BCJ_FALL17 Digital Edition

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

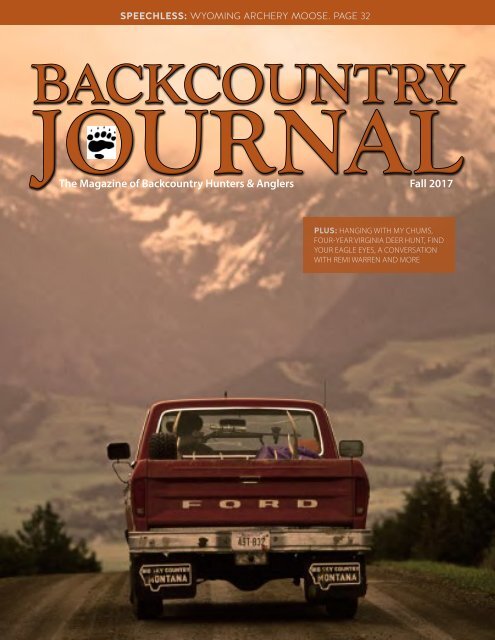

SPEECHLESS: WYOMING ARCHERY MOOSE. PAGE 32<br />

BACKCOUNTRY<br />

JOURNAL<br />

The Magazine of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Fall 2017<br />

PLUS: HANGING WITH MY CHUMS,<br />

FOUR-YEAR VIRGINIA DEER HUNT, FIND<br />

YOUR EAGLE EYES, A CONVERSATION<br />

WITH REMI WARREN AND MORE<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 1

2 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE<br />

TRUE GRIT<br />

“TEN MORE MINUTES, CID.” She had stopped talking a few minutes<br />

before, a telltale sign of something awry. It’s a trait we share. We were on a<br />

trip of a lifetime put together by First Lite to celebrate her 9th birthday: her<br />

first backpacking trip into the storied Frank Church-River of No Return<br />

Wilderness in central Idaho.<br />

It was hot – too hot. The first mile of the hike had been easy going<br />

along Marsh Creek. The excitement was heavy and the promise of hungry<br />

cutthroat trout motivating. But the next mile got steeper. Cid’s llama, Marshall,<br />

ate some yarrow, which made its mouth numb, which in turn made<br />

him slobber incessantly. In good time, said slobber dripped on the back of<br />

Cid’s calves.<br />

As happens with a group, our plans to stop for lunch in “another 15<br />

minutes” turned into 20, then 30 minutes. Finally, we found a respite next<br />

to the creek and I got Cid to dunk her head in the cool, clean water. Tears<br />

commenced, along with pleas to head home. My young daughter had hit<br />

her limit.<br />

If you’ve spent any time in the woods or on the water you know the<br />

feeling: a conviction that it can’t get any worse and won’t get any better. It<br />

doesn’t matter if you hunt, fish, kayak, mountain climb or mountain bike ,<br />

you know that feeling and how hard it is to overcome.<br />

Grit. That word best describes the moment when it’s all up to you, no<br />

one else, to carry onward. The mountains, streams and cliffs don’t care who<br />

you are. They give handouts to no one. There are no shortcuts, no one to do<br />

it for you. When the chips are down, you have to dig deep inside and find<br />

that spirit to carry you through. Grit is one of the endearing qualities that<br />

only public lands and waters can create.<br />

Cid’s face gradually changed from bright red to a softer shade of pink.<br />

Her breath had returned to normal and she had added some much-needed<br />

fuel to her tank. She still wasn’t convinced she could power through, but her<br />

mood was changing. She started to talk again.<br />

I decided to tell her a story about Theodore Roosevelt, an often-discussed<br />

icon in the Tawney household. Roosevelt grew up with debilitating asthma.<br />

Instead of succumbing to the affliction, he worked hard to overcome it.<br />

He climbed peaks, boxed and lived the strenuous life. He and no one else<br />

made the choice to overcome something that could have easily hampered<br />

his lifestyle. He showed grit.<br />

After finishing the story, I let the words linger and left Cid by herself to<br />

contemplate. When I came back minutes later, she was ready to roll.<br />

Cid crushed it on the remaining mile of trail – a mile even steeper than<br />

the last. She beat many of the adults and raised her arms in triumphant joy<br />

upon reaching our alpine lake destination. Her exuberance had returned,<br />

and she promptly jumped into the icy waters and, for effect, ate a black<br />

stonefly nymph. While my story about T.R. may have motivated her, she<br />

did it herself. She learned a life lesson, and I couldn’t be more proud.<br />

Each and every day, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers members, dedicated<br />

volunteers and badass staff work to protect and promote your public<br />

lands and waters, those place where you too can challenge yourself and find<br />

that inner grit.<br />

We covet those places. We need those places. They’re part of our DNA.<br />

Not only do we channel that grit in the field, it also drives us to protect and<br />

promote those very places.<br />

Enjoy all that fall has to offer, and I hope to see you on the trail. Stay<br />

gritty!<br />

Cidney Tawney and her pack llama, Marshall, take a much-needed<br />

breather on their way to go fish some high alpine lakes deep in the<br />

Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness.<br />

Onward and Upward,<br />

Land Tawney<br />

President & CEO<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 3

WHAT IS BHA?<br />

BACKCOUNTRY HUNTERS & ANGLERS<br />

is a North American conservation<br />

nonprofit 501(c)(3) dedicated to the<br />

conservation of backcountry fish and<br />

wildlife habitat, sustaining and expanding<br />

access to important lands and waters, and<br />

upholding the principles of fair chase.<br />

This is our quarterly magazine. We fight to<br />

maintain and enhance the backcountry<br />

values that define our passions: challenge,<br />

solitude and beauty. Join us. Become<br />

part of the sportsmen’s voice for our wild<br />

public lands, waters and wildlife.<br />

Sign up at www.backcountryhunters.org.<br />

THE SPORTSMEN’S VOICE FOR OUR WILD PUBLIC LANDS, WATERS AND WILDLIFE<br />

Ryan Busse (Montana) Chairman<br />

J.R. Young (California) Treasurer<br />

Sean Carriere (Idaho)<br />

Ted Koch (New Mexico)<br />

Ben O’Brien (Texas)<br />

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus<br />

President & CEO<br />

Land Tawney, tawney@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Alberta Public Lands Coordinator<br />

Aliah Adams Knopff, aliah.knopff@gmail.com<br />

BOARD OF DIRECTORS<br />

STAFF<br />

Ben Bulis (Montana) Vice Chairman<br />

Heather Kelly (Alaska)<br />

T. Edward Nickens (North Carolina)<br />

Mike Schoby (Montana)<br />

Rachel Vandevoort (Montana)<br />

Southeast Chapter Coordinator<br />

Josh Kaywood, josh@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Backcountry Journal Editor<br />

Sam Lungren, sam@backcountryhunters.org<br />

STATE CHAPTERS<br />

BHA HAS MEMBERS across the<br />

continent, with chapters representing<br />

35 states, the District of Columbia and<br />

two provinces. Grassroots public lands<br />

sportsmen and women are the driving<br />

force behind BHA. Learn more about what<br />

BHA is doing in your state on page 26. If<br />

you are looking for ways to get involved,<br />

email your state chapter chair at the<br />

following addresses:<br />

• alaska@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• alberta@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• arizona@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• britishcolumbia@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• california@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• capital@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• colorado@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• idaho@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• michigan@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• minnesota@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• montana@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• nevada@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• newengland@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• newmexico@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• newyork@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• oregon@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• pennsylvania@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• southeast@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• southdakota@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• texas@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• utah@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• washington@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• wisconsin@backcountryhunters.org<br />

4 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017<br />

• wyoming@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Donor and Corporate Relations Manager<br />

Grant Alban, grant@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Southwest Chapter Coordinator<br />

Jason Amaro, jason@backcountryhunters.org<br />

State Policy Director<br />

Tim Brass, tim@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Campus Outreach Coordinator<br />

Sawyer Connelly, sawyer@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Collegiate Curriculum and Outreach Assistant<br />

Trey Curtiss, trey@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Office Manager<br />

Caitlin Frisbie, frisbie@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Conservation Director<br />

John Gale, gale@backcountryhunters.org<br />

New York and Pennsylvania Public Lands Coordinator<br />

Chris Hennessy, c.hennessey@comcast.net<br />

Great Lakes Coordinator<br />

Will Jenkins, will@thewilltohunt.com<br />

JOURNAL CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Jack Ballard, Reid Bryant, Jan Dizard, Natalie England,<br />

