cearticle #4 ce test - VetLearn.com

cearticle #4 ce test - VetLearn.com

cearticle #4 ce test - VetLearn.com

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CE<br />

854 Vol. 25, No. 11 November 2003<br />

Article <strong>#4</strong> (1.5 contact hours)<br />

Refereed Peer Review<br />

KEY FACTS<br />

■ Clinical signs of upper airway<br />

obstruction should raise a<br />

clinician’s suspicion for tracheal<br />

neoplasia as a diagnostic<br />

differential.<br />

■ Caution during diagnostics and<br />

therapeutics is needed to<br />

prevent respiratory<br />

embarrassment.<br />

■ Treatment for tracheal tumors<br />

may include surgical removal,<br />

chemotherapy, and/or radiation<br />

therapy, depending on tumor<br />

type and stage.<br />

V<br />

Comments? Questions?<br />

Email: <strong>com</strong>pendium@medimedia.<strong>com</strong><br />

Web: <strong>VetLearn</strong>.<strong>com</strong> • Fax: 800-556-3288<br />

Primary Tracheal Tumors<br />

in Dogs and Cats<br />

Texas A&M University<br />

M. Raquel Brown, DVM, DACVIM (Internal Medicine)<br />

Kenita S. Rogers, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Internal Medicine, Oncology)<br />

ABSTRACT: Primary neoplasms of the trachea are un<strong>com</strong>mon in dogs and cats. Patients are<br />

often middle aged or older, ex<strong>ce</strong>pt dogs with osteochondromas. Clinical signs consistent with<br />

tracheal obstruction, including dyspnea, wheezing, stridor, and cough, are <strong>com</strong>mon. Caution<br />

should be used during diagnostics and therapeutics to prevent respiratory embarrassment.<br />

Survey radiography often reveals the mass, and bronchoscopy allows direct visualization and<br />

sampling of the lesion. Options for treatment include surgical excision, chemotherapy, radiation<br />

therapy, or some <strong>com</strong>bination of these methods. Most tumors respond well to <strong>com</strong>plete surgical<br />

excision, although lymphoma responds best to chemotherapy, with or without adjunctive<br />

radiation therapy. Data on long-term follow-up are not available, but prognosis most likely<br />

depends on tumor type and stage.<br />

Primary neoplasms of the trachea are un<strong>com</strong>mon in animals and humans,<br />

and both benign and malignant tumor types occur. 1–5 Most patients are<br />

older, although young dogs with active osteochondral ossification sites are<br />

at a higher risk of benign tracheal osteochondromas. 5,6 Clinical signs of upper<br />

airway obstruction, including dyspnea, stridor, wheezing, exercise intoleran<strong>ce</strong>,<br />

and cough, should raise the clinician’s suspicion of this problem, and radiography<br />

often supports the diagnosis. 2 Treatment options include surgical removal,<br />

chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and various <strong>com</strong>binations of these modalities.<br />

Treatment re<strong>com</strong>mendations depend on tumor type and staging. Prognosis for<br />

these patients must be considered guarded because long-term follow-up of large<br />

case series has not been reported. Prognosis most likely depends on tumor type. 2<br />

SIGNALMENT<br />

Canine primary tracheal tumors often present in a bimodal age distribution<br />

1,2,6–16 (Table 1). Of the reported ages in the literature, eight dogs were 2<br />

years of age and younger, and 10 were 6 years of age and older, with osteochondroma<br />

and ecchondroma/osteochondromal dysplasia occurring in younger<br />

dogs. 13–16 Both males and females are affected, with various breeds represented<br />

(Table 1).<br />

Cats are often older, with the mean age of reported cases being 9.5 years 1,7–27<br />

(Table 2). Both sexes are represented, with domestic short-haired and Siamese<br />

most <strong>com</strong>monly affected. Of the 19 reported cases of feline tracheal tumors,<br />

feline leukemia virus (FeLV) status was reported in seven cats, and one had<br />

www.<strong>VetLearn</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

Compendium November 2003 Primary Tracheal Tumors in Dogs and Cats 855<br />

Table 1. Reported Primary Tracheal Tumors in Dogs<br />

Age<br />

Study (years) Sex Breed Sign(s) Tumor Type Treatment Out<strong>com</strong>e<br />

