Pottery In Australia Vol 3 No 1 May 1964

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

, A GAllERY OF MODERN ARTS<br />

<strong>Pottery</strong> from 28 leading AUSTRALIAN POTTERS,<br />

Sculpture, Paintings, Jewellery, Fabrics and Prints,<br />

Vitreous Enamel, Wood Articles, by <strong>Australia</strong>n Artists.<br />

Select <strong>Pottery</strong> from Denmark, Finland, Sweden,<br />

GermW!)I, Italy and Holland.<br />

*<br />

22 GA WLER PLACE, ADELAIDE<br />

TELEPHONE 8-7525

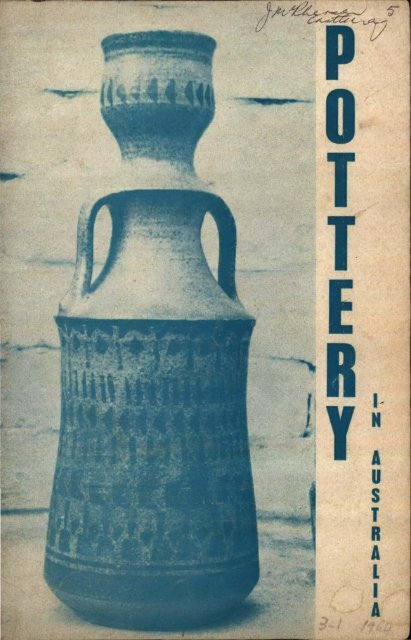

POTTERY<br />

I N AUSTRALIA<br />

Published by the Potters' Society of New South Wales<br />

Editorial Committee:<br />

Editor: Wanda Garnsey<br />

Sub-Editor: Brock Rowe<br />

Loy-out: Geoffrey Tyndall<br />

Business Monoger: Margaret Levy<br />

President: Mollie Douglas<br />

ERRATA<br />

Due to 'printer's error, continued lines were printed incorrectly.<br />

PAGE 42<br />

Article on this page is continued at foot of page 44 and not page 32.<br />

PAGE 13<br />

Article on this page is continued on page 37 and not pege 25.<br />

Please oddre.s all correspondence to The Editol of "<strong>Pottery</strong> in Austrolia",<br />

30 Tunomuno Avenue, Turromurra, N.S.W. T.lephone: 44-2043<br />

<strong>Vol</strong>. 3.-<strong>No</strong>. 1. MAY, <strong>1964</strong> FIVE SHILLINGS

CONTENTS<br />

<strong>Vol</strong>. 3.-<strong>No</strong>. 1. MAY, <strong>1964</strong><br />

Five Shillings<br />

Editorial<br />

Page<br />

Discovery of <strong>Pottery</strong> in <strong>No</strong>rth East Arnhem<br />

Land ... " . Ronald M. Berndt and Catherine Berndt 2<br />

<strong>Pottery</strong> in <strong>Australia</strong> ........ .. ................... Kenneth Hood 6<br />

Potters in Tasmania<br />

<strong>No</strong>tes from Perth on Mineral Glazes .<br />

Potters in South <strong>Australia</strong><br />

Thrumster Village <strong>Pottery</strong><br />

Vale John Chappell<br />

Takeichi Kawai<br />

A Potter Speaks<br />

1<br />

10<br />

Eileen Keys 12<br />

Dorothy Hope<br />

Les Blakebrough<br />

14<br />

14<br />

16<br />

Peter Rushforth 18<br />

Takeichi Kawai<br />

Some Folk <strong>Pottery</strong> of Central China Rewi Alley 34<br />

The Teaching of Hobby <strong>Pottery</strong>-<br />

Brisbane Report .............................. Milton Moon 35<br />

An Efficient Electric Kiln ................ Arthur Higgs 38<br />

Teaching <strong>Pottery</strong> in <strong>Australia</strong>n Schools-<br />

Ceramic Jewellery ........... ... Hildegarde Wulff 43<br />

Exhibitions and Lectures Joan McPherson 46<br />

Cover: Bernard Sahm (<strong>In</strong> the possession of the Art Galle'ry<br />

of N.SW'><br />

19

EDITORIAL<br />

It is fitting that this editian shauld feature <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

potters far, in the opinion of some of our critics, pottery in<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> is naw beginning to take its place with the ather<br />

arts.<br />

From the ranks of amateur potters, working in individual<br />

studias, influenced at first by their teachers and mentors but<br />

now expressing their own ideas with more definition, there<br />

is emerging much of vitality and strong personal expression<br />

to energise the local scene.<br />

<strong>No</strong>t yet is discernible a so called national style" reflecting<br />

our own un repeatable characteristics" - <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

pottery is derivative of other cultures in some degree. Perhaps<br />

we may never attain an entity of <strong>Australia</strong>n pottery expression,<br />

for two reasons. Firstly every well known potter works<br />

alone as an artist craftsman. There is no group activity here<br />

as there is in older countries where the association of many<br />

potters working tagether helps to create a style which after<br />

many years tends to grow into a tradition. These essential<br />

guilds of craftsmen arose out of a real need before the<br />

industrial concept replaced them, and this hardly applies<br />

ta us today.<br />

Secondly, an international outlook in human affairs<br />

becomes imperative for survival. Communications make it<br />

easy to see for ourselves how other people live and work,<br />

the barriers of race and creed die away in a common interest,<br />

and in the spirit of co-operation craftsmen unconsciously<br />

adopt a littlE! of the other's working methods.<br />

Nevertheless, as Takeichi Kawai says, "-all of us, in<br />

all generations and all countries share - have 'shared since<br />

the days of Adam and Eve - the essentially human qualities<br />

that make originality possible. Faithfulness to these qua lities<br />

which we have in common yet which declare our individuality<br />

-this is the ane thing needful."

DISCOVERY OF POTTERY IN NORTH -EASTERN ARNHEM<br />

LAND<br />

By Ronald M. Berndt and Catherine H. Berndt<br />

(Reprinted from the Journal of the Royal Anthropological<br />

<strong>In</strong>stitute, <strong>Vol</strong>ume 81 part 1/2, by permission of the Councii.)<br />

During anthropological resear

----------------------------------------------- ~------<br />

the Arafura and T imor Seas, and the narratives of their<br />

sojourn on the Austrolian mainland tell of the stane structur<br />

'~s they erected, the boats they came in, the women they<br />

brought, the cloth they wove and dyed, the fish they caught<br />

with spears, the gardens they cultivated, and the clothes they<br />

wore. <strong>In</strong> skin colour they differed from the Macassons, and<br />

were said to have been the golden brown colour of certain<br />

flying -foxes. Today, the Bajini epoch is looked upon as an<br />

event which occurred almost in the Ancestral Dreaming<br />

Period when the great Spirit Beings, who are the inspiration<br />

of clan tradition and religion, walked the earth. I n some<br />

stories the Bajini are said to have been contemporaneous<br />

with the greatest of all of the Ancestral Beings.<br />

It was, however, within what the aborigines themselves<br />

recognise as historical times that the ·Macassans and<br />

Malayans visited their shores in praus, caming on the northwestern<br />

monsoons in October and <strong>No</strong>vember, remaining for<br />

at least six months of the year, and returning when the<br />

south-east winds blew. At times ships and personnel remained<br />

all through the dry season to be on hand when the fleets<br />

arrived .at the beginning of the "Wet".<br />

Numerous comp sites, archaeological remains, old<br />

graves and tamarind trees testify to a prolonged association.<br />

It is in the great song cycles, however, and in the stories<br />

which survive, that a colourful picture of Malayan and<br />

Macassan life on these shores is unfolded.<br />

Large settlements were founded on the north-east and<br />

south-east coast of Arnhem Land, at such places as Arnhem<br />

Bay, Melville Bay, Port Bradshaw, Trial Bay, Caledon Bay,<br />

Groote Eylandt, etc. These visitors built stilted houses, roofed<br />

with cocanut palm leaves and fibre, and furnished them in<br />

an elementary fashion. Fowls, too, were kept, tiecl by one<br />

leg around which a ring ·was fastened, to the posts of the<br />

huts. Nearby they erected trepang boi lers. and racks for<br />

drying the sea-slug; and in the bays their ships were<br />

anchored, or being repaired. Each main settlement was a<br />

hive of industry, with Macassans and <strong>Australia</strong>n aborigines<br />

