You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

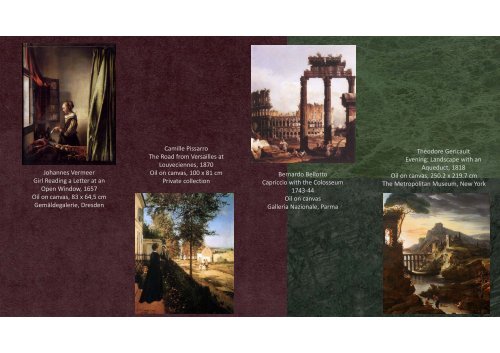

Johannes Vermeer<br />

Girl Reading a Letter at an<br />

Open Window, 1657<br />

Oil on canvas, 83 x 64,5 cm<br />

Gemäldegalerie, Dresden<br />

Camille Pissarro<br />

The Road from Versailles at<br />

Louveciennes, 1870<br />

Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm<br />

Private collection<br />

Bernardo Bellotto<br />

Capriccio with the Colosseum<br />

1743‐44<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

Galleria Nazionale, Parma<br />

Théodore Gericault<br />

Evening: Landscape with an<br />

Aqueduct, 1818<br />

Oil on canvas, 250.2 x 219.7 cm<br />

The Metropolitan Museum, New York

Claude Monet<br />

Sunrise, 1872<br />

Oil on canvas, 48 x 63 cm<br />

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris<br />

Bernardo Bellotto<br />

Liechtenstein Garden Palace in Vienna.<br />

1759‐60<br />

Oil on canvas, 100 x 160 cm<br />

Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna<br />

Johannes Vermeer<br />

View of Delft, 1659‐60<br />

Oil on canvas, 97 x 116 cm<br />

Mauritshuis, The Hague<br />

Pierre‐Auguste Renoir<br />

Dance in the Moulin de la<br />

Galette,1876<br />

Oil on canvas, 131 x 175 cm<br />

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

How has Vermeer,<br />

Canaletto and Turner<br />

depicted the<br />

importance of sunlight<br />

in numerous

After careful research and consideration, I have narrowed my decision<br />

down to the theme of Sun for my museum exhibition. My reasoning’s<br />

behind this theme is because sun is projected in majority of mediums<br />

covering drawing, paintings, and architecture. It is a natural source that<br />

has been present since the beginning of time and used daily by<br />

everything. With the sun having such a strong impact on everything<br />

around us, including ourselves, I intend to investigate the use of this<br />

source and how it has influenced and been portrayed onto art<br />

throughout the centuries.<br />

In this investigation of analysis I will include a variety of art consisting<br />

the subject of Sun with the intentions of making an exhibition.<br />

To conclude my research I will keep a biography of the evidence behind<br />

the analysis, using primary sources as well as newspapers, museums,<br />

articles, documentaries, books, and the internet in general (avoiding<br />

unreliable sources). With this information, I could then develop a<br />

suitable poster helping with its visual appearance, targeted audience,<br />

and location for the exhibition. Further detail into this exhibition, I will<br />

discover how Johannes Vermeer, Canaletto and Turner depicted the<br />

importance of sunlight in numerous paintings.<br />

Beginning with Vermeer, he was present during the<br />

Dutch Golden Period. The Dutch Golden Age<br />

spanned the 17th century, in which<br />

Dutch trade, science, military, and art were among<br />

the most acclaimed in the world. In 1568, the Seven<br />

Provinces that later signed the Union of Utrecht,<br />

started a rebellion against Philip II of Spain that led<br />

to the Eighty Years' War. The War ended in 1648.<br />

The Golden Age continued during the Dutch<br />

Republic until the end of the century.<br />

Although Dutch painting comes in the general<br />

European period of Baroque painting, and shows<br />

many of its features that lacks the idealization and<br />

Baroque work. The period is best known for<br />

reflecting the traditions of realism which was<br />

inherited from Early Netherlandish painting.

Johannes Vermeer was a 17 th century<br />

Baroque, Flemish Dutch painter, born on 31st<br />

October 1632, in the southern part of the<br />

Netherlands, Delft. He was a son to Reijnier<br />

Janszoon and Digna Baltens, who were<br />

middle‐class innkeepers and silk weavers, but<br />

for an unknown reason they had changed his<br />

surname to Vermeer. His father associated<br />

with the Guild of St. Luke where he traded and<br />

sold various paintings. This is suggested where<br />

Vermeer’s art profession had begun. His early<br />

years, being apprenticed under artists like<br />

Leonart Bramer, Vermeer produced many<br />

biblical and mythological paintings but then<br />

gradually favouring everyday life scenes in his<br />

later works. Vermeer married Catherine,<br />

having 15 children in total. He supposedly died<br />

of a stroke on 16 th December 1675, leaving the<br />

family in debt.<br />

Delft during this period was an extremely<br />

traditional Catholic and Protestant province that<br />

was continuously being invaded by Spanish<br />

troops, affecting the economy and art market.<br />

This had added to Vermeer's debt as he only<br />

searched for local commissions which was<br />

unusual for an artist of this time. He focused on<br />

chiaroscuro, producing around 35 pieces of art,<br />

where he found patronage by a single Delft man<br />

named Pieter Van Ruijven.<br />

The Procuress (detail<br />

of a self portrait?)<br />

Johannes Vermeer<br />

1656<br />

Oil on canvas, 143 x<br />

130 cm.<br />

Gemäldegalerie Alte<br />

Meister, Dresden

The term 'camera obscura' translates into 'dark chamber',<br />

as its most basic form was a dark room, windows<br />

shuttered, with a small hole on one wall. This method uses<br />

the sun to portray outlines onto a canvas to give accurate<br />

perspectives of what your trying to reveal. Once the light<br />

enters the room through the hole, the image outside is<br />

transposed invertedly onto the opposite wall. The light<br />

travels in a straight line also known as rectilinear<br />

propagation of light. The size of the hole influences the<br />

image as a small hole creates a sharp but dim image and a<br />

larger hole produces a brighter picture but less focused,<br />

with the sun only being clearly visible.<br />

It is suggested that Johannes Vermeer was<br />

the pioneer of a method called camera<br />

obscura. It is not certain that Vermeer used<br />

camera obscura but the evidence and<br />

layout of his composition has led many to<br />

believe that he used this technique in his<br />

later works as an aid for his painting. The<br />

camera obscura was the prototype of the<br />

photographic camera, but without the lightsensitive<br />

film or plate.<br />

Camera obscura changed around the mid‐<br />

16th century after a man called Cardano<br />

replaced the pinhole with a lens, which was<br />

described in his book “De Substilitate Libri.<br />

This increased the brightness and image size.<br />

You could focus the image by moving the lens<br />

or the viewing surface.

