The Creative Process: The Arts of War (Spring 2017)

The Creative Process is The Mumbai Art Collective's flagship magazine.

The Creative Process is The Mumbai Art Collective's flagship magazine.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

Masthead & Publisher Information<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mumbai Art Collective<br />

E: info@themumbaiartcollective.com<br />

W: themumbaiartcollective.com<br />

: +91 80801 85000<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong> is <strong>The</strong> Mumbai Art Collective’s flagship<br />

magazine, that aims to look at art critically and analytically, and the<br />

creative processes that converge in the creative <strong>of</strong> the art.<br />

Read <strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong> online at thecreativeprocess.co.in.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mumbai Art Collective is an arts organisation that was born<br />

out <strong>of</strong> a desire to understand the thought process behind the creation<br />

<strong>of</strong> art. <strong>The</strong> Mumbai Art Collective jumps right into the innermonologues<br />

<strong>of</strong> the creator to understand and document the<br />

explorations and ruminations behind creative activity. Paintings<br />

displayed in galleries are only the undertones <strong>of</strong> the real picture,<br />

which can only be truly understood by understanding the artist and<br />

the artist’s mind. Learn more on our website,<br />

themumbaiartcollective.com, and via our Facebook page,<br />

facebook.com/themumbaiartcollective.<br />

1

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Mumbai Art Collective Team<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Founder & Head Curator: Ishaan Jajodia<br />

<strong>Creative</strong> Head: Kabeer Khurana<br />

Head <strong>of</strong> Operations: Tanay Punjabi<br />

Sanya Thakrar<br />

Head <strong>of</strong> PR: Sharmishta Muralidharan<br />

Yashvi Gada<br />

Poet-in-Residence: Tamarind Fall<br />

Aanchal Dusija<br />

Arjun Shukla<br />

Gauri Saxena<br />

Hasri Hemnani<br />

Priyanka Paul<br />

Rashika Desai<br />

Rutika Yeolekar<br />

Sameer Hadker<br />

Shruti Giri<br />

Taran <strong>War</strong>ner<br />

We are deeply grateful to Sasha Kalrani and Akshath Killa, our<br />

former Executive Director and former Head <strong>of</strong> Design.<br />

--<br />

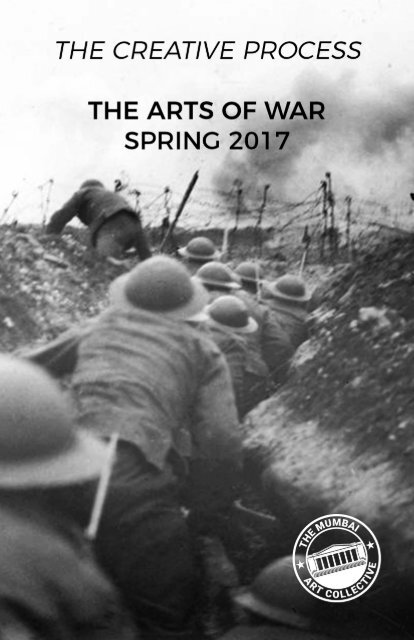

On Cover: A WWI photograph by Lt. John <strong>War</strong>wick Brooke,<br />

British Army photographer, via Imperial <strong>War</strong> Museums<br />

2

Acknowledgements<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

I would like to thank the entire TMAC team for making this edition<br />

<strong>of</strong> the magazine possible. It would not have been possible without<br />

the hard work and dedication <strong>of</strong> each and every one <strong>of</strong> you.<br />

Without having someone to ideate with, this magazine would have<br />

been impossible, and for that I would be indebted to Kabeer<br />

Khurana, Chintan Girish Modi, and Rajkamal Aich, all <strong>of</strong> whom<br />

graciously took time out <strong>of</strong> their busy days to hear me out and advise<br />

me.<br />

I am deeply indebted to all the artists and poets who took time out<br />

<strong>of</strong> their busy schedules to talk with us, and agree to follow up<br />

interviews. Thank you, for opening up to us, and letting us in so we<br />

could conduct genuine and authentic interviews.<br />

Last but not the least, I would like to thank Pr<strong>of</strong>. Barbara Will, Pr<strong>of</strong>.<br />

Colleen Boggs, Pr<strong>of</strong>. Katherine Hornstein, and Pr<strong>of</strong>. Laura<br />

Edmondson, for a spectacular class I took in the Fall at Dartmouth<br />

College, that shares its name with the title <strong>of</strong> this edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong>. It was in this class where I was exposed to the <strong>Arts</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>, and served as the inspiration for this edition <strong>of</strong> the<br />

magazine. Thank you for all the advice, help, and support.<br />

And to you, the reader, for taking the time to read, and to think<br />

about the articles presented in this edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong>.<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Ishaan Jajodia<br />

3

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

Editorial Note: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Dear Reader,<br />

T<br />

he world is at war. From Syria to Iraq, India to Pakistan, the<br />

world is now at a stage where conflict has become the new<br />

normal. From the beginning <strong>of</strong> time, conflict has given<br />

society the most pr<strong>of</strong>ound and celebrated art. Thus, it is only apt<br />

that this issue be dedicated to the arts <strong>of</strong> war.<br />

Art is as responsible for starting war as it is for sustaining it and<br />

ending it. It has the ability to significantly alter public perceptions<br />

<strong>of</strong> war, and to sustain mass movements for and against aggression<br />

and violence.<br />

AN ETCHING FROM THE DISASTERS OF WAR BY FRANCISCO GOYA,<br />

RECOUNTING THE FRENCH INVASION AND ANNEXATION OF SPAIN IN THE<br />

FIRST DECADE OF THE 19TH CENTURY.<br />

4

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

When Francisco Goya rendered his heart-wrenching series <strong>The</strong><br />

Disasters <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>, and Jacques Callot created <strong>The</strong> Miseries <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>, little<br />

did they know the impact their recognition <strong>of</strong> the hardships that<br />

civilians and soldiers face in war alike. A significant part <strong>of</strong> previous<br />

artwork served to glorify the idea <strong>of</strong> war, and to euphemise the<br />

horrors <strong>of</strong> it. <strong>War</strong> is no a gentleman’s game, rather, a game <strong>of</strong> life<br />

and death. Art was an important part <strong>of</strong> the Napoleonic propaganda<br />

machine, where the neoclassical tradition <strong>of</strong> history and battle<br />

painting was adapted to represent contemporary events and present<br />

a version <strong>of</strong> ‘truth’ that suited narratives that the Empire intended<br />

to promote.<br />

Moving eastwards from the western tradition, we come across<br />

remarkable works <strong>of</strong> art in India that talk about war. Indian literary<br />

and artistic history has constantly featured the theme <strong>of</strong> conflict in<br />

a prominent manner. Like the Iliad and the Aeneid, the two most<br />

renowned Indian epics talk about different types <strong>of</strong> war. <strong>The</strong><br />

Ramayana’s rising action arises from a war that Rama wages to save<br />

his wife from the abductor, the King <strong>of</strong> Lanka, Ravana. <strong>The</strong><br />

Mahabharata, the largest epic ever written, focuses on fratricide and<br />

war between the Kaurava and Pandava brothers. It is no coincidence<br />

that two <strong>of</strong> Hinduism’s most prominent epics talk <strong>of</strong> injustice and<br />

war.<br />

5

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

LORD CLIVE MEETING WITH MIR JAFAR AFTER THE BATTLE OF PLASSEY, OIL<br />

ON CANVAS (FRANCIS HAYMAN, C. 1762)<br />

India has a rich history <strong>of</strong> being at war. At no point in time was the<br />

nation, as it stands today, a single country. Composed <strong>of</strong> a few major<br />

kingdoms, and hundreds <strong>of</strong> smaller principalities, war was a<br />

common occurrence. <strong>The</strong> role <strong>of</strong> art in these conflicts can not be<br />

mistaken, whether it is the poetry or the murals commissioned by<br />

royals <strong>of</strong> all power levels. Art, <strong>of</strong>tentimes, acts as a bridge between<br />

the wishful imagination <strong>of</strong>ten served to us as Indian history, and the<br />

truth <strong>of</strong> what happened.<br />

Regardless <strong>of</strong> the position that artwork takes on the justness <strong>of</strong><br />

conflict, it can safely be ascertained that art is integral to<br />

conversations about war. By depicting “the iconography <strong>of</strong><br />

suffering,” as Susan Sontag mentions in her book Regarding the Pain<br />

<strong>of</strong> Others, and exploring its larger implications through art, this issue<br />

