Issue 90 / July 2018

July 2018 issue of Bido Lito! magazine. Featuring: MC NELSON, THE DSM IV, GRIME OF THE EARTH, EMEL MATHLOUTHI, REMY JUDE, LIVERPOOL BIENNIAL, CAR SEAT HEADREST, THE MYSTERINES, TATE @ 30 and much more.

July 2018 issue of Bido Lito! magazine. Featuring: MC NELSON, THE DSM IV, GRIME OF THE EARTH, EMEL MATHLOUTHI, REMY JUDE, LIVERPOOL BIENNIAL, CAR SEAT HEADREST, THE MYSTERINES, TATE @ 30 and much more.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

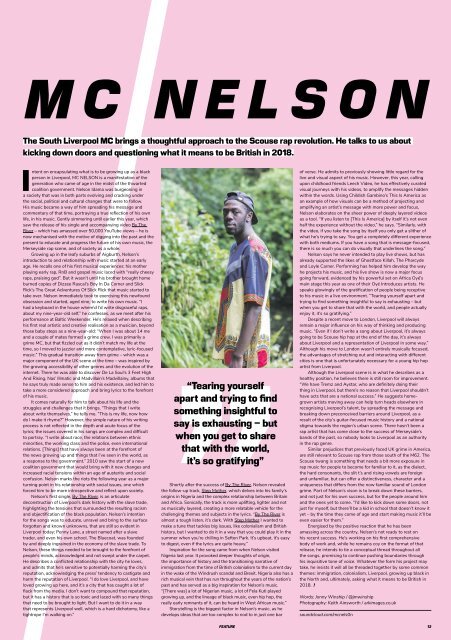

MC NELSON<br />

The South Liverpool MC brings a thoughtful approach to the Scouse rap revolution. He talks to us about<br />

kicking down doors and questioning what it means to be British in <strong>2018</strong>.<br />

