Dimension

Taking you beyond the small screen, Dimension is an entertainment magazine for people who want to think critically about their TV.

Taking you beyond the small screen, Dimension is an entertainment magazine for people who want to think critically about their TV.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

A NEW CURVED<br />

SENSATIONAL<br />

DISCOVERY<br />

For thousands of years, people laughed at the idea of the earth as round. Until one<br />

man stepped forward, gave us new perspectives, and changed the world forever.<br />

Now it’s time to change perspectives again. Our new, curved LG OLED-TV will give<br />

you a greater sense of realism and depth. A new perspective on TV as we know it.<br />

When it’s all possible, life’s good.

Front Cover Ad Part 2

Contents<br />

Fall 2016<br />

20<br />

No, The TV Business<br />

Isn’t Dead Yet 10<br />

Julia Greenberg<br />

Meet Symphony,<br />

The Company that<br />

tracks Netflix’s<br />

elusive Ratings<br />

K.M. McFarland<br />

13<br />

14<br />

HELLO,<br />

FRIEND<br />

Jen Hedler Phillis<br />

Sense8 and the Failure of the<br />

Global Imagination<br />

Claire Light<br />

28<br />

Modern<br />

Marvel<br />

Jason Tanz<br />

34<br />

42<br />

42 Reviews<br />

Blackish, cleverman, &<br />

transparent<br />

48<br />

TV’s More Inclusive,<br />

But It Has a Long<br />

Way to Go<br />

Jason Parham<br />

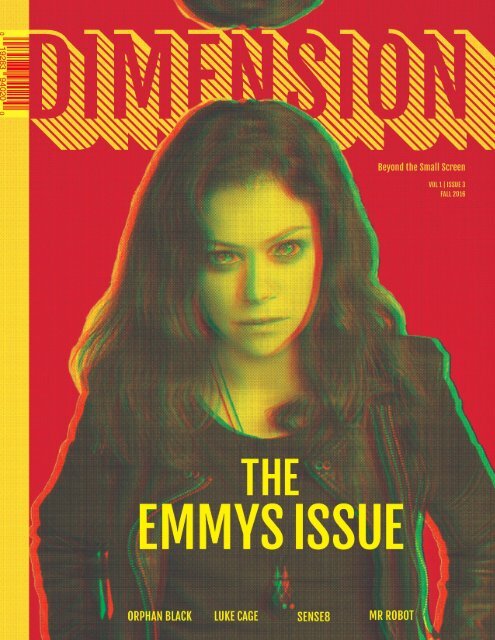

Issue<br />

V.1<br />

the<br />

emmys<br />

issue<br />

Cover: Tatiana Maslany<br />

Photography: BBCAmerica<br />

What Orphan Black<br />

Can Teach Us<br />

Alenka Figa<br />

DIMENSION 3

3:47 PM<br />

Nearly 10,000 reported<br />

killed by China quake<br />

2:37 PM - 12 May 2008<br />

dtan<br />

@dtan<br />

Following<br />

EARTH QUAKE in Beijing?? Yup... @kese<br />

I felt it too!!<br />

The 2008 China Earthquake. First On

5:55 PM<br />

An earthquake struck China today with<br />

early reports that 7,600 people died in<br />

Sichuan province alone<br />

8:55 PM<br />

Thousands dead in Chinese quake

Letter<br />

from the<br />

Editor<br />

Award shows don’t always keep pace with the television<br />

industry — many, if not most these days it seems, receive<br />

well-deserved criticism for falling out of touch with audiences<br />

and creators alike. At <strong>Dimension</strong>, we rarely feel<br />

the need to add to the wealth of related media coverage.<br />

Our mission is not to keep up with the latest news, but<br />

to publish journalism that pushes us to think critically<br />

about the narratives the television industry is putting<br />

out in the world.<br />

However, this year’s Emmy Award winners reflect<br />

a long-overdue (and far from complete) shift toward<br />

diversity in the television industry. Rami Malek, Tatiana<br />

Maslany, Aziz Ansari, Alan Yang, Sarah Paulson, Sterling<br />

K. Brown, and Courtney B. Vance were all handed Emmys<br />

this season, and two of the white men who picked up<br />

awards — Louie Anderson and Jeffrey Tambor — won<br />

for their sensitive and thoughtful portrayals of female<br />

characters. But Tambor’s acceptance speech set a tone not<br />

of self-congratulation, but of necessary forward momentum,<br />

in his passionate and self-sacrificing plea for trans<br />

actors to play trans characters, “I would not be unhappy<br />

if I was the last cisgender male to play a trans female on<br />

television. We have work to do.”<br />

Here at <strong>Dimension</strong>, we believe that work is important.<br />

The stories we tell change the way we think about the<br />

world we live in, and who we choose to tell those stories<br />

is as important as what stories get told. As the television<br />

industry pushes to portray a more complete and meaningful<br />

picture of modern cultures, it’s important to step back<br />

and reflect on both its successes and its failures.<br />

The Emmys reminded us of the breadth of narratives<br />

at our fingertips this year. This issue of <strong>Dimension</strong> takes<br />