employed as labourers for specified payments. Bartering<br />

depots existed, to which local natives brought pearls, tortoiseshell<br />

and other natural products, and where they were given<br />

in exchange East <strong>In</strong>dia currency, introduced foods such as<br />

rice and sweetmeats, cloth, kn ives and tobacco. Trade was<br />

well establ ished, and its influences are still apporent today.<br />

Moreover, , these visitors not onl y brought products from<br />

their own country, but monufactured pottery, knives, cloth,<br />

sails ond other objects wh ile on the mainland. They olso<br />

exerted some influence on indigenous forms of material<br />

culture.<br />

This pottery was mode, so native informants relate<br />

3

(quoting from traditional stories which have been handed'<br />

down to them), with the help of aboriginal labourers. The<br />

"cloy" was obtained from local termite-mounds, the earth<br />

of which was broken down, crushed and mixed with water<br />

and kneaded to make it pliable. This "clay" was then turned<br />

an a primitive wooden wheel, but the p'rocess of making the<br />

wheel and the details of pot_making are unknown to the<br />

present generotion of natives. The pot which was the product<br />

was baked in an oven. These utensils were then used by<br />

natives and Macassans alike, principally for the purpose of<br />

boiling rice or for staring drinking water.<br />

THE SITES AND THE MATERIAL<br />

One of the most prolific sites for pottery shards today<br />

is at Port Bradshaw, about ten miles from the Yirrkalla Methodist<br />

Mission. This place, known by the native name Jelangbora,<br />

was an important area for the great duo moiety<br />

Ancestral Beings, the 'Djanggawal Sisters and Brother, who<br />

landed here in the Dreaming era; later it became a Bajini<br />

settlement, and then one of the largest Malayan and<br />

Macassan centres in north-eastern Arnhem Land. The latter<br />

visitors chose for their principal settlement 'Wobalinga<br />

Island, in the mouth of Port Bradshaw: here they built their<br />

huts, and manufactured pats. Much of this island today,<br />

including the original Macassan site, with its numerous<br />

scattered shards, is inundated at high tide. This appears<br />

to be the result of intensive erosion, brought about by'<br />

repeated chopping down of frontal foliage and trees. The<br />

majority of the specimens obtained here show water-markings<br />

and growth of barnacles, etc. <strong>Pottery</strong> shards were also<br />

obtained at other places in the vicinity of 'Wobalinga<br />

Island. Detailed topographical maps, drawn up by natives<br />

themselves, all reveal important Bajini and Macassan sites<br />

in north-eastern Arnhem Land, together with the presence<br />

of pottery shards, trepang pats, wrecks and sacred sites.<br />

The pottery collected demonstrates the variety of shapes<br />

in use; some have the impress of thumb or finger around<br />

their lips, and others again have elementary designs scrotched<br />

on the bowl 'below the lip. <strong>In</strong> addition to broken pots and<br />

bowls, some of which appear to have been very large, there<br />

are fragments of lids, handles, plates and stands. All seem<br />

ta be of approximately the same age and mostly of the<br />

same material, called "ant-pit" by the natives. Some specimens,<br />

.hawever, were probably brought to the north coast on<br />

the praus.<br />

<strong>No</strong> attempt is made here to reconstruct the utensils<br />

from the shards recovered, or to analyse the materials used<br />

in their manufacture.<br />

'The important point, particularly in the study of social<br />

origins and alien contact in Arnhem Land and the <strong>No</strong>rthern<br />

"

-------------------------------------------------------<br />

Territory generally, is that pottery was manufactured on<br />

the mainland of <strong>Australia</strong> with the aid of aborigines who<br />

have now forgotten the craft (which was of only superficial<br />

interest to them) ; that this pottery is by no means modern;<br />

that much of it was made from locally obtained 'termitemound<br />

earth; that the shards reveal a number of varieties<br />

of pots and other objects; that these shards show evidence<br />

of elementary designs on their surface, and thumb and finger<br />

prints below their lips; and that this pottery was used by<br />

aborigines who were resident on the alien settlements. These<br />

aspects are of major importance in understanding the history<br />

of acculturation in north-eastern Arnhem Land.<br />

To provide the preliminary data which led up to the<br />

finding of these shards, and which describe their use, we<br />

present a song from the Bajini-Macassan Song-Cycle. This<br />

song is in the diridja moiety dialect of the 'Gumoidj linguistic<br />

group, as spoken by the 'Rajang clan :<br />

Cooking rice on the fire; pouring it into a pot from a bag.<br />

Pouring rice from a bog : rice, rice, for food ...<br />

Rice from that bog: food from those rice-filled bags .. .<br />

<strong>In</strong>to pots of ant-hill earth . . . etc.<br />

NOTE : Another large deposit W9S found recently at Goulburn<br />

Island, Western Arnhem Land, and a selection of specimens<br />

is housed in the collections of the Department of Anthropology,<br />

University of Western <strong>Australia</strong>, and the Western<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n Museum .<br />

••••••••••••••••••••<br />

The January <strong>1964</strong> issue of Eastern Horizon features<br />

" Recent Discoveries in Chinese Ceramics" by Chen Wan-Ii<br />

wi th four pages of fine illustrations in colour. The origin<br />

of porcelain and a description of its firing conditions, as<br />

we ll as a type of early blue g lazed ware, a "proto celladon",<br />

is discussed by the author. Decorations in enamel on porce-'<br />

lain, common in ,the rAng dynasty, is traced back to the<br />

Eastern Ch in dynasty, following the discovery of shards in<br />

the remains of the Chongsha kiln.<br />

<strong>In</strong> the same issue, one of our contributors, Rewi Alley,<br />

describes his recent vis it to the site of the old Ting kilns<br />

with evidence in the debris of rare block Ting ware. Eastern<br />

Horizon can be obtained from Eastern Horizon Press, 18<br />

Causeway Road, lst floor, Hong Kong, for 3/- per issue, or<br />

30/- per annum, post free.<br />

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •<br />

Creative Clay Craft by Ernst Rottger at 34/9 is a useful<br />

I ittle book describing with illustrations various ways of<br />

awakening the creative imagination in students of pottery.<br />

Textures and design are demonstrated with the use of the<br />

simplest tools, and form is discovered as the characteristics<br />

of the material ore explored.<br />

5

POTTERY IN AUSTRALIA<br />

Kenneth Hood<br />

Reprinted by kind permission of the publ ishers of "HEMI <br />

SPHERE"<br />

During the past three or four years <strong>Australia</strong>n painting<br />

has received considerable publicity and· crit ical attention in<br />

0ther countries and, with the recently opened exhibition at<br />

the Tate Gallery in London, the overseas crit ics and public<br />

are becoming increasingly aware of the positian of our<br />

present-day art. But while we are consciaus af a new vitality<br />

in <strong>Australia</strong>n painting it is all too easy to forget that in<br />

the realm of the crafts much of a very high stQl ,dard is<br />

now being produced here.<br />

It has generally been held that in this country the cratts<br />

are a much later arrival on the cultural scene. Certainly it<br />

is true that there has been, since the last war, ·a tremendous<br />

upsurge of interest in the crafts generally and it is, perhaps,<br />

in the field of pottery that this new ond awakening interest<br />

is most obviously manifest.<br />

Yet <strong>Pottery</strong> has been produced in <strong>Australia</strong> from the<br />

earliest years of the nineteenth century. <strong>In</strong> the Sydney<br />

Gazette ond New South Wales Advertiser of September 18,<br />

1803, Samuel Skinner of Pitt's Row, Sydney, advertised his<br />

" Eorthenware Manufactory" and "respectfully acquainted his<br />

friends and the Public at large thot he had, by Assiduity and<br />

Perseverance, braught ta a state of Perfection in the Colony<br />

the above very useful and essential Branch of Manufacture;<br />

and that Ladies, Gentlemen, or Others who might be desirous<br />

of having Articles moulded to any particular Form, either<br />

for Utility or Ornament, would have their Commands<br />

punctually and reasonably camplied with". Then followed<br />

a list of the various wares for sale; some of these were :<br />

teapots 1 s. 6d. to 2s. 6d. each, cups and saucers 6d. to 10d.,<br />

cream jugs 4d. to 6d., mugs 6d. to 2s., children's tea sets<br />

4s. to 6s., etc. Mr. Skinner recommended them "as by no<br />

means inferior to the workmanship of the most eminent<br />

Potteries in the <strong>No</strong>rthern Country".<br />

This, then, is perhaps the first record of pottery making<br />

in one of the .Iarge intercolonial or international exhibitions<br />

IS rererred to only occasionally and then usually as an exhibit<br />

in <strong>Australia</strong>. During the rp.st of the nineteenth century pottery<br />

