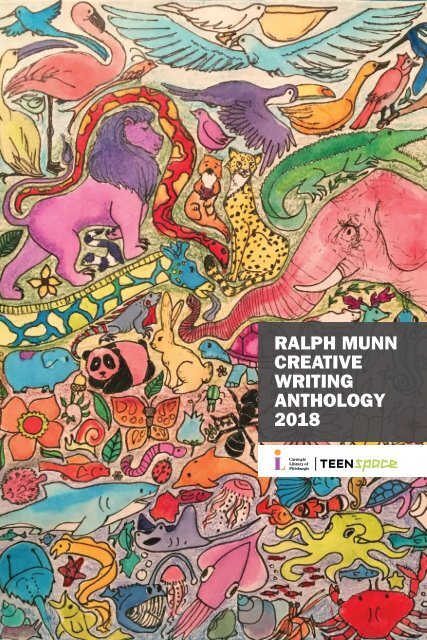

2018 Ralph Munn Creative Writing Anthology

The annual Ralph Munn Creative Writing Anthology is a book of creative writing by teens distributed to all Allegheny County public and school libraries.

The annual Ralph Munn Creative Writing Anthology is a book of creative writing by teens distributed to all Allegheny County public and school libraries.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

RALPH MUNN<br />

CREATIVE<br />

WRITING<br />

ANTHOLOGY<br />

<strong>2018</strong>

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong><br />

<strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong><br />

<strong>Anthology</strong><br />

<strong>2018</strong>

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong><br />

<strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong><br />

<strong>Anthology</strong><br />

<strong>2018</strong><br />

Committee Chair<br />

Sienna Cittadino, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh–Allegheny<br />

Committee Co-Chair<br />

Michael Balkenhol, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh–Squirrel Hill<br />

Editorial Committee<br />

Emily Fear, Sewickley Public Library<br />

James Graham, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh–Hazelwood<br />

Katelyn Cove, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh–Beechview<br />

Marian Streiff, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh–Mt. Washington<br />

Matt Zeoli, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh–Brookline<br />

Book Design and Copyediting<br />

Connie Amoroso<br />

Cover Illustration<br />

Lexi Hall

Copyright © <strong>2018</strong> by Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.<br />

All rights revert to the individual authors.<br />

Printed and bound in the United States of America.<br />

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents<br />

About the <strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> Contest 8<br />

The Judges 9<br />

Short Prose<br />

(First Place)<br />

Brianna Kline-Costa Bruised Girls Are Like Rabbits 13<br />

(Second Place)<br />

Ciara Sing<br />

A Pop Quiz to Make Myself Even<br />

More Confused About Identity 17<br />

Aliza Hamid A Series of Unfortunate Subway Events 20<br />

Amanda Lu You are me. I am you. 26<br />

Brianna Longo The Outcasts 34<br />

Cari Molin Pikachu Buddy 44<br />

Chelsianna Havko A Good Day to Die 46<br />

Destiny Perkins Lineage 51<br />

Evie Jin The Keeper 53<br />

Evie Jin After the Show 60<br />

Jacqueline LeKachman The Voicemail 68<br />

Julian Riccobon Baby Steps 75<br />

Julian Riccobon Tigers and Elephants 85<br />

Lemlem Gamble Self 96<br />

Madeline Bain Healing 98<br />

Madison Jones The Brave Boy 102<br />

Nisha Rao Growing Up Feminist 104<br />

Noor El-Dehaibi Matt 107<br />

Qingqing Zhao Breakfast with Strangers 110<br />

Serena Zets Frida 118<br />

Tess Buchanan Mother Earth: A Bird’s End 120<br />

Will Thayer<br />

The End of the World Circus<br />

Is Going Great! 122

Poetry<br />

(First Place)<br />

Marissa Randall Future’s Spark 127<br />

(Second Place)<br />

Ilan Magnani The Extinction of a Body 129<br />

Aaliyah Thomas Coffin Birth 130<br />

Alex Flagg A Familial Disconnect 132<br />

Amanda Wolf Three’s Company 133<br />

Amanda Wolf Skaters 135<br />

Brianna Caridi the Blood moon is no less Beautiful 137<br />

Chelsianna Havko Failure 138<br />

Chloe Butcher Alien 139<br />

Chloe Butcher Winter 140<br />

Chloe Walls Where I’m From 141<br />

Ciara Sing<br />

For the Black Boys That Never<br />

Learned How to Swim 142<br />

Emily Rhodes Carrion 143<br />

Erin Park The Worker’s Word 144<br />

Hazel Rouse Sirens 146<br />

Hunter Greenberg Legs 148<br />

Jack Scott The Winter Sport: A Ski Racing Sonnet 150<br />

Jordan Crivella operation protect the people 151<br />

Kieren Konig Water 153<br />

Lauryn David Parental Guidance 155<br />

Lexi Hall Like a Used Car 157<br />

Lianna Rishel Case, Severity B 158<br />

Lily Tolchin Meteor Shower 159<br />

Maddie Figas<br />

Amelia Bedelia and I Walk Through<br />

the Aisles of Tsunami Surf Shop 160<br />

Maddie Figas<br />

Corey I’m <strong>Writing</strong> Because Nothing<br />

Good Has Happened Since You Died 162<br />

MaKayla Wilson Homewood 164

Maria Kresen Rape of Youth 166<br />

Maya Shook The Little Guys 167<br />

Olivia Balogh Enough 169<br />

Serena Zets An ode to ollanta 171<br />

Tara Stenger Prized Fish 173<br />

Thalia King Malala and I Tour America 175<br />

Acknowledgments 177

About the <strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong><br />

<strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> Contest<br />

Born in 1894, <strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> started his library career as a reference librarian in<br />

Seattle in 1921, became Flint Public Library’s Librarian in 1926 and then on<br />

to the Directorship of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in 1928 until 1964.<br />

During that time, he held the positions of Director and Dean of the library<br />

school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University,<br />

until it became part of the University of Pittsburgh in 1962. An endowment<br />

fund created to honor his legacy now provides support for creative writing<br />

opportunities for young adults through the Library.<br />

Thanks to research by Sheila Jackson and the Development Office, we know<br />

that the original use of this endowment, contributed by friends of <strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong>,<br />

began in the 1960s for a lecture series on librarianship and transitioned to use<br />

for creative writing workshops in the 1970s, under supervision of the Carnegie<br />

