Viva Brighton Issue #51 May 2017

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CLASSICAL<br />

....................................<br />

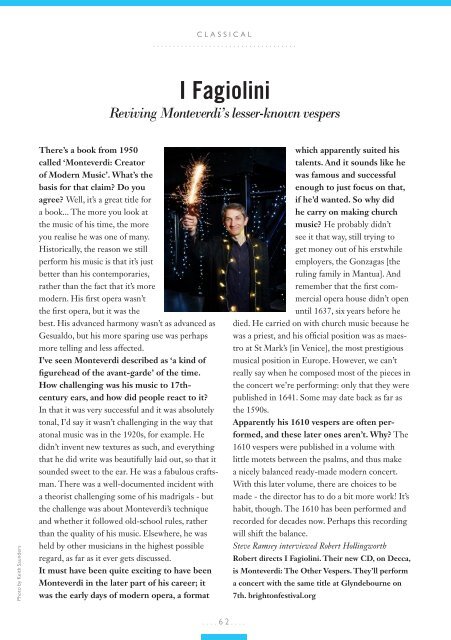

I Fagiolini<br />

Reviving Monteverdi’s lesser-known vespers<br />

Photo by Keith Saunders<br />

There’s a book from 1950<br />

called ‘Monteverdi: Creator<br />

of Modern Music’. What’s the<br />

basis for that claim? Do you<br />

agree? Well, it’s a great title for<br />

a book... The more you look at<br />

the music of his time, the more<br />

you realise he was one of many.<br />

Historically, the reason we still<br />

perform his music is that it’s just<br />

better than his contemporaries,<br />

rather than the fact that it’s more<br />

modern. His first opera wasn’t<br />

the first opera, but it was the<br />

best. His advanced harmony wasn’t as advanced as<br />

Gesualdo, but his more sparing use was perhaps<br />

more telling and less affected.<br />

I’ve seen Monteverdi described as ‘a kind of<br />

figurehead of the avant-garde’ of the time.<br />

How challenging was his music to 17thcentury<br />

ears, and how did people react to it?<br />

In that it was very successful and it was absolutely<br />

tonal, I’d say it wasn’t challenging in the way that<br />

atonal music was in the 1920s, for example. He<br />

didn’t invent new textures as such, and everything<br />

that he did write was beautifully laid out, so that it<br />

sounded sweet to the ear. He was a fabulous craftsman.<br />

There was a well-documented incident with<br />

a theorist challenging some of his madrigals - but<br />

the challenge was about Monteverdi’s technique<br />

and whether it followed old-school rules, rather<br />

than the quality of his music. Elsewhere, he was<br />

held by other musicians in the highest possible<br />

regard, as far as it ever gets discussed.<br />

It must have been quite exciting to have been<br />

Monteverdi in the later part of his career; it<br />

was the early days of modern opera, a format<br />

which apparently suited his<br />

talents. And it sounds like he<br />

was famous and successful<br />

enough to just focus on that,<br />

if he’d wanted. So why did<br />

he carry on making church<br />

music? He probably didn’t<br />

see it that way, still trying to<br />

get money out of his erstwhile<br />

employers, the Gonzagas [the<br />

ruling family in Mantua]. And<br />

remember that the first commercial<br />

opera house didn’t open<br />

until 1637, six years before he<br />

died. He carried on with church music because he<br />

was a priest, and his official position was as maestro<br />

at St Mark’s [in Venice], the most prestigious<br />

musical position in Europe. However, we can’t<br />

really say when he composed most of the pieces in<br />

the concert we’re performing: only that they were<br />

published in 1641. Some may date back as far as<br />

the 1590s.<br />

Apparently his 1610 vespers are often performed,<br />

and these later ones aren’t. Why? The<br />

1610 vespers were published in a volume with<br />

little motets between the psalms, and thus make<br />

a nicely balanced ready-made modern concert.<br />

With this later volume, there are choices to be<br />

made - the director has to do a bit more work! It’s<br />

habit, though. The 1610 has been performed and<br />

recorded for decades now. Perhaps this recording<br />

will shift the balance.<br />

Steve Ramsey interviewed Robert Hollingworth<br />

Robert directs I Fagiolini. Their new CD, on Decca,<br />

is Monteverdi: The Other Vespers. They’ll perform<br />

a concert with the same title at Glyndebourne on<br />

7th. brightonfestival.org<br />

....62....