frequently held in Victorian times. Hawever, in the 1830's<br />

James King established a pottery at I rrawang in New South<br />

Wales .. The Sydney Herald of <strong>May</strong> 1, 1834, stated that a<br />

specimen of brown earthenware had been sent by King to<br />

their affice. Loter, in Octaber, 1836, the Sydney Gazette reported<br />

that· Mr. King, after considerable trouble and expense,<br />

had succeeded in bringing to perfection the manufacture of<br />

earthenware. The I rrawang <strong>Pottery</strong> was apparently so<br />

6

populor by 1845 thot demand exceeded production.<br />

At first the pottery sent to the international exhibitions<br />

was predominantly industrial. Stevenson and Sons and<br />

Young, George and liston sent flower pots, spirit jars, drain<br />

pipes and fire-bricks of clay from the Toorok quarries to<br />

the Melbourne Exhibition of 1854, but by the 1860's some<br />

domestic ware was beginning ta appear. Jars, pons and<br />

bottles for domestic use were exhibited by the Chesterfield<br />

<strong>Pottery</strong> Compony of Melbourne at the 1866 <strong>In</strong>ternational<br />

Exhibition in Melbourne, and Thomas Field of George Street,<br />

Sydney, and Alfred Carnwell af Brunswick, Melbourne, displayed<br />

"specimens of pottery" and "assorted stoneware" ot<br />

the same exhibition.<br />

Thus, whilst industrial ware such as fire-bricks and<br />

drain pipes continued ta be shown by Melbourne and Sydney<br />

potters at these nineteenth century exhibitions, we find that<br />

more and mare domestic ware began to appear, although na<br />

doubt this was in most cases little removed from the industrial<br />

product and not of a high artistic standard. The catalogue<br />

of the <strong>In</strong>ternatianal Exhibition held in London in 1872-3<br />

listed among the entries a "vase af pottery ware, a rock<br />

of calonial and other stoneware and pottery, five stone chino<br />

jars, two porcelain jugs, porcelain 'biscuit' or unglazed jug,<br />

earthenware speckled jug, faur porcelain vases tinted blue.<br />

earthenwate 'biscuit' vase and a bottle with porcelain gloze",<br />

and all of them mode of "Bulla Bulla cloy". At the Paris<br />

Universal Exhibition of 1867 only fire-bricks, fire-tiles and<br />

gorden-tiles had been shown whilst at the 1878 Paris<br />

Exhibition <strong>Australia</strong> was even less well represented : the<br />

Bendigo and Ballarat Freehold Company exhibited "samples<br />

of potter's clay" and G. D. Guthrie exhibited a "collection<br />

of pottery". But it seems that some rather more interesting<br />

wares were shown at the New Zealand and South Seas <strong>In</strong>ter_<br />

national Exhibition of 1889-90 when the Bendigo <strong>Pottery</strong><br />

Company limited showed "general pottery consisting of<br />

Porion, Majolica and Stoneware".<br />

The potter working in <strong>Australia</strong> in the latter part of<br />

the nineteenth century can hardly have been, even at this<br />

time, unaware af outside influences. <strong>Pottery</strong> and porcelain'<br />

from A:ustria. Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain (including<br />

jasper-ware from Wedgwood and Son), Ireland, <strong>In</strong>dia,<br />

Italy and New Zealand were shown with ceramics from<br />

Victoria and New South Wales at the Sydney <strong>In</strong>ternational<br />

Exhibition in 1879. That pottery-making in Austrolia hod,<br />

by this time, reached a comparatively high s~andard is clear<br />

from the report of the judges who said that "none of the<br />

intercolonial exhibits of glassware were worthy of particular<br />

mention, but the case was otherwise with the coarser kind<br />

of pot.tery, such as jars, pats, crucibles, drain-pipes and<br />

7

icks, in the production of which the Colonies are fairly<br />

well advanced, and of all of which they showed commendable<br />

-exhibits. Even objects of a higher order of artistic merit, such<br />

'as arnamental designs in terra-cotta were to be found among<br />

the exhibits in the Colonial Courts." .<br />

Despite this activity in pottery-making the nineteenthcentury<br />

potter in this country almost certainly had nothing<br />

in common with the artist-potter and his pots as we know<br />

them today. It was, in fact, only at this time that a cansiderable<br />

change was beginning to affect the work of the oaftsman<br />

in England and the modern artist_craftsman was being<br />

born. About the middle of the lost century J ohn Ruskin had<br />

initiated a return to the crofts of the mediaeval age - particularly<br />

a return to the spirit and attitude of the mediaeval<br />

craftsman and to the love of work for its own sake. For<br />

Morris and Ruskin it was essential that the craftsman should<br />

show in his work his joy in hand labour and a reflection of<br />

the material and spiritual climate of the less complicated<br />

Middle Ages. This, of course, was a reactian against the<br />

prevailing industrial and economic trends and it forced the<br />

craftsman to reconsider his relationship to, and place ' in.<br />

society. I t was the restrictive practices af the <strong>In</strong>dustria'l<br />

Revolution which caused the craftsman to lose direct'contact<br />

with his material and the control of every stage ' of the<br />

manufacture of his product. The Morfin Brothers, William<br />

de Morgan and Bernard Moore were among those who, in<br />

England, followed the lead of William Morris. The movemenl<br />

has continued to gain momentum and since 1920, when the<br />

Engl ish potter Bernard Leach returned from his first thp to<br />

Japan, the crafts in general and pottery in particular have<br />

received further and considerable stimulation. .<br />

We have sa-en that from early in the nfne'teenth century<br />

industrial or semi-industrial pottery and domestic earthenware<br />

were made. Shortly after 1900 a considerable quantity<br />

of white porcelain was imported to be hand-painted by<br />

young ladies - an elegant and genteel Edwardian ' accomplishment.<br />

It is not until 1911 that we find the first artist-potter,<br />

as the term is today understood, active in- <strong>Australia</strong>. 'He was<br />

·Merric Boyd, born in St. Kilda, Melbourne; in 1888.- Originally<br />

destined to be a farmer, Boyd arrived at p·ott.ery. by way 'of<br />

clay-modelling and he established his pottery workshop dt<br />

Murrumbeena in 1911.<br />

From the outset Merric Boyd's pottery was distinguished<br />

by art nouveau forms carrying a peculiarly <strong>Australia</strong>n feeling.<br />

It has been painted out (by John Yule) thot Boyd's "motifs<br />

derived from his obsessive· love of the primitive . element . in<br />

the country, the animals, the rough pioneer farmers".<br />

Primarily Merric Boyd's appraach to pottery was that<br />

af the expressionist and this expressionism "was transferred<br />

di rectly to 'clay vessels, jugs whase handles were twisted tree<br />

8

trunks, huge urns, heavily sculptured with animal and human<br />

figures". Fram 1917 until 1920 Boyd studied at Stoke-on<br />

Trent in England; on his return he continued to work at his<br />

pottery in Murrumbeena until his death in 1959. The<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n aborigines have never mode pottery and Merrie<br />