Institute, which oversaw the fund. After a hiatus in the 1990s the contest was<br />

revived in 2007 with additional help from other bequests. Library staff and<br />

volunteers led workshops and formed an editorial board to judge entries to the<br />

contest and find professional writers to choose contest winners. In the first year,<br />

the contest took off, receiving nearly 300 entries, and it has not stopped being<br />

a popular and anticipated part of Teen Services.<br />

Since the creative writing contest joined forces with the Labsy awards under<br />

the Teen Media Awards banner, it continues to evolve as a way for Allegheny<br />

county teens to be acknowledged, published, and awarded for their work and<br />

creativity. The libraries in the county are proud to support this creative work<br />

and provide spaces, mentors, and resources toward that end.<br />

Tessa Barber<br />

Chair, <strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> Committee (2015 – 2016)<br />

8

The Judges<br />

Poetry<br />

Sharon Flake<br />

Sharon G. Flake has an international reputation as a top children’s and YA<br />

author. Her breakout novel The Skin I’m In, established her as a must read<br />

author among middle and high students, parents and educators. She has spoken<br />

to more than two-hundred thousand young people, and hugged nearly as many.<br />

Flake has penned nine novels, numerous short stories, plays, and a picture<br />

book entitled, You Are Not a Cat. Her work has been translated into multiple<br />

languages including French, Korean and Portuguese. She has been awarded<br />

several Coretta Scott King Honor awards along with the YWCA Racial Justice<br />

Award, and her work has appeared on many prestigious lists including the<br />

Kirkus Review’s Top Ten Books of the Year; Best Books for Young Adult Readers<br />

by the American Library Association; Top Ten Books for the Teen Age by<br />

the New York Public Library; Top Twenty Recommended Books to Read by<br />

the Texas Library Association, the Junior Library Guide Selection; 100 Books<br />

Every Teenage Girl Should Read; Booklist’s Editor’s Choice Award, and others.<br />

Prose<br />

Abeer Hoque<br />

Abeer Y. Hoque is a Nigerian born Bangladeshi American writer and photographer.<br />

Her books include a travel photography monograph, The Long Way<br />

Home (2013), a linked story collection, The Lovers and the Leavers (2015), and<br />

a memoir, Olive Witch (2017). She has won fellowships from Fulbright, NEA,<br />

and NYFA, and her work has been published in Guernica, The Rumpus, Elle,<br />

Catapult, ZYZZYVA, and the Commonwealth Short Story Competition, among<br />

others. She has B.S. and M.A. degrees from the Wharton School, an M.F.A.<br />

from the University of San Francisco, and she has held two solo photography<br />

exhibitions. See more at olivewitch.com.<br />

9

Short Prose<br />

First Place<br />

“Bruised Girls Are Like Rabbits”<br />

by Brianna Kline-Costa<br />

Second Place<br />

“A Pop Quiz to Make Myself Even<br />

More Confused About Identity”<br />

by Ciara Sing

Brianna Kline-Costa<br />

Grade 11<br />

Pittsburgh <strong>Creative</strong> and Performing Arts 6–12<br />

Short Prose<br />

Bruised Girls Are Like Rabbits<br />

(Non-Fiction)<br />

“Mexican, huh?” He leans against the wall to stabilize himself. He reeks of<br />

liquor. “Well, hola.” He laughs, his body swaying and feet stumbling across<br />

the title floor.<br />

I am pressed into the corner of the kitchen, my fingers tracing the edge<br />

of counter. The door to the back porch swings open, gusts of winds sending<br />

it careening into the wooden railing with a heavy thud. As night fell, the<br />

temperature of the kitchen dropped to a disconcerting chill, and I use my hands<br />

to mask my goosebumps, and the way my veins burn through my skin under<br />

florescent lights. He stands leaning against the kitchen wall across from me. I<br />

stare at the rusted stove burners, blushed with heat.<br />

“Dad, stop.” My friend turns towards me, rolling her eyes and smiling. Her<br />

face is apologetic. Like we are sharing a joke. I smile back at her, but I know<br />

my face is tight and pale, and my smile is forced and unconvincing. She doesn’t<br />

notice though. She looks through me.<br />

“No, no, see, here’s the thing. . . .” His body falls into the chair behind<br />

him. “I don’t mind them in the country, as long as they know their role. That’s<br />

the important part.”<br />

He leans towards us, and I can feel his hot breath on my face. My cheeks<br />

flush in anger and embarrassment. I feel my back pressed until the wall. My<br />

eyelashes tremble, and I worry that he can see the gentle tremors of my body,<br />

like a rabbit pressed against the age of its cage, the rapid beating of its heart<br />

echoing in the silence like a snare drum. He drunkenly turns his bottle upside<br />

down, and laughs as beer sloshed against my feet, seeping into my socks and<br />

yellowing the white. The stale smell of cheap beer. His teeth yellowed and his<br />

face contorted uglily.<br />

“Why don’t you get on your knees and clean my floor, sweetheart?”<br />

I was thirteen. It was the age when I stopped wanting to be looked at, when<br />

13

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

I started straightening my hair every day, so familiar with the sizzle of anti-frizz<br />

products as I clamped down, the air thick with the smell of burnt hair; when<br />

I started wearing cheap drugstore mascara that smudged and left dark bruises<br />

under my eyes, and black specks across my lids. Started becoming conscious<br />

of how I smile (never with my teeth, until the braces were off), what angle I<br />

stood (pivoted slightly to the right to counter the appearance of hip dips), how<br />

I laughed (head back, hand over my mouth to cover my lips).<br />

That night, we set up blankets on her couch and watch horror movies.<br />

Her house smells of cigarette smoke, and is littered with crushed beer bottles,<br />

and the smell of weed reeks from her older brother’s room, but that was most<br />

of our homes. Things didn’t bother us as much; men would yell things out of<br />

the window of their car to us when we walked to the convenience store, and<br />

we would flip them off or yell things back and run away giggling when they<br />

turned the car back around. When men followed us from our bus stops, we<br />

would complain to our friends about it, rolling our eyes like the attention of<br />

boys and men was the most inconvenient thing in our lives, searching out of<br />

our peripheral for any tinge of jealousy in their eyes, but deeper than that, it<br />

scared us and it left us uncomfortable in our bodies. We knew that walking<br />

down certain streets, our bodies didn’t belong to us anymore, and we were told<br />

that we liked this, even by each other.<br />

I hear him when he stumbles through the door. The keys jangling in the<br />

lock, the door knob twisting, turned by clumsy fingers. From the living room,<br />

we can hear him wiping off his shoes on the mat and opening the fridge for<br />

another beer. His vision getting a little more blurred and dizzy. His voice getting<br />

a little more slurred. Drinking by himself one room over, legs propped up on<br />

the table.<br />

I don’t say a single word throughout the whole encounter. After he speaks,<br />

he waits a moment to see if I’ll say anything in my defense. His face is a foot<br />

from mine, and I see how it flushes when he bends over, sweat dripping down<br />

his temples and plastering greyed curls to the sides of his head. I imagine how<br />

