TIL_Sommer_21-7-17

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

34<br />

THE MENTOR – Vaudeville Theatre<br />

It has been some while – a decade in<br />

fact – since F. Murray Abraham (playing<br />

Shylock for the RSC), plied his<br />

considerable talents on a British stage.<br />

Best remembered for his Oscar-winning<br />

turn as Salieri in Milos Forman’s film<br />

version of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, and<br />

as as the CIA’s Dar Adal in the TV series<br />

Homeland, it’s unlikely his star turn in<br />

The Mentor will put bums on seats or<br />

add lustre to his CV.<br />

In The Mentor, by German playwright<br />

Daniel Kehlmann, whose books in his<br />

home country outsell J.K. Rowling’s, he<br />

plays a waspish playwright called<br />

Benjamin Rubin who, at the age of 24,<br />

wrote a celebrated play on which his now<br />

evanescent reputation rests. Although<br />

studied in universities, the play is never<br />

revived and his career is on the skids.<br />

Yet in the opening scene, a<br />

contemporary playwright, Martin Wegner<br />

(Daniel Weyman) has just won the<br />

Benjamin Rubin award at a BAFTA like<br />

ceremony for his latest play, though why<br />

there is an award in his name is unlikely<br />

(a) given Rubin’s waning status, and (b)<br />

playwrights rarely, if ever, have major<br />

awards named after them.<br />

Be that as it may, we now flashback<br />

several years to a luxury villa where a<br />

wealthy arts foundation has, for a fee of<br />

10,000 euros, asked Rubin to mentor a<br />

work in progress by a self-satisfied,<br />

over-confident ‘new generation’<br />

playwright who turns out to be the very<br />

same Martin Wegner of the prologue.<br />

Jonathan Cullen.<br />

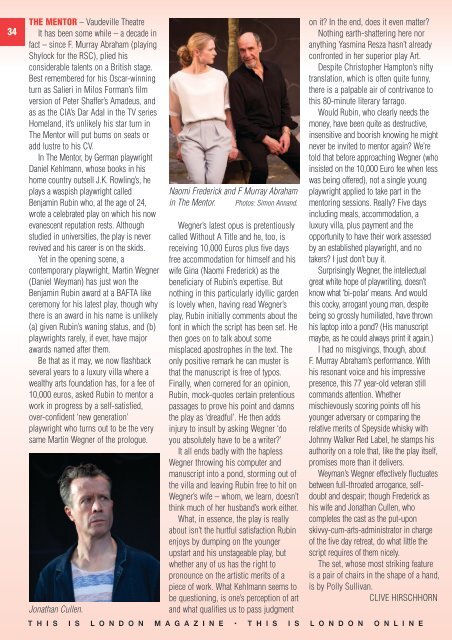

Naomi Frederick and F Murray Abraham<br />

in The Mentor. Photos: Simon Annand.<br />

Wegner’s latest opus is pretentiously<br />

called Without A Title and he, too, is<br />

receiving 10,000 Euros plus five days<br />

free accommodation for himself and his<br />

wife Gina (Naomi Frederick) as the<br />

beneficiary of Rubin’s expertise. But<br />

nothing in this particularly idyllic garden<br />

is lovely when, having read Wegner’s<br />

play, Rubin initially comments about the<br />

font in which the script has been set. He<br />

then goes on to talk about some<br />

misplaced apostrophes in the text. The<br />

only positive remark he can muster is<br />

that the manuscript is free of typos.<br />

Finally, when cornered for an opinion,<br />

Rubin, mock-quotes certain pretentious<br />

passages to prove his point and damns<br />

the play as ‘dreadful’. He then adds<br />

injury to insult by asking Wegner ‘do<br />

you absolutely have to be a writer?’<br />

It all ends badly with the hapless<br />

Wegner throwing his computer and<br />

manuscript into a pond, storming out of<br />

the villa and leaving Rubin free to hit on<br />

Wegner’s wife – whom, we learn, doesn’t<br />

think much of her husband’s work either.<br />

What, in essence, the play is really<br />

about isn’t the hurtful satisfaction Rubin<br />

enjoys by dumping on the younger<br />

upstart and his unstageable play, but<br />

whether any of us has the right to<br />

pronounce on the artistic merits of a<br />

piece of work. What Kehlmann seems to<br />

be questioning, is one’s perception of art<br />

and what qualifies us to pass judgment<br />

on it? In the end, does it even matter?<br />

Nothing earth-shattering here nor<br />

anything Yasmina Resza hasn’t already<br />

confronted in her superior play Art.<br />

Despite Christopher Hampton’s nifty<br />

translation, which is often quite funny,<br />

there is a palpable air of contrivance to<br />

this 80-minute literary farrago.<br />

Would Rubin, who clearly needs the<br />

money, have been quite as destructive,<br />

insensitive and boorish knowing he might<br />

never be invited to mentor again? We’re<br />

told that before approaching Wegner (who<br />

insisted on the 10,000 Euro fee when less<br />

was being offered), not a single young<br />

playwright applied to take part in the<br />

mentoring sessions. Really? Five days<br />

including meals, accommodation, a<br />

luxury villa, plus payment and the<br />

opportunity to have their work assessed<br />

by an established playwright, and no<br />

takers? I just don’t buy it.<br />

Surprisingly Wegner, the intellectual<br />

great white hope of playwriting, doesn’t<br />

know what ‘bi-polar’ means. And would<br />

this cocky, arrogant young man, despite<br />

being so grossly humiliated, have thrown<br />

his laptop into a pond? (His manuscript<br />

maybe, as he could always print it again.)<br />

I had no misgivings, though, about<br />

F. Murray Abraham’s performance. With<br />

his resonant voice and his impressive<br />

presence, this 77 year-old veteran still<br />

commands attention. Whether<br />

mischievously scoring points off his<br />

younger adversary or comparing the<br />

relative merits of Speyside whisky with<br />

Johnny Walker Red Label, he stamps his<br />

authority on a role that, like the play itself,<br />

promises more than it delivers.<br />

Weyman’s Wegner effectively fluctuates<br />

between full-throated arrogance, selfdoubt<br />

and despair; though Frederick as<br />

his wife and Jonathan Cullen, who<br />

completes the cast as the put-upon<br />

skivvy-cum-arts-administrator in charge<br />

of the five day retreat, do what little the<br />

script requires of them nicely.<br />

The set, whose most striking feature<br />

is a pair of chairs in the shape of a hand,<br />

is by Polly Sullivan.<br />

CLIVE HIRSCHHORN<br />

t h i s i s l o n d o n m a g a z i n e • t h i s i s l o n d o n o n l i n e