Aziz Art January 2019

History of art(west and middle east)- contemporary art ,art ,contemporary art ,art-history of art ,iranian art ,iranian contemporary art ,famous iranian artist ,middle east art ,european art

History of art(west and middle east)- contemporary art ,art ,contemporary art ,art-history of art ,iranian art ,iranian contemporary art ,famous iranian artist ,middle east art ,european art

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Aziz</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>January</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Abbas Kowsari<br />

Parastou Forouhar<br />

Louise Bourgeois

1-Louise Bourgeois<br />

16-Parastou<br />

Forouhar<br />

21-Abbas Kowsari<br />

Director: <strong>Aziz</strong> Anzabi<br />

Editor : Nafiseh<br />

Yaghoubi<br />

Translator : Asra<br />

Yaghoubi<br />

Research: Zohreh Nazari<br />

http://www.aziz-anzabi.com

Louise Joséphine Bourgeois 25<br />

December 1911 – 31 May 2010<br />

was a French-American artist.<br />

Although she is best known for<br />

her large-scale sculpture and<br />

installation art, Bourgeois was also<br />

a prolific painter and printmaker.<br />

She explored a variety of themes<br />

over the course of her long career<br />

including domesticity and the<br />

family, sexuality and the body, as<br />

well as death and the<br />

subconscious.<br />

These themes connect to events<br />

from her childhood which she<br />

considered to be a therapeutic<br />

process.<br />

Although Bourgeois exhibited with<br />

the Abstract Expressionists and her<br />

work has much in common with<br />

Surrealism and Feminist art, she<br />

was not formally affiliated with a<br />

particular artistic movement.<br />

Early life<br />

Bourgeois was born on 25<br />

December 1911 in Paris, France.<br />

She was the second child of three<br />

born to parents<br />

Joséphine Fauriaux and Louis<br />

Bourgeois. She had an older sister<br />

and a younger brother.Her parents<br />

owned a gallery that dealt primarily<br />

in antique tapestries. A few years<br />

after her birth, her family moved<br />

out of Paris and set up a workshop<br />

for tapestry restoration below their<br />

apartment in Choisy-le-Roi, for<br />

which Bourgeois filled in the<br />

designs where they had become<br />

worn.<br />

The lower part of the tapestries<br />

were always damaged which was<br />

usually the characters' feet and<br />

animals' paws. Many of Bourgeois's<br />

works have extremely fragile and<br />

frail feet which could be a result of<br />

the former.<br />

In 1930, Bourgeois entered the<br />

Sorbonne to study mathematics<br />

and geometry, subjects that she<br />

valued for their stability, saying "I<br />

got peace of mind, only through<br />

the study of rules nobody could<br />

change."<br />

Her mother died in 1932, while<br />

Bourgeois was studying<br />

mathematics. Her mother's death<br />

inspired her to abandon<br />

mathematics and to begin studying<br />

art.<br />

1

She continued to study art by<br />

joining classes where translators<br />

were needed for English-speaking<br />

students, in which those<br />

translators were not charged<br />

tuition. In one such class Fernand<br />

Léger saw her work and told her<br />

she was a sculptor, not a painter.<br />

Bourgeois graduated from the<br />

Sorbonne 1935. She began<br />

studying art in Paris, first at the<br />

École des Beaux-<strong>Art</strong>s and<br />

École du Louvre, and after 1932<br />

in the independent academies<br />

of Montparnasse and<br />

Montmartre such as Académie<br />

Colarossi, Académie Ranson,<br />

Académie Julian, Académie de la<br />

Grande Chaumière and with<br />

André Lhote, Fernand Léger, Paul<br />

Colin and Cassandre.<br />

Bourgeois had a desire for firsthand<br />

experience, and frequently<br />

visited studios in Paris, learning<br />

techniques from the artists and<br />

assisting with exhibitions.<br />

Bourgeois briefly opened a print<br />

store beside her father's tapestry<br />

workshop. Her father helped her<br />

on the grounds that she had<br />

entered into a commerce-driven<br />

profession.<br />

Bourgeois emigrated to New York<br />

City in 1938. She studied at the <strong>Art</strong><br />

Students League of New York,<br />

studying painting under Vaclav<br />

Vytlacil, and also producing<br />

sculptures and prints.<br />

"The first painting had a grid: the<br />

grid is a very peaceful thing<br />

because nothing can go wrong ...<br />

everything is complete. There is no<br />

room for anxiety ... everything has<br />

a place, everything is welcome."<br />

Bourgeois incorporated those<br />

autobiographical references to her<br />

sculpture Quarantania I, on display<br />

in the Cullen Sculpture Garden at<br />

the Museum of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s, Houston.<br />

Middle years<br />

For Bourgeois the early 1940s<br />

represented the difficulties of a<br />

transition to a new country and the<br />

struggle to enter the exhibition<br />

world of New York City. Her work<br />

during this time was constructed<br />

from junkyard scraps and driftwood<br />

which she used to carve upright<br />

wood sculptures.

