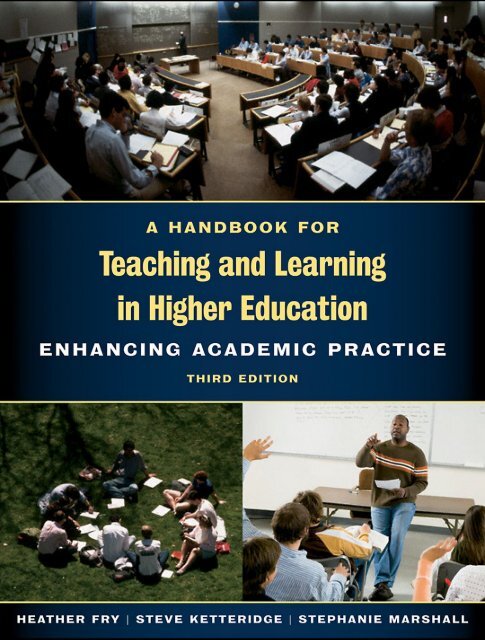

A Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Enhancing academic and Practice

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

A <strong>H<strong>and</strong>book</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

A <strong>H<strong>and</strong>book</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong> is sensitive to the compet<strong>in</strong>g<br />

dem<strong>and</strong>s of teach<strong>in</strong>g, research <strong>and</strong> scholarship, <strong>and</strong> <strong>academic</strong> management. Aga<strong>in</strong>st these<br />

contexts, the book focuses on develop<strong>in</strong>g professional <strong>academic</strong> skills <strong>for</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Deal<strong>in</strong>g with the rapid expansion of the use of technology <strong>in</strong> higher education <strong>and</strong><br />

widen<strong>in</strong>g student diversity, this fully updated <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ed edition <strong>in</strong>cludes new<br />

material on, <strong>for</strong> example, e-learn<strong>in</strong>g, lectur<strong>in</strong>g to large groups, <strong>for</strong>mative <strong>and</strong> summative<br />

assessment, <strong>and</strong> supervis<strong>in</strong>g research students.<br />

Part 1 exam<strong>in</strong>es teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> supervis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education, focus<strong>in</strong>g on a range of<br />

approaches <strong>and</strong> contexts.<br />

Part 2 exam<strong>in</strong>es teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> discipl<strong>in</strong>e-specific areas <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>cludes new chapters on<br />

eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g, economics, law, <strong>and</strong> the creative <strong>and</strong> per<strong>for</strong>m<strong>in</strong>g arts.<br />

Part 3 considers approaches to demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> enhanc<strong>in</strong>g practice.<br />

Written to support the excellence <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g required to br<strong>in</strong>g about learn<strong>in</strong>g of the<br />

highest quality, this will be essential read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> all new lecturers, particularly anyone<br />

tak<strong>in</strong>g an accredited course <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education, as well as all<br />

those experienced lecturers who wish to improve their teach<strong>in</strong>g. Those work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> adult<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> education development will also f<strong>in</strong>d it a particularly useful resource.<br />

Heather Fry is the found<strong>in</strong>g Head of the Centre <strong>for</strong> <strong>Education</strong>al Development at Imperial<br />

College London.<br />

Steve Ketteridge is Director of <strong>Education</strong>al <strong>and</strong> Staff Development at Queen Mary,<br />

University of London.<br />

Stephanie Marshall is Director of Programmes at the Leadership Foundation <strong>for</strong> <strong>Higher</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> is currently Visit<strong>in</strong>g Professor at Queen Mary, University of London.

A <strong>H<strong>and</strong>book</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

Enhanc<strong>in</strong>g Academic <strong>Practice</strong><br />

Third edition<br />

Edited by<br />

Heather Fry<br />

Steve Ketteridge<br />

Stephanie Marshall

First edition published 1999<br />

Second edition published 2003<br />

by Routledge<br />

This edition published 2009<br />

by Routledge<br />

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016<br />

Simultaneously published <strong>in</strong> the UK<br />

by Routledge<br />

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Ab<strong>in</strong>gdon, Oxon OX14 4RN<br />

Routledge is an impr<strong>in</strong>t of the Taylor <strong>and</strong> Francis Group, an <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>ma bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

This edition published <strong>in</strong> the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008.<br />

“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s<br />

collection of thous<strong>and</strong>s of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.t<strong>and</strong>f.co.uk.”<br />

© 2003 <strong>in</strong>dividual contributors; 2009 Taylor & Francis<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repr<strong>in</strong>ted or reproduced<br />

or utilised <strong>in</strong> any <strong>for</strong>m or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means,<br />

now known or hereafter <strong>in</strong>vented, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g photocopy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> record<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

or <strong>in</strong> any <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation storage or retrieval system, without permission<br />

<strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g from the publishers.<br />

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or<br />

registered trademarks, <strong>and</strong> are used only <strong>for</strong> identification <strong>and</strong> explanation<br />

without <strong>in</strong>tent to <strong>in</strong>fr<strong>in</strong>ge.<br />

Library of Congress Catalog<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Publication Data<br />

A h<strong>and</strong>book <strong>for</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education : enhanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>academic</strong><br />

practice / [edited by] Heather Fry, Steve Ketteridge, Stephanie Marshall.–3rd ed.<br />

p. cm.<br />

Includes bibliographical references <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dex.<br />

1. College teach<strong>in</strong>g–<strong>H<strong>and</strong>book</strong>s, manuals, etc. 2. College teachers. 3. Lecture method<br />

<strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g. I. Fry, Heather. II. Ketteridge, Steve. III. Marshall, Stephanie. IV. Title:<br />

<strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education.<br />

LB2331.H3145 2008<br />

378,1′25–dc22<br />

2008009873<br />

ISBN 0-203-89141-4 Master e-book ISBN<br />

ISBN 10: 0–415–43463–7 (hbk)<br />

ISBN 10: 0–415–43464–5 (pbk)<br />

ISBN 10: 0–203–89141–4 (ebk)<br />

ISBN 13: 978–0–415–43463–8 (hbk)<br />

ISBN 13: 978–0–415–43464–5 (pbk)<br />

ISBN 13: 978–0–203–89141–4 (ebk)

Contents<br />

List of illustrations<br />

Notes on contributors<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Foreword<br />

viii<br />

x<br />

xvii<br />

xviii<br />

Part 1 <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, supervis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education 1<br />

1 A user’s guide 3<br />

Heather Fry, Steve Ketteridge <strong>and</strong> Stephanie Marshall<br />

2 Underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g student learn<strong>in</strong>g 8<br />

Heather Fry, Steve Ketteridge <strong>and</strong> Stephanie Marshall<br />

3 Encourag<strong>in</strong>g student motivation 27<br />

Sherria L. Hosk<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Stephen E. Newstead<br />

4 Plann<strong>in</strong>g teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g: curriculum design <strong>and</strong> development 40<br />

Lorra<strong>in</strong>e Stefani<br />

5 Lectur<strong>in</strong>g to large groups 58<br />

Ann Morton<br />

6 <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> small groups 72<br />

S<strong>and</strong>ra Griffiths<br />

7 E-learn<strong>in</strong>g – an <strong>in</strong>troduction 85<br />

Sam Brenton<br />

❘<br />

v<br />

❘

vi<br />

❘<br />

Contents<br />

8 <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> employability: knowledge is not the only outcome 99<br />

