AFGHANISTAN

AFGHANISTAN

AFGHANISTAN

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL<br />

MAY 2007<br />

This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for<br />

International Development. It was prepared by ARD, Inc.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong><br />

GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE<br />

PROJECT (ALGAP)<br />

LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

Acknowledgments<br />

This Lessons Learned Review of the Afghanistan Local Governance Assistance Project (ALGAP) resulted<br />

from collaboration among the project staff and the ARD home office. The Review was written by Kim<br />

G. Glenn and produced by ARD, Inc. ARD would like to acknowledge a number of people who<br />

contributed substantively to the Review. They include Douglas Grube, the chief of party for ALGAP<br />

who brings a comprehensive understanding of all the project activities and the project history from its<br />

inception. The ALGAP staff contributed notably candid observations and insights rooted in their firsthand<br />

understanding of the project activities in the field and the context of the Afghan culture and reality.<br />

USAID implementing partners associated with national and subnational governance made substantial<br />

contribution through their meetings with Mr. Glenn. Mr. Glenn also met with representatives of<br />

Provincial Councils and government in the provinces of Baghlan, Kunduz, and Samangan whose<br />

observations and comments added depth, credibility, and context. See Appendix B for a list of key<br />

interviewees. Recognition also goes to ARD’s Senior Technical Advisor, Steve Reid, and the USAID<br />

Cognizant Technical Officer, Mohamed Zahar, who gave valuable guidance and support.<br />

Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development, USAID Contract Number<br />

AEP-1-809-00-00016-00, Task Order 809, under the Technical Services to Support USAID Global<br />

Bureau's Center for Democracy and Governance (G/DG) in Strengthening Democracy and Good<br />

Governance: Decentralization, Participatory Government, and Public Management (Decentralization)<br />

Indefinite Quantity Contract (IQC).<br />

Implemented by:<br />

ARD, Inc.<br />

P.O. Box 1397<br />

Burlington, VT 05402<br />

COVER PHOTO: The Provincial Council: A Bridge for the People. Courtesy Sayara Media and Communication,<br />

Afghanistan (http://www.sayara-media.com)

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL<br />

GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE<br />

PROJECT (ALGAP)<br />

LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW<br />

MAY 2007<br />

DISCLAIMER<br />

The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United<br />

States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

CONTENTS<br />

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................ iii<br />

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... v<br />

1.0 METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................... 1<br />

2.0 GOVERNANCE IN <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong>: AN OVERVIEW .......................................... 3<br />

2.1 GOVERNMENT STRUCTURES....................................................................................................... 3<br />

2.2 SUBNATIONAL GOVERNMENT RELATIONSHIPS ........................................................................ 4<br />

2.3 EMERGING TRENDS IN GOVERNANCE ........................................................................................ 5<br />

3.0 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT: AN<br />

OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................... 7<br />

3.1 PURPOSE....................................................................................................................................... 7<br />

3.2 EVOLUTION FROM THE <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> STABILIZATION PROGRAM (ASP) ERA..................... 7<br />

3.3 APPROACH................................................................................................................................... 8<br />

3.4 COMPONENTS ............................................................................................................................. 9<br />

3.4.1 Capacity Building....................................................................................................... 9<br />

3.4.2 Civic Education........................................................................................................10<br />

3.4.3 Facilitation Development ......................................................................................11<br />

4.0 FINDINGS ................................................................................................................... 13<br />

4.1 PROVINCIAL COUNCILS............................................................................................................13<br />

4.1.1 Resolve Disputes.....................................................................................................13<br />

4.1.2 Act as an Oversight Body .....................................................................................14<br />

4.1.3 Are the Voice of the People.................................................................................15<br />

4.1.4 Add Local Leadership for Addressing National Issues....................................15<br />

4.2 CAPACITY BUILDING ACTIVITIES..............................................................................................15<br />

4.2.1 Lessons from Workshops.....................................................................................16<br />

4.2.2 Consultation Tours, Possibly the Most Important Activity ...........................17<br />

4.2.3 Conferences and Provincial Exchanges; Sometimes “Conferring” is Enough<br />

....................................................................................................................................17<br />

4.3 CIVIC EDUCATION ACTIVITIES.................................................................................................17<br />

4.3.1 Roundtables: Radio and TV Require Special Formats.....................................18<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW i

4.3.2 Lessons from the Successful Mobile Theater....................................................18<br />

4.3.3 Lessons Regarding Mass Media ............................................................................18<br />

4.4 PROJECT MANAGEMENT ...........................................................................................................19<br />

4.4.1 Fly Without a Pilot .................................................................................................19<br />

4.4.2 Recruit Locally.........................................................................................................19<br />

4.4.3 Avoid Field-Based Project Offices.......................................................................20<br />

4.4.4 Proceed with or without a National Government Counterpart..................20<br />

4.4.5 Build Capacity at District Levels..........................................................................20<br />

4.4.6 Extend Support to Provincial Government Actors.........................................21<br />

4.4.7 Anticipate Need to Build Capacity Everywhere...............................................21<br />

4.5 GENDER......................................................................................................................................21<br />

4.5.1 Budget and Plan for Maharam ..............................................................................21<br />

4.5.2 Provide Gender Training for Project Staff and Activity Participants............22<br />

5.0 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS..................................................... 23<br />

APPENDICES .................................................................................................................... 25<br />

APPENDIX A: BIBLIOGRAPHY .................................................................................. A-1<br />

APPENDIX B: LIST OF INTERVIEWEES................................................................... B-1<br />

APPENDIX C: PROVINCIAL COUNCIL LAW ARTICLE 4 .................................... C-1<br />

ii <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

ACRONYMS AND<br />

ABBREVIATIONS<br />

ALGAP Afghanistan Local Governance Assistance Project<br />

APM Advanced Participatory Methods<br />

AREU Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit<br />

ASP Afghanistan Stabilization Program<br />

CDC Community Development Committee<br />

COP Chief of party<br />

CSO Civil society organization<br />

CTO Cognizant technical officer<br />

FCCS Foundation for Culture and Civil Society<br />

ISAF International Security Assistance Force<br />

MRRD Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development<br />

NGO Nongovernmental organization<br />

NSP National Solidarity Program<br />

PBF Province-based facilitator<br />

PDC Provincial Development Committee<br />

UNDP United Nations Development Program<br />

USAID United States Agency for International Development<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW iii

INTRODUCTION<br />

After more than 25 years of almost constant war, Afghanistan is re-creating itself politically, economically,<br />

socially, culturally, and governmentally. Part of this re-development calls for unprecedented representative<br />

subnational governance with revitalized or new structures. These include Provincial, District, and Village<br />

Councils. Accompanying these structures are opportunities and mechanisms for greater citizen participation in<br />

governance within provinces.<br />

ALGAP’s mission between November 2005 and June 2007 has been to support the development of the<br />

capacity of the newly-elected and formed Provincial Councils to fulfill their roles and responsibilities. In the<br />

process, ALGAP has contributed to the development of an environment in which the government, councils,<br />

public, civil society, and businesses, can begin to work together effectively.<br />