Carlisle et al1 12 FS Miniature Cough Adenocarcinoma None Euthanized<br />

poodle Sneeze<br />

Hill et al7 10 M Spitz Dyspnea Carcinoma — —<br />

Harvey and 8 M Siberian Dyspnea Mast <strong>ce</strong>ll tumor Surgery —<br />

Sykes11 husky<br />

Carlisle et al1 13 F German Dyspnea Mast <strong>ce</strong>ll tumor None Euthanized<br />

shepherd Stridor<br />

Bryan et al10 “Aged” F Mix Dyspnea Leiomyoma Surgery Alive after<br />

6 months<br />

Black et al9 10 M Miniature Panting Leiomyoma Surgery Alive after<br />

poodle 7 months<br />

Chaffin et al2 10 FS Mix Dyspnea Extramedullary Surgery Alive after<br />

plasmacytoma 3 months<br />

Brodey et al12 7 F Mix Cough Osteosar<strong>com</strong>a None Euthanized<br />

Carlisle et al1 10 F Collie Dyspnea<br />

Stridor<br />

Chondroma Surgery —<br />

Aron et al8 6 M German Dyspnea Chondrosar<strong>com</strong>a Surgery Alive after<br />

shepherd Cough<br />

Voi<strong>ce</strong> change<br />

12 months<br />

Carlisle et al1 1 FS Doberman Dyspnea Chondrosar<strong>com</strong>a Surgery Alive, but<br />

Stridor metastasis<br />

after 9<br />

months<br />

Hough et al15 0.5 F Labrador Dyspnea Osteochondroma Surgery Alive after<br />

retriever 6 months<br />

Withrow et al6 0.25 M Old Wheeze Osteochondroma Surgery Alive after<br />

English<br />

sheepdog<br />

7 months<br />

Dubielzig and 0.5 — Alaskan Dyspnea Osteochondroma None Died during<br />

Dickey14 malamute diagnostics<br />

Gourley et al16 0.9 F Alaskan Collapse Osteochondroma Surgery Alive after<br />

malamute 8 months<br />

Carlisle et al1 0.5 M German Wheeze Osteochondroma Surgery —<br />

shepherd Cyanosis<br />

Carb and 0.9 M Siberian Dyspnea Ecchondroma Surgery Alive after<br />

Halliwell13 husky (osteochondral<br />

dysplasia)<br />

5 months<br />

Carb and 2 F Mix Dyspnea Ecchondroma Surgery Alive after<br />

Halliwell13 (osteochondral<br />

dysplasia)<br />

1 year<br />

FS = female spayed; dashes indicate unknown data.<br />

www.<strong>VetLearn</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

856 Small Animal/Exotics Compendium November 2003<br />

Table 2. Reported Primary Tracheal Tumors in Cats<br />

Age FeLV/FIV<br />

Study (years) Sex Breed Status Sign(s) Tumor Type Treatment Out<strong>com</strong>e<br />

