15082018 - FIRST LADY OTHERS SHINE AT VANGUARD AWARDS

Vanguard Newspaper 15 April 2018

Vanguard Newspaper 15 April 2018

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

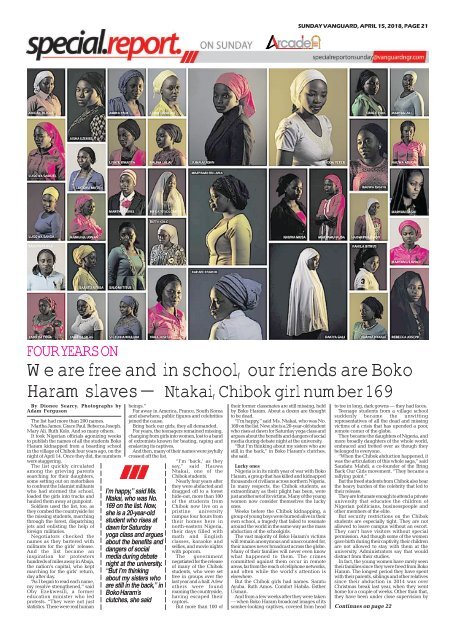

SUNDAY <strong>VANGUARD</strong>, APRIL 15, 2018, PAGE 21<br />

FOUR YEARS ON<br />

We are free and in school, our friends are Boko<br />

Haram slaves — Ntakai, Chibok girl number 169<br />

By Dionee Searcy. Photographs by<br />

Adam Ferguson<br />

The list had more than 200 names.<br />

Martha James. Grace Paul. Rebecca Joseph.<br />

Mary Ali. Ruth Kolo. And so many others.<br />

It took Nigerian officials agonizing weeks<br />

to publish the names of all the students Boko<br />

Haram kidnapped from a boarding school<br />

in the village of Chibok four years ago, on the<br />

night of April 14. Once they did, the numbers<br />

were staggering.<br />

The list quickly circulated<br />

among the grieving parents<br />

searching for their daughters,<br />

some setting out on motorbikes<br />

to confront the Islamist militants<br />

who had stormed the school,<br />

loaded the girls into trucks and<br />

hauled them away at gunpoint.<br />

Soldiers used the list, too, as<br />

they combed the countryside for<br />

the missing students, marching<br />

through the forest, dispatching<br />

jets and enlisting the help of<br />

foreign militaries.<br />

Negotiators checked the<br />

names as they bartered with<br />

militants for the girls’ release.<br />

And the list became an<br />

inspiration for protesters<br />

hundreds of miles away in Abuja,<br />

the nation’s capital, who kept<br />

marching for the girls’ return,<br />

day after day.<br />

“As I began to read each name,<br />

my resolve strengthened,” said<br />

Oby Ezekwesili, a former<br />

education minister who led<br />

protests. “They were not just<br />

statistics. These were real human<br />

beings.”<br />

Far away in America, France, South Korea<br />

and elsewhere, public figures and celebrities<br />

joined the cause.<br />

Bring back our girls, they all demanded.<br />

For years, the teenagers remained missing,<br />

changing from girls into women, lost to a band<br />

of extremists known for beating, raping and<br />

enslaving its captives.<br />

And then, many of their names were joyfully<br />

crossed off the list.<br />

“I’m ‘back,’ as they<br />

say,” said Hauwa<br />

Ntakai, one of the<br />

Chibok students.<br />

Nearly four years after<br />

I’m happy,” said Ms.<br />

Ntakai, who was No.<br />

169 on the list. Now,<br />

she is a 20-year-old<br />

student who rises at<br />

dawn for Saturday<br />

yoga class and argues<br />

about the benefits and<br />

dangers of social<br />

media during debate<br />

night at the university.<br />

“But I’m thinking<br />

about my sisters who<br />

are still in the back,” in<br />

Boko Haram’s<br />

clutches, she said<br />

they were abducted and<br />

dragged off to a forest<br />

hide-out, more than 100<br />

of the students from<br />

Chibok now live on a<br />

pristine university<br />

campus four hours from<br />

their homes here in<br />

north-eastern Nigeria,<br />

their days filled with<br />

math and English<br />

classes, karaoke and<br />

selfies, and movie nights<br />

with popcorn.<br />

The government<br />

negotiated for the release<br />

of many of the Chibok<br />

students, who were set<br />

free in groups over the<br />

last year and a half. A few<br />

others were found<br />

roaming the countryside,<br />

having escaped their<br />

captors.<br />

But more than 100 of<br />