A few convincing points were found in the visual qualities<br />

produced by Vermeer in his paintings to support the argument<br />

he used camera obscura.<br />

Variations principal planes of focus;<br />

precise diminution of ++;<br />

halation of highlights;<br />

precise treatment of reflections;<br />

closeness of the point of view to the window wall;<br />

precise convergence of parallel lines located in a plane<br />

perpendicular to the viewing axis;<br />

use of curtains to darken viewing room and control subject<br />

illumination;<br />

relative detail in still life portion versus figure detail;<br />

consistent proportions of the paintings (4‐5:5 or almost<br />

square);<br />

dimensional precision in rendering objects.<br />

It is suggested Vermeer used this method on the<br />

“View of Delft”. This oil painting was painted on<br />

canvas around 1659‐60, measuring 97cm x 116cm,<br />

which is now placed in Mauritshuis, The Hague. The<br />

painting was always labelled as his masterpiece and<br />

the most famous cityscape of the Dutch Golden Age,<br />

which covered majority of the 17th century. It was<br />

sold for the upmost amount of 200 guilders in the<br />

1696 auction of Dissius’s 21 Vermeer. The Mauritshuis<br />

bought it in 1822 for 2,900 guilders by the Dutch King,<br />

Willem I.

It is considered Vermeer painted the View of Delft<br />

in his home demonstrated on the image below.<br />

A photograph taken by Adelheid Rech of present day where<br />

Vermeer would have taken the painting.<br />

The painting has been divided into four horizontal<br />

groups: the quay, the water, the town, and the<br />

sky. He portrays an early morning with a blue sky<br />

along with a few dark clouds. The sky has just<br />

cleared up after a sudden bout of rain. Under<br />

these clouds, a shaft of sunlight touches the roofs<br />

of Vermeer’s landscape of Delft. The chiaroscuro<br />

of the buildings by one another creates a sense of<br />

depth as highlighted buildings creating shadowy<br />

surroundings.

About 15 figures are portrayed in this painting. The<br />

seven figures in the foreground signify Dutch society<br />

during the 17th century. Vermeer prided himself on<br />

portraying figures in their daily life as Delft was under<br />

Spanish rule so most paintings had to depict images of<br />

domesticity and the local surroundings with Christian<br />

morals and values. He portrays a mother with a child,<br />

men and two peasant women all wearing traditional<br />

clothing. They represent the idealism of Delft<br />

community during the peak of its working society. The<br />

three men where fashionable attire and the other<br />

figures wear peasant garment of black skirts and jackets<br />

with white collars. Vermeer had painted out a figure that<br />

stood to the right of the two‐peasant woman.<br />

Most of the town is shadowed apart from the<br />

central tower, the Nieuwe Kerk Church. The<br />

church has been emphasised by sunlight<br />

making it the cities symbolic core.

On the right of the painting,<br />

Vermeer depicts the Rotterdam<br />

Gate and above it is the main<br />

building with the barbican and<br />

twin towers. The building is<br />

shaded in front as the sun is<br />

coming from behind. Although,<br />

there are bright patches of sun,<br />

which is evidently above the<br />

gate. This identifies the light<br />

sourced and positioning of the<br />

clouds. The dramatic morning<br />

sky takes up over half of the<br />

picture which adds the illusion of<br />

a breezy climate. The patchiness<br />

of the shadows creates a<br />

baroque style which Vermeer<br />

was very fond of.<br />

In front is a double draw‐bridge shows a few<br />

small shipyards alongside the Schie canal.<br />

Smaller boats increased in the 17th century for<br />

the use of trade, specifically designed for the<br />

herring fishery. On these shipyards, faded<br />

figures are portrayed in the background and<br />

alongside the back wall.

This building is Schiedam Gate.<br />

Again, it had been shadowed using<br />

tints of white to highlight the<br />

corners to make the building seem<br />

three‐dimensional. The tiny clock<br />

shows it’s just past 7 o’clock, which<br />

gives the viewer a hint at the time<br />

of day it is. The buildings are made<br />

of red brick with a layer of<br />

limestone. The red brick was an<br />

affordable resource but the<br />

limestone was expensive and most<br />

likely imported.<br />

Behind the main gate building on the<br />

left, you can just about see the<br />

Armamentarium, also known as the<br />

weapons warehouse, that still stands<br />

today. This building was for storing<br />

large wooden material like planks,<br />

beams, grain mills on carts and<br />

battering rams, for warfare use.

This section of water is part of the River Schie that flows into the<br />

Rhine of Schiedam, near Rotterdam. This part of the river has a<br />

triangular form which had been in widened in 1614 that aided the<br />

harbour of Delft. Vermeer portrays a clear river with precise<br />

ripples on the water. The placing of light and shadow from these<br />

buildings above help predict the time this image was painted and<br />

helps define the cities distance. Thin strokes of brown‐grey and<br />

grey‐blue paint show reflection on the water and these are<br />

softened with a brush. Camera obscura has been used to show<br />

shimmering in the water to emphasize the shine so that each<br />

ripple could be depicted.<br />

Vermeer uses bold colours for his painting. The<br />

main colours used are lead white, yellow ochre,<br />

natural ultramarine, and madder lake. The sky is<br />

painted with a mild brown and yellow ochres to<br />

separate the clouds from the sunlight and other<br />

bold colours are used on the roof of the buildings<br />

and sunlit areas to create a deeper perspective.<br />

Vermeer mixed sand into the paint to create and<br />

uneven surface. The grainy effect gave the<br />

painting a three‐dimensional appearance.<br />

Vermeer used camera obscura in many of his oil<br />

paintings, like “The Milkmaid”, “Woman Holding<br />

her Balance”, and many more. The figures are<br />

placed in the exact same area with sunlight<br />

coming in from the left‐hand side. Vermeer has<br />

replaced a few objects and figure gestures,<br />

making the argument if he has used camera<br />

obscura or not, highly convincing.