Paul<strong>in</strong>e Kneale<br />

9 Support<strong>in</strong>g student learn<strong>in</strong>g 113<br />

David Gosl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

10 Assess<strong>in</strong>g student learn<strong>in</strong>g 132<br />

L<strong>in</strong> Norton<br />

11 Supervis<strong>in</strong>g projects <strong>and</strong> dissertations 150<br />

Stephanie Marshall<br />

12 Supervis<strong>in</strong>g research students 166<br />

Steve Ketteridge <strong>and</strong> Morag Shiach<br />

13 <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> quality, st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>and</strong> enhancement 186<br />

Judy McKimm<br />

14 Evaluat<strong>in</strong>g courses <strong>and</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g 198<br />

Dai Hounsell<br />

Part 2 <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the discipl<strong>in</strong>es 213<br />

15 <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the discipl<strong>in</strong>es 215<br />

Denis Berthiaume<br />

16 Key aspects of learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> experimental sciences 226<br />

Ian Hughes <strong>and</strong> T<strong>in</strong>a Overton<br />

17 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> mathematics <strong>and</strong> statistics 246<br />

Joe Kyle <strong>and</strong> Peter Kahn<br />

18 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g 264<br />

John Dickens <strong>and</strong> Carol Arlett<br />

19 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> comput<strong>in</strong>g science 282<br />

Gerry McAllister <strong>and</strong> Sylvia Alex<strong>and</strong>er<br />

20 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> arts, humanities <strong>and</strong><br />

social sciences 300<br />

Philip W. Mart<strong>in</strong>

Contents<br />

❘<br />

vii<br />

21 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> languages 323<br />

Carol Gray <strong>and</strong> John Klapper<br />

22 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the visual arts 345<br />

Alison Shreeve, Shân Ware<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> L<strong>in</strong>da Drew<br />

23 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g: enhanc<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

legal education 363<br />

Tracey Varnava <strong>and</strong> Julian Webb<br />

24 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> account<strong>in</strong>g, bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

<strong>and</strong> management 382<br />

Ursula Lucas <strong>and</strong> Peter Mil<strong>for</strong>d<br />

25 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> economics 405<br />

Liz Barnett<br />

26 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> dentistry 424<br />

Adam Feather <strong>and</strong> Heather Fry<br />

27 Key aspects of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> midwifery 449<br />

Pam Parker <strong>and</strong> Della Freeth<br />

Part 3 Enhanc<strong>in</strong>g personal practice 467<br />

28 Enhanc<strong>in</strong>g personal practice: establish<strong>in</strong>g teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g credentials 469<br />

Heather Fry <strong>and</strong> Steve Ketteridge<br />

29 <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> excellence as a vehicle <strong>for</strong> career progression 485<br />

Stephanie Marshall <strong>and</strong> Gus Penn<strong>in</strong>gton<br />

Glossary 499<br />

Index 513

Illustrations<br />

FIGURES<br />

2.1 The Kolb <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Cycle 15<br />

4.1 The logical model of curriculum development 52<br />

4.2 A modification to Cowan’s earlier model 53<br />

4.3 Views of the curriculum 54<br />

11.1 Supervisor–supervisee relationship <strong>in</strong> project supervision 153<br />

14.1 Sources <strong>and</strong> methods of feedback 202<br />

14.2 The evaluation cycle 208<br />

15.1 Model of discipl<strong>in</strong>e-specific pedagogical knowledge (DPK) <strong>for</strong><br />

university teach<strong>in</strong>g 219<br />

24.1 The ‘<strong>for</strong>–about’ spectrum <strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess education 384<br />

24.2 Shift<strong>in</strong>g the focus along the ‘<strong>for</strong>–about’ spectrum 391<br />

26.1 PBL at St George’s 430<br />

TABLES<br />

2.1 <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> styles 19<br />

2.2 Classification of <strong>academic</strong> knowledge 20<br />

3.1 Reasons <strong>for</strong> study<strong>in</strong>g 28<br />

3.2 Percentage of students agree<strong>in</strong>g with questions on the ASSIST scale 32<br />

3.3 Motivational generalisations <strong>and</strong> design pr<strong>in</strong>ciples 35–36<br />

4.1 The University of Auckl<strong>and</strong>: graduate profile 42<br />

5.1 Emphasis<strong>in</strong>g the structure of lectures us<strong>in</strong>g signals <strong>and</strong> clues 62<br />

7.1 Hypothetical teach<strong>in</strong>g situations <strong>and</strong> possible e-learn<strong>in</strong>g responses 89–90<br />

9.1 Questions students ask themselves 118<br />

10.1 Characteristics of grades A, B <strong>and</strong> C 140<br />

12.1 University of East Anglia: full-time research degrees 168<br />

❘<br />

viii<br />

❘

Illustrations<br />

❘<br />

ix<br />

12.2 Doctoral qualifications obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the UK, 2001 to 2005 170<br />

15.1 Dimensions associated with components of the knowledge base<br />

<strong>for</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g 219–221<br />

15.2 Dimensions associated with components of discipl<strong>in</strong>ary specificity 221<br />

15.3 Dimensions associated with components of the personal<br />

epistemology 222<br />

23.1 Skills <strong>and</strong> cognitive levels assessed by law coursework <strong>and</strong><br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ations 376<br />

24.1 A critical read<strong>in</strong>g framework <strong>for</strong> empirical <strong>academic</strong> papers 397<br />

28.1A The UK Professional St<strong>and</strong>ards Framework 470<br />

28.1B Areas of activity, knowledge <strong>and</strong> values with<strong>in</strong> the Framework 471

Contributors<br />

THE EDITORS<br />

Heather Fry is the found<strong>in</strong>g Head of the Centre <strong>for</strong> <strong>Education</strong>al Development at<br />

Imperial College London. After teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> lectur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Nigeria she worked at the<br />

Institute of <strong>Education</strong>, London, <strong>and</strong> the Barts <strong>and</strong> Royal London School of Medic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

<strong>and</strong> Dentistry at Queen Mary, University of London. She teaches, researches <strong>and</strong><br />

publishes on <strong>academic</strong> practice <strong>in</strong> higher education. Her particular passions are how<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g, curriculum organisation <strong>and</strong> manipulation of ‘context’ can support <strong>and</strong><br />

exp<strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g, especially <strong>in</strong> medical <strong>and</strong> surgical education. She has also been<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the development of several <strong>in</strong>novative programmes <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a Master’s<br />

<strong>in</strong> Surgical <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> another <strong>in</strong> University <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>.<br />

Steve Ketteridge is the first Director of <strong>Education</strong>al <strong>and</strong> Staff Development at Queen<br />

Mary, University of London. His <strong>academic</strong> career began with a university lectureship<br />

<strong>in</strong> microbiology. Subsequently he established the Postgraduate Certificate <strong>in</strong> Academic<br />