their former classmates are still missing, held<br />

by Boko Haram. About a dozen are thought<br />

to be dead.<br />

“I’m happy,” said Ms. Ntakai, who was No.<br />

169 on the list. Now, she is a 20-year-old student<br />

who rises at dawn for Saturday yoga class and<br />

argues about the benefits and dangers of social<br />

media during debate night at the university.<br />

“But I’m thinking about my sisters who are<br />

still in the back,” in Boko Haram’s clutches,<br />

she said.<br />

Lucky ones<br />

Nigeria is in its ninth year of war with Boko<br />

Haram, a group that has killed and kidnapped<br />

thousands of civilians across northern Nigeria.<br />

In many respects, the Chibok students, as<br />

extraordinary as their plight has been, were<br />

just another set of its victims. Many of the young<br />

women now consider themselves the lucky<br />

ones.<br />

Weeks before the Chibok kidnapping, a<br />

group of young boys were burned alive in their<br />

own school, a tragedy that failed to resonate<br />

around the world in the same way as the mass<br />

abduction of the schoolgirls.<br />

The vast majority of Boko Haram’s victims<br />

will remain anonymous and unaccounted for,<br />

their names never broadcast across the globe.<br />

Many of their families will never even know<br />

what happened to them. The crimes<br />

committed against them occur in remote<br />

areas, far from the reach of cellphone networks,<br />

and often while the world’s attention is<br />

elsewhere.<br />

But the Chibok girls had names. Saratu<br />

Ayuba. Ruth Amos. Comfort Habila. Esther<br />

Usman.<br />

And from a few weeks after they were taken<br />

— when Boko Haram broadcast images of its<br />

somber-looking captives, covered from head<br />

to toe in long, dark gowns — they had faces.<br />

Teenage students from a village school<br />

suddenly became the unwitting<br />

representatives of all the dead and missing<br />

victims of a crisis that has upended a poor,<br />

remote corner of the globe.<br />

They became the daughters of Nigeria, and<br />

more broadly daughters of the whole world,<br />

embraced and fretted over as though they<br />

belonged to everyone.<br />

“When the Chibok abduction happened, it<br />

was the articulation of this whole saga,” said<br />

Saudatu Mahdi, a co-founder of the Bring<br />

Back Our Girls movement. “They became a<br />

rallying point.”<br />

But the freed students from Chibok also bear<br />

the heavy burden of the celebrity that led to<br />

their release.<br />

They are fortunate enough to attend a private<br />

university that educates the children of<br />

Nigerian politicians, businesspeople and<br />

other members of the elite.<br />

But security restrictions on the Chibok<br />

students are especially tight. They are not<br />

allowed to leave campus without an escort.<br />

They can’t have visitors without special<br />

permission. And though some of the women<br />

gave birth during their captivity, their children<br />

are not allowed to stay with them at the<br />

university. Administrators say that would<br />

distract from their studies.<br />

In fact, the young women have rarely seen<br />

their families since they were freed from Boko<br />

Haram. The longest period they have spent<br />

with their parents, siblings and other relatives<br />

since their abduction in 2014 was over<br />

Christmas break last year, when they went<br />

home for a couple of weeks. Other than that,<br />

they have been under close supervision by<br />

Continues on page 22