<strong>of</strong> the magazine hopes to sensitise its readers about war and death.<br />

We present art and artists as an entry point into something that is<br />

almost fundamental to human life- war.<br />

6

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong> team wishes that the reader examine these<br />

works and critiques closely, and think <strong>of</strong> the larger implications that<br />

these works and stories occupy in the master narratives that are being<br />

marketed today. <strong>The</strong> world is changing, and it is at war. But we must<br />

also know what it means.<br />

If you feel like you want to talk to us about any <strong>of</strong> the articles, or<br />

want to correspond and initiate a conversation with the TMAC<br />

team, email us at letters@themumbaiartcollective.com, and we will<br />

be happy to carry it forward.<br />

<strong>War</strong>m Regards,<br />

Ishaan Jajodia.<br />

Editor, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong>.<br />

--<br />

7

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

What’s Inside?<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

MASTHEAD & PUBLISHER INFORMATION 1<br />

THE MUMBAI ART COLLECTIVE TEAM 2<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3<br />

EDITORIAL NOTE: THE ARTS OF WAR 4<br />

WHAT’S INSIDE? 8<br />

CONFLICT IN THE VĀLMĪKI RĀMĀYANA: A SOUTH ASIAN<br />

PERSPECTIVE ON JUST WAR THEORY 10<br />

THE RUINS OF WAR AND COLONIALISM IN AMITAV<br />

GHOSH’S THE GLASS CASTLE 18<br />

BALWAN, KAUSIK. 24<br />

“I WRITE ON WAR BECAUSE I DON’T GET SLEEP AT<br />

NIGHT”: DAANIYAL SAYED 28<br />

SANITISING WAR: DECONSTRUCTING INDIAN WAR<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY FROM THE KARGIL WAR (1999) 34<br />

THE BARD FROM THE VALLEY 42<br />

BURNT MUSINGS: WAR 48<br />

ENDNOTE 52<br />

--<br />

8

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

9

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Conflict in the Vālmīki Rāmāyana: A South<br />

Asian Perspective on Just <strong>War</strong> <strong>The</strong>ory<br />

10

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

PAINTING: RAJA RAVI VARMA’S RENDITION OF RAVANA FIGHTING THE<br />

VULTURE JATAYU, WHILE ABDUCTING SITA, RAMA’S WIFE.<br />

S<br />

ince time immemorial, it has been ingrained in our minds that<br />

the central theme <strong>of</strong> the Rāmāyana is the war between<br />

darkness and light, and the subsequent victory <strong>of</strong> good over<br />

evil. Most variants <strong>of</strong> the Rāmāyana, like the Kampanrāmāyanam,<br />

appear to preach the same; with their black-and-white heroes and<br />

villains, and clear-cut definitions <strong>of</strong> what is good and what is evil.<br />

Rāma, the divine Vishnu avatar, is the epitome <strong>of</strong> goodness and the<br />

very embodiment <strong>of</strong> justice, while Rāvana, the Rākshasa, is a symbol<br />

<strong>of</strong> evil, greed, lust—all vices that a ‘moral’ individual should not<br />

indulge in.<br />

However, in other retellings, the characters are portrayed as morally<br />

grey: there are no watertight categories <strong>of</strong> ‘good’ and ‘evil’. Rāma is<br />

not perfect; he is not a god, but rather a god-man who has to live<br />

within the confines <strong>of</strong> mortality with all its vicissitudes. Similarly,<br />

Rāvana is not always evil; many retellings paint him as a tragic figure<br />

undone by his passions. In light <strong>of</strong> these revelations, the war<br />

between Rāma and Rāvana may not have been the just outcome we<br />

presume it to be, and indeed, a closer analysis tells a different story.<br />

An framework for analyzing the conflict between Rama and Ravana<br />

would be the just war theory, a doctrine <strong>of</strong> military ethics first<br />

formalised by Stanisław <strong>of</strong> Skarbimierz, a Polish rector. It lays down<br />

seven criteria—all <strong>of</strong> which must be met—to justify war. I will not<br />

be presenting all seven <strong>of</strong> them: the Rāmāyana war cannot be<br />

reconciled with at least one <strong>of</strong> the four criteria <strong>of</strong> right cause, right<br />

intention, last resort, and right conduct, thereby breaching the<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> a ‘just’ war. This in turn illustrates the fact that war is not<br />

a simple do-or-do-not situation: it is a complicated layered event<br />

11

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

shaped by circumstances and ‘moralistic’ principles. <strong>The</strong>re are far too<br />

many retellings <strong>of</strong> the Rāmāyana; here we focus mostly on the<br />

Vālmīki Rāmāyana for the narratives and plot structures.<br />

It would be helpful to first present the circumstances that caused the<br />

war. When Rāma and Lakshmana leave Sitā in their hut in pursuit<br />

<strong>of</strong> the golden deer that Sitā desired, Ravana kidnaps Sitā. Vowing<br />

revenge, Rāma, aided by the Vānara, wages war on Rāvana, and<br />

defeats him. However, why precisely did Rāma wage war on<br />

Rāvana? Were there other reasons besides bringing his wife back,<br />

and did these reasons rationalise the use <strong>of</strong> violence?<br />

RIGHT CAUSE<br />

Is there an appropriate cause to justify violence? In the Vālmīki<br />

Rāmāyana, the sanctity <strong>of</strong> the world is endangered by demons who<br />

terrorise Brahmin sages and defile their rituals, so the gods call upon<br />

Vishnu to restore its purity. Vishnu takes the form <strong>of</strong> Rāma, whose<br />

sole mission in life is to end the demons’ menace for which he must<br />

face Rāvana (who is the leader <strong>of</strong> the demons) in battle. This predecided<br />

calling to restore cosmic balance seems to justify the<br />

bloodshed in the Rāmāyana. It is said that in waging <strong>of</strong>fensive war<br />

against Rāvana, Rāma is not only condemning the violence and evil<br />

that Ravana is committing, but also the targeting <strong>of</strong> said violence<br />

towards ascetics <strong>of</strong> the religious principle <strong>of</strong> Hinduism as<br />

well. Moreover, Rāma is further authorized to kill violent forces and<br />

therefore protect the world by virtue <strong>of</strong> being born as a Kshatriyā,<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the warrior caste. By a slightly twisted logic, this principle<br />

does not seem to have been violated.<br />

RIGHT INTENTION<br />

Right intention is a subset <strong>of</strong> right cause. We may define this as<br />

whether the motivation behind upholding righteousness is pure and<br />

12

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

independent <strong>of</strong> selfish desires. For Rāvana, the intent seems to be to<br />

promote conflict—it is thus self-serving and hence condemned.<br />

However, Rāmā falters here as well. <strong>The</strong> desire to get his wife back<br />

(which is what the intention seems to be at first glance) is selfserving,<br />

for all intents and purposes. However, in many places in the<br />

Rāmāyana, Rāmā mentions that he is not retrieving his wife out <strong>of</strong><br />

affection for her; rather, it is to redeem his lost honor. He carelessly<br />

mentions this in the Yuddha Kāṇḍa, when Sitā is brought out to<br />

him, all decked up. He tells her that she is free to go, now that the<br />

prestige <strong>of</strong> his clan has been restored. He further goes on to say that<br />

she could now choose to be with Sugrīva, Vibhīshana, or even his<br />

brothers –clearly all lesser beings (pardon my usage <strong>of</strong> the term) than<br />

him. Rāmā thus redeems himself by waging war, and then seeks to<br />

absolve himself <strong>of</strong> any blame in Sitā’s misfortunes by disassociating<br />

himself from her. Further, the suggestion that she should now<br />

associate herself with less-godly men is something that I see as a<br />

mark <strong>of</strong> arrogance and an indication <strong>of</strong> the fact that Sitā was merely<br />

a tool for self-preservation; now that the job is done Rāmā has no<br />

use for her anymore, and in fact would leave her to beings less<br />

accomplished than him. I feel that leaving her to lesser-beings also<br />

indicates that he cares only about himself, it does not matter if others<br />

have to face the consequence <strong>of</strong> having an unchaste (since that is<br />

what Rāmā presumes about Sitā) wife. Many would justify this by<br />

saying that as long as the cosmic balance <strong>of</strong> the universe was<br />

restored, such individual actions need not matter. I would, however,<br />

prefer to discard this utilitarian notion with respect to this point. I<br />

feel that both Rāmā and Rāvana waged war with the wrong<br />

intention. This criterion <strong>of</strong> the just war theory has been violated.<br />