Boyd, unable to build on any long-established Austrolian<br />

tradition, took his inspiration directly from nature :' he<br />

attempted at the same time to establish a style recognisably<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> and to express in clay his love of his notive<br />

environment.<br />

Thus, the <strong>Australia</strong>n school of studio pottery was begun<br />

and, from this point, the popularity of pottery has grown<br />

steadily. Many of the pattery departments of our technical<br />

schools are now almost overflowing with students and more<br />

and more amateur potters are establishing kilns in suburban<br />

workshops.<br />

Mast of our studio patters are congregated in either<br />

Victoria or New South Wales. and in Sydney we find a<br />

Potters' Society which is actively supported by most potters<br />

in that State. Yet in, or close to, each of the other capital<br />

cit ies well-known potters are worki ng.<br />

To work in stoneware has become a lmost a fashion and,<br />

indeed, rather more than half of our potters work in th is<br />

medium now. Austral ian potters generally look to other<br />

countries and periods for their sources of influence and the<br />

Chinese ceramics of the T'ang and Sung periods have. in<br />

this regard, been valuable. The work of the contemporary<br />

English craftsmen, Bernard Leach, W. Staite Murray and<br />

Michael Cardew, has also been a fru itful influence. From<br />

both the Chinese and the contemporary Engl ish potters the<br />

interest now shown in stoneware is, probably, derived. However,<br />

our potters have recently become vitally conscious of<br />

the work of both the modern and the mediaeval Japanese<br />

potter and of the great craft revival there sponsored by the<br />

late Dr. Soetsu Yanagi.<br />

From small and humble beginnings, from merely industrial<br />

and semi.industrial ware to the .studio pottery movement<br />

as we know it today, the story of pottery in <strong>Australia</strong> is one<br />

of craftsmen striving to bridge the gap between art and<br />

industry. To counteract the monotony of most mass-production<br />

we need around us the work of the hand-craftsman,<br />

work which as Bernard Leach has said, "is at one and the<br />

same time recreation and labour and in which use and<br />

beauty are inseparable". Although the pots being made here<br />

by our artist-patters cannot, perhaps, yet rank with those<br />

of the great English potters and certainly not with those of<br />

the Chinese ar Japanese craftsmen, extremely fine pots in<br />

both stoneware and earthenware are being produced and<br />

the growing number of potters and societies indicates that,<br />

for the patter in this country, the situation at present is<br />

clearly one of tremendous vitality.<br />

9

POTTERS IN TASMANIA<br />

<strong>In</strong> recent years pottery is increasing in popularity in<br />

Tasmonia and as well as private pottery schools, technical<br />

colleges run extensive pottery classes. Mention is made here<br />

of some of the potters who have influenced ceromics in<br />

Tasmania.<br />

The first pottery in Tasmania was John Campbell's at<br />

Launceston which commenced in 1874, and still continues<br />

today as a fami ly concern, although in 1949 the pottery<br />

section closed down and now pipes and bricks are solely<br />

produced. However pottery from this source enjoyed great<br />

local and overseas popularity. <strong>In</strong> the 1880's, John Campbell<br />

built a small muffle' kiln and a hand wheel which was turned<br />

by a boy as the potter worked; and using local clays from<br />

Launceston and Beaconsfield he experimented with minerals<br />

and oxides. Exhibitions of this pottery, mainly earthenware<br />

and porcelain, were shown in Calcutta, Wembley and Victoria.<br />

<strong>Pottery</strong> was also exported to America and Iceland.<br />

Campbell's glazes were always clear, clean and glossy, a<br />

favourite being "honey on green".<br />

Among the contemporary potters, though a comparative<br />

newcomer to Tasmanio, Derek Smith is well known in N.S.W.,<br />

since his arrival from England in 1956. He trained in England<br />

as a special ist art-teacher for six years, two of which<br />

were entirely devoted to pottery, using industrial and hand<br />

methods. From 1947-1952 he was at the Loughborough<br />

College of Art, where he later taught part-time pottery, and<br />

from 1954-55 at the Leicester College of Art. <strong>In</strong> 1956 Derek<br />

Smith taught Art in N.S.W. High Schools, meanwhile potting<br />

and using on electric kiln. <strong>In</strong> 1958 he moved to Bowral,<br />

where he built an oil-fired kiln, producing stonewore and<br />

ceromic sculpture using local clays and rock glazes. At the<br />

beginning of 1963 he came to ' Hobart as lecturer at the<br />

School of Art, with pottery classes for art teachers in training<br />

ond for port-time students. He has built his own drip-feed<br />

oil kiln producing stoneware from local materials. <strong>In</strong> the<br />

past clay had been imported from Melbourne, but now<br />

local clay is being used for all practical work at the School<br />

of Art, and with the prospect of a pugmill, ballmill, and<br />

Leach type kickwheel, the overall picture for the future is<br />

promising.<br />

George Woodberry has his own pottery school and<br />

commercial pottery in Hobort. He studied art at East Sydney<br />

Technical College, at the Orban Studio, and with Bissietta.<br />

He later visited the South Seas, Europe and Japan, and<br />

admires the work of the Jopanese potters.<br />

The Montrose <strong>Pottery</strong> is a small Hobart Studio pottery<br />

run by Eileen Brooker, who is also an art and pottery teach!!r<br />

at the Fahan School. Blaz Kokor works with her and they<br />

10

make such individual utilitarian pots as coffee and tea sets,<br />

soup tureens with bowls, vases, dishes and ashtrays, oil in<br />

earthenware. Eileen Brooker was trained in England at King_<br />

wood <strong>Pottery</strong> in Surrey, which was started by Michael Cardew,<br />

and worked at various potteries in the Lakes District.<br />

The Killiney <strong>Pottery</strong> in Hobart is run principally as a<br />

school, where over 100 students are taught by Miss Mylie<br />

Peppin and Mrs. Hel.ena Chudackova, who holds an annual<br />

exhibition in Hobart. Mylie Peppin started the Killiney <strong>Pottery</strong><br />

with the assistance of Maud Poynter who trained in London.<br />

She was a pioneer who built her own pottery and wood fired<br />

kiln. Helena Chudackova was born in Czechoslovakia, started<br />

potting in Hobart, learning from Myl ie Peppin, taking aver<br />

the school in 1961 and remaining in partnership since that<br />

time.<br />

The Shavian <strong>Pottery</strong> at Howrah in Hobart is operated<br />

by Edward and Margaret Shaw and produces earthenware<br />

from Victorian and Tasmanian clays.<br />

Mrs. Audrey Beswick is a part-time instructor at the<br />

Launceston Technical College. She works in earthenware from<br />

local clays.<br />

Space does not permit mention of many other potters<br />

who have contributed something to the local scene, potters<br />

who by their industry and enthusiasm are adding great<br />

impetus to this craft movement in Tasmania.<br />

A man who shows great feeling for simple local material<br />

is Mr. Jeff Springer, of Relbia, Tasmania . His robust terra<br />

cotta garden pots show the influenc~<br />

both of the rough red<br />

clay and of the strength of the man who brings it to life.<br />

This clay is not far knick-nacks and ashtrays, a lthough it<br />

is used a lot by students. It shows its true character when<br />

thrown on a grand scale; Mr. Springer regularly throws up<br />

to 44 lb. of clay, making a pot 18 in. high. His largest effort<br />

was a tall vase of 88 Ibs.<br />

There are twa cool fired kilns at Relbia, a 12 ft. diameter<br />

down draught and a 9 ft. diam. up draught which are partly<br />

filled with the machine-made flower pots and agricultural<br />

pipes which are also made.<br />

Mr. Springer is generous with his knowledge and experience;<br />

to see his sure and businesslike throwing of big<br />

shapes is to be fired with a new enthusiasm for the potter's<br />

craft.<br />

These notes were sent in by Janet Jessop and Stephen<br />

Cox,<br />

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •<br />

11

NOTES FROM PERTH ON MINERAL GLAZES<br />

Eileen Keys<br />

All elements that potters use come from minerals<br />

whether they be cloy or rock. We ore living in on age of<br />

minerals, when great new discoveries have been made in<br />

Austrolia, as elsewhere, and it is certain that mare are yet<br />

to come.<br />

As potters in <strong>Australia</strong> are without a so-called "traditional"<br />

background I feel we should develop our own standards<br />

by making more use of those minerals that are in<br />

such abundance around us.<br />

The best pottery of all time come from the early Sung<br />

potters who used the crude materials they hod at hand.<br />

Many of the minerals we have today were not known to<br />

those potters, yet they mode very beautiful glozes, full of<br />

life and vitality, from the rocks they used with all their<br />

many impurities. All of the glozes needed simple forms to<br />

show their beauty. <strong>In</strong> later years, as the oxides were token<br />