a closer look at what the shows we’re celebrating have<br />

to say, how they’re saying it, and what that says about us.<br />

Photography: Alex Hewitt<br />

Editor<br />

Copyeditor<br />

Contributors<br />

Graphic Designer<br />

Photographer<br />

Creative Director<br />

Published by<br />

Jenni Sands<br />

Kassy Rodeheaver<br />

Alenka Figa<br />

Julia Greenberg<br />

Delia Harrington<br />

Claire Light<br />

K.M. McFarland<br />

Jason Parham<br />

David Pierce<br />

Jen Hedler Phillis<br />

Jason Tanz<br />

Jenni Sands<br />

Alex Hewitt<br />

Jill Vartenigian<br />

Seattle Central<br />

1701 Broadway<br />

Seattle, WA<br />

dimensionmagazine.com<br />

<strong>Dimension</strong> Magazine is a Seattle Central College Printing<br />

publication issued 4 times a year. Reproduction in whole<br />

or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited.<br />

All manuscripts, photos, video, drawings, and other<br />

materials submitted must be accompanied by a stamped<br />

self-addressed envelope. <strong>Dimension</strong> Magazine cannot<br />

be held responsible for any unsolicited materials. Subscriptions<br />

are available for $35.00 per year for US addresses<br />

and $50.00 per year for Canadian addresses.<br />

Single price is $11.99. Contents are copyright © 2016 by<br />

Jenni Sands, except for all articles and photography,<br />

which are used for educational purposes only.<br />

Jenni Sands<br />

Founder & Editor<br />

6 DIMENSION

Nope,<br />

the TV Business Isn’t Dead Yet.<br />

Far From It, Really.<br />

Over the past few years, media<br />

analysts have bemoaned the End<br />

of TV. Some have wondered, as<br />

ratings tumble year after year,<br />

why would advertisers continue<br />

to buy ads? Meanwhile Facebook<br />

and Google’s ad businesses have<br />

exploded, even though marketers<br />

aren’t spending drastically more<br />

than they have in the past. But<br />

the traditional TV industry is not<br />

dead just yet.<br />

This fall, CBS, 21st Century Fox, and Time Warner<br />

all reported advertising revenue growth. CNN and<br />

Fox acknowledged they’ve seen higher ratings (and<br />

ad revenue) thanks in part to the election. And,<br />

sure, CBS had the Super Bowl this year. Even so,<br />

the company says its ad revenue is “the strongest<br />

we’ve seen in a long, long time.”<br />

The media business runs on ads. But since the<br />

birth of the web, the ad business has been changing.<br />

Analysts expect brands to spend $68.8 billion<br />

dollars this year on digital advertising, according<br />

to eMarketer. Even so, TV has remained the single<br />

biggest recipient of marketers’ money. As more<br />

people abandon traditional TV for streaming services,<br />

YouTube, and social media, broadcasters will<br />

have to fight to keep advertisers coming back. But<br />

by then, the dichotomy between TV and digital<br />

may not mean much anyway.<br />

“It’s definitely a complicated picture,” says senior<br />

analyst Paul Verna of eMarketer. “But it’s not easy<br />

to say digital is killing TV.”<br />

Protecting the Business<br />

In its own way, TV is still pretty unique. The internet<br />

dramatically changed the newspaper, magazine, and<br />

radio industries. Many advertisers are no longer<br />

willing to pay top prices (or advertise at all) in those<br />

places as the audience shifted online.<br />

8 DIMENSION

“<br />

“There’s a lot more inertia in television than there was<br />

in the media that succumbed more quickly to disruption<br />

from the Internet,” says Andrew Frank, a longtime analyst<br />

at Gartner who follows the marketing industry.<br />

How have major broadcasters and cable networks held<br />

onto their dominant share of the public’s attention? Well,<br />

for one, people still watch a lot of TV on TV. Major sporting<br />

events, like the Super Bowl and the Olympics, draw<br />

millions of viewers. And yes, electoral politics still largely<br />

play out on television. “TV still has massive scale, it has<br />

that cachet,” Verna says. “If it’s on TV, it’s important.”<br />

And advertisers want to be where they can reach people.<br />

Even for those who don’t watch TV in the old-fashioned<br />

way, many networks have developed their own websites,<br />

It’s definitely a complicated<br />

picture, but it’s not easy to say<br />

digital is killing TV.<br />

”<br />

apps, and digital services. Advertisers consider ads on<br />

websites and apps “digital spend.” For networks, however,<br />

it’s all ad money coming their way.<br />

Take Fox. Advertisers can buy slots during The Simpsons<br />

on its broadcast station or The Americans on basic cable.<br />

They can serve ads during full episodes streaming on its<br />

website, streaming apps, and Hulu. (During last week’s<br />

earnings call, 21st Century Fox’s CEO James Murdoch<br />

called the going rate for ads for Fox’s shows on Hulu “very,<br />

very attractive.” Fox owns Hulu in a joint partnership with<br />

Disney–ABC and NBC Universal.)<br />

But when advertisers are spending money for ads attached<br />

to TV streaming on the internet, they don’t think of it as TV.<br />

“Hulu, Roku, Apple TV. Is that television? No, it’s not.<br />

It’s consumed on a big screen potentially in your living<br />

room, but we consider anything delivered by an IP device is<br />

not linear TV,” says David Cohen, the president of Magna<br />

US TV vs. Digital Ad Spending<br />

in billions of dollars<br />

Global in North America, a major ad-buyer that works<br />

with companies like Coca Cola and Johnson & Johnson.<br />

In other words, networks are getting advertisers’ money<br />

both ways, which for the moment seems to have led to an<br />

overall bump. But Cohen predicts marketers will begin<br />

to see more of the distinction blur. “In the short term, I<br />

think it’s not outlandish to think that a billion dollars<br />

will come out of the linear television market this year and<br />

move to digital video.”<br />

Time of Transition<br />

And yet that doesn’t mean that the future for broadcasters<br />

and cable networks is ultimately secure. Analysts with<br />

eMarketer estimate that more money will be spent on<br />

digital advertising than TV by next year. Ad buyers and<br />

marketers are frustrated with the fact that TV ads continue<br />

to increase in cost even as ratings, for the most part,<br />

continue to fall. “Why as marketers have we agreed to pay<br />

more for that decline in audience is exactly the question,”<br />

Cohen says. Magna, for its part, said last week that it<br />

was moving $250 million from its TV budget to YouTube.<br />

As the basic cable bundle comes apart and viewers<br />

get more options to pay for fewer channels in so-called<br />

“skinny bundles,” Frank believes that less popular channels<br />

may struggle as advertisers shift dollars to digital<br />

content people actually watch. But digital advertising is<br />

also complicated. Facebook and Google may dominate<br />

when it comes to competing in the digital space. But the<br />

ads still have to be shown to be effective, which is easier to<br />

demonstrate through “apples-to-apples” comparison. This<br />

is why YouTube, with its TV-like pre-roll ads, has thrived.<br />

Over time, ad tech will get better at helping marketers<br />

understand who you are, where you’re watching, and<br />

what you want, whether you’re on Facebook, YouTube,<br />

or just watching plain old TV. And that may help save<br />

traditional TV simply because advertisers will be able to<br />

show couch potatoes more ads for stuff they really do want.<br />

Television may be changing. But evolution is, if nothing<br />

else, a survival strategy.<br />

$71.29<br />

$72.09<br />

$72.72<br />

$82.86<br />

$74.53<br />

$93.18<br />

$76.02<br />

$103.39<br />

$77.93<br />

$113.18<br />

2016<br />

2017<br />

2018<br />

2019<br />

2020<br />

Source: eMarketer, Sept 2016<br />

9

Meet Symphony<br />

the Company That Tracks Netflix’s Elusive Ratings<br />

By K.M. MacFarland<br />

During an otherwise routine panel at the Television Critics<br />

Association Winter press tour, NBC research president<br />

Alan Wurtzel dropped a bombshell: He knew — or at least<br />

had an idea — how many people were watching Netflix’s<br />

original series. It was a sit-up-and-pay-attention moment.<br />

The head of research for a broadcast network was pulling<br />

back the curtain on viewership numbers that had long<br />

eluded TV reporters everywhere.<br />

It’s no secret that television networks have long wanted<br />

alternatives to the traditional Nielsen ratings. What<br />

Wurtzel revealed was that NBC had found one — Palo<br />

Alto-based Symphony Advanced Media, which had viewership<br />

numbers for Netflix and others. It drew the data<br />

from tech that was still “in beta,” Wurtzel said, but it<br />

nonetheless showed Jessica Jones averaging 4.8 million<br />

viewers aged 18–49 while Master of None had 3.9 million<br />

adults in the same group.<br />

Until now, no one has been able to approximate the<br />

audience for shows available exclusively on streaming<br />

Instead of the set-top box<br />

that Nielsen families use,<br />

Symphony created an app<br />

that tracks what users are<br />

watching in much the same<br />

way Shazam identifies a<br />

song playing at a party.<br />

services. Netflix’s numbers — other than subscriber figures<br />

it reports each quarter — are shrouded in secrecy, even for<br />

show creators. As it stands, Netflix will share data on its<br />

successes — noting that Beasts of No Nation was viewed 3<br />

million times in its first two weeks of release, for example,<br />

or that The Ridiculous 6 is the most-watched film in Netflix<br />

history — but not much beyond that. Symphony — which<br />

touts Charlie Buchwalter, who spent 13 years at Nielsen, as<br />

its president and CEO — helps put an unofficial number<br />

on streaming viewership.<br />

Collecting Data, Shazam–Style<br />

Symphony launched its VideoPulse service in September,<br />

with NBC, Viacom, Warner Bros., and A&E as beta testers.<br />

Buchwalter says the system was designed to catch the<br />

“30–35 percent of viewership actually happening beyond”<br />

the live-plus-seven rating (L+7) that tracks a program’s<br />

viewership during the seven days after it airs and is the<br />

standard used to determine advertising fees. VideoPulse<br />

then tracks the mobile streaming habits of users, who<br />

are paid $5–$13 based on how many devices they set up,<br />

to calculate viewership.<br />

VideoPulse’s sophisticated audio recognition technology<br />

lets the software run passively on a mobile device,<br />

identifying a television program through its microphone<br />

to log viewing habits. Instead of the set-top box that<br />