ALGAP organized a civic education campaign prior to the September 2005 Provincial Council elections,<br />

designed to inform the public and the candidates for Provincial Councils about the legal status and role of the<br />

Councils in accordance with the Constitution and the newly promulgated Provincial Council Law.<br />

Immediately following the election and the swearing in of the successful Council members, ALGAP provided<br />

an orientation and organization program for the Council members. Subsequently, ALGAP has carried out a<br />

wide array of training and technical assistance activities aimed at strengthening the capacity of the Councils to<br />

fulfill their roles and responsibilities. At the request of the Provincial Councils and other provincial governance<br />

actors, ALGAP has expanded its technical support program over the past year to include participants from the<br />

various government ministries working at the provincial and district levels. The project also initiated a national<br />

civic education campaign to promote greater citizen participation in governance within the provinces.<br />

With a few months left in the project, USAID encouraged ARD to assess the technical and administrative<br />

aspects of the ALGAP project that did and did not “work,” in order to provide recommendations for similar<br />

future USAID programs. For the purposes of this Review, we define something that “worked” as a project<br />

activity, policy, or approach that met its intended purpose particularly well and is worth considering in other<br />

project contexts. Something that did not “work,” in this sense, is something that failed in a surprising or<br />

notable fashion, which is also worth considering in other project contexts.<br />

At the request of USAID, this Lessons Learned Review also addresses the broad question of support to the<br />

Provincial Councils: whether or to what extent they should continue to receive support from USAID, the<br />

Afghan government, or from other donors. The governance context in Afghanistan is in rapid transition and<br />

the strategic questions surrounding subnational governance are critical. Further, during the 18 months of<br />

ALGAP’s implementation, Afghan government support for Provincial Councils and for provincial governance<br />

in general has been erratic. In taking stock of efforts to improve governance and state-building in Afghanistan,<br />

donors have recognized the need for a more coherent strategy for subnational governance and for better<br />

coordination of initiatives. Therefore, in addition to lessons on project implementation, USAID specifically<br />

requested, to the extent that the Review findings support them, clear conclusions and recommendations<br />

regarding immediate and future support to subnational governance in Afghanistan.<br />

This report concludes that the Provincial Councils, despite limited resources and mandated authorities, are<br />

making a useful contribution to subnational governance in a number of areas, including conflict and dispute<br />

mediation, and oversight of provincial government activities. Furthermore, the Councils appear to be filling a<br />

critical role as representatives of the population in the provinces, communicating their needs to government<br />

administration, and advocating for improved security, public services, and infrastructure. Though they show<br />

early promise, the Provincial Councils are currently at a very rudimentary stage in their evolution. Carefully<br />

targeted, well-designed training and technical assistance to the Provincial Councils over the next several years,<br />

combined with civic education campaigns aimed at the general public, would do much to speed their evolution<br />

and improve their effectiveness.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW v

1.0 METHODOLOGY<br />

A “lesson learned” for this exercise derives from an activity, policy,<br />

or approach that is either reported or observed as having<br />

“worked”; that is to say, it seems to have been well received or<br />

effective in achieving its intended goals or outcomes. Alternatively,<br />

a “lesson learned” may derive from an activity, policy, or approach<br />

that notably did not work. In both cases, the “lesson learned” could<br />

reasonably be recommended for use in future projects in<br />

subnational governance in general, or for projects specifically in<br />

Afghanistan regardless of the project objectives.<br />

The Review took a multi-faceted approach to obtain answers and<br />

insights into ALGAP, its goals, processes, and accomplishments.<br />

The approach involved the review of program documents and<br />

records, and individual and group interviews with ALGAP staff,<br />

Provincial Council members, provincial government officials, and<br />

other provincial governance actors. The consultant made two field<br />

visits to observe ALGAP-implemented workshops. He also<br />

conducted individual and group interviews and discussions with<br />

ARD home office staff and USAID/Afghanistan personnel.<br />

The major documents reviewed were:<br />

• annual work plans and reports;<br />

• monthly and quarterly activity and progress reports;<br />

• ad hoc and formal studies or evaluations 1;<br />

• success stories prepared in March 2007; and,<br />

• short-term technical assistance consulting reports.<br />

At the outset of the Review, the consultant identified the key elements of the ALGAP design, implementation<br />

challenges, primary operational processes, and major programmatic successes. The consultant met with the<br />

USAID cognizant technical officer (CTO), and key project staff to discuss the results of the initial review and<br />

interviews and to identify the chief areas of importance. The six major areas identified were: project<br />

management, gender, workshops, consultation tours, conferences, and civic education.<br />

This Lessons Learned Review attempted to answer three simple questions with regard to technical assistance to<br />

the Provincial Councils and the civic education activities. Broadly speaking, the responses from nearly everyone<br />

associated with the project, as well as the documentation reviewed, provided correspondingly simple answers:<br />

1. What worked? Everything.<br />

2. What didn’t work? Nothing.<br />

3. What next? More of the same.<br />

Before the offices of the Jawzjan<br />

Provincial Council, from left:<br />

Council Secretary Alifsha Khan<br />

and Council President Molawi<br />

Abdul Ghani.<br />

1 See the bibliography in Appendix A for a list of key documents contributing to this Lessons Learned Review.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 1<br />

PHOTO COURTESY OF ALGAP PROJECT

On the surface these responses suggest great successes. Yet the relative progress towards meeting the immense<br />

needs of Afghanistan remains extremely limited. Building a healthy subnational governance environment in<br />

Afghanistan, in the broad sense, remains a very long-term goal towards which ALGAP has made significant,<br />

but necessarily initial, “baby” steps.<br />

It was necessary to undertake extensive probing to reveal anything that could be considered a “lesson learned”<br />

and not simply an observation. Just because something “worked” doesn’t necessarily carry with it a lesson that<br />

can be applied elsewhere. Two major reasons for this cautious approach were discovered.<br />

• ALGAP was responding to such a clear and dramatic need that beneficiaries, especially the Provincial<br />

Councils, valued and appreciated its activities highly. To a starving person, almost any food will taste good.<br />

• In any circumstance, but especially within the Afghan culture, it is hard to persuade people to be critical, to<br />

admit that something did not work as expected, and to analyze why, and thereby extract a lesson.<br />

The circumstances in Afghanistan are so unusual and so fluid that any lesson learned will not easily be<br />

applicable to other projects elsewhere, or even subsequent projects in Afghanistan.<br />

2 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

2.0 GOVERNANCE IN<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong>: AN OVERVIEW<br />

The Afghanistan Local Governance Assistance Project has operated in a complex, fluid, and emerging<br />

governance environment. The national government, as well as the overall governance processes and actors, are<br />

undergoing significant change. The central government is seeking to increase its capacity to fulfill its<br />

responsibilities. These changes involve regular reviews and efforts to restructure the government, initiatives to<br />

increase the capacity of individuals and organizations within the government, and reconsideration of some<br />

traditional government roles.<br />

At the same time, the transition environment is forming new governance bodies and modifying the role and<br />

function of traditional bodies. Major changes include, but are not limited to, the formation of a new National<br />