Johannes Vermeer,<br />

Woman Holding a<br />

Balance<br />

1662‐63<br />

Oil on canvas, 42,5 x 38<br />

cm<br />

National Gallery of Art,<br />

Washington<br />

Without camera obscura, it wouldn’t be possible<br />

to create precise portraits of what you intend on<br />

revealing. A prime example of an artist from the<br />

17th century that didn’t use camera obscura is<br />

Louis de Caullery and you can see that the<br />

background of his painting is blurred. This is<br />

possibly because he was focusing on the two<br />

building in the front but it is still the view he<br />

intended on painting that would have come with<br />

great difficulty in making it accurate.<br />

Johannes Vermeer,<br />

The Milkmaid<br />

c. 1658<br />

Oil on canvas, 45,5 x 41<br />

cm<br />

Rijksmuseum,<br />

Amsterdam<br />

Louis de Caullery “A View of<br />

the Campidoglio, Rome” 17th<br />

century, oil on panel, 50 x 71<br />

cm. Private collection

Another suggest painting, along with the “View of Delft” that<br />

Vermeer most likely used camera obscura on was “Little<br />

Street”. Many locations for this image have been proposed,<br />

but the most suited location was the Vlamingstraat.<br />

Vlamingstraat was a narrow street that runs next to a canal<br />

in the centre of Delft, where Vermeer was born.<br />

The Little Street displays a mix of features, revealing painting<br />

on brick, wood, and glass, trees and sky, and portraying four<br />

figures of two women and two children.<br />

Vermeer supposedly sits in front of Old Woman’s and Old<br />

Man's Almshouse, which was directly across the street from<br />

Vermeer's home. The fact that the Delft almshouse was torn<br />

down in 1661 can be used to support the date assigned to<br />

this picture.<br />

A curator of 17th century paintings at the Rijksmuseum,<br />

Pieter Roelofs explains “The answer to the question as to the<br />

location of Vermeer’s The Little Street is of great significance,<br />

both for the way that we look at this one painting by<br />

Vermeer and for our image of Vermeer as an artist.”<br />

Johannes Vermeer<br />

The Little Street<br />

1657–1661<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

54.3 x 44 cm<br />

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam<br />

iVlamingstraat in Delft, at the<br />

point where the present‐day<br />

numbers 40 and 42 stand.

Vermeer uses thee clouds that<br />

are achieved with gentle but<br />

rapid diagonal brushstrokes of<br />

white with red ochre and blue<br />

azurite. Blue azurite was the<br />

most common blue found on<br />

the palette of 17th‐century<br />

Dutch painters, also used on<br />

the “View of Delft”.<br />

Grape vines are in a variety of<br />

Dutch cityscapes. However,<br />

Dutch grapes failed to produce<br />

drinkable wine because there<br />

was often little sunlight, so<br />

instead, used for a decorative<br />

effect. Vines have symbolized<br />

loyalty and marriage or<br />

domestic virtue but there is no<br />

evidence Vermeer made this<br />

link.<br />

He gives the illusion of a sunlit<br />

day. By adding clouds, he could<br />

emphasize on chiaroscuro<br />

within his portrait of the “Little<br />

Street”.<br />

Rows of worn cobblestones create a sense of depth.<br />

Soapy water streams down from the servants wash<br />

basin into a gutter, which runs along the wall<br />

dividing the properties of the doorways. The water<br />

then flowed into a canal below just out of view.

Vermeer depicted a house<br />

which dates from the late<br />

15th, or the beginning of the<br />

16th century. The house had<br />

tall ceilings, well‐lit rooms and<br />

unusual step‐gables making it<br />

one of the surviving medieval<br />

houses of the time.<br />

The house was saved by the<br />

Great Fire in 1536 which had<br />

destroyed a vast amount of<br />

Delft. It shows repainting and<br />

crack patches that may have<br />

been caused by another civic<br />

tragedy, which was the<br />

Thunderclap in 1654.<br />

Little Street remains the most naturalistic<br />

interpretations of a 17th‐century Dutch cityscape.<br />

The finished image shares topographic tradition of<br />

current landscape painting.<br />

The main building is unusually off‐centre and<br />

cropped off on the top, which encourages the<br />

sense of a close‐up, almost like a photograph,<br />

adding to the evidence of camera obscura. It is<br />

unlikely that it had been regarded as a memorial<br />

"portrait" of a specific house.<br />

Vermeer's signatureis<br />

imprinted above the<br />

rustic benches placed<br />

on the left of the<br />

canvas.<br />

An ammunitions magazine exploded killing hundreds of citizens<br />

and homes.

A fully‐clothed maid is portrayed<br />

washing laundry over a wooden<br />

barrel at the end of the private<br />

alleyway.<br />

A broom stands close to the<br />

figure. In the 17th century,<br />

sweeping and booms had strong<br />

relations with cleanliness and<br />

purity. The thought of domestic<br />

virtue was important to the<br />

Christendom and Dutch nation,<br />

hence why Vermeer painted the<br />

working life of citizens.<br />

Vermeer had initially painted a<br />

seated woman doing handiwork<br />

at the entrance of the alleyway. She was taken out as she was<br />

likely to be obstructing the passageway, effecting the three<br />

dimensionality.<br />

A boy and a girl are<br />

portrayed playing, facing<br />

away and dressed as<br />

miniature adults. By<br />

turning away from the<br />

viewer, Vermeer<br />

motivates us to explore<br />

the thoughts and<br />

emotions of his own<br />

childhood.<br />

The elderly woman is<br />

seen doing<br />

needlework, possibly<br />

sewing, judging by<br />

the large piece of<br />

clothe on her lap.<br />

Sewing was an<br />

attribute of domestic<br />

virtue of Biblical<br />

origin.