The impurities of the wood were<br />

then camouflaged with paint,<br />

after which nails were employed<br />

to invent holes and scratches in<br />

the endeavor to portray some<br />

emotion. The Sleeping Figure is<br />

one such example which depicts a<br />

war<br />

figure that is unable to face the<br />

real world due to vulnerability.<br />

Throughout her life, Bourgeois's<br />

work was created from revisiting<br />

of her own troubled past as she<br />

found inspiration and temporary<br />

catharsis from her childhood years<br />

and the abuse she suffered from<br />

her father. Slowly she developed<br />

more artistic confidence, although<br />

her middle years are more opaque,<br />

which might be due to the<br />

fact that she received very little<br />

attention from the art world<br />

despite having her first solo show<br />

in 1945.She became an American<br />

citizen in 1951.<br />

In 1954, Bourgeois joined the<br />

American Abstract <strong>Art</strong>ists Group,<br />

with several contemporaries,<br />

among them Barnett Newman<br />

and Ad Reinhardt. At this time she<br />

also befriended the artists Willem<br />

de Kooning, Mark Rothko,<br />

and Jackson Pollock.<br />

As part of the American Abstract<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ists Group, Bourgeois made the<br />

transition from wood and upright<br />

structures to marble, plaster and<br />

bronze as she investigated concerns<br />

like fear, vulnerability and loss of<br />

control. This transition was a<br />

turning point. She referred to her<br />

art as a series or sequence closely<br />

related to days and circumstances,<br />

describing her early work as the<br />

fear of falling which later<br />

transformed into the art of falling<br />

and the final evolution as the art of<br />

hanging in there. Her conflicts in<br />

real life empowered her to<br />

authenticate her experiences and<br />

struggles through a unique art<br />

form. In 1958, Bourgeois and her<br />

husband moved into a terraced<br />

house at West 20th Street, in<br />

Chelsea, Manhattan, where she<br />

lived and worked for the rest of her<br />

life.<br />

Despite the fact that she rejected<br />

the idea that her art was feminist,<br />

Bourgeois's subject was the<br />

feminine. Works such as Femme<br />

Maison (1946-1947), Torso selfportrait<br />

(1963-1964), Arch of<br />

Hysteria (1993), all depict the<br />

feminine body.