I look in the moment: eyes round and wide, face empty and bovine, my arms<br />

thin and freckled, legs veined and pale, incredibly breakable. Like translucent<br />

stained glass.<br />

He laughs at my empty and frightened silence, then saunters out of the<br />

kitchen. We hear the front door slam, and the engine of the truck rev, and pull<br />

away. It is eleven thirty. I lean against the table and try to cover my shaking.<br />

14

“Sorry about that.” She turns back towards me, her hair falling over her<br />

face, the same mousy brown as her father’s without the gray streaks, her eyes<br />

the same deep amber. “Wanna watch another movie?”<br />

Short Prose<br />

He knew that it would make me uncomfortable, and he knew that I would have<br />

nothing to say, and in that he got to exert an incredible power over me. A power<br />

more freeing and overwhelming that all the gin and vodka in his cupboards.<br />

One that I learned men couldn’t resist.<br />

I can’t think about what it means to be Hispanic without thinking about<br />

what it means to a girl. The two are too connected in my mind. That night<br />

had as much to do with sex as with race, and more than anything, with power.<br />

It’s a beautiful thing to be a woman, and that’s something I learned later, when<br />

I grew and saw all the millions of ways women could be beautiful. But’s it’s a<br />

terrible thing to be a woman, too, and that’s the first lesson I learned, and the<br />

one I can never seem to outrun.<br />

The power is in how we see ourselves. Growing up, I saw Latino women as<br />

maids, housekeepers, and if they weren’t the help, they were overtly sexualized.<br />

Thick lipped, wide hipped, cinnamon skin, long dark hair, with snippy remarks<br />

and little moral compass. These were the images on television. In my life, I<br />

had even less inspiration. I had spent my whole childhood after the age of six<br />

living in Pittsburgh, and I didn’t know a single Latino woman. The women, in<br />

a broader sense, in my life hadn’t felt any more empowered to me. Adolescent<br />

girls seemed to be living in a dark and empty abyss of insecurity and feigned<br />

happiness. Girls who wore low cut shirts with brightly colored pushup bras,<br />

their chests looking raw and almost juvenile. Who constantly pulled the collar<br />

up whenever they felt stares. Girls who spent time with boys who scared them.<br />

Girls who giggled uncomfortably at jokes at their own expense, because they<br />

were pushed into the corner of complying and seeming silly or easy, or being<br />

known as obnoxious and rude. Girls who had tried to apply cheap eyeshadow<br />

they lifted from the corner store, sloppy and creased. Hands constantly drifting<br />

to their eyes, letting hair fall over their face as if wishing they hadn’t worn it in<br />

the first place. Mustard yellows that accentuated the sallowness of their skin.<br />

Bright blues that accented the dark circles under their eyes. Like bruises.<br />

Now it’s two o’clock. A movie is playing, but I’m not sure which one. I am<br />

drifting in and out, the dialogue of the television suspended in my sleep. Thick<br />

and fragrant smoke from her brother’s room hangs in the damp air, making my<br />

head spin. My friend has fallen asleep, her head tilted to the side, a small line<br />

15

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

of drool down her chin. I wonder if she is afraid of him. Sometimes she flinches<br />

when she heard the door open. The only time a girl looks happy is when she<br />

is sleeping.<br />

I go to the kitchen to get a glass of water.<br />

The cabinet is filled with an assortment of cheap plastic cups, rough with<br />

scratches. The sink makes a soft clunking noise as the water runs. The bubbles<br />

set. I take a sip.<br />

As I walk back to the living room, I feel something cool seep into my sock.<br />

It’s the puddle of beer, which has seeped into the floor and left a deep, mahogany<br />

stain. I take off the wet and stained sock, wringing it in my hands slightly. I<br />

step over the puddle and into the living room.<br />

The volume on the TV is low and persistent. I can hear music playing from<br />

somewhere, likely her brother’s room upstairs. I see headlights flash in the<br />

windows, and my heart freezes for a moment, thinking that her dad is home,<br />

but I hear the car retreat into the dark of the street, and my heart beats slows.<br />

As I fold my body under a thinning, frayed blanket that smells of mildew and<br />

laundry detergent, I barely have to time to think before I am pulled into a<br />

restless sleep. Four or five hours of peace and dark. Four or five hours that I<br />

have to look happy.<br />

16

Ciara Sing<br />

Grade 12<br />

Pittsburgh <strong>Creative</strong> and Performing Arts 6–12<br />

Short Prose<br />

A Pop Quiz to Make Myself Even<br />

More Confused About Identity<br />

(Non-Fiction)<br />

True or False: In the South, there’s the “one drop rule,” meaning that a single<br />

drop of “black blood” makes a person black.<br />

True or False: When you look at the unbleached manila birth certificate,<br />

you can’t deny that the far-too-neat-signature-for-a-man splotched in black ink<br />

is your father, your flesh and blood.<br />

True or False: In court, cases have been known to use the “traceable amount<br />

rule” during Jim Crow segregation.<br />

True or False: During a Kwanzaa celebration, you found yourself amongst<br />

students that very well could be strangers but never felt safer. Tears brimmed in<br />

the corner of your eyes as you fingered the figurine decorated in straw.<br />

True or False: Umajaa is the idea of being centered with one’s self.<br />

True or False: In seventh grade, you were called “tragic mulatto” in an<br />

attempt for you to harm yourself.<br />

True or False: You consider yourself a tragic mulatto.<br />

True or False: You buy your hair products in the ebony aisle at Rite-Aid<br />

with your white mother.<br />

True or False: As your hand pulled the black button of the lighter, you<br />

thought you could see yourself in the orange flame melting the black wax on<br />

top of the wooden Kinara.<br />

17

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

True or False: Mental slavery is the state of mind where discerning between<br />

liberation and enslavement is twisted.<br />

True or False: You get dismissive when people begin to ask about your<br />

family dynamics. You try to fluff out your curls as if the kinkiness can hide your<br />

self-consciousness about excessive navel-gazing regarding your racial identity.<br />