Vermeer was ahead of his time for his cityscapes from<br />

the help of the sun. The sun helped Vermeer to<br />

navigate the right proportions of buildings distances,<br />

layout, and figure proportions. It allowed Vermeer to<br />

use the sun to see where the reflections and shadows<br />

will fall, creating a three‐dimensional, dynamic<br />

illusion.<br />

Théophile Thoré‐Bürger<br />

Date taken – unknown,<br />

Author – unknown<br />

Many thought camera obscura wasn’t a talent as the<br />

picture was already there for you to paint, like<br />

tracing, but this technique had helped to advance in<br />

many aspects for things we use today. It has<br />

advanced portraiture and even make it come to ‘life’<br />

through films. This all resulted with making him a<br />

master of Dutch painting and forever inspiring<br />

continuing artists like Théophile Thoré who aimed to<br />

rediscover Vermeer and the artist Giovanni Antonio<br />

Canal, better known as Canaletto.<br />

Antonio Visenti<br />

Portrait of Giovanni Antonio<br />

Canal, called Canaletto<br />

before 1735<br />

Engraving<br />

Royal Collection, Windsor

An 18 th century artist named Giovanni Antonio Canal, better known<br />

as Canaletto meaning “Little Canal”. He was a Rococo painter that<br />

was highly inspired by Vermeer and suggestively used the same<br />

technique as the Dutch master himself. Canaletto was born on 28 th<br />

October 1697 in Venice where he admired and depicted views of<br />

the city of Venice. He was a son to Bernardo Canal and Artemisia<br />

Barbieri. He began an occupation in his father’s steps as a theatrical<br />

scene painter.<br />

On his return from Rome in 1719, he began painting his well‐known<br />

topographical paintings which were said to be formed with the use<br />

of camera obscura for accuracy, under the training of the older Luca<br />

Carlevaris. Carlevaris was famous for his urban cityscapes.<br />

Canaletto's early artwork was painted 'from nature'. Majority of his<br />

later works tend to have distant figures, painted as blobs of colour.<br />

This was an effect formed by using a camera obscura because it<br />

blurred object further away.<br />

English collectors, on their Grand Tour, admired Canaletto’s artwork<br />

and often commissioned them through the agency of the merchant<br />

Joseph Smith. In 1739. Britain declared war on Spain and the 'War<br />

of Jenkins's Ear' began. This began after repeated depredations on<br />

British ships by Spanish 'guarda costas'. This was mainly a colonial<br />

war in Caribbean waters. It was named after a<br />

Captain Robert Jenkins. Britain declared war on<br />

Spain whose ear had been severed by the Spanish.<br />

The War lasted until 1748, but the war formed into<br />

a larger war called the Austrian Succession, which<br />

took place from October 1740 until October 1748.<br />

This war reduced Canaletto’s commissions greatly<br />

as it was too risky associating with the British.<br />

After his return to Venice, Canaletto was elected to<br />

the Venetian Academy in 1763. In his later works,<br />

he often worked from old sketches and continued<br />

painting until his death in 1768, successfully<br />

teaching his pupils; Bernardo Bellotto, Francesco<br />

Guardi, Michele Marieschi, Gabriele Bella,<br />

Giuseppe Moretti, and Giuseppe Bernardino Bison.

Canaletto often produced pictures that were above street level<br />

and not always portraying houses where they should be. Above<br />

ground level gives a clue as to how the views were found. The<br />

person commissioning a painting would have wanted a view from<br />

the main room of their house and that room was almost always on<br />

the first floor.<br />

Antonio Visenti<br />

Portrait of Giovanni<br />

Antonio Canal, called<br />

Canaletto<br />

before 1735<br />

Engraving<br />

Royal Collection, Windsor<br />

Cityscape painting of his is the “View of the Bacino di San Marco (St Mark’s Basin)”.<br />

Painted between 1730‐35. Oil on canvas 54cm x 71cm, placed in Pinacoteca di Brera,<br />

Milan<br />

Canaletto used the camera obscura method, the sun<br />

being the main resource. By putting curtains over the<br />

windows in front of the view of Bacino di San Marco,<br />

he would then make a small hole within one curtain.<br />

He then placed a lens or lenses in this hole. The<br />

sunlight then projected an upside‐down image onto a<br />

canvas or a sheet of paper, which Canaletto used a<br />

lot. This was a very similar method to Vermeer but<br />

Canaletto had access to a lens which made the made<br />

the image more precise and easier to form.

Canaletto produces a rococo approach to the layout of this scene,<br />

which was inherited from the Grand Tour from classical buildings and<br />

strong baroque shading. Every object observed from reality but<br />

arranged in an almost geometric sequence. The painting depicts a<br />

highly dynamical balance marked by a complex "choral" harmony<br />

which reveals its true nature. He did this by applying theoretical<br />

perspective to an object to simulate another, he rediscovered an<br />

object's natural perspective. He celebrates the height of Venice’s by<br />

portraying the working lives under a blue sky.<br />

completed in 1450. Canaletto manages to create a<br />

replica portraying smooth repetition and a<br />

harmonious design. In comparison to his English<br />

grey ground paintings, he uses soft traditional<br />

Venetian colours in the overall canvas, which were<br />

warm reds, orange, and tones of brown as you can<br />

see in the Palazzo Ducale. He creates Gothic,<br />

Moorish, and Renaissance architecture<br />

characteristics.<br />

Canaletto has portrayed a scene from Piazza San Marco, also known<br />

as St Mark’s Square. This building is Palazzo Ducale, or Doges Palace<br />

which was built in two parts. The eastern wing, which faces the Rio di<br />

Palazzo, was built between 1301 and 1340. The western wing, facing<br />

the Piazetta San Marco, took an additional 110 years to build and was<br />

First digital image by Roxane Sperber. Giovanni Antonio Canal<br />

(Canaletto), Cross‐section from an area of green trees on the horizon,<br />

Venice: the Piazzetta towards S. Giorgio Maggiore, ca. 1724, oil on<br />

canvas, 173.0 x 134.3 cm<br />

Second digital image by Roxane Sperber. Giovanni Antonio Canal<br />

(Canaletto), Cross‐section from area of water with wave,<br />

Westminster Bridge, with the Lord Mayor’s Procession on the,<br />

1747, oil on canvas, 95.9 x 127.6 cm, Yale Center for British Art,<br />

New Haven, Connecticut

The building is central‐right to the painting. Its structure consists of<br />

arches for doors and windows and smaller pillars holding the middle<br />

structure in the centre up. The pillars show a traditional<br />

Romanesque appearance, which was one of the main attributes to<br />

neoclassical paintings and artists on the Grand Tour.<br />

The fall of the shadows indicates that the San Marco view is shown<br />

in late morning light, while that of the Doge’s Palace is seen in the<br />

afternoon. The sun is supposedly beaming from the top left onto<br />

the building, creating shadows along the top of the building, right<br />

edge of the windows and darkness below in the arches to the doors.<br />

The use of chiaroscuro creates a sense of depth and liveliness to the<br />

urban surroundings and building, encouraging the image to come to<br />

life.<br />

In the centre, Canaletto portrays San Marco or<br />

translated into Saint Mark’s column. Placed to the left<br />

of Saint Mark is San Theodoro or other known as Saint<br />

Teodoro of Amasea, is hidden behind the building in<br />

this perspective. Saint Mark birth date is unknown. He<br />

was one of Christ's 70 disciples and the four<br />

evangelists, born in Cyrene, Libya. He travelled with<br />

Saint Barnabas and Saint Paul on religious missions,<br />

during which he founded the Church of Alexandria. He<br />

died in 68 A.D.<br />

In Alexandria, Egypt. His presence printed around<br />

Venice has become an iconic figure and the columns<br />

have become a gateway to the city. Until the mid‐<br />

18th century, where Saint Mark and Saint Teodoro<br />

have become allegorical figures for justice as<br />

criminal executions were held at the piazetta. The<br />

two columns are painted red, signifying where public<br />

executions are held. Behind the columns and Doge’s<br />

Palace, you can see the back of the cathedral of St<br />

Mark's Basilica.