Nielsen families use, Symphony created an app that tracks<br />

what users are watching in much the same way Shazam<br />

identifies a song playing at a party.<br />

“We have a partner that has access to all 210 national<br />

channels in the US,” says Buchwalter, “and every piece<br />

of content that comes over those channels has an audio<br />

fingerprint included in them, which has to do with a<br />

particular episode of a particular program on a particular<br />

network.” When the service launched, it tracked all<br />

broadcast and cable programs. But throughout October<br />

DIMENSION 11

and November, Symphony added tracking for high-profile,<br />

critically-acclaimed streaming service shows like Orange<br />

Is the New Black, Transparent, and Master of None.<br />

For streaming shows, Symphony’s app tracks the number<br />

of people who watch any episode of a particular series over<br />

a 35-day period, then averages that total to determine a<br />

per-episode rating. For example, Narcos averaged 3.2 million<br />

viewers aged 18-49. Amazon’s Man in the High Castle,<br />

which has been identified as the highest-rated Amazon<br />

Prime original, averaged 2.1 million viewers.<br />

Symphony is one of a few companies attempting to fill<br />

the perceived gaps in how Nielsen collects viewer data.<br />

And right now it’s going about it by forming a diversified<br />

user base from which larger demographic information<br />

can be extrapolated. “We have our own panel of around<br />

15,000 mobile device users,” says Buchwalter, who also<br />

notes that Symphony’s app works with cell phone and<br />

Wi-Fi networks, as well as a GPS component to note<br />

where users are accessing media, whether it’s “at home,<br />

in the car, or in the parking lot of a Target.”<br />

Looking Inside the Black Box<br />

Frustration with Netflix’s secrecy about viewership numbers<br />

runs deep among TV executives, and Wurtzel, however<br />

obliquely, smashed the streaming service’s black box viewership<br />

with his TCA presentation. To be fair, television<br />

executives have long complained that Nielsen ratings<br />

aren’t accurate and Symphony’s numbers are still in beta<br />

testing, but given how long everyone’s been wondering<br />

many people are watching Netflix and Amazon original<br />

series, any data at all is eye-opening.<br />

Symphony’s panel of about<br />

15,000 mobile device users<br />

tracks media consumption<br />

where users are, whether<br />

that’s at home, in the car, or<br />

in the parking lot at Target.<br />

Netflix, for its part, remains unconcerned. A company<br />

spokeswoman declined to comment on the data Wurtzel<br />

mentioned, but said in an email that “generally speaking,<br />

these kinds of traditional ratings don’t matter in a world<br />

where success isn’t measured by specific time slot. They are<br />

especially irrelevant on a subscription service that doesn’t sell<br />

ads. We measure success by subscriber numbers and hours<br />

people watch, and we do release those figures quarterly.”<br />

You could argue Netflix needn’t worry about ratings<br />

because it doesn’t have to worry about setting advertising<br />

pricing. But other subscription networks — HBO,<br />

Showtime, or Starz, to name a few — receive Nielsen<br />

ratings, which are a barometer of how their original<br />

content is received. Those numbers justify the cost of<br />

producing original programming. And considering Netflix<br />

has said it hopes to double the number of original series<br />

in the next year, it will be valuable to know whether or<br />

not the company is investing shrewdly in content, or just<br />

producing an endless stream.<br />

Netflix’s Most Viewed Shows of 2016<br />

by millions of viewers<br />

Fuller House 8.79m<br />

Source: Symphony Advanced Media<br />

Orange is the new black 7.18m<br />

Marvel’s Daredevil 3.6m<br />

House of cards 3.26m<br />

Marvel’s Jessica Jones 2.83m<br />

unbreakable Kimmy schmidt 2.79m<br />

F is for Family 1.81m<br />

Master of None 1.27m<br />

Narcos 1.14m<br />

Grace & frankie 1.09m<br />

12 DIMENSION

HELLO,

MR. ROBOT<br />

ASKS THE RIGHT<br />

QUESTIONS ABOUT<br />

HOW, EXACTLY,<br />

WE’RE GOING TO<br />

CHANGE THE WORLD.<br />

“Hello, friend.” That’s the first line of Mr. Robot, as<br />

its protagonist, Elliot Alderson — a cybersecurity engineer<br />

and hacker — hails the viewer before launching<br />

into his manifesto:<br />

What I’m about to tell you is top-secret. A conspiracy bigger<br />

than us all. I’m talking about the guys no one knows about.<br />

The guys that are invisible. The top one percent of the top one<br />

percent. The guys that play God without permission. And now<br />

I think they’re following me.<br />

These opening thirty seconds establish Mr. Robot’s two<br />

centers of gravity: the 1 percent are destroying the world,<br />

and our narrator can’t always discern reality from fantasy.<br />

FRIEND<br />

BY JEN HEDLER PHILLIS

WHAT I’M ABOUT TO TELL<br />

YOU IS TOP-SECRET. A<br />

CONSPIRACY BIGGER THAN<br />

US ALL. I’M TALKING<br />

ABOUT THE GUYS NO ONE<br />

KNOWS ABOUT. THE GUYS<br />

THAT ARE INVISIBLE. THE<br />

TOP ONE PERCENT OF<br />

THE TOP ONE PERCENT.<br />

THE GUYS THAT PLAY GOD<br />

WITHOUT PERMISSION.<br />

AND NOW I THINK THEY’RE<br />

FOLLOWING ME.<br />

Sam Esmail’s Mr. Robot came as a surprise when it<br />

premiered last year: not only does the series stand out<br />

from the USA Network’s typical programming — handsome<br />

men in nice clothes either enforcing or evading the<br />

law — but it also asks viewers to root for an anticapitalist,<br />

drug-addicted protagonist, who may or may not be imagining<br />

most of what happens to him as he attempts to take<br />

down one of the world’s largest corporations and seriously<br />

disrupt “the system” in the process.<br />

Mr. Robot took revolution prime time, and the Left<br />

should pay attention to what it has to say.<br />

IF TYLER DURDEN WERE A HACKER<br />

On a basic level Mr. Robot functions as political allegory,<br />

indexing progressive movements’ failure to enact large-scale<br />

change. The first season broadly explores two methods for<br />

achieving social transformation as Elliot (recent<br />

Emmy winner Rami Malek) and his<br />

childhood friend Angela (Portia Doubleday)<br />

work independently to get revenge on E Corp,<br />

a multinational corporation too big to fail.<br />

They hate the company because it caused<br />

a chemical spill that killed Elliot’s father<br />

and Angela’s mother. The corporate players<br />

have, of course, done no time and paid no<br />

settlements, and their surviving victims are<br />

drowning in medical debt that E Corp,<br />

conveniently, also owns.<br />

In the first episode, Mr. Robot (Christian<br />

Slater), recruits Elliot to join a hacker collective<br />

called fsociety, which is preparing to break into E<br />

Corp’s files and delete all its debt records. There’s something<br />

off about Mr. Robot: no one speaks directly to him except<br />

Elliot, and, when Mr. Robot speaks, characters often<br />

respond directly to Elliot. Although viewers picked up<br />

on this immediately, it takes Elliot most of the first season<br />

to realize that Mr. Robot is his very own Tyler Durden.<br />

The tension between the audience’s suspicions of Mr.<br />

Robot’s reality and Elliot’s unwillingness to acknowledge<br />

this makes fsociety’s plan to rid the world of debt feel<br />

hallucinatory: we cannot trust anything we see on screen.<br />

Elliot’s drug addiction contributes to the sense of unreliability.<br />

He goes cold turkey just before breaking into<br />

E Corp’s server farm to install a raspberry pi that will<br />

corrupt the plant’s thermostats and destroy their data.<br />

The withdrawal-induced dream sequence calls into question<br />

whether the heist actually happened or if it is another<br />

of our narrator’s fantasies.<br />

Meanwhile, Angela is busy trying to convince a lawyer<br />

to reopen the wrongful death lawsuit against the company.<br />

She gets an outgoing executive to testify to his participation<br />

in the spill; and, impressed with her negotiating skills and<br />

fearlessness, he recruits her. Believing she can leverage her<br />

position within E Corp to get justice for chemical-spill<br />

victims, Angela takes the offer and joins the public relations<br />

department — just when fsociety successfully completes it<br />

mission, throwing the corporation into a tailspin.<br />

Season two finds the main characters in defensive<br />

positions: rather than intensifying their assault on E Corp,<br />

fsociety hacks the FBI to stay ahead of their investigation.<br />

16 DIMENSION

Angela has since positioned herself in E Corp’s risk management<br />

department, but her boss knows that she was<br />

involved in the lawsuit and won’t trust her with damaging<br />

company information. She finally steals the data she<br />

needs, only to discover that the government regulators<br />

are E Corp pawns.<br />

As we follow the exploits of Elliot and Angela, the<br />

show encourages us to connect Mr. Robot’s plot elements<br />

to real-world corollaries. Fsociety is Anonymous and<br />

Occupy; E Corp’s logo is identical to Enron’s, and the<br />

computers it builds, the insurance it sells, and the banks<br />

it runs makes it interchangeable with Apple, Lehman<br />

Brothers, and Wells Fargo.<br />

In the second season, the production team re-cuts,<br />

splices, and dubs over news footage to update us on the<br />

state of the world post-hack. We see Barack Obama say,<br />

“The FBI announced today that Tyrell Wellick and fsociety<br />

engaged in this attack.” (No, the media-friendly president<br />

did not record the clip himself.) Images of riots and strikes<br />

appear in news reports about the ongoing crisis. Edward<br />

Snowden gives his take on the FBI investigation.<br />

The integration of actually existing political figures into<br />

the plot of Mr. Robot heightens its hallucinatory feel. Mr.<br />

Robot’s world is our world, shifted just a few degrees.<br />

This allows Esmail to dramatize the two lines of attack<br />

taken up by the American left in recent years — protest<br />

and change from within — and how they have been diverted<br />

or captured by the combined power of capital<br />

and the state.<br />

Both fsociety and Angela find themselves more directly<br />

at odds with elements of state power than their real target —<br />

financial capital — mirroring what happened<br />

to both the Occupy movement and<br />

the Sanders campaign. After all, Occupy<br />

wasn’t cleared by Goldman Sachs; it was<br />

the police, under the cover of public safety.<br />

Attempts to reoccupy the park and build<br />

