Work Package 2 - Universidade de Santiago de Compostela

Work Package 2 - Universidade de Santiago de Compostela

Work Package 2 - Universidade de Santiago de Compostela

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

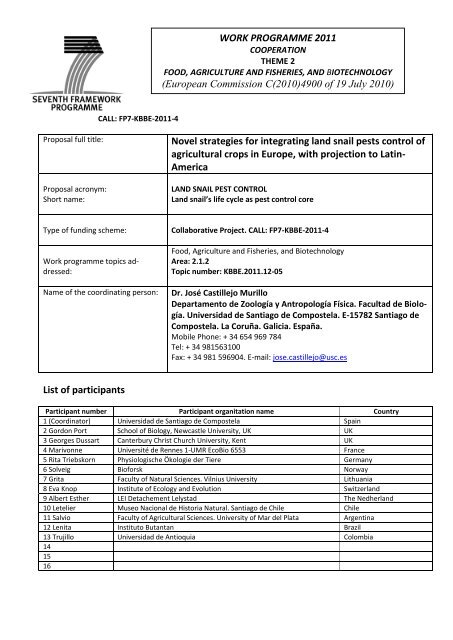

CALL: FP7-KBBE-2011-4<br />

Proposal full title: Novel strategies for integrating land snail pests control of<br />

agricultural crops in Europe, with projection to Latin-<br />

America<br />

Proposal acronym:<br />

Short name:<br />

Type of funding scheme:<br />

<strong>Work</strong> programme topics addressed:<br />

LAND SNAIL PEST CONTROL<br />

Land snail’s life cycle as pest control core<br />

Collaborative Project. CALL: FP7-KBBE-2011-4<br />

Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, and Biotechnology<br />

Area: 2.1.2<br />

Topic number: KBBE.2011.12-05<br />

Name of the coordinating person: Dr. José Castillejo Murillo<br />

Departamento <strong>de</strong> Zoología y Antropología Física. Facultad <strong>de</strong> Biología.<br />

Universidad <strong>de</strong> <strong>Santiago</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Compostela</strong>. E-15782 <strong>Santiago</strong> <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>Compostela</strong>. La Coruña. Galicia. España.<br />

Mobile Phone: + 34 654 969 784<br />

Tel: + 34 981563100<br />

Fax: + 34 981 596904. E-mail: jose.castillejo@usc.es<br />

List of participants<br />

WORK PROGRAMME 2011<br />

COOPERATION<br />

THEME 2<br />

FOOD, AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES, AND BIOTECHNOLOGY<br />

(European Commission C(2010)4900 of 19 July 2010)<br />

Participant number Participant organitation name Country<br />

1 (Coordinator) Universidad <strong>de</strong> <strong>Santiago</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Compostela</strong> Spain<br />

2 Gordon Port School of Biology, Newcastle University, UK UK<br />

3 Georges Dussart Canterbury Christ Church University, Kent UK<br />

4 Marivonne Université <strong>de</strong> Rennes 1-UMR EcoBio 6553 France<br />

5 Rita Triebskorn Physiologische Ökologie <strong>de</strong>r Tiere Germany<br />

6 Solveig Bioforsk Norway<br />

7 Grita Faculty of Natural Sciences. Vilnius University Lithuania<br />

8 Eva Knop Institute of Ecology and Evolution Switzerland<br />

9 Albert Esther LEI Detachement Lelystad The Nedherland<br />

10 Letelier Museo Nacional <strong>de</strong> Historia Natural. <strong>Santiago</strong> <strong>de</strong> Chile Chile<br />

11 Salvio Faculty of Agricultural Sciences. University of Mar <strong>de</strong>l Plata Argentina<br />

12 Lenita Instituto Butantan Brazil<br />

13 Trujillo Universidad <strong>de</strong> Antioquia Colombia<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

2

Novel strategies for integrating land-snail pest control of agricultural crops in<br />

Europe, with projection to Latin-America<br />

TITLE: Novel strategies for integrating land-snail pests control of agricultural crops in Europe, with projection to<br />

Latin-America.<br />

1: Scientific and technical quality, relevant to the topics addressed by the call<br />

1.1 Concept and objectives<br />

To introduce in a series of traditional and ecological crops, new strategies for the integrated land snail pest<br />

control. These strategies are based in the <strong>de</strong>ep knowledge of the pest´s biology and ecology, so that the<br />

abundance and the activity periods can be predicted to elaborate an integrated pest control system and take<br />

<strong>de</strong>cisions that can be applied in every <strong>de</strong>velop phase (juvenile, adult, senile or eggs). Thanks to this the farmer will<br />

know when to apply the traditional molluscici<strong>de</strong>s (to <strong>de</strong>stroy the land snails), when to use ovicidal molluscici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

(to <strong>de</strong>stroy the egg lays), when to apply the biological control through parasite nemato<strong>de</strong>s or when to use the<br />

trap-plants; and all this strategy will be regulated by the statistical mo<strong>de</strong>l witch predict the activity. To <strong>de</strong>velop<br />

this integrated control methods it will be necessary:<br />

1. To know the biotic and a biotic factor that <strong>de</strong>scribe the land snails biological cycle in different areas of<br />

Europe and Latin-America, to elaborate the control method.<br />

2. To know the specific land snails´ diet with the objective of finding the most attractive plant species to use<br />

them as trap-plants.<br />

3. To un<strong>de</strong>rstand the activity in function of the environment biotic and a biotic variables, with the aiming of<br />

<strong>de</strong>veloping an effective abundance and activity statistical prediction method.<br />

4. To search plants with bio pestici<strong>de</strong> activity for be used as bio-molluscici<strong>de</strong>s and bio-ovici<strong>de</strong>s against land<br />

snail and its eggs.<br />

5. To know the ovicidal potential of the usual non residual agrochemicals to use them as molluscici<strong>de</strong>sovici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

in crops.<br />

6. To know the ovicidal potential of cattle’s and swine’s slurries as molluscici<strong>de</strong>s-ovici<strong>de</strong>s in ecological<br />

farming.<br />

7. To search in each study areas of Latin-America a parasite nemato<strong>de</strong> (Phasmarhabdities alike) to use it as a<br />

biological control method against land snails.<br />

8. To <strong>de</strong>liver to the horticultural industry an effective integrated crop management strategies, low chemical<br />

and biological protecting methods against land snails.<br />

9. To <strong>de</strong>liver to the ecological farming effective integrated packages methods based on cattle and swine<br />

manure and plant traps, to protect the crops against land snail pests.<br />

With these strategies we are settling the basis for an integrated control method, to achieve a more rentable<br />

crop due to; having less plant damages, less pestici<strong>de</strong>s use, and a more respectful farming with the environment<br />

and the wild fauna. The land snail pest problem in Europe and Latin-America is increasing every day due the<br />

commercial globalization. The most dangerous land snail species in Europe are: Arion lusitancicus, Deroceras<br />

retiuclatum, Lehamnnia marginata, Milax gagates, Criptophalus aspersus and Theba pisana among others. The<br />

90% of the land snail species that are pest in Latin-America are introduced species from Europe and other<br />

countries, this species proliferate indiscriminately because of the absence of natural predators, such as Acanthina<br />

fúlica, Deroceras reticulatum, Milax gagates, Lhemannia marginata, Arion intermedius, Criptophalus aspersus….<br />

In some Caribbean regions native land snail species cause important damages, such is the case of Veronicella<br />

genus in Mexico and Cuba.<br />

1

Scientific and technical objectives <strong>de</strong>tailed <strong>de</strong>scription<br />

This project requires the application of novel control strategies to control native or introduced land snail<br />

pests in crops that can be used in any agricultural pest. With the strategies proposed here we can anticipate to<br />

the damages caused by the land snail pests, due the application of a preventive method even before damages<br />

appear on the crops.<br />

Our strategies are based on:<br />

1. To un<strong>de</strong>rstand the land snails biological cycle in the crops study areas.<br />

2. To un<strong>de</strong>rstand the land snails activity in function of the climatic variables and the crop type.<br />

3. To <strong>de</strong>stroy the land snail´s egg-lays thanks to the plant extracts and non residual standard<br />

agrochemicals collateral effect.<br />

4. To rationalize standard molluscici<strong>de</strong>s consumption in standard farming.<br />

5. To introduce cattle and swine manure and trap-plants as control methods in organic farming.<br />

6. To un<strong>de</strong>rstand the collateral effects of the products used in this integrated pest control methods.<br />