On the left of the painting, Canaletto<br />

has portrayed the bell tower of St<br />

Mark's Basilica, named the San Marco<br />

Campanile. It stands above all the<br />

other buildings, making it a symbolic<br />

mark for the cityscape. It is 98.6<br />

meters tall, making it the highest<br />

tower in Venice. It was completed in<br />

1152 by the Doge Domenico<br />

Morosini.<br />

Canaletto paints the tower one colour, matching the Doges Palace,<br />

creating an orange, yellow tint. A pyramidal top caps the tower. A<br />

golden weathervane in the form of an archangel Gabriel sits at the<br />

top of the point today but the point in Canaletto’s painting has been<br />

cropped out. The campanile reached its present form in 1514. The<br />

replica still stands after lightening and earthquakes has had its toll<br />

on the structure. It had been reconstructed in 1912 after its collapse<br />

in 1902, damaging its surroundings.<br />

Canaletto faces the Venetian lagoon which was<br />

completed in the early 15th century, though portions<br />

of it were rebuilt after a fire in 1574. He includes<br />

about ten figures in the foreground and many tiny<br />

figures in the background, supporting the case of<br />

Canaletto using camera obscura.<br />

The figure on the far left has been considered to<br />

Vermeer as he paints a portrait of the city. All the<br />

other figures seem to be transporting goods. Venice is<br />

famous for their canals and Gondolas which are flatbottomed,<br />

asymmetrical Venetian rowing boats. They<br />

are well suited to the conditions of the Venetian<br />

lagoon. They have similar features to a canoe, except<br />

it is narrower. Gondolas are handmade using 8<br />

different types of wood (fir, oak, cherry, walnut, elm,<br />

mahogany, larch, and lime) and are composed of 280<br />

pieces. The oars are made of beech wood.

For centuries, the gondola was the leading use of transportation and<br />

most common watercraft within Venice, having 8‐10,000 gondolas<br />

during the 17 th and 18 th century. Their primary role today is to carry<br />

tourists on rides at fixed rates, serving as traghetti (ferries) over the<br />

Grand Canal as public transportation.<br />

Canaletto created many paintings of Venice during his lifetime, some<br />

similar to “View of the Bacino di San Marco” but with slightly<br />

different perspectives.<br />

In this painting, he has produced a wider<br />

perspective, however with different colour tones<br />

creating a more sunny appearance. The sun is<br />

beaming directly onto the view, forming little<br />

contrast and resulting with fewer shadows from<br />

the buildings. Canaletto created many similar<br />

perspectives like “Palazzo Ducale and the Piazza di<br />

San Marco”, perhaps with different weather<br />

condition which was useful for propaganda and in<br />

perfecting the perfect view.<br />

Canaletto,<br />

Palazzo Ducale and the Piazza di San Marco<br />

c. 1755<br />

Oil on canvas, 51 x 83 cm<br />

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Canaletto painted Piazza San Marco from many different<br />

angles. This painting, which was originally in the collection of<br />

Prince of Liechtenstein, is now currently displayed in California.<br />

Piazza San Marco is the official centre of Venice<br />

where throughout the centuries, tourists all around<br />

the world come and celebrate and work in the<br />

offices of the state. Canaletto creates a sense of<br />

topographical detail into his composition with the<br />

sunlight coming from the right‐hand side. It shines<br />

onto the gothic architecture.<br />

Canaletto “View of Venice with St Mark’s” c.1735. Oil on canvas 46cm x 63cm.<br />

Displayed in Huntington Art Collection, San Marino, California, USA.<br />

He portrays Doges Palace in the background on the<br />

left with a geomantic, architectural structure, which<br />

is hidden behind the Basilica Byzantine Cathedral in<br />

the foreground of the image. Although, Canaletto<br />

manages to illuminate it with sunlight, still bringing<br />

it to the surface, making it central so it is still<br />

recognised and stands‐ out from the angle of the<br />

view.

The building on the left in the foreground dominates the image. This<br />

building is Basilica di San Marco, also known as Chiesa d’Oro (The<br />

Golden Church). This church was destroyed in 976 during a rebellion<br />

against Doge Pietro Candiano IV. A second church was built in 1063 but<br />

was not consecrated until 1094, after Saint Mark’s relics, which had<br />

been lost in the years following the destruction of the first church,<br />

were rediscovered.<br />

It has distinctive white and pale‐rose pigmented marble with opulent<br />

Byzantine decoration. The front of the structure displays five large<br />

round‐arches. He paints the gilded mosaic with bright strokes in<br />

comparison to the detailed building itself. Above every arch are four<br />

horses of St Mark, looted from the Hippodrome of Constantinople in<br />

1204.<br />

Canaletto portrays the Saint Teodoro of Amasea<br />

column vaguely, like in “View of the Bacino di<br />

San Marco (St Mark's Basin)” on the right in the<br />

background. However, this time he portrays<br />

Saint Teodoro and Saint Mark’s column together.<br />

The columns draw your attention to the<br />

background. It’s capped by a lion which was the<br />

Saints evangelistic symbol.

Past the columns you can just about see the island of San Giorgio<br />

Maggiore in the lagoon beyond. Adding the lagoon reminds and helps<br />

promotes Venice’s maritime history and watery location. Canaletto had<br />

a wide range of green earth colours in Venice ranging from deep forest<br />

greens to turquoise colours. He used green‐blue pigments to paint the<br />

water of the Venetian canals. In some of Canaletto’s paintings, he had<br />

recently introduced during his time in England, a blue pigment called<br />

blue verditer that had not been previously identified in his Venetian<br />

palette. This blue replaced the green earth pigments.<br />

Canaletto lightens the image with a clear blue sky<br />

and white clouds. The clouds and blue sky<br />

indicate a hot climate. He paints the clouds quite<br />

loosely, unlike in Vermeer’s painting which was at<br />

least a century earlier. Vermeer paints fluffy and<br />

bold clouds with a prominent dark cloud that<br />

partially covers the cityscape. Canaletto was<br />

famed for his use of light. He was influenced by<br />

Vermeer, who also includes a dark cloud which<br />

covers part of the city.<br />

Vermeer. “View of Delft” Detailed<br />

view of the clouds in comparison to<br />

Canaletto’s clouds.<br />

Canaletto “View of Venice with St<br />

Mark’s” Detailed view of the clouds in<br />

comparison to Vermeer’s clouds.<br />

This shadows and restricts the sunlight greatly as he<br />

paints a contract of light and shadow on the<br />

pavement. In comparison to the foreground, he<br />

emphasises the figures shadows where the sun is<br />

beaming onto them.

The long shadows stretch across the<br />

square, forming from the right to the left,<br />

suggests it is a late afternoon as the sun is<br />

about to go into sunset.<br />

Like Vermeer, Canaletto portrays the different social classes doing<br />

everyday responsibilities and general walking around the square. He<br />

differentiates the diverse classes by what they are wearing and what<br />

they are doing. Some figures are dressed down, with beige clothing<br />

which gives the viewer the impression of a less wealthy, social status<br />

and some are wearing all black with hats, almost like a uniform –just<br />

like the characters at the front in “View of Delft”. They give the<br />

impression of some sort of importance.<br />

Canaletto depicts the importance of the sun by using it as a powerful<br />

feature in creating depth in the painting. He uses a strong contrast<br />

with a high intensity of sunlight to create shadows and reflections of<br />

the architecture, objects and people onto the canal and pavement.<br />

Unlike Vermeer, he uses smooth brushstrokes to keep a flat surface,<br />

whereas Vermeer added sand to make it standout.<br />

The smooth appearance helps create a threedimensional<br />

appearance like a photograph with<br />

the help of realistic shadows and cutting off the<br />

painting like in “View of Venice with St Mark’s” on<br />

the right‐side, which was later used by artists like<br />

Edgar Degas. Canaletto’s use of sunlight was<br />

striking. He is announced for his precision with the<br />

suggested method of camera obscura. It has been<br />

considered that he left little clues as he did not<br />

want to be accused of potential witchcraft.<br />

Years on, Canaletto helped to influence many<br />

other artists in the progression of their careers<br />

still baffled by his accuracy. Joseph Mallord<br />

William Turner was one of the main artists<br />

inspired by Canaletto’s precisions. Although,<br />

Turner didn’t use camera obscura, but his<br />

paintings were also precise, including the sun in<br />

his oil paintings and other mediums of his art,<br />

helping the enhance the portraits.