True or False: During black history month, your mother used to dress you<br />

up as famous black pioneers.<br />

True or False: When you think of your mother you only think of coffee<br />

grinds in your hair, baking soda and late night cleaning.<br />

True or False: Your sister use to think you were adopted but you never once<br />

questioned her love for you.<br />

True or False: In the U.S., black and white interracial relationships only<br />

make up about 23%.<br />

True or False: You’ve never been able to get your haircut at a normal hair<br />

salon.<br />

True or False: Race is defined by the principle of “hypodescent,” in which<br />

anyone with any known African ancestry was defined by black. This one-drop<br />

motivates eugenic fears.<br />

True or False: When you’re sitting at the dining table and your father begins<br />

to talk about who you might take to your school dance, you freeze up. You know<br />

his unspoken question is what type of boy are you attracted to, even if you’re<br />

attracted to boys. You struggle with the answer. You grip your napkin against<br />

your flattened-out thigh. You take your time chewing the rice. You should<br />

answer correctly. He doesn’t want you to be attracted to white men because he<br />

doesn’t want his grandchildren to ever feel disconnected with their black heritage<br />

or him. You mutter you’re going with friends instead.<br />

True or False: You are both the oppressed and the oppressor.<br />

True or False: When you go to the barber on East Ohio Street with your<br />

18

dad, the one with cracked up concrete and a man posted on the corner, the<br />

non-regulars question if you’re his daughter. They call you pretty and eye you<br />

up when your dad gets turned around.<br />

Short Prose<br />

True or False: Racial healing occurs after a lifetime.<br />

19

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

Aliza Hamid<br />

Grade 12<br />

Gateway High School<br />

A Series of Unfortunate<br />

Subway Events<br />

(Non-Fiction)<br />

Before starting eleventh grade in the fall, I skipped gleefully under the afternoon<br />

June sun along the Old William Penn sidewalk towards Subway for my first job<br />

interview while grasping onto my unsophisticated resume pertaining to nothing<br />

about skills or past work experiences. The almost white paper expressed my<br />

personality traits such as how I was a happy, kind, people-person and could<br />

absorb new skills like a sponge; however, I soon learned the unfortunate outcomes<br />

of a first job. Getting a first job makes every teen believes that he or she<br />

will purchase a used car, buy new clothes, go out to dinner with friends, and<br />

take part in any fun activities, but just as the reality of a job hits every teenager<br />

like a car, I got hit hard by the reality bus instead and understood that I should<br />

not have to deal with events that make me unhappy.<br />

Sitting down in the air-conditioned fast-food chain at a sticky booth, I took<br />

in the aroma of fresh baked bread flying to me while staring at the bustling traffic<br />

outside of a window the size of a wall, which I would eventually want to run<br />

into after two years of working with horrific coworkers, abominable customers,<br />

and the god-awful work environment. To sit underneath the warm yellow lights<br />

allowed me to clearly see the face of a man with mainly gums in his mouth<br />

and four teeth spread apart almost as if a magnetic force did not want them to<br />

collide. Brian, the manager of the Subway, got up and shook my hand, and I<br />

started to discuss why I applied: “I need work experience and money for a car.”<br />

Laughing, Brian replied, “Do you want this job?”<br />

“Yes. It’s summer too, I can start today.”<br />

With his gap-toothed smile, he spit as he said, “It’s yours.”<br />

After one week of training with my co-worker Joe, his smoking addiction<br />

overcame his thought process, and he made me work alone for thirty minutes<br />

while he went on a smoke break, telling me that I will not find too many customers<br />

entering the store and that I should have an easy time working. Surprisingly,<br />

20

a large group of people entered the store, and I tried my best to speed across the<br />

line, making the food, ringing up customers, and bagging. After burning five<br />

sandwiches, dropping four on the floor, and crying in front of ten customers, I<br />

exhaustedly witnessed Joe wandering back to the store an hour later to ask me<br />

how working alone for an hour went.<br />

Sticking a pack of Marlboros in his pocket, he asked, “No customers came,<br />

right?”<br />

Wiping my tears away and picking up my fake smile, I slyly kicked a piece<br />

of charcoal burnt bread under the counter and responded to Joe’s question with<br />

a simple saying: “easy peasy lemon squeezy.”<br />

Eventually, Subway gained a new employee who I became friends with,<br />

Michael Holmes. Michael started to become my main coworker because we<br />

could work the same hours, so we met a diverse group of customers together.<br />

One day, while sitting in a state of fatigue under the burning fluorescent lights<br />

on the shiny metallic counter, Michael and I stared at each other in boredom,<br />

half-falling asleep. Soon we heard the ding! of the front door opening, and two<br />

giant men stomped in.<br />

“Finally, people,” Michael smiled as he said those words, but he would soon<br />

regret them.<br />

I could only let out a mundane sigh and walk to the front counter to start<br />

the sandwiches and exhibit no traits that would make customers want to have<br />

a conversation with me.<br />

Plainly I asked the basic question, “What kind of bread?”<br />

“Herbs and Cheese, you should smile more.”<br />

Ignoring the end remark, I asked the next question, “What kind of<br />

sandwich?”<br />

“Italian BMT, where are you from?”<br />

Another unwanted remark made me stare at the men with strict eyes and<br />

clenched teeth while I asked the next question, “What kind of cheese?”<br />

“Pepper jack and toasted. Hey, tall man!” They turned to Mike staring at<br />

me to see if I would yell at them, “Are you guys together?”<br />

“No, we aren’t.” I really wished Mike had lied, but I could see the fear in<br />

his lanky 190-pound body next to both of the 250-pound men triple his size.<br />

Thinking they had the right to flirt awfully with me, the one man started<br />

to talk more to me about how popular he was among ladies.<br />

“You won’t need this job if you come with me, I got a lot of girls working<br />

for me.” His creepy gold tooth gave off a urine color instead of shiny gold in<br />

the light.<br />

Trying to get rid of the two men, I responded, “Ummm no, have a nice day.”<br />

Short Prose<br />

21

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

Persistent, the bigger man with the gold chain kept ogling while his sidekick<br />

watched him speak. Because I felt disgusted by their talk, I walked to the<br />

back halfway through their sandwich and let Michael deal with them. Scared,<br />

Mike walked back and asked me to come back out front.<br />

Raising his arms in the air, he said, “They’ll kill me, Aliza.”<br />

“They aren’t even talking to you or about you! Why are you scared, dumb***,<br />

I’m not coming up front, you can deal with them.”<br />

He walked back front and let out the words, “Ugh, fine.”<br />

Still hollering, the men talked louder so I could hear what they said while<br />

I sat in the back peeking out from the corner to check on Michael.<br />

“She’s pretty, isn’t she?” said the sidekick in a creepy, grim manner.<br />

“Uh, yeah, I don’t know,” said Michael as he rang them up.<br />

The pimp protested against Michael, “We’ll stay until she comes back out.”<br />

“She won’t, have a nice day,” and with that, Michael ran back to me and<br />

exclaimed they wouldn’t leave.<br />

After waiting for ten extra minutes, the men laughed at Michael and said he<br />

looked nice then called him back up to the counter to ask for a piece of paper.<br />

