BraenBook-TemplatePages

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Braen: A History Built on Stone<br />

The Story of The Braen Family of Companies<br />

AUTHOR NAME HERE

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

I<br />

1

Braen: A History Built on Stone<br />

The Story of The Braen Family of Companies<br />

AUTHOR NAME HERE

This book is dedicated to all of the employees,<br />

clients and friends who have made it possible to<br />

write a truly unique history.<br />

COPYWRITE LEGAL, ETC. Ipsant vent quam et que<br />

vellaut quiania sectat laboreic tem custiuntorum<br />

latemquid essitis molore veliquae raernam nonseque<br />

sunt quam, sum et re vendandebis in et voluptaepe<br />

dolupit quis eturiatus moluptat volorepe dolent audam<br />

aborest, conemquod eos millaud itiatendem et<br />

estem reri odis eate evelicab inctur sitae vento dollis<br />

aut fugit faccum vidi digent.<br />

Im aborro blaborrundi sit inimilis nimosanis am<br />

fuga. Itatem lias asperitae nonsed quam ulparcid<br />

4 SECTION TITLE

CONTENTS<br />

Prelude<br />

xx<br />

From Breen to Braen x x<br />

Samuel Braen, Road Builder<br />

xx<br />

Samuel Braen’s Sons x x<br />

Stone Industries<br />

xx<br />

Postscript<br />

xx

This, then, is the story of how five generations of<br />

Braens played a significant part in Northern New Jersey’s<br />

dramatic transformation from a rural place...<br />

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat. Pis et facerit eos resciae eos reribus, sum sit labo. Bus.Pid mi, ommod milique odiscim<br />

agnatem rem latur sequam sitas res sit et mod ut et enihictatur, que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

6 SECTION TITLE

Preface<br />

Braen, with an outsized A in the middle, has been a part of the North Jersey landscape for decades—at<br />

quarry entrances, on trucks, and more recently on a supply store. Today, more than two hundred people—<br />

clerks, drivers, mechanics, managers, and operators—work at these facilities alongside six people who<br />

actually carry that name: the current group of owners--the fifth generation of Braens in the stone business.<br />

Fifty years ago, upwards of 2000 people worked under that name at dozens of places during the peak of<br />

the construction season. Besides quarries and batch plants, there were construction sites for roads, military<br />

installations, water treatment plants, shopping centers, and industrial parks, both in New Jersey and<br />

New York, and for a time even as far away as Bermuda. During those years the Braen logo included the<br />

owner’s first name, “Sam.” Hundreds of trucks painted dark green, gray, and red made the Sam Braen<br />

logo a part of everyday life for anyone touring the region. During the 1950s and 1960s the Sam Braen<br />

companies built a sizable part of modern Bergen County.<br />

Fifty years before that, another Samuel Braen toiled with his sons, John and Abram, in a secluded quarry<br />

near the Great Falls of the Passaic River, a place called the Valley of the Rocks. Manufacturing stone complemented<br />

Sam’s road building business. They used hammers to drive drill bits into the rock, and learned<br />

the art of blasting the hard way, by trial and error. That was the place where Braen and stone became<br />

firmly fused.<br />

Fifty years before that, Sam’s grandfather arrived in the United States. Aart Breen hoped his sons could be<br />

independent people, earning a good living under better conditions than the ones prevailing in the village of<br />

Ouddorp, on the far edge of the poorest region in the Kingdom of the Netherlands. He also believed that<br />

God-given skills were not just for personal use. Success meant more than money.<br />

That any family could own a business for five generations is truly remarkable, a milestone rarely reached,<br />

as rare as snow in July. Since 1904, Braen and stone have stood together because Aart’s descendants<br />

remembered the truth he carried with him when he crossed the ocean in 1851: the greater reward is in the<br />

serving, not in the selling. They like to say that the quarry got in their blood. And it has stayed there for<br />

115 years. For the family, their employees, and their customers, living by Aart’s adage meant going to work<br />

and doing business by the rules. That made each day’s work worthwhile for everyone.<br />

This, then, is the story of how five generations of Braens played a significant part in Northern New Jersey’s<br />

dramatic transformation from a rural place, first to a collection of industrial cities and then to suburban<br />

subdivisions. Through building booms, depression, world wars and a cold war this family touched the lives<br />

of not just their employees and customers, but the communities they helped build.<br />