The un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of the biological cycle is very important, because we attempt to use the molluscici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

before damages appear. With the knowledge of the biological cycle we will know which time of the year is<br />

juvenile, adult or senile, we will know when the egg-lays are done, and in other words, we will know the sizes,<br />

structure and dynamics of their populations. The information provi<strong>de</strong>d by the biological cycle is important to<br />

implement this new strategy, as these molluscici<strong>de</strong>s must be applied when the population <strong>de</strong>nsity is lower and<br />

when there are fewer egg-lays in the soil. With this we obtain an optimal effectiveness <strong>de</strong>stroying the egg-lays<br />

through ovicidal and also killing gastropods. By applying less molluscici<strong>de</strong>s we save money and minimize the si<strong>de</strong><br />

effects on the environment.<br />

Knowing the diet of land snails in the study areas will give us information on the possible use of trap-plants,<br />

to evaluate and estimate the damage that they actually produce on crops. By studying the stomach contents of a<br />

specified number of land snails we can know their preferences, in previous research we found that plants that<br />

had a low abundance in the environment, appeared with high frequency in the stomach of land snails, this means<br />

that they have positive selection for this type of plants. These plants can be used as trap-plants to protect<br />

vegetable crops <strong>de</strong>terring land snails to eat the trap-plants. It is a very useful strategy in organic farming.<br />

Knowing the activity of terrestrial gastropods in terms of climatic variables and crop phenology is required<br />

to <strong>de</strong>velop a statistical for activity prediction. With this mo<strong>de</strong>l we can predict with 24-48 beforehand the activity,<br />

and provi<strong>de</strong> the farmer information that land snails will be active, and thus may apply the traditional<br />

molluscici<strong>de</strong>s at the right time, getting a greater effectiveness using smaller amount of molluscici<strong>de</strong>s, leading to<br />

saving resources and reducing si<strong>de</strong> effects on plants, soil and wildlife.<br />

So far we have been talking about traditional molluscici<strong>de</strong>s. The tradiotional molluscici<strong>de</strong>s (metal<strong>de</strong>hy<strong>de</strong>,<br />

carbamate, iron sulphate, phasmarhadities...) are inten<strong>de</strong>d to kill the individuals, in other words, kill the<br />

terrestrial gastropods leaving intact the land snail´s egg-lays in the soil.<br />

There is a growing body of evi<strong>de</strong>nce to suggest that in the past 4-5 <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s there has been an excessive<br />

dumping of chemical toxins on the soil. As a result the soil has become barren and ground water toxic, in many<br />

places. Contrast this with organic inputs that are safe, non toxic, and cost much less. 'Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s' are certain<br />

types of pestici<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong>rived from such natural materials as animals, plants, bacteria, and certain minerals. Benefits<br />

of biopestici<strong>de</strong>s inclu<strong>de</strong> effective control of insects, plant diseases and weeds, as well as human and<br />

environmental safety. Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s also play an important role in providing pest management tools in areas<br />

where pestici<strong>de</strong> resistance, niche markets and environmental concerns limit the use of chemical pestici<strong>de</strong><br />

products. To find plants extract with molluscicidal and ovicidal activity against land snails and their eggs are<br />

original and promising.<br />

In each country, agricultural authorities allow a number of non residual agrochemicals for different uses<br />

and for different purposes, can be fertilizers, herbici<strong>de</strong>s, acarici<strong>de</strong>s, fungici<strong>de</strong>s, etc... These products have gone<br />

through a series of tests to be authorized. In previous research we have tested non residual agrochemicals to see<br />

if they had the potential to <strong>de</strong>stroy the land snail´s egg-lays, and many of them had as si<strong>de</strong> effect the egg-lays<br />

killing. Basing on these assumptions each partner must make a test series with non residual agrochemicals<br />

approved in their country, to discover which one or ones have a higher ovicidal power at the lowest concentration<br />

2

in the shortest time. In organic farming the use of synthetic chemicals such as fertilizers, pestici<strong>de</strong>s, antibiotics,<br />

etc.., it´s forbid<strong>de</strong>n, with the objective of preserving the environment, maintaining or enhancing soil fertility and<br />

provi<strong>de</strong> food with all its natural properties. Fertilizers that can be used in these kinds of crops can be of two types,<br />

green fertilizers or livestock manure. In previous research we found that certain concentration of swine and cattle<br />

manure had ovicidal action on terrestrial gastropod egg-lays. Therefore each partner will have to do tests to<br />

discover the type and concentration of manure that has higher ovicidal power against the land snail´s egg-lays in<br />

their study areas.<br />

Finding a new parasite-nemato<strong>de</strong> with a biological cycle like Phasmorhadities hermaphrodita is crucial to<br />

have a new tool for biological land snail pests control in agriculture in Latin-America, as the European variety has<br />

problems at certain soil temperatures. The task to find European zoo parasitic nemato<strong>de</strong> was ma<strong>de</strong> in previous<br />

97- UE - Project.<br />

As a consequence the of traditional and organic farmers are going to get a series of useful tools for land<br />

snail pests and, first they are going to have a new control strategy based on the application of the ovicidalmolluscici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

at the correct time, <strong>de</strong>termined by the life cycle of the terrestrial gastropods, and not by the crop<br />

phenology. It will be explained which chemicals they need to <strong>de</strong>stroy land snail´s egg-lays. Through the predictive<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>l, the farmers will have the information necessary to know which day and a time terrestrial gastropods will<br />

be active, thus apply the traditional molluscici<strong>de</strong>s at the right, time, place and amount. This information must be<br />

transmitted through scientific meetings, counselling State Agricultural Agencies and through web pages of the<br />

State Servers.<br />

3

Compliance with the objectives of the work programme and its priorities<br />

This project can <strong>de</strong>finitely solve the problem of land snail pests in agriculture that has been globalized by the<br />

reform of the European Common Agricultural Policy and which it is forced to fulfil in the countries from which we<br />

import agricultural products.<br />

This project is related to THEME 2 (Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, and Biotechnology), Area 2.1.2<br />

KBBE.2010.1.2-05 "Integrated pest management in farming systems of major importance for Europe" out of the<br />

7th Framework Program of Cooperation (FP7 Cooperation <strong>Work</strong> Program), and our project fits in perfectly in the<br />

topics (issues) of integrated pest control (management) (In the context of Integrated Pest Management - IPM-) in<br />

particular (specifically) can be said that:<br />

1. It inclu<strong>de</strong>s preventive measures such as, molluscici<strong>de</strong>s application in the more labile phases of the life cycle<br />

of terrestrial gastropods and when there is less <strong>de</strong>nsity of population and eggs in the soil, which generally<br />

coinci<strong>de</strong>s with (periods in which) (times when) there is nothing planted on farms .<br />

2. The <strong>de</strong>sign of this strategy is based on the study of the biological cycle of pests and the study of their activity<br />

in terms of biotic and abiotic variables of the environment, representing perfect control and more accurate<br />

information to take preventive measures.<br />

3. With this strategy control measures are applied at the right time, anticipating the emergence of the pest,<br />

which implies less molluscici<strong>de</strong> applied to achieve a better effect, besi<strong>de</strong>s the molluscici<strong>de</strong> is never next to<br />

plants, if the measures control are applied prior to planting. Our strategy is aimed at controlling or<br />

eradicating the pest to protect the crop, in other words, we use a preventive strategy.<br />

4. It is an integrated control based on the <strong>de</strong>cision-making through the statistical mo<strong>de</strong>l prediction. We only<br />

use low toxicity chemicals, we use the biological control of nemato<strong>de</strong>s through zooparasites, not to mention<br />

the use of trap plants to <strong>de</strong>ter terrestrial gastropods that attack crops or the use of swine and cattle manure<br />

as ovicidal all this applied at the time we enter the life cycle of the pest snail and the predictive mo<strong>de</strong>l.<br />

5. Con este proyecto estamos sentando las bases para que los agricultores cumplan la Directive 2009/128/EC of<br />

The European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a framework for Community action to<br />

achieve the sustainable use of pestici<strong>de</strong>s, según la cual by 14 December 2018 will be necessary to minimise the<br />

hazards and risks to health and environment from the use of pestici<strong>de</strong>s. Al finalizar este proyecto dispondremos <strong>de</strong> biomolusquicidas<br />

with molluscicida and ovicidal action. Syngenta and Bayer Companies are intrested in this WP.<br />

6. This strategy helped to reduce pestici<strong>de</strong> use on crops applying the necessary quantity at the right time, not<br />

introducing new chemicals in agricultural crops, but taking advantage of the farmers’ standard used non<br />

residual agrochemicals just giving it a different use or using the favourable si<strong>de</strong>-effects. Thereby <strong>de</strong>creasing<br />

the amount of toxic agents that may be harmful to humans and to wildlife and soil.<br />