<strong>Practice</strong> at Queen Mary <strong>and</strong> has developed strategy <strong>in</strong> areas such as learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g, skills <strong>and</strong> employability. He is a key reference po<strong>in</strong>t on supervision of<br />

doctoral students <strong>in</strong> science <strong>and</strong> eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> advises universities <strong>and</strong> research<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutes across the UK. Recently he has been <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational work on the<br />

development of per<strong>for</strong>mance <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>for</strong> university teach<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Stephanie Marshall is Director of Programmes at the Leadership Foundation <strong>for</strong> <strong>Higher</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong>, where she has worked s<strong>in</strong>ce 2003, <strong>and</strong> is currently Visit<strong>in</strong>g Professor at<br />

Queen Mary, University of London. Prior to this, she worked at the University of York,<br />

where she taught <strong>and</strong> researched <strong>in</strong> the Department of <strong>Education</strong>al Studies, mov<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on to set up the university’s first Staff Development Office. Subsequently she became<br />

the Provost of Goodricke College, <strong>and</strong> worked <strong>in</strong> the Centre <strong>for</strong> Leadership <strong>and</strong><br />

Management. She has published widely.<br />

❘<br />

x<br />

❘

Contributors<br />

❘<br />

xi<br />

THE AUTHORS<br />

Sylvia Alex<strong>and</strong>er is Director of Access <strong>and</strong> Distributed <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> at the University of<br />

Ulster. She has a wide knowledge of current practice <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g, learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

assessment result<strong>in</strong>g from previous <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> a variety of national <strong>in</strong>itiatives<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Academy.<br />

Carol Arlett is the Manager <strong>for</strong> the Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g Subject Centre <strong>and</strong> oversees the Centre’s<br />

range of activities that aim to provide subject-specific support <strong>for</strong> eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>academic</strong>s. She has a particular <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> employer engagement <strong>and</strong> skills development.<br />

Liz Barnett is Director of the London School of Economics (LSE) <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

Centre. At the LSE she has collaborated with colleagues both <strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g graduate<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g assistants <strong>and</strong> encourag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>novatory teach<strong>in</strong>g approaches. She previously<br />

worked at the University of Southampton <strong>and</strong> has lectured on <strong>in</strong>ternational health.<br />

Denis Berthiaume is Director of the Centre <strong>for</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> at the University<br />

of Lausanne, Switzerl<strong>and</strong>. His research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude discipl<strong>in</strong>e-specific teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

higher education, reflective practice <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> the assessment of learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

higher education.<br />

Sam Brenton is Head of E-<strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> at Queen Mary, University of London. He is<br />

particularly <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> the social uses <strong>and</strong> effects of new media <strong>and</strong> virtual worlds.<br />

He has been an author, broadcaster, critic, journalist, poet <strong>and</strong> educational developer.<br />

John Dickens is Director of the Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g Subject Centre. He is also Professor of<br />

Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Education</strong>, Associate Dean (<strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>) <strong>for</strong> the Faculty of Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong><br />

Director of the Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g Centre <strong>for</strong> Excellence <strong>in</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (CETL) at<br />

Loughborough University. He has 25 years of teach<strong>in</strong>g experience <strong>in</strong> civil <strong>and</strong> structural<br />

eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g design <strong>and</strong> received a National <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Fellowship <strong>in</strong> 2006.<br />

L<strong>in</strong>da Drew is the Dean of Academic Development at the University of the Arts London,<br />

UK. L<strong>in</strong>da is found<strong>in</strong>g editor of the journal Art, Design <strong>and</strong> Communication <strong>in</strong> <strong>Higher</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong>. She is also a Fellow <strong>and</strong> Vice-chair of the Design Research Society <strong>and</strong> Vicechair<br />

of the Group <strong>for</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Art <strong>and</strong> Design.<br />

Adam Feather is a Consultant Geriatrician at Newham University Hospital Trust <strong>and</strong> a<br />

Senior Lecturer <strong>in</strong> Medical <strong>Education</strong> at Barts <strong>and</strong> The London, Queen Mary’s School<br />

of Medic<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> Dentistry. He is married to the most underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g woman <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world <strong>and</strong> has a Weapon of Mass Destruction, aged 4.<br />

Della Freeth is Professor of Professional <strong>and</strong> Interprofessional <strong>Education</strong> with<strong>in</strong><br />

City Community <strong>and</strong> Health Sciences, contribut<strong>in</strong>g to the CETL on Cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong><br />

Communication Skills developed jo<strong>in</strong>tly by City University <strong>and</strong> Queen Mary,<br />

University of London.

xii<br />

❘<br />

Contributors<br />

David Gosl<strong>in</strong>g has written widely on topics relat<strong>in</strong>g to learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher<br />

education <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> applied philosophy. Formerly Head of <strong>Education</strong>al Development at<br />

the University of East London, he is now Visit<strong>in</strong>g Research Fellow at the University of<br />

Plymouth. He works as an <strong>in</strong>dependent consultant with many universities <strong>in</strong> the UK<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternationally.<br />

Carol Gray is Senior Lecturer <strong>in</strong> Modern Languages <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, University of<br />

Birm<strong>in</strong>gham. She is <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the development of <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>-service tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong><br />

modern languages <strong>and</strong> publishes on a range of related topics.<br />

S<strong>and</strong>ra Griffiths was <strong>for</strong>merly a Senior Lecturer <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> at the University of Ulster.<br />

She has wide experience of support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> research<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> of<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g, teach<strong>in</strong>g, review<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> consult<strong>in</strong>g globally on postgraduate certificates<br />

<strong>for</strong> university teachers. She is President of the All-Irel<strong>and</strong> Society <strong>for</strong> <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> a member of the International Council <strong>for</strong> <strong>Education</strong>al Development. In 2005 she<br />

was awarded a National <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Fellowship.<br />

Sherria L. Hosk<strong>in</strong>s is a Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal Lecturer at the University of Portsmouth where she is<br />

Course Leader <strong>for</strong> the B.Sc. Psychology <strong>and</strong> an operational member of the ExPERT<br />

(Excellence <strong>in</strong> Professional Development through <strong>Education</strong>, Research <strong>and</strong><br />

Technology) CETL. In 2004 she was awarded a University <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

Fellowship. She is an active researcher, focus<strong>in</strong>g on social cognitive aspects of learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

success, from school to university <strong>and</strong> beyond.<br />

Dai Hounsell is Professor of <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong> at the University of Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh <strong>and</strong><br />

previously Director of the Centre of <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> Assessment at that<br />

university. He publishes <strong>and</strong> advises widely on teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g matters.<br />

Ian Hughes is a National <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Fellow, Professor of Pharmacology <strong>Education</strong>,<br />

University of Leeds, <strong>and</strong> has directed the <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Academy Centre <strong>for</strong><br />

Bioscience, as well as other EU <strong>and</strong> UK projects, <strong>for</strong> example develop<strong>in</strong>g educational<br />

software.<br />

Peter Kahn is <strong>Education</strong>al Developer <strong>in</strong> the Centre <strong>for</strong> Lifelong <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> at the University<br />

of Liverpool. He publishes widely on teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education, <strong>and</strong><br />

is co-editor (with Joe Kyle) of Effective <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Mathematics <strong>and</strong> its<br />

Applications, also published by Routledge.<br />

John Klapper is a Professor <strong>and</strong> Director of the Centre <strong>for</strong> Modern Languages, University<br />

of Birm<strong>in</strong>gham, where he also teaches <strong>in</strong> German Studies. He is a National <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

Fellow <strong>and</strong> publishes widely on various aspects of <strong>for</strong>eign language pedagogy <strong>and</strong><br />

teacher development.<br />

Paul<strong>in</strong>e Kneale is Professor of Applied Hydrology with <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

Geography at the University of Leeds. She became a National <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Fellow <strong>in</strong> 2002<br />

<strong>and</strong> is well known <strong>in</strong> the UK <strong>for</strong> her work on curriculum development <strong>and</strong> student<br />

employability.