“Give her this number, tell her to ask for Big Daddy.”<br />

Sitting in the back, I started laughing at that nickname. Michael handed<br />

me the paper, I turned to him, and we just laughed over how peculiar of a<br />

situation we handled.<br />

Not even looking at the number, I ripped the paper in half.<br />

Whispering, Michael said, “Shhh, Aliza! They’re still here by the back<br />

door.”<br />

“I don’t care, they can suck it.”<br />

Ding! The back door opened and the stomping disappeared.<br />

Over the course of half a year at Subway, I met more odd customers, made<br />

some regulars, and watched new employees that came and went. However, I<br />

was the only girl who worked there. Richard Sentimer, the nicest guy working<br />

at Subway, told me he made more money than me. Furious, I got the truth out<br />

of all the guys working at Subway one by one through throwing a tantrum and<br />

screaming at each one of their faces. Confronting my boss and new manager<br />

became the next step, but I found out our new manager, Allyse, and the owner,<br />

Greg, were a father-daughter duo. Constant reminders that I started before<br />

all the guys at Subway, worked the most hours, and did the most work on the<br />

checklist, did not get me a raise. Plan B meant I had to throw another tantrum.<br />

I showed up early to work while Allyse worked in her dingy square office<br />

with a hole in the wall after someone threw a hammer to it, and I asked her<br />

22

for a raise and explained that all the guys make more money than me for no<br />

reason. The guys did not even have past work experience to allow them to make<br />

more money.<br />

Allyse sighed and said “Aliza, I don’t decide who gets a raise and who<br />

doesn’t, Greg does.”<br />

Rage built inside me because I knew she lied straight to my face, and I let<br />

it all out. “Richard, Mike, Nick, and Phil all told me that you gave them a raise,<br />

they showed me their paychecks, they all started working way after I started, and<br />

I’m the one making minimum wage? All of them, except for Richard, don’t do<br />

**** at their job and sit here watching TV, playing on their phones, and harass<br />

me while I’m the one doing everything, and I have to constantly yell at them to<br />

do work, and I don’t get a raise? What do I need to ****ing do, Alysse? Huh?<br />

Grow a penis? You don’t give a crap cause your dad owns like twenty-seven<br />

subways and you don’t need the money, but I’m tired of the guys making jokes<br />

that I get paid less and I want a raise now.”<br />

I wished a fly would fly into her mouth as she stared at me with her mouth<br />

open and her eyes wide, in shock, and most likely a little fear, she finally said,<br />

“Yeah, your next paycheck will have a raise, I’m gonna go, bye.”<br />

Standing a little taller, I texted the guys and gave them a piece of my mind,<br />

and then I opened my paycheck two days later and smiled as I noticed that it<br />

had increased.<br />

Even though I started making more money, the work environment made me<br />

more uncomfortable than getting sand inside clothes at the beach. Around the<br />

holidays, drunks and drug users started stumbling into Subway, and working<br />

alone at night caused me to keep a look out instead of falling asleep at work.<br />

New Years’ night, I worked the closing shift, and a very drunk couple walked<br />

in, grabbing onto each other to keep standing. The stench of alcohol filled<br />

my nose as the drunk woman blurted out her order, “I just want a salad with<br />

cucumbers and chicken!”<br />

“Any other veggies? Lettuce or spinach?” I thought she may want other<br />

veggies, hence the purpose of a salad.<br />

“Nope, just chicken and cucumbers.”<br />

I started on the next customer and turned to the drunk couple and muttered,<br />

“Alright, here you go. Have a nice evening.” In the middle of talking to<br />

a regular customer, I heard the loud metal door of the drunk couple’s truck<br />

slam and the angry tomato-red man screaming about the salad, “What the hell<br />

is this?!”<br />

Nonchalantly I said, “A salad.”<br />

Short Prose<br />

23

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

“What the hell is this? This isn’t a ****ing salad, it’s just cucumbers and<br />

chicken.”<br />

Starting to become sassy, I responded, “According to your girlfriend, that’s<br />

a salad.”<br />

He grumbled, “I want a refund.”<br />

“I can’t do that, I’m not the manager.” Losing my patience, I also exclaimed<br />

“I’m going to call the police if you don’t chill, man.”<br />

“Chill? Really? Make me a new ****ing salad.”<br />

“Ok, what do you want in it? Lettuce, spinach, tomatoes, what?”<br />

“A ****ing salad.”<br />

I think he and his girlfriend were Subway virgins and did not understand<br />

the concept that they needed to tell me what goes in their food. I gave him the<br />

choices of the vegetables, but disappointingly, his last two brain cells could not<br />

create a synapse. Infuriated, I took a bowl and threw veggies in it, talking to<br />

the man sweeter than candy to purposely get on his nerves and make him feel<br />

like an imbecile. After finishing the salad for the ignoramus, in my most cheery<br />

cartoon voice, I smiled and screamed at the man’s face, “Have a nice night!” I<br />

showed all 32 of my teeth and waved at him like a stranger waving bye-bye to a<br />

baby in a grocery store. Cowardly, the salad man turned around and mumbled<br />

the single word his peanut-sized brain could create: “Night.”<br />

By the second year of my afterschool Subway job, Subway started to go<br />

under. Not everyday does an employee get to see drug deals on the roof of the<br />

building they work at, in the men’s bathroom, behind the dumpster, and at a<br />

“gardening store” used as a front. As a closer, I had the grand activity of throwing<br />

the garbage away every single night. Garbage bins sat all the way across the<br />

back parking lot right on the edge of the woods, probably 40 feet away from my<br />

car, that meant I run back and forth three to four times every night carrying<br />

multiple boxes and bags, giving a murderer three to four chances to sprint at<br />

me. After running away from various drug deals, random cars by the edge of<br />

the woods, and a Fox’s Pizza employee who thought that following me to the<br />

dumpster to scare me would be a fun prank, I became too frightened to close<br />

alone. Explaining the incidents to Alysse started to make me tiresome because<br />

she did not believe me. However, I got the rest of the guys to close one night<br />

and see what occurred, they also notified Alysse of the delinquency. Michael<br />

and I sat outside one May afternoon playing frisbee and because I got bored after<br />

five minutes I noticed the “gardening” shop left their back door open. Having<br />

no fear, I told Michael that I will sneak into the store through the back to see<br />

what “plants” they sold because we found it bizarre how teenagers and college<br />

24

students kept going to the “gardening” shop, when in reality, teens do not even<br />

give a crap about gardening.<br />

Hoping off the trunk of my car I turned to Michael, “Let’s do some<br />

sleuthing”<br />

Standing on my car, Michael laughed and warned me, “Aliza don’t walk in<br />

there, he’s literally in the store right now, don’t do this Nancy Drew.”<br />

“What’s the worst that’s gonna happen? I’ll just walk in and look around<br />

while he’s up front and if I find anything odd I’ll tell you.”<br />

Peering from the door, I waited till the giant “gardening” shop owner<br />

walked up front again and I ran inside the dark room lit up only by blue tube<br />

lights over little plants, walking to a back counter I found a tray of unlabeled<br />

plants beneath a table. Footsteps started to approach the back of the store and<br />

