BCJ_SPRING 17 Digital Edition

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

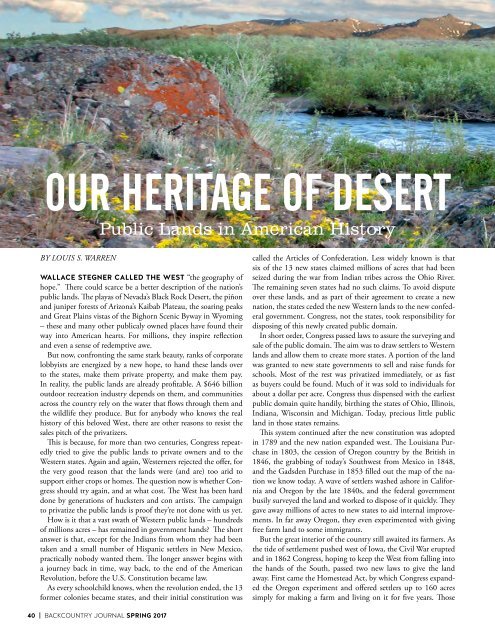

OUR HERITAGE OF DESERT<br />

Public Lands in American History<br />

Bryan Huskey photo<br />

BY LOUIS S. WARREN<br />

WALLACE STEGNER CALLED THE WEST “the geography of<br />

hope.” There could scarce be a better description of the nation’s<br />

public lands. The playas of Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, the piñon<br />

and juniper forests of Arizona’s Kaibab Plateau, the soaring peaks<br />

and Great Plains vistas of the Bighorn Scenic Byway in Wyoming<br />

– these and many other publicaly owned places have found their<br />

way into American hearts. For millions, they inspire reflection<br />

and even a sense of redemptive awe.<br />

But now, confronting the same stark beauty, ranks of corporate<br />

lobbyists are energized by a new hope, to hand these lands over<br />

to the states, make them private property, and make them pay.<br />

In reality, the public lands are already profitable. A $646 billion<br />

outdoor recreation industry depends on them, and communities<br />

across the country rely on the water that flows through them and<br />

the wildlife they produce. But for anybody who knows the real<br />

history of this beloved West, there are other reasons to resist the<br />

sales pitch of the privatizers.<br />

This is because, for more than two centuries, Congress repeatedly<br />

tried to give the public lands to private owners and to the<br />

Western states. Again and again, Westerners rejected the offer, for<br />

the very good reason that the lands were (and are) too arid to<br />

support either crops or homes. The question now is whether Congress<br />

should try again, and at what cost. The West has been hard<br />

done by generations of hucksters and con artists. The campaign<br />

to privatize the public lands is proof they’re not done with us yet.<br />

How is it that a vast swath of Western public lands – hundreds<br />

of millions acres – has remained in government hands? The short<br />

answer is that, except for the Indians from whom they had been<br />

taken and a small number of Hispanic settlers in New Mexico,<br />

practically nobody wanted them. The longer answer begins with<br />

a journey back in time, way back, to the end of the American<br />

Revolution, before the U.S. Constitution became law.<br />

As every schoolchild knows, when the revolution ended, the 13<br />

former colonies became states, and their initial constitution was<br />

called the Articles of Confederation. Less widely known is that<br />

six of the 13 new states claimed millions of acres that had been<br />

seized during the war from Indian tribes across the Ohio River.<br />

The remaining seven states had no such claims. To avoid dispute<br />

over these lands, and as part of their agreement to create a new<br />

nation, the states ceded the new Western lands to the new confederal<br />

government. Congress, not the states, took responsibility for<br />

disposing of this newly created public domain.<br />

In short order, Congress passed laws to assure the surveying and<br />

sale of the public domain. The aim was to draw settlers to Western<br />

lands and allow them to create more states. A portion of the land<br />

was granted to new state governments to sell and raise funds for<br />

schools. Most of the rest was privatized immediately, or as fast<br />

as buyers could be found. Much of it was sold to individuals for<br />

about a dollar per acre. Congress thus dispensed with the earliest<br />

public domain quite handily, birthing the states of Ohio, Illinois,<br />

Indiana, Wisconsin and Michigan. Today, precious little public<br />

land in those states remains.<br />

This system continued after the new constitution was adopted<br />

in <strong>17</strong>89 and the new nation expanded west. The Louisiana Purchase<br />

in 1803, the cession of Oregon country by the British in<br />

1846, the grabbing of today’s Southwest from Mexico in 1848,<br />

and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853 filled out the map of the nation<br />

