or danger.<br />

deterioration<br />

/dɪˌtɪərɪəˈreɪʃn/ -the process of becoming progressively<br />

worse.<br />

The media has both positive and negative influences. It can help<br />

make a person more aware of what is happening on a local, national<br />

and global level, or it can warp one’s perspective of the truth. We only<br />

know the information that is given to us, and depending on how that<br />

information is portrayed society will form certain ideas. The media has<br />

the ability to control the topics we discuss in daily life, and once something<br />

is out of sight - within the media - it is out of mind and we move<br />

on to the next topic implanted into our information resources.<br />

displace<br />

/dɪsˈpleɪs/ -force (someone) to leave their home,<br />

typically because of war, persecution, or natural<br />

disaster.

Walking a thin line<br />

‘I<br />

don’t think<br />

there is an<br />

answer<br />

that can<br />

be<br />

achieved simply b<br />

y<br />

taking more and more r<br />

efugees.<br />

This is a disgrace. That we are<br />

letting people die and seeing dead bodies<br />

on the beaches, when together, Europe is<br />

such a wealthy place. We should be able<br />

to fashion a response.<br />

We<br />

simply must<br />

find a durable<br />

resettlement<br />

solution. A<br />

failure to do<br />

so will<br />

result in<br />

tremendous<br />

harm being done to this group<br />

of men, women and children.<br />

The EU<br />

owe me<br />

$3bn!!!<br />

If the EU<br />

does not grant<br />

visa liberalization<br />

for Turkish citizens,<br />

Ankara will no<br />

longer respect the<br />

March agreement<br />

on migrants. The<br />

EU governments are<br />

not honest. Turkey still<br />

hosts three million people.<br />

Talking a thin line<br />

35 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

I<br />

will build a<br />

great<br />

wall -- and<br />

nobody builds walls<br />

better t han me, believe<br />

me<br />

--and I'll build<br />

them very<br />

inexpensively.<br />

I will build a great, great<br />

wall on our southern border, and I<br />

will make Mexico pay for that wall. Mark<br />

my words.<br />

It<br />

is vital that<br />

Europe<br />

welcomes asylum<br />

seekers with<br />

dignity. We will<br />

however<br />

though send<br />

back to their countries<br />

those who do not need help. Refugees<br />

are victims of the same terrorist system.<br />

If<br />

Europe fails<br />

on the question of<br />

refugees, then it<br />

won’t be the Europe<br />

we wished for,<br />

Europe as a<br />

whole needs to<br />

move. Germany is a<br />

strong country, the motivation<br />

with which we should approach<br />

these things has to be: We have<br />

handled so much. We can handle it!<br />

Hungary is<br />

under<br />

enormous<br />

pressure,<br />

whether or not<br />

the EU will<br />

succeed in pushing a<br />

new EU asylum and migrant<br />

system down the throats of the central<br />

European countries, including ours.<br />

The EU wants us all to remain puppets.<br />

Solving<br />

the humanitarian<br />

prob-l ems in Syria<br />

necessitates not only<br />

emergency aid, but also<br />

needs to eliminate their<br />

root cause. China has paid<br />

close attention to the<br />

refugee issue in Europe and<br />

the Mediterranean and sympathizes<br />

with the refugees.The Chinese<br />

government will further provide<br />

assistance to refugees in relevant

36 REFUGIUM

PAST/ PRESENT/<br />

FUTURE<br />

Statistically we have already shown<br />

that we are in one of the worst<br />

moments in human history with<br />

regards to a global humanitarian<br />

crisis. There are 60 million displaced<br />

people in the world, another stateless<br />

child is born every 10 minutes,<br />

and three million people have no<br />

access to water, food, housing,<br />

work, education, and are caught in<br />

legal limbo.<br />

...This is nothing new though...<br />

We have been here before. A spectacular<br />

global opera of deja vu has<br />

gripped up as all, yet as designers<br />

we are often some of the most guilty<br />

in failing to recognize this. Failing to<br />

learn from events of such magnitude<br />

from the past, has lead us to<br />

little more than beautifying on the<br />

surface what is a more fundamental<br />

problem. The rise of the “Designer<br />

Refugee Camp” is a superfluous<br />

gimmick providing ‘temporary shelter’<br />

to a problem that is far more<br />

permanent. Austerity runs rife, as<br />

governments push for barren, frugal<br />

attempts at refugee camps to deter<br />

future asylum seekers. This all goes<br />

on while global spending runs rampant<br />

on global positioning systems<br />

to monitor refugee movement or<br />

creating weapons to bomb the very<br />

countries afresh from where the<br />

refugees originate.<br />

37 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

We have ultimately failed at papering<br />

over the cracks of this crisis, and<br />

looking at what the future holds, the<br />

walls are about to come tumbling<br />

down.