7. This project combines "combine mo<strong>de</strong>lling and experimentation" because the entire strategy is based on<br />

the study of biological and ecological cycle of the pest, its dynamics, in or<strong>de</strong>r to achieve the greatest success<br />

of control with the least effort and with the least means.<br />

8. The risks of not succeeding in this project are limited, first all the partners who are part of the research<br />

group have <strong>de</strong>monstrated ability to perform all the tasks outlined in the <strong>Work</strong> <strong>Package</strong>s, and also the USC<br />

team that coordinates this project has an extensive experience in <strong>de</strong>veloping predictive mo<strong>de</strong>ls of activity of<br />

the snails and slugs in agricultural crops of Galicia (Spain) and in controlling pests in vegetable crops and<br />

vineyards and many others European partners have similar experience in similar fields. Given the<br />

globalization of tra<strong>de</strong>, over 90% of land snail species pests in Latin-America are of European origin, in other<br />

words, they are introduced species that we have been working with over 20 years.<br />

9. The balance between costs and benefits will always be positive because we will control the final shape of<br />

land snail pests in agriculture, and we will bring to the traditional and organic farmers to have a number of<br />

tools to obtain a more profitable crop and seeding time management, very respectful with the environment.<br />

10. Finally, all information obtained from this project and the control strategies are available for the farmer,<br />

either through meetings, workshops taught by the competent authorities or available through “on line”<br />

services were the farmers will resolve questions and provi<strong>de</strong> information of the pest activity.<br />

4

1.2 Progress beyond the state-of-the-art<br />

A escala mundial, los perjuicios económicos causados por los gasterópodos terrestres se han<br />

incrementado gracias a la globalización <strong>de</strong>l comercio lo que conlleva que se hable <strong>de</strong> especies <strong>de</strong> caracoles y<br />

babosas introducidas <strong>de</strong> un continente a otro, especies que al no tener <strong>de</strong>predadores específicos presenta un<br />

crecimiento poblacional exponencial. Mientras que algunos caracoles terrestres pue<strong>de</strong>n alcanzar el estatus <strong>de</strong><br />

plaga incluso en regiones relativamente áridas, las babosas resultan especialmente problemáticas en climas<br />

templados y lluviosos, pero aún en este caso, la magnitud <strong>de</strong> los daños causados por las babosas a los cultivos<br />

varía mucho a escala regional y <strong>de</strong> un año a otro (Port y Port, 1986). Muchos especialistas coinci<strong>de</strong>n en señalar<br />

que los daños ocasionados por los gasterópodos se han incrementado <strong>de</strong> forma muy significativa en las últimas 2<br />

ó 3 décadas, <strong>de</strong>bido a la conjunción <strong>de</strong> una serie <strong>de</strong> factores como la simplificación <strong>de</strong> las técnicas <strong>de</strong> cultivo<br />

(reducción <strong>de</strong>l laboreo, siembra directa), la reducción <strong>de</strong> las poblaciones <strong>de</strong> insectos <strong>de</strong>predadores por el uso <strong>de</strong><br />

insecticidas, o la utilización <strong>de</strong> nuevas varieda<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> cultivo más susceptibles al ataque <strong>de</strong> los gasterópodos<br />

(Hommay, 1995, 2002; Godan, 1999; Speiser, 2002). Por otro lado, la elevación <strong>de</strong> los estándares <strong>de</strong> calidad<br />

exigidos por los consumidores hace que la tolerancia <strong>de</strong>l mercado a productos dañados sea cada vez menor, lo<br />

que se traduce en una intensificación <strong>de</strong> las medidas <strong>de</strong> control <strong>de</strong> plagas.<br />

In recent years, the problems caused by land snails, especially the grey field slug (Deroceras reirulatum),<br />

the Spanish slug (Arion lusitanicus), the brown gar<strong>de</strong>n snail, Cryptomphalus (Helix = Cantareus) asperses,the<br />

white gar<strong>de</strong>n snail, Theba pisana and the greenhouse slug (Milax gagates), have increased dramatically, as<br />

illustrated by the 70-fold increase of molluscici<strong>de</strong> usage over the last 30 years as observed in Europe. These<br />

species are a serious pest of global economic importance (South, 1992) as they have adapted well to the varied<br />

environments to which they have been introduced around the world. A. lusitanicus is polyphagous and feeds on a<br />

range of crop species as well as dumped plant material and carcasses (Wittenberg 2005). In winter wheat alone,<br />

molluscici<strong>de</strong> use, including its application, is calculated to cost some £ 20 millions annually, yet the damage to<br />

seeds and seedlings is not reliable controlled (GLEN, 1989)<br />

Land snails reduce the vigour of some crops by killing seeds or seedling, by <strong>de</strong>sroying stems or growing<br />

points, or by reducing the leaf area. This may slow down crop <strong>de</strong>velopment and /or reduce yield. In other crops,<br />

the harvest is <strong>de</strong>valuated by feeding damage, mucus trails, faeces or presence of land snails. Land snail feeding<br />

may also initiate mould growth or rotting. Damage by land snails in not always easily distinguished from insect<br />

feeding. Clear, silvery mucus trails indicate land snail activity.<br />

In Swe<strong>de</strong>n the species is reported from strawberry fields and grain storage facilities. No overall<br />

assessment of the economic consequences of A. lusitanicus has been ma<strong>de</strong>, but the species contributes to<br />

damage on several horticultural crops (Fischer and Reisschütz 1999, Speiser et al. 2001). Furthermore, there are<br />

great impediments to human use of gar<strong>de</strong>ns as judged by the number of times this species make headlines in<br />

media (often un<strong>de</strong>r the alias “killer slug”)(Valovirta 2000).<br />

Strawberry growers in Norway have reported more than 50% loss in yield due to A. lusitanicus, but proper<br />

economic assessments have not been conducted yet. An example of a societal effect is that home owners have<br />

been known to sell their property and move to slug free areas. House prices may also be affected by the presence<br />

of this.<br />

In Central Europe, Limax maximus and Arion lusitanicus are the major pest slug species and most sales of<br />

molluscici<strong>de</strong> pellets in the home and gar<strong>de</strong>n market can be attributed to this species – this gives an indirect<br />

estimate of the damage they cause. Many of the European slugs and snails have been introduced to America,<br />

Australia and NZ and cause tremendous problems in their agricultural crops.<br />

Arion lusitanicus is polyphagous and feeds on a range of crop species as well as dumped plant material<br />

and carcasses (Wittenberg 2005). In Swe<strong>de</strong>n the species is reported from strawberry fields and grain storage<br />

facilities. No overall assessment of the economic consequences of A. lusitanicus has been ma<strong>de</strong>, but the species<br />

contributes to damage on several horticultural crops (Fischer and Reisschütz 1999, Speiser et al. 2001).<br />

Furthermore, there are great impediments to human use of gar<strong>de</strong>ns as judged by the number of times this<br />

species make headlines in media (often un<strong>de</strong>r the alias “killer slug”)(Valovirta 2000).<br />

5

El control <strong>de</strong> plagas <strong>de</strong> gasterópodos terrestres se realiza, <strong>de</strong> forma casi exclusiva, por medio <strong>de</strong> la<br />

aplicación <strong>de</strong> cebos (“pellets”) que contienen entre un 2% y un 8% <strong>de</strong> metal<strong>de</strong>hído o <strong>de</strong> carbamatos (Godan,<br />

1983, 1999; South, 1992; Garthwaite y Thomas, 1996; Bailey, 2002; Speiser, 2002). El principal productor mundial<br />

<strong>de</strong> metal<strong>de</strong>hído es la empresa suiza Lonza. El carbamato más utilizado en el control <strong>de</strong> plagas <strong>de</strong> gasterópodos<br />

terrestres es el metiocarbamato, cuya licencia <strong>de</strong> fabricación es propiedad <strong>de</strong> la empresa alemana Bayer. Ambos<br />

compuestos muestran una eficacia similar en lo que se refiere a su capacidad para reducir los daños causados por<br />

los gasterópodos a las plantas (Bailey, 2002), y también ambos presentan efectos negativos sobre las poblaciones<br />