Assembly as well as the formation of Provincial Councils as provided for in the constitution that was adopted<br />

in 2004.<br />

2.1 GOVERNMENT STRUCTURES<br />

National government: The central government, of course, remains a major governance actor at both the<br />

center and in the provinces. Indeed, in terms of decision making the central government has been the major<br />

actor, although it has been relatively weak in terms of enforcing policies and laws.<br />

National Assembly: Governance in Afghanistan encompasses a host of new formal structures as well as the<br />

traditional and semi-formal structures and processes. The National Assembly 2 is a legislative body that was<br />

elected in September 2005. The National Assembly is comprised of two houses and represents the provinces,<br />

enacts legislation, and must approve the appointment of ministers and other key government officials.<br />

Provincial Council: Provincial Councils, also elected in 2005, primarily have an advisory role. Their major<br />

authority under the Provincial Council Law promulgated in 2005 is the election of one of their members to the<br />

Mishrano Jirga, the upper house of the National Assembly. Other roles include facilitating communication<br />

between the government and the people and participating in or supporting a broad range of provincial<br />

activities.<br />

District and Village Councils: Also provided for in the Constitution is the election of District and Village<br />

Councils. The roles and responsibilities of these bodies is not clearly stated in the Constitution nor has there<br />

been enabling legislation to define these. Like the Provincial Councils, the District Councils will have the<br />

authority to elect one-third of the members of the Mishrano Jirga. Initially, it was intended that the District<br />

Councils would also be elected in 2005 along with the National Assembly and the Provincial Councils. This<br />

election was not held, however, and no date has been fixed to hold it.<br />

Traditional shuras, jirgas, and leaders: Governance in Afghanistan, at all levels, typically includes informal<br />

or semi-formal councils (shuras in Arabic and Dari, and jirgas in Pashto), commonly comprised of elders,<br />

mullahs, local commanders, and other respected male members of the country, province, district, or village, as<br />

well as respected individual leaders. While these shuras and jirgas, and the traditional leaders forming them, do<br />

2 Reference is frequently made in Afghanistan to the “parliament”. Officially, however, there is a National Assembly and a presidential form of<br />

government rather than a parliamentary form of government.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 3

not have formal authority within the governance structure, they have and continue to exercise significant<br />

influence on decisions affecting their respective villages, districts, and provinces. Additionally, some traditional<br />

leaders have direct informal ties and relations with both the central administration and with the National<br />

Assembly. At times the shuras and jirgas fulfill primary decision-making functions and are called upon to help<br />

resolve disputes between individuals, groups, tribes, and even provinces.<br />

Civil society, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and others: A variety of civil society<br />

organizations (CSOs) and NGOs, professional associations, and others are emerging in Afghanistan as<br />

governance actors. The project did not work extensively with them. However, in some instances Provincial<br />

Councils, recognizing their importance, included them in the workshops and other ALGAP-supported<br />

activities. These actors merit mention as an emerging part of governance throughout Afghanistan.<br />

Provinces, districts, villages, and municipalities: Administratively and politically Afghanistan is comprised<br />

of 34 provinces, approximately 239 3 districts, approximately 30,000 villages, and 217 municipalities. The<br />

provinces have been grouped by international agencies and the central government into regions (often eight,<br />

but sometimes fewer). These regions currently have little, if any, administrative or governance significance. The<br />

government is comprised of 26 ministries and a variety of independent bodies, e.g., the Administrative Reform<br />

and Civil Service Commission.<br />

2.2 SUBNATIONAL GOVERNMENT RELATIONSHIPS<br />

The central government is represented in provinces by a governor who is appointed by the president and<br />

reports to him through the Ministry of Interior. Each province typically has an office for some or all of the<br />

other line ministries. Large provinces are likely to have more offices than the 26 corresponding ministries, with<br />

multiple offices from one ministry and representation from independent agencies.<br />

The governor, the deputy governor, and the director of administration exercise substantial power and authority<br />

over events within the provinces and the actions of other government offices within their province.<br />

The provincial offices of line ministries formally report directly to their respective ministries in Kabul and not<br />

to the governor. They are, however, subject to influence from the governor and typically seek his or her<br />

approval or concurrence on major activities.<br />

A similar structure exists, in principle, at the district level. However, the number of district offices of line<br />

ministries is typically fewer than at the provincial level. The district governor 4 reports and is responsible<br />

directly to the provincial governor. The line ministry offices in the districts report indirectly to the district<br />

governor and directly to the provincial-level line ministry offices.<br />

The result of the centralized structure is that officially very few governance decisions are made at the province,<br />

district, or village levels. Program priorities and questions are referred up the chain of command of each line<br />

ministry for a decision, albeit with some recommendation from the provincial governor. The provincial<br />

governor is likely to be able to exert some influence on decisions even at the ministerial level, due to his or her<br />

relationship with, and appointment by, the president. 5<br />

Governance has been largely closed to direct or extensive citizen participation. The major avenues for public<br />

involvement have been through the traditional shuras or jirgas, and traditional leaders of a district, province, or<br />

other entity (in many cases a tribal grouping).<br />

3 The number of districts is in flux since some district boundaries have not been finally established. Similarly, references are made periodically<br />

to the possible creation of new provinces, with at least two provinces having been created within the past five years.<br />

4 The position is referred by various terms: governor, director, and administrator.<br />

5 There are a host of other factors that can influence the power and authority of a governor, including ethnicity and language as well as ties<br />

with other influential persons or with members of the National Assembly.<br />

4 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

2.3 EMERGING TRENDS IN GOVERNANCE<br />

While there is a clear emphasis in Afghanistan on a strong central government, and a highly centralized form of<br />

government in general, trends during the ALGAP project show some clear progress toward subnational<br />

governance. These trends may be reinforced by historic and traditional local governance structures. The<br />

Constitution provides for both some degree of delegation of authority and an increase in public participation in<br />

decision making, at least with respect to development.<br />

The government, while preserving the principle of centralism, shall delegate certain authorities to<br />

local administration units 6 for the purpose of expediting and promoting economic, social, and<br />

cultural affairs, and increasing the participation of people in the development of the nation. (Article<br />

137, 2004 Constitution)<br />

The Constitution, adopted by the Loya Jirga on 4 January 2004 (Afghan year 1382), affirms a “unitary state”<br />

government in Afghanistan with highly centralized administration and decision making.<br />

Many government leaders tend to subscribe to a belief that a centralized government structure is required for<br />

development and security. They note that while the government is officially centralized in terms of decision<br />

making, it is in fact weak in many ways. For example, difficulties have been encountered in transferring tax<br />

revenues from the provinces to the central government. It is also difficult to obtain and implement<br />

comprehensive plans or policies within the provinces. Moreover, some governors function with a high degree<br />

of autonomy and with little loyalty to, or support from, the central government.<br />

