updating brignoni-ponce - New York University School of Law

updating brignoni-ponce - New York University School of Law

updating brignoni-ponce - New York University School of Law

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

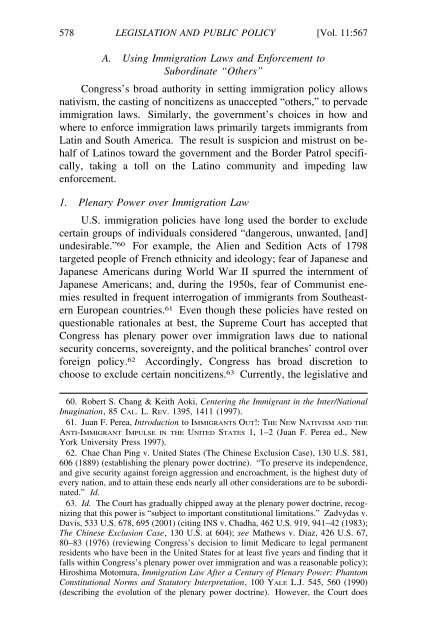

578 LEGISLATION AND PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 11:567<br />

A. Using Immigration <strong>Law</strong>s and Enforcement to<br />

Subordinate “Others”<br />

Congress’s broad authority in setting immigration policy allows<br />

nativism, the casting <strong>of</strong> noncitizens as unaccepted “others,” to pervade<br />

immigration laws. Similarly, the government’s choices in how and<br />

where to enforce immigration laws primarily targets immigrants from<br />

Latin and South America. The result is suspicion and mistrust on behalf<br />

<strong>of</strong> Latinos toward the government and the Border Patrol specifically,<br />

taking a toll on the Latino community and impeding law<br />

enforcement.<br />

1. Plenary Power over Immigration <strong>Law</strong><br />

U.S. immigration policies have long used the border to exclude<br />

certain groups <strong>of</strong> individuals considered “dangerous, unwanted, [and]<br />

undesirable.” 60 For example, the Alien and Sedition Acts <strong>of</strong> 1798<br />

targeted people <strong>of</strong> French ethnicity and ideology; fear <strong>of</strong> Japanese and<br />

Japanese Americans during World War II spurred the internment <strong>of</strong><br />

Japanese Americans; and, during the 1950s, fear <strong>of</strong> Communist enemies<br />

resulted in frequent interrogation <strong>of</strong> immigrants from Southeastern<br />

European countries. 61 Even though these policies have rested on<br />

questionable rationales at best, the Supreme Court has accepted that<br />

Congress has plenary power over immigration laws due to national<br />

security concerns, sovereignty, and the political branches’ control over<br />

foreign policy. 62 Accordingly, Congress has broad discretion to<br />

choose to exclude certain noncitizens. 63 Currently, the legislative and<br />

60. Robert S. Chang & Keith Aoki, Centering the Immigrant in the Inter/National<br />

Imagination, 85 CAL. L. REV. 1395, 1411 (1997).<br />

61. Juan F. Perea, Introduction to IMMIGRANTS OUT!: THE NEW NATIVISM AND THE<br />

ANTI-IMMIGRANT IMPULSE IN THE UNITED STATES 1, 1–2 (Juan F. Perea ed., <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>York</strong> <strong>University</strong> Press 1997).<br />

62. Chae Chan Ping v. United States (The Chinese Exclusion Case), 130 U.S. 581,<br />

606 (1889) (establishing the plenary power doctrine). “To preserve its independence,<br />

and give security against foreign aggression and encroachment, is the highest duty <strong>of</strong><br />

every nation, and to attain these ends nearly all other considerations are to be subordinated.”<br />

Id.<br />

63. Id. The Court has gradually chipped away at the plenary power doctrine, recognizing<br />

that this power is “subject to important constitutional limitations.” Zadvydas v.<br />

Davis, 533 U.S. 678, 695 (2001) (citing INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919, 941–42 (1983);<br />

The Chinese Exclusion Case, 130 U.S. at 604); see Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67,<br />

80–83 (1976) (reviewing Congress’s decision to limit Medicare to legal permanent<br />

residents who have been in the United States for at least five years and finding that it<br />

falls within Congress’s plenary power over immigration and was a reasonable policy);<br />

Hiroshima Motomura, Immigration <strong>Law</strong> After a Century <strong>of</strong> Plenary Power: Phantom<br />

Constitutional Norms and Statutory Interpretation, 100 YALE L.J. 545, 560 (1990)<br />

(describing the evolution <strong>of</strong> the plenary power doctrine). However, the Court does