Java-Sept-Pages-2018

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

also adopted the practice, as have some airports and<br />

other locations where errant birds can pose serious<br />

hazards. There’s even a program in France to train<br />

eagles to attack terrorist drones.<br />

Threats from Arizona’s skies come mainly in the<br />

form of beaks and bowel movements. “A grackle<br />

had grabbed a lady’s piece of bacon and, I don’t<br />

know why, she decided she wanted it back,” White<br />

explained. “She tried to grab it from the grackle, and<br />

it pecked her finger. I think that was the incident that<br />

got us hired.”<br />

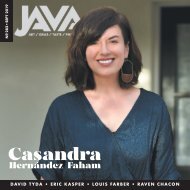

Sonoran works with the Fairmont Scottsdale Princess<br />

resort, where they also offer weekly Hawk Talks.<br />

With White currently in Yuma working on an exciting<br />

new project, Knight currently runs the talks, along<br />

with Jeffrey Trainer, Sonoran’s director of operations.<br />

They answer questions, pose for pictures with their<br />

birds and discuss falconry with the general public.<br />

“People don’t get close to birds of prey, especially<br />

owls, because they’re out after dark,” Knight said. “A<br />

lot of people put rodenticides out to get rid of desert<br />

mice and rats and all that. It’s very harmful to the<br />

ecosystem. People don’t think of how that can affect<br />

birds and other animals, so it’s nice to educate them.”<br />

Through their non-profit arm, Sonoran offers<br />

educational programming for schools in low-income<br />

neighborhoods. They usually bring a hawk, a falcon<br />

and an owl and discuss the differences among them.<br />

They educate students about conservation and<br />

potential career paths working with animals or in<br />

farming. For many students, these visits are their first<br />

interactions with such animals.<br />

“Most kids know more about drones right now than<br />

they know about any type of bird of prey,” Trainer<br />

said. White in particular enjoys these settings<br />

because she provides a unique role model, being a<br />

business-owning woman of color – and one who also<br />

happens to have a badass bird perched on her fist.<br />

While White and the other handlers at Sonoran<br />

all have strong feelings about their birds and the<br />

environment, the great-tailed grackles at the Princess<br />

resort in particular seem to have strong feelings in<br />

return, if not exactly reciprocal ones. “They’re a trip,<br />

and they’re smart, too,” Tiffany said of her bird bêtes<br />

noires. “All I have to do is walk through there, and<br />

birds are screaming at me. I’m not kidding – they’ll<br />

actually take things and drop them on my head.”<br />

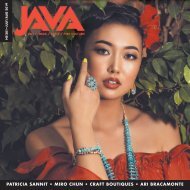

Sonoran’s largest contract to date, and the reason<br />

for White’s recent move to Yuma, came after a<br />

phone call from Paula Rivadeneira, a food safety<br />

32 JAVA<br />

MAGAZINE<br />

and wildlife extension specialist at the University of<br />

Arizona’s Cooperative Extension in Yuma.<br />

Agriculture added $7.3 billion to Arizona’s economy in<br />

2014. Farming is particularly vital to Yuma, the winter<br />

green capital of the US, which produces 90 percent<br />

of our country’s leafy vegetables between November<br />

and March.<br />

Earlier this year, an E. coli outbreak in romaine lettuce<br />

grown there led to five deaths and left hundreds<br />

sick across 35 states. A bacterium primarily living in<br />

animals’ digestive tracts, E. coli is thought to spread<br />

to crops when pests defecate on or near fields. Flood<br />

irrigation then spreads the bacteria.<br />

Farmers use a number of methods to deter birds from<br />

their fields, everything from scarecrows to Mylar<br />

streamers to acoustic cannons, lasers and poisons.<br />

Rivadeneira, who has a PhD in biology, thought there<br />

must be a better way.<br />

“I’m a wildlife biologist, and my goal is really to help<br />

the farmers figure out a more natural and economical<br />

way to keep wildlife out of their fields,” Rivadeneira<br />

said. “In most cases, they’re using lots of different<br />

deterrents, including having people standing in the<br />

fields to keep animals out. That just didn’t make<br />

sense to me.”<br />

While in the past Americans have tended to view<br />

nature and business as diametrically opposed,<br />

Rivadeneira is one of a growing number who believe<br />

natural and human systems can be made to function<br />

in better harmony. She began researching alternative<br />

approaches to pest management when she first<br />

learned about falconry-based pest abatement.<br />

“If the vineyards can do it, why can’t we?”<br />

Rivadeneira asked herself. She called falconers<br />

around the state about her idea, but found only<br />

White willing to talk and help. Rivadeneira asked<br />

White if she would be willing to serve as the<br />

falconer for a grant proposal she was preparing, and<br />

White said yes.<br />

When the Center for Produce Safety awarded them a<br />

$380,000 grant to run a two-year pilot project, White<br />

immediately began packing her bags and assembling<br />

a team of birds. Rivadeneira fixed up an old RV, with<br />

a gift of new tires from a friendly farmer, and set<br />

up the Super Cool Agricultural Testing and Teaching