I scrambled to get out, but then I heard the owner’s rapid voice.<br />

“What’re you doing in here?” Moving closer and faster toward me, he jogged<br />

to the back and I started speed-walking backwards out of the store still facing<br />

him and trying to talk.<br />

With a shaky voice I gave a vague lie, “Uh nothing, just the door was open<br />

and me and Mike wanted to buy flowers, bye.”<br />

He closed the heavy metal back door and never left it open again.<br />

Police cars started to patrol the lot every night, but once the sketchy activities<br />

came to a halt, the police officer decided to leave for good which allowed<br />

for the night time crime cycle to begin once again. Not being able to handle<br />

the stress of Subway, I complained to my friends and family constantly who all<br />

gave me the same solution to my problem, to quit.<br />

Fourth of July, the day the thirteen colonies regarded themselves as a new<br />

nation and gained their independence, and also the day I quit Subway and gained<br />

my independence. Experiencing my first job of working at Subway allowed me<br />

to understand that I should not have to do anything that makes me unhappy or<br />

unsafe, such as working somewhere with an awful environment or dealing with<br />

zany coworkers. While my two years flew by, I created a fake name, Joy, skeevy<br />

customers who asked for my name and number always got the name Joy and<br />

the number to a rejection hotline. I keep my fake name tag with me to remind<br />

myself that at one point in my life I had to create a fake name because of how<br />

irritated I became of work and now when I see the fake name tag I realize that<br />

ever since I quit my old Subway job, I am actually full of real joy.<br />

Short Prose<br />

25

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

Amanda Lu<br />

Grade 11<br />

North Allegheny Senior High School<br />

You are me. I am you.<br />

(Non-Fiction)<br />

A series of vignettes<br />

Today, I am one year old.<br />

Plop. Plop. My feet crash against the hard, gray floor.<br />

I count cracks. One. Plop. Plop. Two. Plop. Plop. Three.<br />

Careful, Xiaomei!<br />

Four. Plop. BOOM.<br />

My face crashes against the hard, gray floor.<br />

4<br />

Nainai, don’t go back to China. Stay a little longer here. Tell me a story. Nainai!<br />

She walks toward me and lies down. I place my head on her warm chest.<br />

She brushes my hair. She tells me about the Monkey King.<br />

I fall asleep.<br />

I wake up. The sun is shining on my face. The birds are chirping. I turn to<br />

my side, and there is no one there.<br />

4<br />

Amanda’s Chinese is well above her age group, my teacher muses.<br />

Baba smiles. Well, Chinese was her first language, and we only speak Chinese at<br />

home, so that is expected. What we really need to work on is her English.<br />

English will be easy to learn; you live in America after all. Just remember to<br />

never prioritize English over Chinese. Amanda is a Chinese girl, always was and<br />

always will be.<br />

Baba rolls his eyes light-heartedly. Of course.<br />

26

4<br />

Hi, I try to say to one of the pretty girls with yellow hair.<br />

Her eyebrows are furrowed. She looks at me with a confused expression.<br />

“Hell-loh.”<br />

“Hah-lo?” I spit out.<br />

She shakes her head. “HELL-LOH.” I try to pronounce the strange word<br />

once again. She continues to shake her head. Her yellow curls bounce up and<br />

down.<br />

She grabs my hand, and together, we run around the playground, communicating<br />

only through smiles and laughter.<br />

Short Prose<br />

4<br />

. . . and we’ll take you back to Tiananmen Square, your favorite spot. We will do<br />

anything to make your trip absolutely unforgettable. Nainai touches the screen with<br />

her hand and blows me a kiss. I respond by sticking my chubby cheeks on the<br />

webcam, and my grandma pretends to kiss her computer monitor.<br />

I’ll buy you lots of toys, Yeye interjects.<br />

Stop trying to compete with me. Xiaomei loves me the most, my grandma says,<br />

and we all laugh together.<br />

Before I say goodbye to Nainai, I tell Yeye to cover his ears.<br />

It’s true, Nainai, I tell her. I do love you the most.<br />

4<br />

There. Mama adds the finishing touch, a beautiful red rose petal, to my hair. I am<br />

wearing my bright red qipao in honor of the New Year. I feel like a million bucks.<br />

You look beautiful, Xiaomei. Your friends will be so jealous.<br />

I smile to myself because I know she’s right.<br />

She isn’t.<br />

When I get to school, I see countless kids pointing and laughing. They yell<br />

obscene comments toward me. I indignantly announce, “ching-chong isn’t even<br />

a word in any of the Asian languages!” but the kids continue to cruelly laugh.<br />

My friend lends me her big, black coat, and I drape it over the shiny red<br />

silk like a dark cloud of shame.<br />

When I come home from school, I storm off into my room. Mama asks me,<br />

how was school today? I don’t answer her.<br />

I rip the ugly red dress off my body and throw it onto the floor. Tears are<br />

27

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

streaming down my face, and through my fogged vision, the dress that used to<br />

shine so brightly looks like a sullen heap of red ash.<br />

The dress that used to be worth a million bucks was now worthless.<br />

4<br />

Baba, I cry, I don’t want to go to that stupid Chinese school. I want to play with my<br />

friends on Sunday.<br />

You have to. It’s not a choice. His tone is indignant, but I can sense a hint of<br />

sadness in his eyes, maybe even fear.<br />

Baba can be so stubborn sometimes. I wanted to fight back, but I knew it<br />

would lead nowhere. So, I had to get creative.<br />

4<br />

Your daughter is out of control, the Chinese teacher informs my father. She has<br />

been extremely disrespectful, not only to us, but also to her peers. She is one of our<br />

best pupils, but we will have to discontinue her education if she keeps up this behavior.<br />

I smirk at him and expect a snarky comment or look in response. However,<br />

I saw something entirely different from what I expected. There was no anger<br />

in his eyes.<br />

I immediately stop smirking.<br />

We walk to the car. He stares at the ground, while I pick at the skin on my<br />

hands. I figure he isn’t speaking to me because he is waiting to release all his<br />

rage during the 40 minute car ride home. When we reach our car, I compliantly<br />

leap in the backseat, thinking that if I act obediently now, he will spare me half<br />

the lecture. I brace my ears.<br />

There is no lecture.<br />

We ride back home in complete silence.<br />

That was the last time I ever went to Chinese school.<br />

4<br />

“Dad. Dad. Are you busy right now?”<br />

No, come in.<br />

He sits in his chair, feet propped on the desk. He’s focused on the keyboard<br />

and doesn’t look up.<br />

“Can I dye my hair brown?”<br />

No. Clack. Clack.<br />

28

“Why not?”<br />

The clacking stops, and he rests his hands on the table. He looks up<br />

incredulously. Amanda, why do you want to dye your hair?<br />

My cheeks start to burn. “Well, it’s just that . . .” I look up at my father,<br />

whose mouth is creased into a tight line. The disdain in his eyes is painfully<br />

obvious. “Just let me dye my hair!”<br />

He slams his fist down. Do you know how lucky you are to be born with<br />

beautiful, black hair? Why do you want to look like those white girls? You’re beautiful<br />

the way you are.<br />

Hot tears began to overflow and that stupid, all-too-familiar lump rose in<br />

my throat. Baba, I don’t want to look white! I just want a different hair color! Why<br />

is that so much to ask for?<br />

He shakes his head at me. You’re not dying your hair. Don’t ask me ever again.<br />