SECTION NUMBER 7

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat. Pis et facerit<br />

eos resciae eos reribus, sum sit labo.<br />

Bus.Pid mi, ommod milique odiscim agnatem<br />

rem latur sequam sitas res sit et mod<br />

ut et enihictatur, que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

8 SECTION TITLE

From Breen to Braen<br />

On April 30, 1851, the three-masted bark Australie, a few weeks out of Rotterdam eased into a lower<br />

Manhattan slip with one hundred passengers aboard. Since it was a Dutch owned ship, a Dutch-speaking<br />

minister stood at the foot of the gangplank to escort the newcomers first to Castle Garden and then to the<br />

boats that would lead them toward their American destinations.<br />

Aart and Cornelia Breen were two of the older passengers, he fifty and she one year older. Six children<br />

trailed behind them, the oldest twenty-three, and the youngest only five. Three more of Aart and Cornelia’s<br />

children lay buried in a cemetery in the tiny village of Ouddorp in the southwestern corner of The Netherlands.<br />

Their oldest child, a daughter, lived with her in-laws on a farm in Wayne Township, New Jersey, not<br />

that the place name meant much to Aart. Aart and Cornelia also knew that another acquaintance, a man<br />

who had recently finished his apprenticeship in Aart’s shoemaking shop in Ouddorp, also lived near their<br />

daughter Maria. He lived in a group of houses built near the Passaic River’s head of navigation. Two years<br />

before, when Maria had left the Netherlands with her husband and infant son, she boarded the ship a wife<br />

and arrived in New York a widow, with her husband buried at sea. Aart and Cornelia had been spared the<br />

sight of a dreaded mid-ocean committal service on their voyage to America.<br />

They came from Ouddorp, a village on an island to the south of Rotterdam. With a shallow harbor, and<br />

a population numbering in the hundreds, it had never been a thriving place. Isolation bred a traditional<br />

society marked by religious fervor. Since the Reformation, Ouddorp supported two congregations, the state<br />

church and a Mennonite group. Until the 1830s two crops sustained the local economy: chicory (a sweetener)<br />

and madder (a root that produced red dyes). When synthetic substitutes rendered them obsolete, the<br />

local economy collapsed. Many saw the hand of divine judgment behind the severe downturn. By 1845<br />

almost half of the households in Ouddorp and the neighboring municipalities on the island survived with<br />

government assistance. It was literally the poorest place in the entire kingdom. And so an exodus began,<br />

first to a new settlement in the Netherlands, and then to the United States.<br />

This was the life in which Aart and Cornelia attempted to raise their sizeable family. He made shoes in a<br />

shop located at the front of his house near the center of town. Getting paid for his services often meant<br />

bartering since cash was very scarce. The prospects for the four Breen sons became bleaker by the year.<br />

They could cadge a few coins as farm laborers, but those wages would never support a family. Ouddorp af-<br />

SECTION NUMBER 9

Photo Credit<br />

Aart and Cornelia had never before seen anything like Paterson.<br />

The seventy foot high falls that powered the cotton looms and locomotive<br />

shop lathes were unlike any natural feature in the Netherlands.<br />

forded only the chance to be a tenant on a glorified garden plot, one hardly likely to produce enough vegetables<br />

for a year. Unless something changed, Aart’s sons would be condemned to being the lowest of the low<br />

in the village, landless laborers. As for daughters, they could offer precious little as a dowry to any suitors.<br />

There were preachers in the Netherlands whose sermons often ended with a call for the faithful to flee<br />

the coming destruction. And there were other preachers, from the Dutch Reformed church in the Hudson<br />

Valley, who believed the United States could use an infusion of the virtues Dutch Calvinists would bring<br />

as immigrants: honesty, thrift, tenacity, fortitude, piety. The American ministers assured the Dutch ministers<br />

that immigrants would be cared for on arrival in New York: fed, housed, and ticketed to their final<br />

destinations. The Dutch ministers wanted the immigrants to settle in separate communities, to maintain<br />

their virtuosity. In 1846 and 1847 two of those ministers founded settlements in Iowa and Michigan. The<br />

American ministers hoped the newcomers would be a leaven in the broader American society. In the end,<br />

both sides won.<br />

Reaching the west required money for boat fares: up the Hudson to Albany, along the Erie Canal to Buffalo,<br />

and then on a steamer to Michigan or Chicago. The folks who opted for Iowa bypassed all this by sailing<br />

10 SECTION TITLE

to New Orleans, steaming north on the Mississippi to Keokuk, changing to a smaller boat to scale the Des<br />