from the ores ond refined, these glozes lost some of their<br />

former vitality.<br />

For those who wont to work in this way the first essential<br />

must be familiarity with the most common rocks and ores,<br />

including quartz, feldspar, iron, lead and zinc. You will<br />

soon come to know the common forms . A rock containing<br />

quortz obviously has a good basis of silica; lead and zinc<br />

perform their traditional fluxing action though tempered by<br />

the form in which it is found.<br />

You must become something of 0 "rock-hound", and<br />

that brings its own reword as one gets the "feel" of a rock<br />

by going to its source and seeing the lond from which it<br />

comes.<br />

If you live in a highly minerolised area you will prob·<br />

ably find that government surveys have been mode, the<br />

results of which are available. These will given you on ideo<br />

of the rocks you may work. Rutley's "Elements of Mineralogy"<br />

will also prove a great help.<br />

Londonderry, which is not so very for from Perth, in<br />

the general direction of Southern Cross, was once on area<br />

where nuggets of gold could be hod by picking them from<br />

the rocks. Today it is deserted, but by fossicking in the<br />

nearby fe ldspar quarry you can find many minerals suitable<br />

for the making of glozes; such, for instance, as the beautiful<br />

lilac-coloured rock, the colour of which is due to a small<br />

quantity of manganese and the decomposition of other<br />

minerals. There is spodumene, as well as many others.<br />

Igneous rocks contain a set of minerals differing from<br />

the sedimentary, many of which were the result of the<br />

weathering of existing rock types. Potters have always used<br />

igneous rocks such as feldspar and quartz, as well as many<br />

sedi mentary ont's<br />

12

The older minerals (metamorphic) are formed by the<br />

alteration of these sedimentary and igneous rocks through<br />

the action of heat, pressure and fluids, with the result that<br />

they are much harder. After having used many softer. rocks<br />

I find the harder ones more interesting. Minerals produced<br />

by the action of heat are different from those produced by<br />

stress as they contain more pebbles, quartz, lava, and so on.<br />

They do make a glaze, but there is not the interesting separation<br />

of the harder and rarer earths.<br />

When magma cools in nature, forming minerals, the<br />

conditions of cooling - whether these be quick or slowdetermine<br />

the crystals. The slower the rate of cooling the<br />

larger the crystals, and it is by its crystalline form that a<br />

mineral is most readily identified.<br />

Slow cooling in the kiln is essential if you wont<br />

separation of minerals and crystals. Most rock glozes need<br />

temperatures of 1160 deg. C. to 1300 deg. c., though I feel<br />

sure there is a wide field for research to be done at lower<br />

temperatures:<br />

Rock glozes do not shrink very much on cooling. The clay<br />

body will tend to shrink more and on opening the kiln one is<br />

liable to find pressure crocks. It is necessary,therefore, to<br />

add bentonite to most rock glazes and, as they must be thick,<br />

gum is also necessary. I find the knobs from a gum-tree the<br />

best gum of all as it does not deteriorate with time.<br />

You need to test the ashes of many trees for colour<br />

and fluxing action and when you are familiar with these<br />

you know the kind of ash your rock will need if you are not<br />

to spoil the colour of rock. Many potters today are using<br />

rocks again for colouring their glozes, but that was not my<br />

aim. I wonted to make the glaze from the ground rock itself,<br />

in line with my firm desire to keep as close to nature as<br />

possible in my work. I have tested some hundreds of rocks<br />

and I have many glozes with a wide range of colour and<br />

texture. It is only by repeated work with the rocks that you<br />

get the "feel" of what a rock needs. Many of our rocks<br />

contain iron and copper and it is very difficult to eliminate<br />

these. To the professional this may sound a long and<br />

roundabout method of procedure, but for the layman seeking<br />

something new it works.<br />

Let me worn you that rocks are unpredictable and one<br />

wonders if all the hard work is worth it, until you see a<br />

rock glaze coming from the kiln in beauty that cannot be<br />

obtained in any other way. Unfortunately rocks need grinding.<br />

First, they must be broken up with a hammer and then,<br />

using a miner's "dolly pot", they can be ground still finer<br />

and put through on 80 sieve. (I find it is not wise to grind<br />

them too fine.l You could work first with just one rock,<br />

experimenting with the addition of ash and the firing conditions,<br />

and observing all the different results.<br />

CONTINUED ON PAGE 25<br />

13

POTTERS IN SOUTH AUSTRA LIA<br />

Great interest is taken in pottery in Adelaide. There are<br />

two amateur clubs - the Adelaide Potters' Club, and the<br />

Studio Potters' Club, each having a membership of several<br />

hundred. Bath clubs have exhibitions annually, and although<br />

some of the work is not of high standard, it is improving in<br />

taste and technique each year.<br />

The School of ATts has a Ceramic Department run by<br />

Mr. Kypridakis who has recently come from America and<br />

has been experimenting with Raku firings. Classes this year<br />

are working with stoneware. Some af the Technical Schools<br />

also have pottery classes for teenagers and adults.<br />

. There are several outstanding potters in Adelaide; the<br />

be~t known perhaps is Alex Leckie. Another potter who<br />

makes beautiful stoneware is Helen Mcintosh, and a third<br />

who has recently exhibited in the White Studio is Frank<br />

Weston.<br />

Each year there is a Ceramic Section in the Advertiser<br />

Open-Air Art Exhibition, and during the Festival of Arts,<br />

pottery is very much to the fore.<br />

This year the Royal S.A. Society of Arts arranged an<br />

exhibition of ceramics and sculpture in conjunction with<br />

the Austra lian and New Zealand <strong>Pottery</strong> Exhibition organised<br />