permanent camps have been blocked by<br />

police, not capital.<br />

Likewise, it’s business as usual at the<br />

DNC. Listening to Hillary Clinton’s<br />

campaign speeches or considering her<br />

bland vice presidential nominee, you’d<br />

never know that a social democratic insurgency rocked<br />

the party this year. And while hope remains for downticket<br />

candidates, the trouble that plagued Our Revolution’s<br />

launch underlines the difficulty of enacting change from<br />

within a capitalist party.<br />

But treating Mr. Robot as a show that bears a one-toone<br />

resemblance to contemporary life misses the point.<br />

The bleak picture Esmail paints of contemporary revolution<br />

isn’t designed to depress us, it’s designed to force us<br />

MR. ROBOT TOOK<br />

REVOLUTION PRIME TIME,<br />

AND THE LEFT SHOULD<br />

PAY ATTENTION TO WHAT<br />

IT HAS TO SAY.<br />

17

MR. ROBOT IS DESIGNED TO<br />

FORCE US TO CONFRONT<br />

HOW WE ENGAGE WITH<br />

POLITICS, CAPITAL, AND<br />

OUR BEST (AND WORST)<br />

UTOPIAN IMPULSES.<br />

to confront how we engage with politics, capital, and our<br />

best (and worst) utopian impulses.<br />

MEDIATION IS THE MESSAGE<br />

Mr. Robot is made from popular culture. While Fight<br />

Club and American Psycho are its most obvious forebears,<br />

it also draws on Lolita, Back to the Future II, V for Vendetta,<br />

Taxi Driver, Raising Arizona, Breaking Bad, Fringe, Alf,<br />

and a hundred others.<br />

Culture critics call this pastiche — a type of representation<br />

Frederic Jameson famously decried as “blank parody.”<br />

Jameson argues that pastiche removes its cultural references<br />

from their historical moment, erasing history — and therefore<br />

politics. The recycled surface of pastiche blocks the<br />

audience’s capacity to engage politically with works of art.<br />

Reasonable people can — and do — disagree with<br />

Jameson’s assessment. Mr. Robot certainly offers a compelling<br />

counterexample: its use of pastiche doesn’t mask the<br />

relationship between viewers and politics,<br />

it reminds them that this is, in fact, how<br />

they encounter capitalism everyday.<br />

The final moments of the first season<br />

drive this point home. We discover that<br />

Whiterose, the leader of the Chinese hacker<br />

group Dark Army, works with E Corp CEO<br />

Phillip Price. As they discuss fsociety’s success,<br />

Price admits, “of course” E Corp knows who<br />

pulled off the hack and that they will “handle<br />

that person as we usually do.”<br />

The scene establishes two things: it reveals that<br />

White rose operates at the highest levels of both<br />

the anticapitalist hacker movement and the business world.<br />

It also shows the extent of E Corp’s power: they know<br />

who is responsible for the attack, hinting that they perhaps<br />

even knew it was coming. This seeming<br />

omniscience underlines how “the guys that<br />

are invisible,” whom Elliot references at<br />

the beginning of the season, have remained<br />

invisible: there’s another layer of power<br />

behind the one fsociety just took down.<br />

This scene handily sets up season two:<br />

new villains, new plots, a broader, more<br />

global perspective. It also plays into our<br />

cultural obsession with conspiracy theories.<br />

Across the political spectrum, frustrated<br />

people devise improbable explanations for<br />

the world’s problems. Whether it’s Alex<br />

Jones’s New World Order, the Illuminati<br />

mess, or 9/11 truthers, everyone — right,<br />

center, and left — finds comfort in having<br />

a faceless enemy to blame. But we don’t<br />

need a conspiracy. In life, as in Mr. Robot,<br />

something does stand between us and the<br />

real players, protecting people like Price<br />

and Whiterose from the underclasses.<br />

In a financialized economy, we increasingly<br />

deal with virtual wealth — money,<br />

stocks, bonds, mortgages — more than we<br />

do with material. This doesn’t mean that there was ever<br />

a time where capitalism wasn’t mediated — the money<br />

form as a general equivalent, in Marx’s words, has been<br />

with us all along.<br />

But these representational instruments have, in recent<br />

decades, exploded. To give just one example, the 2008<br />

crisis was brought on by financial products that shed<br />

their connection to the thing itself: a house becomes a<br />

mortgage, which is sliced up and repackaged with other<br />

slivers of homes, and sold. These assets then get sliced up<br />

even further, and resold at inflated prices,<br />

while investors get in on the game buying<br />

and selling insurance.<br />

The levels of mediation spiral higher<br />

and higher until we are no longer dealing<br />

with the thing itself, but — as in a pastiche<br />

— recycled material that is completely<br />

disconnected from the object it was designed<br />

to represent.<br />

It’s nearly impossible to represent this;<br />

much easier to show Price and Whiterose<br />

pulling the strings. Mr. Robot’s second<br />

season increasingly uses these shady powerbrokers’<br />

scheming to move the story along,<br />

presenting them — and not the structure<br />

of the economy — as Elliot’s real enemy.<br />

This ultimately dulls the political intervention<br />

Mr. Robot might make — at least on<br />

the level of plot.<br />

But as long as Mr. Robot underlines and<br />

illustrates that something always mediates<br />

our relationship to power, the show’s politics<br />

will be worth thinking about, and,<br />

indeed, engaging in.<br />

18 DIMENSION

CAN AN INSURGENT<br />

COLLECTIVE REALLY<br />

CHANGE THE WORLD?<br />

SILENT OBSERVERS<br />

From the moment Elliot addresses the audience as “friend,”<br />

viewers are implicated in the actions that unfold onscreen.<br />

Season two takes the audience’s involvement a step further:<br />

as Elliot is forced to listen to a tertiary character ramble<br />

on, his voiceover implores viewers to tune out the speech<br />

and search his apartment for clues to Mr. Robot’s plans.<br />

The camera obligingly moves up to ceiling level and<br />

slowly scans the set.<br />

Elliot asks us to intervene, to help him figure out what<br />

his alter ego has in store. We should do as he asks and<br />

apply our answers to our world.<br />

Granted, these answers aren’t easy coming. The show’s<br />

political takeaway isn’t always clear, and it hesitates in<br />

showing the hack’s human costs. We hear from news<br />

reports that the attacks devastated the economy, but Esmail<br />

doesn’t give viewers much more. Elliot questions whether<br />

the revolution had positive effects, and we are shown long<br />

lines for an ATM and a massive swap-meet that seems<br />

to have popped up as an alternate economy.<br />

None of this seems to touch the main characters however<br />

— all of whom are engaged in high-end service- and<br />

creative-sector work like cybersecurity, sales, and public<br />

relations. At worst, they have to wade through a protest<br />

before enjoying their expensive dinners.<br />

The characters’ position in the economy, on the one<br />

hand, gives them access to some of contemporary capitalism’s<br />

most important nodes: Elliot can plant viruses directly<br />

in corporate servers; Angela can access E Corp’s files to<br />

document their malfeasance.<br />

But their failure to enact positive and meaningful change<br />

raises questions about the limits of the creative class’s<br />

political and economic engagement. Can an insurgent<br />

collective really change the world?<br />

Esmail raises this question when Angela encounters an<br />

old friend of her father’s. He criticizes her for joining E<br />

Corp and implies that she traded sex for promotions. She<br />

responds angrily, throwing his working-class status in his<br />

face: “You’re a plumber. Right, Steve? You had what, sixty<br />

years at life? And that’s the best you could come up with?”<br />

Neither character looks great after this exchange — he’s<br />

a hateful misogynist; she’s a smug classist. The audience<br />

isn’t meant to side with either.<br />

So far Mr. Robot has refused to decide if the fsociety<br />

revolution is good or bad. And that’s not a bad thing. By<br />

relentlessly presenting us with popular-cultural representations<br />

of capitalism and resistance to it, it demands that<br />

we think through what new shapes a radical challenge to<br />

capitalism might take.<br />

Should we organize only those who have a “direct”<br />

relationship to production? Should we follow Kim Moody<br />

and focus on logistics? Is there hope for an insurgent<br />

campaign within a capitalist political party? Can a horizontal<br />

organization like Occupy do anything more than<br />

temporarily inconvenience the bankers? Should we all<br />

don masks and learn to code?<br />

Mr. Robot doesn’t offer answers. But for a network whose<br />

biggest hit before this was a legal drama called Suits, we<br />

should welcome every cultural product that raises these<br />

kinds of questions, pushing economic inequality, corporate<br />

malfeasance, and the cozy relationship between business<br />

and politics into the light. Even if Esmail isn’t interested<br />

in his characters’ politics, his viewers are.<br />

19

Sense8 and the failure of the<br />

global<br />

imagin<br />

ation<br />

by claire light<br />

How do you imagine a life you could never live? Though not really<br />

a theme, this problem is at the heart of Netflix’s new original<br />

series Sense8, created by the Wachowskis and J. Michael Straczynski,<br />

and heavily influenced by Tom Tykwer. Like many fantastical or science<br />

fictional premises, Sense8’s premise is a wish fulfillment: not — as<br />

is typical of this genre and the Wachowskis’ earlier work — the wish<br />

fulfillment of the disempowered middle school nerd stuffed into a<br />

locker, but rather the Mary Sue desire of a mature, white American<br />

writer/auteur who has discovered that an entire world is “out there,”<br />

one that the maker doesn’t know how to imagine.<br />

The premise in a nutshell: humanity has evolved a new subspecies,<br />

the “sensate,” who can share the thoughts, feelings, memories, skills,<br />

and experiences of other sensates. A sensate can “give birth” to a group<br />

of adult sensates, tying them together into a “cluster,” that can and<br />

does access each other without having to come in physical contact<br />

first. The cluster must be composed of eight sensates who were all<br />

born at the exact same time, which necessarily means that they are<br />

scattered all over the world. They can use each other’s languages,<br />

knowledge, and skills, and experience each other’s experiences firsthand.