Moines River, before walking the final miles to place called Pella. The first of the Ouddorp exiles lacked the<br />

means to travel beyond New York. Their voyage to America ended on the banks of the Passaic River, or just<br />

over the First Watchung Mountain in Wayne Township. They settled among the descendants of Dutch colonists<br />

who had arrived before the American Revolution. So isolated were they, that a century and half later<br />

many of them still spoke an old form of the Dutch language, both at home and in church. For the Ouddorp<br />

immigrants, that was good enough. Numbered among them: Aart Breen’s sister, Krientje (Catherine), and<br />

her husband, Jacob Tanis. Then Aart arrived, followed by two of his brothers. By 1860 there were a dozen<br />

Breen households in the Paterson area.<br />

Aart and Cornelia had never before seen anything like Paterson. The seventy foot high falls that powered<br />

the cotton looms and locomotive shop lathes were unlike any natural feature in the Netherlands. And the<br />

rocky hills towering to the West of the city were a stark change from the shifting sand dunes by Ouddorp.<br />

In 1851, only one road climbed over that first ridge of the Appalachians. Hamburgh Turnpike had been<br />

chartered and built soon after the first mills appeared by the Falls in 1793. It was the only way that Aart<br />

and Cornelia could reach their daughter’s home in Wayne. Whenever they made that trip, they passed the<br />

place where one day a sign with their Americanized surname would stand, near the crest of the hill.<br />

Aart’s relatives and neighbors from Ouddorp had no problem understanding him when he spoke. They<br />

knew that a Dutch double ‘e’ made a long ‘a’ sound. To Aart’s English speaking acquaintances that remained<br />

a problem. And so, when he pronounced his name the correct (Dutch) way, they wrote it in English<br />

ways: Brain, or Brane, or Braine, or Braen (phonetically the least ‘correct’ English spelling!). They also had<br />

trouble with his first name. He would be called Abraham, or Abram, or Aron, but, until the 1870s, almost<br />

never Aart. He lived his life among those who did understand him, in an enclave near the place where the<br />

Hamburgh Turnpike crossed the Passaic River and intersected with the Goffle Road, within eyesight of a<br />

steep, rocky patch the locals called the Valley of the Rocks.<br />

Paterson’s First Ward housed the city’s largest Dutch immigrant neighborhood. In it Aart lived and worked<br />

at his trade. For several years he worshipped at the Second Reformed Church, with its services in English,<br />

until the immigrants organized their own congregation, First Holland Reformed Church two blocks away on<br />

North First St. He did well enough, soon enough, to convince his brothers, Paul and Martin, to bring their<br />

families to Paterson in 1853. As for his four sons, they all became independent people, as either artisans<br />

or farmers. Two of them joined their sister in Iowa, while two remained in New Jersey. John, the oldest, put<br />

his hand to the plow on a farmstead he bought a few miles up Goffle Road, on the border between Passaic<br />

and Bergen counties.<br />

The 1860s were a time of great upheaval and great growth for the Paterson area. The Civil War sent thousands<br />

into Union army regiments. The city’s textile industry, gun factories, and locomotive shops produced<br />

the uniforms, weapons, and transportation that led to victory in 1865. For people like Aart Breen, the war<br />

meant work producing shoes for both soldiers and factory workers. For farmers, like John Breen (who was<br />

too old to be drafted), it meant high prices for all the products that fed those soldiers and factory workers.<br />

One enterprising Dutch immigrant from Aart’s neighborhood, Abraham Vermeulen, a tailor turned undertaker<br />

and realtor, invested in a stone quarry along Goffle Road, presumably to produce railroad ballast,<br />

curbstones, and materials for macadamized roads. In any event, money poured into Paterson, encouraging<br />

investment in more mills, swelling the population, and stimulating both agriculture and the construction<br />

trades in the area.<br />

SECTION NUMBER 11

This was the world of possibilities Simon Breen inherited as he grew in John<br />

Breen’s household. John’s wife, Maatje Verhoeve Van Heest, was another immigrant<br />