LAST RESORT<br />

More important than that, however, is whether war was absolutely<br />

the last resort. Were all prior attempts at peace exhausted before the<br />

parties turned to war? It is interesting to note that when Rāmā is<br />

exiled by Dasharatha, he calmly accepts his fate, while Lakshmana<br />

13

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

is incensed. He goes so far as to say that “violent means are the only<br />

way to seize control, while leniency results in defeat” (II.18.8). Rāmā<br />

placates him and they go their way. When Sitā is kidnapped,<br />

however, Rāmā becomes uncharacteristically enraged, and it is<br />

Lakshmana who calms him. Many other instances in the text stress<br />

on the importance <strong>of</strong> peaceful means <strong>of</strong> resolving conflict, and the<br />

attempts made by Hanumān, Lakshmana, and Vibhīshana to resolve<br />

conflict via discourse. But because they are at the bidding <strong>of</strong> Rāmā,<br />

who has decided upon war, they are forced to engage in violence.<br />

What I find most interesting is that in both cases Rāmā loses his<br />

honor, but in the former the authoritative legitimacy <strong>of</strong> his father<br />

deems the cause not worthy <strong>of</strong> a rebellion. One <strong>of</strong> the tenets <strong>of</strong> the<br />

just war is the presence <strong>of</strong> a legitimate authority; something we will<br />

not go into much detail. However, Rāmā’s willingness to avoid war<br />

in face <strong>of</strong> his exile seems to stem from his obedience <strong>of</strong> his father’s<br />

wishes—in other words, a respect for authority. Many sociological<br />

studies suggest that this has something to do with caste –not only is<br />

Dasharatha a human, but he is also a Kshatriyā, the only caste<br />

allowed to wield weapons. Rāvana is half-Rākshasa, half-Brahmin;<br />

thus, both his caste and his demon blood (which also robs him <strong>of</strong><br />

humanly moral principles) deprive him <strong>of</strong> any legitimacy to wield<br />

weapons and wage war. It is <strong>of</strong>ten suggested that Rāmā declared war<br />

outraged at Rāvana’s audacity to declare himself king and adopt the<br />

ways <strong>of</strong> the Kshatriyā caste.<br />

<strong>The</strong> principle <strong>of</strong> last resort finds prominence in Rākshasa military<br />

ethics as well. Both Vibhīshana and Kumbhakarna chastise him and<br />

urge him to rethink his decisions. <strong>War</strong> is to be avoided whenever<br />

possible, and when it becomes inevitable, it is best to be on the side<br />

<strong>of</strong> the ‘righteous’ (as illustrated by Vibhīshana’s defection to Rāmā’s<br />

army). However, it is clear that both Rāmā and Rāvana avoid<br />

peaceful counsel. <strong>The</strong> principle <strong>of</strong> last resort has thus not been<br />

obeyed.<br />

14

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

RIGHT CONDUCT<br />

Military ethics during actual fighting are held in high regard in the<br />

Rāmāyana. Though we do not get to see deviation from these<br />

principles in the actual war, there are several other instances in the<br />

text which depict that both Rāmā and Rāvana were susceptible to<br />

disobeying these principles.<br />

In the Kiṣkindhākāṇḍa, Rāmā, in order to forge an alliance with<br />

Sugrīva, agrees to slay his brother Vāli. As Sugrīva and Vāli<br />

fight, Rāmā hides behind a tree and shoots an arrow at Vāli,<br />

breaking the code he has staunchly adhered to all this while. As Vāli<br />

lies dying, he reproaches Rāmā for his cruel act. Rāmā does not<br />

justify this action, but tries to nullify the military ethics by saying<br />

that they do not apply to animals. This disregard for ‘lesser’ beings<br />

perhaps foreshadows Rama’s callous behaviour with Sitā in the<br />

Yuddha Kāṇḍa. Besides, this goes on to show that the major<br />

alliances <strong>of</strong> this unjust (as we have already established) war were<br />

established on shaky grounds, further adding to its demerits.<br />

In contrast, Rāvana might well be commended for listening to his<br />

counsel as they steered him on the ethical path. Not only was<br />

Vibhīshana successfully able to talk him out <strong>of</strong> slaying Hanumān as<br />

slaying an emissary breaches the code, but he also listens to his<br />

counsel when they advise him against killing Sitā.<br />

Throughout the Rāmāyana, Rāmā recites several tenets <strong>of</strong> military<br />

ethics from time to time e.g. “a foe who does not resist, is in hiding,<br />

cups his hands in supplication, approaches seeking refuge, is fleeing,<br />

or is caught <strong>of</strong>f guard—[one] must not slay any <strong>of</strong> these” VI.37.78;<br />

however, he seems not to follow them (at least, the one about fleeing<br />

is violated when he kills Marīchā, who is in the guise <strong>of</strong> the golden<br />

deer). It would be fair to say that Rāmā is indeed hypocritical in his<br />

15

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

approach to right conduct; and it is Rāvana who (albeit reluctantly)<br />

upholds them. Nevertheless, this criterion, too, has been nullified.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

While the epic defies the logical principles <strong>of</strong> just war, it adheres to<br />

a Hindu code <strong>of</strong> moral supremacy. Throughout the Rāmāyana, great<br />

importance is placed on the morality <strong>of</strong> the leader, and nondefensive,<br />

punitive war is justified for the defence <strong>of</strong> morally superior<br />

ideas (Hindu cosmic balance, in this case); quite unlike western<br />

philosophical thought. Further, adhering to strong, defined moral<br />

principles allows a leader to gain and maintain political legitimacy.<br />

If we were to see this in the context <strong>of</strong> the principle <strong>of</strong> last resort, it<br />

may be inferred that since Rāvana’s ideology was not consistent with<br />

Rāmā’s, Rāmā did not deem him a legitimate ruler.<br />

Perhaps we may attribute the complex nature <strong>of</strong> the war to moral<br />

relativism; a concept most famously crafted by Plato and explored<br />

by Nietzsche, but rarely mentioned in Hinduism. <strong>The</strong>re is no<br />

universal moral philosophy that dictates a code for distinguishing<br />

right from wrong, and therefore there are different viewpoints on<br />

morality, each shaped by its culture, history and society; with no<br />

viewpoint considered superior over others. What to some may seem<br />

a clash between two males whose egos could not be adequately<br />

massaged without military slaughter, to others may be the coming<br />

<strong>of</strong> the divine Lord and the redemption <strong>of</strong> their sins. It is up to the<br />

reader to choose which camp they belong to.<br />

--<br />

Gauri Saxena is currently reading Economics and Anthropology at<br />

Ashoka University, where she serves as arts and culture editor <strong>of</strong> the<br />

university newsletter. She has previously been published in the<br />

Entartete Kunst Literary Review, <strong>The</strong> Bombay Review, and<br />

Alexandria Quarterly, amongst others.<br />

16

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

17

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Ruins <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> and Colonialism in Amitav<br />

Ghosh’s <strong>The</strong> Glass Castle<br />

18

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

T<br />

he Glass Palace (novel, 2000) by Amitav Ghosh, <strong>of</strong>fers a<br />

detailed critique on the effects <strong>of</strong> war and colonialism.<br />

Spanning across three countries and three generations, the<br />

book delves into the personal lives <strong>of</strong> Ghosh’s characters,<br />

intermingled with a sense <strong>of</strong> love along with the journey <strong>of</strong> life. This<br />

aura is much too <strong>of</strong>ten broken and interrupted by the horrors<br />

brought in by colonization and the consequent dislocation that it<br />

leads to.<br />

Starting <strong>of</strong>f with an introduction to an eleven-year-old orphaned<br />