The international aid community places a similar emphasis on the development and maintenance of a strong<br />

centralized government. Many among them feel that only a strong central government can deliver the<br />

important reconstruction necessary to rebuild the country.<br />

The central government, with the support and encouragement of donors, is placing a high priority on the<br />

development of the capacity of the central ministries. It is common practice for central ministries to have, for<br />

example, large cadres of expatriate and local advisors and thereby to obtain financial assistance for equipment<br />

and materials to reinforce or further develop them.<br />

Articles 138 and 139 provide for an increase in citizen participation in governance through the establishment<br />

of Provincial Councils by free, direct, secret ballot.<br />

The provincial council takes part in securing the developmental targets of the state and improving its<br />

affairs in a way stated in the law, and gives advice on important issues falling within the domain of the<br />

province. Provincial councils perform their duties in cooperation with the provincial administration.<br />

(Article 139)<br />

The roles, functions, and authorities of the Provincial Councils, as defined in the Provincial Council Law<br />

promulgated in August 2005, are vague and limited. Nevertheless, the Councils are clearly intended to be an<br />

avenue for communication between the government and the people and a mechanism for citizen access to and<br />

participation in governance. (See Appendix C for Article 4 of the Provincial Council Law itemizing the<br />

principal duties and responsibilities of the Councils.)<br />

Additional opportunity for citizen participation is provided in Article 140 of the Constitution. This articles calls<br />

for the establishment of district and village councils through direct elections. Elections for the District<br />

Councils, also originally scheduled for September 2005, have been postponed. It is not yet clear when, or<br />

whether, they will be take place, nor is it clear what roles and responsibilities the District Councils might have.<br />

Elections for the Village Councils are not yet scheduled.<br />

6 “Local Administration Units” are the local offices of the line ministries.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 5

Traditionally, direct citizen involvement in governance has been minimal, exercised through shuras and jirgas<br />

whose membership comprised those (i.e., exclusively men) who had de facto power and authority, if not respect,<br />

among the local population. Women typically have been excluded from participation and this pattern persists,<br />

although some efforts are being made to correct the situation. Notably, by law, 30 percent of a Provincial<br />

Council’s members must be female.<br />

Some structures are being developed by the government and by donors to provide greater opportunity for<br />

public participation in development planning and implementation. Community development committees<br />

(CDCs) have been formed with NGO or international donor encouragement and support. The purpose of<br />

these CDCs has been to include citizens in both identifying community needs and in implementing projects<br />

developed to address those needs.<br />

Religious leaders have traditionally played an important role in local governance and they continue to do so. In<br />

areas where radio and television are not available or where illiteracy is widespread, a mullah’s voice may be the<br />

only form of “mass media” available. Indeed, even today, mullahs are often solicited by government or other<br />

parties to help spread messages or rally action by the public. Recent research suggests, however, that many<br />

Afghans do not consider their mullahs well-versed in teachings of the Koran and feel that they lack<br />

understanding of other Islamic sects. 7 Unless they receive training and are included in development activities,<br />

they may not be prepared to tolerate, let alone support, changes in custom whether those changes are<br />

motivated locally or from outside influences. Such changes would include the role of women and the<br />

application of democratic governance.<br />

Popular support for the new Provincial Councils, at least in principle, has been evident among local voters.<br />

Studies by the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) indicate that, at least in parts of<br />

Afghanistan, citizens increasingly accept and want more locally representative and inclusive structures. Voting<br />

patterns reflected in the Constitutional Loya Jirga (Assembly) and the National Solidarity Program’s community<br />

development committees (CDCs) suggest that when people are confident that their vote will be kept secret,<br />

they tend to elect people other than traditional leaders, especially when those leaders are viewed as corrupt or<br />

linked with criminal activities. 8<br />

Thus, on the one hand, we have a strong popular and constitutional emphasis on central government and<br />

authority. And on the other hand, we have specific provision in the constitution for local governance<br />

combined with a strong tradition of local governance customs. The emergence of the Provincial Councils has<br />

taken place within this conflicted context.<br />

7 Fidai, M. Halim. “How Afghans View Civil Society.” February 2006.<br />

8 Lister, Sarah. “Caught in Confusion: Local Governance Structures in Afghanistan.” March 2005.<br />

6 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

3.0 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL<br />

GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE<br />

PROJECT: AN OVERVIEW<br />

3.1 PURPOSE<br />

While ALGAP has undergone several modifications, its broad purpose has been consistent––to strengthen<br />

subnational government and governance. This has been interpreted to mean increasing the technical<br />

capabilities of government officials, and later and for most of the project, increasing the technical capabilities<br />

of Provincial Council members as well as other provincial governance actors 9.<br />

The purpose of the project as it became increasingly focused on Provincial Councils and provincial governance<br />

was to help develop the ability of Provincial Council members to recognize and fulfill their roles and<br />

responsibilities. An integral dimension of this was developing their ability to effectively relate with the<br />

government and other non-government actors and to establish and maintain the Provincial Councils’ positions<br />

as the only directly-elected bodies in Afghanistan.<br />

Of necessity, a collateral ALGAP purpose has been to contribute to the development of capacity-building<br />

resources in Afghanistan. ALGAP needed a group of individuals with training and facilitation skills, including<br />

the ability to assess needs, design work-based learning opportunities, facilitate workshops and other group<br />

learning events, and to be able to mentor other, less-experienced trainers and facilitators, as well as to utilize<br />

their abilities in support of Provincial Councils. It became clear at the outset of the project that it simply was<br />

not possible to locate individuals with the level of experience required. Thus ALGAP determined that it would<br />

be necessary to “grow its own” professional staff. In the long run, taking this approach had the advantage of<br />

contributing to the overall training/facilitation capacity within the country.<br />

3.2 EVOLUTION FROM THE <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> STABILIZATION PROGRAM<br />

(ASP) ERA<br />

The ALGAP focus underwent significant change between October 2004 and October 2005. Initially ALGAP<br />

was to support the Afghanistan Stabilization Program (ASP) and the development of district administration.<br />

This support was to include the supervision of construction being undertaken by ASP in the districts. Within<br />

this broad mandate the project was to provide technical assistance to ASP in the area of training, capacity<br />

building, and administrative reform. Due to internal ASP and Ministry of Interior conditions it proved to be<br />

unrealistic to pursue this assignment. During the first year, USAID also asked ALGAP to assist with the<br />

development of alternative livelihood programs, counter-narcotics programs, and to provide technical advice<br />

9 In Afghanistan citizens do not consider Provincial Councils as “government” and their members as “government officials.” ALGAP support<br />

to government officials refers to provincial governors and line ministry officials.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 7

with respect to some Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development’s (MRRD) National Solidarity<br />

Program (NSP) efforts to develop community development committees. While short-term assistance was<br />

provided, ARD and the USAID Democracy and Governance Office defined a focus that was more directly<br />

relevant to the initial purpose of the project:. Concerted preparation for providing on-going direct technical<br />

assistance to the Provincial Councils began in December 2005.<br />

Before the election, ALGAP had become involved with Provincial Council issues related to the election<br />

process. This initial assistance was in the form of organizing and conducting a pre-election nationwide<br />

information program regarding the newly-passed Provincial Law and the role and function of Provincial<br />