In the late 1960's, her imagery<br />

became more explicitly sexual as<br />

she explored the relationship<br />

between men and women and the<br />

emotional impact of her troubled<br />

childhood.<br />

Sexually explicit sculptures such<br />

as Janus Fleuri, (1968) show she<br />

was not afraid to use the female<br />

form in new ways. She has been<br />

quoted to say "My work deals with<br />

problems that are pre-gender,"<br />

she wrote. "For example,<br />

jealousy is not male or female."<br />

With the rise of feminism,<br />

her work found a wider audience.<br />

Despite this assertion, in 1976<br />

Femme Maison was featured on<br />

the cover of Lucy Lippard's book<br />

From the Center: Feminist Essays<br />

on Women's <strong>Art</strong> and became an<br />

icon of the feminist art movement.<br />

Later life<br />

In 1973, Bourgeois started<br />

teaching at the Pratt Institute,<br />

Cooper Union, Brooklyn College<br />

and the New York Studio School<br />

of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture.<br />

From 1974 until 1977, Bourgeois<br />

worked at the School of<br />

Visual <strong>Art</strong>s in New York where she<br />

taught printmaking and<br />

sculpture.She also taught for many<br />

years in the public<br />

schools in Great Neck, Long Island.<br />

In the early 1970s, Bourgeois would<br />

hold gatherings called "Sunday,<br />

bloody Sundays" at her home in<br />

Chelsea. These salons would be<br />

filled with young artists and<br />

students whose work would be<br />

critiqued by Bourgeois. Bourgeois<br />

ruthlessness in critique and her dry<br />

sense of humor lead to the naming<br />

of these meetings. Bourgeois<br />

inspired many young students to<br />

make art that was feminist in<br />

nature.However, Louise's long-time<br />

friend and assistant, Jerry Gorovoy,<br />

has stated that Louise considered<br />

her own work "pre-gender".<br />

Bourgeois aligned herself with<br />

activists and became a member of<br />

the Fight Censorship Group, a<br />

feminist anti-censorship collective<br />

founded by fellow artist Anita<br />

Steckel. In the 1970s, the group<br />

defended the use of sexual imagery<br />

in artwork.Steckel argued, "If the<br />

erect penis is not wholesome<br />

enough to go into museums, it<br />

should not be considered<br />

wholesome enough to go into<br />

women."

In 1978 Bourgeois was<br />

commissioned by the General<br />

Services Administration to create<br />

Facets of the Sun, her first public<br />

sculpture.The work was installed<br />

outside of a federal building in<br />

Manchester, New Hampshire.<br />

Bourgeois received her first<br />

retrospective in 1982, by the<br />

Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong> in New<br />

York City. Until then, she had been<br />

a peripheral figure in art whose<br />

work was more admired than<br />

acclaimed. In an interview with<br />

<strong>Art</strong>forum, timed to coincide with<br />

the opening of her retrospective,<br />

she revealed that the imagery in<br />

her sculptures was wholly<br />

autobiographical. She shared with<br />

the world that she obsessively<br />

relived through her art the trauma<br />

of discovering, as a child, that her<br />

English governess was also her<br />

father's mistress.<br />

Bourgeois had another<br />

retrospective in 1989 at<br />

Documenta 9 in Kassel,<br />

Germany.In 1993, when the Royal<br />

Academy of <strong>Art</strong>s staged its<br />

comprehensive survey of<br />

American art in the 20th century,<br />

the organizers did not consider<br />

Bourgeois's work of significant<br />

importance to include in the<br />

survey.However, this survey was<br />

criticized for many omissions, with<br />

one critic writing that "whole<br />

sections of the best American art<br />

have been wiped out" and pointing<br />

out that very few women were<br />

included. In 2000 her works were<br />

selected to be shown at the<br />

opening of the Tate Modern in<br />

London.In 2001, she showed at the<br />

Hermitage Museum.<br />

In 2010, in the last year of her life,<br />

Bourgeois used her art to speak up<br />

for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and<br />

Transgender (LGBT) equality. She<br />

created the piece I Do, depicting<br />

two flowers growing from one<br />

stem, to benefit the nonprofit<br />

organization Freedom to Marry.<br />

Bourgeois has said "Everyone<br />

should have the right to marry. To<br />

make a commitment to love<br />

someone forever is a beautiful<br />

thing."Bourgeois had a history of<br />

activism on behalf of LGBT equality,<br />

having created artwork for the AIDS<br />

activist organization ACT UP in<br />

1993.

Death<br />

Bourgeois died of heart failure on<br />

31 May 2010, at the Beth Israel<br />

Medical Center in<br />

Manhattan.Wendy Williams, the<br />

managing director of the Louise<br />

Bourgeois Studio, announced her<br />

death. She had continued to create<br />

artwork until her death, her last<br />

pieces being finished the week<br />

before.<br />

Bourgeois explores the relationship<br />

of a woman and the home. In the<br />

works, women's heads have been<br />

replaced with houses, isolating<br />

their bodies from the outside world<br />

and keeping their minds domestic.<br />

This theme goes along with the<br />

dehumanization of modern art.<br />

The New York Times said that her<br />

work "shared a set of repeated<br />

themes, centered on the human<br />

body and its need for nurture and<br />

protection in a frightening world."<br />

Her husband, Robert Goldwater,<br />

died in 1973. She was survived by<br />

two sons,<br />

Alain Bourgeois and Jean-Louis<br />

Bourgeois. Her first son, Michel,<br />

died in 1990.<br />

Work<br />

See also: List of artworks by Louise<br />

Bourgeois<br />

Femme Maison<br />

Main article: Femme Maison<br />

Femme Maison (1946–47) is a<br />

series of paintings in which<br />

Destruction of the Father<br />

Destruction of the Father (1974) is<br />

a biographical and a psychological<br />

exploration of the power<br />

dominance of father and his<br />

offspring. The piece is a flesh-toned<br />

installation in a soft and womb-like<br />

room. Made of plaster, latex, wood,<br />

fabric, and red light, Destruction of<br />

the Father was the first piece in<br />

which she used soft materials on a<br />

large scale. Upon entering the<br />

installation, the viewer stands in<br />

the aftermath of a crime. Set in a<br />

stylized dining room (with the dual<br />

impact of a bedroom), the abstract<br />

blob-like children of an overbearing<br />

father have rebelled, murdered,<br />

and eaten him.