You can see already how incredibly attractive these<br />

abilities would be to Americans who wish to depict<br />

a new global status quo, but grew up monolingual in<br />

an imperialist center.<br />

I’m describing, of course, the Wachowskis, who share<br />

entire writing and production credits with J. Michael<br />

Straczynski, but are the obvious spiritual core and<br />

drivers of this piece. Very little of Straczynski’s earlier<br />

work in superhero cartoons, space opera, and short-arc<br />

TV drama shows up here, except his expertise with the<br />

television format. Don’t get me wrong, I’m impressed<br />

with his light touch. You don’t see his hand in this at<br />

all, and I give entire credit and blame for this series to<br />

the Wachowskis, whose vision shines through. (Much<br />

more apparent is the influence of Tom Tykwer, who<br />

only directed two episodes, but whose pacing and<br />

elegiac grittiness is felt throughout.)<br />

The Wachowskis step onto the stage here as fully<br />

developed aesthetic internationalists, embracing the<br />

equality of diverse world cultures, and espousing the<br />

universality of the human experience. You can see<br />

the Wachowskis’ development into this — philosophy?<br />

— throughout their oeuvre, pushed by a desire<br />

to depict true diversity.<br />

It’s something you can see in the Matrix trilogy already,<br />

which was limited by the Wachowskis’ extremely<br />

limited white American perspective. The works they<br />

adapted subsequently (V for Vendetta, Speed Racer,<br />

Ninja Assassin) were training wheels: the developing<br />

Wachowski worldview refracted through international<br />

pop culture artifacts. Cloud Atlas feels like a culmination<br />

of this growth, the moment they discovered where they<br />

really wanted to go: towards a philosophical simultaneity<br />

through extremely diverse global cultures. In<br />

Sense8 you see them finally taking the training wheels<br />

off and attempting to originate their own simultaneous,<br />

diverse-culture-unifying fictions.<br />

It’s a beautiful vision, if you believe in universality.<br />

Let’s assume for a moment that you do. It’s a deeply<br />

worthy, exciting, and — dare I say it? — moral ambition.<br />

And it half-succeeds; which means it also half-fails.<br />

There should be word for the exhilaration of a halfsuccess<br />

coupled with the glowing disappointment of<br />

the half-failure, that two-sided coin. People who don’t<br />

speak German would say that there must be a longass<br />

German word for it. There isn’t, but German has<br />

the virtue of allowing someone to make a half-assed<br />

attempt at coining it. Ehrgeitzversagensschoene? I<br />

mention this, because this is one of the primary failures<br />

of the show: it attaches itself to Americans’ perceptions<br />

of how things are in other idioms, as much as,<br />

or more than, it attaches to how things actually are.<br />

To put it plainly: Sense8’s depiction of life in nonwestern<br />

countries is built out of stereotypes, and of<br />

life in non-American western countries is suffused<br />

with tourist-board clichés. The protagonist in Nairobi<br />

is a poor man whose mother has AIDS and whose<br />

life is ruled by gangs; in Mumbai we have a woman<br />

in a STEM career marrying a man she doesn’t love<br />

and engaging in Bollywood dance numbers; in Korea<br />

we have a patriarchally oppressed wealthy corporate<br />

woman who also happens to be a kickass martial artist;<br />

in Mexico City we follow a telenovela actor. London<br />

and Reykjavik are filmed using tourist locations<br />

and anonymous interiors.<br />

Worse, the filmic clichés of each country are brought<br />

to bear on the production in each location — each<br />

organized by a different director: Nairobi is sweaty,<br />

garish, earth-toned, radiantly shabby; Mumbai is<br />

multicolored, and Hindu iconned, full of the jewelry,<br />

silks, flowers, and jubilant crowds that burst out of<br />

classic Bollywood; Seoul is clean to the point of sterility,<br />

with little patches of grass and mirrors and windows<br />

everywhere, a grey, hi-tech aesthetic; Mexico City is<br />

jewel-toned, rife with skulls, full of melodrama deliberately<br />

reminiscent of the telenovela; etc. I believe,<br />

quite literally, that the filmmakers primarily learned<br />

22 DIMENSION

about these other cultures through their films, and<br />

considered that enough.<br />

And finally, the pop-cultural elements of the show are<br />

all American. There’s no evidence of local or national<br />

culture influencing how the non-American characters<br />

view themselves or live their lives. The Kenyan sensate<br />

idolizes Jean-Claude Van Damme (who is, granted, not<br />

American, but known for his role in American action<br />

films). The German sensate claims Conan the Barbarian<br />

quotes as his personal philosophy. The Icelandic DJ<br />

in London puts on 4 Non Blondes’ hideous anthem<br />

“What’s Goin’ On?” and infects the entire cluster with<br />

a dancing/singing jag. Where there’s no American<br />

cultural lead — in Korea and Mexico, and even in<br />

the Ganesh-worshipping Indian sensate’s life — the<br />

characters’ life philosophies are a blank.<br />

The Wachowskis take advantage of the apparent<br />

international ascendancy of American pop culture to<br />

unify disparate cultures, when the way American pop<br />

works on non-western cultures is often counterintuitive<br />

to Western minds. Sense8 also displays a profound<br />

lack of recognition of local pop cultures even when<br />

they would definitely have influenced such characters.<br />

In the show, American pop is specific, non American<br />

pop is generalized and clichéd, as in the Bollywood<br />

dance, or entirely absent.<br />

The universality being promoted here is a universality<br />

of American ideas, American popular culture,<br />

American world views. It’s like Stephen Colbert’s<br />

idea of freedom of religion:<br />

“I believe that everyone has the right to their own<br />

religion, be you Hindu, Jew, or Muslim. I believe<br />

there are infinite paths to accepting Jesus Christ as<br />

your personal savior.”<br />

If the entire show were an even spread of such thin<br />

notions, I could dismiss the show, or even enjoy it as<br />

as a guilty or problematic pleasure. But Sense8 has two<br />

great counter virtues.<br />

The first is in the depiction of the San Francisco<br />

sensate, which is the best representation both of the<br />

city and of that particular community that I’ve ever<br />

seen on TV. Nomi, a trans woman, is first seen wandering<br />

through a very locally-informed San Francisco<br />

cityscape during Pride weekend. At every level, the<br />

limning of Nomi’s character and the study of San<br />

Francisco are intimate, layered, nuanced, and above<br />

all, specific. Nomi doesn’t fall off a bike somewhere<br />

in San Francisco, she falls off a motorcycle in the<br />

Castro during the Dykes on Bikes parade, which she<br />

rides in every year with her girlfriend, a gesture of<br />

extreme importance to her identity. She doesn’t meetcute<br />

her girlfriend in a random park; she remembers<br />

The universality<br />

being promoted here<br />

is a universality<br />

of American ideas,<br />

American popular<br />

culture, American<br />

world views.<br />

23

a key moment early in their relationship where her<br />

girlfriend stands up for her against a hostile TERF<br />

during a picnic in Dolores Park.<br />

It’s the specificity that rings true to this San Franciscan,<br />

and that signals to all viewers that this world<br />

is real, and the character is alive within it.<br />

It’s a vision of how the entire show could have been,<br />

if the Wachowskis could have figured out in time<br />

how to bring this level of intimacy and specificity to<br />

their depiction of all the characters, and all the cities.<br />

Because Tom Tykwer, himself a Berliner, directs the<br />

Berlin sequences, you see a little bit of this familiarity<br />

in the locations chosen for that city and in the character<br />

of Wolfgang — his East German origins, his family’s<br />

Slavic name and orthodox religion, etc.<br />

But none of the other sensates, including the idealistic<br />

Chicago cop, bear anything close to the level<br />

of intimate knowledge or specific detail that Nomi<br />

or Wolfgang have. In fact, pay attention and you’ll<br />

see how generalizing the locations and incidents are.<br />