38 REFUGIUM

PAST

HISTORY OF AN EVER EXISTING<br />

PROBLEM<br />

1940 - 2000<br />

As the single largest migration of refugees to Europe<br />

since WWII, the scale of the current crisis is without<br />

question. There have been many other events historically<br />

leading up to this which have not garnered the same<br />

exposure. The precedent set of such historic moments<br />

is invaluable in terms of understanding and finding a viable<br />

solution to dealing with our current problems. The<br />

following is a brief summary of these major events.<br />

1940 to 1960<br />

Post-World War II<br />

With 9 major events occurring during this period, 81.6<br />

million were displaced.<br />

The 1950s and 60’s were dominated with events culminating<br />

in Asia and Africa. The partition of India and<br />

Pakistan in 1947 was the first of these events, resulting<br />

in 14 million people displaced from the Indian subcontinent.<br />

Africa was the melting pot of multiple wars of<br />

independence that were prevalent within central Africa<br />

during this time. Countries such as the Congo, Nigeria,<br />

Angola and Algeria were some of the hardest hit. The<br />

Algerian war of Independence was responsible for at<br />

least 1.2 million people displaced, where as the Biafran<br />

war in Nigeria displaced 2 million people. Xenophobia<br />

uprooted many ethnic communities even long after the<br />

wars had passed through these regions.<br />

1960 to 2000<br />

Post-World War II<br />

With 32 major events occurring during this period,<br />

46.5 million were displaced.<br />

40 REFUGIUM<br />

Looking at the adjacent graph it is quick to see that WWII<br />

was responsible for the largest displacement of people<br />

in recent history. Ethnic Germans were expelled from the<br />

Soviet Union, while millions of others fled to escape the<br />

brutal rule of Joseph Stalin. Millions more were greatly<br />

affected by the events of the Holocaust. The UNHCR was<br />

established by Allied forces after the war, in 1950, in order<br />

to provide aid for the current and all future refugees<br />

and people fleeing conflict.<br />

The single largest event during this period was undoubtedly<br />

the Bangladesh war of Independence. 10 million<br />

Bengalis, mostly of Hindu faith, had to escape the<br />

violence of mass killings, rape, looting and arson. This<br />

led to the vast migration of refugees from East Bengal<br />

to India. Concurrently to this, the Vietnam war was to be<br />

another major catalyst for refugee migration with over<br />

2.7 million Vietnamese fighters migrating from the South<br />

to the North of Vietnam between 1965 and 1972.<br />

Ten largest refugee crisis events throughout history.