telling the captive audience how<br />

great he is, all the wonderful<br />

things he did, all the bad people<br />

he put down today. But this goes<br />

on day after day. There is tragedy<br />

in the air. Once too often he has<br />

said his piece. He is unbearably<br />

dominating although probably he<br />

does not realize it himself.<br />

A kind of resentment grows and<br />

one day my brother and I decided,<br />

'the time has come!' We grabbed<br />

him, laid him on the table and<br />

with our knives dissected him. We<br />

took him apart and dismembered<br />

him, we cut off his penis. And he<br />

became food. We ate him up he<br />

was liquidated the same way he<br />

liquidated the children<br />

Exorcism in <strong>Art</strong><br />

In 1982, The Museum of Modern<br />

<strong>Art</strong> in New York City featured<br />

unknown artist,<br />

Louise Bourgeois's work. She was<br />

70 years old and a mixed media<br />

artist who worked on paper, with<br />

metal, marble and animal skeletal<br />

bones. Childhood family traumas<br />

"bred an exorcism in art" and she<br />

desperately attempted to purge<br />

her unrest with her work.<br />

She felt she could get in touch with<br />

issues of<br />

female identity, the body,<br />

the fractured family, long before<br />

the art world and society<br />

considered them expressed<br />

subjects in art. This was<br />

Bourgeous's way to find her center<br />

and stabilize her emotional unrest.<br />

The New York Times said at the<br />

time that "her work is charged with<br />

tenderness and violence,<br />

acceptance and defiance,<br />

ambivalence and conviction."<br />

Cells<br />

While in her eighties, Bourgeois<br />

produced two series of enclosed<br />

installation works she referred to as<br />

Cells. Many are small enclosures<br />

into which the viewer is prompted<br />

to peer inward at arrangements of<br />

symbolic objects; others are small<br />

rooms into which the viewer is<br />

invited to enter. In the cell pieces,<br />

Bourgeois uses earlier sculptural<br />

forms, found objects as well as<br />

personal items that carried strong<br />

personal emotional charge for the<br />

artist.