Brown and 10 FS DLH — Cough Lymphoma Medical Euthanized<br />

Rogers25 Wheeze after 38 days<br />

Brown and 11 CM DSH FeLV–, FIV– Dyspnea Lymphoma Medical Alive after<br />

Rogers25 Radiation 21 months<br />

Brown and 4 CM DSH FeLV–, FIV– Cough Lymphoma Medical Alive after<br />

Rogers25 Wheeze 23 months<br />

Brown and 13 CM DSH FeLV–, FIV– Wheeze Lymphoma Medical Alive after<br />

Rogers25 Cyanosis Radiation 17 months<br />

Schnieder 7 M Siamese FeLV+ Dyspnea Lymphoma Medical Alive after<br />

et al23 Surgical 8 months<br />

Zimmerman 9 M Siamese — Dyspnea Lymphoma Surgical Recurred<br />

et al22 Euthanized<br />

after 10 days<br />

Beaumont17 11 CM DSH FeLV–, FIV– Dyspnea Lymphoma Surgical Systemic after<br />

4 months<br />

Kim et al24 13 FS Siamese FeLV–, FIV– Dyspnea Lymphoma None Euthanized<br />

Beaumont17 11 FS Siamese — Dyspnea Adenocarcinoma None Euthanized<br />

Cain and<br />

Manley<br />

10 — Siamese — Cough Adenocarcinoma Surgical —<br />

19<br />

Evers et al20 12 CM DSH FeLV– Dyspnea Adenocarcinoma Surgical Recurred<br />

Euthanized<br />

after 12<br />

months<br />

Zimmerman 12 M Persian — Dyspnea Adenocarcinoma Surgical Alive after<br />

et al22 Cough 12 months<br />

Evers et al20 12 FS DSH — Dyspnea Adenocarcinoma Surgical Alive after<br />

3 months<br />

Neer and 7 — DLH — Wheeze Adenocarcinoma Surgical Recurred<br />

Zeman18 Dyspnea Euthanized<br />

after 17<br />

months<br />

Carlisle et al1 6 FS Domestic — Stridor Seromucinous<br />

carcinoma<br />

None Euthanized<br />

Glock21 6 — — — Weight<br />

loss<br />

Adenoma None Euthanized<br />

Lobetti and 11 CM DSH — Dyspnea Squamous <strong>ce</strong>ll None Euthanized<br />

Williams26 carcinoma<br />

Carlisle et al1 9 M Domestic — Wheeze Carcinoma Surgical Died after<br />

Dyspnea 15 months<br />

Veith27 2 CM DSH — Dyspnea Squamous <strong>ce</strong>ll<br />

carcinoma<br />

None Died<br />

CM = castrated male; DLH = domestic long-haired; DSH = domestic short-haired; FS = female spayed; dashes indicate unknown data.<br />

www.<strong>VetLearn</strong>.<strong>com</strong>

Compendium November 2003 Primary Tracheal Tumors in Dogs and Cats 857<br />

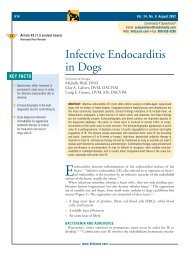

Figure 1—Thoracic radiograph of a cat with intratracheal lymphoma. Note the<br />

multiple masses within the tracheal lumen (arrows). (From Brown MR, Rogers<br />

KS, Mansell KJ, et al: Primary intratracheal lymphosar<strong>com</strong>a in four cats.<br />

JAAHA 39:468–472, 2003; with permission)<br />

positive results on an immunofluores<strong>ce</strong>nt antibody <strong>test</strong>.<br />

Of the five cats <strong>test</strong>ed for feline immunodeficiency<br />

virus (FIV), all had negative results.<br />

HISTORY AND CLINICAL SIGNS<br />

Acute, intermittent, or chronic and progressive signs<br />

of tracheal obstruction may prompt presentation<br />

of the patient to the veterinarian. 28 Dyspnea, wheezing,<br />

exercise intoleran<strong>ce</strong>, and coughing are <strong>com</strong>mon <strong>com</strong>plaints.<br />

2,29 Depression, voi<strong>ce</strong> change, intermittent<br />

cyanosis, inability to bark, collapse, or weight loss may<br />

also be noted. 8,16,21 Although some patients present with<br />

no overt clinical signs, many are in obvious respiratory<br />

distress. Along with the clinical signs already listed,<br />

referred upper airway sounds may be auscultated. 29<br />

Patients may be<strong>com</strong>e cyanotic with the stress of physical<br />

examination. Cats may begin open-mouth breathing<br />

or may present in a crouched stan<strong>ce</strong> with their head<br />

and neck extended. 4 Patients may show a preferen<strong>ce</strong> for<br />

sternal recumbency over lateral recumbency. 4 A 6month-old<br />

Alaskan malamute that presented for osteochondroma<br />

of the trachea had obvious hemorrhage at<br />

the laryngeal opening. 14<br />

DIAGNOSTICS<br />

When the patient’s condition permits, radiography is<br />

the diagnostic pro<strong>ce</strong>dure of choi<strong>ce</strong>. 30 Tracheal tumors are<br />

