Podosomes at a Glance - Journal of Cell Science - The Company of ...

Podosomes at a Glance - Journal of Cell Science - The Company of ...

Podosomes at a Glance - Journal of Cell Science - The Company of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong><br />

<strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong> <strong>at</strong> a <strong>Glance</strong> 2079<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> <strong>at</strong> a glance<br />

Stefan Linder* and Petra Kopp<br />

Institut für Prophylaxe und Epidemiologie der<br />

Kreislaufkrankheiten, Ludwig-Maximilians-<br />

Universität, Pettenk<strong>of</strong>erstr. 9, 80336 München,<br />

Germany<br />

*Author for correspondence (e-mail:<br />

stefan.linder@med.uni-muenchen.de)<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong> 118, 2079-2082<br />

Published by <strong>The</strong> <strong>Company</strong> <strong>of</strong> Biologists 2005<br />

doi:10.1242/jcs.02390<br />

<strong>Cell</strong>s can contact the extracellular m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

(ECM) through a variety <strong>of</strong> specialized<br />

structures. <strong>The</strong>se cell-m<strong>at</strong>rix contacts<br />

contain membrane proteins such as<br />

integrins, which bind both m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

components and cellular proteins, thus<br />

bridging the substr<strong>at</strong>um and the<br />

cytoskeleton (reviewed in Adams,<br />

2001). M<strong>at</strong>rix contacts provide the<br />

physical linkage th<strong>at</strong> enables cells to<br />

Overlay Talin F-actin<br />

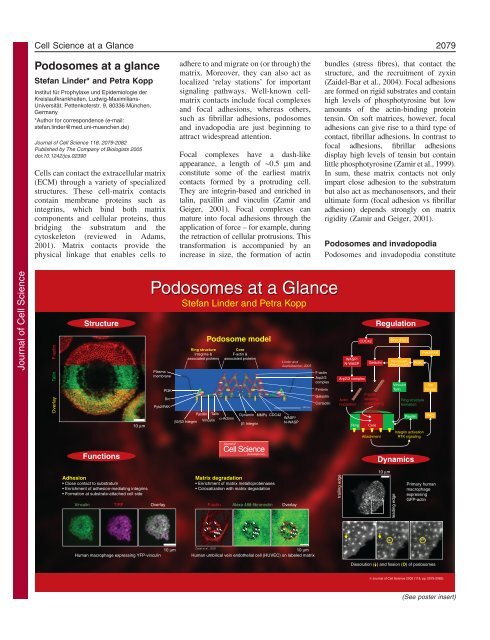

Structure<br />

Functions<br />

10 µm<br />

Adhesion<br />

Close contact to substr<strong>at</strong>um<br />

Enrichment <strong>of</strong> adhesion-medi<strong>at</strong>ing integrins<br />

Form<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>at</strong> substr<strong>at</strong>e-<strong>at</strong>tached cell side<br />

adhere to and migr<strong>at</strong>e on (or through) the<br />

m<strong>at</strong>rix. Moreover, they can also act as<br />

localized ‘relay st<strong>at</strong>ions’ for important<br />

signaling p<strong>at</strong>hways. Well-known cellm<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

contacts include focal complexes<br />

and focal adhesions, whereas others,<br />

such as fibrillar adhesions, podosomes<br />

and invadopodia are just beginning to<br />

<strong>at</strong>tract widespread <strong>at</strong>tention.<br />

Focal complexes have a dash-like<br />

appearance, a length <strong>of</strong> ~0.5 µm and<br />

constitute some <strong>of</strong> the earliest m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

contacts formed by a protruding cell.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y are integrin-based and enriched in<br />

talin, paxillin and vinculin (Zamir and<br />

Geiger, 2001). Focal complexes can<br />

m<strong>at</strong>ure into focal adhesions through the<br />

applic<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> force – for example, during<br />

the retraction <strong>of</strong> cellular protrusions. This<br />

transform<strong>at</strong>ion is accompanied by an<br />

increase in size, the form<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> actin<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> <strong>at</strong> a <strong>Glance</strong><br />

Stefan Linder and Petra Kopp<br />

Plasma<br />

membrane<br />

Vinculin TIRF Overlay<br />

PI3K<br />

Src<br />

10 µm<br />

Human macrophage expressing YFP-vinculin<br />

Ring structure<br />

Integrins &<br />

associ<strong>at</strong>ed proteins<br />

Podosome model<br />

Core<br />

F-actin &<br />

associ<strong>at</strong>ed proteins<br />

Pyk2/FAK<br />

Paxillin Talin<br />

Dynamin MMPs CDC42<br />

WASP/<br />

Vinculin<br />

α-Actinin<br />

β2/β3 Integrin<br />

β1 Integrin<br />

N-WASP<br />

jcs.biologists.org<br />

M<strong>at</strong>rix degrad<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

Enrichment <strong>of</strong> m<strong>at</strong>rix metalloproteinases<br />

Colocaliz<strong>at</strong>ion with m<strong>at</strong>rix degrad<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