<strong>de</strong> otros grupos <strong>de</strong> animales (South, 1992; Bailey, 2002). Buchs, Heimbach y Czarnecki (1989) han señalado la<br />

existencia <strong>de</strong> efectos negativos <strong>de</strong> los cebos molusquicidas con metal<strong>de</strong>hído sobre las poblaciones <strong>de</strong> algunos<br />

carábidos, y Bieri, Schweizer, Christensen y Daniel (1989) han documentado una reducción <strong>de</strong> la abundancia <strong>de</strong><br />

carábidos y estafilínidos tras la aplicación <strong>de</strong> cebos molusquicidas con metiocarbamato en pra<strong>de</strong>ras. Aunque en la<br />

actualidad todos los cebos molusquicidas incorporan pigmentos (generalmente azules) y otras sustancias para<br />

reducir el riesgo <strong>de</strong> ingestión por parte <strong>de</strong> mamíferos y aves, son frecuentes los casos <strong>de</strong> envenenamiento <strong>de</strong><br />

animales domésticos <strong>de</strong>bido al consumo <strong>de</strong> cebos molusquicidas (Bailey, 2002). A finales <strong>de</strong> los años 80, los cebos<br />

molusquicidas con carbamatos fueron prohibidos en muchos estados <strong>de</strong> Norteamérica, <strong>de</strong>bido a la elevada<br />

frecuencia <strong>de</strong> casos <strong>de</strong> envenenamiento <strong>de</strong> aves que se registraron (Sakovich, 1996). Tarrant y Westlake (1988)<br />

señalan que la utilización <strong>de</strong> cebos molusquicidas con metiocarbamato supone una seria amenaza para las<br />

poblaciones <strong>de</strong>l ratón <strong>de</strong> campo, Apo<strong>de</strong>mus sylvaticus (Linnaeus, 1758). Keymer, Gibson y Reynolds (1991)<br />

registraron elevadas concentraciones <strong>de</strong> acetal<strong>de</strong>hído (resultante <strong>de</strong> la <strong>de</strong>spolimerización <strong>de</strong>l metal<strong>de</strong>hído en el<br />

tubo digestivo) en erizos (Erinaceus europaeus (Linnaeus, 1758)) encontrados muertos en el campo, y Gemmeke<br />

(1997) observó síntomas <strong>de</strong> envenenamiento y casos <strong>de</strong> fallecimiento, en erizos alimentados con babosas que<br />

habían ingerido cebos con metiocarbamato.<br />

Product in<strong>de</strong>x by Active Substance Metal<strong>de</strong>hy<strong>de</strong>: B&Q Slug Killer Blue Mini Pellets, Barclay Metal<strong>de</strong>hy<strong>de</strong><br />

Dry, Barclay Tracker, Bio Slug Mini Pellets, BRITS, Doff Slugoids Slug Killer Blue Mini-Pellets, Escar-Go 6, Gastrotox<br />

Mini Slug Pellets, Gastrotox Slug Pellets, Goulding Slug Pellets, Greenfingers Slug Pellets, Hygeia Slug Pellets, Hytox<br />

Slug Pellets, Luxan Metal<strong>de</strong>hy<strong>de</strong> 5, Luxan Red 5, Metarex Green, Metarex RG, Molotov, Optimol, Pathfin<strong>de</strong>r Excel,<br />

Slug Clear, Slug Killer Blue Mini-Pellets, Slug Out, Slug Pellets, Slugit Xtra, Slugtox, Stockmaster Slug & Snail Killer<br />

In winter wheat, Brussels sprouts and rape crops, molluscici<strong>de</strong> use, including its application, is calculated<br />

to cost some £ 50 million annually in the United Kingdom, yet the damage to seed and seedling is not reliable<br />

controlled.<br />

Pestici<strong>de</strong>s sales in Europe are increasing. Levels of usage vary between countries. These profiles are part of<br />

an on-going series in Pestici<strong>de</strong>s News that will cover all of Europe. Sources: Oppenheimer, Wolf & Donnelly,<br />

Belgium, 1997. Molluscici<strong>de</strong>s sales represents 10% of all pestici<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

6

Directive 2009/128/EC of The European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a<br />

framework for Community action to achieve the sustainable use of pestici<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

The specific objectives of the Thematic Strategy are:<br />

� to minimise the hazards and risks to health and environment from the use of pestici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

� to improve controls on the use and distribution of pestici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

� to reduce the levels of harmful active substances including through substituting the most<br />

dangerous with safer (including non-chemical) alternatives<br />

� to encourage the use of low-input or pestici<strong>de</strong>-free crop farming, in particular by raising users'<br />

awareness, by promoting co<strong>de</strong>s of good practices and consi<strong>de</strong>ration of the possible application of<br />

financial instruments<br />

� to establish a transparent system for reporting and monitoring the progress ma<strong>de</strong> towards the<br />

achievement of the objectives of the strategy, including the <strong>de</strong>velopment of suitable indicators.<br />

En los últimos años ha aparecido en el mercado un nuevo molusquicida químico, bajo el nombre comercial<br />

<strong>de</strong> Ferramol , fabricado por la empresa alemana Neudorff GMBH. Este producto se presenta también en forma<br />

<strong>de</strong> cebos y contiene fosfato <strong>de</strong> hierro como ingrediente activo. Los ensayos realizados hasta la actualidad para<br />

comprobar su eficacia (Iglesias y Speiser 2001; Speiser y Kistler, 2002) indican que ésta es equiparable a la <strong>de</strong> los<br />

molusquicidas químicos clásicos, metal<strong>de</strong>hído y metiocarbamato. Sin embargo, a diferencia <strong>de</strong> éstos, que son<br />

totalmente sintéticos, el fosfato <strong>de</strong> hierro aparece <strong>de</strong> forma natural formando parte <strong>de</strong> varios minerales,<br />

especialmente la strengita (Fe III PO4 2(H2O) ortorrómbico) y metastrengita (Fe III PO4 2(H2O) monocíclico) (Roberts,<br />

Campbell y Rapp, 1990; Clark, 1993), y es un compuesto con una toxicidad muy baja (EPA, 1998).<br />

La falta <strong>de</strong> medios <strong>de</strong> control <strong>de</strong> plagas <strong>de</strong> gasterópodos cuya utilización esté autorizada en la agricultura<br />

biológica hace que estos animales hayan sido consi<strong>de</strong>rados como los más dañinos para los cultivos biológicos por<br />

numerosas asociaciones profesionales <strong>de</strong> Gran Bretaña y Suiza (Peackock y Norton, 1990; Kesper y Imhof, 1998).<br />

El único agente <strong>de</strong> control biológico que se comercializa en la actualidad para el control <strong>de</strong> plagas <strong>de</strong> babosas es<br />

el nematodo Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita (Schnei<strong>de</strong>r, 1859), lanzado al mercado por primera vez en Gran<br />

Bretaña en 1994. Numerosos ensayos <strong>de</strong> campo realizados en una amplia variedad <strong>de</strong> cultivos y <strong>de</strong> países<br />

europeos han puesto <strong>de</strong> manifiesto que P. hermaphrodita es capaz <strong>de</strong> reducir los daños ocasionados por las<br />

babosas a las plantas (Wilson, Glen y George, 1993; Wilson, Glen, George y Hughes, 1995; Wilson, Hughes y Glen,<br />

1995; Ester & Geelen, 1996; Iglesias, Castillejo & Castro, 2001ab). Su eficacia frente a la especie D. reticulatum<br />

está fuera <strong>de</strong> toda duda (Glen, Wilson, Brain y Stroud, 2000), pero existen indicios <strong>de</strong> que su eficacia contra otras<br />

especies podría ser menor (Wilson et al., 1995a; Coupland, 1995; Glen et al., 1996; Speiser y An<strong>de</strong>rmatt, 1996;<br />

Speiser, Zaller y Neu<strong>de</strong>cker, 2001; Iglesias y Speiser, 2001). La eficacia <strong>de</strong> los tratamientos con P. hermaphrodita<br />

está muy condicionada por la temperatura y la humedad <strong>de</strong>l suelo, que afectan en gran medida a su<br />

supervivencia, pero presenta la ventaja <strong>de</strong> que las condiciones <strong>de</strong> temperatura y <strong>de</strong> humedad que son favorables<br />

para la actividad <strong>de</strong> las babosas lo son también para la supervivencia <strong>de</strong>l nematodo, mientras que los<br />

molusquicidas químicos en forma <strong>de</strong> cebos ven muy mermada su eficacia en las condiciones <strong>de</strong> elevada humedad<br />

en las que los gasterópodos ocasionan la mayoría <strong>de</strong> los daños a las plantas (Glen et al., 1996). No obstante, el<br />

elevado coste económico que suponen en la actualidad los tratamientos <strong>de</strong> control <strong>de</strong> plagas con nematodos<br />

7<br />

The figure examines the<br />

<strong>de</strong>tailed trends within winter<br />

wheat, which accounts for a<br />

45% of the UK cropped area,<br />

and a significant amount of<br />

molluscici<strong>de</strong> use. 2006 report of<br />

indicators reflecting the impacts<br />

of pestici<strong>de</strong> use.

hace que su uso esté todavía muy restringido a cultivos <strong>de</strong> elevado valor como las plantas ornamentales y algunas<br />

hortalizas (Grun<strong>de</strong>r, 2000).<br />

La aplicación <strong>de</strong> molusquicidas representa sólo una medida <strong>de</strong> control a corto plazo, es <strong>de</strong>cir, con ellos se<br />

consigue proteger temporalmente a las plantas <strong>de</strong> los daños que podrían causarle los gasterópodos. Sin embargo,<br />

no tienen un efecto significativo y dura<strong>de</strong>ro sobre las poblaciones <strong>de</strong> gasterópodos resi<strong>de</strong>ntes en las zonas <strong>de</strong><br />

cultivo, por lo que el riesgo <strong>de</strong> que produzcan daños es permanente (Hommay, 2002; Port y Ester, 2002). Ello se<br />