0<br />

100000<br />

200000<br />

300000<br />

400000<br />

500000<br />

600000<br />

700000<br />

800000<br />

900000<br />

1000000<br />

2000000<br />

3000000<br />

4000000<br />

5000000<br />

8000000<br />

11000000<br />

14000000<br />

17000000<br />

20000000<br />

30000000<br />

40000000<br />

Soviet Invasion of<br />

Afghanistan<br />

WWII<br />

Rhodesian<br />

Rebellion<br />

Partition of Pakistan<br />

and India<br />

Invasion of<br />

Ethiopia<br />

Establishment of<br />

Jewish State<br />

Invasion of<br />

Eritrea<br />

Post WWII<br />

(Russia/Ukraine/Belarus)<br />

Cambodian Civil War<br />

Post WWII<br />

(Germany/USSR/Poland)<br />

Iran-Iraq War<br />

Post WWII<br />

(European Nations)<br />

Civil Wars in Central<br />

America<br />

Chinese Cultural<br />

Revolution<br />

Nagorno - Karabakh<br />

North Vietnam<br />

Formation of Communism<br />

Iraqi Suppression of<br />

Rebels<br />

Hungarian Uprising<br />

Ethnic Cleansing<br />

Croatia<br />

Algerian War of<br />

Independence<br />

Chechnya declares<br />

Independence<br />

41 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

Hutu coup d’etat<br />

Civil war in<br />

Mozambique<br />

Arab Israeli War<br />

Burmese<br />

Expulsion<br />

Biafran War<br />

Civil War in<br />

Tajikistan<br />

Bangladesh War of<br />

Independence<br />

Secessionist fighting<br />

in Georgia<br />

Vietnam War<br />

Rwandan<br />

Genocide<br />

Uganda Expulsion<br />

Order<br />

Russian Suppression of<br />

Chechnya<br />

Laotian Civil war<br />

Fall of Yugoslavia<br />

Burmese<br />

Expulsion<br />

Vietnam War<br />

NATO Air-strikes in<br />

Serbia

42 REFUGIUM<br />

The Cold War and its resulting proxy wars were the<br />

largest talking point of this era, but by no means the<br />

only determinate cause of refugees. Millions of people<br />

were displaced in the middle east from countries such<br />

as Afghanistan. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in<br />

1979 caused 6.3million refugees alone, many of them<br />

migrating to neighboring Iran and Pakistan. North Africa<br />

was effected through Soviet Invasion as well and consequently<br />

the Ogaden war broke out, displacing over 1<br />

million people. The Cold War also had a knock on effect<br />

in many Eastern European countries. As the power of<br />

the former Soviet Union started to wane, ethnic and<br />

nationalist communities within the former Eastern Bloc<br />

began to catalyze. The mass movement of people started,<br />

with migration between Armenia and Azerbaijan as<br />

well as within Georgia and Tajikistan.<br />

“Berlin is the testicles of the<br />

West, every time I want the<br />

West to scream, I squeeze on<br />

Berlin.”<br />

Nikita Khrushchev, 1962<br />

Central America, specifically the areas of Nicaragua,<br />

El Salvador and Guatemala were rife with Civil War<br />

between 1981 and 1989, seeing more than 2 million<br />

people being displaced to countries such as Belize,<br />

Costa Rica and Mexico.<br />

displaced.<br />

1940 TO 2000<br />

ENVIRONMENTAL REFUGEES<br />

Looking at the 8 major events occurring during this<br />

period, 81.6 million were effected.<br />

The Earth’s climate is changing at a rate that has exceeded<br />

most scientific forecasts. Some families and communities<br />

have already started to suffer from disasters and<br />

the consequences of climate change, forced to leave<br />

their homes in search of a new beginning.<br />

Natural disasters are often difficult to predict and even<br />

when predicted there is very little one can do to escape<br />

the devastation which they can bring. Environmental<br />

refugees draw a different kind of problem, as unlike<br />

wars, the duration of the event is often very brief but the<br />

impact of the disaster itself can be felt for generations to<br />

come. The Yangtze River Flood in China is an ideal example<br />

of this. The flood itself came after 3 years of exhaustive<br />

famine in the area, after which a month of torrential<br />

rain killed 4 million people furthermore effecting 51<br />

million people by destroying the rice crops and creating<br />

famine and disease which ultimately killed even larger<br />

numbers of the population.<br />

The early 1990s were an extremely turbulent period<br />

globally in terms of refugees. Europe was awash with<br />

conflict in the early 90’s. The fighting between Armenia<br />

and Azerbaijan, the Croatian War of Independence and<br />

the Civil War in Tajikistan created 2 million refugees<br />

alone. Simultaneously Asia was a hotbed of confrontation<br />

within the 90’s. The Iraqi oppression of rebel movement<br />

displaced 1.82 million people while the events of<br />

the expulsion of people from Burma along with the end<br />

of the Vietnam war created another million refugees.<br />

Africa underwent the largest of its refugee crisis at this<br />

time. The 16 year civil war in Mozambique creating 5.7<br />

million refugees while in 1994 one of the darkest stains<br />

in African history, the Rwandan genocide displaced 3.5<br />

million people. One of the final events of the 1990’s was<br />

that of the Kosovo war, where after the NATO bombing,<br />

over 1 million people, both Serbian and Albanian were<br />

Betti Malek—pictured on May 17, 1945—was one of numerous child<br />

refugees brought from Belgium to England after the Germans seized<br />

Antwerp in 1940.