Indian boy, Rajkumar, the story proceeds in Mandalay, Burma (now<br />

Myanmar), describing the circumstances that brought him here<br />

along with the sense <strong>of</strong> belonging he develops to the place.<br />

Rajkumar is introduced to Saya John, who becomes a father-figure<br />

in Rajkumar’s life. Later, the English rampage the city, but the<br />

soldiers are mainly Indians who have come on the orders <strong>of</strong> their<br />

colonial masters. Thus begins the general sense <strong>of</strong> chaos, ruin, and<br />

fleet that constitutes a major part <strong>of</strong> the book. With the invasion <strong>of</strong><br />

the British, the residents <strong>of</strong> the city seek refuge in the Glass Palace,<br />

where King <strong>The</strong>baw and his family used to rule and reside. What<br />

follows is the family’s exile to Ratnagiri (a port town in India),<br />

Rajkumar’s marriage to Dolly, a servant in the King’s household,<br />

followed by the birth <strong>of</strong> their sons Neel and Dinu and the<br />

intermingling <strong>of</strong> the families <strong>of</strong> Rajkumar, Saya John, and Uma in<br />

the three nations <strong>of</strong> Burma, Malaya, and India respectively. Set<br />

amidst the two world wars and British colonialism, the novel moves<br />

in a direction <strong>of</strong> establishing and then tearing relationships apart<br />

through death and dislocation, thus describing the ruthlessness and<br />

arbitrariness that war brings along.<br />

Throughout this novel, rich and abundant in details that spanned<br />

the history <strong>of</strong> the world in those several decades, the themes <strong>of</strong> war<br />

19

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

seem to constantly surface, bringing to light the reality <strong>of</strong> the<br />

otherwise fictitious characters. Most <strong>of</strong> the characters seem to<br />

become symbols <strong>of</strong> larger elements. Rajkumar, for instance, comes<br />

to represent and symbolize an entire migrated community and their<br />

ways <strong>of</strong> functioning in an alien land. <strong>The</strong> unfortunate yet inevitable<br />

deaths and separation <strong>of</strong> the characters represent the horrors <strong>of</strong> warthat<br />

no one can remain at a safe and alo<strong>of</strong> distance from it; that each<br />

individual is the victim <strong>of</strong> a force brought about by greed.<br />

Divided into seven parts, each section deals with an important<br />

aspect. <strong>The</strong> first part is called “Mandalay,” depicting the Anglo-<br />

Burmese <strong>War</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1885. It focuses on the crude greed that drives all<br />

individuals alike; this greed is shown to transcend one’s status, race,<br />

caste, group, or nation. Furthermore, the plunder shown throughout<br />

this part serves as an exposure <strong>of</strong> the raw greed <strong>of</strong> the colonizers,<br />

which led them to loot and control their colonies in the brutal<br />

manner that they did. <strong>The</strong> second part, called “Ratnagiri,” shows<br />

colonial subjugation and imperial dominance. With the merge <strong>of</strong><br />

Burma with India as a single colonial subject, the attitudes to<br />

surrender oneself and the contrasting attitudes to resist are<br />

presented. <strong>The</strong> third section, “<strong>The</strong> Money Tree,” shows how<br />

Rajkumar prospers through timber business. <strong>The</strong> fourth section,<br />

called “<strong>The</strong> Wedding,” deals with the second generation.<br />

Rajkumar’s son Neel marries Manju, and people like Arjun and<br />

Dinu show fascination for the British. <strong>The</strong> fifth section, “Morning<br />

Side” depicts the consequence <strong>of</strong> the Second World <strong>War</strong> in Malaya.<br />

<strong>The</strong> penultimate section, “<strong>The</strong> Front,” depicts how characters suffer<br />

due to the outbreak <strong>of</strong> the Second World <strong>War</strong>. <strong>The</strong> last section <strong>of</strong><br />

the novel titled “<strong>The</strong> Glass Palace,” deals with the Indian National<br />

Movement at its peak and India’s final achievement <strong>of</strong><br />

independence.<br />

20

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

In the opening scene, Ghosh describes how the marching soldiers<br />

looked like to the Burmese crowd- “<strong>The</strong>re was no rancour on the<br />

soldiers’ faces, no emotion at all. None <strong>of</strong> them so much as glanced at the<br />

crowd.” This reflects the inhumanity that developed within the<br />

minds <strong>of</strong> the people as a result <strong>of</strong> war. This is reiterated by Saya John<br />

when he says,<br />

“…their willingness to kill for their masters, to<br />

follow any command, no matter what it entailed?<br />

And yet, in the hospital, these sepoys would give<br />

me gifts, tokens <strong>of</strong> their gratitude. I would look<br />

into their eyes and see also a kind <strong>of</strong> innocence, a<br />

simplicity. <strong>The</strong>se men, who would think nothing<br />

<strong>of</strong> setting fire to whole villages if their <strong>of</strong>ficers<br />

ordered, they too had a certain kind <strong>of</strong> innocence.<br />

An innocent evil. I could think <strong>of</strong> nothing more<br />

dangerous.”<br />

This sense <strong>of</strong> being mentally controlled is also reflected in the<br />

Collector, who was “haunted by the fear <strong>of</strong> being thought lacking by his<br />

British colleagues,” as well as in the character <strong>of</strong> Arjun, who remained<br />

loyal to his duty towards the British for a major part <strong>of</strong> his short life.<br />

Dinu, similarly, fails to realize that the British, much like Hitler and<br />

Mussolini, are ruling through racialism, aggression and conquest.<br />

He, like several other Indians who received a primarily one-sided<br />

Western education, does not question the immorality <strong>of</strong> the British.<br />

This was, truly, the aim with which Western education was<br />

introduced in India, as clearly stated by Macaulay (who was<br />

responsible for the same).<br />

Edward Said, one <strong>of</strong> the founders <strong>of</strong> the academic field <strong>of</strong><br />

postcolonial studies, writes, ‘No one today is purely one thing.<br />

Labels like Indian, or woman, or Muslim, or American are not more<br />

21

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

than starting-points, which if followed into actual experience for<br />

only a moment are quickly left behind. Imperialism consolidated the<br />

mixture <strong>of</strong> cultures and identities on a global scale. But its worst and<br />

most paradoxical gift was to allow people to believe that they were<br />

only, mainly, exclusively, white, or Black, or Western, or Oriental.’<br />

This theme resonates throughout the novel, throughout, in fact, the<br />

course <strong>of</strong> colonial history. <strong>War</strong> and colonialism brought about a<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> hybridity among races <strong>of</strong> the world- reflecting, in a way, the<br />

fact that no race is pure; yet, this purity <strong>of</strong> race was highly<br />

emphasized upon by the colonizers. In this novel, similarly, readers<br />

find that all the relationships made throughout the three generations<br />

go beyond the narrow-mindedness <strong>of</strong> maintaining a pure race. <strong>The</strong><br />

opposite, in fact, is where the basis <strong>of</strong> the novel lies on- a<br />

homogenized global culture arising out <strong>of</strong> heterogeneity, yet<br />

targeted by the ‘superior White’ race.<br />

<strong>The</strong> novel also focuses on the journey <strong>of</strong> life and the process <strong>of</strong><br />

growing. One watches all the characters grow in their opinions.<br />

Arjun, a soldier himself, is later disillusioned about the British, finds<br />

an anti-colonial consciousness and seeks to join the movement<br />

towards India’s independence. Thus follows a ‘decolonization <strong>of</strong> the<br />

mind’ (Ngugi wa Thiong’o, 1986) <strong>of</strong> Arjun as well as his fellow<br />

soldiers. Similarly, Uma, while initially prone to an almost<br />

aggressive sense <strong>of</strong> nation and community, later develops the nonviolent<br />

view. She admits to the need <strong>of</strong> attaining reform <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Indian society along with its independence.<br />