on behalf of all <strong>Australia</strong>n National Galleries by Kenneth<br />

Hood of the National Gallery of Victoria.<br />

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •<br />

THRUMSTER VILLAGE POTTERY<br />

Dorothy Hope<br />

A potter need not be sentimental about the way in<br />

which the early potters utilised their local materials to feel<br />

that this approach to pottery is fundamentally right.<br />

As this area

SiO. . ................... ...... .... ..<br />

Al,Os ............................ ..<br />

Cr. . ......... ........... .. ..... ..... .<br />

CaO ... .. .... ...................... .<br />

MgO ............ ................. .<br />

COO<br />

Na ............................... .<br />

K ... .. ..... ............ ......... .... .<br />

P ................ ...... .<br />

S<br />

Ign ition loss ......... ...... ..<br />

24.40<br />

24.00<br />

0.27<br />

Trace<br />

Trace<br />

Trace<br />

0.50<br />

0.50<br />

0.05<br />

Trace<br />

5.26<br />

80.57<br />

Balance due to water content, etc.<br />

After working with these materia ls for some time I<br />

have found that the clay and colours are at their best when<br />

fired to 1100 deg. C. and held at that temperature for 30<br />

minutes. The resulting ware, a range of teapots, coffee pots,<br />

mugs, jugs, covered pots and large bowls has a fine-textured<br />

finish, of low porosity and well suited to modern demands.<br />

To me, this is the pottery that is most satisfying to produce.<br />

.. With the few materials used, the requirements of the<br />

workshop routine and the layout can be kept simple and<br />

uncluttered. All the pots are thrown, and decorated on the<br />

wheel, proving the adequacy of this .method of production<br />

for a small workshop, as against production with moulds,<br />

where one. is faced by an encumbrance of moulds and the<br />

embarrassment of shapes that don't work out.<br />

The showroom and workshop adjoin to allow visitors<br />

a view of the work in progress without undue interruption or<br />

intrusion. This has resulted in a lot of interest from visitors<br />

to the area, a fact wh ich is not mentioned for mercenary<br />

reasons, but to point out· that there is a place in today's<br />

society for the craftsman potter who loves the work enough<br />

to devote time and energy to it, and the extra effort needed<br />

to share it with the people who are interested.<br />

Adjoining the warkshop and showroom is a building of<br />

camplementary design. Both buildings were designed and<br />

built by Jack Hope from timbers cut on the property and<br />

are situated in a bushland setting.<br />

The second building is used as a crafts centre for<br />

various art exhibitions, demonstrations of wood carving,<br />

weaving, etc. It is also used as a meeting place for an<br />

occasional weekend school of pottery students who come<br />

from the <strong>No</strong>rth Coast and Western districts.<br />

The pottery has taken its name from the site of<br />

Thrumster villoge which has associations with early convict<br />

days and is situated five miles from Port Macquarie.<br />

15

VALE JOHN CHAPPELL<br />

Les Blakebrough<br />

The Editor has asked me to write a short biography<br />

about the late John Chappell. It is not an easy task, especially<br />

for someone who is reluctant to write -anything; however,<br />

Chappell was a close friend of mine and so perhaps a few<br />

recollections of our friendship will be of interest. It is not<br />

intended that this is even a biographical sketch.<br />

We met when John and his wife were on their way<br />

to New Zealand for a six-month lecture tour, in December,<br />

1960. They spent ten days with us at Mittagong while<br />

waiting for a ship to take them across the Tasman .<br />

. He had a crazy way-out sense of humour and the reaction<br />

was immediate - we were friends within minutes of<br />

meeting. A common interest made it easy for the friendship<br />

to develop. During those few days in 1960 talk in the pottery<br />

or over the dinner table always got round to life and potting<br />

in Japan, where he had been living for the previous two<br />

years. At this time the seed was sown for us to visit Japan.<br />

The idea materialised in December, 1962, when we left<br />

Mittagang to spend a year there.<br />

We arrived in the middle of the worst winter Japan<br />

had seen in the last 50 years, with heavy snow everywhere.<br />

John met us in Nagoya and took us straight to his home in<br />

the country near Kyoto. A strange language, food and<br />

general atmosphere were overwhelming to begin with and<br />

John's help and kindness made the first few weeks much<br />

more bearable. We lived with him for about four months<br />

and during this period I worked with him in his workshop.<br />

We got to know him very well in these months, sharing his<br />

frustrations and disappointments as well as all the laughs,<br />

and there were lots of these.<br />

He was an amozing person to work with; there was<br />

always some deadline to meet - a show in Tokyo or Osaka,<br />

or a competition elsewhere - but with a final flourish all<br />

was ready, usually if it were pots, with the kiln being<br />

unpacked very hot and then half an hour to parcel up and<br />

catch a train . .<br />

His ability to organise things in a hurry was incredible,<br />

and when space was getting scarce in the pottery he decided<br />

to build a store house. The idea was conceived on Sunday,<br />

an Monday the t imber was ordered and delivered and by<br />

Thursday, with the two of us working like maniacs, it was<br />

completed and filled with fired pots' A bath house was made<br />

under much the same circumstances, large enough for two<br />

people to sit in at the same time and was christened after<br />

a long and dirty firing with lovely hot water up to our beards<br />

and two bottles of beer within easy reach. John's organising<br />

ability was seen at its best one Sunday in the summer when<br />

16<br />

/-ll

the American poets, Garry Snyder and Allen Ginsberg, with<br />

a group of other people came out to Do Mura for a picnic<br />

and swim. John persuaded them to walk up into the hills<br />

where he said there was a lovely rock pool. We arrived to<br />

find a small pool with a foot of water in it! "<strong>No</strong> matter, we<br />

can dam up one end and the water level will go up three<br />

feet," claimed John. Well, he actually persuaded everyone,<br />

including Ginsberg, to cart rocks to make a dam and lat"er<br />

in the day the idea actually worked.<br />

Usually it was never necessary to make suggestions to<br />

John -<br />

life was hectic enough without making it more so,<br />

but at times one was apt to forget and a suggestion once<br />

made, even if there were only a glimmer of feasibility in it,<br />

would be taken up. There was a problem of how to fit in<br />

a certain number of firings before one of his exhibitions.<br />

Well, crazy as it may sound, it wos decided to fire the<br />

stoneware kiln and as soon as it was finished to switch the<br />

drip feed arrangement over to the salt glaze chamber and<br />

fire it; the two firings took 32 hours. Life with Choppell<br />

was pretty much a string of events like these, at a pace, as<br />

full as it is possible to be with a well-developed sense of<br />

humour flowing most of the time.<br />

Chappell had many talents; apart from being a f ine<br />

potter, he had an ·alert and enquiring mind and would have<br />

made a good political commentator. People who knew him<br />

would probably agree. He was a convincing talker. He was<br />

also a very good cook and at one time worked as a chef in<br />

london and later in France.<br />

However, it was with clay that his ability was evident.<br />

His standards were high and he expected the same of other<br />

potters. He was able to practise what he preached. He<br />

followed on uncompromising way with his pots which had a<br />

peculiar way of being somewhere half way between what<br />

we have come to term "Eastern" and "Western". He<br />

achieved this assimilation better thon anyone else I can<br />

think of in an unselfconscious way. His pots were not "Japanese"<br />

and not "English" but unique, and an extension af<br />

himself.<br />

That he was killed is a tragedy because he was in the<br />

process of mature development. There was a well of physical<br />

and creative energy that few people have. Those who saw<br />

his exhibition at the Macquarie Gallery in Sydney in February<br />

this year can decide for themselves, but to make the scene<br />

as he did in Japon, where competition is unbelievably competitive<br />

and where critics are severe, intelligent ond well<br />

informed, was an achievement and the reward af being a<br />

fearless, creative potter. His pots will speak for themselves.<br />

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •<br />

17

T AKEICHI KAWAI<br />

Peter Rushforth<br />

Takeichi Kawai works and lives in Kyoto, the cultural<br />

centre of Japan. His training as a potter has followed the<br />

custom of long years of apprenticeship, in his case, under<br />

his uncle, the famous Kanjiro Kawai. To many who bel ieve<br />

in this system of training it would be considered pretentious<br />

to exhibit at an early age-Mr. Kawai had his first exhibition<br />

when he was fifty, at· a time when his work and outlook<br />

had matured. <strong>In</strong> January this year, he arrived in <strong>Australia</strong><br />

and exhibited h is work in Sydney.<br />

This exhibitian was significant for many reasons; it<br />

was the first one-man exhibition to be held in <strong>Australia</strong> by<br />

a leading overseas artist-potter and ·it focused attention on<br />

the contribution the individual potter can make to the<br />

environmental pattern. To students it exemplified the creative<br />

possibilities of stoneware techniques and how a traditional<br />

idiom can be infused with freshness and vitality; it also<br />

showed a surety which undoubtedly stems from the Zen<br />

advice: "Develop an infallible technique, and then place<br />

yourself at the mercy of inspiration. II<br />

The work also reflected some of the spirit and atmosphere<br />

of Kyoto where for over a period of a thousand years<br />

Japanese artists and craftsmen have developed their work<br />

under the influence of Buddhist thought, caurt activity and<br />

Shinto traditions. However, the main influence, which Mr.<br />

Kawai readily acknowledges, has emanated from the Mingei<br />

or Folk Craft School and the philosophy of Dr. Soetsu Yanagi<br />

wh ich places humility before the cult of the individual and<br />

seeks to find meaning in life through a search for beauty<br />

in everydoy living. It is this attitude wh ich hos prompted<br />

Gropius to write, lilt has been my impression that the<br />

Western mind in its restless desire to seek new horizons in<br />

the physical world, would do well to I·earn a lesson of<br />

spiritual intensification from the Oriental mind, that is, how<br />

to seek new horizons in the inner world".<br />

<strong>In</strong> coming to <strong>Australia</strong> personally to exhibit his ·work,<br />

Takeichi Kawai has contributed to the strengthening of an<br />

intemational bond which is developing amongst artists and<br />

craftsmen. During his stay he has generously given his time<br />

to lecture, demonstrate and share h is knowledge and t raining.<br />

At the National Art School under the disconcerting<br />

glare of television cameras Kawai unconcernedly demanstrated<br />

on a Japanese kick wheel before an appreciative<br />

audience of students. On his return from New Zealand in<br />

April he lectured for the Oriental Society at Sydney University<br />

where he expressed his attitude towards the potter<br />

in society.<br />

As Takeichi Kawa i returns to Japan he ~ takes with<br />

h im the good wishes of many <strong>Australia</strong>ns and the lasting<br />

friendship of those of us who were connected with his visit.<br />

18

A POTTER SPEAKS<br />

TAKEICHI KAW"I<br />

From a Talk given at the University of Sydney<br />

It is on unexpected honour and pleasure for a Japanese<br />

potter like myself to speak at this distinguished University.<br />

I am most grateful to those who have given me this<br />

opportunity.<br />

The precursor of the pottery, and for that matter of the<br />

utensils, that all of us use today was, I suppose, the human<br />

hand, which once served as plate or bowl or knife and fork.<br />

Hands were all-purpose tools, one might soy quite literally.<br />

And thlln in the course of evolution come discovery of fire,.<br />

with all its consequences for every culture. Primitive peoples<br />

found out how to make a substitute for hands by maulding<br />

and then heating clay - a gradual development that must<br />

have stretched over on immense period af time. The next<br />

great step was token in Egypt or Persia, where a fortunate<br />

cambinatian af natural resaurces and a dry hat climate led<br />

to the discovery that lumps of glass could be manufactured<br />

by subjecting a mixture of sand and soda to the sun's heat,<br />

and that a solution of powdered glass could be applied to<br />

clay vessels before baking ta produce a glaze. <strong>In</strong>numerable<br />

