Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

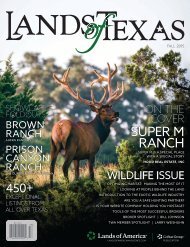

PROFILE<br />

ON THE GROUND RESULTS<br />

Bell estimates that the company has laid<br />

hundreds of miles of poly pipe through<br />

the years.<br />

“We offer a practical solution for what<br />

is one of many landowners’ biggest<br />

challenges,” Bell said, noting the majority<br />

of the company’s projects are in South<br />

<strong>Texas</strong> and West <strong>Texas</strong>. “We will tackle any<br />

project regardless of size. Nothing is too<br />

small—or too large.”<br />

Recently, the team installed 65 miles of<br />

two-inch pipe and 62 troughs on a ranch<br />

south of Marfa.<br />

“We tied into the wells. Then, we pumped<br />

the water to a reservoir at a higher elevation<br />

and used gravity flow to distribute it<br />

throughout the ranch,” Bell said.<br />

On another ranch south of Carrizo<br />

Springs that has operated since the<br />

1800s, the company installed 10 storage<br />

tanks with capacities ranging from 50,000<br />

gallons to 65,000 gallons apiece to<br />

supply the needs for a mixed livestock<br />

and wildlife operation.<br />

A ranch, located south of Alpine,<br />

needed 250,000 feet of pipe run over<br />

the top of mesas and down into valleys<br />

to supply its quail/wildlife waterers.<br />

The project has been implemented in<br />

phases over the past six years. The ranch<br />

manager recently showed Bell the results<br />

of their work.<br />

On the tour, the duo flushed a covey<br />

about every 150 yards. When Bell<br />

expressed his delight, the ranch manager<br />

told him to wait until they got to the<br />

bottom of Cartwright Canyon.<br />

“We flushed a covey that had about 150<br />

birds,” Bell said. “I’ve never seen anything<br />

like it in my life.”<br />

It demonstrated what quail managers<br />

have long told him.<br />

“To have a good quail crop, you need three<br />

things: water, water and water,” Bell said.<br />

Seeing the land’s bounty also served<br />

as a reminder of why this business means<br />

much more than a mere bottom line.<br />

“It’s rewarding to ‘put water where it<br />

isn’t—and see what Mother Nature and<br />

land managers do with the opportunity,”<br />

Bell said. °<br />

LEGACY OF THE <strong>LAND</strong><br />

Looking back over his life, Kenneth Bell recognizes that the<br />

land and the people who cared for it have shaped his life from<br />

the beginning.<br />

“I grew up in a wonderful time and a wonderful way in West <strong>Texas</strong>. I was<br />

fortunate. Our family was solidly middle class. We weren’t poor, but we<br />

didn’t just throw money around either. My dad worked in the oilfield and my<br />

mom was a teacher. My parents and my ranching uncles were all college<br />

educated. School was important.<br />

I grew up in Odessa, but spent weekends, holidays and all my summers<br />

on the family’s ranches. Some of my earliest memories are being on<br />

horseback and helping move stock. I was probably 4 or 5. We had a job<br />

to do.<br />

When we were done, my cousins and I would swim in tanks, play tag<br />

on horseback chasing each other through the arroyos. The Fort Stockton<br />

place was 120 sections and as kids we would have sworn we rode over<br />

every acre. Looking back, though, I figure we maybe covered the same<br />

5,000 acres over and over.<br />

While I spent time in Fort Stockton, I spent most of my time on the ranches<br />

in Fort McKavett and Menard. That uncle was my mother’s brother. His<br />

nickname for me was ‘Rat Bastard.’ It was a term of endearment. (I think.)<br />

We were really close.<br />

My uncle ran sheep and cattle on the place at Menard. On the Fort<br />

McKavett ranch, he couldn’t run sheep because of bitterweed, which<br />

poisoned them, so he ran Angora goats instead. By the time I was 14 and<br />

my cousin was 10, we’d stay out at Fort McKavett by ourselves. Our main<br />

jobs were doctoring screw worms, fixing water gaps—in the rare cases it<br />

rained—and scrubbing out the water troughs so the water was clean.<br />

The goats were sheared in August and mohair was a big cash crop. It<br />

was important that they had plenty of clean water to drink because clean<br />

water caused them to purge the lanolin, the grease, from their hair. The<br />

less grease that was in their hair, the less dirt and trash it attracted. Dirty<br />

hair took a big price hit, so cleaner was better.<br />

We’d ride all day and come home for lunch. We’d loosen the horses’<br />

girths, take off their bridles and let them graze in the yard, while we ate.<br />

There were no adults around. We had to learn to think for ourselves.<br />

When we were done for the day, we bathed in a water tank. We pulled<br />

the truck up close and jumped in from the cab—naked as jaybirds. When<br />

we were finished, we’d drive back hunting jack rabbits all along the way.<br />

Most kids now don’t have that kind of freedom. They’re not going to have<br />

those kinds of memories—and learn those inherent lessons of the land.<br />

I still have a ranch between Menard and London. It’s where we take our<br />

three kids, their spouses and our seven grandkids now. It means a lot to<br />

be able to pass those experiences along. Of course, they’re different than<br />

mine were, but they’re still valuable. In today’s world, they’re rare. It’s a<br />

blessing that my family has those roots and that chance.”<br />

148