<strong>de</strong>be a que los molusquicidas aplicados afectan sólo a una parte <strong>de</strong> la población, y a que los huevos <strong>de</strong> los<br />

gasterópodos, que se encuentran en el suelo, no se ven afectados por los tratamientos molusquicidas<br />

convencionales, dando lugar a una rápida recuperación <strong>de</strong> las poblaciones (Glen, Wiltshire y Milson, 1988). Se ha<br />

estimado que los tratamientos molusquicidas a base <strong>de</strong> cebos con metal<strong>de</strong>hído o carbamatos matan a menos <strong>de</strong>l<br />

50% <strong>de</strong> la población <strong>de</strong> gasterópodos existente en el momento <strong>de</strong> la aplicación (Glen y Wiltshire, 1986; Wiltshire y<br />

Glen, 1989; Glen, Wiltshire y Butler, 1991). Por otro lado, es frecuente que la cantidad <strong>de</strong> cebo molusquicida<br />

ingerido por los gasterópodos en el campo tenga sólo un efecto subletal transitorio (Kemp y Newell, 1985;<br />

Wedgwood y Bailey, 1986; Briggs y Hen<strong>de</strong>rson, 1987; Bourne, Jones y Bowen, 1988), y se ha comprobado que la<br />

fecundidad <strong>de</strong> los individuos que experimentan ese tipo <strong>de</strong> envenenamiento subletal no se ve afectada, por lo<br />

que continúan poniendo huevos una vez que se recuperan (Kemp y Newell, 1985).<br />

En los años 60 surge el concepto <strong>de</strong>l control integrado <strong>de</strong> plagas (CIP) (Stern, Smith, van <strong>de</strong>r Bosch y<br />

Hagen, 1959), que en la actualidad es parte integrante <strong>de</strong> otro concepto, más amplio, que es el <strong>de</strong>l <strong>de</strong>sarrollo<br />

sostenible. El control integrado <strong>de</strong> plagas implica la integración <strong>de</strong> los conocimientos provenientes <strong>de</strong> multitud <strong>de</strong><br />

campos (biología, química, agronomía, climatología, economía, etc.) con el fin <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>sarrollar las estrategias <strong>de</strong><br />

control más a<strong>de</strong>cuadas <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el punto <strong>de</strong> vista económico, ambiental y <strong>de</strong> salud pública (Dent, 1991). Si bien es<br />

un sistema basado en la combinación <strong>de</strong> diferentes métodos con el fin <strong>de</strong> minimizar el uso <strong>de</strong> pesticidas químicos,<br />

no se <strong>de</strong>scarta, a priori, la utilización <strong>de</strong> ningún tipo <strong>de</strong> agente <strong>de</strong> control (Coombs y Hall, 1998).<br />

Metodológicamente, el control integrado <strong>de</strong> plagas pue<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>scribirse como un "proceso <strong>de</strong> toma <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>de</strong>cisiones" es el que, sobre la base <strong>de</strong> toda la información relevante disponible, hay que <strong>de</strong>cidir qué medidas<br />

tomar y en qué momento aplicarlas, para que el control <strong>de</strong> la plaga resulte, a<strong>de</strong>más <strong>de</strong> eficaz, lo más rentable<br />

posible <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el punto <strong>de</strong> vista económico y lo menos agresivo que sea posible <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el punto <strong>de</strong> vista ambiental<br />

(Bechinski, Mahler y Homan, 2002).<br />

En la actualidad, los programas <strong>de</strong> control integrado <strong>de</strong> numerosas especies <strong>de</strong> artrópodos y <strong>de</strong> hongos<br />

causantes <strong>de</strong> plagas en una gran variedad <strong>de</strong> cultivos, se basan en la utilización <strong>de</strong> sistemas <strong>de</strong> predicción (Dent,<br />

1991; Frahm, Johnen y Volk, 1996). Prever en qué momento una plaga pue<strong>de</strong> producir daños significativos en un<br />

cultivo es fundamental para po<strong>de</strong>r tomar una <strong>de</strong>cisión con respecto a la necesidad <strong>de</strong> aplicar pesticidas para<br />

protegerlo (Buhler, 1996). Por otro lado, <strong>de</strong>pendiendo <strong>de</strong>l modo <strong>de</strong> acción <strong>de</strong>l pesticida, su eficacia pue<strong>de</strong> estar<br />

condicionada por la fase <strong>de</strong>l ciclo en la que se encuentren los organismos causante <strong>de</strong> la plaga o por su nivel <strong>de</strong><br />

actividad (Bailey, 2002). En <strong>de</strong>finitiva, se necesita disponer <strong>de</strong> criterios que permitan <strong>de</strong>terminar tanto la<br />

necesidad y como la conveniencia <strong>de</strong> la aplicación <strong>de</strong> pesticidas.<br />

World Bioci<strong>de</strong>s . Global bioci<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>mand to grow 5.4% annually through 2009 World <strong>de</strong>mand for bioci<strong>de</strong>s<br />

is projected to increase 5.4 percent per year to $6.9 billion in 2009. North America and Western Europe will<br />

remain the largest regional markets, accounting for over two thirds of <strong>de</strong>mand.<br />

The Asia/ Pacific region, due mainly to continued rapid growth in China, is expected to register the fastest growth<br />

among the major regions through this <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>. Eastern Europe is also expected to register above average growth,<br />

but will still account for less than five percent of global <strong>de</strong>mand. In more mature markets, such as Japan, the<br />

United States and Western Europe, advances will be mo<strong>de</strong>st, with gains spurred by the replacement of traditional<br />

products with higher value formulations offering a combination of broad-spectrum efficacy, low toxicity, minimal<br />

effect on finished product quality and reduced environmental impact. Much of this shift will be prompted by the<br />

sizable regulatory framework un<strong>de</strong>r which the bioci<strong>de</strong> industry operates. Many bioci<strong>de</strong>s are synthetic, but a class<br />

of natural bioci<strong>de</strong>s, <strong>de</strong>rived from e.g. bacteria and plants<br />

Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s : an Economic Approach for Pest Management. It is hearting to observe the growing awareness<br />

among the farmers and policy makers about ecologically sustainable methods of pest management. More and<br />

more farmers are coming to realize the short-term benefits and long-term positive effects of the use of bioagents<br />

and other ecologically safe methods to tackle pests. The present article 'Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s' is of much relevance in this<br />

context.<br />

8

'Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s' are certain types of pestici<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong>rived from such natural materials as animals, plants, bacteria, and<br />

certain minerals. Benefits of biopestici<strong>de</strong>s inclu<strong>de</strong> effective control of insects, plant diseases and weeds, as well as<br />

human and environmental safety. Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s also play an important role in providing pest management tools in<br />

areas where pestici<strong>de</strong> resistance, niche markets and environmental concerns limit the use of chemical pestici<strong>de</strong><br />

products.<br />

Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s in general-<br />

(a) have a narrow target range and a very specific mo<strong>de</strong> of action.<br />

(b) are slow acting.<br />

(c) have relatively critical application times.<br />

(d) suppress, rather than eliminate, a pest population.<br />

(e) have limited field persistence and a short shelf life.<br />

(f) are safer to humans and the environment than conventional pestici<strong>de</strong>.<br />

(g) present no residue problems.<br />

Pestici<strong>de</strong> residues in agricultural commodities are being the issue of major concern besi<strong>de</strong>s their harmful effect<br />

upon human life, wild life and other flora and fauna.<br />

Equally worrying thing is about <strong>de</strong>velopment of resistance in pest to pestici<strong>de</strong>s. The only solution of all these is<br />

use of 'Biopestici<strong>de</strong>' that can reduce pestici<strong>de</strong> risks, as-<br />

(a) Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s are best alternatives to conventional pestici<strong>de</strong>s and usually inherently less toxic than<br />

conventional pestici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

(b) Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s generally affect only the target pest and closely related organisms, in contract to broad<br />

spectrum, conventional pestici<strong>de</strong>s that may affect organisms as rent as birds, insects, and mammals<br />

(c) Biopestici<strong>de</strong>s often are effective in very small quantities and often <strong>de</strong>compose quickly, thereby resulting in<br />

lower exposures and largely avoiding the pollution problems caused by conventional pestici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

(d) When used as a fundamental component of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programs, biopestici<strong>de</strong>s can<br />

greatly <strong>de</strong>crease the use of conventional pestici<strong>de</strong>s, while crop yields remain high<br />