Ryan Hughes, Mark Hurst, Ken Keffer, Paul Kemper,<br />

Emily Madieros, Spencer Neuharth, Jared Oakleaf, Tim<br />

Romano, Dusan Smetana, Dale Spartas, Maddie Vincent,<br />

George Wallace, Merv Webb, Dakota Wharry<br />

Cover photo: Dusan Smetana<br />

Backcountry Journal is the quarterly membership<br />

publication of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. All<br />

rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in any<br />

manner without the consent of the publisher. Writing<br />

and photography queries, submissions and advertising<br />

questions contact sam@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Published October 2017. Volume XII, Issue IX<br />

JOIN THE CONVERSATION<br />

Operations Director<br />

Frankie McBurney Olson, frankie@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Central Idaho Coordinator<br />

Mike McConnell, whiteh2omac@gmail.com<br />

Communications Director<br />

Katie McKalip, mckalip@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Social Media and Online Advocacy Coordinator<br />

Nicole Qualtieri, nicole@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Northwest Outreach Coordinator<br />

Jesse Salsberry, jesse@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Membership Coordinator<br />

Ryan Silcox, ryan@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Merchandise and Membership Specialist<br />

Ty Smail, smail@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Chapter Coordinator<br />

Ty Stubblefield, ty@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Interns: Ryan Hughes, Carter Birmingham, Alex Kim, Emily<br />

Madieros, Maddie Vincent, Dakota Wharry<br />

BHA LEGACY PARTNERS<br />

The following Legacy Partners have committed<br />

$1000 or more to BHA for the next three years. To<br />

find out how you can become a Legacy Partner,<br />

please contact grant@backcountryhunters.org.<br />

Lou and Lila Bahin, Bendrix Bailey, Mike Beagle, Sean<br />

Carriere, Chris Cholette, Dave Cline, Dan Edwards,<br />

Todd DeBonis, Blake Fischer, Sarah Foreman, Whit<br />

Fosburgh, Stephen Graf, Ryan Huckeby, Richard<br />

Kacin, Ted Koch, Peter Lupsha, Robert Magill, Cholly<br />

McGlynn, Nick Miller, Nick Nichols, William Rahr,<br />

Adam Ratner, Jesse Riggleman, Jason Stewart,<br />

Robert Tammen, David Tawney, Lynda Tucker, Karl<br />

Van Calcar, Michael Verville, Barry Whitehill,<br />

BHA HEADQUARTERS<br />

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807<br />

www.backcountryhunters.org<br />

admin@backcountryhunters.org<br />

(406) 926-1908

Paul Kemper photo<br />

ARCTIC NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE, ALASKA<br />

BY MADDIE VINCENT<br />

IMAGINE A PLACE UNTOUCHED BY THE WORLD as we<br />

know it, where your eyes never find an end to the tundra, rivers,<br />

mountains. Where there is more wild than your mind can comprehend<br />

and the stillness moves every inch of your being into a<br />

state of calm isolation. No filters. No friend requests. Just raw life.<br />

Few places offer an escape more real than the Arctic National<br />

Wildlife Refuge, America’s 19.6 million-acre, multi-faceted<br />

crown jewel of the wildlife refuge system. The refuge is home to<br />

47 mammal, 42 fish and 201 bird species that span a wide range<br />

of arctic and subarctic ecosystems. But it’s the number with a dollar<br />

sign that’s grabbing people’s attention: $3.5 billion of total oil<br />

revenue the Trump administration believes is beneath the refuge’s<br />

Coastal Plain.<br />

However, these numbers are questionable, and the threat of oil<br />

drilling in the Arctic Refuge is not new. Conservationists have<br />

been fighting attempts to open the area to development since the<br />

late ’70s. But with the nation’s current political climate, coupled<br />

with the state of Alaska’s voted-on support, oil drilling is closer to<br />

becoming a reality.<br />

The Coastal Plain is a 1.5 million-acre biodiversity hotspot,<br />

known as the biological heart of the refuge. Oil drilling would<br />

disrupt the habitat of hundreds of species, including the calving<br />

grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. The Porcupine Caribou<br />

are the furthest migrating mammal herd on earth and are sacred<br />

to the native Gwich’in people.<br />

“Drilling in the refuge would impact the caribou and exacerbate<br />

climate change. The last thing we need is to put the pedal to<br />

the gas on climate change,” said Barry Whitehill, a BHA Legacy<br />

Partner and Alaska Chapter board member.<br />

Whitehill hunts the refuge every year, as well as guiding whitewater<br />

floats through the Brooks Range, one of the most remote<br />

areas within an already isolated refuge. This isolation draws a special<br />

kind of adventurer willing to be exposed to the elements.<br />

“When hunting in the refuge, you feel like you’re part of a process<br />

that’s been going on for eons,” Whitehill said. “It’s the last<br />

place you can feel what Lewis and Clark felt.”<br />

Hunting in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is unique for<br />

more than just its challenging landscape. In 1980, it was established<br />

as the refuge it is today under the Alaska National Interest<br />

Lands Conservation Act. Under ANILCA, the secretary of the<br />

interior had to identify special values of the refuge, from scenic<br />

to archeological, before a conservation plan could be considered.<br />

Roger Kaye, a 30-year U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service employee and<br />

the first BHA member from Alaska, helped develop hunting as<br />

one of these special values. He sees it as a key to the refuge’s protection.<br />

“Hunting is not recreation here. It’s not the place to just get<br />

your animal. It is a place to hunt in the wilderness and become a<br />

part of the natural scheme for a moment. Hunters feel it in their<br />

bones,” Kaye said.<br />

YOUR BACKCOUNTRY<br />

Kaye’s book, Last Great Wilderness: The Campaign to Establish<br />

the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (2006), details the movement<br />

to protect the Arctic Refuge and the conservationists who were instrumental<br />

in its designation. He believes the campaign was rooted<br />

in a growing fear for the technological future – and that hunters<br />

played a crucial role in proposing and supporting the refuge.<br />

“Some guys were concerned with the ethics of hunting and<br />

thought there ought to be a place that exemplifies a venerable<br />

hunting experience,” Kaye said. “So, this is the place where we<br />

draw the line. It’s a place of skill, effort and perseverance, not<br />

gadgets and vehicles.”<br />

Kaye says that because the refuge is renowned, it attracts a special<br />

segment of hunters, like Whitehill, who help maintain the<br />

wilderness character and ecological integrity. He believes that if<br />

the area is open to drilling, the quality of the wilderness and hunting<br />

experience will vanish.<br />

“People are concerned with the numbers of caribou and<br />

muskoxen that will be impacted, but the whole issue is not a<br />

numbers issue. The essential wildness is the concern because when<br />

you put oil fields out there, more than 10 generations of caribou<br />

will be displaced and will lose their migratory knowledge. Their<br />

wildness will be lost.”<br />

Now, almost 30 years after its establishment, ANILCA is getting<br />

a second look. In a government memo issued Aug. 11, 2017,<br />

the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service outlines its request from the secretary<br />

of the interior to amend the section of ANILCA that restricts<br />

oil exploration plan submissions in the Arctic Refuge. The<br />

department must respond to this request by Sept. 30, 2017, and<br />

if these changes are accepted, companies will be able to apply to<br />

explore oil drilling within the refuge’s boundaries.<br />

Dean Westlake, an Alaskan Inuit and state representative, supports<br />

oil exploration and helped draft a resolution in support of<br />

drilling that made it through to Washington, D.C., last March.<br />

Westlake believes that drilling on the Coastal Plain will help protect<br />

the refuge by getting more people to have a vested interest.<br />

“A lot of times, its the commercialization of something nearby<br />

that makes it pertinent to what you’d like to see in perpetuity,”<br />

Westlake said in a phone interview with BHA. “If we develop,<br />

now everyone is going to be in this to make sure this wildlife is<br />

secure. What company wants to get in there and be accused of<br />

wildlife extinctions?”<br />

Kaye and Whitehill disagree and are working with the Alaska<br />

BHA Chapter to educate people about the refuge and to broaden<br />

their support base, which they believe will help protect the refuge.<br />

“The biggest thing we’re trying to do is take people out, expose<br />

them to the refuge’s fragileness and exponentially increase the<br />

voices that say it’s not a barren wasteland – it should be fought for<br />

and protected,” Whitehill said.<br />

Maddie is a journalism graduate student, University of Montana<br />

soccer team member and Backcountry Journal intern.<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 5