Contributors<br />

❘<br />

xiii<br />

Joe Kyle was <strong>for</strong>merly Senior Lecturer <strong>and</strong> Director of <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

the School of Mathematics <strong>and</strong> Statistics at Birm<strong>in</strong>gham University. Mathematics<br />

coord<strong>in</strong>ator <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Academy Mathematics, Statistics <strong>and</strong><br />

Operational Research Network, he is an editor of <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Mathematics <strong>and</strong> its<br />

Applications.<br />

Ursula Lucas is Professor of Account<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Education</strong> at Bristol Bus<strong>in</strong>ess School, University<br />

of the West of Engl<strong>and</strong>. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests are <strong>in</strong> the development of a reflective<br />

capacity with<strong>in</strong> higher education <strong>and</strong> workplace learn<strong>in</strong>g. In 2001 she was awarded a<br />

National <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Fellowship.<br />

Gerry McAllister holds a B.Sc. <strong>and</strong> M.Sc. <strong>in</strong> Electronic Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Ph.D. <strong>in</strong><br />

Computer Science. He is currently Director of the Subject Centre <strong>for</strong> In<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>and</strong><br />

Computer Sciences at the University of Ulster, where he is Professor of Computer<br />

Science <strong>and</strong> Head of the School of Comput<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Mathematics.<br />

Judy McKimm works at the Centre <strong>for</strong> Medical <strong>and</strong> Health Sciences <strong>Education</strong>,<br />

University of Auckl<strong>and</strong>, New Zeal<strong>and</strong>. She was <strong>for</strong>merly a Visit<strong>in</strong>g Professor at the<br />

University of Bed<strong>for</strong>dshire. She has a long-st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> quality<br />

enhancement.<br />

Philip W. Mart<strong>in</strong> is Pro Vice-chancellor of De Mont<strong>for</strong>t University. He has responsibility<br />

<strong>for</strong> Academic Quality <strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong> all <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> across the university. His remit<br />

also <strong>in</strong>cludes the student experience. He is a Professor of English <strong>and</strong> was <strong>for</strong>merly<br />

Director of the English Subject Centre (<strong>for</strong> the teach<strong>in</strong>g of English <strong>in</strong> universities) at<br />

Royal Holloway, University of London.<br />

Peter Mil<strong>for</strong>d is Interim Associate Director of <strong>Education</strong> <strong>for</strong> the South West Strategic<br />

Health Authority. Be<strong>for</strong>e rejo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the NHS <strong>in</strong> 2002, he was a Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal Lecturer<br />

<strong>in</strong> Account<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> F<strong>in</strong>ance at Bristol Bus<strong>in</strong>ess School, University of the West of<br />

Engl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Ann Morton is Head of Staff Development at Aston University. She was previously<br />

Programme Director <strong>for</strong> the Postgraduate Certificate <strong>in</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> at the<br />

University of Birm<strong>in</strong>gham <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ues to teach on the similar programme <strong>for</strong> new<br />

lecturers at Aston.<br />

Stephen E. Newstead is Professor of Psychology at the University of Plymouth, though<br />

recently he has ventured <strong>in</strong>to management territory as Dean, Deputy Vice-Chancellor<br />

<strong>and</strong> even Vice-Chancellor. Back <strong>in</strong> the days when he had time to do research, his<br />

<strong>in</strong>terests focused on cognitive psychology <strong>and</strong> the psychology of higher education,<br />

especially student assessment.<br />

L<strong>in</strong> Norton is a National <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Fellow (2007), Professor of Pedagogical Research <strong>and</strong><br />

Dean of <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> at Liverpool Hope University. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude student assessment which she pursues through her role as Research Director<br />

of the Write Now CETL.

xiv ❘<br />

Contributors<br />

T<strong>in</strong>a Overton is Professor of Chemistry <strong>Education</strong> at the University of Hull <strong>and</strong> Director<br />

of the <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Academy Physical Sciences Centre. She has published on<br />

critical th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, context-based learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> problem solv<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Pam Parker spent many years <strong>in</strong> the School of Nurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Midwifery, City University,<br />

focus<strong>in</strong>g on learn<strong>in</strong>g, teach<strong>in</strong>g, assess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> curriculum development. She is<br />

now co-director of CEAP (Centre <strong>for</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> Academic <strong>Practice</strong>) at City<br />

University.<br />

Gus Penn<strong>in</strong>gton now works as a consultant <strong>in</strong> the areas of change management <strong>and</strong><br />

quality enhancement. He is Visit<strong>in</strong>g Professor at Queen Mary, University of London,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a <strong>for</strong>mer chief executive of a national agency <strong>for</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g professional<br />

development throughout the UK higher education sector.<br />

Morag Shiach is Vice-pr<strong>in</strong>cipal (<strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>) at Queen Mary, University of<br />

London. She has extensive experience of supervis<strong>in</strong>g research students <strong>and</strong> of<br />

exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g doctoral dissertations <strong>in</strong> English <strong>and</strong> cultural history. She has published<br />

widely on cultural history, particularly <strong>in</strong> the modernist period.<br />

Alison Shreeve is Director of the Creative <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> CETL at the University of<br />

the Arts London, UK. She is currently engaged <strong>in</strong> doctoral research <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

experience of the practitioner tutor <strong>in</strong> art <strong>and</strong> design.<br />

Lorra<strong>in</strong>e Stefani is Director of the Centre <strong>for</strong> Academic Development at the University<br />

of Auckl<strong>and</strong>, New Zeal<strong>and</strong>. Her particular <strong>in</strong>terests are curriculum design <strong>and</strong><br />

development <strong>for</strong> a twenty-first-century university education; <strong>in</strong>novative strategies <strong>for</strong><br />

assessment of student learn<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional strategies to promote student<br />

engagement.<br />

Tracey Varnava is Associate Director of the UK Centre <strong>for</strong> Legal <strong>Education</strong>, the <strong>Higher</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong> Academy Subject Centre <strong>for</strong> Law based at the University of Warwick. Be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

mov<strong>in</strong>g to Warwick, she was a Lecturer <strong>in</strong> Law at the University of Leicester.<br />

Shân Ware<strong>in</strong>g is Dean of <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Development at the University of the<br />

Arts London, UK, where she leads the Centre <strong>for</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Art <strong>and</strong><br />

Design. She is also a Fellow <strong>and</strong> Co-Chair of the Staff <strong>and</strong> <strong>Education</strong>al Development<br />

Association.<br />

Julian Webb is Director of the UK Centre <strong>for</strong> Legal <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> Professor of Legal<br />

<strong>Education</strong> at the University of Warwick, where he also leads the UK’s only Master’s<br />

degree <strong>in</strong> Legal <strong>Education</strong>.<br />

Case study authors<br />

Chapter authors who have written case studies have not been re-listed. National<br />

attribution has been assigned if outside the UK. Academic titles <strong>and</strong> departments can be<br />

found with<strong>in</strong> the case studies.