0<br />

100000<br />

200000<br />

300000<br />

400000<br />

500000<br />

600000<br />

700000<br />

800000<br />

900000<br />

1000000<br />

2000000<br />

3000000<br />

4000000<br />

5000000<br />

8000000<br />

11000000<br />

14000000<br />

17000000<br />

20000000<br />

30000000<br />

40000000<br />

Indian Ocean<br />

Tsunami (2004)<br />

Yellow River<br />

Flood (1938)<br />

Bhola Cyclone<br />

(1970)<br />

Haiti Earthquake<br />

(2010)<br />

Typhoon Nina<br />

(1975)<br />

Tangshan<br />

Earthquake (1976)<br />

Haiyuan<br />

Earthquake (1920)<br />

China Floods<br />

Great Kanto<br />

Earthquake<br />

REPETITION: Certain nations have had more misfortune than others. Below we examine how these refugee disasters<br />

both man made and natural occur with varying frequency on continental and national levels.<br />

6<br />

- CHINA<br />

43 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

3<br />

- RUSSIA<br />

2<br />

- VIETNAM<br />

- IRAQ<br />

- RWANDA<br />

- BANGLADESH<br />

- BURMA<br />

Asia Europe Africa South America<br />

Asia Africa South Americ

44 REFUGIUM

FUTURE

Radicilization of Political Systems<br />

Intelligent Buildin<br />

2056<br />

Revolutionised Urban Landscap<br />

2052<br />

New world orders are formed<br />

Collapse of Free Market Capitalism<br />

2050<br />

Half the World is ‘Bankrupt’<br />

60 percent of the Amazon lost<br />

2053<br />

Deforestation of 2.7 million sq km.<br />

Fish Body Size Decrease<br />

Changes in distribution and abundance<br />

2055<br />

Wine Industry Falters<br />

Geoengineering Introduced<br />

46 REFUGIUM<br />

2054<br />

THE FUTURE IS<br />

NOT SO BRIGHT:<br />

The Refugee crisis is not something that is<br />

inherently new to us as a problem, as it has plagued<br />

humanity within different epochs of history. The future of<br />

the issue is something that is not self healing either. In fact the future<br />

looks extremely bleak, as the number of refugees, mostly predicted as environmental<br />

refugees, is expected to skyrocket 10 fold within the next 50 years. If serious<br />

thought is not put into the solution of this problem and strategies are not put into place on a<br />

global level, then the future of humanity certainly is in jeopardy. Policies of borders need to challenged,<br />

along with the way we handle refugees, as well as city and place making within our current urban fabric.