For example: in Nairobi, the sensate’s bus is robbed<br />

in what the characters themselves call “a bad area,” i.e.<br />

they don’t refer to the district by its name.<br />

But even this failure in the rest of Sense8’s world is<br />

countered somewhat by its second great virtue, which<br />

is that it commits totally to its clichés and rides them<br />

out to their conclusions. Thank the slow pacing for<br />

this. The entire 12-episode first season covers a story<br />

arc that would generally be covered in the first two<br />

episodes of any other show (the sensates are introduced,<br />

discover each other, start to learn the rules of their<br />

condition, meet their antagonist, and finally successfully<br />

pull off their first combined action). The very<br />

deliberation with which the story unfolds forces the<br />

writers to unpack details of each character’s life and<br />

situations that bring a kind of life and reality to the<br />

clichés they’re embedded in. Details are forced into the<br />

narrative — one by one in each character’s arc — and<br />

each character eventually becomes rooted in these<br />

details, even though they often come late in the season.<br />

For example, Kala, the Indian sensate in Mumbai,<br />

is characterized over simply at first: she is to marry a<br />

man she doesn’t love, and she is a dedicated worshiper<br />

of the Hindu elephant god, Ganesh. We don’t actually<br />

learn more large details about her, but in drilling<br />

down on these two things, we learn a great deal of<br />

anchoring detail: the marriage is not arranged, but<br />

a “love match;” with her boss’ son; whom she met at<br />

work; at a pharmaceutical company; where she works<br />

as a chemical engineer; because she has a master’s degree<br />

in chemistry. She worships Ganesh; not because<br />

she’s a benighted third world person but because she<br />

sees no conflict between science and spirituality; and<br />

because she had an experience of being lost as a child<br />

and then discovering a literal new perspective of the<br />

world through the eyes of a papier maché Ganesh<br />

parade float; as a consequence, she takes her sensate<br />

role in stride because she trusts that she is still seeing<br />

the world through Ganesh’s eyes.<br />

All of the characters get drilled down into in this<br />

way, to varying degrees, and all start to take on life<br />

and verisimilitude. The main problem with forcing<br />

this kind of life into characters is that the audience<br />

cannot trust its, for lack of a better word, authenticity.<br />

To return to Kala: we see her more than once visiting<br />

the temple of Ganesh where she has out loud, private<br />

conversations with the god, a la Are You There, God?<br />

It’s Me, Margaret. I don’t know whether or not Hindus<br />

are taught to converse vernacularly with their gods in<br />

their temples, but the extreme Americanness of the<br />

depiction warns me that the Wachowskis probably don’t<br />

know either. My suspicion is that they transposed an<br />

American Christian moment into an Indian Hindu<br />

one, without really finding out if the translation held.<br />

Moments like this are sprinkled throughout.<br />

The Wachowskis fail to examine characters in the<br />

characters’ own context. These are some of the basics<br />

of fictional world building and character development:<br />

you create the rules of the world, create the<br />

Sense8 commits<br />

totally to its clichés<br />

and rides them out to<br />

their conclusions.<br />

24 DIMENSION

worldview, situate the character in<br />

this worldview, pick out notes of<br />

the worldview for the character to<br />

hold as a personal philosophy, motivate<br />

the character according to that<br />

personal philosophy, and have the<br />

character act throughout the story<br />

in accordance with these motivations.<br />

Missing out on any of these<br />

layers — especially the first, broadest<br />

layer of cultural context — leaves<br />

you with a character that may or<br />

may not be alive, but whose motivations,<br />

worldview, and context are a<br />

blank. And most of Sense8’s characters<br />

are laboring within blankness.<br />

Again, they gain a certain amount<br />

of rootedness, but not one that is<br />

trustworthy, because they are rooted<br />

in this same cultural absence.<br />

Again, we need that fictional<br />

German word, to describe how<br />

I feel about what I can only call a failure of global<br />

imagination. The fact that the makers conceived of<br />

having a global imagination in the first place is, in<br />

itself, a triumph. The fact that they attempted to<br />

embody a global imagination in a television show is<br />

breathtaking. Given their approach, their failure to<br />

achieve that global imagination was inevitable.<br />

Because the very act of conceiving a global imagination<br />

is itself a function of the specifically American<br />

imagination. I “assumed” earlier that we agreed with<br />

the Wachowskis’ philosophy of the universality of<br />

human experience; but do we? Universality is a deeply<br />

western humanist idea that attaches particularly well<br />

to the US’s brand of Darwinist individualism. We<br />

all have — or should have — the same opportunities,<br />

the same basis. What we make of this is a function of<br />

our individuality. Culture is just happenstance; what’s<br />

important is our actions, our choices, etc. It’s a familiar<br />

refrain, and much of American anti-racism and social<br />

justice is based upon the idea of the even — the universal<br />

— playing field as an ideal to aspire to.<br />

But how universal is human experience, really? How<br />

empathetic can we be? We don’t really know how<br />

deep culture and environment go in the psyche. We<br />

don’t really know how different people can be. Our<br />

sciences — and especially our “soft” sciences, which are<br />

tasked with these questions — have barely scratched<br />

the surface of any answers, eternally stymied by their<br />

own deep-seated cultural biases, and the cultural bias<br />

of “science” itself. And the very idea of universalism<br />

is — o, irony! — too often a culturally imperialist idea<br />

imposed from outside upon cultures that share no such<br />

understanding of the world.<br />

The characters discuss their choices with one another,<br />

but nowhere is there any cultural misunderstanding<br />

of each others’ choices. Yes, they can each feel what the<br />

others are feeling, think what the others are thinking.<br />

But does that free each of them from their cultural<br />

context? Wouldn’t, instead, each of them be having<br />

profound identity crises based on the deepest sort of<br />

culture clash anyone has ever felt?<br />

“Universalizing” everything under an American<br />

idea — an American set of choices — is a contradiction<br />

in terms; one the Wachowskis underlined in Sense8<br />

through their collaborative process. All five directors<br />

who worked on the show are white men, except the<br />

Wachowskis. All are American except Tykwer, who<br />

has been working in Hollywood for years. All episodes<br />

in all locations were written by the Wachowskis and<br />

Straczynski — again, a white man and the Wachowskis.<br />

There seems to have been no thought of reaching out<br />

to, much less collaborating with, writers and directors<br />

from the cultures here represented.<br />

The great irony of this show is that it failed to<br />

do what the show itself depicts: allow people from<br />

disparate cultures to work together, influence each<br />

other, clash with each other, and to live moments of<br />

each other’s lives.<br />

In a discussion before I wrote this piece, disagreed<br />

with a friend about the handling of language in the<br />

show. I really appreciated the choice of having all<br />

characters speak English without forcing them all<br />

to speak English in cheap versions of their “native”<br />

accents. And, given that this was an American TV<br />

show, I didn’t expect the makers to force American<br />

audiences to read subtitles. My friend, however, pointed<br />

out that it would have been… well, less hegemonic for<br />

everyone to be actually speaking their own languages.<br />

Upon reflection, I have to agree that having the<br />

dialogue in non-English speaking countries translated<br />

would have offered the translators an opportunity<br />

for input about the content of the dialogue. And if<br />