Joseph Mallord William Turner<br />

Self‐Portrait<br />

c. 1799<br />

Oil on canvas, 74 x 58 cm<br />

Tate Gallery, London<br />

Joseph Mallord William Turner was<br />

born April 1775, Maiden Lane,<br />

Covent Garden, London. His father,<br />

William Gay Turner moved to<br />

London around 1770 to follow his<br />

father’s trade, where he eventually<br />

became a barber and wig‐maker. His<br />

mother came from a line of<br />

prosperous London butchers and<br />

shopkeepers.<br />

Turner was sent to stay with uncles<br />

at Brentford in 1785 and<br />

Sunningwell in 1789, and to<br />

Margate in 1786 where he also<br />

attended school due to his mother,<br />

Mary Marshall, mental disturbance.<br />

At home his father encouraged his<br />

artistic talent. In December 1789, young Turner entered the Royal<br />

Academy Schools, where he progressed from the Plaister Academy,<br />

drawing from casts of ancient sculpture, to the life class in 1792. By<br />

1794, with his friend Thomas Girtin, he attended the evening ‘academy’<br />

accommodated by Dr Thomas Monro at his house in the Adelphi, they<br />

both studied in copying works by other artists.<br />

Landscapes and antiquarian topography were<br />

popular during this period. In the following years he<br />

advanced in the styles of the Old Masters and made<br />

rapid progression in their techniques. He was<br />

favoured by many which led to big commissions by<br />

patrons like Richard Colt Hoare, William Beckford<br />

and Duke of Bridgewater. In 1819, Turner visited<br />

Italy. The first time he travelled to Venice, Rome and<br />

Naples where he was inspired by Canaletto.<br />

His father's death in 1829 affected him and his<br />

artwork, resulting with depression. His studies<br />

showed that he was a Romantic landscape painter,<br />

watercolourist and printmaker, which were said to<br />

have laid the foundation for Impressionism due to<br />

their careless brushstrokes in some of the paintings.<br />

He died in the house of his mistress Sophia Caroline<br />

Booth in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea on 19 December<br />

1851. He was recognised as "the painter of light“.<br />

His last words were suggested to be "The sun is<br />

God" before passing away.

Turner was present during a time where European politics, philosophy,<br />

science and communications were fundamentally reoriented. It was<br />

referred to as the “Age of Reason or the “Enlightenment”. The early<br />

Enlightment began in 1685 by natural philosophers of the Scientific<br />

Revolution, including Galileo, Kepler and Leibniz. The movement<br />

increased in the high Enlightment, lasting roughly until 1815. the high<br />

Enlightment was a time of religious faith being questioned among<br />

more rational lines and deists and materialists argued that the universe<br />

seemed to determine its own course without God’s intervention. The<br />

late Enlightment led to the French Revolution of 1789. This threw out<br />

the old authorities to remake society along rational lines.<br />

The Enlightenment produced numerous books, essays, inventions,<br />

scientific discoveries, laws, wars and revolutions. The American and<br />

French Revolutions were directly inspired by Enlightenment ideals.<br />

The most influential publication of the Enlightenment was<br />

the Encyclopaedia. This was published between 1751 and 1772 in<br />

thirty‐five volumes. The publication was compiled by Denis<br />

Diderot, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and 150 scientists and philosophers<br />

who helped spread the ideas of the Enlightenment across Europe.<br />

The Enlightenment eventually resulted with the 19thcentury<br />

Romanticism. The term itself was invented in<br />

the 1840s, in England. However, the movement had<br />

been present since the late 18th century, primarily in<br />

Literature and Arts.<br />

In England, Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, and Byron<br />

characterised Romanticism. Romanticists believed<br />

that the advances made by the Enlightenment were<br />

creating an cruel, and conformist society. They<br />

believed that science and rationality could never truly<br />

understand the world and the human personality.<br />

Romanticism conflicted with "classicism," where it<br />

portrays idealistic and the goodness of<br />

the natural. Romanticism shows logic and reason<br />

cannot explain everything. In the visual arts,<br />

Romanticism appeared in landscape painting from<br />

as early as the 1760s. British artists began to turn to<br />

introduce natural catastrophes and Gothic<br />

architecture.

Turner produced many Venetian paintings during his visit to Italy in the<br />

1830’s, which were influenced by Canaletto. Canaletto not only<br />

inspired the portraiture but also the technique. They both use<br />

squiggles, dashes and dots in their artwork. His lines are energic, fluid<br />

and subtle. He was also taught different styles from artists like Piranesi,<br />

Ducros,, Loutherbourgh, and Vernet. It is believed his intentions were<br />

to gather and transform foreign techniques to produce a unique style.<br />

The paint is thickly applied and masks the weave of<br />

the canvas. The base is white with layers of gray,<br />

beige and imprimatura. Glazes and scraps are craved<br />

creating light‐colored paint that create the luminous<br />

effect. The details of architecture and rigging are<br />

accomplished with very thin fluid paint occasionally<br />

reworked by scratching in with a blunt tool. At the<br />

1834 Royal Academy show, critics gave praise to the<br />

scene’s radiant, sparkling waters.<br />

Turner devised this Venetian cityscape as a symbolic<br />

salute to commerce. It was originally painted for<br />

Painted for Henry McConnel, The Polygon, Ardwick,<br />

Manchester but now lies with The National Gallery.<br />

Joseph Mallord William Turner<br />

Venice: The Dogana and San Giorgio Maggiore, 1834<br />

oil on canvas<br />

overall: 91.5 x 122 cm<br />

Widener Collection of The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

The statue portrays two Atlases lifting a golden<br />

bronze sphere on the top of which is where Giuseppe<br />

Benoni's Fortune stands. By turning indicates the<br />

direction of the wind. The last renovation of the<br />

building was done by Alvise Pigazzi in 1838.<br />

On the right is the Punta della<br />

Dogana, topped by a statue of<br />

Fortune or Atlas. Punta della Dogana<br />

is located between the Grand and<br />

Giudecca Canals at the tip of an island<br />

in the Dorsoduro district. Adjacent<br />

to each other are the Dogana da Mar, Patriarchal Seminary, and Santa<br />

Maria della Salute. It is diagonal from the Piazza San Marco. This point<br />

was used for docking and customs as early as the beginning of the 15th<br />

century. The temporary structures built to store merchandise. The<br />

customs workers were replaced by the Punta della Dogana when it<br />

began construction in the 1670’s.<br />

The building continued to be a customs house, until<br />

the 1980s. After 20 years of abandonment, the<br />

Venice city council transformed it into a<br />

contemporary art space, designed by architect Tadao<br />

Ando. In June 2009, after 14 months of work, Punta<br />

della Dogana reopened to the public. Still today, the<br />

building has been presenting temporary exhibitions<br />

since.