Short Prose<br />

4<br />

Amanda, you know Nainai hasn’t seen you in forever. Even worse: your Chinese is<br />

deteriorating by the second. Please, go back and just visit this summer. Do it for your<br />

family. Do it for Nainai.<br />

I sigh exasperatedly and violently throw my hands up in the air. “Baba, you<br />

KNOW I don’t have time to go back this summer! Stop pressuring me!”<br />

His face contorts into a look of hurt, and I feel a familiar lumpy sensation<br />

at the back of my throat. I look away, refusing to meet his eyes.<br />

He sulks away as I trace circles into the ground.<br />

4<br />

Everyone around me is getting absolutely wasted, and suddenly, I feel compelled<br />

to follow them. As I take a swig of my first drink, I hear someone mutter “chink.”<br />

Laughter follows.<br />

I walk around the crowded room. People stare back. They start to whisper to<br />

their friends. Some of them are pretty candid about their thoughts; they wonder<br />

aloud thoughts along the lines of “shouldn’t you be doing math homework?”<br />

and “we don’t serve dog here.”<br />

I lock myself in the bathroom with a bottle of alcohol. I tense up every time I<br />

hear laughter; it feels like the whole world is laughing at me. I feel a familiar<br />

burning sensation in the back of my throat. Maybe this time, it’s just the vodka.<br />

I stare in the mirror. An unfamiliar face stares back.<br />

29

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

Her dull, black hair casts a grim shadow over her face. Her brown eyes look<br />

lifeless and lacklustre like mud on the bottom of my shoes.<br />

Who the hell even am I?<br />

I wobble out of the bathroom. All the chatter around me transforms into a<br />

ringing sensation in my ears. I start to feel extremely dizzy, and I try to maintain<br />

my balance by holding onto the wall. It doesn’t work.<br />

I collapse on the ground. My head hits the hard, gray floor.<br />

The last thing I see before closing my eyes is the blurry shapes of the people<br />

surrounding me.<br />

It’s a house full of people, and somehow, I still manage to feel all alone.<br />

4<br />

“. . . and it freaking sucks, because all I want is to get rid of my stupid black hair.”<br />

“Seriously?” my best friend Mara lazily inquires. Her eyes are closed, and<br />

she is practically talking into her pillow. “Why?”<br />

“I just don’t like the way it looks, I guess.”<br />

Mara suddenly sits up in the bed, fully awake, so she can look me in the<br />

eyes. “Listen. Girl. We all have our insecurities. Yours is your black hair for<br />

some weird, unknown reason. Look, I shouldn’t have to tell you this, because<br />

it’s blatantly obvious, but your hair is gorgeous. It’s luscious, thick and it literally<br />

doesn’t look like hair; it looks like silk that has been dipped in dark black India<br />

ink. And I mean that one hundred percent as a compliment.”<br />

I smile to myself. Mara always found a way to make me feel better. “Do you<br />

really mean that, or are you just saying that because it’s 3 in the morning and<br />

you don’t want to deal with me complaining for the rest of the night?”<br />

She rolls her eyes. “Now you’re just fishing for compliments. To answer<br />

your question: it’s both. You’re annoying me, and I’m super tired. But seriously,<br />

your hair is gorgeous. You’re beautiful in general. I wish I had exotic features.<br />

I literally look like a cracker.” With that comment, she slides back under the<br />

covers and lands face-first into her pillow.<br />

I immediately run to the bathroom to examine my face in the mirror. The<br />

compliments she had half-assedly given me completely changed my perspective<br />

about beauty. I realized, in that moment, that it didn’t matter that I didn’t look<br />

like the people around me because I was beautiful in my own, unique manner.<br />

“Huh,” I say to no one in particular. “I guess I never thought of myself<br />

that way.”<br />

30

4<br />

How has your life been? How are your grades? Your friends? It’s been so long since we<br />

talked last. Nainai smiles at me and I smile back.<br />

I’ve been better. I miss you. I want to tell her more. I want to tell her about<br />

the guy I just kissed. I want to tell her about the research I’ve been conducting<br />

over the summer on bone marrow cells and the heart-wrenching but highly<br />

relatable young adult novel I just finished. Yet it was so hard to connect the<br />

words in my brain; it was so hard to communicate with my grandmother, even<br />

though Chinese was my first language.<br />

Are you still going to Chinese school? She continues to spew out questions that<br />

I can’t answer fast enough.<br />

I love you, I muster out for what seems to be the 50th time. The more and<br />

more I say it, the less significance it has.<br />

How tragic is it to be unable to communicate in your native language? My<br />

face burns with shame as I tell her I love you for the 51st time before hanging up.<br />

I should go back to China.<br />

Short Prose<br />

4<br />

Nainai overslept today.<br />

I open the door to her bedroom, and she laid there solemnly, her breathing<br />

barely audible. I tiptoe over, overly conscious of the plop plop sound my feet make.<br />

She laid in perfect solitude; the only movement was the subtle rise and fall<br />

of her chest. She looked so at ease: the world could end that minute and she<br />

would lay in the same position . . . so blissfully unaware.<br />

I feel an overwhelming wave of adoration for my lovely grandmother, and<br />

I can’t help but lean down and kiss her temple. Her eyes immediately flutter<br />

open, and upon seeing me, she smiles. A gaping hole took the place of where<br />

her fake teeth usually are.<br />

She was always extremely insecure about the way she looked without her<br />

fake teeth. It’ll scare you, she’d say when I’d tell her that she didn’t need to wear<br />

them all the time. It’ll just remind you how your old grandma is getting uglier and<br />

uglier with age.<br />

So it was then, that exact moment when Nainai flashed me her big, toothless<br />

smile, when I realized there was something so pure about her happiness—my<br />

mere presence had made her so giddy that she forgot about her insecurities.<br />

I wanted to reciprocate the love she had for me. I could tell her I love you,<br />

