AD 2015 Q4

This is the “not do” component. It is also somewhat harder to define. After all, who determines the duty to care and the non-compliance thereto in unique emergency situations? Still, this component is more likely to lead to a recovery of damages. Put differently, when you are under a legal duty to take reasonable care and you do not do it, then you could be held liable for damages that are directly caused by the breach of that duty. The key elements are “reasonable care” and “directly caused”. Let’s break that down, starting with directly caused. This means that the damages are linked directly to the failure to perform the reasonable duty. This is called a causal connection. In other words, there must be a connection between the duty not complied with and the damages. deep diving are so hazardous that it may well be better to only jeopardise the life of one individual rather than two. That is, of course, as long as no one is put at risk during the subsequent body recovery or rescue efforts! Well, as a qualified instructor and dive leader, I shall continue to teach and advocate the buddy system. I do not like the idea of diving alone anyway. I prefer to share the joys of diving with someone able to share the memories of the dive. To me, diving is, and remains, a team sport. Which introduces another consideration: How would the principle of duty to take care be applied to children who dive? Training agencies impose age and depth restrictions on children who enter the sport before the age of 14. Depending on the age and diving course, a child may be required to dive with an instructor or at least another adult dive buddy. If the adult were to get into trouble, the child would not be expected to meet the duty of care of another adult. He/she would be held to an age appropriate standard. What about all those waivers? As mentioned in the previous article, waivers define the boundaries of the self-imposed risk divers are willing to take by requiring that they acknowledge them. Waivers do not remove all the potential claims for negligence and non-compliance with a duty of care. As such, it is left to our courts to ultimately interpret the content of a waiver within the actual context of damage or injury.

This is the “not do” component. It is also somewhat harder to define. After all, who determines the duty to care and the non-compliance thereto in unique emergency situations? Still, this component is more likely to lead to a recovery of damages. Put differently, when you are under a legal duty to take reasonable care and you do not do it, then you could be held liable for damages that are directly caused by the breach of that duty. The key elements are “reasonable care” and “directly caused”. Let’s break that down, starting with directly caused. This means that the damages are linked directly to the failure to perform the reasonable duty. This is called a causal connection. In other words, there must be a connection between the duty not complied with and the damages.

deep diving are so hazardous that it may well be better to only jeopardise the life of one individual rather than two. That is, of course, as long as no one is put at risk during the subsequent body recovery or rescue efforts! Well, as a qualified instructor and dive leader, I shall continue to teach and advocate the buddy system. I do not like the idea of diving alone anyway. I prefer to share the joys of diving with someone able to share the memories of the dive. To me, diving is, and remains, a team sport. Which introduces another consideration: How would the principle of duty to take care be applied to children who dive? Training agencies impose age and depth restrictions on children who enter the sport before the age of 14. Depending on the age and diving course, a child may be required to dive with an instructor or at least another adult dive buddy. If the adult were to get into trouble, the child would not be expected to meet the duty of care of another adult. He/she would be held to an age appropriate standard. What about all those waivers? As mentioned in the previous article, waivers define the boundaries of the self-imposed risk divers are willing to take by requiring that they acknowledge them. Waivers do not remove all the potential claims for negligence and non-compliance with a duty of care. As such, it is left to our courts to ultimately interpret the content of a waiver within the actual context of damage or injury.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

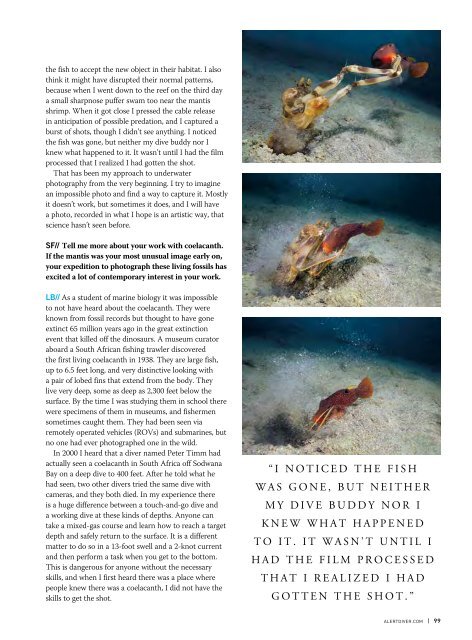

the fish to accept the new object in their habitat. I also<br />

think it might have disrupted their normal patterns,<br />

because when I went down to the reef on the third day<br />

a small sharpnose puffer swam too near the mantis<br />

shrimp. When it got close I pressed the cable release<br />

in anticipation of possible predation, and I captured a<br />

burst of shots, though I didn’t see anything. I noticed<br />

the fish was gone, but neither my dive buddy nor I<br />

knew what happened to it. It wasn’t until I had the film<br />

processed that I realized I had gotten the shot.<br />

That has been my approach to underwater<br />

photography from the very beginning. I try to imagine<br />

an impossible photo and find a way to capture it. Mostly<br />

it doesn’t work, but sometimes it does, and I will have<br />

a photo, recorded in what I hope is an artistic way, that<br />

science hasn’t seen before.<br />

SF// Tell me more about your work with coelacanth.<br />

If the mantis was your most unusual image early on,<br />

your expedition to photograph these living fossils has<br />

excited a lot of contemporary interest in your work.<br />

LB// As a student of marine biology it was impossible<br />

to not have heard about the coelacanth. They were<br />

known from fossil records but thought to have gone<br />

extinct 65 million years ago in the great extinction<br />

event that killed off the dinosaurs. A museum curator<br />

aboard a South African fishing trawler discovered<br />

the first living coelacanth in 1938. They are large fish,<br />

up to 6.5 feet long, and very distinctive looking with<br />

a pair of lobed fins that extend from the body. They<br />

live very deep, some as deep as 2,300 feet below the<br />

surface. By the time I was studying them in school there<br />

were specimens of them in museums, and fishermen<br />

sometimes caught them. They had been seen via<br />

remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and submarines, but<br />

no one had ever photographed one in the wild.<br />

In 2000 I heard that a diver named Peter Timm had<br />

actually seen a coelacanth in South Africa off Sodwana<br />

Bay on a deep dive to 400 feet. After he told what he<br />

had seen, two other divers tried the same dive with<br />

cameras, and they both died. In my experience there<br />

is a huge difference between a touch-and-go dive and<br />

a working dive at these kinds of depths. Anyone can<br />

take a mixed-gas course and learn how to reach a target<br />

depth and safely return to the surface. It is a different<br />

matter to do so in a 13-foot swell and a 2-knot current<br />

and then perform a task when you get to the bottom.<br />

This is dangerous for anyone without the necessary<br />

skills, and when I first heard there was a place where<br />

people knew there was a coelacanth, I did not have the<br />

skills to get the shot.<br />

“I NOTICED THE FISH<br />

WAS GONE, BUT NEITHER<br />

MY DIVE BUDDY NOR I<br />

KNEW WHAT HAPPENED<br />

TO IT. IT WASN’T UNTIL I<br />

H<strong>AD</strong> THE FILM PROCESSED<br />

THAT I REALIZED I H<strong>AD</strong><br />

GOTTEN THE SHOT.”<br />

ALERTDIVER.COM | 99