AD 2015 Q4

This is the “not do” component. It is also somewhat harder to define. After all, who determines the duty to care and the non-compliance thereto in unique emergency situations? Still, this component is more likely to lead to a recovery of damages. Put differently, when you are under a legal duty to take reasonable care and you do not do it, then you could be held liable for damages that are directly caused by the breach of that duty. The key elements are “reasonable care” and “directly caused”. Let’s break that down, starting with directly caused. This means that the damages are linked directly to the failure to perform the reasonable duty. This is called a causal connection. In other words, there must be a connection between the duty not complied with and the damages. deep diving are so hazardous that it may well be better to only jeopardise the life of one individual rather than two. That is, of course, as long as no one is put at risk during the subsequent body recovery or rescue efforts! Well, as a qualified instructor and dive leader, I shall continue to teach and advocate the buddy system. I do not like the idea of diving alone anyway. I prefer to share the joys of diving with someone able to share the memories of the dive. To me, diving is, and remains, a team sport. Which introduces another consideration: How would the principle of duty to take care be applied to children who dive? Training agencies impose age and depth restrictions on children who enter the sport before the age of 14. Depending on the age and diving course, a child may be required to dive with an instructor or at least another adult dive buddy. If the adult were to get into trouble, the child would not be expected to meet the duty of care of another adult. He/she would be held to an age appropriate standard. What about all those waivers? As mentioned in the previous article, waivers define the boundaries of the self-imposed risk divers are willing to take by requiring that they acknowledge them. Waivers do not remove all the potential claims for negligence and non-compliance with a duty of care. As such, it is left to our courts to ultimately interpret the content of a waiver within the actual context of damage or injury.

This is the “not do” component. It is also somewhat harder to define. After all, who determines the duty to care and the non-compliance thereto in unique emergency situations? Still, this component is more likely to lead to a recovery of damages. Put differently, when you are under a legal duty to take reasonable care and you do not do it, then you could be held liable for damages that are directly caused by the breach of that duty. The key elements are “reasonable care” and “directly caused”. Let’s break that down, starting with directly caused. This means that the damages are linked directly to the failure to perform the reasonable duty. This is called a causal connection. In other words, there must be a connection between the duty not complied with and the damages.

deep diving are so hazardous that it may well be better to only jeopardise the life of one individual rather than two. That is, of course, as long as no one is put at risk during the subsequent body recovery or rescue efforts! Well, as a qualified instructor and dive leader, I shall continue to teach and advocate the buddy system. I do not like the idea of diving alone anyway. I prefer to share the joys of diving with someone able to share the memories of the dive. To me, diving is, and remains, a team sport. Which introduces another consideration: How would the principle of duty to take care be applied to children who dive? Training agencies impose age and depth restrictions on children who enter the sport before the age of 14. Depending on the age and diving course, a child may be required to dive with an instructor or at least another adult dive buddy. If the adult were to get into trouble, the child would not be expected to meet the duty of care of another adult. He/she would be held to an age appropriate standard. What about all those waivers? As mentioned in the previous article, waivers define the boundaries of the self-imposed risk divers are willing to take by requiring that they acknowledge them. Waivers do not remove all the potential claims for negligence and non-compliance with a duty of care. As such, it is left to our courts to ultimately interpret the content of a waiver within the actual context of damage or injury.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