the Wachowskis had hired writers from each culture<br />

to translate not merely the text but also the entire<br />

culture and idiom — up to and including changing<br />

plot points and points of view to better fit with the<br />

local culture of that character — this could have solved<br />

their whole problem.<br />

Whether or not you believe in the universality of<br />

human experience — whether or not you believe in<br />

25

The great irony of this<br />

show is that it failed to<br />

do what the show itself<br />

depicts: allow people<br />

from disparate cultures<br />

to work together,<br />

influence each other,<br />

clash with each other,<br />

and to live moments of<br />

each other’s' lives.<br />

a single global imagination — the only way to attempt<br />

to depict a true global imagination would be<br />

to create — in the writers room and on the directors’<br />

chairs — a facsimile of a sensate cluster. Just imagine<br />

it: eight equal auteurs, each in their own physical<br />

location and cultural context, striving together — and<br />

frequently pulling apart — to achieve a single, complex<br />

story on film. Even the failure of such an enterprise<br />

would have been far more ambitious, far more glorious,<br />

far more Ehrgeizversagensschoen, than the Sense8<br />

we actually got.<br />

There are four more seasons to go on this show,<br />

if the Wachowskis get their way. Season 2 completed<br />

filming this summer and all episodes are slated for<br />

release on Netflix in December 2016. Let’s hope that<br />

in the future their globalism is more than just an<br />

aesthetic decision.<br />

Bottom line: yes, watch it. Binge it. Its failure is far<br />

more interesting than the success of almost anything<br />

else happening at this moment. And it’s truly one of<br />

the most diverse shows on TV right now.<br />

26 DIMENSION

modern<br />

marvel<br />

why netflix’s<br />

Luke cage is<br />

the superhero<br />

we really<br />

need now<br />

Cheo Hodari Coker wanders<br />

the aisles of Midtown Comics, a two-story<br />

megastore just east of New York’s Hell’s<br />

Kitchen. Despite the muggy July morning,<br />

he’s wearing a hooded sweatshirt, and<br />

he mops the sweat from his forehead as<br />

he peruses the new releases and graphic<br />

novels. After a few minutes he adjusts the<br />

messenger bag on his left shoulder, pads<br />

silently up to the second floor, and gets to<br />

the real reason he’s here — hunting down<br />

back issues of Luke Cage. One of Marvel’s first African<br />

American superheroes, Cage was introduced in response<br />

to the blaxploitation films of the 1970s. A New Yorker<br />

like virtually every other earthbound Marvel character,<br />

he lived in Harlem, just a couple miles north of this very<br />

store. While he never achieved the blockbuster, iconic<br />

status of some of his mask-and-cape-wearing brethren,<br />

Cage enjoyed a cult following for decades.<br />

But Coker is coming up blank. Midtown Comics doesn’t<br />

carry many classic Luke Cage graphic novels. They don’t<br />

have Luke Cage #5, the first appearance of supervillain and<br />

Cage nemesis Black Mariah. Ditto Marvel Premiere #20,<br />

which introduces Cage’s frenemy, the cyborg cop Misty<br />

Knight. The store had some Luke Cage action figures, but<br />

it recently ran out of them.<br />

“Well, I’m happy to see he’s selling out,” the man tells<br />

an apologetic staffer.<br />

“I guess it’s because they’re promoting the TV show<br />

coming out in September,” the staffer says.<br />

“Yeah, yeah, no doubt,” the man says, in a voice that hints,<br />

“Please ask me who I am and why I seem so invested in<br />

this character.” The staffer does not bite, so he never learns<br />

that, in fact, the man standing before him is the writer<br />

and showrunner bringing Luke Cage to the small screen.<br />

As with most Marvel properties, comics fans have<br />

pored over any scrap of information they can find about<br />

the forthcoming show; they know that it comes to Netflix<br />

on September 30, and they know that Mike Colter will<br />

play the title role — a wrongfully imprisoned ex-convict<br />

with bulletproof skin — but not much else. There’s a part<br />

of Coker that’s dying to shed his anonymity, to expose<br />

the secret identity beneath his burly frame, Muhammad<br />

Ali T-shirt, and Stanford hoodie, to pull the laptop out of<br />

his messenger bag and show the rough cut of the trailer<br />

he has just received from Netflix’s marketing department.<br />

Instead, Coker picks up some books for himself — a Black<br />

Panther compilation and a new Power Man and Iron<br />

Fist — and shuffles out of the store.<br />

TV viewers first met Cage as the on-again off-again love<br />

interest in Jessica Jones, Marvel’s previous collaboration with<br />

Netflix. That show didn’t just reinforce that comics could<br />

profitably extend into the world of premium television; it<br />

expanded the very notion of superheroism itself. Led by<br />

creator Melissa Rosenberg, it revolved around a PTSDsuffering,<br />

borderline alcoholic PI facing down her rapist,<br />

a supervillain who could control his victims’ thoughts and<br />

actions. The plot touched on gaslighting, victim-blaming,<br />

abortion, and an almost literal case of testosterone poisoning;<br />

it all suggested a world in which heroes didn’t have<br />

to save the universe. Just being a woman amid the many<br />

varieties of male vanity and violence was heroic enough.<br />

Cage’s heroic journey is similarly personal. His mission<br />

isn’t to track down Doctor Doom like he did in the ’70s<br />

but to accept his responsibility to help defend Harlem<br />

from the many forces that threaten it. Coker says he was<br />

inspired to serve as showrunner when he realized the<br />

ramifications of a series about a black man with impenetrable<br />

skin and how that might empower him to take<br />

on both criminals and crooked authority figures. “The<br />

main reason people don’t speak out, their main fear, is<br />

getting shot,” Coker says. “So what happens if someone<br />

is bulletproof? What happens if you take that fear away?<br />

That changes the whole ecosystem.”<br />

Along the way, characters wrestle with their use of<br />

the n-word, sing the praises of the ’90s-era Knicks, and<br />

discuss the impact that urban planner Robert Moses,<br />

the Cross Bronx Expressway, and US senator Daniel<br />

Patrick Moynihan’s policy of “benign neglect” had on<br />

New York’s black community. The script name-checks<br />

such black cultural and political figures as Ralph Ellison,<br />

Donald Goines, Zora Neale Hurston, Adam Clayton<br />

by jason tanz

REPEAT DEFENDER<br />

Luke Cage has long been a mainstay of Marvel<br />

Comics’ all-too-human street-level roster.<br />

1972<br />

VICTORIA TANG<br />

Hero for Hire<br />

In this original issue, an<br />

innocent Carl Lucas lands in prison, where a<br />

botched experiment gives him superstrength<br />

and bullet proof skin.<br />

1974 Defenders<br />

After breaking out of prison,<br />

Cage gets roped into this “non-team” to stop<br />

bad guys like the unabashedly racist supervillain<br />

group Sons of the Serpent.<br />

1978<br />

Power Man and<br />

Iron Fist<br />

Cage rebrands himself and partners with martialartist<br />

Iron Fist to provide superhuman security<br />

and investigative services.<br />

2001 Alias<br />

When Cage and Jessica<br />

Jones have a one-night stand, the P.I. gets<br />

pregnant. The two ultimately wed and become<br />

parents to a baby girl.<br />

2010 Thunderbolts<br />

Captain America puts Cage in<br />

charge of his own group of crime-fighters, which<br />

operates from a maximum-security island prison<br />

and rehabilitates supervillains.<br />

COURTESY OF MARVEL<br />

Powell Jr., and Crispus Attucks. There have been African<br />

American super heroes on our screens before — such as<br />

Wesley Snipes’ titular turn in Blade — but Luke Cage is<br />

the first to be surrounded by an almost completely black<br />

cast and writing team and whose powers and challenges<br />

are so explicitly linked to the black experience in America.<br />

“I pretty much made the blackest show in the history of<br />

TV,” Coker says, laughing.<br />

Not that he’s rebooted Do the Right Thing, exactly.<br />

Luke Cage is fundamentally a four-quadrant-seeking,<br />

crowd-pleasing, big-tent affair, like Empire, Power, or<br />

the Thursday-night Shonda Rhimes–fest on ABC. The<br />