F-actin Alexa 488-fibronectin Overlay<br />

Linder and<br />

Aepfelbacher, 2003<br />

F-actin<br />

Arp2/3<br />

complex<br />

Fimbrin<br />

Gelsolin<br />

Cortactin<br />

Osiak et al., 2005<br />

10 µm<br />

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) on labeled m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

bundles (stress fibres), th<strong>at</strong> contact the<br />

structure, and the recruitment <strong>of</strong> zyxin<br />

(Zaidel-Bar et al., 2004). Focal adhesions<br />

are formed on rigid substr<strong>at</strong>es and contain<br />

high levels <strong>of</strong> phosphotyrosine but low<br />

amounts <strong>of</strong> the actin-binding protein<br />

tensin. On s<strong>of</strong>t m<strong>at</strong>rices, however, focal<br />

adhesions can give rise to a third type <strong>of</strong><br />

contact, fibrillar adhesions. In contrast to<br />

focal adhesions, fibrillar adhesions<br />

display high levels <strong>of</strong> tensin but contain<br />

little phosphotyrosine (Zamir et al., 1999).<br />

In sum, these m<strong>at</strong>rix contacts not only<br />

impart close adhesion to the substr<strong>at</strong>um<br />

but also act as mechanosensors, and their<br />

ultim<strong>at</strong>e form (focal adhesion vs fibrillar<br />

adhesion) depends strongly on m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

rigidity (Zamir and Geiger, 2001).<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> and invadopodia<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> and invadopodia constitute<br />

trailing edge<br />

WASP/<br />

N-WASP<br />

Arp2/3 complex<br />

Actin<br />

nucle<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

CDC42<br />

F-actin<br />

severing<br />

+uncapping<br />

Ring Core<br />

Attachment<br />

Regul<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

Gelsolin PI3K<br />

Dynamics<br />

10 µm<br />

Rho (Rac)<br />

PtdIns(3,4)P2 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 Vinculin<br />

Talin<br />

leading edge<br />

Ring structure<br />

form<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

Paxillin<br />

Integrin activ<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

RTK signaling<br />

Pyk2/FAK<br />

Src<br />

kinase<br />

PKC<br />

Primary human<br />

macrophage<br />

expressing<br />

GFP-actin<br />

Dissolution ( ) and fission (O) <strong>of</strong> podosomes<br />

© <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong> 2005 (118, pp. 2079-2082)<br />

(See poster insert)

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong><br />

2080<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong> 118 (10)<br />

two forms <strong>of</strong> dot-like m<strong>at</strong>rix contact th<strong>at</strong><br />

differ from those described above<br />

structurally and functionally (reviewed<br />

in Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003;<br />

Buccione et al., 2004). Structurally, their<br />

most distinguishing fe<strong>at</strong>ure is their twopart<br />

architecture: they have a core <strong>of</strong> Factin<br />

and actin-associ<strong>at</strong>ed proteins th<strong>at</strong> is<br />

surrounded by a ring structure consisting<br />

<strong>of</strong> plaque proteins such as talin or<br />

vinculin. This actin-rich core is not<br />

present in other cell-m<strong>at</strong>rix contacts.<br />

Consequently, actin regul<strong>at</strong>ory p<strong>at</strong>hways<br />

exert a major additional influence on<br />

podosome-type contacts. Functionally,<br />

the ability <strong>of</strong> podosomes and<br />

invadopodia to engage in m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

degrad<strong>at</strong>ion clearly sets them apart from<br />

other cell-m<strong>at</strong>rix contacts.<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> are typically formed in cells<br />

<strong>of</strong> the monocytic lineage, such as<br />

macrophages (Lehto et al., 1982; Linder<br />

et al., 1999), osteoclasts (Marchisio et<br />

al., 1984) or (imm<strong>at</strong>ure) dendritic cells<br />

(Burns et al., 2001). However, they can<br />

also be found or induced in a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

other cell types, including smooth<br />

muscle cells (Gimona et al., 2003) and<br />

endothelial cells (Moreau et al., 2003;<br />

Osiak et al., 2005).<br />

By contrast, invadopodia are found in<br />

fibroblasts transformed with viral<br />

oncogenes encoding protein tyrosine<br />

kinases (Tarone et al., 1985) and in some<br />

malignant cell types (Buccione et al.,<br />

2004). Indeed, the first observ<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong><br />

podosome-type adhesions 25 years ago<br />

described such virally induced<br />

invadopodia (David-Pfeuty and Singer,<br />

1980).<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> and invadopodia differ in<br />

their respective sizes and numbers.<br />

Typically, a cell forms dozens <strong>of</strong><br />

podosomes, but there are only a few<br />

invadopodia per cell. However, wh<strong>at</strong><br />

invadopodia lack in numbers, they make<br />

up for in size: <strong>Podosomes</strong> have a<br />

diameter <strong>of</strong> 0.5-1 µm and a depth <strong>of</strong> 0.2-<br />

0.4 µm, whereas invadopodia can<br />

correspond to an array <strong>of</strong> membrane<br />

invagin<strong>at</strong>ions th<strong>at</strong> have a diameter <strong>of</strong> ~8<br />