Councils. At that time, the major election focus was on the National Assembly with very little attention being<br />

given to the Provincial Council elections. ALGAP was able to help fill this void.<br />

The ALGAP public information program was directed primarily toward the Provincial Council candidates. The<br />

intent was to assist them in acquiring a clearer concept of the position for which they were running.<br />

Simultaneously, but with less emphasis, ALGAP sponsored public information spots on radio and television to<br />

help the public become informed about the Provincial Council election and its importance for them.<br />

In November 2005, shortly after the election, ALGAP prepared and implemented Provincial Council<br />

orientation and organization workshops in 33 of 34 provinces for newly elected Council members. 10 The<br />

donors and government realized that no real provisions had been made for the Provincial Councils following<br />

the elections. Indeed no provision had been made to swear in the councilors, to provide office or meeting<br />

space for them, or to insure that they had any operating resources.<br />

With encouragement from the Afghan government, USAID, and other international donors, ALGAP began to<br />

identify, develop, and provide needed technical assistance and support to Provincial Councils. After<br />

approximately six months of activity, a logical modification was made to the ALGAP Provincial Council<br />

assistance efforts. Provincial line ministry offices (administrative departments), governors’ offices, and<br />

Provincial Councils requested that technical assistance also be provided to a broader range of provincial<br />

governance actors. These requests came as ALGAP and the Provincial Councils more fully recognized that it<br />

was necessary for the Councils to build solid working relationships with the provincial administration<br />

(provincial governor, line ministry offices, and other actors within the province).<br />

Thus, since late 2006, ALGAP made technical assistance available to other provincial governance actors. This<br />

expanded the scope of the ALGAP work but enabled it to increase the use of the workshop materials and skills<br />

that were being developed.<br />

3.3 APPROACH<br />

To support Provincial Council members in developing the skills and abilities required to fulfill their roles,<br />

responsibilities, and functions as specified in the Provincial Council Law, ALGAP developed and has used a<br />

broad range of activities. Underlying these activities has been a commitment to several principles:<br />

1. Demand driven. To the extent possible, ALGAP has tried to respond to needs articulated by Provincial<br />

Councils and later by some government and other provincial governance actors. The intent, if not always<br />

the practice, has been to tailor capacity-building to specific, real, work-related needs<br />

2. Work-focused. The various capacity development opportunities have been focused on tasks or<br />

responsibilities being undertaken by the Councils or other provincial governance actors. At the outset of<br />

the project some of these were identified by ALGAP on the basis of an assessment of the Provincial Law<br />

and the skills required for the Councils to fulfill their roles and responsibilities.<br />

10 Thirty of the 33 orientation workshops were conducted simultaneously in the respective provinces. Three were conducted within a few<br />

days after the election and installation of the provincial council members and following the resolution of some election challenges. For<br />

security reasons it was not possible to conduct the workshop in Uruzgan, the 34 th province.<br />

8 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

3. Learn by doing. For most of the capacity-building activities, the Provincial Councils were asked and<br />

expected to assume some responsibility for planning and implementing them, for example, provincial<br />

consultations.<br />

4. Work nationally. In part out of necessity and in part by design, ALGAP assumed what many viewed as a<br />

high-risk approach—i.e., working in all provinces. The advantage of this approach is that no one was left<br />

out. The determining factor for levels of assistance from ALGAP was the extent to which Provincial<br />

Councils exercised their initiative and manifested a desire to obtain technical assistance.<br />

Following these principles, ALGAP provided various forms of technical assistance and support for the 34<br />

Councils 11 to develop the skills and abilities required to retain their independence while being a positive actor<br />

in provincial governance within the terms of the Constitution and the Provincial Council Law 12.<br />

3.4 COMPONENTS<br />

To fulfill project objectives, ALGAP developed three major program components: capacity building, civic<br />

education, and facilitation development.<br />

3.4.1 Capacity Building<br />

ALGAP’s capacity building component has encompassed a broad range of “learning and doing” activities.<br />

Six basic workshop modules were developed to respond to the needs of Provincial Council members to<br />

fulfill their responsibilities under the Provincial Council Law, the Provincial Council, and its relationships. The<br />

modules included:<br />

• PC and its Relationships,<br />

• Information Gathering for Planning,<br />

• Basic Administration Skills,<br />

• Meeting Management and Facilitation,<br />

• Action Planning, and<br />

• Introduction to the Budget Process.<br />

Supplemental workshop modules were outlined and<br />

utilized at the initiative of the province-based facilitators<br />

(PBFs) as they responded to needs expressed by the<br />

Provincial Councils, including:<br />

• Security,<br />

• Violence against Women, and<br />

• Media Relations.<br />

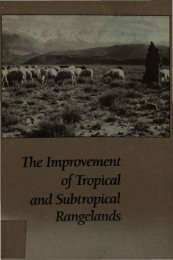

Kandahar Provincial Councilor, Haji M.<br />

Qasim, during PC Organization/<br />

Orientation Workshop, 23 November<br />

2005.<br />

11 ALGAP continued to seek ways to work with all 34 provinces. It was, however, not possible to provide assistance to Uruzgan Province due<br />

to security conditions that greatly restricted travel to or from the province.<br />

12 A revision of the 2005 Provincial Council Law has been approved by both houses of the National Assembly and is, as of March 2007,<br />

reportedly ready for signing by the president. This revision gives provincial councils greater formal responsibility and power.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 9<br />

PHOTO COURTESY OF ALGAP PROJECT

Consultation visits by Provincial Council members to districts within their province. An early request from<br />

Provincial Councils was for assistance in visiting the districts within their provinces. A repeated comment from<br />

Provincial Council members was that while they were from the province, most of them had little firsthand<br />

knowledge about it. Indeed, most had not traveled widely within the province even during the election<br />

campaign. ALGAP provided the Councils with technical assistance in planning the visits and in preparing<br />

formats for recording and analyzing the information they would gather.<br />

The first round of ALGAP-supported consultations was undertaken in the period of April-June 2006. These<br />

included only Provincial Council members and were of short duration. The provincial consultations were<br />

modified for a second round in 2007. For these consultations the Provincial Councils could and did invite<br />

provincial administration and other provincial governance actors to participate. ALGAP provided financial<br />

support for all of the participants, within the guidelines it had established.<br />

Basic office equipment and supplies were provided early in the Provincial Council term to enable them to<br />

begin to operate. The Provincial Councils lacked even the most basic equipment and supplies and were not yet<br />

receiving any operating funds. In addition to pens, paper, markers, envelopes and other clerical supplies,<br />

ALGAP provided each Council with a filing cabinet and a choice of three cell phones with $50 pre-paid calling<br />

per phone, or a satellite phone for provinces without cellular network access. The project issued five satellite<br />

phones and 84 cell phones to 33 of the 34 provinces (Uruzgan excepted). Effective communication for the<br />

Councils was an important component of project support.<br />

Conference support: Since their formation, the Councils as well as the central government have solicited<br />