BACKCOUNTRY<br />

JOURNAL<br />

The Magazine of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Fall 2017<br />

Volume XII, Issue IX<br />

Table of Contents<br />

Features<br />

Speechless: Dreams, Nightmares and Wyoming Moose 32<br />

By Jared Oakleaf<br />

My Chums 36<br />

By David Zoby<br />

For the Love of the Hunt 42<br />

By Natalie England<br />

Poem: Do the Math 45<br />

By George Wallace<br />

Sweat Equity 48<br />

By Mark Hurst<br />

A Conversation with Remi Warren 54<br />

By Ryan Hughes and Sam Lungren<br />

Dusan Smetana photo<br />

6 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017

Departments<br />

President’s Message 3<br />

True Grit<br />

Your Backcountry 5<br />

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska<br />

BHA Headquarters News 8<br />

Podcast & Blast, New Staffers, Photo Contest Winners, Elliott State Forest,<br />

National Monuments Review<br />

Backcountry Bounty 11<br />

Faces of BHA 13<br />

Katie DeLorenzo – Albuquerque, New Mexico<br />

Public Land Owner 15<br />

Sabinoso Wilderness, New Mexico<br />

Stream Access Now 16<br />

BHA members defend and improve sportsmen’s access to lakes in LA, SD and WA<br />

Backcountry Bistro 19<br />

Venison Chislic<br />

Beyond Fair Chase 21<br />

Fair Chase and Public Access<br />

Kids’ Corner 23<br />

Nuts About Fall<br />

Opinion 24<br />

Worth Fighting For<br />

Chapter News 26<br />

Instructional 56<br />

Eagle Eyes<br />

End of the Line 62<br />

Black Out Pack Out III<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 7

BHA HEADQUARTERS<br />

BHA PODCAST & BLAST<br />

IN JULY, BHA KICKED OFF BHA’s Podcast & Blast featuring the vocal and interviewing talents of Hal<br />

Herring, an award-winning journalist and contributing editor at Field & Stream. With each new podcast<br />

you can expect to hear conversations that are both entertaining and provocative. Guests so far have included<br />

Randy Newberg of On Your Own Adventures, Mike Schoby of Petersen’s Hunting, Steven Rinella of<br />

MeatEater, Anthony Licata of Field & Stream and conservation legend Jim Posewitz. As of mid-September<br />

the podcast had more than 100,000 downloads across iTunes, Stitcher and Podbean. It also can be found<br />

on YouTube.<br />

Hal has written for a wide range of publications including The Atlantic, The Economist, High Country<br />

News and Bugle. He’s a lifelong outdoorsman, mountaineer, hunter and fisherman and is well known for his<br />

deeply reported, thought-provoking stories and essays. Born and raised in northern Alabama, Hal moved to<br />

NEW FACES ON STAFF<br />

AS BHA CONTINUES TO GROW so does our staff of passionate<br />

conservationists. We are proud to introduce three new members<br />

of our team.<br />

CHRIS HENNESSEY, New York and Pennsylvania Public<br />

Lands Coordinator. Chris<br />

grew up in suburban Philadelphia<br />

with a passion for<br />

hunting, fishing, camping<br />

and nature. Now a resident<br />

of the outdoor mecca of State<br />

College, Pa., he is surrounded<br />

by the ridges and valleys<br />

of the Allegheny Mountains.<br />

There, and across the country,<br />

he enjoys many types of<br />

public land recreation with<br />

his wife, Tina, and their children PattyAnn and William.<br />

Chris spent most of his career in newspapers and public relations.<br />

His conservation ethic was honed while directing communications<br />

at a land trust in State College. He is excited to be on<br />

board at BHA and looks forward to working with members in to<br />

protect our precious woods and waters.<br />

JOSH KAYWOOD,<br />

Southeast Chapter Coordinator.<br />

Josh grew up<br />

backpacking, climbing and<br />

kayaking in the Blue Ridge<br />

Mountains, where he developed<br />

a passion for the<br />

outdoors. While attending<br />

college at the University of<br />

Mississippi he was introduced<br />

to a new landscape,<br />

the Mississippi Delta, where<br />

BHA RESPONDS TO LEAKED DOI NATIONAL MONUMENTS REPORT<br />

IN APRIL 2017, PRESIDENT TRUMP SIGNED an executive<br />

order instructing Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to review national<br />

monument designations from the past 21 years, a total of 27<br />

monuments. Zinke toured the country for four months visiting<br />

some of the monuments and speaking with proponents both for<br />

he fell in love with waterfowl hunting. The cypress swamps and<br />

fields of the delta provided a new lens through which to view the<br />

outdoors and inevitably led to his growing interests in small game<br />

hunting, as well as bowhunting whitetails and black bears.<br />

Before coming to BHA, Josh was an entrepreneur in healthcare,<br />

largely focusing on business development. Josh is a founding<br />

member of the Southeast Chapter and served as its first chair,<br />

which fostered a desire for a deeper level of commitment to the<br />

BHA mission.<br />

ALIAH ADAMS KNOPFF, Alberta Public Lands Coordinator.<br />

Aliah has always had a<br />

passion for wild places, especially<br />

the mountain backcountry<br />

of Western Canada<br />

and the U.S. She grew up<br />

hiking, backpacking, skiing<br />

and being outdoors with<br />

family. She is now passing<br />

on these traditions to her<br />

own children. Aliah was introduced<br />

to hunting in her<br />

early 20s, and she now uses<br />

her annual fall hunts to spend time in the mountains and ensure<br />

a freezer full of wild Alberta meat to fuel her family.<br />

Aliah’s interest in conservation led her to pursue undergraduate<br />

degrees in environmental science and international relations.<br />

Over the past six years, Aliah has been an environmental consultant<br />

working with Alberta’s large mammals, including mountain<br />

goats, bighorn sheep, cougars and bears.<br />

As the Alberta public lands coordinator with BHA, Aliah will<br />

focus her passion for the outdoors and conservation on fostering<br />

a collaborative network of individuals and organizations with a<br />

shared purpose of preserving the ecological integrity of Alberta’s<br />

public lands and wild spaces.<br />

and against the protection. In August, Zinke turned in his review<br />

to President Trump, but it was not made public.<br />

On Sept. 17, The Wall Street Journal published a leaked version<br />

of Zinke’s report. It outlined a plan for changing the management<br />

of 10 iconic American national monuments and reducing the<br />

8 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017

oundaries of at least four of them, including Utah’s Bears Ears<br />

and Grand Staircase-Escalante, Nevada’s Gold Butte and Oregon’s<br />

Cascade-Siskiyou. Within the report Zinke concluded that past<br />

presidents had overstepped their powers under the Antiquities Act<br />

to prevent economic activities such as grazing, timber production<br />

and mining rather than to protect specific objects as the act was<br />

intended. Zinke also suggested three new national monuments:<br />

one to cover roughly 130,000 acres in Montana next to Glacier<br />

National Park, the Badger-Two Medicine Area of the Lewis and<br />

Clark National Forest; the Jackson, Mississippi home of Medgar<br />

Evers, an NAACP field secretary who led protests against segregation<br />

and was murdered in 1963; and Camp Nelson, a Civil War<br />

Union Army supply depot in Kentucky.<br />

“While the administration’s report remains unconfirmed, vague<br />

details being reported at this time should concern public lands<br />

sportsmen and women,” said Land Tawney, BHA president and<br />

CEO. “If these recommendations reflect the Interior Department’s<br />

suggested course of action for Congress and President<br />

Trump, our public lands, waters, wildlife and outdoor traditions<br />

could be at risk.”<br />

OREGON’S ELLIOTT STATE FOREST TO REMAIN PUBLICLY ACCESSIBLE<br />

ESTABLISHED IN 1930, the Elliott State Forest was given to<br />

Oregon by the federal government to provide a sustainable source<br />

of school funding through timber harvest. Over time, divergent<br />

public interests led to a loss of revenue on the land and resulted<br />

in the state proposing its sale in fall 2015. BHA reacted quickly,<br />

launching a petition to protect the 93,000-acre forest that received<br />

over 4,000 signatures.<br />

In August Gov. Kate Brown signed S.B. 847 into law, transferring<br />

ownership of the Elliott from the school trust fund to<br />

an alternative state land management entity that does not have<br />

the same fiscal management constraints. The Oregon State Land<br />

Board had postponed ruling on the Elliott’s fate to give state lawmakers<br />

time to develop a plan that would keep the forest publicly<br />

accessible.<br />

“Finding creative ways to keep public lands in public hands<br />

is paramount in our fight against losing access to the lands and<br />

waters that we as sportsmen and women love,” said BHA Oregon<br />

Chair Ian Isaacson. “Just as important is engagement by the public.<br />

We must be active participants in the entire process, no matter<br />

how difficult, tiring and frustrating as it may be.”<br />

Headquarters News reported and written by Backcountry Journal<br />

intern Dakota Wharry.<br />

PUBLIC WATERS PHOTO CONTEST WINNERS<br />

First place: BJ Stone – “Montana Public Waters Handshake”<br />

Second place: Sara Schroeder – “Waterfall on<br />

Montana’s Rocky Mountain Front”<br />

Third place: Jason Hayes – “Teaching kids how to pack into the<br />

mountains, then catch, fillet and cook their own fish over an<br />

open fire is an unforgettable experience”<br />

Most Creative: Dave Quinn – ” Flippin’ out on a rare hot day on the lower Stikine River near<br />