The cells enclose psychological<br />

and intellectual states, primarily<br />

feelings of fear and pain.<br />

Bourgeois stated that the Cells<br />

represent "different types of pain;<br />

physical, emotional and<br />

psychological, mental and<br />

intellectual ... Each<br />

Cell deals with a fear. Fear is pain ...<br />

Each Cell deals with the pleasure<br />

of the voyeur, the thrill of looking<br />

and being looked at."<br />

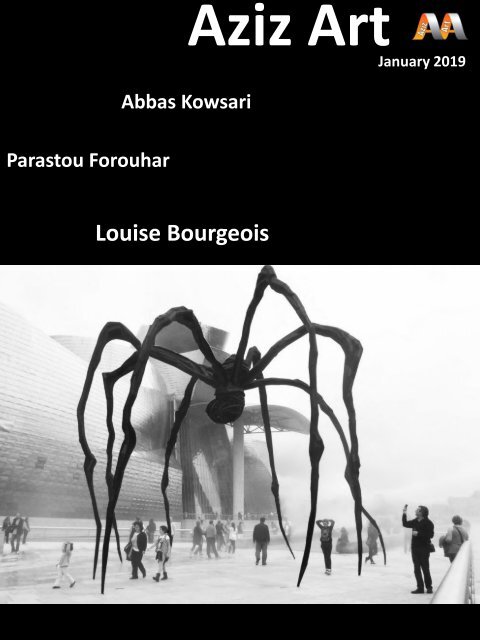

Maman<br />

Main article: Maman (sculpture)<br />

In the late 1990s, Bourgeois began<br />

using the spider as a central image<br />

in her art. Maman, which stands<br />

more than nine metres high, is a<br />

steel and marble sculpture from<br />

which an edition of six bronzes<br />

were subsequently cast. It first<br />

made an appearance as part of<br />

Bourgeois's commission for The<br />

Unilever Series for Tate Modern's<br />

Turbine Hall in 2000, and recently,<br />

the sculpture was installed at the<br />

Qatar National Convention Centre<br />

in Doha, Qatar.[35] Her largest<br />

spider sculpture titled Maman<br />

stands at over 30 feet (9.1 m) and<br />

has been installed in numerous<br />

locations around the world.It is<br />

the largest Spider sculpture ever<br />

made by Bourgeois. Moreover,<br />

Maman<br />

alludes to the strength of her<br />

mother, with metaphors of<br />

spinning, weaving, nurture and<br />

protection. The prevalence of the<br />

spider motif in her work has given<br />

rise to her nickname as<br />

Spiderwoman.<br />

The Spider is an ode to my mother.<br />

She was my best friend. Like a<br />

spider, my mother was a weaver.<br />

My family was in the business of<br />

tapestry restoration, and my<br />

mother was in charge of the<br />

workshop. Like spiders, my mother<br />

was very clever. Spiders are friendly<br />

presences that eat mosquitoes. We<br />

know that mosquitoes spread<br />

diseases and are therefore<br />

unwanted. So, spiders are helpful<br />

and protective, just like my mother.<br />

Maisons fragiles / Empty Houses<br />

Bourgeois's Maisons fragiles /<br />

Empty Houses sculptures are<br />

parallel, high metallic structures<br />

supporting a simple tray. One must<br />

see them in person to feel their<br />

impact. They are not threatening or<br />

protecting, but bring out the<br />

depths of anxiety within you.

Bachelard's findings from<br />

psychologists' tests show that an<br />

anxious child will draw a tall<br />

narrow house with no base.<br />

Bourgeois had a rocky/traumatic<br />

childhood and this could support<br />

the reason behind why these<br />

pieces were constructed.<br />

Printmaking<br />

Bourgeois's printmaking<br />

flourished during the early and<br />

late phases of her career: in the<br />

1930s and 1940s, when she first<br />

came to New York from Paris, and<br />

then again starting in the 1980s,<br />

when her work began to receive<br />

wide recognition. Early on, she<br />

made prints at home on a small<br />

press, or at the renowned<br />

workshop Atelier 17. That period<br />

was followed by a long hiatus, as<br />

Bourgeois turned her attention<br />

fully to sculpture. It was not until<br />

she was in her seventies that she<br />

began to make prints again,<br />

encouraged first by print<br />

publishers. She set up her old<br />

press, and added a second, while<br />

also working closely with printers<br />

who came to her house to<br />

collaborate. A very active phase of<br />

printmaking followed, lasting until<br />

the artist's death. Over the course<br />

of her life, Bourgeois created<br />

approximately 1,500 printed<br />

compositions.<br />

In 1990, Bourgeois decided to<br />

donate the complete archive of her<br />

printed work to The Museum of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong>. In 2013, The Museum<br />