gs<br />

es<br />

Water DIversion Project<br />

2057<br />

China diverts main water supply<br />

Global Temperature<br />

2065<br />

1.2m Rise Sea Levels<br />

Advertising Changes<br />

2061<br />

Personal Transport<br />

Media fragmented/diversified<br />

Colonization of Mars<br />

2056<br />

2066<br />

Permanent Human Presence<br />

Smaller, safer, Hi-Tech<br />

Global Population<br />

2064<br />

Interstellar Message<br />

2059<br />

Message arrives at Gliese 777<br />

Solar Supergrids<br />

2058<br />

Renewable Energy<br />

Global Monsoons<br />

2060<br />

Population is reaching a plateau<br />

Rainfall intensity has increased by 20%<br />

47 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

End of Oil Era<br />

Designer Babies<br />

2062<br />

2063<br />

Major GLobal Slowdown<br />

Advances in Genetic Engineering

48 REFUGIUM<br />

FUTURE OF AN EVER EVOLVING<br />

PROBLEM<br />

2050 - 3050<br />

As a global society we have already been shown to be<br />

far out of our depth with dealing with the current refugee<br />

crisis. The current population of refugees though<br />

pales in comparison to what is predicted for the future<br />

of this dilemma. 60 million globally displaced people<br />

are expected to swell to as many as 250 million by 2050<br />

based on the exponential rate at which these numbers<br />

have progressed over the past few years, compounded<br />

by the ever present problems provided by global warming,<br />

contributing to the production of environmental<br />

refugees.<br />

Taking a hypothetical look at the future, based on data<br />

that supports the plausibility of such events, a hypothetical<br />

summary of some of the major crisis which<br />

could come into play is provided.<br />

2050<br />

NUCLEAR TERRORISM<br />

WASHINGTON<br />

Radical Islam and its resentment of the West continue to<br />

produce new Jihadists. In addition, underground groups<br />

ranging from those angry at the first world’s neglect, to<br />

anarcho-primitivists, have sprung up. By 2050, at least<br />

one terrorist nuclear attack on a major world city has<br />

been conducted by one of these groups. Large amounts<br />

of nuclear material had been missing from Russia since<br />

the 1990s and some inevitably fell into the wrong hands.<br />

Being orders of magnitude greater than 9/11, the effects<br />

of this attack leave a deep psychological scar on many<br />

people alive today.<br />

2050 -2060<br />

FISHING CRISIS<br />

GLOBAL<br />

By far the greatest impact from global warming has<br />

been in the seas and oceans, where changes in heat<br />

content, oxygen levels and other biogeochemical properties<br />

have devastated marine ecosystems. Globally, the<br />

average body size of fish has declined by up to 24 per<br />

cent compared with 2000. About half of this shrinkage<br />

has come from changes in distribution and abundance,<br />

the remainder from changes in physiology. The tropics<br />

have been the worst affected regions. The plentifulness<br />

of global fish stock are a thing of the past with many<br />

species already extinct and many others now protected.<br />

The 17% of the global population that relied on fish as<br />

their primary source of sustanance have been greatly<br />

effected.<br />

2056<br />

HURRICANE KATE<br />

MEDITERRANEAN<br />

In Europe, food riots have continued to spread. Temperatures<br />

that were previously found only in North Africa<br />

and the Middle East have become the norm in central<br />

and southern parts of the continent. Britain now has a<br />

Mediterranean climate and is engaged in a food-sharing<br />

process with its neighbour Ireland. Rising sea levels, erosion<br />

and storm surges are wreaking havoc on the coastline.<br />

The first hurricane to hit the mediterranean region<br />

as a result of this climate change devastates coastal<br />

villages creating nearly 1 million European refugees.<br />

2060 -2100<br />

WATER WARS<br />

NORTH AFRICA<br />

Rapid population growth and industrial expansion<br />

is having a major impact on food, water and energy<br />

supplies. During the early 2000s, there were six billion<br />

people on Earth. By 2030, there are an additional two<br />

billion, most of them from poor countries. Humanity’s<br />

footprint is such that it now requires the equivalent of<br />

two whole Earths to sustain itself in the long term. Farmland,<br />

fresh water and natural resources are becoming<br />

scarcer by the day. However, this exponential progress<br />

was dwarfed by the sheer volume of water required by<br />

an ever-expanding global economy, which now included<br />

the burgeoning middle classes of China and India. The<br />

world was adding an extra 80 million people each year<br />

– equivalent to the entire population of Germany. By<br />

2017, Yemen was in a state of emergency, with its capital<br />

almost entirely depleted of groundwater. Significant<br />

regional instability began to affect the Middle East,<br />

North Africa and South Asia, as water resources became<br />

weapons of war.

0<br />

100000<br />

200000<br />

300000<br />

400000<br />

500000<br />

600000<br />

700000<br />

800000<br />

900000<br />

1000000<br />

2000000<br />

3000000<br />

4000000<br />

5000000<br />

8000000<br />

11000000<br />

14000000<br />

17000000<br />

20000000<br />

30000000<br />

40000000<br />

Nuclear Terrorism<br />

(Washington)<br />

Fishing Crisis<br />

Hurricane Kate<br />

(Mediterranean)<br />

Rising Sea Level<br />

(Global)<br />

War on Water<br />

(North Africa)<br />

Tibetan Uprising<br />

Fukoshima<br />

Tsunami<br />

Persectution of<br />

Whites (South Africa)<br />

Holland Deluge<br />

49 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

DELUGE: Rising sea levels as a result of the polar ice caps melting due to global warming is an ever present threat. A<br />

large portion of the world coastal cities would be lost to such a cataclysmic event, displacing unforeseen amounts of<br />

people. Environmental refugees will be by and large one of the greatest disasters of the future humankind.