the BC/Alaska boundary”<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 9

BACKCOUNTRY BOUNTY<br />

1<br />

3<br />

2<br />

4<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

Angler: Jessica Smail, BHA Member Species: Rainbow<br />

Trout State: Montana Method: Fly Rod Distance from<br />

nearest road: One mile Transportation: Foot<br />

Hunter: Bob Sorvaag, BHA Member<br />

Species: Mule Deer State: Idaho Method: Rifle<br />

Distance from nearest road: Two miles<br />

Transportation: Foot<br />

Hunter: Kyle Demmit, BHA Member Species: Ruffed<br />

Grouse State: Washington Method: Compound Bow<br />

Distance from nearest road: Five miles Transportation:<br />

Foot<br />

Hunter: Tom Martin, BHA Member Species: American<br />

Alligator State: Florida Method: Rod & Reel/Harpoon/<br />

Bang Stick Distance from nearest road: One mile<br />

Transportation: Boat<br />

Hunter: Allie D’Andrea, BHA Member Species: Pronghorn<br />

State: Wyoming Method: Compound Bow Distance<br />

nearest road: Two miles Transportation: Foot/Bike<br />

Send submissions to sam@backcountryhunters.org 5<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 11

12 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017 2016

FACES OF BHA<br />

KATIE DeLORENZO: Albuquerque, New Mexico<br />

Advertising Professional, NM Chapter Board Member, Train To Hunt Finalist<br />

HOW DID YOU START<br />

HUNTING?<br />

My dad is a really avid hunter<br />

so I grew up around it. He would<br />

bring animals home, and I was<br />

always aware of what he was doing,<br />

and he would show me all of<br />

the biology. If he brought a turkey<br />

home, we’d see what it had<br />

been eating and I would watch<br />

the butchering process happen,<br />

so that was kind of my first taste<br />

of it. I had been coaching soccer<br />

for 12 years, so I wasn’t really<br />

active and then got tired of<br />

coaching and blew out my knee<br />

and had four surgeries and my<br />

dad was retiring, so I thought,<br />

‘Oh my gosh I need to learn this<br />

stuff.’ So I went on a few hunts<br />

and got hooked. I went on a bighorn<br />

sheep hunt – it was a ewe<br />

hunt in the Latir Wilderness –<br />

and that was a life changing hunt<br />

for me. My dad and I hiked into<br />

the backcountry, and I killed<br />

an animal and carried it off the<br />

mountain on my back. It was a<br />

big moment because I’m 115 lbs,<br />

and my dad didn’t think I could<br />

carry the sheep. So that kind of<br />

challenge and that experience of<br />

having that solitude and hunting<br />

an animal that you have to carry<br />

out – it just changed everything<br />

for me, and I started thinking<br />

about it more like a sport and<br />

setting challenges and goals.<br />

WHAT ROLE DOES<br />

SOCIAL MEDIA PLAY IN<br />

MODERN HUNTING?<br />

To me, women hunting wasn’t<br />

that novel because my older sister<br />

is a very accomplished hunter.<br />

When I started putting my own<br />

stories out there, I really saw a<br />

need for education about what<br />

this lifestyle is about. There are<br />

many people who have no clue<br />

what is available to us. We have<br />

access to this amazing public land<br />

where you can go explore and see<br />

such diversity in the environment,<br />

species and even the exotics that<br />

have contributed to our hunting<br />

opportunity like ibex and oryx.<br />

There’s a need for education and<br />

advocates to make hunting approachable.<br />

Whether that’s a person<br />

who has never heard about it,<br />

or a female who wants to get into<br />

it and needs a buddy to go do archery<br />

with, my main goal is to be<br />

that source and speak about hunting<br />

in a responsible way and open<br />

those conversations to help people<br />

understand. There are also many<br />

who are not supportive of hunting,<br />

and if I can help justify it in<br />

a way that’s understandable, that’s<br />

a huge win for me. I’ve received<br />

pretty gnarly messages from anti-hunters.<br />

Education is the best<br />

thing we can be doing with social<br />

media to being responsible promoters<br />

of our lifestyle.<br />

WHAT ATTRACTED<br />

YOU TO BHA?<br />

Goodness, I would just say<br />

the energy around it. I keep a<br />

pretty close eye on everything<br />

that’s happening in the social<br />

realm, and to me, it just seemed<br />

like they have a lot of traction<br />

and momentum right now. The<br />

message really struck a chord<br />

with me, because I think being<br />

a native New Mexican and having<br />

a sense of reverence instilled<br />

in me since a young age for our<br />

public lands and wildlife, it was<br />

kind of like a wake up call as<br />

an adult: Here I am, enjoying<br />

all of this stuff, and it’s part of<br />

my heritage I feel very strongly<br />

about. Yet I’ve never been<br />

involved in advocating for it.<br />

So, really, it was the energy<br />

and momentum paired with an<br />

amazing group of people here<br />

in Albuquerque that I am confident<br />

will make a positive impact.<br />

I’ve worked with a lot of<br />

other organizations, and what I<br />

love about BHA is it’s an opportunity<br />

to make a real impact<br />

on my state. It’s important to<br />

me that future generations will<br />

be able to experience what I’ve<br />

experienced in the outdoors.<br />

WHAT IS THE BIGGEST<br />

THREAT TO HUNTING<br />

AND FISHING?<br />

I really feel at a basic level,<br />

that it’s just the loss of public<br />

lands either via access constraints<br />

or sale – and I wonder<br />

how I can help in fighting this. I<br />

work at one of the top ad agencies<br />

in the Southwest and I’m<br />

exposed to cutting edge communications<br />

on a daily basis, so<br />

I have the ability to find a synergy<br />

between my professional life<br />

and my biggest passion. I hope<br />

that by promoting hunting and<br />

bringing people on board with<br />

it, we can continue supporting<br />

our wildlife model and continue<br />

to be able to hunt and fish<br />

in America. We are all born<br />

with this right and only a few<br />

of us are fighting for it, and it<br />

could go away at any moment. I<br />

want to wake my generation up<br />

and say, ‘Hey, guys, it could go<br />

away at any moment. What can<br />

you be doing to help?’ Whether<br />

that’s taking a little kid fishing<br />

or hunting or getting someone<br />

involved so that they’re contributing,<br />

I think hunter recruitment<br />

is a really big topic for us<br />

right now. Who am I to enjoy<br />

all that New Mexico has to offer<br />

and then not fight on its behalf?<br />

If it really means so much<br />

to me, then I need to put my<br />

money where my mouth is.<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 13