often dis<strong>ce</strong>rnible on survey radiography because these<br />

masses are outlined by tracheal air, which provides a natural<br />

contrast medium 29 (Figure 1). If tracheal neoplasia is<br />

considered a diagnostic differential and the thoracic radiographs<br />

are within normal limits, radiographs of the<br />

neck should be obtained. Intratracheal masses may present<br />

in a variety of locations within the trachea, from just<br />

www.<strong>VetLearn</strong>.<strong>com</strong><br />

caudal to the larynx to the carina. Overexpansion<br />

of the lungs, flattening of the diaphragm,<br />

and prominent pulmonary vasculature<br />

secondary to increased air content of<br />

the lungs have been noted in cats with<br />

intratracheal tumors. 25 If severe respiratory<br />

embarrassment is present, oxygen therapy<br />

or sedation may be ne<strong>ce</strong>ssary to obtain<br />

diagnostic radiographs without endangering<br />

the patient. 4<br />

Bronchoscopy offers direct visualization<br />

of the mass(es) (Figure 2), unless substantial<br />

hemorrhaging is present. Brush<br />

cytology and biopsies may also be<br />

obtained for evaluation 30 (Figure 3). Brush<br />

cytology offers the clinician the potential<br />

to make an immediate diagnosis and provide<br />

immediate treatment.<br />

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS<br />

Intratracheal mast <strong>ce</strong>ll tumor, 1,11 adenocarcinoma, 1<br />

carcinoma, 7 leiomyoma, 9,10 chondroma, 10 osteosar<strong>com</strong>a,<br />

12 extramedullary plasmacytoma, 2 rhabdomyosar<strong>com</strong>a,<br />

and chondrosar<strong>com</strong>a 1,8 have been reported in<br />

dogs. Five cases of osteochondroma 1,6,14–16 and two cases<br />

of ecchondroma/osteochondromal dysplasia 13 have<br />

been reported in young dogs. These benign tracheal<br />

osteocartilaginous tumors grow in synchrony with the<br />

rest of the musculoskeletal system and, therefore,<br />

should stop growing with skeletal maturity. Intraluminal<br />

adenocarcinoma, 17–22 lymphoma, 17,22–25 squamous<br />

<strong>ce</strong>ll carcinoma, 26,27 and adenoma 21 have been reported<br />

in cats. Intratracheal neoplasms must be differentiated<br />

from nonneoplastic intraluminal masses. Differentials<br />

for nonneoplastic intraluminal masses include polyps, 31<br />

eosinophilic granulomas, 32 nodular amyloidosis, 33 tissue<br />

reaction to Filaroides osleri, 34 chondromatous hamartoma,<br />

35 papillomatosis, 36 and hyperplastic tracheitis of<br />

unknown cause. 37 Stenosis of the tracheal lumen may<br />

be iatrogenically indu<strong>ce</strong>d via ex<strong>ce</strong>ssive inflation of an<br />

endotracheal tube or other trauma. 38,39<br />

STAGING<br />

Ideally, all dogs and cats with neoplasia should<br />

undergo staging before definitive treatment re<strong>com</strong>mendations<br />

are made. 30 Intratracheal neoplasms causing respiratory<br />

<strong>com</strong>promise sometimes present an ex<strong>ce</strong>ption<br />

to this rule because immediate therapy may need to be<br />

initiated. If time permits, clinical pathology and imaging<br />

modalities should be performed. For all animals, a<br />

<strong>com</strong>plete blood <strong>ce</strong>ll count, chemistry profile, and urinalysis<br />