Like in many of Canaletto’s Venice cityscapes, Turner copies the<br />

features of Canaletto’s paintings of granolas covering the cannels. He<br />

uses strong, bright natural light which creates long shadows from the<br />

west that helps to emphasise shadows, reflections of the objects and<br />

colours from objects. Shadows are boldly painted with the blue of the<br />

sky as it is reflected onto the surface, giving a sense of freshness and<br />

openness.<br />

Canaletto “View of<br />

Venice with St<br />

Mark’s” (Detailed)<br />

c.1735. Oil on<br />

canvas 46cm x<br />

63cm. Displayed in<br />

Huntington Art<br />

Collection, San<br />

Marino, California,<br />

USA<br />

Turner creates a much brighter image with fewer<br />

clouds. They appear as if they’ve been applied with a<br />

small pallet knife father than a brush. This creates a<br />

more three‐dimensional appearance, which both<br />

artists were good at portraying. One similar<br />

comparison is the shape of the clouds. They both<br />

create arches and shapes in the clouds to make them<br />

more realistic and not as blockish that can seem quite<br />

cartoon looking considering they both cut off the<br />

image, almost like a photograph. This will help with<br />

the importance of the sun coming through the clouds,<br />

making patches of shadows on the ground.

Although, Turner did enjoy the views of Italy, he also painted<br />

allegorical pieces which were more Romantic than the almost neoclassical<br />

looking images of Venice. Turner uses a completely different<br />

approach to “The Fighting Temeraire”.<br />

Turner did not necessarily use the importance of<br />

the sun as a tool to portray accurate landscapes<br />

like Vermeer and Canaletto, but with Canaletto’s<br />

influence, he used the sun as an allegoric<br />

message to the viewers of the 19 th century and<br />

onwards.<br />

Joseph Mallord William Turner<br />

The 'Fighting Temeraire' tugged to her Last Berth to be broken up<br />

1838‐39<br />

Oil on canvas, 91 x 122 cm<br />

National Gallery, London

During a time of evolving adaptations to dated resources of<br />

transportation, Turners painting of “The Fighting Temeraire” depicts an<br />

accurate portrait of new machinery taking over. The 98‐gun ship<br />

'Temeraire' played a distinguished role in Nelson's victory at the Battle<br />

of Trafalgar in 1805, which is where the famous name of ‘Fighting<br />

Temeraire‘ was derived from. The ship remained in service until 1838.<br />

Temeraire was ordered from Chatham Dockyard on 9 December 1790,<br />

designed by Surveyor of the Navy Sir John Henslow and commissioned<br />

on 21 March 1799 under Captain Peter Puget. The ship was part<br />

of Neptune class, along with HMS Neptune and HMS Dreadnought.<br />

Turner has portrayed the ship being towed from<br />

Sheerness to Rotherhithe to be broken up. The<br />

is suggested to represent the decline of Britain's<br />

naval power. The Victory and Temeraire<br />

defeated Napoleon's forces with combined<br />

tactics. Ultimately it was the Temeraire what<br />

lead Britain to victory. The monumental ship is<br />

contrasted by the the new steam‐powered ship<br />

that is tugging the larger ship behind.<br />

The old war ship towers over the new<br />

Steam power tug, which is portrayed with<br />

little personality. He records the sad moment in<br />

his painting.<br />

It was suggest the ship was pulled by two tugboats<br />

not one, but for the sake of Turners depiction, he<br />

only shows one. The ship is being tugged<br />

ultimately to her death where it will soon be<br />

broken up for scraps. The replacement of the<br />

steam‐powered ship is smaller and more prosaic<br />

in comparison and could move a lot quicker due to<br />

it being powered by steam.<br />

Turner portrays the Temeraire with lack of<br />

vibrancy, using warm but pale colours, but quite<br />

translucent like it has been unfinished compared<br />

to the rest of the painting. This gives a ‘ghost ship’<br />

appearance.<br />

A model of the HMS Temeraire (1798)

The first paddle tugs were steam powered which were first<br />

introduced to Britain. They were used to tow vessels up and down<br />

rivers, reducing the delays from having to wait for favourable tides<br />

and winds. The tug was the wooden hulled Monarch which was built<br />

by Edward Robson of South Shields in 1833. The tug was under 20m<br />

long and fitted with a 20HP single cylinder steam engine.<br />

The Monarch was acquired by John Watkins & William Ogilby in 1834<br />

and served the port of London until it was scrapped in 1876.<br />

It is portrayed a black and brown colour. This is not only the colour of<br />

the tug but it also depicts the colour of death in this case as it taking<br />

the Temeraire off. It has steam coming out showing the viewer it is a<br />

steam boat and it is pulling another ship.<br />

One of the attributes of a romantic painter is that they tend to use a<br />

triangular form, having the main feature at the point of the image.<br />

For this case, the Temeraire is the point of this triangular form. A<br />

white small craft farther down the river has been painted. However,<br />

the small boat and the third boat on the far‐right may seem like they<br />

have no purpose but it is helping to form the triangle and even out<br />

the image. Turner also uses a second triangular form, using a blue to<br />

frame around the three boats to broaden them the surface. This<br />

layout was also used by artists like Caspar David Fredrich.<br />

Caspar David Fredrich<br />

The Wanderer Above the Sea<br />

and Fog<br />

1818, oil on canvas<br />

98 ×74 cm<br />

Kunsthalle Hamburg

Turner uses warm tones on the Thames estuary which is at the river's<br />

eastern end. He portrays a lifeless surface with no ripples in the<br />

water, apart from around the stream boat where he uses a silver<br />

tone. The sun is behind the boats creating shadows to reflect in<br />

front. The background has been mostly devoid of objects to ensure<br />

the Termeraire is the focal point.<br />

“Light is therefore colour.” ‐ J. M. W. Turner<br />

This quote supports the importance of the sun to<br />

Turner. if there is so no light, there would be no<br />

colour to create a real life images.<br />

Turner uses pastel tones for the sky, with rapid brushstrokes.<br />

Although, he used oil paints, he applied paint with a palette knife, a<br />

tool usually reserved for mixing colours. Mixed with the paint he also<br />

used bees wax to lift the painting off the surface. This helped create<br />

a three‐dimensional look and allowed the canvas to catch light. As<br />

the sun sets above the estuary, its rays extend into the clouds above<br />

it, and across the surface of the water which create a warm yellow<br />

tone. The lighting in this piece was achieved through the emphasis of<br />

light and loose brushstrokes. The sun setting symbolises the end of<br />

an era in the history of the British Royal Navy and the<br />

commencement of the new, industrial era.<br />

It is suggested that the ship stands for Turner himself, with an<br />

accomplished past but now anticipating his mortality. Turner called<br />

The Fighting Temeraire his "darling", which may have been due to its<br />

beauty, or his identification with the subject. He intended to raise a<br />

sentimental and sad response from the viewer.