14 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017

PUBLIC LAND OWNER<br />

Joel Gay photo<br />

SABINOSO WILDERNESS, NEW MEXICO<br />

BY RYAN HUGHES<br />

NEW MEXICO’S SABINOSO WILDERNESS is 16,030 acres<br />

of remote desert. Creeks lined with cottonwoods and willows flow<br />

through the bottoms of massive canyons cut into the landscape.<br />

Rocky cliffs loom over groves of pines and junipers where elk,<br />

mule deer, black bears and turkeys may be caught roaming. The<br />

Sabinoso is a landscape that is equally beautiful as it is unforgiving.<br />

It is also completely surrounded by private land, making it<br />

the only wilderness area that is inaccessible by overland travel.<br />

Legislation to designate the Sabinoso as wilderness failed several<br />

times before finding its way its into Omnibus Public Lands<br />

Management Act of 2009, where it recieved President Obama’s<br />

signature. But since its designation, the Sabinoso has remained effectively<br />

closed to any who wish to hunt, hike or explore. In 2016,<br />

the Wilderness Land Trust purchased the adjacent Rimrock Rose<br />

Ranch with plans to donate the ranch to the BLM. If accepted,<br />

this donation would allow passage into the Sabinoso through the<br />

southwestern boundary.<br />

A chorus of conservation organizations have since urged Secretary<br />

of the Interior Ryan Zinke to accept the donation of the<br />

3,314 acre ranch and open the Sabinoso. At press time, the secretary<br />

had not officially accepted the donation, athough he has<br />

indicated that he plans to do so.<br />

“I originally had concerns about adding more wilderness-designated<br />

area,” Zinke said in a statement. “However, after hiking and<br />

riding the land it was clear that access would only be improved if<br />

the U.S. Department of the Interior accepted the land and maintained<br />

the existing roadways.”<br />

As it stands, the only way to gain entry into the wilderness<br />

is by obtaining permission to cross a surrounding ranch or by<br />

miraculously dropping in from the sky. The lack of opportunity<br />

for hunting the Sabinoso leaves curiosity in the minds of many<br />

hunters. This makes any insights and experiences of hunting in<br />

the Sabinoso valuable. With a special draw archery mule deer tag<br />

in hand, New Mexico BHA member Joel Gay was able to secure<br />

permission to cross a surrounding private property. Though he<br />

was not sure what to expect there, Joel was enthused to have the<br />

opportunity to venture into an untouched landscape surrounded<br />

by both controversy and curiosity.<br />

“This is some really tough country. And it’s beautiful country.<br />

And it probably hasn’t been hunted in many years,” Joel said.<br />

What Joel found was rugged terrain and a desolate landscape.<br />

Trails were scarce. The September heat was practically begging<br />

him to pack up his gear and end his hunt, but the sight of fresh<br />

game tracks kept him on his toes as he glassed his way through the<br />

southern portion of the wilderness. Though he walked out of the<br />

Sabinoso emptyhanded, Joel gathered a rare perspective, piquing<br />

curiosity of what game might inhabit the northern regions.<br />

“It’s criminal that we have a wilderness area in the United States<br />

that’s currently landlocked with no access to it,” Joel said. “We<br />

need to get access to it. It will be great for anybody who wants to<br />

see some beautiful country and try to get a turkey in the spring<br />

or fall – and even knock themselves out by trying to get a deer.”<br />

Zinke made his statements following a visit to the Sabinoso,<br />

where he toured the area on horseback alongside Sens. Tom Udall<br />

and Martin Heinrich, both of New Mexico and vocal supporters<br />

of the Rimrock Rose Ranch donation. They were joined by BHA<br />

President and CEO Land Tawney. In a press release, Sens. Udall<br />

and Heinrich show appreciation for Zinke’s support, along with a<br />

recognition for the importance of public lands.<br />

“This is a major gain for New Mexico and would not be possible<br />

without the generosity of the Wilderness Land Trust and<br />

the dedication of the local community and sportsmen who have<br />

championed this effort for many years,” Heinrich said. “I am<br />

grateful that Secretary Zinke visited our state and recognizes just<br />

how special the Sabinoso truly is. Traditions like hunting, hiking,<br />

and fishing are among the pillars of Western culture and a thriving<br />

outdoor recreation economy.”<br />

BHA Southwest Chapter Coordinator Jason Amaro helped<br />

lead a grassroots campaign to secure to access to the Sabinoso<br />

Wilderness. He believes that Zinke deserves recognition for taking<br />

a pro access stance, but as a New Mexican hunter, he is still<br />

awaiting the land donation to be finalized.<br />

“If there was any doubt that sportsmen and women have a<br />

voice, the secretary’s announcement should settle that debate,” Jason<br />

said. “Together, hunters and anglers unanimously urged Secretary<br />

Zinke to do the right thing, and now we’ve taken a step to<br />

securing public access to one of New Mexico’s premier wilderness<br />

areas. We thank Sens. Heinrich and Udall for their leadership to<br />

get us here and look forward to continued partnership with Secretary<br />

Zinke and his staff to finalize this long awaited agreement.”<br />

As hunters dream of entrance into the Sabinoso, hunting season<br />

inches closer. Though Zinke’s plan to accept the land donation is<br />

worthy of applause, his actions will be the true testament to his<br />

commitment to both public lands and American sportsmen.<br />

Ryan is an intern at Backcountry Journal.<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 15

STREAM ACCESS NOW<br />

PUBLIC WATERS ACCESS:<br />

BHA members work to defend and improve sportsmen’s access<br />

to lakes in Louisiana, South Dakota, Washington<br />

BY MADDIE VINCENT<br />

IN OUR SUMMER 2017 ISSUE, Backcountry Journal highlighted<br />

water access concerns across the nation through narratives and<br />

a comprehensive chart of each state’s access laws. That data makes<br />

it clear that the battle for access to public waters is far from won.<br />

Legal issues continue to arise, making this issue an all-important<br />

focus for BHA. Right now, that focus is lake-heavy as we fight to<br />

protect and restore access in three states.<br />

CATAHOULA LAKE, LOUISIANA<br />

Catahoula is well-known as the largest freshwater lake in Louisiana.<br />

The 30,000-acre reservoir is one of the most important habitats<br />

for migrating ducks and shorebirds in the Mississippi Flyway.<br />

For over 100 years, people have hunted and fished Catahoula<br />

Lake, evidenced by the numerous duck blinds that decorate its<br />

shallow waters. Brett Herring of ShellShocked Guide Service has<br />

hunted the lake since he was 12 years old and says it still isn’t easy.<br />

“What makes it difficult to hunt Catahoula is the constant water<br />

fluctuations. You always gotta be on your toes and you gotta<br />

be willing to work. It’s a constant battle with Mother Nature,”<br />

Herring said.<br />

However, these water fluctuations are at the root of a bigger<br />

challenge than anything Herring has seen. A July district court<br />

ruling defined Catahoula as a floodplain wetland of Little River –<br />

not a lake – which changes more than just its name.<br />

Little River winds through the Catahoula Basin, historically a<br />

meandering stream for half of the year and an overflow for backed<br />

up tributaries for the other. In 1973, the Jonesville Lock and Dam<br />

was built, allowing greater control over a fluctuating waterbody.<br />

This turned Catahoula into a more permanent lake, while still<br />

allowing the flood-drain cycle responsible for the abundance of<br />

duck feed and other vegetation. But in Crooks v. State, the court<br />

deemed the dam unlawful expropriation of the Little River’s banks<br />

by the state, which owed the area’s private land owners almost $38<br />

million in damages and $4.5 million in oil and gas royalties.<br />

In Louisiana, the land below the ordinary high water mark of a<br />

lake is owned by the state, whereas the land between the ordinary<br />

high water and low water marks of a river can be privately owned.<br />

That means Catahoula’s river designation puts other non-permanent<br />

and seasonally flooded waterbodies, along with a dynasty of<br />

duck hunting, at risk of privatization. This has people like BHA’s<br />

Southeast Chapter Coordinator Josh Kaywood worried.<br />

“Because the Army Corps of Engineers built dams all over, almost<br />

every lake is a river dammed up,” Kaywood said. “If this case<br />

goes through, it sets a dangerous precedent that has the potential<br />

to affect waterbodies across the entire country.”<br />

The State of Louisiana filed an appeal to Crooks v. State that<br />

will most likely be heard next summer. Kaywood and his chapter<br />

are putting together a game plan to promote legislation in favor<br />

of public access. In the meantime, hunting and fishing on Catahoula<br />

will continue as before. And Herring plans to continue, as<br />

he’s always done.<br />

“If the appeal doesn’t go through, it’s definitely going to be a<br />

different way of life on Catahoula,” Herring said. “But, as lake<br />

hunters, we’ve always had to learn to adapt. It’s tough, but I like to<br />

think we’re some of the toughest duck hunters there are.”<br />

NON-MEANDERED LAKES, SOUTH DAKOTA<br />

Around the same time as Crooks v. State, the Open Waters<br />

Compromise (HB 1001) was enacted after a special session of the<br />

South Dakota legislature.<br />

The special session and resulting emergency legislation stems<br />

from the thousands of relatively new lakes in northeastern South<br />

Dakota. Up until about 20 years ago, this region was known<br />

for its mix of pastureland marshes and farmland. Then, the ’90s<br />

brought precipitation that didn’t stop. In ’96 and ’97, the state<br />

had one of the biggest snowfalls in history, and its melt-off helped<br />

permanently sink the meadows under 10 to 20 feet of water, creating<br />

lakes known as prairie potholes.<br />

Lakes in South Dakota fall in the public trust, meaning if they<br />

are legally accessible through a public road, they’re fair game.<br />

Northeastern South Dakota has a section line road almost every<br />

mile, so legal access is easy, and the new lakes have become recreational<br />

hotspots. South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks maintains<br />