Intent on encapsulating what is to be growing up as a black<br />

person in Liverpool, MC NELSON is a manifestation of the<br />

generation who came of age in the midst of the thwarted<br />

coalition government. Nelson Idama was burgeoning in<br />

a society that was in both parts evolving and cracking under<br />

the social, political and cultural changes that were to follow.<br />

His music became a way of him spreading his message and<br />

commentary of that time, portraying a true reflection of his own<br />

life, in his music. Gently simmering until earlier this year, which<br />

saw the release of his single and accompanying video By The<br />

River – which has amassed over 50,000 YouTube views – he is<br />

now mechanised with the motive of digging into the past and the<br />

present to educate and progress the future of his own music, the<br />

Merseyside rap scene, and of society as a whole.<br />

Growing up in the leafy suburbs of Aigburth, Nelson’s<br />

introduction to and relationship with music started at an early<br />

age. He recalls one of his first musical experiences: his mother<br />

playing early rap, RnB and gospel music laced with “really cheesy<br />

raps, praising god”. But it wasn’t until his brother brought home<br />

burned copies of Dizzee Rascal’s Boy In Da Corner and Slick<br />

Rick’s The Great Adventures Of Slick Rick that music started to<br />

take over. Nelson immediately took to exercising this newfound<br />

obsession and started, aged nine, to write his own music. “I<br />

had a keyboard in the house where’d I’d write disgraceful raps,<br />

about my nine-year-old self,” he confesses, as we meet after his<br />

performance at Baltic Weekender. He’s relaxed when describing<br />

his first real artistic and creative realisation as a musician, beyond<br />

those baby steps as a nine-year-old: “When I was about 14 me<br />

and a couple of mates formed a grime crew. I was primarily a<br />

grime MC, but that fizzled out as it didn’t match my life at the<br />

time, so I moved to jazzier and more contemplative, lyric-focused<br />

music.” This gradual transition away from grime – which was a<br />

major component of the UK scene at the time – was inspired by<br />

the growing accessibility of other genres and the evolution of the<br />

internet. There he was able to discover De La Soul’s 3 Feet High<br />

And Rising, Nas’ Illmatic and Madvillain’s Madvillainy, albums that<br />

he says truly made sense to him and his existence, and led him to<br />

take a more considered approach and bring lyrics to the forefront<br />

of his music.<br />

It comes naturally for him to talk about his life and the<br />

struggles and challenges that it brings. “Things that I write<br />

about write themselves,” he tells me. “This is my life, now how<br />

do I make it rhyme?” However, the simple nature of his writing<br />

process is not reflected in the depth and acute focus of the<br />

lyrics; the issues covered in his songs are complex and difficult<br />

to portray. “I write about race, the relations between ethnic<br />

minorities, the working class and the police, even international<br />

relations. [Things] that have always been at the forefront of<br />

the news growing up and things that I’ve seen in the world, as<br />

a response to the government.” 2010 saw the start of a new<br />

coalition government that would bring with it new changes and<br />

increased racial tensions within an age of austerity and social<br />

confusion. Nelson marks the riots the following year as a major<br />

turning point in his relationship with social issues, one which<br />

forced him to be more introspective and reflect upon society.<br />

Nelson’s first single, By The River, is an articulate<br />

deconstruction of Liverpool’s dark history with the slave trade,<br />

highlighting the tensions that surrounded the resulting racism<br />

and objectification of the black population. Nelson’s intention<br />

for the songs was to educate, unravel and bring to the surface<br />

forgotten and known unknowns, that are still so evident in<br />

Liverpool today; Penny Lane, a street named after a slave<br />

trader, and even his own school, The Bluecoat, was founded<br />

by and deeply ingrained in the economy of the slave trade. To<br />

Nelson, these things needed to be brought to the forefront of<br />

people’s minds, acknowledged and not swept under the carpet.<br />

He describes a conflicted relationship with the city he loves,<br />

and admits that he’s sensitive to potentially harming the city’s<br />

reputation, acknowledging the press’ tendency to castigate and<br />

harm the reputation of Liverpool. “I do love Liverpool, and have<br />

loved growing up here, and it’s a city that has caught a lot of<br />

flack from the media. I don’t want to compound that reputation,<br />

but it has a history that is so toxic and laced with so many things<br />

that need to be brought to light. But I want to do it in a way<br />

that represents Liverpool well, which is a hard dichotomy, like a<br />

tightrope I’m walking on.”<br />

“Tearing yourself<br />

apart and trying to find<br />

something insightful to<br />

say is exhausting – but<br />

when you get to share<br />

that with the world,<br />

it’s so gratifying”<br />

Shortly after the success of By The River, Nelson revealed<br />

the follow-up track, Step Mother, which delves into his family’s<br />

origins in Nigeria and the complex relationship between Britain<br />

and Africa. Sonically, the track is more uplifting, lighter and not<br />

as musically layered, creating a more relatable vehicle for the<br />

challenging themes and subjects in the lyrics. “By The River is<br />

almost a tough listen, it’s dark. With Step Mother I wanted to<br />

make a tune that tackles big issues, like colonialism and British<br />