pioneers, generation after generation, must have contributed<br />

to make this possible. Such memorablet ' ioneer work, decisive<br />

for the growth of the art, waul in modern times<br />

naturally be awarded a <strong>No</strong>bel or some similar prize: but<br />

the river of historical development flows on, obliterating<br />

ephemeral landmarks, so that we can name none of the<br />

men to whom we owe these great achievements.<br />

As far as the Orient is concerned, Chino is regarded as<br />

the birthplace of the art af ceramics. The long tradition of ,<br />

Chinese pottery developed continuously to the stage of<br />

glozing by means of repeated exposure of a surface to very<br />

high temperatures, followed by the application of a glaze<br />

made from clay and ashes. After the discovery of glaze in<br />

the Han period came a succession of golden ages, the glories<br />

of T'ang, Sung and Ming pattery - the product of the<br />

limitless resources of that huge land and of the loving<br />

appreciation by generations of discriminating collectors.<br />

Today, as you are well aware, Chinese pottery is represented<br />

in museums and art galleries throughout the world.<br />

Limited productian b)' hand increased dramatically as<br />

what one might call the' potter's machine" come into use.<br />

This innovation - a platform placed upon a vertical pivot<br />

with a horizantal supporting arm, dates, as glaze does, fram<br />

the Han period. Both hand-driven and foot-driven types<br />

were in common use. We Oriental potters of today owe<br />

everything to the skill and ingenuity of our predecessors of<br />

2,000 years ago. <strong>In</strong> this connectian, I sholl never forget the<br />

fine autumn day 23 years ago - it was October 15th, to be<br />

precise - when I was fartunate enough to look upan the<br />

19

Great Wall of China, one of the Seven Wonders of the world.<br />

It dates from the third century B.C., the period of earthenware<br />

pure and simple, before the invention of the glazing<br />

process. For all the urgency of the fear of foreign aggression<br />

that drove the Emperor Shih Huang Ti to build this fortification,<br />

one can only marvel at the sheer grandeur of the Wall,<br />

stretching as it does for seventeen hundred miles or more<br />

along the mountain ridges, and at' the dynamic energy of<br />

those who erected it. It is covered throughout with tiles 1 ft.<br />

2 in. square by ! in. thick, hundreds of millions of tiles in<br />

all. The name of the Emperor, Shih Huang Ti, has survived:<br />

the mill ions who worked on his project are forgotten - so<br />

few traces does history leave behind of the men who make<br />

it. I felt afresh the fitness of the lines the Japanese poet<br />

wrote as he looked upon the grassy moor where one of the<br />

most vital battles in all Japanese history had ' been fought<br />

little more than two generations eorlier-<br />

Summer grasses<br />

All that remains<br />

Of the warriors' dream.<br />

<strong>In</strong> the fulness of time the techniques of ceramics were<br />

introduced from China into Korea, whose potters mastered<br />

them so completely as to be able to go further, and to make<br />

pots which ore distinctively Korean, which could not be '<br />

anything but Korean. (There is no single style of pottery.<br />

One penetrating classification recognises three main styles,<br />

corresponding to "mind", "feeling" and "will".)<br />

And so to Jopan - where many traditional methods are<br />

better preserved, I think one may say, than in China itself.<br />

But a country cannot hope to match work that was not its<br />

own original product, however nearly that may be possible<br />

by using such aids as exhaustive chemical analysis. What<br />

is really valuable is what a country produces of itself, on<br />

its awn, reflecting its own unrepeatable characteristics. <strong>No</strong><br />

one questions the massive contributions that Kyoto, our<br />

capital city for a thousand years, has made to Japanese<br />

culture. Potters responded to the needs of such arts as<br />

flower-arrangement and tea-ceremony that came to be practised<br />

there - hence the fine tea-bawls and great variety in<br />

size and shape of flower-vases. (Both tea and flowers are<br />

flourishing, I understand, throughout <strong>Australia</strong>.). From about<br />

four hundred years ago individual potters of genius - whose<br />

names are known - began to emerge. Two generations ago<br />

we in Japan were reminded by the Master Yanagi Muneyoshi<br />

that while the creations of individual genius have their own<br />

special, immediately recognisable excellence, there is more<br />

beauty in the work of nameless craftsmen. Hence the foundation<br />

50 years ago of the Japan Folk Art Centre, for the<br />

display of pots from Japan, Chino, Korea and other countries.<br />

It is different from a museum or on art gallery: one experi-<br />

20

ti<br />

~<br />

:0<br />

•<br />

o<br />

..<br />

i<br />

~ •<br />

.<<br />

0.<br />

2<br />

.. ~<br />

..<br />

..<br />

• o<br />

.li<br />

... •<br />

J!<br />

..

·•<br />

E<br />

~ •<br />

i<br />

i<br />

;<br />

f

Takelchi Kawai

..<br />

%<br />

•<br />

.:!<br />

%<br />

~<br />

•<br />

...<br />

""<br />

j<br />

;<br />

..<br />

?..<br />

• <<br />

a:

FRONT VIEW <<br />

lid- - +--<br />

pilot<br />

light<br />

"T<br />

l.r~<br />

--.no<br />

e e~. 0 "<br />

~~~ i :----c<br />

'iI--,,.-----+tt"- SOf~t-c -.--" J" :<br />

I<br />

3 - h ~ a t..

-lid c:pcn<br />

ELECTRIC KILN<br />

le"x I SiX IS 1\<br />

BRICKWORK<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

------ - --<br />

A<br />

... " -I<br />

I--<br />

1<br />

I--<br />

fl" row<br />

l~rdrow<br />

-".--'<br />

-<br />

I--<br />

~IT<br />

DI~RAM<br />

1<br />

1'"-/8 _" --""'1<br />

] I<br />

l-<br />

I<br />

I<br />

f-<br />

[2.". row<br />

14!"rCNI<br />

(r~bat( on<br />

top rOIl<br />

only)

"•<br />

o<br />

;.<br />

...<br />

:z:<br />

•<br />

11

A dilplay of students' pots at the Workshop Arh Centre, Willoughby.<br />

Photogroph by Doug Ker,igon.

Wall of wasters# lehang.<br />

Bowls, Hupeh Proylnce.

John Chappell at Do Muro.<br />

John Choppell: Macquarie Galleries.<br />

Photogroph, Jomes Robinson.

ences a peculiar warmth on looking at the pots exhibited at<br />

the Centre, a sense of closeness to the invisible craftsmanan<br />

"energising" feeling that though these are masterpieces,<br />

we might after all be able to achieve something not ~o<br />

very inferior ourselves.<br />

The motive of response to practical need - of which<br />

I spoke a moment ago - is also, of course, the starting point<br />

on the road to mass-production, in whose name so much<br />

worthless work is foisted upon us today. If this depresses you,<br />

I would ask you to remember that all of us, in all generations<br />

and all countries, share - have shared, since the days of<br />

Adam and Eve - the essential human qualities that make<br />

originality possible. Faithfulness to these qualities which we<br />

have in common yet which declare our individuality - this<br />

is the one thing needful. During my visit to <strong>Australia</strong> I<br />

have been able to meet many <strong>Australia</strong>n potters, and have<br />

been struck by their enthusiasm for this craft of ours. Some<br />

complain of the drawback of working in a country with such<br />

a brief history, where there has hardly been time for tradition<br />

to form . But you have the potentiality, as does every other<br />

country; and I have no doubt that before long pots will be<br />

made in <strong>Australia</strong> that wil l be truly and unmistokeobly<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n. Let us avoid at all costs the "internationalisation"<br />

of the art, the neutral international style. Pots are<br />

worthless, I would say, if they do not reflect the culture of<br />

the country of their origin. How eagerly and confidently we<br />

can look forward to the future creative work, in this and<br />

similar fields, of the young generation of <strong>Australia</strong>ns whom<br />

you <strong>In</strong> this audience represent!<br />

••••••••••••••••••••<br />

33

SOME FOLK POTTERY OF CENTRAL CHINA . ..<br />

REWI ALLEY<br />

There are ten thousand unfrequented paths into the field<br />

of the Chinese potter. At almost every turn one comes upon<br />

a new one. There are the new research institutes into<br />

ceramincs in the cities, the big state-owned modern porcelains<br />

kilns, and then again there are in the villages of the hinterland<br />

the myriad small kilns now operated by commune work<br />

teams which turn out do ily-use pottery and sometimes porcelain<br />

for the village markets'. Village life would hardly be<br />

possible without the potter. The big jars that salt down<br />

winter vegetables or are used to store household groin, the<br />

pots for sauce and vinegar, the humble' night pot that goes<br />

under the bed, as well as the decorative pieces that bring<br />

a laugh to the home---

THE TEACHING OF HOBBY POTTERY-Brisbane Report<br />

Milton Moon<br />

Students taking pottery at Brisbane's Central Technical<br />

Callege may enrol as Diploma, Certificate or Hobby students.<br />

As both the Diploma and Certificate courses follow a prescribed<br />

syllabus these present no great problem for the<br />

teacher, but it is with the Hobby student that teaching<br />

difficulties are experienced, students being as they ore fram<br />

many walks of life and having many and varied reasons far<br />

undertaking the course. I should imagine that this is not<br />

confined to Brisbane alone as most enralments in pottery<br />

schools are by people wishing to take the subject on a hobby<br />

level. Students in this hobby category at our school fall inta<br />

one or more of the following groups:<br />

. Student teochers, or teachers, who are taking an extra<br />

curricula course in pottery ta supplement the little they are<br />

taught in teacher training establishments, so that they may<br />

teach the subject in schools.<br />

Those engaged in therapy work who wish to introduce<br />

this type of activity along with other therapeutic work.<br />

Hobbyists who take the subject as a craft/art autlet.<br />

Hobbyists who wish to eventually become self-employed<br />

as Studio Potters.<br />

Because of the different aims af the students and<br />

because af their 'diversity af experience and ability, and<br />

differences in education background, it is desirable that<br />

students fallow a standard course which can be tackled at<br />

the student's own speed. And, because the object of a<br />

technical institution is to educate, the programme is designed<br />

to teach students more abaut pottery as a subject rather<br />

than let them embark on a personal "catch as catch can"<br />

programme which may be very desirable from same points<br />

of view, but which is not likely to teach much about the<br />

subject of pottery itself. Consequently, the work taught to<br />

all students taking the hobby course is primarily of a<br />

disciplined nature - strict pattery procedure and a logical<br />

course or plan of study being the first objective, in the<br />

belief that a person can achieve valid self-expression either<br />

within or outside convention much better, if there is a<br />

greater understanding of the material, and a knowledg'e of<br />

the vocabulary of expression contained within form, glaze<br />

and decoration.<br />

There has been- a tremendous increase in the number<br />

of people taking pottery as a subject. This is quickly leading<br />

to a situation similar to that in some overseas art schools<br />

where pottery students form the ma/'or enrolment. At Brisbane's<br />

Central Technical College enro ment is limited because<br />

of space - but this .situation will be rectified in time.<br />

Despite the deficiencies caused by inadequate space, the<br />

35

equipment is sufficient to meet present demands. This<br />

includes Blunger, Clay mixer; filter-press; pugmill; seven<br />

electric wheels, one of which is a heavy industrial machine,<br />

with jigger/jolly attachments; two Uscinski kilns (a remarkable<br />

kiln with automatic shut-off devices and sealed elements<br />

suitable for use to 1400 deg. C. under pxidation or reduction<br />

over an 8 hour cycle); other kilns include a 10 cubic foot<br />

e lectric kiln for bisque and earthenware glost, and two gas<br />

kilns of approx. 10 cubic feet each, one natural draft, the<br />

other forced draft, both suitable for use to 1350 deg C. over<br />

a nine hour cycle. Both gas kilns were locally designed and<br />

built.<br />

Clay bodies, engobes and underglazes are made at the<br />

college. Three earthenware glazes are used - all are purchased<br />

and altered for individual effect. Four stoneware<br />

glozes are used - we make these at the college using local<br />

materials. These glazes are:<br />

one satin ash talc glaze,<br />

one heavy cloy matt,<br />

one high feldspar/limestone glaze,<br />

And a celadon which is mode to a different formula<br />

each time it is made. All items are labelled with the formula<br />

and description so that each student, taking proper notes<br />

can have a personal and complete record of their own work.<br />

Three college-made clay bodies are available for sale, but<br />

students are given a separate body for practice purposes;<br />

work done in practice clay may not be kept. Students are<br />

completely responsible for their own work, including glozing.<br />

Advanced students are allowed to pack and bisque their<br />

own ware then gloze and glost-fire in a Uscinski kiln. The<br />

early parts of firing, steoming etc., is done during class, and<br />

the kiln having on automatic shut-off device, virtually fires<br />

itself, but in this way the student can take the work to<br />

completion.<br />

Formal lectures on clay technology and glaze formulation<br />

are not given to hobby students, but suggested books<br />

and chapters are outlined to ·cover these subjects. Advanced<br />

students wishing to formulate individual glazes may do so<br />

under supervision. As for decoration, there is a list of twentytwo<br />

pots, incorporating different decoration techniques<br />

which must be followed by every student. This sequence has<br />

been planned so that decoration is shown as a logical<br />

sequence, covering earthenware to stoneware and differences<br />

obtained by firing in different atmospheres. (I hope that<br />

next year the compulsory list will number some fifty pots')<br />

<strong>In</strong> this way, all an instructor need know, to give pertinent<br />

criticism and advice, is what number pat and effect the<br />

student is doing.<br />

All students are taught wheel-throwing at the outset.<br />

36

-----------------<br />

All forms of hand-building a re encouraged, but there is no<br />

compulsion to do this before learning wheel-work. All schoolteachers<br />

though are urged to hand-build and to concentrate<br />

on effects goined from bon-firing. (Frankly, I feel it is<br />

much better to opproach primory and secondory school<br />

pottery on the primitive level, rather than by the employment<br />

of wheels and kilns. Great beouty of work and extreme<br />

satisfaction can be gained by working at this level. Just<br />

consider the work of the American aborigine.)<br />

<strong>No</strong> student at the Central Techn ical College may keep<br />

work done in the first term, with the exception of a personal<br />

tea-bowl which the student may pinch-build. If this seems.<br />

a little harsh, it has proved to be of a great benefit - the<br />

standard has risen immeasurably since this began -<br />

student seems to take pride in the fact that they are<br />

approaching the subject seriously and I have not struck<br />

One case where the student has shown resentment of this<br />

condition. It is pointed out that na type of pottery is better<br />

or worse, no method of building is superior, rather it is the<br />

end-product which is judged. As much as possible the onus<br />

of learning is thrown di rectly on to the student. The College<br />

provides the organisation, equipment, materials and the<br />

logical procedure for learning. And it can do little more.<br />

Beca.use after all, the onus does rest on the student.<br />

This is one idea on the subject. I would be grateful to<br />

hear other views.<br />

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •<br />

the<br />

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 13<br />

The disappointments, and the tedious hours of crushing<br />

are all repaid by the excitement of discovery; and along with<br />

this comes a new humility towards nature, and a new respect<br />

for .the ancient craft of potting: It is still not an exact science<br />

even after more than four thousand years of progress, and<br />

it may be that the best discaveries are yet to be made if we<br />

try not just that which has been proven, but also that which<br />

might work.<br />

37

AN EFFICIENT ELECTRIC KILN<br />

by Arthur Higg.<br />

Electric kilns available to studio potters usually rely for<br />

their insulation on relatively low quality fire bricks and<br />

hence are unnecessarily bulky and expensive to operate.<br />

Better insulating materials are available which, though<br />

more fragile than brick, are quite suitable for use in the<br />

smaller sizes, and make possible the construction of kilns<br />

lighter in weight and more economical to' operate than those<br />

built from more conventional materials. Our interest in the<br />

design of an efficient electric kiln arose from the need for<br />

one of worthwhile dimensions which would be capable af<br />

reaching stoneware temperatures where only a single phase<br />

15 amp. supply was available. The construction of a kiln of<br />

this type is within the capabilities af an average handyman,<br />

although help from an electrician will be necessary in the<br />

final stages of connecting-up. The notes which follow<br />

indicate trye requirements for a kiln of internal dimensions<br />