from Ouddorp. She arrived in New Jersey in 1852 at the age of nineteen,<br />

one of ten children in Simon Van Heest’s household.<br />

Martha, as she became in America, was the daughter of<br />

Simon’s second wife, Charlotte. The Van Heests briefly<br />

settled in Passaic, near Simon’s oldest son, Christian, the<br />

shoemaker who had apprenticed in Aart’s shop. Since<br />

John Breen and Charlotte had known each other in Ouddorp,<br />

it was no surprised that they were married in Passaic<br />

less than one year after her arrival. Their first son,<br />

Aaron, was baptized in the local Reformed church. A year<br />

and a half later, on November 26, 1856, Simon was born<br />

on the farm in Franklin Township, today’s Wyckoff. Nine<br />

more children followed, including a set of identical twins.<br />

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat. Pis<br />

et facerit eos resciae eos reribus,<br />

sum sit labo. Bus.Pid mi, ommod<br />

milique odiscim agnatem rem latur<br />

sequam sitas res sit et mod ut et<br />

enihictatur, que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

Simon spent most of his growing up years on a farm<br />

his father purchased along Goffle Road, next to the site<br />

where Braen’s Hawthorne quarry would be located. As<br />

a boy roaming the woods behind the farmhouse, Simon<br />

would have seen Vermeulen’s quarry and the nearby cemetery<br />

he also operated. Young Simon attended school on<br />

Goffle Road and toiled on the family farm. As a teenager<br />

he started working in Paterson’s locomotive shops, first at<br />

Cooke’s, and then at Rogers, where he became a “boss<br />

hammerman and machinist.” With a steady job to support<br />

himself, Simon married a second cousin, Mary Breen,<br />

on June 22, 1878. The newlyweds lived in a series of<br />

four-plexes within walking distance of the shops, in a<br />

neighborhood of immigrants from both the British Isles<br />

and the Netherlands. Simon and Mary gave their five<br />

children American versions of their own parents’ names:<br />

Martha, Nellie, John, Abram, and Cornelius. Along with<br />

his brothers Henry and Frank, Simon also began spelling<br />

his surname with an ‘a’ to match its actual pronunciation,<br />

and calling himself Samuel, a more common English name. Feeling underappreciated<br />

in the shops, and likely underpaid, Sam moved to the Paterson Iron<br />

Company to become a foreman. He proudly remembered etching his name on<br />

the new drive shaft for the queen of the Hudson River steamers, Mary Powell.<br />

Whatever his name, even as a young man Sam wanted to be remembered.<br />

During the spring of 1888, Sam’s world took a sudden turn when Mary delivered<br />

her fifth child in ten years. She never recovered from the ordeal and<br />

succumbed to kidney failure on April 1, less than two months after Cornelius’s<br />

birth. Now a single parent with five children under the age of ten, Sam quit his<br />

12 SECTION TITLE

Sam moved to the Paterson Iron Company to become a foreman.<br />

He proudly remembered etching his name on the new drive shaft for<br />

the queen of the Hudson River steamer, Mary Powell.<br />

foundry job with its fixed hours to make his living as a carpenter. He moved to another part of the city,<br />

nearer to the church he had been attending. Within a year he moved again, this time to the Totowa section,<br />

near the farm to which his parents had moved. He now combined blacksmithing with wheelwrighting and<br />

wagon-making. And in 1892 he remarried. Zoetje (Susan) de Krijger Dale had been born in the Netherlands,<br />

in village only a few miles east of Ouddorp. At three, she came to Paterson where her father made<br />

his living caning chairs. She married at fifteen and had three children when she married Sam. Susan and<br />

Sam abandoned worshiping in a Dutch immigrant church and joined the nearby Paterson Avenue Methodist<br />

Church, where they remained active members for the rest of their lives.<br />

Sam’s grandfather had come to America to be an independent person. Sam’s father followed that same<br />

path by becoming a farmer. Now Sam followed in their footsteps. He never again worked for a wage. He<br />

was known to say, “As long as you carry a dinner pail you get nowhere.” That he chose the path that led to<br />

the construction business reflected what many other sons of Dutch immigrants were doing in the Paterson<br />

area during this era. During the 1890s Paterson was an industrial boomtown, the third largest city in the<br />

state, and the fortieth largest city in the nation (today it ranks 178th). It produced more silk cloth than any<br />

other city in the country. The world’s largest dye house stood on the banks of the Passaic River. The locomotive<br />

shops built cutting edge technological marvels that approached speeds of one hundred miles per<br />

hour. And the Colt company built the gun that tamed the West. The city’s population doubled every twenty<br />

years. Nearby, Passaic, Garfield, and Lodi experienced similar growth. Immigrants poured into the Passaic<br />