launched the online catalogue<br />

raisonné, "Louise Bourgeois: The<br />

Complete Prints & Books." The site<br />

focuses on the artist's creative<br />

process and places Bourgeois's<br />

prints and illustrated books within<br />

the context of her overall<br />

production by including related<br />

works in other mediums that deal<br />

with the same themes and imagery.<br />

Pervasive themes<br />

One theme of Bourgeois's work is<br />

that of childhood trauma and<br />

hidden emotion. After Louise's<br />

mother became sick with influenza<br />

Louise's father began having affairs<br />

with other women, most notably<br />

with Sadie, Louise's English tutor.<br />

Louise was extremely watchful and<br />

aware of the situation. This was the<br />

beginning of the artist's<br />

engagement with double standards<br />

related to gender and sexuality,<br />

which was expressed in much of<br />

her work. She recalls her father<br />

saying

"I love you" repeatedly to her<br />

mother, despite infidelity.<br />

"He was the wolf, and she was the<br />

rational hare, forgiving and<br />

accepting him as he was.<br />

"Her 1993 work "Cell: You Better<br />

Grow Up", part of her "Cell"<br />

series, speaks directly to Louise's<br />

childhood trauma and the<br />

insecurity that surrounded her.<br />

2002's "Give or Take" is defined by<br />

hidden emotion, representing the<br />

intense dilemma that people face<br />

throughout their lives as they<br />

attempt to balance the actions of<br />

giving and taking. This dilemma is<br />

not only represented by the shape<br />

of the sculpture, but also the<br />

heaviness of the material this<br />

piece is made of.<br />

Architecture and memory are<br />

important components of<br />

Bourgeois's work. In numerous<br />

interviews, Louise describes<br />

architecture as a visual expression<br />

of memory, or memory as a type<br />

of architecture. The memory<br />

which is featured in much of her<br />

work is an invented memory -<br />

about the death or exorcism of<br />

her father. The imagined memory is<br />

interwoven with her real memories<br />

including living across from a<br />

slaughterhouse and her father's<br />

affair. To Louise her father<br />

represented injury and war,<br />

aggrandizement of himself and<br />

belittlement of others and most<br />

importantly a man who<br />

represented betrayal. Her 1993<br />

work "Cell (Three White Marble<br />

Spheres)" speaks to fear and<br />

captivity. The mirrors within the<br />

present an altered and distorted<br />

reality.<br />

Sexuality is undoubtedly one of the<br />

most important themes in the work<br />

of Louise Bourgeois. The link<br />

between sexuality and fragility or<br />

insecurity is also powerful. It has<br />

been argued that this stems from<br />

her childhood memories and her<br />

father's affairs. 1952's "Spiral<br />

Woman" combines Louise's focus<br />

on female sexuality and torture.<br />

The flexing leg and arm muscles<br />

indicate that the Spiral Woman is<br />

still above though she is being<br />

suffocated and hung. 1995's "In<br />

and Out" uses cold metal materials<br />

to link sexuality with anger and<br />

perhaps even captivity.

The spiral in her work demonstrates the dangerous search for<br />

precarious equilibrium, accident-free permanent change, disarray,<br />

vertigo, whirlwind. There lies the simultaneously positive and negative,<br />

both future and past, breakup and return, hope and vanity, plan and<br />

memory.<br />

Louise Bourgeois's work is powered by confessions, self-portraits,<br />

memories, fantasies of a restless being who is seeking through her<br />

sculpture a peace and an order which were missing throughout her<br />

childhood.