ALGAP for support in organizing, conducting, and financing conferences in order to exchange information<br />

and ideas on problems of common interest and to work together to forge solutions. Specific assistance<br />

provided was as follows:<br />

• Technical and financial assistance for a national conference of Provincial Council members in March 2005,<br />

convened by the president of Afghanistan. ALGAP worked with the Office of Administrative Affairs to<br />

prepare the conference. The project contracted master facilitators for the event and took responsibility for<br />

reproducing conference materials and preparing participant packets. ALGAP contributed financially to the<br />

repair of dormitory facilities for the conference attendees.<br />

• At the request of Provincial Councils, ALGAP provided technical and financial assistance for regional<br />

conferences in which both Provincial Council members and other governance actors participated. These<br />

conferences were planned and conducted in late spring and summer of 2005. The preparation of the<br />

conferences was undertaken by a regional committee that worked with the ALGAP province-based<br />

facilitators.<br />

Provincial exchanges: During the final months of the project, assistance was provided for provincial<br />

exchanges involving Provincial Council members and other provincial governance actors, including local or<br />

tribal elders and mullahs. The Provincial Councils had expressed an interest in these and requested financial<br />

assistance for them.<br />

3.4.2 Civic Education<br />

ALGAP initiated a provincial governance-focused Civic Education Program during the fall of 2006. The<br />

purpose of this program has been to contribute to efforts to foster a social and political environment in which<br />

broad-based participatory governance might grow. As noted above, prior to the election ALGAP carried out<br />

an information and education program designed to create awareness of the Provincial Council Law and the<br />

roles and functions of Provincial Councils.<br />

The ALGAP Civic Education Program following the election has been comprised of four different elements:<br />

10 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

1. Provincial Council roundtable discussions which were organized and broadcast in nearly all provinces.<br />

The purpose of these roundtables was to increase awareness of and familiarity with Provincial Councils<br />

and their roles and functions.<br />

2. A national mobile theater production was<br />

developed and presented to introduce the<br />

concepts of citizen participation and<br />

collaboration with Provincial Councils and<br />

provincial governance actors. A major theme<br />

of the production was that citizen<br />

participation was not only a right, but a<br />

responsibility that could benefit the entire<br />

province and country.<br />

3. A radio and television adaptation of<br />

mobile theater production was made in<br />

both Dari and Pashto. This activity was<br />

undertaken as a direct result of the response<br />

to the mobile theater and to requests that the<br />

production be made available in more<br />

remote areas or in areas where the security<br />

situation made it impossible for the mobile<br />

theater to perform.<br />

4. BBC New Home New Life production.<br />

To reach a larger audience with messages<br />

about provincial governance, ALGAP<br />

contracted with BBC/Afghan Education<br />

Projects (BBC/AEP) to incorporate<br />

provincial governance themes into its<br />

Mobile Theater performance in the provinces.<br />

popular radio drama series “New<br />

Home/New Life”, “People Talk” and “Village Voice” for broadcast throughout Afghanistan from early<br />

May through June 2007. In addition to the radio programs, provincial governance messages are being<br />

depicted in the BBC/AEP monthly cartoon magazine distributed nationally. Depending upon listener and<br />

reader response to the provincial governance themes, BBC/AEP could determine the themes will become<br />

an integral component of the program scripts of the ongoing radio broadcasts and the monthly magazine<br />

productions.<br />

The unifying message in these the civic education activities is that people and organizations can become<br />

involved in provincial decision-making processes. The campaign also introduced the public to means for<br />

becoming involved and to recognize the benefits of such involvement.<br />

3.4.3 Facilitation Development<br />

As ALGAP began to expand its program of assistance to the Provincial Councils, it faced the challenge of<br />

identifying a pool of qualified facilitators and trainers. It rapidly became clear that the project would have to<br />

devote a significant effort to developing its own human resources. The kind of staff ALGAP required simply<br />

was not available.<br />

Thus ALGAP developed a cadre of Afghan facilitators (province-based facilitators or PBFs) located in the<br />

provinces to coordinate or provide technical assistance and to facilitate the development of an active and<br />

inclusive provincial governance process that includes the involvement of the public—individually and through<br />

groups––as well as government officials and staff.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 11<br />

PHOTO COURTESY OF ALGAP PROJECT

With the recruitment of the field and headquarters staff it was necessary to undertake and maintain a program<br />

of skill enhancement to enable staff members to be able to fulfill their responsibilities. In addition, as part of<br />

the facilitation development process, ALGAP organized training of trainers sessions to orient PBFs to new<br />

workshop modules as they were developed. Three international training consultants worked with the<br />

facilitators and ALGAP program associates in designing, reviewing, and revising workshop modules.<br />

12 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

4.0 FINDINGS<br />

As noted earlier in this report, the circumstances in Afghanistan are unusual and fluid. Lessons learned will not<br />

necessarily be applicable to projects in other countries, or even to subsequent projects in Afghanistan. These<br />

lessons are not large building blocks whose weight and shape will contribute greatly to the foundation of other<br />

projects. At best, they will be small stones or even pebbles that the reader may pick up easily and consider for<br />

filling in a possible gap or to contribute to balance or shape in other project structures.<br />

4.1 PROVINCIAL COUNCILS<br />

Prior to, during, and after their election there was much debate and analysis about how the Provincial Councils<br />

could possibly work given their vague mandate and virtually no authority, as well as their lack of resources. The<br />

only specific Provincial Council authority is to elect from their membership one-third of the Meshrano Jirga<br />

(Upper House of National Assembly) 13. All other roles and responsibilities are advisory in nature.<br />

Some experts advocated holding off on electing Councils until a full legal and regulatory framework could be<br />

put in place, and recommended that the government lead a dialogue to clarify in advance the coordinating<br />

mechanisms and roles of the Councils with other subnational governance bodies.<br />

In spite of these expressions of caution, candidates ran, voters voted, and the Councils met. ALGAP provided<br />

support. Some in the government worried that the project was supporting “34 new mouthpieces,” that were<br />

getting involved in local matters and making demands of the government, which had nothing to offer them.<br />

This Lesson Learned Review indicates that those fears have been largely unfounded; many Provincial Councils<br />

are developing the necessary capacities––skills and knowledge––to work with other provincial governance<br />

entities to fulfill their duties and exercise their authorities, although the degree varies depending on the<br />

province.<br />

Taken together, the findings documented here suggest some strong lessons about the positive influence of the<br />

Provincial Councils in particular and recommendations for continued support for the development of<br />

subnational governance in general in Afghanistan.<br />

During the course of this Lessons Learned Review the author has found substantial evidence to show that the<br />

Councils are succeeding in defining a true and meaningful role for themselves in responding to provincial<br />

needs. The sections that follow detail four specific areas in which Provincial Councils are making a tangible<br />

contribution to provincial governance.<br />

4.1.1 Resolve Disputes<br />

This critical service of the Provincial Councils corresponds directly to Article 4 of the Provincial Council Law,<br />

items 3 and 5. Anecdotes and reports of this highly successful role abound among ALGAP project staff as well<br />

as Council members from Nimroz to Takhar. In chilling details, we hear reports corroborated by Councils<br />

themselves of protracted disputes between individuals, families, districts, even provinces. In all cases heard so<br />