should be conducted. 30 FeLV and FIV status<br />

should be determined in all cats. Thoracic radiographs

858 Small Animal/Exotics Compendium November 2003<br />

Figure 2—Photograph taken during bronchoscopy of a dog<br />

with an intratracheal tumor.<br />

should be evaluated for eviden<strong>ce</strong> of metastasis. Abdominal<br />

ultrasonography allows evaluation of systemic disease,<br />

including systemic neoplasia, when abdominal<br />

palpation may not fully define abdominal disease. Cats<br />

with heart murmurs should undergo echocardiography<br />

before anesthesia, if possible. This not only allows a<br />

proper anesthetic induction, protocol to be chosen but<br />

also potentially identifies any underlying or <strong>com</strong>plicating<br />

disease pro<strong>ce</strong>sses. The acquired information can<br />

also guide treatment choi<strong>ce</strong>s (e.g., Is the animal a good<br />

candidate for chemotherapy?).<br />

TREATMENT<br />

Treatment options include surgical removal,<br />

chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a <strong>com</strong>bination of<br />

these modalities, depending on tumor type and stage. 2<br />

Surgical removal is the only reported treatment attempted<br />

in dogs, either by resection of the trachea 1,2,8,10,11,15,16 or<br />

endoscopic removal by snaring. 6 Surgery is the treatment<br />

of choi<strong>ce</strong> for solitary tracheal tumors without eviden<strong>ce</strong> of<br />

metastatic disease. 30 Surgical therapy may provide shortterm<br />

palliative relief of airway obstruction for tracheal<br />

tumors exhibiting local and metastatic spread. Although<br />

out<strong>com</strong>e was not reported for one dog with a mast <strong>ce</strong>ll<br />

tumor, 11 follow-up times were reported for most dogs<br />

with osteochondroma (6, 7, and 8 months), 6,15,16 leiomyoma<br />

(6 and 7 months), 9,10 ecchondroma/osteochondromal<br />

dysplasia (5 and 12 months), 13 extramedullary plasmacytoma<br />

(3 months), 2 and chondrosar<strong>com</strong>a (9 and 12<br />

months). 8 Therefore, short-term survival with surgical<br />

www.<strong>VetLearn</strong>.<strong>com</strong><br />

Figure 3—Histopathology from a cat with an intratracheal<br />

mass diagnosed as lymphoma. (From Brown MR, Rogers KS,<br />

Mansell KJ, et al: Primary intratracheal lymphosar<strong>com</strong>a in<br />

four cats. JAAHA 39:468–472, 2003; with permission)<br />

resection appears adequate, but long-term prognosis cannot<br />

be fully evaluated.<br />

Cats with intratracheal adenocarcinoma have been<br />

followed for up to 17 months. Two cats that had surgical<br />

resection were clinically well at 3 and 12 months. 20,22<br />

One cat had an adenocarcinoma suctioned during<br />

bronchoscopy twi<strong>ce</strong>, affording the cat an additional 17<br />

months of life. 18 Intratracheal lymphoma has not<br />

responded well to surgical removal alone. One cat had<br />

recurren<strong>ce</strong> of disease within 10 days, 22 and another had<br />

systemic lymphoma at 4 months postoperatively. 17<br />

The main indication for radiation and chemotherapy<br />

is for intratracheal tumors of lymphoid origin. This<br />

extranodal lymphoma is quite sensitive to radiation<br />

therapy and should be considered immediately after the<br />

cytologic or histologic diagnosis has been made. Radiation<br />

provides a rapid reduction of tumor burden, allowing<br />

a more immediate improvement in the patient’s respiratory<br />

status. Chemotherapy can also delay local or<br />

systemic recurren<strong>ce</strong> of lymphoma. Two cats were tumor<br />

free for 17 and 21 months after a <strong>com</strong>bination of<br />

chemotherapy and radiation was used to treat intratracheal<br />

lymphoma. 25<br />

PROGNOSIS<br />

Prognosis depends on tumor type, stage of disease,<br />

and underlying disease. Osteochondromas of young<br />

dogs appear to carry the best prognosis. Other canine<br />

and feline tracheal tumors have not been followed longterm<br />

after surgical resection, but patients appear to<br />

respond well to surgery, reportedly with survival times<br />

of several months. Cats with tracheal lymphoma may<br />

do well after radiation, systemic chemotherapy, or a<br />

<strong>com</strong>bination of these two modalities.