µm and also can form root-like<br />

extensions into the m<strong>at</strong>rix th<strong>at</strong> are<br />

several micrometers deep (Buccione et<br />

al., 2004; McNiven et al., 2004).<br />

Despite these differences, basic<br />

similarities between the two structures,<br />

both in composition and architecture, are<br />

apparent. Indeed, it has been proposed<br />

th<strong>at</strong> invadopodia might develop from<br />

podosomal precursors (Linder and<br />

Aepfelbacher, 2003; Buccione et al.,<br />

2004). It is therefore an <strong>at</strong>tractive<br />

specul<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong> podosomes and<br />

invadopodia represent a continuum <strong>of</strong><br />

specialized m<strong>at</strong>rix contacts comparable<br />

to the succession <strong>of</strong> focal complexes,<br />

focal adhesions and fibrillar adhesions<br />

described above.<br />

<strong>The</strong> growing list <strong>of</strong> podosomecontaining<br />

cells may point to a<br />

widespread ability <strong>of</strong> cells to form this<br />

type <strong>of</strong> actin-rich structure. Furthermore,<br />

the fact th<strong>at</strong> podosomes are also formed<br />

on s<strong>of</strong>t substr<strong>at</strong>es, such as endothelial<br />

monolayers (Linder and Aepfelbacher,<br />

2003), adds to the notion th<strong>at</strong> podosomes<br />

are physiological structures th<strong>at</strong> are also<br />

formed in the context <strong>of</strong> tissues.<br />

Functions<br />

<strong>The</strong> main functions <strong>of</strong> podosomes<br />

appear to be adhesion and m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

degrad<strong>at</strong>ion. Moreover, podosomes have<br />

also been implic<strong>at</strong>ed in cell migr<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

and invasion. However, much <strong>of</strong> the<br />

evidence for these functions is still<br />

circumstantial and needs to be rigorously<br />

tested.<br />

It is very possible th<strong>at</strong> podosomes have<br />

a role in adhesion, because they establish<br />

close contact to the substr<strong>at</strong>um, which<br />

can be shown by total internal reflection<br />

(TIRF) microscopy, are enriched in<br />

adhesion-medi<strong>at</strong>ing integrins (Linder<br />

and Aepfelbacher, 2003) and form only<br />

<strong>at</strong> the substr<strong>at</strong>e-<strong>at</strong>tached cell side.<br />

<strong>The</strong> aptly named invadopodia were<br />

defined through their ability to perform<br />

m<strong>at</strong>rix degrad<strong>at</strong>ion (Buccione et al.,<br />

2004; McNiven et al., 2004). For<br />

podosomes, the case has been less clear<br />

cut: podosomes in osteoclasts are<br />

enriched in m<strong>at</strong>rix metalloproteases<br />

(S<strong>at</strong>o et al., 1997; Delaissé et al., 2000),<br />

but it was not shown until recently th<strong>at</strong>,<br />

in various cell systems, podosomes<br />

overlap regions <strong>of</strong> m<strong>at</strong>rix degrad<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

(Burgstaller and Gimona, 2005; Osiak et<br />

al., 2005). It is therefore very possible<br />

th<strong>at</strong> podosomes, like invadopodia, have<br />

an inherent ability to lyse the ECM.<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> may also play an accessory<br />

role in cell migr<strong>at</strong>ion. <strong>The</strong>y might help to<br />

establish localized anchorage, thus<br />

stabilizing sites <strong>of</strong> cell protrusion and<br />

ultim<strong>at</strong>ely enabling productive directional<br />

movement. <strong>The</strong> observ<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong><br />

podosomes are recruited to sites <strong>of</strong> cell<br />

protrusion, especially to the leading edge,<br />

appears to be in line with such a concept.<br />

Podosome-type adhesions are mainly<br />

formed in cells th<strong>at</strong> have to cross tissue<br />

boundaries such as monocytes,<br />

imm<strong>at</strong>ure dendritic cells or some types<br />

<strong>of</strong> cancer cell (invadopodia in this case).<br />

Podosome-localized m<strong>at</strong>rix degrad<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>at</strong> the leading edge may therefore also<br />

confer invasive potential to cells.<br />

Finally, podosomes are a prominent part<br />

<strong>of</strong> the actin cytoskeleton in osteoclasts,<br />

where they form continuous belts <strong>at</strong> the<br />

cell periphery (Pfaff and Jurdic, 1999).<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir probable roles in adhesion and<br />