Thus, this novel is essentially an amalgamation <strong>of</strong> war, dislocation,<br />

love and death, exile, and helplessness. It reflects on the point <strong>of</strong><br />

view <strong>of</strong> the colonized, and in doing so, never leaves South Asia.<br />

Ghosh, speaking about his novels, said, “My fiction has always been<br />

about places that are states in the process <strong>of</strong> coming unmade or<br />

communities coming unmade or remaking themselves in many<br />

22

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

ways.” While focusing on the modus operandi <strong>of</strong> colonization in<br />

Burma, the focus in India is on how colonialism unified the country<br />

in an anti-colonial embrace, and how it evolved an anti-colonial<br />

psyche in Malaya. <strong>The</strong> three nations have a shared history <strong>of</strong> being<br />

born out <strong>of</strong> an anti-imperialist struggle, and being torn, shaped, and<br />

reformed by the consequences brought about by the wars fought in<br />

those decades. <strong>The</strong> Glass Palace questions the very essence <strong>of</strong> war<br />

by being ruthless in its description <strong>of</strong> war’s reality, and refuses to<br />

cater to a notion that euphemizes the adversity it brings about.<br />

Indeed, the question posed by Ghosh can be summed up by a line<br />

from the novel itself-<br />

“Was this how a mutiny was sparked? In a<br />

moment <strong>of</strong> heedlessness, so that one became a<br />

stranger to the person one had been a moment<br />

before? Or was it the other way around? That this<br />

was when one recognized the stranger that one<br />

had always been to oneself; that all one’s loyalties<br />

and beliefs had been misplaced?”<br />

--<br />

Rashika Desai is pursuing <strong>Arts</strong> at St. Xavier's College, Mumbai. She<br />

is a bibliophile and enjoys reading and writing poetry, who wants to<br />

learn as many languages as she can.<br />

23

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

Balwan, Kausik.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

BALWAN BY KAUSIK MUKHOPADHYAY/ IMAGE: THE GUILD ART GALLERY<br />

Kausik grew up and went to art school at a time when the established<br />

status quo was anti-Dada, anti-Duchamp, and anti-Abstraction.<br />

<strong>The</strong> degeneracy and disdain that these art movements were regarded<br />

with fostered a pushback in the minds <strong>of</strong> artists like Kausik. Stifled<br />

by the expressly descriptive mode <strong>of</strong> representation, he recounts<br />

conversations with fellow artist Tushar Jog, he attempted to wrangle<br />

with the conceptual ideas that Duchamp bought out in his<br />

Readymades, questioning the role <strong>of</strong> the hand <strong>of</strong> the artist, <strong>of</strong> the role<br />

<strong>of</strong> the installation, and other fundamental questions on the nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> art. And it is with this in mind, that Kausik picks the two soldiers<br />

that waltz around the piece, directionless, and without any agency.<br />

<strong>The</strong> “badly-made GI Joe” toys, as Kausik describes them, remind<br />

24

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

the viewer that children, too, are playing with Weapons <strong>of</strong> Mass<br />

Destruction, conspiring to make war, not love.<br />

However, Duchamp’s works still glossed over and idealised the<br />

struggles <strong>of</strong> life. Kausik’s Balwan is a pushback against the<br />

idealisation and fetishisation <strong>of</strong> violence and war. He tells TMAC,<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Mughal miniatures were violent as well. We were never really<br />

free <strong>of</strong> violence.” And in a way, Kausik is right. A lot <strong>of</strong> the<br />

underlying tension in representations <strong>of</strong> the Hindu epics and the<br />

painting tradition <strong>of</strong> the martial Rajputs indicate impending<br />

violence. For Kausik, this glorification <strong>of</strong> violence is abhorrent, and<br />

the attempt to represent war as glory is a blot on the conscience <strong>of</strong><br />

the artist.<br />

Behind the creation <strong>of</strong> Balwan is a commentary on consumerism as<br />

it manifests itself in the art world. Kausik is fully aware <strong>of</strong> the<br />

traditions <strong>of</strong> the artists that came before him, and while mentioning<br />

<strong>War</strong>hol, reminds one <strong>of</strong> the nature <strong>of</strong> the buyer. <strong>The</strong> art world is a<br />

market, where demand meets supply, and Kausik believes that “art<br />

is (now) a thing to satisfy your customer.” <strong>The</strong> reductivism that<br />

marks Kausik’s works is different, for it is meant to be homely, not<br />

to be consumerist. This is also why Kausik’s installations are not<br />

meant to last, and the materials are recycled into other installations.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ephemeral nature <strong>of</strong> Kausik’s art is a recognition <strong>of</strong> the<br />

commercialisation <strong>of</strong> art, for if art no longer exists, it cannot be sold.<br />

Ranjit Hoskote’s catalogue essay for an exhibition that marked<br />

Kausik’s return to the art world reads:<br />

Adopting a DIY aesthetic as he does,<br />

Mukhopadhyay turns his back on the kind <strong>of</strong> high<br />

finish that has been de rigueur in much<br />

postcolonial Indian art. However, the rough edges<br />

25

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

are deceptive; his bricolage embodies a<br />

sophisticated play with multiple historical<br />

horizons.<br />

Kausik’s fellow pr<strong>of</strong>essor at KRVIA, where he teaches, Sonal<br />

Sundararajan, writes about his work:<br />

This is the sort <strong>of</strong> meta story that hovers over the<br />

table, like a spectral ghost. Of a time <strong>of</strong> such<br />

fleeting obsolescence that barely have you been<br />

able to call something your own, that another<br />

comes to replace it. <strong>The</strong> detritus <strong>of</strong> a time <strong>of</strong> a<br />

perpetual present, <strong>of</strong> a time <strong>of</strong> ‘nostalgia for only<br />

the present’ piles up higher and higher - in the<br />

shops in chor bazaar, in the scrap markets, in the<br />

landfills, in attics and cupboards. Perhaps in all<br />

the exiled and discarded objects lying at the<br />

margins lie the repressed desires <strong>of</strong> the home and<br />

the city.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most pressing questions that the use <strong>of</strong> discarded articles<br />

raises for the viewer is about the nature <strong>of</strong> memory. Is our memory<br />

<strong>of</strong> war dictated as much by what is not told through generations and<br />

through cultural and historical archives? Kausik would seem to agree<br />

with this proposition. <strong>The</strong> fleeting nature <strong>of</strong> memory, and its<br />

inherent inconsistency is highlighted by putting two soldiers who<br />

waltz around in the water, with no idea <strong>of</strong> they are truly doing, stuck<br />

in an animated suspension. Are they truly the Balwans that the piece<br />

is titled after?<br />

26

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> piece is titled Balwan, which means strong and hearty in Hindi.<br />

But by choosing a word that has a presence in both Urdu and Hindi,<br />

languages spoken across the Indian subcontinent, Kausik ties this<br />

piece back to the Indo-Pakistan conflict. <strong>The</strong> piece, therefore has<br />

cross-border significance. Deprived <strong>of</strong> any indicator <strong>of</strong> nationality,<br />

Kausik’s piece portrays the universality <strong>of</strong> war, built carefully behind<br />

a façade <strong>of</strong> crudeness and simplicity. Sometimes, the soldiers are in<br />

conflict with each other, and sometimes they aim into abstraction<br />

with something. <strong>The</strong> piece presents this to remind viewers <strong>of</strong> the<br />

recent nature <strong>of</strong> the Partition, for we still retain significant aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> culture that the Indian subcontinent espoused. <strong>The</strong> conflict<br />

between the two, is therefore portrayed as fratricidal. Alluding to his<br />

Mannerist predecessors, Kausik’s title is also emblazoned on the<br />

outer wall <strong>of</strong> the tub in which the sculpture is contained, reading<br />

“Balwan size.” Is one form <strong>of</strong> bravery better and bigger than any<br />

other?<br />

With Kausik’s piece, I find myself wrangling with the question <strong>of</strong><br />

agency. <strong>The</strong>re is always the question <strong>of</strong> responsibility in war, for who<br />

is truly responsible for the horrors <strong>of</strong> war, we do not know, and<br />

probably will never know. This again brings up the question, Is art<br />

inherently political? For Kausik, the forms that constitute art are<br />

most definitely political. It is what the artist chooses to do with these<br />

forms is what influences the nature <strong>of</strong> the end product. Art, as<br />