history, but I wanted to do it in a way that you could play it in the<br />

summer when you’re chilling in Sefton Park. It’s upbeat, it’s easy<br />

to digest, even if the lyrics are quite heavy.”<br />

Inspiration for the song came from when Nelson visited<br />

Nigeria last year. It provoked deeper thoughts of origin,<br />

the importance of history and the transitioning narrative of<br />

immigration from the time of British colonialism to the current day<br />

in the wake of the Windrush scandal and Brexit. Nigeria also has a<br />

rich musical vein that has run throughout the years of the nation’s<br />

past and has served as a big inspiration for Nelson’s music.<br />

“[There was] a lot of Nigerian music, a lot of Fela Kuti played<br />

growing up, and the lineage of black music, even hip hop, the<br />

really early remnants of it, can be heard in West African music.”<br />

Storytelling is the biggest factor in Nelson’s music, as he<br />

develops ideas that are too complex to nod to in just one bar<br />

of verse. He admits to previously showing little regard for the<br />

live and visual aspect of his music. However, this year, calling<br />

upon childhood friends Leech Video, he has effectively curated<br />

visual journeys with his videos, to amplify the messages hidden<br />

within the words. Using Childish Gambino’s This Is America as<br />

an example of how visuals can be a method of projecting and<br />

amplifying an artist’s message with more power and focus,<br />

Nelson elaborates on the sheer power of deeply layered videos<br />

as a tool. “If you listen to [This Is America] by itself it’s not even<br />

half the experience without the video,” he says. “Similarly, with<br />

the video, if you take the song by itself you only get a slither of<br />

what he’s trying to say. You get a completely different experience<br />

with both mediums. If you have a song that is message-focused,<br />

there is so much you can do visually that underlines the song.”<br />

Nelson says he never intended to play live shows, but has<br />

already supported the likes of Ghostface Killah, The Pharcyde<br />

and Loyle Carner. Performing has helped him develop the way<br />

he projects his music, and his live show is now a major focus<br />

going forward, evidenced by his powerful set on Africa Oyé’s<br />

main stage this year as one of their Oyé Introduces artists. He<br />

speaks glowingly of the gratification of people being receptive<br />

to his music in a live environment. “Tearing yourself apart and<br />

trying to find something insightful to say is exhausting – but<br />

when you get to share that with the world, and people actually<br />

enjoy it, it’s so gratifying.”<br />

Despite a recent move to London, Liverpool will always<br />

remain a major influence on his way of thinking and producing<br />

music. “Even if I don’t write a song about Liverpool, it’s always<br />

going to be Scouse hip hop at the end of the day, it’s always<br />

about Liverpool and a representation of Liverpool in some way.”<br />

Although his move to London wasn’t entirely musically focused,<br />

the advantages of stretching out and interacting with different<br />

cities is one that is unfortunately necessary for a young hip hop<br />

artist from Liverpool.<br />

Although the Liverpool scene is in what he describes as a<br />

healthy position, he believes there is still room for improvement.<br />

“We have Tremz and Aystar, who are definitely doing their<br />

thing in Liverpool, but there’s no reason that Liverpool shouldn’t<br />

have acts that are a national success.” He suggests homegrown<br />

artists moving away can help turn heads elsewhere in<br />

recognising Liverpool’s talent, by spreading the message and<br />

breaking down preconceived barriers around Liverpool, as a<br />

result of the city’s guitar-focused music history and a national<br />

stigma towards the region’s urban scene. There hasn’t been a<br />

rap artist that has come close to the success of Merseyside’s<br />

bands of the past, so nobody looks to Liverpool as an authority<br />

in the rap genre.<br />

Similar prejudices that previously faced UK grime in America,<br />

are still relevant to Scouse rap from those south of the M62. The<br />

Scouse twang is something that needs a bit more exposure in<br />

rap music for people to become for familiar to it, as the dialect,<br />

the hard consonants, the slit t’s and rising vowels are foreign<br />

and unfamiliar, but can offer a distinctiveness, character and a<br />

uniqueness that differs from the now familiar sound of London<br />

grime. Part of Nelson’s vison is to break down these barriers,<br />

and not just for his own success, but for the people around him<br />

and the ones yet to come. “I’d like to kick down some doors, not<br />

just for myself, but there’ll be a kid in school that doesn’t know it<br />

yet – by the time they come of age and start making music it’ll be<br />

even easier for them.”<br />

Energised by the positive reaction that he has been<br />

amassing across the country, Nelson’s not ready to rest on<br />

his recent success. He’s working on his first comprehensive<br />

body of work and, while he remains coy on the format of that<br />

release, he intends to tie a conceptual thread throughout all<br />

the songs, promising to continue pushing boundaries through<br />

his inquisitive tone of voice. Whatever the form his project may<br />

take, he insists it will all be threaded together by some common<br />

themes: immigration, colonialism, Liverpool, growing up black in<br />

the North and, ultimately, asking what it means to be British in<br />

<strong>2018</strong>. !<br />

Words: Jonny Winship / @jmwinship<br />

Photography: Keith Ainsworth / arkimages.co.uk<br />

soundcloud.com/mcnels0n<br />

FEATURE<br />

13