m<strong>at</strong>rix degrad<strong>at</strong>ion suggest an important<br />

role in bone homeostasis. Moreover, their<br />

fusion was believed to form the boneremodeling<br />

organelle <strong>of</strong> osteoclasts, the<br />

so-called sealing zone, a tightly adherent<br />

structure surrounding the space into<br />

which lytic enzymes and protons are<br />

secreted (Lakkakorpi and Väänänen,<br />

1996). However, recent d<strong>at</strong>a suggest th<strong>at</strong><br />

both types <strong>of</strong> organelle are formed<br />

independently (Saltel et al., 2004).<br />

Furthermore, on mineralized bone, their<br />

physiological substr<strong>at</strong>e, osteoclasts form<br />

only sealing zones, but not podosomes<br />

(Saltel et al., 2004). <strong>The</strong> proposed role<br />

for podosomes – as opposed to sealing<br />

zones – in bone homeostasis is therefore<br />

again open for deb<strong>at</strong>e.<br />

Structure and components<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> comprise a core <strong>of</strong> F-actin<br />

and actin-associ<strong>at</strong>ed proteins embedded<br />

in a ring structure <strong>of</strong> integrins and<br />

integrin-associ<strong>at</strong>ed proteins (see poster,<br />

middle and right). Ring and core are<br />

probably linked by bridging molecules<br />

such as α-actinin, and the whole structure<br />

is surrounded by a cloud <strong>of</strong> mostly<br />

monomeric actin molecules (Destaing et<br />

al., 2003). Many podosome components<br />

show a distinct localiz<strong>at</strong>ion to either the<br />

core or ring structure. Typical core<br />

components are F-actin, actin regul<strong>at</strong>ors<br />

such as members <strong>of</strong> the Wiskott-Aldrich<br />

Syndrome protein (WASP) family, the

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong><br />

<strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong> <strong>at</strong> a <strong>Glance</strong> 2081<br />

Arp2/3 complex, gelsolin and cortactin,<br />

whereas adhesion medi<strong>at</strong>ors such as<br />

paxillin, vinculin or talin, and kinases<br />

such as PI3K or Pyk2/FAK preferentially<br />

associ<strong>at</strong>e with the ring structure (Linder<br />

and Aepfelbacher, 2003; Buccione et al.,<br />

2004).<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> are anchored in the<br />

extracellular m<strong>at</strong>rix through integrins.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se are distributed over the whole<br />

outer surface <strong>of</strong> the podosome, but show<br />

an isotype-specific localiz<strong>at</strong>ion: β1<br />

integrins localize mostly to the core,<br />

whereas β2 and β3 integrins localize to<br />

the ring.<br />

Regul<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> are influenced by a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

cellular signaling p<strong>at</strong>hways. Major<br />

modes <strong>of</strong> podosome regul<strong>at</strong>ion include<br />

signaling by Rho family GTPases, actin<br />

regul<strong>at</strong>ory p<strong>at</strong>hways, protein tyrosine<br />

phosphoryl<strong>at</strong>ion, and the influence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

microtubule system.<br />

Rho GTPases<br />

<strong>The</strong> RhoGTPases RhoA, Rac1 and<br />

CDC42 have all been shown to regul<strong>at</strong>e<br />

podosome turnover in various cell types.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir influence on podosomes is<br />

undisputed; however, their particular<br />

mode <strong>of</strong> action may depend on the cell<br />

type. For example, both dominant active<br />

and inactive mutants <strong>of</strong> these GTPases<br />

can interfere with podosome form<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

or localiz<strong>at</strong>ion in dendritic cells (Burns<br />

et al., 2001), while expression <strong>of</strong><br />

dominant active CDC42 leads to<br />

podosome form<strong>at</strong>ion in aortic<br />

endothelial cells (Moreau et al., 2003).<br />

In any case, podosome turnover appears<br />

to need subcellular fine tuning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

GTP/GDP cycles <strong>of</strong> these cellular master<br />

switches (Linder and Aepfelbacher,<br />

2003). Accordingly, active Rho has been<br />

localized to invadopodia in transformed<br />

fibroblasts (Berdeaux et al., 2004).<br />

Actin regul<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>The</strong> most prominent fe<strong>at</strong>ure <strong>of</strong><br />

podosomes is their F-actin-rich core,<br />

which is also necessary for the stability<br />

<strong>of</strong> the whole structure (Lehto et al.,<br />

1982). Members <strong>of</strong> the WASP family, as<br />

well as actin-nucle<strong>at</strong>ing Arp2/3 complex<br />

are both strongly enriched in the<br />

podosome core. Absence <strong>of</strong> these<br />

components, either induced artificially<br />

(Linder et al., 2000a) or in disease<br />

(Linder et al., 1999; Burns et al., 2001)<br />

(reviewed in Calle et al., 2004), results<br />

in disruption <strong>of</strong> podosomes. Another<br />

prominent podosome component<br />

involved in actin regul<strong>at</strong>ion is gelsolin. It<br />

probably contributes to actin turnover<br />

through its ability to both sever and cap<br />

actin filaments (Chellaiah et al., 1998).<br />

Tyrosine phosphoryl<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

It was noted early on th<strong>at</strong> podosome-type<br />

adhesions can be induced by<br />

transform<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> cells with viruses<br />