Kausik sees it, has the potential to bring about social change, and it<br />

is with this in mind that Kausik crafts a narrative through a piece<br />

that lives as we breathe.<br />

--<br />

Ishaan Jajodia<br />

27

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

“I write on war because I don’t get sleep at night”:<br />

Daaniyal Sayed<br />

A PHOTOGRAPH OF IDLIB AFTER THE CHEMICAL BOMBING/ AL JAZEERA<br />

O<br />

n Wednesday, April 5, <strong>2017</strong>, the Syrian government<br />

used chemical weapons on the people <strong>of</strong> Idlib, Syria. This<br />

was not the first instance <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> chemical weapons by<br />

the Syrian government on its own people, having done so previously<br />

in August 2013. It is the indiscriminate killing <strong>of</strong> civilian<br />

populations that affects Daaniyal highly, and while talking with<br />

TMAC, uses this as an entry point into his poetry on the horrors <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>War</strong>.<br />

Born and brought up in Bombay, Daaniyal’s journey with the<br />

spoken and written word began through rap written about partying<br />

and love. He still writes poetry about Pyaar (love)<br />

and Mohabbat (affection), but only does it to distract himself from<br />

the horrors <strong>of</strong> war, he tells us. In many ways, Daaniyal’s evolution<br />

from Rapper to Poet was an evolution <strong>of</strong> the consciousness and the<br />

thoughtfulness, enabling him to become a poet that explores serious<br />

28

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

issues with his work. What separates Daaniyal from a significant<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the poetry tradition and community in Bombay is that he<br />

writes about pyaar andmohabbat when he is trying to get his mind<br />

<strong>of</strong>f the horrors <strong>of</strong> war, unlike his peers, who, according to him, have<br />

an almost single minded focus on these things.<br />

Daaniyal’s work <strong>of</strong>tentimes talks about the horrors <strong>of</strong> war. His<br />

sensitive nature can be traced back to his childhood. His heightened<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> emotive perception is key to his view on war, which he<br />

believes is inherently immoral. Pain and suffering is also vital to his<br />

view on war, and he recounts viewing a video (warning: graphic<br />

content) <strong>of</strong> a child following the chemical attack on Idlib. <strong>The</strong><br />

vacant stare <strong>of</strong> the child, clearly in pain, haunted Daaniyal, who said<br />

that “their eyes talk to him.” This was instrumental in prompting<br />

him to think about the repercussions <strong>of</strong> warfare, and his<br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> the iconography <strong>of</strong> suffering (Susan<br />

Sontag, Regarding <strong>The</strong> Pain <strong>of</strong> Others) makes him a more conscious<br />

person, for his conversations about his work are an implicit<br />

recognition that behind the facade <strong>of</strong> glory and victory lies a world<br />

wrought with destruction, with lives torn apart.<br />

29

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

This poem was written by Daniyal in response to the attacks in Idlib,<br />

Syria. Accompanying the poem was this statement by him:<br />

“P.S — a lot <strong>of</strong> people ask me, kya ghuma phiraa<br />

k Syria, Yemen pe aajata hai tu?<br />

When will you stop writing about it?<br />

I always have the same reply: When will the war<br />

stop?”<br />

Daaniyal’s poetry is not just a plea for appeasement, but also a cry<br />

against the sanitisation <strong>of</strong> war. <strong>The</strong> poem that he presents in<br />

response to the horrific attack, one that he recounts in graphic detail,<br />

is a cooptation <strong>of</strong> the horrors <strong>of</strong> war, and the creation <strong>of</strong> a second<br />

memory by someone who has never stepped foot inside Syria and<br />

Yemen. Daaniyal tells TMAC that “When someone innocent dies,<br />

30

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

I feel my own brother died.” Being a silent spectator, too, is a<br />

cooptation <strong>of</strong> the pornography <strong>of</strong> killing (Georges Didi-Huberman),<br />

and for Daaniyal, even when one person is killed as the result <strong>of</strong><br />

violence and war, the seven billion people <strong>of</strong> the world who are<br />

standing “in the field” must hang their heads in guilt and shame. We<br />

all have the blood <strong>of</strong> the dead on our hands, and we are complicit in<br />

their killing, either by consuming this pornography <strong>of</strong> killing, or by<br />

doing nothing about it. While Daaniyal acknowledges that <strong>War</strong> is<br />

inherently universal, he insists on grounding his poetry in more<br />

specific terms. His case in point is Syria and Yemen, two previously<br />

prosperous nations ravaged by recent conflict, and he considers that<br />

the world is already fighting the Third World <strong>War</strong>. His poetry is a<br />

plea for peace, and for democracy.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> Daaniyal’s work also focuses on the war going inside India,<br />

in our hinterlands: the war <strong>of</strong> religion, and <strong>of</strong> communal<br />

31

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

polarisation. <strong>The</strong> politics <strong>of</strong> beef is central to his, for Daaniyal<br />

mentions what he considers “hypocrisy” on part <strong>of</strong> the Bhartiya<br />

Janata Party, India’s ruling Hindu fundamentalist party, who<br />

promote beef in the North East, and ban it everywhere else. This is<br />

war for Daaniyal, too, but a war <strong>of</strong> different proportions. He is a<br />

proud Indian, but he says that he cannot afford to turn a blind eye<br />

towards the politics <strong>of</strong> polarisation that plagues the subcontinent’s<br />

political discourse. His grim view <strong>of</strong> the current crop <strong>of</strong> politicians<br />

is a clarion call to those who believe in the principles and values <strong>of</strong><br />

the classical liberal, and the grim view he espouses <strong>of</strong> politicians<br />

being solely utilitarian creatures is supported by a long list <strong>of</strong><br />

evidence. His poetry, again, serves as an outlet for his sensitive<br />

nature, and it is his way <strong>of</strong> being more than just a silent spectator.<br />

Speaking out by writing and performing poetry, is his way <strong>of</strong> coping<br />

with this.<br />

Daaniyal occupies a unique position in the poetry community, not<br />

just because <strong>of</strong> the subject matter <strong>of</strong> a significant portion <strong>of</strong> his work,<br />

but because <strong>of</strong> the languages that he chooses to write in. Despite<br />

knowing Hindi, Urdu, and English, almost all <strong>of</strong> his work is<br />

exclusively focused on the first two. His lexis and register, when he<br />

writes, is simple, yet impactful. He is no Hemingway, choosing<br />

instead to follow the path <strong>of</strong> a war-focused Robert Frost.<br />

Throughout his work, Daaniyal is cognisant <strong>of</strong> rhymes, and<br />

leverages the language and his vocabulary to begin a conversation<br />

with the reader. His poetry is a portrayal <strong>of</strong> mediated angst, the<br />

manifestation <strong>of</strong> this second memory that he talks about.<br />

32

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

PHOTO COURTESY: DAANIYAL SAYED<br />

His poetry is no call for violence. When he talks about his work, his<br />

focus is almost exclusively on empathising with victims <strong>of</strong> conflict<br />

and violence, lacking signs <strong>of</strong> hatred. <strong>The</strong>re is a clear sense <strong>of</strong> disgust<br />

at what is happening, but at no point in time does he let the feeling<br />

<strong>of</strong> hatred overpower his work. His poetry is a mediation between the<br />

different parts <strong>of</strong> his conscience, and in its final form, is<br />

overwhelming for both the listener and the reader. His<br />

representation <strong>of</strong> war is neither populist, nor inherently political. It<br />

is humanist, and pacifist, and for a poetry pundit to politicise it would<br />

be a mark <strong>of</strong> disrespect to the brilliance and conscience <strong>of</strong> his body<br />

<strong>of</strong> work.<br />

--<br />

Ishaan Jajodia<br />

Poetry Layout: Daaniyal Sayed<br />

33

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Sanitising <strong>War</strong>: Deconstructing Indian <strong>War</strong><br />