To conclude my research of the question how does Vermeer,<br />

Canaletto and Turner depict the importance of the sun in their<br />

artwork, we can easily see that it has developed over time and even<br />

used in various ways.<br />

One thing we know for sure is that the sun played a massive part to<br />

their artwork and their progress as Turner supposedly said before he<br />

died “The sun is God”. Without the sun, these artists wouldn’t have<br />

made as much as an impact on society, other artists and history for<br />

that matter.<br />

Vermeer depicted the importance as he used it generally in his<br />

paintings but he took advantage of the sun by using it in his artwork<br />

differently to how most people would imagine. In his later works,<br />

camera obscura was his saviour as he produced a lot of accurate<br />

panting's under this method. He found that the importance of the<br />

sun was what made his images and without it, there wouldn’t be as<br />

many treasures like the View of Delft or Little Street.<br />

Canaletto on the other hand, he also used the suns importance as a<br />

method of portraying his images like Vermeer. His were slightly more<br />

accurate as the lens soon came into the method. He also used it as a<br />

way of using strong chiaroscuro and reflecting the sun onto the<br />

lovely views of Venice which helped knowing what time of day it was.<br />

The sun was used as propaganda for his paintings<br />

to show everyone how wonderful it was in Venice<br />

so this was taken advantage of highly.<br />

Lastly, after Canaletto meeting Vermeer and<br />

Turner in the middle with his use of the sun,<br />

Turner used it completely differently to Vermeer.<br />

Turner was inspired by Canaletto so his use of sun<br />

was slightly similar. He didn’t use camera obscura<br />

but he did manage to get some lovely perspectives<br />

and sunshine of Venice.<br />

After Turners mother passing away, his images<br />

became a lot more meaningful where they were<br />

filled with emotion. He used the sun in many ways<br />

like displaying it in sunset painting to portray it’s<br />

natural beauty and colours or he used the<br />

importance as an allegorical message. Like in the<br />

Fighting Temeraire is setting which is suggesting it is<br />

setting on a new era.<br />

To conclude my question, they all show some link to<br />

each other and to the sun if it is visually there or<br />

somehow used to actually make the painting.

Mauritshuis. Published NA. “Johannes Vermeer, View of Delft, c. 1660 – 1661” (Online –last updated 2017) Available on:<br />

https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/explore/the‐collection/artworks/view‐of‐delft‐92/ ‐ last used on the 8 th March 2017.<br />

The National Gallery. Published NA. “Johannes Vermeer” (Online –last updated 2017) Available on:<br />

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/johannes‐vermeer ‐ Last used on 1 st March 2017.<br />

Essential Vermeer 2.0. Published NA. “Vermeer's Painting in the Context of the Dutch Golden Age of Painting” (Online –last updated<br />

2017) Available on: http://www.essentialvermeer.com/dutch‐painters/context/context_03.html#.WLbOTjuLTIU –last used on 1 st March<br />

2017.<br />

Martin Bailey. Published 1995. “Vermeer” (Book –last updated 1995) Available from pages: 60 – 62. Last used on 8 th March 2017.<br />

Tom Lubbock, The Independent. Published Thursday 9th October 2008 at 23:00. “View of Delft (1660) By Johannes Vermeer”<br />

(Newspaper –last updated Thursday 9th October 2008) Available on: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts‐entertainment/art/greatworks/view‐of‐delft‐1660‐by‐johannes‐vermeer‐956444.html<br />

‐ last used on 13th March 2017.<br />

The National Gallery. Published NA. “Canaletto” (Online –last updated 2017) Available on:<br />

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/canaletto ‐ last used on 14th March 2017.<br />

Canaletto. Published NA. “(Giovanni Antonio Canal) Canaletto Biography“(Online –last updated 2017) Available from:<br />

http://www.canalettogallery.org/biography.html ‐ last used on 14th March 2017.<br />

WebGallery. Published NA. “Canaletto Biography” (Online –last updated 2017) Available on:<br />

http://www.wga.hu/html_m/c/canalett/4/canal410.html ‐ last used on 13th March 2017.

British Art Studies by Roxane Sperber and Jen Stenger. Published NA. “Canaletto's Colour: the inspiration and implications of changing<br />

grounds, pigments” (Article –last updated 2017) Available on: http://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/issues/issue‐index/issue‐<br />

2/canaletto‐colour ‐ last used 14th March 2017.<br />

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Published 23rd July 2008. “Doges’ Palace Venice, Italy” (Article –last updated 23 rd July 2008)<br />

Available on: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Doges‐Palace ‐ last used 15th March 2017.<br />

BBC. Published NA. “History” (Online –last updated 2017) Available on:<br />

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/timeline/empireseapower_timeline_noflash.shtml ‐ last used on 15 th March 2017.<br />

ART written by Thames and Hudson. Published 2010. “View of Venice with St Mark’s c1735” (Book –last updated 2010) Available on:<br />

pages 258 – 259<br />

Reliquarian. Published 27th December 2012. “Saint Mark, Patron Saint of Venice” (Online –last updated 2017) Available on:<br />

https://reliquarian.com/2012/12/27/saint‐mark‐patron‐saint‐of‐venice/ ‐ last used on 16 th March 2017.<br />

The National Gallery. Published on the 18 th March 2016 narrated by Matthew Morgan. “J.M.W. Turner: Painting 'The Fighting<br />

Temeraire' | National Gallery” (Video –last updated 18 th March 2016) Available on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Ofna8HrWw<br />

–last used on 17 th March 2017.<br />

Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Complete Works. Published NA. “Joseph Mallord William Turner Biography”. (Online –last updated<br />

2017) Available on: http://www.william‐turner.org/biography.html ‐ last used on 18 th March 2017.<br />

Artble. Published NA. “Joseph Mallord William Turner”. (Online –last updated 2017) Available on:<br />

http://www.artble.com/artists/joseph_mallord_william_turner ‐ last used on 20 th March 2017.