Contributors<br />

❘<br />

xv<br />

Julie Attenborough, City University<br />

Juan Baeza, now K<strong>in</strong>g’s College London<br />

Simon Bates, University of Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh<br />

Mick Beeby, University of the West of Engl<strong>and</strong><br />

Simon Belt, University of Plymouth<br />

Paul Blackmore, now K<strong>in</strong>g’s College London<br />

Chris Bolsmann, Aston University<br />

Melanie Bowles, University of the Arts London<br />

Jim Boyle, University of Strathclyde<br />

Margaret Bray, London School of Economics <strong>and</strong> Political Science<br />

David Bristow, Pen<strong>in</strong>sula Medical School<br />

Peter Bullen, University of Hert<strong>for</strong>dshire<br />

Liz Burd, University of Durham<br />

Christopher Butcher, University of Leeds<br />

Rachael Carkett, now at University of Teesside<br />

Hugh Cartwright, Ox<strong>for</strong>d University<br />

Marion E. Cass, Carleton College, USA<br />

Tudor Ch<strong>in</strong>nah, Pen<strong>in</strong>sula Medical School<br />

Elizabeth Davenport, Queen Mary, University of London<br />

Matt Davies, Aston University<br />

Russell Davies, Pen<strong>in</strong>sula Medical School<br />

Val Dimmock, City University<br />

Roberto Di Napoli, Imperial College London<br />

Carol<strong>in</strong>e Elliott, University of Lancaster<br />

John Fothergill, University of Leicester<br />

Ann Gilroy, University of Auckl<strong>and</strong>, NZ<br />

Christopher Goldsmith, De Mont<strong>for</strong>t University<br />

Anne Goodman, South West <strong>and</strong> Wales Hub (Cardiff University)<br />

Nuala Gregory, University of Auckl<strong>and</strong>, NZ<br />

Louise Grisoni, University of the West of Engl<strong>and</strong><br />

Mick Healey, University of Gloucestershire<br />

Ia<strong>in</strong> Henderson, Napier University<br />

Sarah Henderson, University of Auckl<strong>and</strong>, NZ<br />

Siobhán Holl<strong>and</strong>, Royal Holloway, University of London<br />

Desmond Hunter, University of Ulster<br />

Andrew Irel<strong>and</strong>, Bournemouth University<br />

Tony Jenk<strong>in</strong>s, University of Leeds<br />

Mike Joy, University of Warwick<br />

Sally Kift, University of Queensl<strong>and</strong>, Australia

xvi<br />

❘<br />

Contributors<br />

Chris Lawn, Queen Mary, University of London<br />

Jonathan Leape, London School of Economics <strong>and</strong> Political Science<br />

David Lefevre, Imperial College London<br />

David Lewis, University of Leeds<br />

Ian Light, City University<br />

Gary Lock, University of Bath<br />

Lynne MacAlp<strong>in</strong>e, McGill University, Canada, <strong>and</strong> University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

George MacDonald Ross, University of Leeds<br />

Peter McCrorie, St George’s Medical School, University of London<br />

Neil McLean, London School of Economics <strong>and</strong> Political Science<br />

Karen Mattick, Pen<strong>in</strong>sula Medical School<br />

Carol<strong>in</strong>e Mills, University of Gloucestershire<br />

Ebrahim Mohamed, Imperial College London<br />

Clare Morris, University of Bed<strong>for</strong>dshire<br />

Office of the Independent Adjudicator <strong>for</strong> <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

Fiona Oldham, Napier University<br />

James Oldham, Pen<strong>in</strong>sula Medical School<br />

Alan Patten, Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton University, USA<br />

Ben Pont<strong>in</strong>, University of the West of Engl<strong>and</strong><br />

Steve Probert, Bus<strong>in</strong>ess, Management, Account<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> F<strong>in</strong>ance Subject Centre (Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Brookes University)<br />

Sarah Qu<strong>in</strong>ton, Ox<strong>for</strong>d Brookes University<br />

Lisa Reynolds, City University<br />

Sarah Richardson, Warwick University<br />

Andrew Rothwell, Coventry University<br />

Mark Russell, University of Hert<strong>for</strong>dshire<br />

Henry S. Rzepa, Imperial College London<br />

Andrew Scott, London School of Economics <strong>and</strong> Political Science<br />

Stephen Shute, University of Birm<strong>in</strong>gham<br />

Alan Simpson, City University<br />

Teresa Smallbone, Ox<strong>for</strong>d Brookes University<br />

Adrian Smith, Southampton University<br />

Simon Ste<strong>in</strong>er, <strong>for</strong>merly University of Birm<strong>in</strong>gham<br />

Stan Taylor, University of Durham<br />

Tanya Tierney, Imperial College London<br />

Guglielmo Volpe, London Metropolitan University<br />

Digby Warren, London Metropolitan University<br />

Charlotte K. Williams, Imperial College London<br />

Matthew Williamson, Queen Mary, University of London

Acknowledgements<br />

The editors wish to acknowledge all those who have assisted <strong>in</strong> the production of the<br />

third edition of this h<strong>and</strong>book. We are especially grateful, as always, to our team of expert<br />

contribut<strong>in</strong>g authors <strong>and</strong> those who have supplied the case studies that enrich the text.<br />

A special word of thanks is due to Mrs Nicole Nathan without whose organisational<br />

skills <strong>and</strong> help this book would have been much longer <strong>in</strong> com<strong>in</strong>g to fruition.<br />

We particularly wish to acknowledge the role of Professor Gus Penn<strong>in</strong>gton <strong>in</strong><br />

support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> encourag<strong>in</strong>g the editors at all stages <strong>in</strong> the creation of the h<strong>and</strong>book <strong>and</strong><br />

most recently <strong>in</strong> the production of this third edition.<br />

Heather Fry<br />

Steve Ketteridge<br />

Stephanie Marshall<br />

❘<br />

xvii<br />

❘

Foreword<br />

It is a pleasure to write this <strong>for</strong>eword to the third edition of the highly successful<br />

<strong>H<strong>and</strong>book</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong>. While its contributors are ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

British <strong>and</strong> there are places where it necessarily addresses a specifically British context,<br />

this is a collection which has genu<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>ternational appeal <strong>and</strong> relevance. For, across<br />

much of the globe, the world of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education is be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

shaped by similar phenomena: a larger, more dem<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> more diverse student<br />

body, a pervasive language of quality <strong>and</strong> accountability, rapidly chang<strong>in</strong>g technological<br />

possibilities yet uneven levels of student familiarity with them, more dem<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

arrangements with governments, <strong>and</strong> expectations by students <strong>and</strong> employers that<br />

graduates will be equipped <strong>for</strong> rapidly chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> globalis<strong>in</strong>g workplaces.<br />