whose oncogenes encode tyrosine<br />

kinases such as v-Src (Tarone et al.,<br />

1985; Marchisio et al., 1987). Indeed,<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the best ways to visualize<br />

podosomes is by staining phosphoryl<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

tyrosine (Linder and Apfelbacher, 2003),<br />

which is highly enriched in some types <strong>of</strong><br />

adhesive structure. Not surprisingly,<br />

cellular tyrosine kinases such as Src and<br />

Csk play major roles in podosome<br />

regul<strong>at</strong>ion (Howell and Cooper, 1994),<br />

and tools for podosome manipul<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

include Src kinase inhibitors, which<br />

disrupt podosomes (Linder et al., 2000b),<br />

and vanad<strong>at</strong>e, a phosphotyrosine<br />

phosph<strong>at</strong>ase inhibitor, which is able to<br />

induce podosome form<strong>at</strong>ion (Marchisio<br />

et al., 1988).<br />

Microtubules<br />

Microtubules are closely associ<strong>at</strong>ed with<br />

podosomes. Moreover, they have been<br />

shown to stabilize podosome p<strong>at</strong>terns<br />

such as the marginal belts in osteoclasts<br />

(Babb et al., 1997), to influence the<br />

fusion and fission r<strong>at</strong>es <strong>of</strong> podosome<br />

precursors in murine macrophages<br />

(Evans et al., 2003) and to regul<strong>at</strong>e<br />

podosome form<strong>at</strong>ion in human<br />

macrophages (Linder et al., 2000b).<br />

A model for podosome form<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> podosome-inducing p<strong>at</strong>hways<br />

has been performed in a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

cell types. From these d<strong>at</strong>a we can<br />

propose the following simplified model<br />

for podosome form<strong>at</strong>ion: <strong>The</strong> key signal<br />

for initi<strong>at</strong>ion is <strong>at</strong>tachment <strong>of</strong> the cell to<br />

the substr<strong>at</strong>e, because podosomes are<br />

only observed in adherent cells. This<br />

leads to clustering and activ<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong><br />

integrins and signaling by receptor<br />

tyrosine kinases. One <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

upstream signals is probably PKC<br />

activity. This is underscored by the fact<br />

th<strong>at</strong> podosome form<strong>at</strong>ion can be induced<br />

by PKC-activ<strong>at</strong>ing agents, such as<br />

phorbol esters (Gimona et al., 2003).<br />

An important subsequent switch is<br />

activ<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Src. Downstream, a variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> p<strong>at</strong>hways are initi<strong>at</strong>ed, most notably<br />

PI3K signaling (Chellaiah et al., 1998),<br />

which leads to the form<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

phosph<strong>at</strong>idylinositols PtdIns(3,4)P2 and<br />

PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, and activ<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> focal<br />

adhesion kinase (FAK) or its<br />

haem<strong>at</strong>opoietic rel<strong>at</strong>ive Pyk2. 3�<br />

phosphoinositide signaling is also<br />

influenced by the RhoGTPases Rho and<br />

(probably) Rac (Chellaiah et al., 2001;<br />

Sechi and Wehland, 2000).<br />

CDC42, another RhoGTPase, is crucial<br />

for the local initi<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> actin filament<br />

form<strong>at</strong>ion, which gives rise to the<br />

form<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the actin-rich core<br />

structure. This is achieved by releasing<br />

the autoinhibition <strong>of</strong> N-WASP or its<br />

rel<strong>at</strong>ive WASP, which in turn activ<strong>at</strong>es<br />

actin-nucle<strong>at</strong>ing Arp2/3 complex<br />

(Linder et al., 1999; Linder et al., 2000a;<br />

Burns et al., 2001). Turnover <strong>of</strong> corelocalized<br />

actin filaments is probably<br />

facilit<strong>at</strong>ed by gelsolin (Chellaiah et al.,<br />

1998) and the GTPase dynamin<br />

(McNiven et al., 2004; Buccione et al.,<br />

2004). Additionally, dynamin may also<br />

play a role in podosome-localized m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

degrad<strong>at</strong>ion by facilit<strong>at</strong>ing m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

metalloprotease release.<br />

It is unclear how core- and ringform<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

are coordin<strong>at</strong>ed. However,<br />

similarly to core molecules, central<br />

components <strong>of</strong> the ring structure, such as<br />

talin and vinculin, are also influenced by<br />

phosphoinositides (Sechi and Wehland,<br />

2000), and activ<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> paxillin through<br />

integrin-rel<strong>at</strong>ed signaling (Pfaff and<br />

Jurdic, 2001) may constitute one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

earliest signals in ring form<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