(e) Amenable to small-scale, local production in <strong>de</strong>veloping countries and products available in small, niche<br />

markets that are typically unaddressed by large agrochemical companies.<br />

The advances that the proposed project and patents will bring.<br />

To this day, non residual agrochemicals with ovicidal action had not been used to control land snail pests in<br />

agriculture. The strategy proposed in this project is innovative, original and this pest control methods are very<br />

efficient, and makes it very easy to eradicate pest. It is original because it attempts to control the causative agent<br />

pest in the phase of their life cycle [biological cycle] where they are most fragile, in the egg stage. It is an original<br />

method that will <strong>de</strong>velop statistical mo<strong>de</strong>ls to predict the abundance and activity of the land snail with which the<br />

farmer can act in a preventive manner so as not to damage because it will indicate the moment when which has<br />

to apply the ovicidal or the traditional molluscici<strong>de</strong>s. It is original because it doesn´t introduce new pestici<strong>de</strong>s in<br />

agriculture, it is based in non residual agrochemicals that the farmer habitually uses, it seeks the best profile to<br />

exploit its ovicidal activity. It is new because it puts into the hands of the organic farming a number of tools to<br />

control land snails pests using natural fertilizers or <strong>de</strong>terrent strategies implemented by trap plants <strong>de</strong>terring land<br />

snails from attacking crops.<br />

It is a project that uses current technologies to see how the pests live, which are their weaknesses, and attack<br />

them manipulating it that way to minimize si<strong>de</strong> effects on crops, and even on the man. With this project we are<br />

going to obtain results that will be patented. As a result we will be able to patent the pest control strategies,<br />

establish a patent for the active use of non residual agrochemicals with ovicidal action against the land snail´s<br />

egg-lays, and finally be able to patent the Statistical Prediction Activity Mo<strong>de</strong>l and abundance of land snail that<br />

are pests, and most likely be able to patent the use of a zooparasite nemato<strong>de</strong>s for the land snail pests biological<br />

control.<br />

9

1.3 S/T methodology and associated work plan<br />

1.3.1 Overall strategy of the work plan (1 page). Detailed <strong>de</strong>scription of the proposed work<br />

The whole strategy is <strong>de</strong>signed to perform integrated land snail pests control in conventional and organic<br />

farming, and it is here to introduce the use of new molluscici<strong>de</strong>s ovicidal action, capable of <strong>de</strong>stroying the egglays,<br />

the use of trap-plants as a <strong>de</strong>terrent, and the rational use of traditional molluscici<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

WP. 1 .-To un<strong>de</strong>rstand the biology of land snail that are pests in a range of vegetable crops, it is necessary to<br />

have information of the size, structure and dynamics of their populations.<br />

WP. 2 .-To study food and qualitative and quantitative composition of the diet of terrestrial gastropods that<br />

are pests in or<strong>de</strong>r to find plants that can be used as trap plants in organic farming and traditional.<br />

WP. 3 .-To <strong>de</strong>velop a statistical mo<strong>de</strong>l that could explain and predict the abundance and activity of the land<br />

snail as a function of environmental variables such biotic and abiotic.<br />

WP. 4 .-To investigate the feasibility of using plant extracts as biomolluscici<strong>de</strong>s and bio-ovici<strong>de</strong>s. To carry this<br />

out it will also be necessary:<br />

4.1. Laboratory tests on filter paper (direct contact) and artificial soil (standard soil) to select the plant<br />

extracts with molluscicidal and /or ovicidal activity.<br />

4.2. Mini plots experiments on horticultural soil to evaluate the efficacy of the selected plant stract<br />

against lands snails and its eggs.<br />

4.3. Mini plots analysis to know the collateral effect of plant extract selects on invertebrate soil.<br />

4.4. Chemical analysis to find the plant extracts active principle by analytic steps.<br />

WP. 5 .-To investigate the feasibility of using commercial agrochemical activity as ovicidals with control land<br />

snail egg-lays for key Conventionally grown horticultural crops. To carry this out it will also be necessary:<br />

5.1. Laboratory tests on filter paper (direct contact) and artificial soil (standard soil) to select the<br />

agrochemical which best suits the egg types of the pest species and soil type in the study area.<br />

5.2. Field experiments on horticultural crops to evaluate the efficacy of the selected agrochemical as<br />

Ovicidal-molluscici<strong>de</strong>s for the pest control of key conventional grown horticultural crops.<br />

5.3. Field analysis to know the collateral effect of agrochemical selects on invertebrate soil fauna and<br />

bor<strong>de</strong>r effect on wild land snails in conventional horticultural crops.<br />

WP. 6 .- To investigate the feasibility of using swine and cattle manure of killing land snail eggs and plant-tramp<br />

strategy of land snail pest control for key organic horticultural crops grown. To carry this out it will also be<br />

necessary:<br />

6.1. Laboratory testing to <strong>de</strong>termine concentrations of swine and cattle manure that are effective against<br />

the egg-lays of terrestrial gastropods pest. Discriminant trials will be ma<strong>de</strong> on filter paper (direct contact) and<br />

artificial soil.<br />

6.2. Field experiments to evaluate the efficacy of swine and cattle manure land snail egg-lays as control<br />

for key organic horticultural crops.<br />

6.3. Field analysis to investigate the collateral effect of swine and cattle manure on soil invertebrate fauna<br />

and bor<strong>de</strong>r effect on wild land snails in organic horticultural crops.<br />

6.4. Field experiments to use plants as tramp-<strong>de</strong>terrent method to protect organic horticultural crops<br />

WP. 7 .- Make field trials in traditional crops to compare the effectiveness of the control strategy of pest land<br />

snail proposed by us versus conventional approaches of applying chemical molluscici<strong>de</strong>s when observed damage<br />

to the crops. Field experiments in Conventional key horticultural crops to evaluate the efficacy of selected<br />

agrochemical ovicidal with activity against land snail egg-lays in relation to other standard commercial lowchemical<br />

methods of killing animals land snail. Final trial.<br />

WP. 8 .- Field experiments organics in key horticultural crops to evaluate the efficacy of organic Molluscici<strong>de</strong>sovici<strong>de</strong>s<br />

and the use of plant-traps as land snails method to control pests.<br />

WP. 9 .- To i<strong>de</strong>ntify improved strains of nemato<strong>de</strong>s Phasmarhabditis Which are more effective biocontrol<br />

agents of larger land snail species in Hispano-America.<br />

10

METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH WORK PACKAGES<br />

<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Package</strong> 1<br />

Field research to investigate life cycle of land snail past in horticultural crops<br />

Partners 1 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 2 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 3 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 4 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 5 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 6 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 7 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 8 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 9 (……. Man-month)<br />

OBJETIVES<br />

To investigate size, structure and dynamic of land snail for a key horticultural crops<br />

Estudiar el tamaño, estructura y dinámica <strong>de</strong> sus poblaciones.<br />

BACKGROUND<br />

Methodological review. Many methods have been used to make quantitative studies of land snail populations.<br />

According to South (1992) these methods can be qualified in three categories:<br />

A. Absolute methods, expresses the number of individuals per unit area.<br />

B. Relative methods, expresses the number of individuals per unit effort or the relation to non-standardized traps.<br />

C. Indirect methods, expresses sizes of population in terms of traces left or the effects produced by land snails<br />

(for example, <strong>de</strong>pending on the damage extension done to the crop, or according to bait consumption).<br />

Relative methods are faster and much more comfortable but they have the disadvantage that the estimates are<br />

highly <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nt of the land snail activity levels, this can lead to incorrect population sizes because of weather<br />

conditions that have an important effect on the land snail activity (Getz, 1959; Hunter, 1968a; South, 1992).<br />

Absolute Methods involve the absolute quantification of individuals per surface area. This can be done on site by<br />

applying an irritant substance to a <strong>de</strong>termined area. For years formal<strong>de</strong>hy<strong>de</strong> was used for this purpose, but South<br />

(1964) rejected this method when he realized that most of the land snails died before they could reach the<br />

surface. Högger (1993) proposed a new method. First he <strong>de</strong>termines an area, limiting it with a metal ring of 15 cm<br />

of height; then he introduces it in to the ground to a <strong>de</strong>pth of 5 cm. Once done this, he applies mustard oil to the<br />

ground and captures the land snails that come out to the surface. Another method, proposed by Ferguson,<br />

Barratt & Jones (1989), it is based on the placement of shelter traps located insi<strong>de</strong> of the area <strong>de</strong>termined by the<br />

metal ring, which in this occasion is covered with a top that prevents the escape of land snails and helps to keep<br />

the humidity (moisture) insi<strong>de</strong>. The shelter traps and the area insi<strong>de</strong> the ring are inspected each day removing the<br />

land snails caught, until no new individuals appear.<br />

Another way of obtaining absolute estimates is to take soil samples of known surfaces and transfer them to the<br />

laboratory for further land snail extraction and quantification. The extraction can be done by; the progressive<br />

flooding of the soil samples to make land snails surface, or by washing the soil sample on sieves with water. South<br />