Valley pushing the demand for housing, roads, water and sewer systems, and factories. By 1910 more<br />

than a third of the contractors and suppliers building those things in the Paterson area were either Dutch<br />

immigrants (like Sam’s uncle Martin) or the sons of the immigrants (like Sam himself). Beginning in 1902,<br />

in quick succession, Paterson endured three natural disasters that further spurred the construction trades:<br />

a fire, a flood, and a tornado. The needs for materials being so high, and the limits of wood construction<br />

so obvious, some eyes spotted a solid solution to the region’s needs. The hills to the west of the city were<br />

alive with rock, trap rock to be precise. That resource, and the Braen name, were fused together in 1904,<br />

at the foot of Passaic Falls.<br />

SECTION NUMBER 13

Legend says that Sam Braen acquired the<br />

Valley of the Rocks quarry as payment for a gambling debt.<br />

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat.<br />

Pis et facerit eos resciae eos<br />

reribus, sum sit labo. Bus.Pid<br />

mi, ommod milique odiscim<br />

agnatem rem latur sequam sitas<br />

res sit et mod ut et enihictatur,<br />

que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

14 SECTION TITLE

From Samuel Braen, Road Builder,<br />

to Samuel Braen’s Sons<br />

Legend says that Sam Braen acquired the Valley of the Rocks quarry as payment for a gambling debt. If<br />

true, the loser would likely have been another son of Dutch immigrants. Jacob Sandford and Sam were<br />

the same age. The parents of both were Ouddorp exiles. The Sandiforts arrived three years after the Aart<br />

Breen family. The Sandfords and the Breens were remotely related by marriage: Jacob being brother-in-law<br />

to one of Sam’s cousins. And both Sam and Jacob had tried their hands at various jobs. Jacob had gone<br />

from peddling vegetables from a wagon in 1880 to quarrying in 1895.<br />

Paterson began sprouting stone quarries during the 1890s. The first, New Jersey Blue Stone and New<br />

Jersey Brown Stone, appeared on the slopes of Garrett Mountain at New Street and Grand Street. Another<br />

company, owned by two sons of Dutch immigrants, Cornelius Verduin and Abram Hartley, worked a site at<br />

the foot of Van Houten Street, across the river from the Valley of the Rocks. Sandford worked this exposed<br />

cliff face off and on for about eight years. That he might have become indebted to Sam Braen, either at the<br />

gaming table or in the ledger books, would not have been an unusual situation, given how closely the various<br />

contractors and suppliers worked with, and lived near each other, and very often socialized together.<br />

As Paterson continued growing, construction methods changed. Already during the 1880s the local cities,<br />

Passaic being among the first, began replacing their wooden sidewalks with ones of more durable concrete<br />

and cement. These new wonder materials inspired Thomas Edison, to heavily invest in the business<br />

of building cast concrete houses. Although his company failed, concrete did catch on as paving material.<br />

Given the number of Dutch immigrants toiling as masons, it was only natural that some of them successfully<br />

bid on the sidewalk projects. Jacob Van Noordt of Passaic, another first generation Dutch-American,<br />

secured enough business to incorporate as the Union Building and Construction Company. He also enter<br />

politics to win a seat on the county Board of Freeholders. Soon after 1900 his nephew, Dow Drukker,<br />

became the head of this firm. Drukker lured in more investors, bought control of the local newspaper and<br />

Passaic’s largest bank, and added quarries and sand pits in Clifton and Riverdale to his holdings. When he<br />

became director of the board of freeholders he oversaw the county’s various construction projects: especially<br />

bridges and roads. In 1914 he won a seat in the United State House of Representatives. Drukker’s<br />

idea to link construction and supply together in one company provided a template Sam Braen would follow.<br />

Another early influence on Sam’s career was one of Paterson’s notable boosters, Nathan Barnert. An immi-<br />

SECTION NUMBER 15

grant from Poland, Barnert had parleyed the profits from his clothing business into real estate investments<br />

in the city, including ownership of some of its largest textile mill buildings. He also set the local standard<br />

for fighting corruption in city government during two combative terms as mayor. Around 1900, Barnert<br />

starting developing some of his holdings into residential neighborhoods in the northern fringes of the city,<br />

aiming to sell building lots to largely Dutch contractors who built houses to sell to Dutch millworkers. Sam<br />

Braen won the contract to pave the streets in Barnert’s development along Haledon Avenue.<br />

Both Drukker and Barnert taught another lesson for aspiring entrepreneurs, the importance of social connections.<br />

Sam followed suit by joining the Masons and other fraternal organizations, where he could meet<br />

with likeminded community leaders. Like Drukker, Sam became active in the Republican Party, which<br />

dominated the county’s politics then. But maybe just as importantly, Barnert set a very high standard<br />

for investing in the community where he thrived and genuinely promoting the welfare of his customers,<br />

neighbors, and employees. Barnert and his wife Miriam attached their names to a hospital, synagogue,<br />

and private school located in Paterson’s upscale neighborhood. While Sam never held public office, his<br />

fraternal memberships required him to be active in the wider community. As a Methodist he believed that<br />

faith produced better people and better communities. That prompted him to support financially the revival<br />

meetings the evangelist Billy Sunday held in the Paterson Armory during 1916. Since his Dutch Calvinist<br />

roots discouraged public displays of generosity, Sam’s public accolades finally appeared in his obituary.<br />

