BCJ_SPRING 17 Digital Edition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

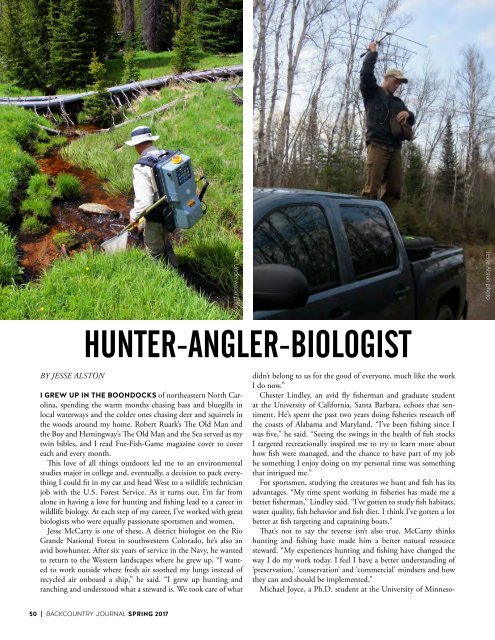

Alec Underwood photo<br />

Jesse Alston photo<br />

ta-Duluth studying habitat use by martens and fishers (members<br />

of the weasel family), says hunting has helped him do better research<br />

as well. “The quiet solitude of a deer stand is often a good<br />

place for me to think deeply and critically about questions I’m<br />

grappling with in my research,” he said. I can’t say that I disagree.<br />

Hunting also helps with work in the field. “Hunting, in particular,<br />

has helped me learn about navigation, dealing with harsh<br />

weather and troubleshooting when something doesn’t go according<br />

to plan,” he said. “It has certainly provided ample opportunity<br />

for me to hone skills and to think about the factors that influence<br />

animal behavior.”<br />

Having hunters and anglers in game and fish agency positions<br />

benefits other sportsmen, too. As Lindley said, “I think it’s vital<br />

to have fishermen and hunters in wildlife management positions.<br />

People who have a vested interest in the health of fish and wildlife<br />

stocks are particularly well suited for positions of management.”<br />

This leads into perhaps the biggest issue facing hunters and anglers<br />

today: Conservation. Wildlife biologists rarely get to work<br />

with species that are doing well. Despite our best efforts, our careers<br />

are peppered with the death and destruction of the wildlife<br />

we love. This can lead to tension with other groups who love wildlife<br />

and think we could study and manage them better.<br />

Fellow sportsmen are one of those groups and can both exacerbate<br />

and alleviate this problem. “I know the sentiment among<br />

many fishermen is that regulations are overbearing,” Lindley said.<br />

“But I think the only reason stocks are starting to show an uptick<br />

in the last few years is because managers and fishermen alike are<br />

coming together to protect fish in new and inventive ways.”<br />

In managing the demands of the public, biologists also often<br />

face intense political pressure, from both above and below. As I’ve<br />

heard one biologist I know say, expecting biologists not to advocate<br />

for wildlife is like expecting dentists not to advocate for clean<br />

teeth. But agency biologists often can’t advocate their positions<br />

out of fear that the public might not agree.<br />

Despite these difficulties, I’m convinced there’s no better job.<br />

I’ve spent over half my workdays over the past few years in the<br />

great outdoors, becoming a better scientist and a better sportsman<br />

along the way. I’ve met a lot of great biologists and hope other<br />

sportsmen can do the same. It’s easy to grumble about regulations,<br />

but ultimately, no one has a greater stake in successful management<br />

than sportsmen-biologists, and no one takes more pride in<br />

a job well done.<br />

McCarty captures this idea perfectly: “Managing wildlife resources<br />

for the American people gives me a sense of pride and<br />

patriotism similar to my time in the service.”<br />

Among wildlife biologists, he’s far from alone. So next time<br />

you meet one of us, let us know what you’re seeing in the field.<br />

We’re glad to hear your stories, and we might have some for you<br />

as well.<br />

Jesse is a graduate student in the University of Wyoming’s zoology<br />

and physiology department and a proud BHA member. You can check<br />

out his research and field photography at jmalston.com or have a conversation<br />

on Twitter @integratecology.<br />

HUNTER-ANGLER-BIOLOGIST<br />

BY JESSE ALSTON<br />

I GREW UP IN THE BOONDOCKS of northeastern North Carolina,<br />

spending the warm months chasing bass and bluegills in<br />

local waterways and the colder ones chasing deer and squirrels in<br />

the woods around my home. Robert Ruark’s The Old Man and<br />

the Boy and Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea served as my<br />

twin bibles, and I read Fur-Fish-Game magazine cover to cover<br />

each and every month.<br />

This love of all things outdoors led me to an environmental<br />

studies major in college and, eventually, a decision to pack everything<br />

I could fit in my car and head West to a wildlife technician<br />

job with the U.S. Forest Service. As it turns out, I’m far from<br />

alone in having a love for hunting and fishing lead to a career in<br />

wildlife biology. At each step of my career, I’ve worked with great<br />

biologists who were equally passionate sportsmen and women.<br />

Jesse McCarty is one of these. A district biologist on the Rio<br />

Grande National Forest in southwestern Colorado, he’s also an<br />

avid bowhunter. After six years of service in the Navy, he wanted<br />

to return to the Western landscapes where he grew up. “I wanted<br />

to work outside where fresh air soothed my lungs instead of<br />

recycled air onboard a ship,” he said. “I grew up hunting and<br />

ranching and understood what a steward is. We took care of what<br />

didn’t belong to us for the good of everyone, much like the work<br />

I do now.”<br />

Chester Lindley, an avid fly fisherman and graduate student<br />

at the University of California, Santa Barbara, echoes that sentiment.<br />

He’s spent the past two years doing fisheries research off<br />

the coasts of Alabama and Maryland. “I’ve been fishing since I<br />

was five,” he said. “Seeing the swings in the health of fish stocks<br />

I targeted recreationally inspired me to try to learn more about<br />

how fish were managed, and the chance to have part of my job<br />

be something I enjoy doing on my personal time was something<br />

that intrigued me.”<br />

For sportsmen, studying the creatures we hunt and fish has its<br />

advantages. “My time spent working in fisheries has made me a<br />

better fisherman,” Lindley said. “I’ve gotten to study fish habitats,<br />

water quality, fish behavior and fish diet. I think I’ve gotten a lot<br />

better at fish targeting and captaining boats.”<br />

That’s not to say the reverse isn’t also true. McCarty thinks<br />

hunting and fishing have made him a better natural resource<br />

steward. “My experiences hunting and fishing have changed the<br />

way I do my work today. I feel I have a better understanding of<br />

‘preservation,’ ‘conservation’ and ‘commercial’ mindsets and how<br />

they can and should be implemented.”<br />

Michael Joyce, a Ph.D. student at the University of Minneso-<br />

50 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL <strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong><br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 51