13 In this first election, the provincial councils elected two-thirds of the members of the Meshrano Jirga since the district councils have not<br />

been elected and thus could not select one-third.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 13

far, Councils succeed even where such disputes span decades and have defied efforts by the government and<br />

traditional structures to resolve them.<br />

In one instance, a government ministry intended to sell off pasture land over which families in the area held<br />

customary rights to graze livestock. The conflict led to serious threats of violence. The families feeling<br />

threatened with loss of important pasture land called on the Council to make their case with the Ministry<br />

involved. The Ministry dropped its plan.<br />

In another instance, three local commanders were in conflict and came to the Council to help resolve their<br />

dispute, notably because they do not consider the Provincial Council to be “government.” Indeed, we hear a number of<br />

reports of constituents coming to the Council with conflicts precisely because they felt that the Council, being<br />

elected, would be fair and impartial, whereas they feared “government” representatives would not.<br />

ALGAP staff reported the case of a recent and tragic incident in Jalalabad 14 that risked provoking a major<br />

violent uprising. However, the Provincial Council spoke to the community involved and persuaded them not<br />

to respond with violence. While this report is uncorroborated, it is notable that indeed there was no violent<br />

uprising. Also, this kind of Council role is consistent with many other reports; they are seen as a true “bridge”<br />

between the people and the government, an authority whose allegiance is to their constituents, a neutral body<br />

which has the de facto if not de jure power to facilitate and mediate conflicts and to represent their constituents’<br />

interests to the government. In some cases, the Provincial Councils and their members serve as surrogates for<br />

the traditional bodies and elders.<br />

Tribal disputes also are being brought before Councils. One Council even reported incidents of murder being<br />

brought before them for action, suggesting that the Councils are filling a quasi-judicial void. The processes that<br />

Councils use to resolve disputes seem to be 15 traditional ones that draw on respected local elders, mullahs,<br />

ulemas 16, and others to participate in jirgas or shuras or other meetings during which the matters are aired until a<br />

consensus resolution is reached. Specialists in rule of law might argue that this is an extra-legal mechanism that<br />

erodes important development objectives. However, given the absence of a functioning judicial system in many<br />

parts of Afghanistan, the volatility of the country, and the long tradition of local resolution of disputes through<br />

consensus, it would appear that this role is not only valid but critical at this time.<br />

4.1.2 Act as an Oversight Body<br />

Council members express a commitment to and responsibility for monitoring the activities within their<br />

Provinces to protect the interests of the people. This corresponds directly to their legally-defined duties under<br />

Article 4 of the Provincial Council Law. They interpret this to mean they have responsibility to confirm that<br />

the many donor- and government-funded projects active in their area are proceeding as intended. While they<br />

have no authority to act in those instances where they may find cause for complaint, they have a clear role as a<br />

“bridge” between the people and the government.<br />

The oversight function is being linked to the Councils’ communication roles. Some of the Councils are already<br />

taking the initiative to publish newsletters. While these newsletters are few and are targeted toward limited,<br />

often governmental audiences, they are airing problems and issues that need attention. Further, the Councils<br />

have strong links to the Meshrano Jirga and, both formally and informally, are relating problems to them for<br />

possible support or resolution. Many Councils also have good relations with the governor and line ministry<br />

14 In early March 2007 an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) soldier fired on and killed a number of civilians along the Jalalabad<br />

road.<br />

15 This Lessons Learned Review does not pretend to be a systematic research into this question. See Section 1.0 on lessons learned<br />

methodology.<br />

16 Religious scholars.<br />

14 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

epresentatives to whom they can report their findings. There has been a small, but significant number of<br />

Councils requesting technical assistance from ALGAP to work more effectively with mass media to inform<br />

their constituents and to support additional newsletters or other means of disseminating information.<br />

In addition, any private citizen who may have cause for complaint about a project can bring it to the Council’s<br />

attention because he does not consider the Council to be government. In one dispute that somewhat indirectly illustrates<br />

this lesson learned, a donor-funded food-for-work program came under criticism by local participants who<br />

complained that the amount of food was insufficient for the work involved. The Council explained that the<br />

road they were constructing is the balance of the benefit they receive in addition to the food, and taken<br />

together they are receiving fair compensation for their efforts. The project proceeded. The Council, at least in<br />

this case, not only acted to verify the legitimacy of an activity, but defended it from unwarranted resistance and<br />

criticism. There is no other entity that seems to bridge so nicely between “government” and the people.<br />

4.1.3 Are the Voice of the People<br />

One governor explained that Afghanistan’s enemies have powerful propaganda machines that criticize the<br />

government and its allies. As Councils mediate disputes and monitor reconstruction or other activities in their<br />

provinces, they are in a good position to explain to their constituents the facts. They have the trust and<br />

creditability to do so, whereas “government” actors would not.<br />

As noted above, ALGAP’s workshops are including such topics as how to communicate with the public and<br />

how to work with the media. The Councils already have demonstrated the ability to convene meetings based<br />

on more traditional concepts, during which they can listen to and talk to their constituents. Councils convened<br />

gatherings that exceeded 500 people during their consultation tours. These are important opportunities for<br />

informing the general population of progress, as well for allowing them to air concerns and grievances.<br />

4.1.4 Add Local Leadership for Addressing National Issues<br />

During early spring 2007, a few Councils were taking initiatives to assist the fight against poppy production and<br />

to increase security for their provinces. ALGAP is providing, with USAID concurrence, technical and limited<br />

financial support for additional provincial consultations that will focus specifically on poppy production. In<br />

addition, several Councils are seeking assistance in organizing and conducting information-sharing and<br />

awareness-raising seminars or workshops, and in developing their ability to monitor and report the actions of<br />

government with respect to security and poppy production.<br />

4.2 CAPACITY-BUILDING ACTIVITIES<br />

ALGAP has used four main activities through which the Councils could build their capacity to fulfill their roles<br />

and responsibilities: workshops, provincial consultation tours, conferences, and provincial exchanges. All four<br />

types of activity are reported to have been highly effective and valued by the Councils; the consultation tours<br />

seem to be a clear favorite.<br />

The perceived value of the consultations appears to stem from the direct and personal way it introduced the<br />

Councils to their constituents. In addition, the consultations fostered lines of communication and cooperation<br />

between the Council and other subnational governance actors.<br />

Within each of these groups of activities, we identify specific lessons learned. However, for all lessons learned, we feel<br />

compelled (the chief of party [COP] and the author) to emphasize one that specifically relates to building capacity, cutting across all<br />

groups of activities:<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 15

Building capacity in Afghanistan is a long-term endeavor. ALGAP seemed to be in the right place at the<br />

right time to provide specific capacity-building activities that met real needs in a meaningful way. However,<br />

ongoing interactions with the Council and other subnational governance actors indicate unequivocally that any<br />

successes these activities realize, barely scratch the surface of the problem. Helping Councils to master the<br />

most basic skills in analyzing, planning, organizing, coordinating, following through, and a host of others that<br />

we may take for granted, will require continued attention, support, and exercise.<br />