But his trucks and machines all boldly proclaimed, “SAMUEL BRAEN, ROAD BUILDER” or “SAMUEL<br />

BRAEN, CONTRACTOR.”<br />

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat. Pis et facerit eos resciae eos reribus, sum sit labo. Bus.Pid mi, ommod milique odiscim agnatem<br />

rem latur sequam sitas res sit et mod ut et enihictatur, que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

16 SECTION TITLE

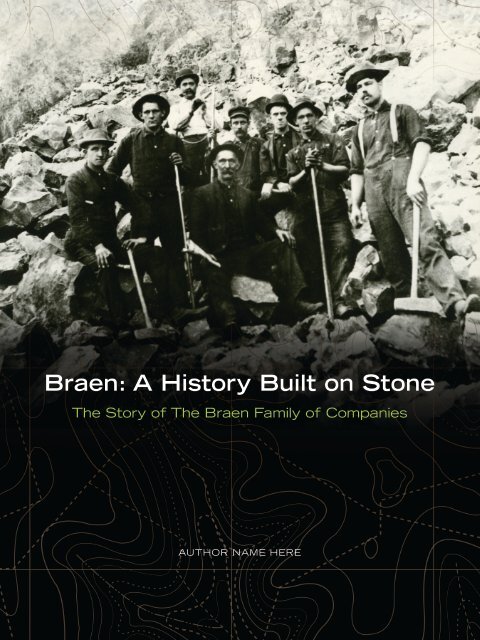

...Sam proudly hired a photographer to haul his equipment into the quarry<br />

to picture Sam, his sons, and their fellow workers surrounded by rocks.<br />

Sam and his brothers legally changed their surname’s<br />

spelling around the time of their father’s<br />

death in 1896. None of John Braen’s boys would<br />

be someone else’s employee. Aaron farmed in<br />

Hawthorne. Henry tried his hand as several businesses:<br />

commercial baking and printing among<br />

them. John stitched awnings before joining his<br />

brother Peter in the carpenter trade in Hawthorne.<br />

Frank became a mason; Martin also worked as a<br />

carpenter. Sam’s sisters (Cornelia, Gertrude, and<br />

Elizabeth) married a house painter, a mason, a<br />

metalworker, respectively. In one generation, John<br />

Braen’s son fulfilled the dream that inspired their<br />

grandfather Aart to immigrated in 1851. Each one<br />

of the Braen descendants had climbed a rung or<br />

two on the American social ladder. When their<br />

mother celebrated her seventieth birthday in 1902,<br />

the entire group gathered for a family portrait to<br />

mark her milestone.<br />

By then Sam had already established himself in the local construction business.<br />

Two years later, he took possession of his first quarry, a working site, complete<br />

with a crusher. It had major limitations. It was by the river, on a narrow shelf<br />

of land, with the crusher resting on the floor. In 1903, when the Passaic Valley<br />

experienced one of the worst floods in its recorded history, the quarry had been<br />

under water. There were no guarantees against another flood inundating the<br />

site in the future. The narrow floor, the presence of nearby buildings (including<br />

one of the city’s larger mills), and the river limited the size of the blasts. There<br />

simply was no room for the dislodged rocks to fall. Finally, because all the rocks<br />

fell to the floor, they had to be hoisted up into the crusher by a cart and counterweight<br />

device. This was slow, heavy, dangerous, and expensive. Nevertheless,<br />

Sam proudly hired a photographer to haul his equipment into the quarry to<br />

picture Sam, his sons, and their fellow workers surrounded by rocks. Sam held a<br />

newspaper in one hand; the others displayed their tools. The picture only hinted<br />

at the backbreaking nature of the actual work in 1908. They drilled by hand,<br />

with hammers driving the bits into the rock, smashing the oversized rocks with<br />

sledgehammers, then shoveling material into a cart. None of the men in the<br />

picture appeared overweight. And Sam did some of this work while in his fifties.<br />