Photography from the Kargil <strong>War</strong> (1999)<br />

“<strong>War</strong> is propagated by myth and myth makers,<br />

and photography is an integral element <strong>of</strong> this<br />

myth.”<br />

I<br />

n the winter <strong>of</strong> 1998-1999, Pakistani army regulars disguised<br />

as reactionary militants illegally attempted to take over peaks<br />

<strong>of</strong> mountains in the Kargil-Dras region <strong>of</strong> Kashmir. This area<br />

was strategically important for India because it overlooked<br />

NH-1A, the sole road link to the region <strong>of</strong> Leh-Ladakh. When the<br />

ice thawed, local shepherds reported the intrusion, leading to the<br />

mass deployment <strong>of</strong> Indian troops, resulting in the Kargil <strong>War</strong>. <strong>The</strong><br />

Kargil <strong>War</strong> was the last conventional war that India fought against<br />

its neighbor, Pakistan, in 1999, and the first war which was reported<br />

on as it happened, through television and traditional news sources.<br />

According to the Kargil Review Committee, chaired by K.<br />

Subrahmanyam, the increased media exposure during the Kargil<br />

<strong>War</strong> “knit the country together as never before.” By examining the<br />

body <strong>of</strong> photography that survives from this war, it is possible to<br />

deconstruct the myths they aim to construct and reinforce.<br />

34<br />

WHO TOOK THESE IMAGES?<br />

While looking at the entire body <strong>of</strong> photography that survives from<br />

the Kargil <strong>War</strong>, one area was <strong>of</strong> particular interest: the general lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> attribution to the photographers and outlets responsible for the<br />

publication <strong>of</strong> the photographs. Poor implementation <strong>of</strong> intellectual<br />

property laws and a general lack <strong>of</strong> responsibility to attribute work<br />

to their creators hampers any attempts to further know their true<br />

progeny. Strangely, despite the extensive coverage <strong>of</strong> the war by<br />

television outlets, there seems to be no record <strong>of</strong> any photography

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

by them. Some <strong>of</strong> the images <strong>of</strong> jawans seem like candid shots,<br />

veering more towards personal mementos <strong>of</strong> the war rather than the<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> war documented for their news value.<br />

While a study <strong>of</strong> previous Indian war photography from the Indo-<br />

Pakistan <strong>War</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1965 reveals a multitude <strong>of</strong> photographs attributed<br />

to the Photo Division <strong>of</strong> the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Information and<br />

Broadcasting, the possibility also exists <strong>of</strong> the Press Corps <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Indian Army and other armed forces releasing images through their<br />

respective channels. <strong>The</strong>re may be an underlying reason behind the<br />

highly possible, controlled dissemination <strong>of</strong> images <strong>of</strong> the war<br />

without attribution to a particular person: to prevent the rise <strong>of</strong> the<br />

cult <strong>of</strong> the individual photographer. <strong>War</strong> photographers tend to<br />

become celebrities, much like Robert Capa, Roger Fenton, and<br />

Matthew Brady, and because <strong>of</strong> that their work takes on additional<br />

meanings. For example, despite Capa’s role as a war photographer,<br />

and his supposed neutrality <strong>of</strong> representation, he and his partner,<br />

according to Randy Kennedy in <strong>The</strong> Capa Cache, “made no<br />

pretense <strong>of</strong> journalistic detachment during the war — they were<br />

Communist partisans <strong>of</strong> the loyalist cause.” To maintain control<br />

over the lives that war photographs take after their publication, it<br />

becomes imperative to control the lives their photographers take on.<br />

By removing the human origin <strong>of</strong> the photograph, however, and by<br />

releasing it through press releases and channels, war photography<br />

becomes the state’s means <strong>of</strong> controlling the narrative.<br />

THE ICONOGRAPHY OF HOWITZERS & LARGE<br />

GUNS<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> the most iconic images that came from the Kargil <strong>War</strong> were<br />

those <strong>of</strong> the Swedish-made B<strong>of</strong>ors howitzers. According to defence<br />

analysts, the B<strong>of</strong>ors Howitzers and larger guns gave the Indian army<br />

“an edge over the Pakistanis” that would not have been conceivable<br />

previously. <strong>The</strong>se howitzers captured the imagination <strong>of</strong> the public,<br />

35

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

and a significant part <strong>of</strong> surviving Kargil war photography reflects<br />

them.<br />

SOLDIERS OF THE INDIAN ARMY AIM A 23MM ZSU-23-2 AA GUN AT<br />

PAKISTAN OCCUPIED PEAKS IN KARGIL-DRAS REGION OF KASHMIR AS A<br />

CONVOY OF TRUCKS PASSES THROUGH THE NATIONAL HIGHWAY IA,<br />

CONNECTING SRINAGAR & LEH./ UNKNOWN<br />

In the photograph above, from an unknown source, soldiers can be<br />

seen aiming a B<strong>of</strong>ors Howitzer at Pakistan-controlled peaks. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

face the only road that connects Leh to Srinagar. What makes this<br />

photograph particularly remarkable is the way perspective lines<br />

converge towards the barrel <strong>of</strong> the gun, from the top and the bottom<br />

<strong>of</strong> the frame. <strong>The</strong> mountains cradle the silencers <strong>of</strong> the doublebarrelled<br />

howitzer, indicating a level <strong>of</strong> comfort in the positioning<br />

<strong>of</strong> the gun, and obscuring any indication <strong>of</strong> the ‘rush <strong>of</strong> war.’ <strong>The</strong><br />

overall atmosphere <strong>of</strong> the photography is calm, almost serene, which<br />

makes it compelling. <strong>The</strong> juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> two nations embroiled in<br />

a vicious, high altitude war, is powerful. <strong>The</strong> well-synchronised<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> the movement and the upright posture <strong>of</strong> the jawans<br />

36

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

reinforces the myth <strong>of</strong> a nation heading to war, leading the viewer<br />

to accept the construct <strong>of</strong> righteous and just war.<br />

<strong>The</strong> photographer’s decision to include both sky and water<br />

emphasises Indian air and naval superiority. <strong>The</strong> depiction <strong>of</strong> a wide<br />

range <strong>of</strong> terrain reinforces the illusion <strong>of</strong> superiority that the<br />

photograph is intended to create, suggesting that the plethora <strong>of</strong><br />

armed forces were ready to fight wherever they needed to. <strong>The</strong><br />

photograph distinctly shows all lines <strong>of</strong> sight, from the trucks to the<br />

guns, converge onto mountains, symbolising the aim <strong>of</strong> the Kargil<br />

<strong>War</strong>, which was to recapture the peaks that were taken over by<br />

Pakistan during the winter.<br />

THE SOLDIERS<br />

Despite significant advancements in technology, the Kargil <strong>War</strong> was<br />

still fought using age-old tactics. One <strong>of</strong> the most crucial weapons<br />

in India’s arsenal was the wide array <strong>of</strong> soldiers who were able to<br />

acclimatise and fight a high-altitude war on such short notice, and<br />

despite knowing that the Pakistani soldiers had the physical higher<br />

ground. Some estimates suggest that for every Pakistani soldier in a<br />

high altitude bunker, at least six Indian soldiers were needed.<br />

Soldiers from the Indian Army and paramilitary forces like the<br />

Border Security Force (BSF) and Rashtriya Rifles (RR) contributed<br />

to an overwhelming majority <strong>of</strong> boots on the ground.<br />

37

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

IMAGE: MUSLIM SOLDIERS OF THE INDIAN ARMED FORCES OFFERING<br />

THEIR NAMAAZ (PRAYERS) BEFORE MANNING THEIR POSITION AT A BATTERY<br />

OF AUTOMATIC AND SEMI-AUTOMATIC MACHINE GUNS./ UNKNOWN<br />

<strong>The</strong> photograph above depicts three Muslim soldiers <strong>of</strong> an unknown<br />

unit <strong>of</strong> the Indian Armed Forces <strong>of</strong>fering prayers during a break in<br />

battle. This photograph is particularly iconic, for it has significant<br />

propaganda value for the Indian government. Pakistan was set up as<br />

a purely Islamic state, according to its founder, Mohammed Ali<br />

Jinnah because he felt that Muslims had no place in India. However,<br />

India is a secular country, and this image subverts the narrative<br />

championed by the Pakistani government, which is that <strong>of</strong> a small<br />