Dynamics<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> are highly dynamic<br />

organelles with a half-life <strong>of</strong> 2-12<br />

minutes. Moreover, their inner dynamic<br />

is even faster: F-actin in the core turnes<br />

over 2-3 times during the life span <strong>of</strong> a<br />

podosome (Destaing et al., 2003).<br />

Individual podosomes are motile within

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong><br />

2082<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong> 118 (10)<br />

a certain radius, but movement <strong>of</strong> larger<br />

podosome groups is achieved through<br />

assembly <strong>at</strong> the front and disassembly <strong>at</strong><br />

the rear. This is especially visible in<br />

migr<strong>at</strong>ory cells where podosomes are<br />

recruited to the leading edge.<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> can assemble de novo or by<br />

branching <strong>of</strong>f precursor clusters, which<br />

undergo constant fusion and fission<br />

(Evans et al., 2003) (see poster, lower<br />

right). ‘Regular’ podosomes are mostly<br />

found in the inner regions <strong>of</strong> the cell,<br />

while the larger precursor clusters<br />

localize to the cell periphery or the<br />

leading lamella <strong>of</strong> migr<strong>at</strong>ing cells.<br />

Disease<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong> are assembled from<br />

molecules th<strong>at</strong> have multiple functions<br />

in the cell, such as actin and Src kinases.<br />

Inhibitors <strong>of</strong> podosome assembly<br />

therefore also have pr<strong>of</strong>ound effects<br />

on other parts <strong>of</strong> the cytoskeleton.<br />

Similarly, the absence <strong>of</strong> podosomes in<br />

diseases based on defects in a podosome<br />

component(s) may only constitute a side<br />

effect. <strong>The</strong> podosome aficionado should<br />

therefore take care to ascertain whether<br />

a lack <strong>of</strong> podosomes causes or is simply<br />

symptom<strong>at</strong>ic <strong>of</strong> a particular phenotype.<br />

Podosome-associ<strong>at</strong>ed diseases include<br />

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome (WAS) and<br />

chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).<br />

WAS-p<strong>at</strong>ient macrophages (Linder et<br />

al., 1999) and dendritic cells from CML<br />

p<strong>at</strong>ients (Dong et al., 2003) both display<br />

pronounced defects in podosome<br />

form<strong>at</strong>ion and chemotaxis.<br />

We thank Bettina Ebbing for help with TIRF<br />

microscopy, Alexander Bershadsky for the gift <strong>of</strong><br />

YFP-vinculin, Peter C. Weber and Jürgen<br />

Heesemann for continuous support and Barbara<br />

Böhlig for expert technical assistance. Work from<br />

our lab is supported by the Deutsche<br />

Forschungsgemeinschaft (GRK 438, SFB 413), the<br />

Friedrich Baur Stiftung and the August Lenz<br />

Stiftung. We apologize to all whose work was not<br />

mentioned owing to space limit<strong>at</strong>ions.<br />

References<br />

Adams, J. C. (2001). <strong>Cell</strong>-m<strong>at</strong>rix contact structures.<br />

<strong>Cell</strong>. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 371-392.<br />

Babb, S. G., M<strong>at</strong>sudaira, P., S<strong>at</strong>o, M., Correia, I.<br />

and Lim, S. S. (1997). Fimbrin in podosomes <strong>of</strong><br />

monocyte-derived osteoclasts. <strong>Cell</strong> Motil.<br />

Cytoskeleton 37, 308-325.<br />

Berdeaux, R. L., Diaz, B., Kim, L. and Martin, G.<br />

S. (2004). Active Rho is localized to podosomes<br />

induced by oncogenic Src and is required for their<br />

assembly and function. J. <strong>Cell</strong> Biol. 166, 317-323.<br />

Buccione, R., Orth, J. D. and McNiven, M. A.<br />

(2004). Foot and mouth: podosomes, invadopodia and<br />

circular dorsal ruffles. N<strong>at</strong>. Rev. Mol.<strong>Cell</strong> Biol. 5, 647-<br />

657.<br />

Burgstaller, G. and Gimona, M. (2005). Podosomemedi<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

m<strong>at</strong>rix resorption and cell motility in<br />

vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart<br />

Circ. Physiol. (epub Feb. 4)<br />

Burns, S., Thrasher, A. J., Blundell, M. P.,<br />

Machesky, L. and Jones, G. E. (2001). Configur<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>of</strong> human dendritic cell cytoskeleton by Rho GTPases,<br />

the WAS protein, and differenti<strong>at</strong>ion. Blood 98, 1142-<br />

1149.<br />

Calle, Y., Chou, H. C., Thrasher, A. J. and Jones,<br />

G. E. (2004). Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein and<br />

the cytoskeletal dynamics <strong>of</strong> dendritic cells. J. P<strong>at</strong>hol.<br />

204, 460-469.<br />

Chellaiah, M., Fitzgerald, C., Alvarez, U. and<br />

Hruska, K. (1998). c-Src is required for stimul<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>of</strong> gelsolin-associ<strong>at</strong>ed phosph<strong>at</strong>idylinositol 3-kinase.<br />