This is a h<strong>and</strong>book which offers higher education professionals both sage advice on<br />

the essentials of effective teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> research-based reflection on emerg<strong>in</strong>g trends. It<br />

is a precious collection of core chapters on lectur<strong>in</strong>g to large groups, teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> small groups, teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> employability, assessment, <strong>and</strong> supervision of<br />

research theses. At the same time, there are chapters on e-learn<strong>in</strong>g, effective student<br />

support, <strong>and</strong> ways of provid<strong>in</strong>g evidence <strong>for</strong> accredited teach<strong>in</strong>g certificates <strong>and</strong><br />

promotion, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g use of teach<strong>in</strong>g portfolios. Specialists from the<br />

creative <strong>and</strong> per<strong>for</strong>m<strong>in</strong>g arts <strong>and</strong> humanities through bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>and</strong> law to the physical<br />

<strong>and</strong> health sciences will benefit from discipl<strong>in</strong>e-specific reflections on challenges <strong>in</strong><br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g, learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g. Specific case studies, actual examples of successful<br />

practice, <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ks to helpful websites add to the <strong>H<strong>and</strong>book</strong>’s usefulness.<br />

This is thus a volume to which young <strong>academic</strong>s will turn <strong>for</strong> lucid, practical advice on<br />

the essentials of effective classroom practice, while their experienced colleagues will f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

it a rich compendium of challenges to refresh their knowledge <strong>and</strong> reth<strong>in</strong>k their<br />

assumptions. Teachers <strong>and</strong> students all over the world will have cause to be grateful to<br />

the co-editors Heather Fry, Steve Ketteridge <strong>and</strong> Stephanie Marshall, <strong>and</strong> to the score of<br />

contributors they have expertly assembled. Never be<strong>for</strong>e has there been such a need <strong>for</strong><br />

sound but stimulat<strong>in</strong>g advice <strong>and</strong> reflection on teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education, <strong>and</strong> this is<br />

a splendid contribution to meet<strong>in</strong>g that need.<br />

Professor Peter McPhee,<br />

Provost,<br />

University of Melbourne,<br />

Australia<br />

❘<br />

xviii<br />

❘

Part 1<br />

<strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, supervis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher<br />

education

1<br />

A user’s guide<br />

Heather Fry, Steve Ketteridge<br />

<strong>and</strong> Stephanie Marshall<br />

SETTING THE CONTEXT OF ACADEMIC PRACTICE<br />

This book starts from the premise that the roles of those who teach <strong>in</strong> higher education<br />

are complex <strong>and</strong> multifaceted. <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> is recognised as be<strong>in</strong>g only one of the roles<br />

that readers of this book will be undertak<strong>in</strong>g. It recognises <strong>and</strong> acknowledges that<br />

<strong>academic</strong>s have contractual obligations to pursue excellence <strong>in</strong> several directions, most<br />

notably <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g, research <strong>and</strong> scholarship, supervision, <strong>academic</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>and</strong><br />

management <strong>and</strong>, <strong>for</strong> many, ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> provision of service <strong>in</strong> a<br />

profession (such as teach<strong>in</strong>g or nurs<strong>in</strong>g). Academic practice is a term that encompasses<br />

all these facets.<br />

The focus of this book is on teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> the supervision of students. The purpose of<br />

both of these activities, <strong>and</strong> all that is associated with them (<strong>for</strong> example, curriculum<br />

organisation <strong>and</strong> assessment), is to facilitate learn<strong>in</strong>g, but as our focus is on what the<br />

teacher/supervisor does to contribute to this, we have stressed the role of the teacher <strong>in</strong><br />

both the title <strong>and</strong> the text of this h<strong>and</strong>book. However, effective teach<strong>in</strong>g (<strong>and</strong> supervision,<br />

assessment, plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> so on) has to be predicated on an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of how<br />

students learn; the objective of the activities is to br<strong>in</strong>g about learn<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> there has to<br />

be <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>and</strong> knowledge about learners’ needs <strong>for</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g to be successful.<br />

The authors recognise the fast pace of change <strong>in</strong> higher education. The past decade<br />

has seen cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> student numbers, further <strong>in</strong>ternationalisation of the<br />

student population, <strong>and</strong> wider diversity <strong>in</strong> the prior educational experience of students.<br />

All these factors have placed yet more pressure on resources, requirements <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>come<br />

generation, improved flexibility <strong>in</strong> modes of study <strong>and</strong> delivery (particularly <strong>in</strong> distance<br />

<strong>and</strong> e-learn<strong>in</strong>g) <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g scrut<strong>in</strong>y <strong>in</strong> relation to quality <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ards. Commonly,<br />

<strong>academic</strong>s will now work with students who are not only based on campus but also at<br />

a distance. A further challenge fac<strong>in</strong>g the higher education sector is the expectation<br />

to prepare students more carefully <strong>for</strong> the world of work. For many students the need to<br />

take on paid employment dur<strong>in</strong>g term time is a f<strong>in</strong>ancial reality. Other themes with<strong>in</strong><br />

❘<br />

3<br />

❘

4 ❘<br />

<strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, supervis<strong>in</strong>g, learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>clude the pressure to respond to local <strong>and</strong> national student op<strong>in</strong>ion surveys<br />

of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> the total learn<strong>in</strong>g experience, compliance with the Bologna Declaration<br />

<strong>and</strong> extend<strong>in</strong>g the work <strong>and</strong> impact of universities out <strong>in</strong>to the local community.<br />

PURPOSE OF THIS BOOK<br />

This book is <strong>in</strong>tended primarily <strong>for</strong> relatively <strong>in</strong>experienced teachers <strong>in</strong> higher education.<br />

Established lecturers <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> explor<strong>in</strong>g recent developments <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g, learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> assessment will also f<strong>in</strong>d it valuable. It will be of <strong>in</strong>terest to a range of staff work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> higher education, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those work<strong>in</strong>g with communications <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation<br />

technology, library <strong>and</strong> technical staff, graduate teach<strong>in</strong>g assistants <strong>and</strong> various types of<br />

researchers. It has much to offer those work<strong>in</strong>g outside higher education (<strong>for</strong> example,<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>icians) who have roles <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g. Those jo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g universities after hav<strong>in</strong>g<br />

worked <strong>in</strong> a different university tradition/context (perhaps <strong>in</strong> a different country), or<br />

from bus<strong>in</strong>ess, <strong>in</strong>dustry or the professions, will f<strong>in</strong>d this volume a useful <strong>in</strong>troduction to<br />

current practice <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> universities <strong>in</strong> a wide range of countries.<br />

Many of the authors work, or have worked, <strong>in</strong> the UK (<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> other countries), <strong>and</strong> the<br />

UK experience is <strong>for</strong>egrounded <strong>in</strong> the text, but there are many ideas that are transferable,<br />

albeit perhaps with a slightly different emphasis.<br />

The book is <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>med by best practice from many countries <strong>and</strong> types of <strong>in</strong>stitutions<br />

about teach<strong>in</strong>g, learn<strong>in</strong>g, assessment <strong>and</strong> course design, <strong>and</strong> is underp<strong>in</strong>ned by<br />

appropriate reference to research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. The focus is primarily (but not exclusively) on<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g at undergraduate level. A particular strength of this book is that it reviews<br />

generic issues <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g that will be common to most practitioners, <strong>and</strong><br />

also explores, separately, practices <strong>in</strong> a range of major discipl<strong>in</strong>es. Importantly these two<br />

themes are l<strong>in</strong>ked <strong>in</strong> a dedicated chapter (15).<br />