Compendium November 2003 Primary Tracheal Tumors in Dogs and Cats 859<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Primary intratracheal neoplasia is un<strong>com</strong>mon in dogs<br />

and cats, with only 37 cases reported in the veterinary<br />

literature. Clinical signs are associated with airway<br />

obstruction, including dyspnea, wheezing, and exercise<br />

intoleran<strong>ce</strong>. Radiography often reveals a soft tissue density<br />

within the tracheal lumen. Bronchoscopy allows<br />

direct visualization and sampling for cytology and<br />

histopathology. Treatment re<strong>com</strong>mendations may<br />

include surgical removal, chemotherapy, radiation therapy,<br />

or a <strong>com</strong>bination of these methods, depending on<br />

the tumor type and stage. Until long-term follow-up is<br />

observed and reported, the prognosis for these patients<br />

must be considered guarded. Prognosis most likely<br />

depends on tumor type.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Carlisle CH, Biery DN, Thrall DE: Tracheal and laryngeal<br />

tumors in the dog and cat: Literature review and 13 additional<br />

patients. Vet Radiol 32(5):229–235, 1991.<br />

2. Chaffin K, Cross AR, Allen SW, et al: Extramedullary plasmacytoma<br />

in the trachea of a dog. JAVMA 212(10):1579–1581,<br />

1998.<br />

3. Ogilvie GK, Moore AS: Tumors of the respiratory tract, in<br />

Feline Oncology. Yardley, PA, Veterinary Learning Systems, 2001,<br />

pp 368–384.<br />

4. Stann SE, Bauer TG: Respiratory tract tumors. Vet Clin North<br />

Am Small Anim Pract 15:535–556, 1985.<br />

5. Withrow SJ: Tumors of the respiratory system, in Clinical Veterinary<br />

Oncology. Philadelphia, Lippincott, 1989, pp 215–233.<br />

6. Withrow SJ, Holmberg DL, Rosychuk RA, et al: Treatment of a<br />

tracheal osteochondroma with an overlapping end-to-end tracheal<br />

anastomosis. JAAHA 14(4):469–473, 1978.<br />

7. Hill JE, Mahaffey EA, Farrell RL: Tracheal carcinoma in a dog.<br />

J Comp Pathol 97:705–707, 1987.<br />

8. Aron DN, DeVries R, Short CE: Primary tracheal chondrosar<strong>com</strong>a<br />

in a dog: A case report with description of surgical and<br />

anesthetic techniques. JAAHA 16:31–37, 1980.<br />

9. Black AP, Liu S, Randolph JF: Primary tracheal leiomyoma in a<br />

dog. JAVMA 179:179, 905–907, 1981.<br />

10. Bryan RD, Frame RW, Kier AB: Tracheal leiomyoma in a dog.<br />

JAVMA 178:1069–1070, 1981.<br />

11. Harvey HJ, Sykes G: Tracheal mast <strong>ce</strong>ll tumor in a dog. JAVMA<br />

180:1097–1100, 1982.<br />

12. Brodey RS, O’Brien J, Berg P, et al: Osteosar<strong>com</strong>a of the upper<br />

airway in the dog. JAVMA 155:1460–1464, 1969.<br />

13. Carb A, Halliwell WH: Osteochondral dysplasias of the canine<br />

trachea. JAAHA 17:193–199, 1981.<br />

14. Dubielzig RR, Dickey DL: Tracheal osetochondroma in a young<br />

dog. Vet Med Small Anim Clin 73:1288–1290, 1978.<br />

15. Hough JD, Krahwinkel DJ, Evans AT, et al: Tracheal osteochondroma<br />

in a dog. JAVMA 170(12):1416–1418, 1977.<br />

16. Gourley IG, Morgan JP, Gould DH: Tracheal osteochondroma<br />

in a dog: A case report. J Small Anim Pract 11:327–335, 1970.<br />