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat. Pis et<br />

facerit eos resciae eos reribus, sum<br />

sit labo. Bus.Pid mi, ommod milique<br />

odiscim agnatem rem latur sequam<br />

sitas res sit et mod ut et enihictatur,<br />

que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

SECTION NUMBER 17

Beyond the hammers and chisels, they were learning to handle explosives, by trial and error. One noteworthy<br />

“oops” moment made the front page of the New York Times on January 12, 1907. Sam and his crew<br />

were blasting on a rock face along Hamburgh Turnpike (today’s West Broadway) only a few blocks from<br />

where Aart Breen’s shoeshop had been located. When Sam packed too large a charge into the hole “[a]<br />

shower of rocks passed through…heavy plate glass windows, demolishing…Corinthian columns and creating<br />

havoc generally in the interior…”, of an elaborate nearby house, the home of the father of Paterson’s<br />

renowned sculptor Gaetano Frederici. “…Samuel Braen believes that there was too much nitro-glycerine in<br />

the dynamite.” This particular lesson cost Sam about $10,000. His search for more rock led him to work<br />

on Garrett Mountain sites, where he was less likely to take out any houses, and keeping a safe distance<br />

from Lambert’s Castle.<br />

Cars and trucks became more common as Sam perfected his blasting skills. He quickly caught the driving<br />

bug. His new passion provided first hand knowledge that motor vehicles required better roads than horsedrawn<br />

wagons. That truth meant more pavement, more bridges, more culverts, more excavating, and more<br />

concrete. The farmers in places like Wayne, Clifton, Hawthorne, and Fair Lawn, whose livelihoods depended<br />

on delivering to markets in Passaic or Paterson, demanded improvements. The state government’s<br />

policy of carving new municipalities from the old townships produced a ‘borough-mania,’ with these minitowns<br />

vying for new residents. Passaic County’s Manchester Township dissolved into five boroughs (Totowa,<br />

Haledon, North Haledon, Prospect Park, Hawthorne) between 1898 and 1908. In Bergen County, nine<br />

municipalities became sixty-nine by the mid 1920s. Each new unit wanted sewers and water systems, plus<br />

paved streets. For a company like “Samuel Braen, Road Builder,” this meant business.<br />

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat. Pis et facerit eos resciae eos reribus, sum sit labo. Bus.Pid mi, ommod milique odiscim agnatem<br />

rem latur sequam sitas res sit et mod ut et enihictatur, que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

18 SECTION TITLE

As the demands and opportunities for excavation<br />

work increased, Sam bought bigger machines. By<br />

1917 he owned a massive (by the standards of the<br />

day) Marion steam rig that could be fitted with a<br />

shovel, clamshell, crane, or dragline. To move it, he<br />

needed to hire a local hauler who owned a truck with<br />

a specially equipped engine and transmission. Sam<br />

advertised his services in bold letters on his equipment<br />

and in the Paterson City Directory, variously<br />

calling himself a stone cutter, stone dealer, and general<br />

contractor. To save money he refused to rent or<br />

build any separate office space, instead operating the<br />

business from his home on Totowa Avenue. At times<br />

he would mix business with pleasure, using one of his<br />

trucks to carry passengers for a family outing.<br />

As Sam looked toward retirement, his sons John<br />

and Abram traded their hammers and bits for desks<br />

in an office. They also worked to secure a reliable<br />

source of traprock for making the concrete the roads,<br />

bridges, and sewers required. They looked to the First<br />

Watchung Mountain. It was clear there was rock to<br />

be had in the mountain, but how much, and of what<br />

quality was at best a guess, given the ability to drill<br />

core samples one hundred years ago. Back during<br />

the Civil War, Abraham Vermeulen, operated a site<br />

along Goffle Road, only to abandon it. A number<br />

of contractors began betting there were substantial<br />

quantities, based in part on the recommendations of<br />

newly minted geologists who were graduating from the new technical colleges<br />

and universities. They recommended New Street on Garrett Mountain, then<br />

Great Notch near Little Falls. Dow Drukker developed a site along Valley Road in<br />

Clifton. James and Richard Sowerbutt operated in three places: next to Drukker’s<br />