J. Biol. Chem. 273, 11908-11916.<br />

Chellaiah, M. A., Biswas, R. S., Yuen, D., Alvarez,<br />

U. M. and Hruska, K. A. (2001).<br />

Phosph<strong>at</strong>idylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosph<strong>at</strong>e directs<br />

associ<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Src homology 2-containing signaling<br />

proteins with gelsolin. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47434-<br />

47444.<br />

David-Pfeuty, T. and Singer, S. J. (1980). Altered<br />

distributions <strong>of</strong> the cytoskeletal proteins vinculin and<br />

alpha-actinin in cultured fibroblasts transformed by<br />

Rous sarcoma virus. Proc. N<strong>at</strong>l. Acad. Sci. USA 77,<br />

6687-6691.<br />

Delaissé, J. M., Engsig, M. T., Everts, V., del<br />

Carmen Ovejero, M., Ferreras, M., Lund, L., Vu,<br />

T. H., Werb, Z., Winding, B., Lochter, A. et al.<br />

(2000). Proteinases in bone resorption: obvious and<br />

less obvious roles. Clin. Chim. Acta 291, 223-234.<br />

Destaing, O., Saltel, F., Geminard, J. C., Jurdic, P.<br />

and Bard, F. (2003). <strong>Podosomes</strong> display actin<br />

turnover and dynamic self-organiz<strong>at</strong>ion in osteoclasts<br />

expressing actin-green fluorescent protein. Mol. Biol.<br />

<strong>Cell</strong> 14, 407-416.<br />

Dong, R., Cwynarski, K., Entwistle, A., Marelli-<br />

Berg, F., Dazzi, F., Simpson, E., Goldman, J. M.,<br />

Melo, J. V., Lechler, R. I., Bellantuono, I. et al.<br />

(2003). Dendritic cells from CML p<strong>at</strong>ients have<br />

altered actin organiz<strong>at</strong>ion, reduced antigen processing,<br />

and impaired migr<strong>at</strong>ion. Blood 101, 3560-3567.<br />

Evans, J.G., Correia, I., Krasavina, O., W<strong>at</strong>son, N.<br />

and M<strong>at</strong>sudaira, P. (2003). Macrophage podosomes<br />

assemble <strong>at</strong> the leading lamella by growth and<br />

fragment<strong>at</strong>ion. J. <strong>Cell</strong> Biol. 161, 697-705.<br />

Gimona, M., Kaverina, I., Resch, G. P., Vignal, E.<br />

and Burgstaller, G. (2003). Calponin repe<strong>at</strong>s regul<strong>at</strong>e<br />

actin filament stability and form<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> podosomes in<br />

smooth muscle cells. Mol. Biol. <strong>Cell</strong> 14, 2482-2491.<br />

Howell, B. W. and Cooper, J. A. (1994). Csk<br />

suppression <strong>of</strong> Src involves movement <strong>of</strong> Csk to sites<br />

<strong>of</strong> Src activity. Mol. <strong>Cell</strong> Biol. 14, 5402-5411.<br />

Lakkakorpi, P. T. and Väänänen, H. K. (1996).<br />

Cytoskeletal changes in osteoclasts during the<br />

resorption cycle. Microsc. Res. Tech. 33, 171-181.<br />

Lehto, V. P., Hovi, T., Vartio, T., Badley, R. A. and<br />

Virtanen, I. (1982). Reorganiz<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> cytoskeletal<br />

and contractile elements during transition <strong>of</strong> human<br />

monocytes into adherent macrophages. Lab. Invest.<br />

47, 391-399.<br />

Linder, S. and Aepfelbacher, M. (2003).<br />

<strong>Podosomes</strong>: adhesion hot-spots <strong>of</strong> invasive cells.<br />

Trends <strong>Cell</strong> Biol. 13, 376-385.<br />

Linder, S., Nelson, D., Weiss, M. and Aepfelbacher,<br />

M. (1999). Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein<br />

regul<strong>at</strong>es podosomes in primary human macrophages.<br />

Proc. N<strong>at</strong>l. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9648-9653.<br />

Linder, S., Higgs, H., Hufner, K., Schwarz, K.,<br />

Pannicke, U. and Aepfelbacher, M. (2000a). <strong>The</strong><br />

polariz<strong>at</strong>ion defect <strong>of</strong> Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome<br />

macrophages is linked to dislocaliz<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the Arp2/3<br />

complex. J. Immunol. 165, 221-225.<br />

Linder, S., Hufner, K., Wintergerst, U. and<br />

Aepfelbacher, M. (2000b). Microtubule-dependent<br />

form<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> podosomal adhesion structures in<br />

primary human macrophages. J. <strong>Cell</strong> Sci. 113, 4165-<br />

4176.<br />

Marchisio, P. C., Cirillo, D., Naldini, L.,<br />

Primavera, M. V., Teti, A. and Zambonin-Zallone,<br />

A. (1984). <strong>Cell</strong>-substr<strong>at</strong>um interaction <strong>of</strong> cultured<br />

avian osteoclasts is medi<strong>at</strong>ed by specific adhesion<br />

structures. J. <strong>Cell</strong> Biol. 99, 1696-1705.<br />

Marchisio, P. C., Cirillo, D., Teti, A., Zambonin-<br />

Zallone, A. and Tarone, G. (1987). Rous sarcoma<br />

virus-transformed fibroblasts and cells <strong>of</strong> monocytic<br />

origin display a peculiar dot-like organiz<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong><br />