www.<strong>VetLearn</strong>.<strong>com</strong><br />

17. Beaumont PR: Intratracheal neoplasia in two cats. J Small Anim<br />

Pract 23:29–35, 1982.<br />

18. Neer TM, Zeman D: Tracheal adenocarcinoma in a cat and<br />

review of the literature. JAAHA 23(4):377–380, 1987.<br />

19. Cain GR, Manley P: Tracheal adenocarcinoma in a cat. JAVMA<br />

182(6):614–616, 1983.<br />

20. Evers P, Sukhiani HR, Sumner-Smith G, et al: Tracheal adenocarcinoma<br />

in two domestic shorthaired cats. J Small Anim Pract<br />

35:217–220, 1994.<br />

21. Glock R: Primary pulmonary adenomas of the feline. Iowa State<br />

University Veterinarian 23:155–156, 1961.<br />

22. Zimmerman U, Muller F, Pfleghaar S: Zwei falle von histogenetisch<br />

unterschiedlichen trachealtmoren bei katzen. Kleintierpraxis<br />

37:409–442, 1992.<br />

23. Schnieder PR, Smith CW, Feller DL: Histiocytic lymphosar<strong>com</strong>a<br />

of the trachea in a cat. JAAHA 15:485–487, 1979.<br />

24. Kim DY, Kim JR, Taylor W, et al: Primary extranodal lymphosar<strong>com</strong>a<br />

of the trachea in a cat. J Vet Med Sci 58(7):703–<br />

706, 1996.<br />

25. Brown MR, Rogers KS: Primary intratracheal lymphoma in four<br />

cats. JAAHA, in press.<br />

26. Lobetti RG, Williams MC: Anaplastic tracheal squamous <strong>ce</strong>ll<br />

carcinoma in a cat. J South Afr Vet Assoc 63:132–133, 1992.<br />

27. Veith LA: Squamous <strong>ce</strong>ll carcinoma of the trachea in a cat.<br />

Feline Pract 4(1):30–32, 1974.<br />

28. Norris AM, Henderson RA, Withrow SJ: Respiratory system, in<br />

Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders,<br />

1985, pp 2583–2592.<br />

29. Ettinger SJ, Ti<strong>ce</strong>r JW: Diseases of the trachea, in Textbook of Veterinary<br />

Internal Medicine, ed 3. Philadelphia, WB Saunders,<br />

1989, pp 795–815.<br />

30. Bell FW: Neoplastic diseases of the thorax. Vet Clin North Am<br />

Small Anim Pract 17:387–409, 1987.<br />

31. Sheaffer KA, Dillon AR: Obstructive tracheal mass due to an<br />

inflammatory polyp in a cat. JAAHA 32:431–434, 1996.<br />

32. Brovida C, Castagnaro M: Tracheal obstruction due to an<br />

eosinophilic granuloma in a dog: Surgical treatment and clinicopathological<br />

observations. JAAHA 28:8–12, 1992.<br />

33. Dill GS, Stookey JL, Whitney GD: Nodular amyloidosis in the<br />

trachea of a dog. Vet Pathol 9:238–242, 1972.<br />

34. Burrows CF, O’Briend JA, Biery DN: Pneumothorax due to<br />

Filaroides osleri infestation in the dog. J Small Anim Pract 3:613–<br />

618, 1972.<br />

35. Pearson GR, Lane JG, Holt PE, et al: Chondromatous hamartomas<br />

of the respiratory tract in the dog. J Small Anim Pract 28:<br />

705–712, 1987.<br />

36. Kelly DF: Papillomatosis of the trachea and bronchi in a dog. J<br />

Pathol 88:590–591, 1964.<br />

37. DeRick A, VanBree H, Hoorens J, et al: Tracheal obstruction<br />

due to a nodular hyperplastic tracheitis in a dog. J Small Anim<br />

Pract 18:473–477, 1977.<br />

38. Knecht CD, Schall WD, Barrett R: Iatrogenic tracheostenosis in<br />

a dog. JAVMA 160(10):1427–1429, 1972.<br />

39. Gordon W: Surgical correction of tracheal stenosis in a dog.<br />

JAVMA 162(6):479–480, 1973.