Amid this turmoil, even greater advances were being<br />

made in desalination. It was acknowledged that present<br />

trends in capacity – though impressive compared to earlier<br />

decades – were insufficient to satisfy global demand<br />

and therefore a major, fundamental breakthrough would<br />

be needed on a large scale.<br />

2063<br />

TIBETAN UPRISING<br />

TIBET<br />

In light of the unfolding crisis in Europe, this constitutes<br />

a significant shift in power and resources, which<br />

inevitably results in friction with the other superpowers.<br />

One side effect of this, however, is the increasing<br />

flow of immigrants and refugees attracted by Russia’s<br />

new-found abundance and wealth. Many are fleeing<br />

resource conflicts throughout Eurasia. Due to its sheer<br />

size, it is virtually impossible for Russia to fully close its<br />

borders. This is a particular issue with those fleeing the<br />

drought-stricken Tibetan Plateau of Western China, who<br />

after a failed uprising against China itself has been left<br />

decimated in terms of infrastructure and public services.<br />

NEW STRATEGIES ARE NEEDED<br />

GLOBALLY<br />

In light of some of the catastrophes that mankind will<br />

undoubtedly face going forward, it is a lack of preparation<br />

and collaboration into how we deal with such<br />

events that leads to such devastating consequences,<br />

which often go on for many years after the catalytic<br />

event has already past. This strange thinking can be<br />

found in mans readiness for an event that potentially<br />

could not happen, with an extensive evacuation plan in<br />

place for the slopes and hill towns of Mount Vesuvius by<br />

the Italian government, which has full contingency plans<br />

in place already for such an event. This compared to the<br />

monsoons in South East Asia, which generate refugees<br />

on an annual basis in the region, yet the maximum level<br />

of planning that is done to help support this polemic is<br />

to open public buildings such as schools as makeshift<br />

shelters. It is within these contrasting approaches a major<br />

flaw can be seen. The crisis of refugees has not been<br />

approached from a planning perspective, further than<br />

laws and legislature that often exasperate the situation<br />

rather than help to mitigate the problem.<br />

The people of Bangladesh are no strangers to drastically changing<br />

climates. This annual deteriorating condition has become a quasi way of<br />

life for many of the countries rural populations.

VOLCANO<br />

STORMS<br />

TSUNAMI<br />

DROUGHT<br />

51 STATISTICAL NIGHTMARE<br />

FAMINE<br />

TOXIC<br />

EARTHQUAKES<br />

REFUGEES<br />

CATALYST: Global potentiality for disaster is constantly rising. Analysis of impending and current environmental<br />

threats highlights the areas most likely to have future refugee crisis.

52 REFUGIUM

53 REFUGIUM<br />

02<br />

DANGEROUS JOURNEY<br />

This section is dedicated to the analysis of data, experiences<br />

and interviews of refugees during their Journey.<br />

The aim is better understanding the problematics of the journey<br />

itself, isolated from both starting and end point.

THIS IS ALL<br />

MONEY I’VE<br />

GOT. WHAT IS<br />

THE PLAN?<br />

I HAVE TO<br />

LEAVE OR I<br />

WILL DIE.<br />

WE ARE<br />

LEAVING<br />

TOMORROW.<br />

DON’T ASK<br />

QUESTIONS.<br />

THIS IS ULI. HE IS TRAPPED IN HIS<br />

WAR TORN HOME COUNTRY.<br />

THE SMUG-<br />

GLERS PUT<br />

ULRICH IN<br />

THE TRUCK<br />

WITH OTHER<br />

REFUGEES AND<br />

DROVE OFF.<br />

THE PEOPLE<br />

WERE TRAPPED<br />

WITH NO<br />

POSSIBILITY<br />

TO LEAVE.<br />

WHY DID THEY<br />

HAVE TO TIE<br />

OUR HANDS?<br />

SOMETHING<br />

IS TERRIBLY<br />

WRONG HERE!<br />

54 REFUGIUM<br />

THE SMUGGLERS TOOK THE HOSTAGES TO A LONELY HOUSE<br />

WHERE THEY ASKED FOR MORE MONEY AND CALLED THE<br />

FAMILIES FOR RANSOM.<br />

THOSE WHO DID<br />

NOT PAY WILL<br />

DIE. THERE IS<br />

NO SPACE ON<br />

THE BOAT.<br />

WE ARE GO-<br />

ING TO SINK!<br />

HELP!<br />

I FELL OFF!<br />

HELP!<br />

PLEASE HOLD<br />