underneath us.<br />

He squeezes in<br />

one more name<br />

and hands me<br />

the slate: bastard<br />

trumpeter. I burst<br />

out laughing.<br />

Back on<br />

board, I seek<br />

confirmation on the last sighting. Baron affirms, “Sure<br />

enough, bastard trumpeters. We also have real bastard<br />

trumpeters. Different species.” I start laughing all<br />

over again. Australians have a way with the English<br />

language, and their panache is quite charming. But<br />

my good humor ebbs when I learn about Tasmania’s<br />

disappearing kelp forests.<br />

Giant kelp used to thrive all along Tassie’s east coast.<br />

Scientists say that 90-95 percent of the forests are now<br />

gone, the amazing algae a victim of warming oceans.<br />

Wintertime temperatures used to average 50°F; today<br />

we measured 57°F. The southward-flowing tropical<br />

East Australian Current (the underwater highway<br />

Nemo rode to Hollywood fame), which historically<br />

veered east when it passed Sydney, is now pushing<br />

farther south, warming Tasmanian waters. This spike<br />

in temperature has caused sea urchin populations<br />

to boom, and they’re feeding on kelp nonstop, yearround.<br />

The forests are being clear-cut. The last<br />

holdfasts for Macrocystis pyrifera along the Tasman<br />

Peninsula are in Fortescue Bay and Munro Bight. With<br />

no guarantee they will still be here in 10 or 20 years,<br />

the time for kelp fans to dive Eaglehawk Neck is now.<br />

It’s nearly time for phase two of our expedition, but<br />

before we depart the peninsula for the northern reefs of<br />

Bicheno we dedicate a day to enjoying topside scenery.<br />

We begin with a prebreakfast clifftop hike around<br />

Waterfall Bay for a spectacular bird’s-eye view of some of<br />

our dive sites. Farther south, Cape Hauy’s iconic sea-stack<br />

rock formations — the Candlestick, Totem Pole and the<br />

Lanterns — beckon alluringly in the mauve-tinged dawn.<br />

We answer their call, taking a high-speed Zodiac cruise.<br />

Highlights include bow-riding dolphins, sightings of seals<br />

and albatrosses and staring up slack-jawed at imposing<br />

Cape Pillar. This impossibly sheer precipice of columnar<br />

dolerite rises 1,000 feet straight up from the churning sea.<br />

“SPECCY” DIVES IN BICHENO<br />

A three-hour drive north takes us to Bicheno, a cool<br />

seaside town cradled in an idyllic bay. The soaring sea<br />

cliffs and craggy forested slopes of the south have been<br />

replaced by gently rolling hills and a beach of red lichencovered<br />

rock slabs sliding into the sea. This is Tasmania’s<br />

other famed scuba hub. Just a stone’s throw offshore,<br />

Governor Island Marine Reserve contains most of the<br />

area’s top spots, which include deep pinnacles (“bommies”<br />

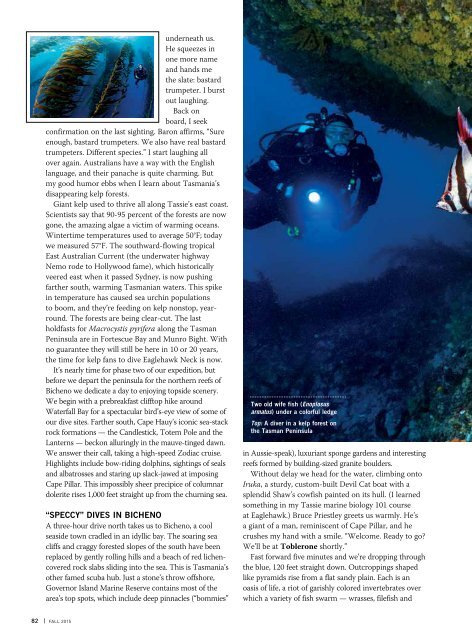

Two old wife fish (Enoplosus<br />

armatus) under a colorful ledge<br />

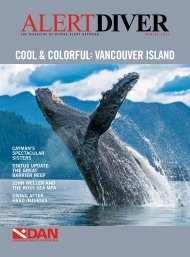

Top: A diver in a kelp forest on<br />

the Tasman Peninsula<br />

in Aussie-speak), luxuriant sponge gardens and interesting<br />

reefs formed by building-sized granite boulders.<br />

Without delay we head for the water, climbing onto<br />

Iruka, a sturdy, custom-built Devil Cat boat with a<br />

splendid Shaw’s cowfish painted on its hull. (I learned<br />

something in my Tassie marine biology 101 course<br />

at Eaglehawk.) Bruce Priestley greets us warmly. He’s<br />

a giant of a man, reminiscent of Cape Pillar, and he<br />

crushes my hand with a smile. “Welcome. Ready to go?<br />

We’ll be at Toblerone shortly.”<br />

Fast forward five minutes and we’re dropping through<br />

the blue, 120 feet straight down. Outcroppings shaped<br />

like pyramids rise from a flat sandy plain. Each is an<br />

oasis of life, a riot of garishly colored invertebrates over<br />

which a variety of fish swarm — wrasses, filefish and<br />

82 | FALL <strong>2015</strong>