we know today. A wave of settlers washed ashore in California<br />

and Oregon by the late 1840s, and the federal government<br />

busily surveyed the land and worked to dispose of it quickly. They<br />

gave away millions of acres to new states to aid internal improvements.<br />

In far away Oregon, they even experimented with giving<br />

free farm land to some immigrants.<br />

But the great interior of the country still awaited its farmers. As<br />

the tide of settlement pushed west of Iowa, the Civil War erupted<br />

and in 1862 Congress, hoping to keep the West from falling into<br />

the hands of the South, passed two new laws to give the land<br />

away. First came the Homestead Act, by which Congress expanded<br />

the Oregon experiment and offered settlers up to 160 acres<br />

simply for making a farm and living on it for five years. Those<br />

who did not want to wait to “prove up” could buy the land after<br />

six months, at $1.25 an acre.<br />

Second, Congress passed the Pacific Railway Act, which gave to<br />

the corporations building the new transcontinental railroads ten<br />

square miles of land for every mile of track they laid. Congress<br />

later doubled this generous subsidy and, before the railroad boom<br />

was over, an area bigger than California would pass to the railroad<br />

companies who mostly sold it to settlers and speculators.<br />

With so much cheap or even free land suddenly available,<br />

during the 1870s eager farmers swarmed into Nebraska, Kansas<br />

and the Dakotas. But the rush hit a headwind. Because of the rain<br />

shadow cast by the Rocky Mountains, precipitation diminishes<br />

markedly on the west side of the Hundredth Meridian. Most of<br />

this high Great Plains country– the western two-thirds of Kansas,<br />

Nebraska and the Dakotas, all of Wyoming and most of Colorado<br />

and Montana, was too cold and too dry to allow much farming.<br />

The arid Plains were not the only obstacles. Further west still,<br />

the mountains of the Sierra Nevada and the Cascades cast their<br />

own rain shadows. Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico and much of<br />

Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and even southern California were<br />

unrelentingly dry.<br />

When it came to dispensing with this thirsty public domain,<br />

Congress would act in ways visionary, desperate or craven – and<br />

sometimes all three. In 1872, they recognized a new value for<br />

the remote highlands and established Yellowstone National Park,<br />

beginning a tradition of reserving scenic wonders for public enjoyment.<br />

But that same year, they began to up the ante on the great giveaway.<br />

They offered land for five dollars an acre to anybody who<br />

staked a valid mining claim on it. The next year, in 1873, they<br />

offered any homesteader a second 160-acre parcel in return for<br />

planting trees on it, in hopes that trees would bring rain. (They<br />

did not; the trees mostly died.) They began to enlarge maximum<br />

homestead claims in hopes of compensating for the land’s aridity.<br />

By 1909, they had doubled the old 160 acre homesteading limit<br />

to 320 acres, and in some places to 640 acres.<br />

At the same time, Congress reserved other lands in hopes of<br />

better sustaining Western settlements. Recognizing that farms<br />

and cities on the dry lowlands depended on rivers fed by mountain<br />

snow, and that those rivers could erode and fill with sediment<br />

if their banks were ploughed, overgrazed or overcut, Congress<br />

in 1891 passed a law allowing the creation of “forest reserves”<br />

– soon to be called national forests. These high elevation stands<br />

of trees under federal management would protect Western rivers<br />

and streams.<br />

Putting those rivers to use, Congress set out to water the desert<br />

they had been unable to give away, with dams and irrigation<br />

works funded by the National Reclamation Act of 1902. Soon<br />

they were offering “reclamation homesteads” on these projects,<br />

and under this and other, expanded versions of the old homestead<br />

law, more land was claimed in homesteads after 1900 than before.<br />

But the growth of private land ownership finally stalled. The<br />

1920s saw a ferocious Western drought coincide with a global<br />

glut of grain. Farms and ranches that barely got enough rain in<br />

good years now turned to dust, while market prices for their produce<br />

plummeted. Many settlers simply abandoned their homestead<br />

claims without proving up, and the land reverted to federal<br />

ownership. In the end, homesteaders would take 269 million<br />

acres from the public lands. But by 1930, they had rejected an<br />

area almost as large, 200 million acres, as too high or dry. These<br />

lands remained unclaimed by private owners or any government<br />

agency.<br />

Eager to cut federal expenses, President Herbert Hoover tried<br />

to give to the states some of the remaining public lands. But the<br />

states refused them. As George H. Dern, governor of Utah from<br />

1925 to 1933, explained, the states already owned millions of<br />

acres “of this same kind of land, which they can neither sell nor<br />

lease, and which is yielding no income. Why should they want<br />

more of this precious heritage of desert?”<br />

As that dismal decade wore on and Plains states choked on<br />

the fatal storms of the Dust Bowl, it became clear that farming<br />

the arid lands had been a disaster. Western state governors, beset<br />

40 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL <strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong><br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 41