It is hard to fully appreciate the challenges the Provincial Council members face as individuals as well as teams.<br />

Much of the Afghan society is illiterate, as are many Council members. Even those who have university<br />

educations often lack practical experience working within any sort of business or organization. Keeping<br />

records of their decisions, drafting a letter from the Council, filing correspondence in a way that makes it easy<br />

to retrieve, and responding formally to inquiries and requests for help, are all examples of activities for which<br />

Councils must develop procedures and abilities without any precedent or foundation.<br />

4.2.1 Lessons from Workshops<br />

Provide participants with hands-on training. Workshops began in November 2005 with a basic orientation,<br />

and then evolved to address other topics of immediate relevance. The initial workshop was an orientation to the<br />

law regarding the Provincial Council and its roles and responsibilities as described by the law. ALGAP<br />

developed and conducted the workshop with little direct substantive comment from Provincial Council<br />

members who had just been elected. Subsequent workshops, however, were developed with input from the<br />

province-based facilitators (PBFs) based on direct observations of the Councils. ALGAP staff also met with<br />

small groups of PBFs and Council members to discuss specific modules as these were being developed.<br />

Participation and interest remained high. Admittedly, ALGAP technical staff remained actively engaged to help<br />

identify possible topics of relevance, as participants were in a position of “not knowing what they didn’t<br />

know.”<br />

As time passed, provincial councilors and other workshop participants accepted increasing responsibility for<br />

identifying workshop topics. Some special focus topics included security, anti-corruption, violence against<br />

women, eliminating poppy production, and writing concept papers and proposals. Council members also<br />

identified English language and computer literacy as important topics for building their capacities.<br />

Participatory format works? ARD has developed and used Advanced Participatory Methods (APM)<br />

worldwide in many circumstances and finds it to be a universally effective workshop approach. Some<br />

questioned whether APM would be acceptable in a culture characterized by a conservative perspective or<br />

unaccustomed to a more informal and interactive style of group work. Indeed, these techniques are radically<br />

new in most Afghan contexts but proved popular according to ALGAP’s Afghan staff, as measured by the<br />

feedback as well as the commitment of some, if not all, workshop participants. In balance, it takes a long time<br />

and constant reinforcement, coaching, and mentoring before facilitators can use these methods effectively.<br />

Results with APM are generally better when two or three facilitators can work in a team. Because these<br />

conditions (time, mentoring, facilitator teams) were not always available, it is difficult to determine how well<br />

PBFs were able to fully master and deploy APM techniques in their work with the Provincial Councils.<br />

Multiple-day events are feasible and effective. As workshops were developed and scheduled, an emphasis<br />

was given to one-day events. In part this was due to travel and security concerns as well as an attempt to<br />

recognize constraints on women traveling in some provinces. However, the tendency toward one-day<br />

workshops stemmed in part from comments from Provincial Council members that long-term workshops<br />

created a hardship for them since they had other work to do. Further, their schedules were frequently<br />

interrupted by calls from the government for meetings in Kabul. Over time it became clear that slightly longer<br />

workshops were likely to have greater learning impact. It is also possible that one-day workshops could be<br />

conducted at more frequent intervals.<br />

16 <strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW

4.2.2 Consultation Tours, Possibly the Most Important Activity<br />

Rural Afghanistan often lacks electricity, radio, and telephone, and its population is at least partly illiterate. For<br />

the Councils to serve as a bridge from the people to the government, face-to-face contact is important. Indeed,<br />

this one activity seems almost universally to be the top priority for Councils, and support for their continuation<br />

is emphasized. ALGAP’s support for consultation tours emphasized technical assistance in planning them.<br />

Financial support to cover travel-related expenses is also necessary, in the absence of any operating budget<br />

from the government.<br />

From the first tours, the Provincial Council members and provincial governance participants ascertained that<br />

the information gathered during the trips needed to be shared with authorities responsible for provincial<br />

planning. Reports from the consultation tours indicate that in many instances, councilors did in fact transmit<br />

requests or needs from districts or villages visited to the appropriate line ministry offices within the province<br />

for action. In some isolated cases the Provincial Council members also reported that they followed up the<br />

requests to the ministerial level in Kabul. Thus the consultations had some real benefit for the people and for<br />

the government.<br />

Reports from the field indicate that a major value of the consultations was that they brought attention to<br />

remote areas that few, if any, government or other officials had previously visited. This was a recurring<br />

comment reported by participants in the consultations.<br />

4.2.3 Conferences and Provincial Exchanges; Sometimes “Conferring” is Enough<br />

With ALGAP’s support, the Provincial Councils met both regionally and nationally. Afghanistan’s provinces<br />

have widely varying subcultures, norms, and language differences. Dari and Pashto are the dominant languages,<br />

and also define two populations that compete for attention and authority.<br />

These initial conferences may have helped to bridge some of these barriers and to establish solidarity and sense<br />

of common purpose among the Provincial Councils. The objectives and agendas for the conferences were not<br />

always action-oriented. However, all the participants felt these conferences were extremely important and they<br />

took an active part in them.<br />

Provincial Councils continue to request support for such conferences, and ALGAP has increasingly pressed<br />

for more specific conference objectives and action-oriented agendas. ALGAP is encouraging the Councils to<br />

apply techniques learned from the popular Meeting Management and the Action Planning workshops as they<br />

organize and conduct provincial and regional meetings.<br />

Nevertheless, we must recognize that to some degree, in this culture and environment, just meeting provides<br />

significant benefits to Councils in establishing lines of communication, mutual respect, and trust. What is<br />

agreed upon may be less important than establishing the process of communication.<br />

4.3 CIVIC EDUCATION ACTIVITIES<br />

The ALGAP civic education campaign used a variety of activities that had already proven successful in<br />

Afghanistan. Reputable research institutions had used roundtable discussions and focus groups to illuminate<br />

public opinion. The Election Commission had used mobile theater productions to promote the elections as<br />

well as to inform the population. Radio and TV remain among the most cost-effective means for reaching<br />

broad segments of the population, although remote areas may not have access to them. Print media still has a<br />

place, even among a significantly illiterate population.<br />

<strong>AFGHANISTAN</strong> LOCAL GOVERNANCE ASSISTANCE PROJECT (ALGAP)––LESSONS LEARNED REVIEW 17

4.3.1 Roundtables: Radio and TV Require Special Formats<br />

ALGAP contracted with an Afghan NGO, the Foundation for Culture and Civil Society (FCCS), to conduct<br />

and record roundtable discussions in the provinces and then edit them for 30-minute radio broadcasts. While<br />

FCCS had extensive experience conducting roundtable discussions, it had limited experience conducting them<br />

specifically for broadcast over radio and TV. Several difficulties were encountered. Facilities in the provinces<br />

where the events were held were rudimentary. In some instances, local roundtable hosts lacked adequate<br />