It is likely that those <strong>in</strong> higher education tak<strong>in</strong>g university teach<strong>in</strong>g programmes or<br />

certificates or diplomas <strong>in</strong> <strong>academic</strong> practice will f<strong>in</strong>d the book useful <strong>and</strong> thought<br />

provok<strong>in</strong>g. It supports those <strong>in</strong> the UK whose university teach<strong>in</strong>g programme is l<strong>in</strong>ked<br />

to ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g national professional recognition through obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a fellowship or associate<br />

fellowship of the <strong>Higher</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Academy (HEA).<br />

The third edition of the book has been revised <strong>and</strong> updated. It now better reflects the<br />

chang<strong>in</strong>g world of higher education <strong>in</strong> the UK <strong>and</strong> beyond. It also <strong>in</strong>cludes new research<br />

<strong>and</strong> publications, <strong>in</strong>corporates case studies based on contemporary practice <strong>and</strong> considers<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g across a broader range of discipl<strong>in</strong>es. The authors have carefully<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrated l<strong>in</strong>ks <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation from the UK HEA Subject Centres.<br />

The book draws together the accumulated knowledge <strong>and</strong> wisdom of many experienced<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluential practitioners <strong>and</strong> researchers. Authors come from a range of<br />

discipl<strong>in</strong>ary backgrounds <strong>and</strong> from a range of higher educational <strong>in</strong>stitutions. They have<br />

taken care <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g to avoid overuse of jargon, but to <strong>in</strong>troduce key term<strong>in</strong>ology, <strong>and</strong><br />

to make the text readily accessible to staff from all discipl<strong>in</strong>es. The book aims to take a<br />

scholarly <strong>and</strong> rigorous approach, while ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a user-friendly <strong>for</strong>mat.

A user’s guide<br />

❘<br />

5<br />

The book has been written on the premise that readers strive to extend <strong>and</strong> enhance<br />

their practice. It endeavours to offer a start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>for</strong> consider<strong>in</strong>g teach<strong>in</strong>g, provok<strong>in</strong>g<br />

thought, giv<strong>in</strong>g rationales <strong>and</strong> examples, encourag<strong>in</strong>g reflective practice, <strong>and</strong> prompt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

considered actions to enhance one’s teach<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

For the purposes of this book the terms ‘<strong>academic</strong>’, ‘lecturer’, ‘teacher’ <strong>and</strong> ‘tutor’ are<br />

used <strong>in</strong>terchangeably <strong>and</strong> should be taken to <strong>in</strong>clude anyone engaged <strong>in</strong> the support of<br />

student learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education.<br />

NAVIGATING THE HANDBOOK<br />

Each chapter is written so that it can be read <strong>in</strong>dependently of the others, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> any<br />

order. Readers can easily select <strong>and</strong> prioritise, accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>terest, although Chapter 2<br />

should be early essential read<strong>in</strong>g. The book has three major parts <strong>and</strong> a glossary.<br />

Part 1: <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, supervis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education<br />

This, the <strong>in</strong>troductory chapter, describes the features of the book <strong>and</strong> how to use it.<br />

Chapter 2 lays essential foundations by putt<strong>in</strong>g an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of how students learn<br />

at the heart of teach<strong>in</strong>g. Part 1 has 12 further chapters, each of which explores a major facet<br />

of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>/or learn<strong>in</strong>g. Each is considered from a broad perspective rather than<br />

adopt<strong>in</strong>g the view or emphasis of a particular discipl<strong>in</strong>e. These chapters address most of<br />

the repertoire essential to teach<strong>in</strong>g, supervis<strong>in</strong>g, curriculum development, assessment<br />

<strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the student experience of higher education.<br />

Part 2: <strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the discipl<strong>in</strong>es<br />

This section opens with a chapter that considers <strong>and</strong> explores how teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher<br />

education draws on knowledge of three areas, namely knowledge about one’s discipl<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

generic pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>and</strong> ideas about teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g (Part 1) <strong>and</strong> specific paradigms<br />

<strong>and</strong> objectives particular to teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> one’s own discipl<strong>in</strong>ary area (Part 2).<br />

It suggests that as experience <strong>and</strong> knowledge of teach<strong>in</strong>g grows, so are teachers more<br />

<strong>in</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ed/able to l<strong>in</strong>k these areas together. Subsequent chapters draw out, <strong>for</strong> several<br />

major discipl<strong>in</strong>ary group<strong>in</strong>gs, the characteristic features of teach<strong>in</strong>g, learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

assessment. These chapters are most useful when read <strong>in</strong> conjunction with the chapters<br />

<strong>in</strong> Part 1. They also provide the opportunity <strong>for</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a particular<br />

discipl<strong>in</strong>e to explore successful practices associated with other discipl<strong>in</strong>es that might be<br />

adapted to their own use.

6 ❘<br />

<strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, supervis<strong>in</strong>g, learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Part 3: Enhanc<strong>in</strong>g personal practice<br />

This section is concerned with how teachers can learn, explore, develop, enhance <strong>and</strong><br />

demonstrate their teach<strong>in</strong>g expertise. It describes frameworks <strong>and</strong> tools <strong>for</strong> professional<br />

development <strong>and</strong> demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g experience <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g, be it as part of a programme to<br />

enhance <strong>in</strong>dividual practice or about susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g career development.<br />

Glossary<br />

The f<strong>in</strong>al section is a glossary of educational acronyms <strong>and</strong> technical terms. This may be<br />

used <strong>in</strong> conjunction with read<strong>in</strong>g the chapters or (as many of our previous readers have<br />

found) separately. In the chapters the mean<strong>in</strong>g of words or terms <strong>in</strong> bold may be looked<br />

up <strong>in</strong> the glossary.<br />

DISTINCTIVE FEATURES<br />

Interrogat<strong>in</strong>g practice<br />

Chapters feature one or more <strong>in</strong>stances where readers are <strong>in</strong>vited to consider aspects of<br />

their own <strong>in</strong>stitution, department, course, students or practice. This is done by pos<strong>in</strong>g<br />

questions to the reader under the head<strong>in</strong>g ‘Interrogat<strong>in</strong>g practice’. This feature has several<br />

purposes. First, to encourage readers to audit their practice with a view to enhancement.<br />

Second, to challenge readers to exam<strong>in</strong>e critically their conceptions of teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

workplace practice. Third, to ensure that readers are familiar with their <strong>in</strong>stitutional <strong>and</strong><br />

departmental policies <strong>and</strong> practices. Fourth, to give teachers the opportunity to develop<br />

the habit of reflect<strong>in</strong>g on practice. Readers are free to choose how, or if, they engage with<br />

these <strong>in</strong>terrogations.<br />

Case studies<br />

A strength of the book is that each chapter conta<strong>in</strong>s case studies. These exemplify issues,<br />

practices <strong>and</strong> research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs mentioned <strong>in</strong> the body of the chapters. The examples are<br />

drawn from a wealth of <strong>in</strong>stitutions, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g everyday practice of authors <strong>and</strong> their<br />

colleagues, to demonstrate how particular approaches are used effectively.<br />

FURTHER READING<br />

Each chapter has its own reference section <strong>and</strong> suggested further read<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g current<br />

web-based resources.