cytoskeletal proteins involved in micr<strong>of</strong>ilamentmembrane<br />

interactions. Exp. <strong>Cell</strong> Res. 169, 202-214.<br />

Marchisio, P. C., D’Urso, N., Comoglio, P. M.,<br />

Giancotti, F. G. and Tarone, G. (1988). Vanad<strong>at</strong>etre<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

baby hamster kidney fibroblasts show<br />

cytoskeleton and adhesion p<strong>at</strong>terns similar to their<br />

Rous sarcoma virus-transformed counterparts. J. <strong>Cell</strong><br />

Biochem. 37, 151-159.<br />

McNiven, M. A., Baldassarre, M. and Buccione, R.<br />

(2004). <strong>The</strong> role <strong>of</strong> dynamin in the assembly and<br />

function <strong>of</strong> podosomes and invadopodia. Front.<br />

Biosci. 9, 1944-1953.<br />

Moreau, V., T<strong>at</strong>in, F., Varon, C. and Genot, E.<br />

(2003). Actin can reorganize into podosomes in aortic<br />

endothelial cells, a process controlled by Cdc42 and<br />

RhoA. Mol. <strong>Cell</strong> Biol. 23, 6809-6822.<br />

Osiak, A.-E., Zenner, G. and Linder, S. (2005).<br />

Subconfluent endothelial cells form podosomes<br />

downstream <strong>of</strong> cytokine and RhoGTPase signaling.<br />

Exp. <strong>Cell</strong> Res., in press<br />

Pfaff, M. and Jurdic, P. (2001). <strong>Podosomes</strong> in<br />

osteoclast-like cells: structural analysis and<br />

cooper<strong>at</strong>ive roles <strong>of</strong> paxillin, proline-rich tyrosine<br />

kinase 2 (Pyk2) and integrin alphaVbeta3. J. <strong>Cell</strong> Sci.<br />

114, 2775-2786.<br />

Saltel, F., Destaing, O., Bard, F., Eichert, D. and<br />

Jurdic, P. (2004). Ap<strong>at</strong>ite-medi<strong>at</strong>ed actin dynamics in<br />

resorbing osteoclasts. Mol. Biol. <strong>Cell</strong> 15, 5231-5241.<br />

S<strong>at</strong>o, T., del Carmen Ovejero, M., Hou, P.,<br />

Heegaard, A. M., Kumegawa, M., Foged, N. T. and<br />

Delaisse, J. M. (1997). Identific<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

membrane-type m<strong>at</strong>rix metalloproteinase MT1-MMP<br />

in osteoclasts. J. <strong>Cell</strong> Sci. 110, 589-596.<br />

Sechi, A. S. and Wehland, J. (2000). <strong>The</strong> actin<br />

cytoskeleton and plasma membrane connection:<br />

PtdIns(4,5)P(2) influences cytoskeletal protein activity<br />

<strong>at</strong> the plasma membrane. J. <strong>Cell</strong> Sci. 113, 3685-3695.<br />

Tarone, G., Cirillo, D., Giancotti, F. G., Comoglio,<br />

P. M. and Marchisio, P. C. (1985). Rous sarcoma<br />

virus-transformed fibroblasts adhere primarily <strong>at</strong><br />

discrete protrusions <strong>of</strong> the ventral membrane called<br />

podosomes. Exp. <strong>Cell</strong> Res. 159, 141-157.<br />

Zaidel-Bar, R., Cohen, M., Addadi, L. and Geiger,<br />

B. (2004). Hierarchical assembly <strong>of</strong> cell-m<strong>at</strong>rix<br />

adhesion complexes Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32, 416-<br />

420.<br />

Zamir, E. and Geiger, B. (2001). Molecular<br />

complexity and dynamics <strong>of</strong> cell-m<strong>at</strong>rix adhesions. J.<br />

<strong>Cell</strong> Sci. 114, 3583-3590.<br />

Zamir, E., K<strong>at</strong>z, B. Z., Aota, S., Yamada, K. M.,<br />

Geiger, B. and Kam, Z. (1999). Molecular diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> cell-m<strong>at</strong>rix adhesions. J. <strong>Cell</strong> Sci. 112, 1655-1669.<br />

<strong>Cell</strong> <strong>Science</strong> <strong>at</strong> a <strong>Glance</strong> on the Web<br />

Electronic copies <strong>of</strong> the poster insert are<br />

available in the online version <strong>of</strong> this article<br />

<strong>at</strong> jcs.biologists.org. <strong>The</strong> JPEG images can<br />

be downloaded for printing or used as<br />

slides.