Parastou Forouhar born 1962 in<br />

Tehran is an Iranian installation<br />

artist who lives and works out of<br />

Frankfurt, Germany. Forouhar’s<br />

art reflects her criticism of the<br />

Iranian government and often<br />

plays with the ideas of identity.<br />

Her artwork expresses a critical<br />

response towards the politics in<br />

Iran and Islamic Fundamentalism.<br />

The loss of her parents fuels<br />

Forouhar’s work and challenges<br />

viewers to take a stand on war<br />

crimes against innocent citizens.<br />

Forouhar's work has been<br />

exhibited around the world<br />

including Iran, Germany, Russia,<br />

Turkey, England, United States and<br />

more.<br />

Early life and education<br />

The daughter of political activist<br />

Parvaneh Forouhar and politician<br />

Dariush Forouhar, Parastou was<br />

born in 1962 in Tehran, Iran. Her<br />

father critiqued the Iranian<br />

government and he founded and<br />

led the Hezb-e-Mellat-e Iran<br />

(Nation Party of Iran), which was<br />

a pan-Iranist opposition party in<br />

Iran.<br />

Her parents were stabbed in their<br />

home in the November of 1998,<br />

and Parastou relocated to Germany<br />

in 1991, where she has continued<br />

her work.She lives in exile because<br />

she is considered a political threat<br />

by the Iranian government.After<br />

her parents' death, Parastou<br />

channeled her grief into her art, her<br />

art explores topics from democracy<br />

to woman's rights to her parents'<br />

murder.Parastou studied <strong>Art</strong> at the<br />

University of Tehran from 1984<br />

until 1990, where she earned her<br />

B.A., she then continued to study at<br />

the Hochschule für Gestaltung in<br />

Offenbach am Main in Germany<br />

and went on to earn her M.A. in<br />

1994.Parastou lives with her two<br />

children in Frankfurt Germany now.<br />

Work<br />

Forouhar's work is autobiographical<br />

in nature and responds to the<br />

politics that have shaped and<br />

defined contemporary Iranian<br />

citizenship both in Iran and<br />

abroad.She works within a range of<br />

media including site specific<br />

installation, animation, digital<br />

drawing, photography, signs and<br />

products. Through her work<br />

16

she processes very real<br />

experiences of loss, pain, and<br />

state-sanctioned violence through<br />

animations, wallpapers, flipbooks,<br />

and drawings.Forouhar uses<br />

culturally specific motifs found<br />

within traditional Iranian arts such<br />

as Islamic calligraphy and Persian<br />

miniature painting to question<br />

the ways these forms can<br />

generate a lack of individual<br />

agency while adhering to a<br />

standardized understanding of<br />

beauty and cultural identity<br />

Forouhar's work is a<br />

utobiographical in nature and<br />

responds to the politics that have<br />

shaped and defined contemporary<br />

Iranian citizenship both in Iran<br />

and abroad. She works within a<br />

range<br />

of media including site specific<br />

installation, animation, digital<br />

drawing, photography, signs and<br />

products. Through her work, she<br />

processes very real experiences of<br />

loss, pain, and state-sanctioned<br />

violence through animations,<br />

wallpapers, flipbooks, and<br />

drawings. Forouhar uses<br />

culturally specific motifs found<br />

within traditional Iranian arts such<br />

as Islamic calligraphy and Persian<br />

miniature painting to question the<br />

ways these forms can generate a<br />

lack of individual agency while<br />

adhering to a standardized<br />

understanding of beauty and<br />

cultural identity.<br />

In 2012 she received the Sophie<br />

von La Roche Award in recognition<br />

for her work that confronts issues<br />

concerning displacement, gender<br />

and cultural identity.<br />

Solo exhibitions of Forouhar's work<br />

have been held at Stavanger<br />

Cultural Center, Norway; Golestan<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Gallery, Tehran; Hamburger<br />

Bahnhof - Museum fur Gegenwart,<br />

Berlin; City Museum, Crailsheim,<br />

Germany; and German Cathedral,<br />

Berlin.She has participated in group<br />

exhibitions at Schim Kunsthalle,<br />

Frankfurt; Frauenmuseum Bonn;<br />

Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong>, Frankfurt;<br />

Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum,<br />

Joanneum, Graz,<br />

Austria; House of World Cultures,<br />

Berlin; Deutsches Hygiene-<br />

Museum, Dresden; Jewish Museum<br />

of Australia, Melbourne; and Jewish<br />

Museum San Francisco.

Her work can be found in the<br />

following permanent collections:<br />

The Queensland <strong>Art</strong> Museum,<br />

Queensland; Belvedere, Vienna;<br />

Badisches Landesmuseum,<br />

Karlsruhe; Museum of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong>, Frankfurt; and the<br />

Deutsche Bank <strong>Art</strong> Collection.<br />

In 2002, the Iranian Cultural<br />

Ministry censored Forouhar's<br />

photo exhibition, Blind Spot, a<br />

collection of images depicting a<br />

veiled, gender-neutral figure<br />

with a bulbous, featureless face.<br />

Forouhar chose to exhibit the<br />

empty frames on the wall on<br />

opening night instead of forgoing<br />

the show.<br />

Forouhar and her brother got<br />

involved in activism after their<br />

parents got brutally murdered and<br />

they weren't allowed to publicly<br />

mourn or speak out about their<br />

deaths. Her artwork critiques the<br />

Iranian government and focuses on<br />

examining her identity and culture.<br />

Forouhar has been featured in<br />

several art fairs including the<br />

Brodsky Center Fair, at Rutgers<br />

University in 2015, and Pi <strong>Art</strong>works<br />

fair Istanbul/London, in 2016 and<br />

2017 (she was at both locations: in<br />

Contemporary Istanbul and<br />

London)

Abbas Kowsari was born in 1970, in Iran. He graduated in 1988 with a<br />

diploma from Shariati High School in Tehran, where he continues to live<br />

and work.<br />

Kowsari has worked for over ten leading Iranian newspapers, most of<br />

them now banned from publishing. He currently works as the senior<br />

photo editor for E’temad newspaper in Tehran.<br />

His photos have been published in Paris Match, Der Spiegel and Colors<br />

magazine of Benetton, along with several other international<br />

publications.<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

2006-present Photo Editor E’temad Newspaper<br />

2007-present Photo Editor Sarmayeh Economics Newspaper<br />

2003-present Photo Editor Haft Monthly <strong>Art</strong>s Magazine –Closed Down<br />

Exhibitions<br />

2008 Shade of Water – Shade of Earth, Aaran <strong>Art</strong> Gallery Tehran<br />

2004 Muslims Muslims, La Vilette Paris<br />

2003 Portraits, French Embassy Damascus<br />

2002 Iran Contemporary Photographers, Assar <strong>Art</strong> Gallery Tehran<br />

21

http://www.aziz-anzabi.com