A user’s guide<br />

❘<br />

7<br />

IN CONCLUSION<br />

This third edition of the h<strong>and</strong>book builds upon <strong>and</strong> updates the previous editions, while<br />

reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the features which have contributed to the success <strong>and</strong> wide usage of the book.<br />

There are new chapters which <strong>in</strong>troduce further expert authors <strong>and</strong> provide a greater<br />

wealth of case study material. The editors are confident that this approach, comb<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

with a reflection of the chang<strong>in</strong>g world of higher education (especially <strong>in</strong> the UK), offers<br />

a worthwhile h<strong>and</strong>book <strong>for</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g as part of <strong>academic</strong> practice.

2<br />

Underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

student learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Heather Fry, Steve Ketteridge<br />

<strong>and</strong> Stephanie Marshall<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

It is un<strong>for</strong>tunate, but true, that some <strong>academic</strong>s teach students without hav<strong>in</strong>g much<br />

<strong>for</strong>mal knowledge of how students learn. Many lecturers know how they learnt/learn<br />

best, but do not necessarily consider how their students learn <strong>and</strong> if the way they teach<br />

is predicated on enabl<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g to happen. Nor do they necessarily have the concepts<br />

to underst<strong>and</strong>, expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> articulate the process they sense is happen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their<br />

students.<br />

<strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> is about how we perceive <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> the world, about mak<strong>in</strong>g mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(Marton <strong>and</strong> Booth, 1997). But ‘learn<strong>in</strong>g’ is not a s<strong>in</strong>gle th<strong>in</strong>g; it may <strong>in</strong>volve master<strong>in</strong>g<br />

abstract pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g proofs, remember<strong>in</strong>g factual <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation, acquir<strong>in</strong>g<br />

methods, techniques <strong>and</strong> approaches, recognition, reason<strong>in</strong>g, debat<strong>in</strong>g ideas, or<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g behaviour appropriate to specific situations; it is about change.<br />

Despite many years of research <strong>in</strong>to learn<strong>in</strong>g, it is not easy to translate this knowledge<br />

<strong>in</strong>to practical implications <strong>for</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g. There are no simple answers to the questions<br />

‘how do we learn?’ <strong>and</strong> ‘how as teachers can we br<strong>in</strong>g about learn<strong>in</strong>g?’ This is partly<br />

because education deals with specific purposes <strong>and</strong> contexts that differ from each other<br />

<strong>and</strong> with students as people, who are diverse <strong>in</strong> all respects, <strong>and</strong> ever chang<strong>in</strong>g. Not<br />

everyone learns <strong>in</strong> the same way, or equally readily about all types of material. The<br />

discipl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> level of material to be learnt have an <strong>in</strong>fluence. Students br<strong>in</strong>g different<br />

backgrounds <strong>and</strong> expectations to learn<strong>in</strong>g. Our knowledge about the relationship<br />

between teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>in</strong>complete <strong>and</strong> the attitudes <strong>and</strong> actions of both parties<br />

affect the outcome, but we do know enough to make some firm statements about types<br />

of action that will usually be helpful <strong>in</strong> enabl<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g to happen. In this chapter some<br />

of the major learn<strong>in</strong>g theories that are relevant to higher education are <strong>in</strong>troduced. In the<br />

discipl<strong>in</strong>e of education a theory is someth<strong>in</strong>g built from research evidence, which may<br />

have explanatory power; much educational research is not about prov<strong>in</strong>g or disprov<strong>in</strong>g<br />

theories, but about creat<strong>in</strong>g them from research data.<br />

❘<br />

8<br />

❘

Underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g student learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

❘<br />

9<br />

Increas<strong>in</strong>gly teach<strong>in</strong>g takes place at a distance or electronically rather than face-to-face,<br />

but the theories <strong>and</strong> ideas outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> this chapter still need to be considered.<br />

Motivation <strong>and</strong> assessment both play a large part <strong>in</strong> student learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education<br />

<strong>and</strong> these topics are considered <strong>in</strong> more detail <strong>in</strong> Chapters 3 <strong>and</strong> 10.<br />

This chapter is <strong>in</strong>tended to give only a general overview of some key ideas about<br />

student learn<strong>in</strong>g. It describes some of the common learn<strong>in</strong>g models <strong>and</strong> theories relevant<br />

to higher education, presents case studies <strong>in</strong> which lecturers relate their teach<strong>in</strong>g to some<br />

of these ideas, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicates broad implications of these ideas <strong>for</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

We hope readers will consider the ideas, <strong>and</strong> use those that are helpful <strong>in</strong> organis<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> enhanc<strong>in</strong>g their teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their discipl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> context.<br />

Interrogat<strong>in</strong>g practice<br />

As you read this chapter, note down, from what it says about learn<strong>in</strong>g, the<br />

implications <strong>for</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> your discipl<strong>in</strong>e. When you reach the last section<br />

of the chapter, compare your list with the general suggestions you will f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

there.<br />

MAJOR VIEWS OF LEARNING<br />

In psychology there are several schools of thought about how learn<strong>in</strong>g takes place, <strong>and</strong><br />

various categorisations of these. Rationalism (or idealism) is one such school, or pole, of<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g theory still with some vogue. It is based on the idea of a biological plan be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

existence that unfolds <strong>in</strong> very determ<strong>in</strong>ed directions. Chomsky was a <strong>for</strong>emost member<br />

of this pole. Associationism, a second pole, centres on the idea of <strong>for</strong>m<strong>in</strong>g associations<br />

between stimuli <strong>and</strong> responses. Pavlov <strong>and</strong> Sk<strong>in</strong>ner belong to this pole. Further details<br />

may be found <strong>in</strong> Richardson (1985). In the twenty-first century cognitive <strong>and</strong> social<br />

theories are those used most widely, with constructivism be<strong>in</strong>g the best known.<br />

Many ideas about learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the early twentieth century tended to consider the<br />

development of the <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong> isolation, but by the 1920s <strong>and</strong> 1930s ideas look<strong>in</strong>g at<br />

the <strong>in</strong>fluence of the wider context <strong>in</strong> which learn<strong>in</strong>g occurs <strong>and</strong> at emotional <strong>and</strong> social<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>and</strong> affects became more common. These ideas cont<strong>in</strong>ue to ga<strong>in</strong> ground <strong>and</strong><br />

some are mentioned later <strong>in</strong> this chapter.<br />

Constructivism<br />

Most contemporary psychologists use constructivist theories of vary<strong>in</strong>g types to expla<strong>in</strong><br />

how human be<strong>in</strong>gs learn. The idea rests on the notion of cont<strong>in</strong>uous build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

amend<strong>in</strong>g of structures <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>d that ‘hold’ knowledge. These structures are known

10 ❘<br />

<strong>Teach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, supervis<strong>in</strong>g, learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

as schemata. As new underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gs, experiences, actions <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation are<br />

assimilated <strong>and</strong> accommodated the schemata change. Unless schemata are changed,<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g will not occur. <strong>Learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (whether <strong>in</strong> cognitive, affective, <strong>in</strong>terpersonal or<br />

psychomotor doma<strong>in</strong>s) is said to <strong>in</strong>volve a process of <strong>in</strong>dividual trans<strong>for</strong>mation. Thus<br />

people actively construct their knowledge (Biggs <strong>and</strong> Moore, 1993).<br />