success of those shows suggests that we may have finally<br />

entered a new epoch in the 21st century’s golden age of<br />

television. For years, the nascent medium of prestige<br />

TV drama was defined by what author Brett Martin has<br />

called difficult men — grimly captivating white guys like<br />

Tony Soprano, Don Draper, and Walter White, struggling<br />

to find a foothold in a culture and economy that<br />

were leaving them behind. That was before Netflix and<br />

Amazon and their respective breakout hits, Orange Is the<br />

New Black and Transparent, proved that hit dramas could<br />

move beyond straight white men.<br />

In part, this is a happy consequence of the TV wars. As<br />

a glut of competitors have pumped out a steady stream<br />

of compelling shows, executives are more motivated than<br />

ever to find programs that will stand out from the crowd.<br />

Subscription-based digital platforms, eager to reach into<br />

global markets and unburdened by skittish advertisers,<br />

are more willing to gamble on series that traditional<br />

networks might consider too risky. In the meantime,<br />

three decades of boundary-pushing television has created<br />

a more sophisticated audience, willing to watch<br />

characters that previous generations may have found<br />

alienating. “It evolves, but incredibly slowly,” says<br />

Jessica Jones’ Rosenberg. “I think we are beyond<br />

overdue for both Luke Cage and Jessica Jones.”<br />

Compared to his big-screen Marvel counterparts,<br />

like Iron Man and Thor, Netflix’s<br />

Luke Cage might seem like a low-stakes<br />

superhero. He isn’t out to save the universe,<br />

and he doesn’t wear a flashy costume; he<br />

rarely even uses his superpowers, which<br />

are presented more as a behavioral<br />

30

quirk than a defining characteristic of his personality. He’s<br />

deeply flawed, haunted by his past, and, as Colter says,<br />

might pick up women at a funeral. But that’s precisely<br />

what makes him so heroic. He’s working on it, struggling<br />

to accept himself in the face of a world that keeps pushing<br />

him toward invisibility. “So many times, black protagonists<br />

have to be holier than thou, but he’s not an angelic figure,”<br />

says John Singleton, the Boyz n the Hood director and a<br />

friend of Coker’s. “It’s the right time for this kind of hero.<br />

He’s so needed in the world.”<br />

WITH COKER’S COMIC-GEEK background<br />

underpinning his years of experience in TV and film,<br />

the role of Luke Cage showrunner fits him as snugly as<br />

a Spidey suit. But where Marvel’s superheroes tend to<br />

stumble into their powers by accident — radioactive spider<br />

bites, misbegotten nuclear tests — Coker didn’t have to<br />

wander into a malfunctioning laboratory to acquire his<br />

skills. He’d been actively accumulating them for decades.<br />

Coker started reading fantasy novels after his parents<br />

divorced and his mother went back to college and then<br />

law school. She usually brought Coker with her to the<br />

library, enforced quiet time that sparked a love of reading.<br />

When Coker was 10, a friend showed him a copy of<br />

Wolverine, the beginning of a seminal story arc written<br />

by Chris Claremont and arted by Frank Miller. The story<br />

starts with Wolverine sadly killing a grizzly bear, then<br />

goes on to depict a battle between the superhero and his<br />

fiancée’s yakuza father — a saga of regret and doubt, not<br />

just Technicolor beat-’em-up. Coker keeps all four issues<br />

of the series in his LA office for inspiration. “They were<br />

saying yes, this is an adolescent pastime, but that doesn’t<br />

mean we can’t imbue it with a sophisticated worldview,”<br />

he says of its creators.<br />

Comics didn’t just provide great stories but also a target<br />

for Coker’s obsessive tendencies, a wealth of back issues,<br />

in-jokes, and cross-references to hunt down and untangle.<br />

He had a similar response when his cousins introduced<br />

him to hip hop in the mid-1980s. Over time he came<br />

to think of it as superhero music. “It’s the attitude,” he<br />

says. “When I heard the Wu-Tang Clan, I always saw<br />

Captain America and the Avengers assembling as the<br />

camera swoops in.”<br />

Coker had his first chance to meet some of his heroes<br />

as an undergraduate writer for The Stanford Daily,<br />

where he conducted interviews with rappers like Ice<br />

Cube, KRS-One, and Ice T. Before he graduated, he was<br />

writing freelance articles for The Source, Vibe, and others,<br />

becoming an acclaimed and prolific member of the first<br />

wave of hip hop journalists. Over time, Coker began to<br />

see more parallels between the rappers he covered and the<br />

comics he loved. Like Marvel superheroes, rappers often<br />

had to navigate between their public personae and their<br />

private selves. During an interview for Vibe, Christopher<br />

Wallace told Coker that he lived a double life even before<br />

he became the rapper Notorious B.I.G.; to his mom he<br />

was “Chrissie-poo,” an innocent homebody, but when<br />

he sneaked out to sell drugs on the street corners, he was<br />

known as “Big Chris.” He even kept a spare outfit on the<br />

roof of his apartment building so he could change out of<br />

his school clothes without his mother realizing — a detail<br />

that reminded Coker of Spider-Man’s efforts to keep his<br />

superhero identity a secret from his aunt May.<br />

Eventually, Coker took<br />

up screenwriting. He was<br />

inspired in part by his uncle,<br />

Richard Wesley, who<br />

wrote the scripts for such<br />

landmarks of black cinema<br />

as Uptown Saturday Night<br />

and Native Son. Together,<br />

they wrote a fictionalized<br />

version of Tupac Shakur’s<br />

murder, called Flow. The film never got made, but it won<br />

Coker attention. Soon he was adapting Unbelievable, his<br />

biography of the Notorious B.I.G., into the feature film<br />

Notorious. That led to other work, including a job as a<br />

writer and coproducer for the Peabody- winning series<br />

SouthLAnd, under legendary showrunner John Wells, and<br />

later a stint as coexecutive producer on Showtime’s Ray<br />

Donovan; he calls the respective experiences “my graduate<br />

degree and my PhD.”<br />

It was around 2014, when Coker was doing a round of<br />

touch-ups on the screenplay for Straight Outta Compton,<br />

that Marvel started looking for a showrunner for Luke<br />

Cage. From the beginning, says Jeph Loeb, head of<br />

Marvel’s television division, the company was looking<br />

for someone who could not only entertain but also address<br />

issues of race: “What is going on in this country for blacks<br />

and whites, and how can we tell that story through the<br />

eyes of a superhero?” Marvel was in the midst of expanding<br />

its roster of nonwhite superheroes, including introducing<br />

a Muslim Ms. Marvel and a Latino Spider-Man.<br />

The company has since hired Ta-Nehisi Coates, author<br />

of the best-selling Between the World and Me, to pen the<br />

newest adventures of Black Panther, the supergenius ruler<br />

of a fictional African nation. (That character will soon<br />

appear in a film directed by Ryan Coogler, who helmed<br />

Fruitvale Station, about a victim of police violence, and<br />

Creed, the heroic saga of Apollo Creed’s son.) Still, this<br />

was Marvel’s first attempt to create a series or film with<br />

a black protagonist at its center, a responsibility that Loeb<br />

took very seriously. “If we can get one person to watch<br />

the show and to think differently about what it is to be<br />

a hero in the present day, and what it is to be a black hero,<br />

then that’s a victory,” he says.<br />

At his first meeting with Marvel, Coker brought a photograph<br />

of his grandfather, a Tuskegee Airman who had<br />

been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. “I talked<br />

about him being from Harlem,” Coker says. “Walking<br />

up the boulevards, you’d see Duke Ellington and Chick<br />

Webb and Lionel Hampton, just walking around. You<br />

saw superheroes every day.” Initially, Coker saw Luke<br />

Cage exploring a similar dynamic, the pressures of a<br />

known superhero operating in the real world, but Marvel<br />

wanted Cage to grow into his role as a superhero, not to<br />

The main reason people<br />

don’t speak out, their main<br />

fear, is getting shot. So what<br />

happens if someone is bulletproof?<br />

What happens if you<br />