860 Small Animal/Exotics Compendium November 2003<br />

ARTICLE<br />

CE<br />

<strong>#4</strong> CE TEST<br />

The article you have read qualifies for 1.5 contact<br />

hours of Continuing Education Credit from<br />

the Auburn University College of Veterinary Med-<br />

icine. Choose the best answer to each of the follow-<br />

ing questions; then mark your answers on the<br />

postage-paid envelope inserted in Compendium.<br />

1. Because canine tracheal neoplasms present in a bimodal<br />

age distribution, dogs 2 years of age or younger are<br />

most likely to present with<br />

a. mast <strong>ce</strong>ll tumor. c. chondrosar<strong>com</strong>a.<br />

b. leiomyoma. d. osteochondroma.<br />

2. Which of the following are reported clinical signs for<br />

patients with tracheal tumors?<br />

a. wheezing and dyspnea<br />

b. cough and exercise intoleran<strong>ce</strong><br />

c. voi<strong>ce</strong> change or inability to bark<br />

d. all of the above<br />

3. Which of the following is the diagnostic pro<strong>ce</strong>dure of<br />

choi<strong>ce</strong> for confirming suspicions of an intratracheal<br />

mass?<br />

a. contrast radiography c. bronchoscopy<br />

b. survey radiography d. exploratory surgery<br />

4. Which of the following parasites may cause intratracheal<br />

nodules as a result of tissue reaction against the<br />

parasite?<br />

a. Oslerus hirthi<br />

b. Aelurostrongylus abstrusus<br />

c. Filaroides osleri<br />

d. Paragonimus kellicotti<br />

5. An unstable, dyspneic cat has been anesthetized, and<br />

bronchoscopy has revealed a mass. Cytology of the<br />

mass reveals lymphoma. Before the cat recovers from<br />

anesthesia, the therapy that would offer the quickest<br />

reduction of the tumor burden would be<br />

a. chemotherapy.<br />

b. radiation therapy.<br />

www.<strong>VetLearn</strong>.<strong>com</strong><br />

c. surgical excision.<br />

d. medical management with prednisone.<br />

6. Surgical resection is the treatment of choi<strong>ce</strong> for all of<br />

the following ex<strong>ce</strong>pt<br />

a. lymphoma.<br />

b. adenocarcinoma.<br />

c. osteochondroma.<br />

d. leiomyoma.<br />

7. Which of the following is considered a benign osteocartilaginous<br />

tumor that grows in synchrony with the<br />

rest of the musculoskeletal system and should stop<br />

growing at skeletal maturity?<br />

a. leiomyoma<br />

b. chondroma<br />

c. osteochondroma<br />

d. osteosar<strong>com</strong>a<br />

8. When a patient presents with clinical signs consistent<br />

with a tracheal tumor, the first priority should be to<br />

a. obtain plain radiographs to identify the problem.<br />

b. stabilize the patient with oxygen and other supportive<br />

measures.<br />

c. perform bronchoscopy to obtain a sample for cytology<br />

and histopathology.<br />

d. submit blood for a <strong>com</strong>plete blood <strong>ce</strong>ll count and<br />

chemistry profile.<br />

9. All of the following have been noted in cats with intratracheal<br />

tumors ex<strong>ce</strong>pt<br />

a. overexpansion of the lungs.<br />

b. flattening of the diaphragm.<br />

c. underexpansion of the lungs.<br />

d. prominent pulmonary vasculature.<br />

10. Which of the following statements regarding FIV and<br />

FeLV is true?<br />

a. FIV is <strong>com</strong>mon in cats with tracheal neoplasia.<br />

b. FIV and FeLV are <strong>com</strong>mon in cats with tracheal<br />

neoplasia.<br />

c. FIV <strong>test</strong>ing was reported in four of 19 cats, and all<br />

cats were negative for the virus.<br />

d. All cats with tracheal neoplasia are FeLV positive.