91 active fisheries, mostly for walleye and perch, whose growth<br />

rates are extreme due to the great amount of vegetation. This vegetation<br />

also attracts thousands of waterfowl in the heart of the<br />

Central Flyway.<br />

But some landowners aren’t happy about sharing their land. In<br />

2003, their complaints and attempts to close the lakes influenced<br />

the South Dakota Supreme Court to order the state legislature to<br />

find a compromise between landowners and sportsmen. However,<br />

the legislature failed to act. So last spring, after more complaints<br />

and failed closures, the court ruled all non-meandered waters<br />

closed to public access. Their ruling drove the state legislature to<br />

assemble a study committee to take a closer look at South Dakota<br />

water law and come out with a band aid piece of legislation, HB<br />

1001.<br />

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, lakes across South Dakota<br />

were surveyed. If the lakes were at least 40 acres and of a permanent<br />

nature, they were considered “meandered lakes” held in the<br />

public trust. Most of the lakes in northeastern South Dakota are<br />

considered non-meandered because they are a result of excessive<br />

flooding and were not a part of the original survey. So, because<br />

these northeastern lakes are non-meandered, the state legislators<br />

decided in HB 1001, or the Open Water Compromise, that landowners<br />

may buoy off their sections of the lakes as private.<br />

Because this is a compromise, landowners have some restrictions.<br />

First, as part of the public trust, access to a water body is<br />

guaranteed, regardless of its designation. This means if a section<br />

line road runs right up to a lake, the public has 33 feet of access<br />

16 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017

on either side of the road’s center line. However, at the 34 foot<br />

line, landowners can post No Trespassing signs and buoys after<br />

notifying SDGFP. Second, in Section 8 of HB 1001, legislators<br />

identified 27 non-meandered lakes as open to the public due to<br />

their heavy and consistent recreational use. If landowners would<br />

like to buoy off their portions of a Section 8 lake, they would have<br />

to go through a petition process with SDGFP.<br />

As of early September, only four landowners have requested<br />

permission to close off lake areas. SDGFP Special Projects Coordinator<br />

Kevin Robling, whose focus is on HB 1001, is working<br />

closely with landowners and sportsmen to ensure the bill stays<br />

true to its name.<br />

“This is a unique situation because it is privately owned land<br />

under public trust waters, but we’re working with landowners<br />

closely. This is a very open and transparent process,” Robling said.<br />

Although HB 1001 doesn’t fully restore access, it buys more<br />

time for a state that’s already 90 percent privately owned and at<br />

risk of losing more of the little access it had to begin with. HB<br />

1001 will sunset in June 2018, meaning the state legislature must<br />

take action during the next session to make it permanent, or else<br />

it will disappear and the lakes will be closed to the public. Robling<br />

would like to see that sunset clause extended to three years so he<br />

has time to work with the bill and its commission.<br />

DRY LAKE, WASHINGTON<br />

While sportsmen and waterfront landowners are often pitted<br />

against each other in water access issues, the Washington BHA<br />

Chapter has shown it doesn’t have to be that way.<br />

Dry Lake, also known as Grass Lake, is a shallow home to largemouth<br />

bass, yellow perch, bluegill, crappie and brown bullheads<br />

near Chelan. The lake is one of 33 easements the Washington<br />

Department of Fish & Wildlife received as compensation for<br />

construction of the Rocky Reach and Rock Island dams on the<br />

Columbia River. Most of these easements are water banks surrounded<br />

by private property with no legal way in from the road,<br />

resulting in confusion and trespassing conflicts.<br />

Joe Bridges, a Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife<br />

biologist who helps resolve landowner conflicts, reached out to<br />

BHA and other organizations for financial support to turn a few<br />

of these easements into identifiable access points. Washington<br />

BHA Board Member Bob Mirasole toured the proposed sites with<br />

Bridges.<br />

“I drove out with Joe to see what the scope of the project was,<br />

and basically, it was a slam dunk type of thing,” Mirasole said.<br />

“There wasn’t any question as to why this wasn’t a good thing to<br />

support.”<br />

Bridges and Mirasole worked with landowners to create a primitive<br />

boat launch, parking lot and signage for the Dry Lake access.<br />

It’s been open for two months now and is the first leg of a three access<br />

project. Mirasole believes this project will set a precedent for<br />

future collaboration between the Washington BHA and WDFW<br />

to ensure public access across the state. He will continue to work<br />

with Bridges to raise funds for development of the Horse Lake<br />

Road and North Road access sites along the Wenatchee River, key<br />

steelhead and salmon fishing spots.<br />

Maddie is an intern at Backcountry Journal.<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 17