(1964) compared the last sieving method with absolute methods (flooding with cold or hot water, extraction with<br />

chemicals, dry sieving) and relative methods (trapping, Direct observation during night). South conclu<strong>de</strong>d that the<br />

water sieving is the most reliable method, since it allows the recovery of almost the 100% of the land snails<br />

contained in one soil samples. Hunter (1968a) proved the efficiency of this method when he recovered almost all<br />

individuals of a known population; South (1964) conclu<strong>de</strong>s that the water sieving is the most accurate method;<br />

It´s also is the only reliable method to obtain and quantify land snail lays.<br />

Almost all the authors agree that land snails and it´s lays are located in the uppermost stratum of the soil.<br />

According to South (1964), 100% of the lays and land snails of D. reticulatum species is located in the first 2 or<br />

11

3cm of soil in field areas. In crop areas, Hunter (1966) found out that 83% of individuals of D. reticulatum were<br />

located in the soil first 7´5cm, and a 6% were located above 15cm. Also in crop areas, Runham & Hunter (1970)<br />

observed that in the first 10cm of soil contained the 97% of D. reticulatum. Rollo & Ellis (1974) pointed out that<br />

the 90% of snail lays are also located in the same soil layers. According to Marquet (1985), in standard conditions<br />

any land snail appears above the first 5cm of soil, However in exceptionally severe winters up to a 15% of<br />

individuals may appear at <strong>de</strong>pths between 10 and 20cm. South (1992) suggests that sampling the soil´s first 10cm<br />

it´s enough to quantify land snail populations.<br />

Importancia: el WP. 1 es importante ya que nos va a proporcionar información sobre el tamaño,<br />

estructura y dinámica <strong>de</strong> la población <strong>de</strong> caracoles y babosas plaga, información que emplearemos en el<br />

<strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong>l mo<strong>de</strong>lo predictivo<br />

Assessment of progress and results. Por medio <strong>de</strong> los informes semestrales y anuales, y por medio <strong>de</strong> los<br />

controles personales que periódicamente el coordinador realiza a cada uno <strong>de</strong> los partner en el país<br />

correspondiente.<br />

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------<br />

Task 1.1<br />

Objetives<br />

Studying the land snail population size in crops where they will conduct the study.<br />

Participants: all partners<br />

Materials and Methods<br />

The methodology used is based on absolute estimation methods; land snails quantification of known surface soil<br />

samples.<br />

Soil sampling.<br />

The choice of the sampling location is randomly selected. To carry this out the plot is divi<strong>de</strong>d in a grid composed<br />

at least of 50 frames of 4 x 4 m; each one subdivi<strong>de</strong>d in four quadrants. The quadrants are <strong>de</strong>termined using the<br />

last two digits of the randomly generated value of the “random” (ran) calculator function. Once selected 20<br />

frames, we proceed to <strong>de</strong>termine which quadrant of each frame, by using again the calculator random number<br />

generator following the next co<strong>de</strong>: 0,000-0,249 for the upper left quadrant; 0,250-0,499 for the upper right<br />

quadrant; 0,500-0,749 for the lower left quadrant; 0,750-0,999 for the lower right quadrant.<br />

The sample extraction is performed with a rectangular spa<strong>de</strong> mark with the <strong>de</strong>pth to be achieved (10<br />

centimeters). First is selected the area to take the soil sample, then we place on the ground an aluminum frame<br />

of 25 x 25 cm, then the spa<strong>de</strong> is stuck in to the ground along its entire contour until the marked <strong>de</strong>pth and extract<br />

the sample. Each sample is introduced in a properly labeled opaque plastic bag; these bags are conserved in a<br />

cold storage at 4ºC in the dark, for its further laboratory analysis in the next 3 days.<br />

To <strong>de</strong>termine the number of soil samples nee<strong>de</strong>d its used an statistical software; The means and variances of the<br />

average land snails and eggs are calculated, to find out all the possible combinations of 2 samples, 3samples,<br />

4samples till the total of 20 samples. For each number of samples the <strong>de</strong>gree of error is calculated dividing the<br />

standard <strong>de</strong>viation by the arithmetic mean. In previous investigations we observed that to obtain a <strong>de</strong>gree of<br />

error less or equal to 10%, 18 samples are enough in the case of land snails and 16 in the case of eggs.<br />

The abundance of land snails and eggs is estimated by washing the soil samples prece<strong>de</strong>nt from the study plots.<br />

On a monthly basis 20 soil samples of 25x25 cm square and 10 cm <strong>de</strong>ep.<br />

Soil samples treatment. Each sample is placed individually on a white plastic tray; in the first place the sample is<br />

thoroughly inspected to capture any snail that might be in the soil surface, once done this the vegetal cover is<br />

removed, cutting it with scissors; then the soil sample is washed in sieves, with a <strong>de</strong>creasing mesh sizes from<br />

4mm to 1mm. The soil samples are crumbled to smaller pieces with the help of the water jet. The thicker roots<br />

are cut to smaller pieces. The sieves content is carefully inspected un<strong>de</strong>r a 10X magnifying glass and a powerful<br />

white light source.<br />

12

Larger land snails are retained in the upper sieve, and in the lower sieve the smaller land snails and the eggs. The<br />

collected land snails are kept in a tray and the eggs in a Petri dish, both with a humid filter paper. Once finished<br />

separating eggs and land snails from the soil samples we proceed to i<strong>de</strong>ntify them.<br />

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------<br />

Task 1.2<br />

Objetives<br />

Field experiments to investigate<br />

To know the land snails pests populations dynamic and structure.<br />

Participant: All partners<br />

Materials and Methods<br />

To study the population structures and variation over time it´s necessary to <strong>de</strong>termine the maturity state<br />

of the land snails constituting the population along time. Because of this, Bett (1960), Hunter (1968a), and Hunter<br />

& Symonds (1971), based their studies exclusively on sperms presence or absence along the genital tract. South<br />

(1989a) used the same methodology, but he also obtained the gonad and albumin gland mass, (Hermaphrodite<br />

Gland In<strong>de</strong>x, H.G.I. and Albumin Gland In<strong>de</strong>x A.G.I. respectively, of each individual. This in<strong>de</strong>x express the % of<br />

corporal mass represented by each gland, that have a characteristically variation along the maturation cycle of D.<br />

reticulatum.<br />

Duval & Banville (1989) and Barker (1991), in adition to calculating the H.G.I. and A.G.I., incorporated in<br />

their work the gonad cytological analysis of individuals, and <strong>de</strong>termined their maturity level using as reference the<br />

previous studies of Runham & Laryea (1968), based on the presence and relative abundance of each cellular type<br />

in gonad gametogenisis in D. reticulatum gonad. Haynes et al. (1996) classified the land snails in five categories<br />

based on the body mass in<strong>de</strong>x H.G.I. A.G.I. instead of using the cytological gonad analysis to <strong>de</strong>scribe the<br />

population structure. The population dynamic and structure study are only done on the species that really are a<br />

pest; in our previous studies (Barrada, 2003) we focused exclusively on Deroceras reticulatum that really<br />

constitute a pest in the European crops.<br />

Individual management. Individuals belonging to the pest species are weight on a laboratory balance to the<br />

hundredth of milligram, and then they are sacrificed by a brief immersion in water at 50ºC. This method is a<br />

modification from the Haynes, Rushton y Port (1996) method, which is to dip them in boiling water. The sacrificed<br />

individuals are introduced in properly labeled glass tubes, with preservation 70% alcohol. Then the individuals are<br />

dissected and they have their hermaphrodite gland and albumin gland removed, which is used to <strong>de</strong>termine the<br />

maturity state of individuals.<br />

Following Barker (1991) approach, individuals with BMI(body mass in<strong>de</strong>x) exceeding 20 mg are not dissected,<br />

assuming that they don´t have a differentiated gonad. The hermaphrodite and albumin gland, extracted from<br />

individuals with BMI greater or equal to 20 mg, the glands are weighed up to the hundredth of milligram<br />

immediately after its extraction. The hermaphrodite gland is fixed with Carnoy for 24 hours and preserved in<br />

alcohol 70%.<br />

Determining the maturity <strong>de</strong>gree. It will follow the methodology used by Duval & Banville (1989) and Barker<br />

(1991), the sexual maturity status of individuals at each monthly sampling is <strong>de</strong>termined by gonad cytological<br />

analysis, using as a reference the states <strong>de</strong>fined by Runham & Laryea (1968) . To this end, each individual gonad<br />

was <strong>de</strong>hydrated by a series of ethanol baths of progressively higher <strong>de</strong>gree (70%, 96% and 100%), ending with 2<br />

baths of toluene. Next the sample is inclu<strong>de</strong>d in a paraffin block; which is sectioned at 8 μ thick. Obtained sections<br />

are rehydrated by reversing the previous <strong>de</strong>hydration, replacing toluene by xylene and dipping them in distilled<br />

water. Then the sections are stained using hematoxylin-eosin staining, and finally <strong>de</strong>hydratated again.<br />

