Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

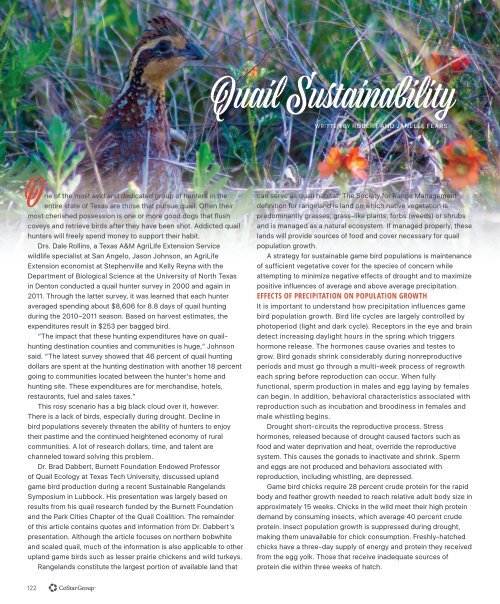

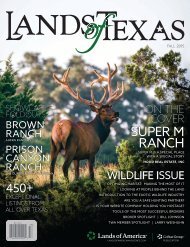

Quail Sustainability<br />

WRITTEN BY ROBERT AND JANELLE FEARS<br />

One of the most avid and dedicated group of hunters in the<br />

entire state of <strong>Texas</strong> are those that pursue quail. Often their<br />

most cherished possession is one or more good dogs that flush<br />

coveys and retrieve birds after they have been shot. Addicted quail<br />

hunters will freely spend money to support their habit.<br />

Drs. Dale Rollins, a <strong>Texas</strong> A&M AgriLife Extension Service<br />

wildlife specialist at San Angelo, Jason Johnson, an AgriLife<br />

Extension economist at Stephenville and Kelly Reyna with the<br />

Department of Biological Science at the University of North <strong>Texas</strong><br />

in Denton conducted a quail hunter survey in 2000 and again in<br />

2011. Through the latter survey, it was learned that each hunter<br />

averaged spending about $8,606 for 8.8 days of quail hunting<br />

during the 2010–2011 season. Based on harvest estimates, the<br />

expenditures result in $253 per bagged bird.<br />

“The impact that these hunting expenditures have on quailhunting<br />

destination counties and communities is huge,” Johnson<br />

said. “The latest survey showed that 46 percent of quail hunting<br />

dollars are spent at the hunting destination with another 18 percent<br />

going to communities located between the hunter’s home and<br />

hunting site. These expenditures are for merchandise, hotels,<br />

restaurants, fuel and sales taxes.”<br />

This rosy scenario has a big black cloud over it, however.<br />

There is a lack of birds, especially during drought. Decline in<br />

bird populations severely threaten the ability of hunters to enjoy<br />

their pastime and the continued heightened economy of rural<br />

communities. A lot of research dollars, time, and talent are<br />

channeled toward solving this problem.<br />

Dr. Brad Dabbert, Burnett Foundation Endowed Professor<br />

of Quail Ecology at <strong>Texas</strong> Tech University, discussed upland<br />

game bird production during a recent Sustainable Rangelands<br />

Symposium in Lubbock. His presentation was largely based on<br />

results from his quail research funded by the Burnett Foundation<br />

and the Park Cities Chapter of the Quail Coalition. The remainder<br />

of this article contains quotes and information from Dr. Dabbert’s<br />

presentation. Although the article focuses on northern bobwhite<br />

and scaled quail, much of the information is also applicable to other<br />

upland game birds such as lesser prairie chickens and wild turkeys.<br />

Rangelands constitute the largest portion of available land that<br />

can serve as quail habitat. The Society for Range Management<br />

definition for rangeland is land on which native vegetation is<br />

predominantly grasses, grass-like plants, forbs (weeds) or shrubs<br />

and is managed as a natural ecosystem. If managed properly, these<br />

lands will provide sources of food and cover necessary for quail<br />

population growth.<br />

A strategy for sustainable game bird populations is maintenance<br />

of sufficient vegetative cover for the species of concern while<br />

attempting to minimize negative effects of drought and to maximize<br />

positive influences of average and above average precipitation.<br />

EFFECTS OF PRECIPITATION ON POPULATION GROWTH<br />

It is important to understand how precipitation influences game<br />

bird population growth. Bird life cycles are largely controlled by<br />

photoperiod (light and dark cycle). Receptors in the eye and brain<br />

detect increasing daylight hours in the spring which triggers<br />

hormone release. The hormones cause ovaries and testes to<br />

grow. Bird gonads shrink considerably during nonreproductive<br />

periods and must go through a multi-week process of regrowth<br />

each spring before reproduction can occur. When fully<br />

functional, sperm production in males and egg laying by females<br />

can begin. In addition, behavioral characteristics associated with<br />

reproduction such as incubation and broodiness in females and<br />

male whistling begins.<br />

Drought short-circuits the reproductive process. Stress<br />

hormones, released because of drought caused factors such as<br />

food and water deprivation and heat, override the reproductive<br />

system. This causes the gonads to inactivate and shrink. Sperm<br />

and eggs are not produced and behaviors associated with<br />

reproduction, including whistling, are depressed.<br />

Game bird chicks require 28 percent crude protein for the rapid<br />

body and feather growth needed to reach relative adult body size in<br />

approximately 15 weeks. Chicks in the wild meet their high protein<br />

demand by consuming insects, which average 40 percent crude<br />

protein. Insect population growth is suppressed during drought,<br />

making them unavailable for chick consumption. Freshly-hatched<br />

chicks have a three-day supply of energy and protein they received<br />

from the egg yolk. Those that receive inadequate sources of<br />

protein die within three weeks of hatch.<br />

122