“<br />

As we head into the holidays, realize the great bounty that we<br />

collectively inherited didn’t happen by accident. Reflect on your<br />

”<br />

experiences in the woods and on the water and give back to<br />

those special places that have given you so much.<br />

WAYS<br />

YOU CAN<br />

GIVE<br />

BECOME A<br />

LEGACY PARTNER<br />

BECOME A LIFE<br />

MEMBER<br />

- LAND TAWNEY<br />

PRESIDENT AND CEO<br />

PLANNED GIVING<br />

BEQUESTS<br />

WORKPLACE<br />

MATCH<br />

CHARITABLE<br />

ANNUITIES<br />

IRA ROLLOVER<br />

LIFE MEMBER<br />

PREMIUMS FROM<br />

KIMBER FIREARMS<br />

SEEK OUTSIDE TENTS<br />

ORVIS FLY RODS<br />

JACKSON KAYAKS<br />

18 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017<br />

CONSERVATION LEGEND JIM POSEWITZ, AUTHOR OF BEYOND FAIR CHASE, WITH HIS SON CIRCA 1982<br />

WELCOME NEW BHA LIFE MEMBERS!<br />

Michael Guran<br />

Charles Smith<br />

Daniel Wieking<br />

Mike Doden<br />

Jon Gillespie-Brown<br />

Nicholas Maus<br />

Matt Little<br />

Joshua Watts<br />

Stephen Mason<br />

Luke Moffat<br />

Gretchen Rebarchak<br />

Montana Raft Frames<br />

Bart Gliatta<br />

Mike Filkowski<br />

Brian Book<br />

Christian Miller<br />

Stacey Roth<br />

Dennis Dunn<br />

Craig Zeinstra<br />

Joe Stribley<br />

Mark Rasmussen<br />

Josh Rhodes<br />

Karl Malcom<br />

Joe Kondelis<br />

Brandon Sheltrown<br />

Matthew Lee<br />

Nathan Zientek<br />

Bruce Sillers<br />

Gabriel Halley<br />

Scott Harton<br />

Ajax Moody<br />

P. Francois Smuts<br />

Adrian Castelli<br />

Chris Davis<br />

Tim Fontaine<br />

Russell Hrisbeck<br />

Michael Tollefsrud<br />

John Lynn<br />

John Sullivan<br />

Daniel Laughlin<br />

Erik Bentley<br />

Call GRANT ALBAN at 406-926-1908 OR<br />

Visit www.backcountryhunters.org/donate

BACKCOUNTRY BISTRO<br />

DEER CHISL C<br />

Read more<br />

about out-ofkitchen<br />

food prep at<br />

backcountry<br />

hunters.org<br />

BY SPENCER NEUHARTH<br />

WE RETURNED TO CAMP EAGER TO EAT something that<br />

wasn’t another uninspiring ham sandwich. Though only Day Two<br />

of the hunt, the heavy gambrel next to the cabin meant venison<br />

on the menu. Hungry as we were tired, it was easy to decide on<br />

supper. South Dakotans know the right way to do it.<br />

As I peeled a backstrap from the mule deer, my friend Logan<br />

dumped some olive oil into a fire-lit Dutch oven. The pot was<br />

crackling as I cubed the loin. I sank the small chunks of meat, covered<br />

in Cavender’s Seasoning, into the oil not long after. In about<br />

the time it takes to nuke a bowl of ramen, the meal was served.<br />

“Chislic is the food God eats. We’re just fortunate enough that<br />

he shares some with us,” Logan muttered as we sat by the fire.<br />

Chislic, typically fried mutton on a stick, is only known among<br />

the select few who call South Dakota home. Although unheard of<br />

elsewhere, it is wildly popular in my home state. So much so that<br />

the area’s largest newspaper declared it “South Dakota’s favorite<br />

food.” The region’s largest magazine deemed the southeastern corner<br />

of the state “Chislic Circle.”<br />

It’s within that Chislic Circle that the dish arose. The name<br />

comes from the Turkic word “shashlik,” meaning cubed red meat<br />

on a stick – the same root as shish kebab. It’s believed that chislic<br />

was first prepared here in the 1870s by an immigrant from the<br />

Crimean Peninsula of Eastern Europe. Since then, it’s become a<br />

staple for the Mount Rushmore State.<br />

In Freeman, population 1,300, sticks of chislic are served by<br />

the dozen, and the the town literally goes through hundreds of<br />

thousands of sticks a year. One bar, Papa’s, estimates that they<br />

sometimes serve up to 3,000 sticks a week. Not far away is the<br />

Turner County Fair, which sells nearly 10,000 sticks a day during<br />

the five-day gathering.<br />

Chislic is almost always served as mutton or lamb, but what<br />

small town you’re in plays a role in how your chislic arrives. In<br />

Yankton, chislic comes with a side of toast. In Menno, it’s served<br />

with saltines. In Freeman, it’s deep fried with slices of onion. In<br />

Sioux Falls, it’s grilled on a set of small kebab sticks.<br />

There are some chislic sins that Dakotans are mindful of: You<br />

shall not marinade it, overcook it or leave any leftovers. Marinating<br />

chislic takes away from the simplicity and trends away from<br />

the 1870s-inspired meal. Overcooking it robs the meat of tenderness,<br />

which is easily done with such small portions. Leftovers<br />

won’t do justice the second time around, as flavor and juiciness are<br />

unmatched with fresh, hot chislic.<br />

Although chislic is almost always made with sheep in restaurants,<br />

some people use beef or venison. In those rare instances, it’s<br />

vehemently referred to as “beef chislic” or “deer chislic.”<br />

Deer chislic is as versatile as mutton, which is what makes<br />

it such a great camp meal. Any deer lodge or tent site should<br />

have access to a grill, stove or fire, making this dish ideal for the<br />

culinarily limited places hunters often find themselves.<br />

Chislic should be sliced into small, un-uniform pieces that are<br />

roughly as wide as a quarter and thick as your thumb. The best<br />

cuts for venison are the backstraps and round roasts, as these offer<br />

the biggest hunks of meat that require the least amount of trimming.<br />

Like mutton, it’s acceptable to serve it loose or on a stick.<br />

Either way you do it, deer chislic is so simple and delicious that<br />

it’s sure to be a hit at any deer camp. In my opinion, it’s about<br />

time for this secret dish to make its way beyond the borders of<br />

South Dakota.<br />

FRIED DEER CHISLIC<br />

Half of a backstrap, cubed<br />

Two onions, sliced<br />

Garlic powder<br />

Black pepper<br />

Salt<br />

Olive oil<br />

In a Dutch oven, heat up just enough oil to cover the meat.<br />

Once the oil is hot, drop in the onions for 1 minute.<br />

With the onions still in the Dutch oven, drop the chislic in for<br />

2 minutes.<br />

Remove both the onions and chislic, transferring to a paper<br />

towel for blotting before serving.<br />

Generously apply garlic powder, black pepper and salt.<br />

GRILLED DEER CHISLIC<br />

Half a backstrap, cubed<br />

Cavender’s Seasoning<br />

Kebab sticks<br />

Thread the chislic cubes on small kebab sticks, close enough to<br />

almost touch each other.<br />

On a hot grill, cook the chislic for three minutes, or until you<br />

see the sticks start to char.<br />

Remove from grill and generously apply Cavender’s Seasoning.<br />

Spencer is an outdoor writer and photographer out of South Dakota.<br />

He joined BHA in 2017 upon the state getting its own chapter.<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 19

20 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017

BEYOND FAIR CHASE<br />

Daniel Wilde photo<br />

BY JAN E. DIZARD<br />

FOR ROUGHLY TWO-THIRDS OF THE 20TH CENTURY,<br />

hunters and fishers were the bedrock of conservation. But beginning<br />

in the early 1970s, the ground shifted. The accomplishments<br />

of the conservation movement, to which hunters contributed<br />

mightily, began to pale in the face of new environmental<br />

issues and a new environmental movement that had priorities<br />

not centered on restoration of game and fish and the habitats on<br />

which they depend. Indeed, protection of wildlife and opposition<br />

to management practices that enhanced wildlife habitat became<br />

dominant. Hunters and the new environmental movement diverged.<br />

The result, sadly, has weakened both. Both now face a<br />

different challenge as serious as the one we faced a century ago.<br />

Strong political forces mean to take advantage of the split between<br />

hunters and environmentalists and are determined to turn the<br />

public lands over to the states. As BHA has made clear, should<br />

this happen, hunting and fishing opportunities will be curtailed.<br />

More than access is at stake in the threat to public lands. Broad<br />

access to hunting and fishing opportunities is crucial to sustaining<br />

the ethic of fair chase. A page from my own experience reveals the<br />

link between access and a robust hunting ethic.<br />

When I was new to western Massachusetts and hadn’t had time<br />

to get my bearings, I hunted the only public lands open to hunting:<br />

state-run management areas stocked with pheasants. Crowds<br />

of hunters assembled in designated parking lots, waiting for the<br />

legal shooting hour. Then, like an invading army, hunters and<br />

dogs streamed into the field. I witnessed heated arguments over<br />

whose dog had first pointed a pheasant and whose shot, among<br />

a volley of shots, brought the bird down. It was a scene designed<br />

to bring out the worst in us, not the best. To be sure, even in<br />

those less than ideal situations most hunters were respectful of<br />

others and mindful of elementary safety. But frayed nerves and an<br />

inevitable sense of competition made it likely that tempers would<br />

flare and, even more troubling, that ill-considered shots would<br />

be taken.<br />

In the East, where I live, private lands dwarf public lands. But<br />

FAIR CHASE AND PUBLIC ACCESS:<br />

JOINED AT THE HIP<br />

more and more private land is being put off-limits to hunting.<br />

Each year, more private lands are decorated with signs declaring<br />

the land closed to public access. This is creating a cascade<br />

of unwelcome effects. Crowding on what remains open is first.<br />

The crowding in turn degrades the habitat over time and requires<br />

more and more investment in upkeep, straining agency budgets.<br />

As noted, the experience of hunting is diminished. Men and<br />

women are drawn to hunting for a variety of reasons, but being<br />

in close proximity to hundreds of other hunters is not usually one<br />

of them. Hunters give up, license revenues decline and state agencies<br />

are further cash strapped. But also – and this is crucial – the<br />

ethic of fair chase is weakened by the crowding and the race to<br />

get to the bird first. Finally, those who can afford leases or private<br />

clubs will do so and, in effect, withdraw support for maintaining<br />

broad public access. This re-commercialization of hunting is well<br />

underway all across the country, and it threatens to undermine<br />

the fundamentally democratic character of the North American<br />

Model of hunting and wildlife management.<br />

It is well we remember that our hunting heritage has been<br />

based upon a fundamental principle: the Public Trust Doctrine.<br />

The doctrine holds that some resources, among them wildlife, are<br />

held in common. Like the air we breathe, our wildlife belongs to<br />

everyone. Democracy is not simply about voting and politics. It is<br />

about distributing, not restricting, access to those things we hold<br />

in common, among them public lands and the recreational opportunities<br />

they afford. If the opportunity to hunt or fish is constricted<br />

by restricting access or, what amounts to the same thing,<br />

degrading habitat by mining, drilling, loosely regulated grazing<br />

and rapacious logging, the hard-won commitment to fair chase<br />

will be sorely weakened as hunters are forced to hunt in ever fewer<br />

and more crowded public management areas. Need I add that the<br />

hunting behavior that will ensue will make hunters an easy target<br />

for those who oppose hunting?<br />

Jan is a board member of Orion: The Hunters’ Institute and a life<br />

member of BHA. A retired professor, he splits his time between western<br />

Massachusetts and northern California.<br />

This Backcountry Journal department is brought to you by Orion:<br />

The Hunter’s Institute, a nonprofit and BHA partner dedicated to<br />

advancing hunting ethics and wildlife conservation. To learn more,<br />

visit orionhunters.org. To comment on and discuss this article and<br />

others, go to backcountryhunters.org/fair_chase.<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 21