Muslim state being subdued and standing up to a Hindu aggressor.<br />

<strong>The</strong> photographer also crafts into this photograph the motif <strong>of</strong><br />

headgear to further subvert the Pakistani master narrative,<br />

progressing from a full helmet to an army green baseball cap. <strong>The</strong><br />

range <strong>of</strong> headgear shown in this image is reflective <strong>of</strong> the diversity<br />

38

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> the soldiers, suggesting that while they may all be Muslim, they<br />

are possibly from different parts <strong>of</strong> country and belong to a diverse<br />

range <strong>of</strong> religious sects. (At this time, it becomes imperative to<br />

differentiate between the government <strong>of</strong> Pakistan and the average<br />

citizen <strong>of</strong> Pakistan- the former wages war, the latter does not, and<br />

this is reflected in the prevailing narrative) <strong>The</strong> <strong>of</strong>fering <strong>of</strong> namaz<br />

also has high symbolic value, for it could also be construed as praying<br />

to the divination <strong>of</strong> the nation, Bharat Mata, for success in battle.<br />

<strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> religious symbols in war always creates for tantalising<br />

imagery because it presents the actions in a divine light, and as a<br />

result <strong>of</strong> divine intervention.<br />

T<br />

DECONSTRUCTING THE IMAGES<br />

hese two images are part <strong>of</strong> a timeless collection <strong>of</strong> images from<br />

Indian war photography, because their appeal is grounded not<br />

in specificites, but in heavy symbolism. <strong>The</strong>y are able to take on<br />

double lives through their use <strong>of</strong> symbols <strong>of</strong> strength, that enable use<br />

to craft myths around them. Like Robert Capa’s <strong>The</strong> Falling Soldier,<br />

these images represent a larger, intangible idea that feeds into the<br />

myth being propagated.<br />

<strong>The</strong> projection <strong>of</strong> force that takes place in the first image is part <strong>of</strong><br />

the ‘strong India’ narrative that is being pushed forward by all<br />

segments <strong>of</strong> the government. India has not had an anti-war<br />

government since the time <strong>of</strong> Nehru, and appeasement isn’t<br />

currently on the agenda either. By suggesting a hegemony and<br />

armed superiority over the land, the water, and the sky, the image<br />

feeds into a toxic narrative that has the potential to (and possibly<br />

intention to) mislead.<br />

In the photograph <strong>of</strong> the soldiers, by not anchoring it in the<br />

particularity <strong>of</strong> the war, the photographer creates the myth <strong>of</strong><br />

communal and religious harmony, while attempting to subvert the<br />

39

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

classical Pakistani government narrative and premise for creation <strong>of</strong><br />

Pakistan. It glosses over a bloody history <strong>of</strong> sectarian and religious<br />

violence, perpetrated largely due to religion, and removes evidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> the un-secular nature <strong>of</strong> a large section <strong>of</strong> Indian law. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong><br />

religion to subvert another religious narrative seems to be odd, for<br />

the argument seems to be an antithesis.<br />

However, in this reading <strong>of</strong> Indian war photography during the<br />

Kargil <strong>War</strong>, one thing is certain for me. Compared to the vast<br />

repertoire <strong>of</strong> works produced by Mathew Brady, Robert Capa, James<br />

Nachtwey, and other Western war photographers, aesthetically, the<br />

images that I looked at simply were unable to match the complexity<br />

and the artistic nature <strong>of</strong> the Western canon.<br />

<strong>The</strong> sanitisation <strong>of</strong> the true nature <strong>of</strong> war is highly problematic in<br />

these images. <strong>The</strong>re is no mention <strong>of</strong> more than a thousand people<br />

who died on both sides, and the two thousand who were wounded<br />

physically. <strong>The</strong>se images show a fragment <strong>of</strong> the truth <strong>of</strong> war, but<br />

not the entirety <strong>of</strong> the truth. While it may never be truly possible to<br />

capture what war is, and what it means, photography has a truth<br />

value that is ascribed to it, and therefore in most contemporary<br />

conflict situations in India, guides what a large part <strong>of</strong> the public<br />

perceives to be the sole existing truth. <strong>The</strong>se photographs are simply<br />

pieces <strong>of</strong> propaganda, a publicity exercise by the government to<br />

drum up support for a costly war.<br />

--<br />

Ishaan Jajodia<br />

<strong>The</strong> provenance <strong>of</strong> the images in this article is unknown, despite<br />

considerable research. <strong>The</strong> author and publisher intend to correct this at<br />

the earliest, and if you have any information about it, we request you to<br />

email us at info@themumbaiartcollective.com.<br />

40

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

41

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Bard From <strong>The</strong> Valley<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

R<br />

amneek Singh is a spoken word poet from Jammu. Through<br />

his poetry, he tells us stories <strong>of</strong> his home. His poems reflect<br />

on the implications <strong>of</strong> the territorial conflict between India<br />

and Pakistan over Kashmir dating back to 1947, and the atrocities<br />

that the Indian Armed forces have committed in<br />

Kashmir. Ramneek’s poem called Jhelum is based on one such<br />

mysterious disappearance <strong>of</strong> a Kashmiri friend. It’s about how he is<br />

trapped with a sense <strong>of</strong> guilt when it comes to breaking the news <strong>of</strong><br />

his loss to his friend’s family members.<br />

Every time he tries to write a poem about love, partition or conflict<br />

intervenes. It transforms the fabric <strong>of</strong> each poem. After all, “conflict<br />

gives birth to poetry”, he says. One <strong>of</strong> the biggest conflicts that an<br />

artist has to face against the world is to maintain a sense <strong>of</strong> identity.<br />

When he first shifted to Mumbai, he felt a little discouraged about<br />

42

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

getting into the poetry scene. Most <strong>of</strong> the spoken word poems in<br />

English were well received and appreciated but he had to carve a<br />

niche for Hindi poems. He had assumed poems performed in Hindi<br />

would not be as popular as in English, but his contemporaries were<br />

welcoming and encouraging which inspired him to keep at it. His<br />

intention <strong>of</strong> writing poems was not to impart knowledge but his way<br />

<strong>of</strong> sharing his pain with the world and wondering if it is capable to<br />

feeling too. One <strong>of</strong> the most significant ways in which his poems<br />

have contributed to his artistry is by providing him with an<br />

opportunity to empathize with people. One <strong>of</strong> his struggles is to<br />

recover after a poem becomes popular, to be able to compete with<br />

his own poems is a task.<br />

His poem Rhinchin and Dolma reveals the callousness <strong>of</strong> tourists and<br />

photographers who come to Kashmir to capture its beauty<br />

completely oblivious to the plight <strong>of</strong> the locals in Kashmir and their<br />

fight for freedom and sustenance. People say that words are<br />

powerful enough to change the world. Ramneek feels that through<br />

his words he can evoke the grief <strong>of</strong> those families who have lost<br />

members due to the attack on civilians in Kashmir. <strong>The</strong> pain <strong>of</strong><br />

migration when one loses what used to be their home. Through his<br />

poems he intends to show the beauty <strong>of</strong> coexistence without letting<br />

differences cause animosity. “It’s problematic when people refer to<br />

Kashmir as Kashmir without sparing a single thought for the<br />

Kashmiris who reside there!”<br />

His recent poem ‘Acche Din’ on Kashmir is about a little girl who<br />

has a disability and doesn’t understand the grave consequences <strong>of</strong><br />

living as a person with disability in a territory that is constantly under<br />

threat. Her grandfather keeps writing letters to the Prime Minister<br />

asking him to stop this fight over a piece <strong>of</strong> land. He writes:<br />

43

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2017</strong><br />

ज़मीन का टु कड़ा ह+ तो है,<br />

फ़ौज परेशान, लोग परेशान<br />

आप परेशान हम परेशान<br />

करवा देतेह; दो

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Process</strong><br />

“काँगड़ा कK पहाLड़यN के बीचो बीच<br />

जAनतN के ज़ायके<br />

कु छ ऐसे सुनाई देतेह;<br />

थुSपा,<br />

TतंVमो,<br />