Clifton quarry, along with Haledon and Prospect Park. Their successes<br />

encouraged Sam and his sons to purchase their own site in Hawthorne, next<br />

to the Braen family farm on Goffle Road. Here gravity could do the work that<br />

lifting had done in the Valley of the Rocks. Stone blasted from the top of the<br />

hill, would be dumped down into the crushers, conveyed into the batch plants<br />

further down the slope, and then shipped out as sub-base, asphalt, concrete, or<br />

gravel. The Hawthorne quarry would operate for fifty years.<br />

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat. Pis et<br />

facerit eos resciae eos reribus, sum<br />

sit labo. Bus.Pid mi, ommod milique<br />

odiscim agnatem rem latur sequam<br />

sitas res sit et mod ut et enihictatur,<br />

que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

By the mid-1920s Sam felt financially secure enough to buy a modest farm and<br />

orange grove in Florida, and take the time to visit the place during the winter<br />

months. Increasingly his sons John and Abram took the reins of the business,<br />

especially after the purchase of the Hawthorne quarry. The boys had began<br />

SECTION NUMBER 19

CAPTION TITLE HERE: Apitat. Pis et facerit eos resciae eos reribus, sum sit labo. Bus.Pid mi, ommod milique odiscim agnatem<br />

rem latur sequam sitas res sit et mod ut et enihictatur, que rerferit, offictae si o<br />

working for their father on the small farm he owned along Totowa Avenue. They wielded hammers and<br />

shovels with the other laborers in the quarry. As the construction business grew, they became foremen,<br />

and then managers. John became the bookkeeper for the business, while Abram oversaw the operational<br />

side. When Sam’s health faltered in 1926, the business formally changed hands. John and Abe soon<br />

placed their own stamp on the business. The ads that for years had read “Samuel Braen, Road Builder,<br />

General Contractor, Manufacturer of Crushed Stone.” Now they read “Samuel Braen’s Sons.” And they had<br />

an office address, “Goffle Road, Hawthorne, New Jersey.<br />

Samuel Braen died at his home in Paterson on January 11,1930, his passing noted on the front page of<br />

the local newspapers. His lodge brothers gathered to honor him, along with his family, friends, and customers.<br />

Susan outlived him by fifteen years. Maybe the most significant testimony to the kind of man Sam<br />

had been could be found in two facts: his sons kept his name on the business, and he had a grandson who<br />

carried that name.<br />

20 SECTION TITLE

Enduring the Great Depression would be the next great hurdle Samuel Braen’s Sons would meet. If any<br />

business could cope in that economic situation, a quarry would be it. During the 1920s the construction<br />

business in northern New Jersey experienced a surge of activity spurred by projects like the Holland<br />

Tunnel in the early years and the George Washington Bridge at its close. The demand for aggregate and<br />

concrete for those monumental structures rippled through the entire region. In 1928, the Braen brothers<br />

added asphalt and concrete plants to the Hawthorne facility. With major projects under way, even ones at<br />

a distance, the batch plants paid for themselves. As the federal government spurred public works projects<br />

to reduce unemployment, Passaic and Bergen counties saw an increased demand for the products Samuel<br />

Braen’s Sons had to sell.<br />

In the depths of the Depression,<br />

the company expanded its holdings.<br />

Along with a third partner, the<br />

brothers formed Braen Sand and<br />

Gravel, with properties in Wyckoff,<br />

Franklin Lakes, and Mahwah to<br />

produce a new line of products. As<br />

their holdings increased, and the<br />

financing requirements changed,<br />

John and Abram legally incorporated<br />

as a privately held company,<br />

with each of them holding fifty<br />

percent of the shares. John was<br />

the president and treasurer, while<br />

Abram was named the firm’s vice<br />

president and secretary.<br />

The Hawthorne quarry remained<br />

the most visible industry in Hawthorne,<br />

and also one of the most<br />

valuable. It was one of the larger<br />

employers in the borough, along<br />

with the railroad yards and a<br />

dyehouse. It generated significant<br />

As the federal government spurred public works<br />

projects to reduce unemployment, Passaic and<br />

Bergen counties saw an increased demand for the<br />

products Samuel Braen’s Sons had to sell.<br />

revenue through the property taxes it paid. The trucks with the “Samuel Braen’s Sons” name on them also<br />

said “Hawthorne, New Jersey” right below the name. The brothers both maintained a high profile both in<br />

Hawthorne, where they worked, and in Totowa, where they lived. They were active in civic life. John belonged<br />

to Hawthorne’s Rotary Club and served on Totowa’s board of education and board of adjustment.<br />

Like their father, John and Abram both were active Masons.<br />

When the Second World War ended in 1945, John and Abram, looked toward retirement. By then their<br />

business had not only survived the depression and war years, it had actually grown. And with the end of<br />

the fighting, the region stood on the threshold of another construction boom, one that would drive the area<br />

and the company to dizzying heights during the next thirty years. Under a new generation of ownership, the<br />

Braen name would be known not just in North Jersey, but nationally.<br />

SECTION NUMBER 21