SUMMER SCAVENGER HUNTERS<br />

Hazel Larson admiring her catch<br />

The BHA Kid’s<br />

Summer Scavenger<br />

Hunt Extravaganza<br />

was another great<br />

success! Kids were<br />

instructed to complete<br />

tasks listed in<br />

Backcountry Journal and<br />

find items from a list,<br />

then send in their photos<br />

to win a Public Land<br />

Owner T-shirt!<br />

Ryan Olson searching for fish food before snoozing on the way home Colton Dukehart inspecting his found feather<br />

Eleanor and Stewart Davis preparing for their scavenger hunt<br />

Sam McCaulou hiking on his public lands<br />

Walker Larson (above) catching a fish, and Tristan Mieczkowski (below) cooking a fish

KIDS’ CORNER<br />

NUTS<br />

ABOUT FALL<br />

Michael Furtman photo<br />

BY KEN KEFFER<br />

THE FORESTS ARE CHANGING COLORS and the leaves will<br />

be dropping soon. Football season is here, and so is hunting season!<br />

It is an exciting time of year to be in the backyard and in<br />

the backcountry. The temperatures might be dropping, but the<br />

fall is heating up for the animals. They are busy finding food and<br />

preparing for winter.<br />

FILLING UP<br />

Fall can be frantic for many critters. Have you ever watched the<br />

squirrels in your neighborhood? Sure, you see them coming and<br />

going all year long, but sit and study them for 5-10 minutes in the<br />

fall. Observing animal behaviors will make you a better naturalist<br />

and a better hunter. In autumn, squirrels scurry about with added<br />

urgency. They collect seeds and nuts and store them up for winter.<br />

Gray squirrels tend to bury nuts throughout their entire home<br />

range. Red squirrels generally collect their bounty in one location.<br />

If you’re out hunting in the woods, look for red squirrel middens.<br />

These are piles of pine cone scales. The squirrels store up a<br />

supply of cones and then sit on their favorite perch snacking away.<br />

They chew into the cones to get to the pine nuts (or spruce nuts<br />

or fir nuts) and the cone scales get tossed aside like peanut and<br />

sunflower seed shell. This leaves behind a messy pile of cone scales<br />

that can be many inches deep. If you’ve found a midden while<br />

squirrel hunting, you’ll know you are in the right spot.<br />

ABUNDANT ACORNS<br />

Acorns are the seeds of oak trees. They are a treat for a bunch of<br />

creatures large and small. There are about 90 species of oak native<br />

to North America. Oak trees take years to mature before they<br />

start producing acorns. Some species make acorns after 20 years.<br />

Others can take 50 years or more before the first acorns appear.<br />

The amount of acorns made by each tree is different from year to<br />

year. Great weather leads to large amounts of acorns. These mast<br />

years become an all-you-can-eat buffet for everything from deer<br />

mice to white-tailed deer.<br />

The acorn caps can make a great whistle. Pinch it between your<br />

pointer fingers and your thumbs while holding the top away from<br />

you. Press your thumbnails to your lower lip and give it a blow.<br />

Adjust until you get a pure whistle. Even if you don’t have an oak<br />

tree around, you should be able to find some fall leaves. Collect<br />

a few and examine them closely. Can you tell the top from the<br />

bottom? How many differently colored leaves can you find? Find<br />

a leaf that has at least three colors on it.<br />

DUCK, DUCK, GOOSE<br />

A few duck species will munch on acorns. Wood ducks especially<br />

seem to bob for acorns in shallow water like you might bob<br />

for apples. Woodies, along with mallards, will munch on acorns<br />

right from the forest floor, too. In the fall, Canada geese also will<br />

get in on the acorn meal plan. So how do ducks and geese eat such<br />

a hard food? They swallow acorns whole. Then, with the help of<br />

a special organ called a gizzard, they crush the acorns. Waterfowl<br />

eat small pebbles of rock that are stored in the gizzard. This helps<br />

grind up hard foods. These birds are the original dine and dashers.<br />

They eat up as quickly as they can before moving to a more<br />

protected area to finish digesting. However, acorns are not on the<br />

menu for much of the year. Instead, they are just a fall treat for<br />

waterfowl.<br />

Fall is the season for wildlife to fatten up for winter. It’s also the<br />

time of year when hunters harvest their bounties to feast upon.<br />

Next time you’re in the woods, thank the trees. Their seeds and<br />

nuts help feed the animals each fall.<br />

Author, naturalist and BHA member Ken Keffer grew up hunting<br />

and fishing in Wyoming. He has written seven books connecting<br />

families to nature, plus the Hiking Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains<br />

guidebook. Find him at kenkeffer.net.<br />

FALL 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 23

OPINION<br />

Dale Spartas photo<br />

WORTH FIGHTING FOR<br />

BY REID BRYANT<br />

“WE ABUSE LAND BECAUSE WE REGARD IT AS A COMMODITY BELONGING TO US. WHEN WE SEE LAND AS A<br />

COMMUNITY TO WHICH WE BELONG, WE MAY BEGIN TO USE IT WITH LOVE AND RESPECT.”<br />

– Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac<br />

This passage from Leopold’s seminal conservation work alludes<br />

knowingly to what remains essential about being a hunter. Central<br />

to the process of becoming a hunter, and central to the identity<br />

found upon arrival, is the community of which Leopold speaks.<br />

This is not just a community of peers, but a community of all<br />

things in nature. When I became a hunter, I ceased to walk over<br />

the land. As a hunter, I became an element of that land, a cog in<br />

a remarkable living machine that is as old as the Earth itself – and<br />

as timeless. Leopold spent a career reflecting on this community<br />

and the role of humans within it. He sat and he watched “like a<br />

mountain,” and he learned by reflective observation. He also took<br />

up a gun each autumn and went hunting, learning a bit more<br />

about himself, and his human ecology, than he’d known before.<br />

Aldo went on to assert that, “In short, a land ethic changes the<br />

role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community<br />

to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members,<br />

and also respect for the community as such.” This<br />

construct is somewhat hard to grasp for most folks, simply because<br />

humans have the capacity, the resources, the vision and the<br />

ingenuity to assert dominance over a natural system at will. We<br />

do so each and every day as we increasingly live outside of nature.<br />

It is why we have survived and flourished, and it is also why, you<br />

might say, we have become disenchanted with and disconnected<br />

from our natural world. We have lost our place in the community<br />

that allowed us a sense of place since time immemorial, and we’ve<br />

in turn become confused about our role.<br />

It is ironic, therefore, that taking up a gun in fall to shoot a bird<br />

or a deer might serve to re-establish a fundamental philosophical<br />

and ecological order. It is ironic that deploying a man-made machine<br />

and ostensibly asserting dominance over a wild creature,<br />

or even more paradoxically a non-endemic, one-time-stocked<br />

creature, could help me regain a sense of myself. It is most ironic,<br />

I might add, that in light of the availability of pre-packaged,<br />

pre-cooked, profoundly inexpensive food I would ever choose to<br />

spend time and money shooting at a piece of meat that, more<br />

often than not, disappears unscathed into the backdrop. But I do<br />

this and love doing it and I seek to do it again. In turn, it makes<br />

me care a little more about the creatures I seek, and the places in<br />

which I seek them.<br />

I am neither a student of psychology nor a student of philosophy,<br />

so I can’t authoritatively say why I am drawn to hunting<br />

or what it means that I am compelled in this way. I assume that<br />

humans were hunters for so long that it became a part of our<br />

wiring, and only fairly recently did we disconnect from a personal<br />

relationship with food acquisition. I can say, and with some confidence,<br />

that in becoming a hunter I was afforded an awareness of a<br />

new community, or perhaps a forgotten community, and one that<br />

my ancestors knew well. My friend Kurt Rinehart, who is one of<br />

the finest naturalists I know, often says that in being a hunter he<br />

is offered a seat at the table. I love this analogy. It is resonant on<br />

a level that both speaks to basic human need, and to essential human<br />

consciousness. As a hunter, in North America anyway, your<br />

table is laid with a host of wild foods so delicate and rare that<br />

they are, in themselves, great treasures. These foods are offered<br />

24 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2017

in quantity for the cost of a hunting license and some wonderful<br />

days spent afield. Beside you at the table are people who, like you,<br />

see value in being outdoors, in taking responsibility for a linear<br />

connection to the food they eat and the realities of that. There is<br />

a shared identity at the table and a shared pride in place. There is,<br />

at root, community. But a seat at the table offers far more lasting<br />

value than simply a fine piece of meat, served in good company.<br />