Viva Lewes Issue #147 December 2018

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

BRICKS AND MORTAR<br />

Myth of bricks<br />

Mathematical tiles<br />

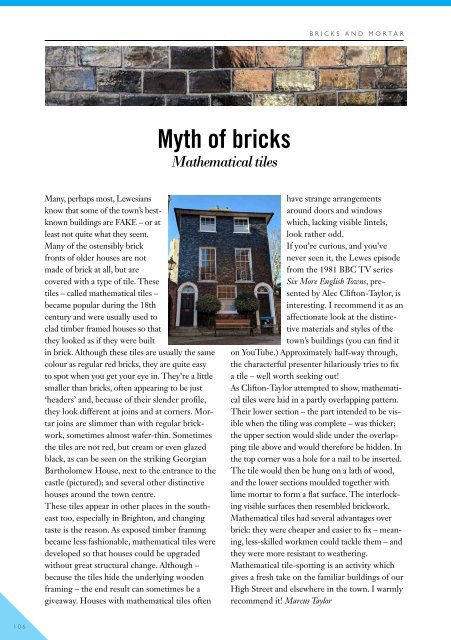

Many, perhaps most, <strong>Lewes</strong>ians<br />

know that some of the town’s bestknown<br />

buildings are FAKE – or at<br />

least not quite what they seem.<br />

Many of the ostensibly brick<br />

fronts of older houses are not<br />

made of brick at all, but are<br />

covered with a type of tile. These<br />

tiles – called mathematical tiles –<br />

became popular during the 18th<br />

century and were usually used to<br />

clad timber framed houses so that<br />

they looked as if they were built<br />

in brick. Although these tiles are usually the same<br />

colour as regular red bricks, they are quite easy<br />

to spot when you get your eye in. They’re a little<br />

smaller than bricks, often appearing to be just<br />

‘headers’ and, because of their slender profile,<br />

they look different at joins and at corners. Mortar<br />

joins are slimmer than with regular brickwork,<br />

sometimes almost wafer-thin. Sometimes<br />

the tiles are not red, but cream or even glazed<br />

black, as can be seen on the striking Georgian<br />

Bartholomew House, next to the entrance to the<br />

castle (pictured); and several other distinctive<br />

houses around the town centre.<br />

These tiles appear in other places in the southeast<br />

too, especially in Brighton, and changing<br />

taste is the reason. As exposed timber framing<br />

became less fashionable, mathematical tiles were<br />

developed so that houses could be upgraded<br />

without great structural change. Although –<br />

because the tiles hide the underlying wooden<br />

framing – the end result can sometimes be a<br />

giveaway. Houses with mathematical tiles often<br />

have strange arrangements<br />

around doors and windows<br />

which, lacking visible lintels,<br />

look rather odd.<br />

If you’re curious, and you’ve<br />

never seen it, the <strong>Lewes</strong> episode<br />

from the 1981 BBC TV series<br />

Six More English Towns, presented<br />

by Alec Clifton-Taylor, is<br />

interesting. I recommend it as an<br />

affectionate look at the distinctive<br />

materials and styles of the<br />

town’s buildings (you can find it<br />

on YouTube.) Approximately half-way through,<br />

the characterful presenter hilariously tries to fix<br />

a tile – well worth seeking out!<br />

As Clifton-Taylor attempted to show, mathematical<br />

tiles were laid in a partly overlapping pattern.<br />

Their lower section – the part intended to be visible<br />

when the tiling was complete – was thicker;<br />

the upper section would slide under the overlapping<br />

tile above and would therefore be hidden. In<br />

the top corner was a hole for a nail to be inserted.<br />

The tile would then be hung on a lath of wood,<br />

and the lower sections moulded together with<br />

lime mortar to form a flat surface. The interlocking<br />

visible surfaces then resembled brickwork.<br />

Mathematical tiles had several advantages over<br />

brick: they were cheaper and easier to fix – meaning,<br />

less-skilled workmen could tackle them – and<br />

they were more resistant to weathering.<br />

Mathematical tile-spotting is an activity which<br />

gives a fresh take on the familiar buildings of our<br />

High Street and elsewhere in the town. I warmly<br />

recommend it! Marcus Taylor<br />

106