Each cellular type that appear in the selected land snails gonad and the maturity states are available in Pelluet &<br />

Watts (1951), Watts (1952), Bridgeford & Pelluet<br />

(1952), Hen<strong>de</strong>rson & Pelluet (1960), Smith (1966), Runham & Laryea, (1968), Bailey (1973), Hill & Bowen (1976),<br />

Parivar (1978, 1980, 1981), Nicholas (1984), South (1992), Fawcett (1987) and Lutchel et al. (1997) works.<br />

13

Each captured individual was i<strong>de</strong>ntified as belonging to one of the following sexual maturity stages: i)<br />

undifferenciated spermatogonia, ii) spermatocyte, iii) spermatid, iv) espermatozoa, v) oocyte and vi) senescent.<br />

The first three states correspond to immature land snails, with no reproduction ability; sexually mature land snails<br />

are those that are in spermatozoon and oocyte state (Runham y Laryea, 1968; South 1989a).<br />

In other words, each captured individual is characterized by their body mass (mg), by their maturity state<br />

and by the mass (mg) of the hermaphrodite and albumin gland. From these values it´s calculated for each<br />

individual, the hermaphrodite gland in<strong>de</strong>x (H.G.I.) and the albumin gland in<strong>de</strong>x (A.G.I.), as follows,<br />

H.G.I. = Hermaphrodite gland mass 100 / individual mass<br />

A.G.I. = Albumin gland mass 100 / individual mass<br />

For each sample occasion, individuals who have similar characteristics referring to its sexual maturity<br />

state and body mass in<strong>de</strong>x values, H.G.I. and A.G.I., are consi<strong>de</strong>red as belonging to the same land snail<br />

generation.<br />

In this research project we follow the methodology used by Duval & Banville (1989) and Barker (1991) for<br />

the population structure study. As these authors did, we assume that individuals with body mass exceeding 20mg<br />

are land snails with completely undifferentiated gonads (from the cytological viewpoint) are not analyzed. In this<br />

regard, it should be mentioned that South (1989a) indicates a value of 40 mg body mass as a limit from which, the<br />

maturity state of D. reticulatum can be <strong>de</strong>fined by studying the cytology of the testis. Previous obtained results<br />

agree with the values set by South (1989a).<br />

14

<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Package</strong> 2<br />

Field research to investigate the feeding habits and the qualitative and quantitative diet of land snails in<br />

horticultural crops.<br />

Objetives<br />

To Study land snail feeding and qualitative and quantitative composition of their diet in or<strong>de</strong>r to find plant<br />

species that can be used as trap plants in organic farming.<br />

Partners 1 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 2 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 3 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 4 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 5 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 6 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 7 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 8 (……. Man-month)<br />

Partners 9 (……. Man-month)<br />

Background<br />

El estudio <strong>de</strong>l material ya ingerido por los caracoles y babosas se realiza mediante el análisis microscópico<br />

<strong>de</strong> los pequeños fragmentos <strong>de</strong> plantas que se encuentran en las heces o en el interior <strong>de</strong>l tubo digestivo <strong>de</strong> los<br />

animales. Este método ha sido utilizada por Grime, Blythe y Thornton (1970), Mason (1970), Wolda et al. (1971),<br />

Chatfield (1975), Richardson (1975), Williamson y Cameron (1976), Szlavecz (1986), Speiser y Rowell-Rahier<br />

(1991), Hatziioannou et al. (1994), para estudiar la dieta <strong>de</strong> caracoles como Cepaea nemoralis, Oxychilus cellarius<br />

(Müller, 1774), Oxychilus alliarius (Miller, 1822), Discus rotundatus (Müller 1774), Arianta arbustorum (Linneo,<br />

1758), Mona<strong>de</strong>nia hillebrandi (Smith, 1957), Monacha cantiana (Montagu, 1803), Monacha cartusiana (Müller,<br />

1774), Braybaena fructicum (Müller, 1774), Helix lucorum (Linneo, 1758), Xeropicta arenosa (Ziegler, 1827) y<br />

Cepaea vindobonensis (Férussac, 1821). Hunter (1968b), Pallant (1969, 1972), y Jennings y Barkham (1975) la han<br />

utilizado para estudiar la dieta <strong>de</strong> babosas como Deroceras reticulatum, Tandonia budapestensis (Hazay, 1881),<br />

Arion hortensis Férussac, 1819, y Arion ater.<br />

El estudio <strong>de</strong> las heces es un método más rápido que el análisis <strong>de</strong>l contenido estomacal, ya que no<br />

requiere el sacrificio y disección <strong>de</strong> los animales. Sin embargo, los materiales presentes en las heces han<br />

atravesado todo el tubo digestivo <strong>de</strong>l animal y se encuentran más <strong>de</strong>gradados, por lo que resultan más difíciles <strong>de</strong><br />

i<strong>de</strong>ntificar que los extraídos <strong>de</strong>l estómago (Cook y Radford, 1988; Hatziioannou et al., 1994). El estudio <strong>de</strong> heces<br />

es un método a<strong>de</strong>cuado para <strong>de</strong>terminar la presencia o ausencia <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>terminados elementos en la dieta <strong>de</strong> los<br />

animales, pero la proporción <strong>de</strong> materiales no i<strong>de</strong>ntificados en las heces suele ser tan elevada, que no resulta un<br />

método útil para realizar una caracterización cuantitativa <strong>de</strong> la alimentación (Williamson y Cameron, 1976;<br />

Szlavecz, 1986; Speiser y Rowell-Rahier 1991). Vadas (1977) indica que los materiales más abundantes y más<br />

fácilmente i<strong>de</strong>ntificables en las heces <strong>de</strong> los animales son los menos utilizados metabólicamente y que,<br />

posiblemente, son también los ingeridos en menor cantidad, por lo que el análisis <strong>de</strong> heces conduce a una<br />

sobrevaloración <strong>de</strong> los alimentos poco consumidos; por el contrario, los alimentos más consumidos son<br />

infravalorados <strong>de</strong>bido a que son digeridos en mayor medida y resultan más escasos y difíciles <strong>de</strong> i<strong>de</strong>ntificar en las<br />

heces.<br />

El análisis <strong>de</strong>l contenido <strong>de</strong>l tubo digestivo <strong>de</strong> los animales es un método más laborioso, pero proporciona<br />

una imagen más real <strong>de</strong> la dieta <strong>de</strong> los animales (Norbury y Sanson, 1992). Pallant (1969, 1972) estudió la<br />

alimentación <strong>de</strong> D. reticulatum en poblaciones naturales (bosques y pra<strong>de</strong>ras) mediante el análisis <strong>de</strong> contenidos<br />

estomacales. Para reducir al máximo la <strong>de</strong>gradación digestiva <strong>de</strong>l alimento ingerido por los caracoles y babosas<br />

capturadas y facilitar su i<strong>de</strong>ntificación, Pallant (1969, 1972) introdujo directamente a los animales capturados en<br />

alcohol al 70%, y realizó su disección para la extracción <strong>de</strong>l contenido <strong>de</strong>l tubo digestivo a lo largo <strong>de</strong> las 2 horas<br />

siguientes a la captura. Triebskorn y Florschutz (1993) realizaron un estudio sobre el tránsito <strong>de</strong>l alimento a través<br />

<strong>de</strong>l tubo digestivo <strong>de</strong> D. reticulatum, mediante la utilización <strong>de</strong> un preparado alimenticio (lechuga, maíz y leche en<br />

polvo) marcado radiactivamente y la toma <strong>de</strong> radiografías <strong>de</strong> los animales a intervalos regulares; según sus<br />

resultados, el alimento ingerido penetra inmediatamente en el buche, estómago y parte anterior <strong>de</strong>l intestino,<br />

lugares en los que permanece durante un período mínimo <strong>de</strong> dos horas y media antes <strong>de</strong> comenzar a avanzar por<br />

15

el intestino; el buche y el estómago se vacían completamente en el curso <strong>de</strong> las trece horas siguientes a la<br />

ingestión.<br />

Importancia: la información que se obtenga <strong>de</strong> este estudio nos servirá para diseñar las estrategia <strong>de</strong>l uso<br />

<strong>de</strong> plantas-trampas como agentes disuasorios y conocer y evaluar los daños reales sobre los cultivos.<br />

Assessment of progress and results. Por medio <strong>de</strong> los informes semestrales y anuales, y por medio <strong>de</strong> los<br />

controles personales que periódicamente el coordinador realiza a cada uno <strong>de</strong> los partner en el país<br />

correspondiente.<br />

<strong>Work</strong> and methodology Description<br />