31

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

but in the grand scheme words mean nothing. I and love and you seemed just<br />

as meaningless and A and B and C.<br />

I felt uncomfortable. Guilty. Guilty for my lack of respect. Guilty because I<br />

was unable to cogently express my thoughts because of a language barrier that<br />

could have been avoided had I put more effort into learning Chinese. Guilty<br />

because I hadn’t come back to China.<br />

My eyes welled up with tears.<br />

My grandma, sensing absolutely none of my shame, gave me a timeworn<br />

smile. Xiaomei, she coos lazily, throwing her hands above her head. I am just so<br />

sleepy today. Come, lie down with me.<br />

One second, my head is on the pillow next to hers, and I am staring at the<br />

ceiling; next, I am trapped in her warm embrace. My head is strapped against<br />

her chest, and I am sobbing into her white cotton shirt. She runs her wrinkled<br />

fingers through my hair.<br />

My cries gradually wane, and I ask her to tell me a story. She nods enthusiastically<br />

and jumps into her favorite story: the first time I began to walk.<br />

We were at Tiananmen Square, right in front of the garden. It was around the<br />

beginning of spring and all the white lilies were finally starting to bloom.<br />

She vividly describes the pink flush of my chubby cheeks and my shrill<br />

laugh. She recalls the way I would tenaciously drag my stubby legs forward,<br />

determined to go as far as I can.<br />

You fell straight on your fat little face, and I was so worried about you that my<br />

heart could have stopped right there, she tells me. She grabs my hand and caresses<br />

my thumb. I expected loud sobs. How couldn’t I? You were a baby after all.<br />

But you started laughing, and I swear, it was the most beautiful sound I had ever<br />

heard in my life. You sounded like an angel.<br />

Oh, how her eyes lit up! With every word, a wrinkle would fade and her<br />

eyes would gain another sparkle. She looked so cheerful and vibrant, like the<br />

way she looked 15 years ago.<br />

That was so long ago, she tells me, yet I remember it all. I remember it like it<br />

was yesterday.<br />

Fresh, American air.<br />

My dad greets me at the Pittsburgh airport gates around 12:47 AM.<br />

We ride in silence.<br />

4<br />

32

So, he interjects, what was the most memorable part from your trip to China?<br />

I had to think about it, I really did. There were so many things I wanted<br />

to say: the priceless look of my grandparents’ faces when they saw me for the<br />

first time in three years; the annoyingly zealous salespeople who would say<br />

anything to get that 10% commission; the liveliness of the flourishing cities;<br />

walking to farmer’s markets within 1 kilometer and eating the freshest fruit<br />

nature had to offer; finally feeling like I belonged, because everywhere, people<br />

looked just like me. . . .<br />

A minute passes.<br />

“I guess I liked everything.”<br />

Short Prose<br />

4<br />

Today, I am seventeen years old.<br />

I stare in the mirror. This time, a familiar face stares back.<br />

Her raven black hair cascades over her shoulders like a waterfall of hope. I<br />

stare into her rich brown crescent-shaped eyes.<br />

You are beautiful, I tell her. Worthy. You are Chinese American. You are me.<br />

I am you.<br />

She smiles. I smile.<br />

33

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

Brianna Longo<br />

Grade 9<br />

Western Allegheny High School<br />

The Outcasts<br />

(Fiction)<br />

It was as cold as the North Pole, most would say. The winds were picking up<br />

with their howling gusts. The snow got heavier, and heavier as it fell onto the<br />

mountainside. It was hard to bear but I toughed through it, shacking the brutal<br />

snow off my back occasionally.<br />

Personally, I couldn’t stand these types of storms. The air and ground get<br />

to frigid for me. But in these circumstances, I had to travel as far away from<br />

them as I could.<br />

As the wind gusts got stronger, I flattened my ears against my head and<br />

curled my tail, so it resembled a long snake. When I looked up all I could see<br />

was white. I sighed. White. I hated the color white. It was too much of a dull<br />

color for me. That, and the fact that the dragon that had banished me had<br />

white markings.<br />

“Focus,” I scoffed to myself, “You have to get out of this storm.”<br />

As I put one leg in front of the other, I noticed that the snow on the ground<br />

got deeper, and deeper as I went on. But I had to be persistent. I couldn’t back<br />

down now, even though my whole body had to be suffering from hypothermal<br />

now.<br />

Suddenly, my legs stopped working and I collapsed in the confining snow. I<br />

sat there, alone, cold, and scared for a couple of minutes, with the giant clumps<br />

of snow rushing at my face. Minutes passed until I got way too cold for comfort<br />

and fainted. . . .<br />

When I woke up, I had no more snow on me and was in a cave. A dark cave.<br />

The only light that shown was from a sizzling fire right in front of me. When<br />

I looked up, I saw another dragon . . . twice the size of me.<br />

34

He was scary-looking and strange but muscular. When I got a good look<br />

at him, he looked familiar, like someone from my own tribe. He wasn’t at all<br />

different and was built the same as me, but with purple markings instead of<br />

blue, like mine. However, he looked mysterious. His head wasn’t bare. It had<br />

the remains of a dragon’s skull on it . . .<br />

Millions of questions raced through my mind the more I stared at him.<br />

“Your name.” The dragon demanded, interrupting my thoughts.<br />

I opened my mouth to speak, but nothing came out. I was truly terrified<br />

now.<br />

He sighed and glanced toward the entrance of the cave.<br />

“You know you shouldn’t be out in a snow storm,” he added.<br />

“Ye-Ye-Yes,” I stuttered.<br />

Then he turned back at me and flattened his ears and bitterly spat, “What<br />

tribe did you come from, and why are you here? A mountain that snows frequently<br />

is no place for a young dragon like yourself.”<br />

I shook my head, to rid it of my memories, and leaned toward the fire for<br />

warmth, ignoring the question the menacing dragon asked.<br />

The giant dragon stomped one foot that made the whole cave shutter in fear.<br />

“What is your name?” He repeated.<br />

“My name is Midnight,” I finally spoke.<br />

“Skull,” he said.<br />

“What?” I questioned.<br />

“My name is Skull,” he repeated. “Now, what tribe do you come from, and<br />

why are you here? You’re lucky you didn’t die out there.”<br />

“I come from the cave tribe,” I said as I sat up to meet his gaze.<br />

Skull made a toothy grin as I said the words. Then, licked his sharpened<br />

teeth. “The cave tribe you say?”<br />

“Yes.” I uncertainly stated.<br />

“I remember those days,” he paused and flexed his claws and crouched, ready<br />

to attack, “When those traitors turned on me, and banned me!”<br />

Then he jumped over the fire and pinned me to the ground with his claws<br />

flexed out as far as they could. I struggled to break free from his powerful grasp.<br />

“Tell me,” he snapped as he shoved me harder to the ground with his sharp<br />

outstretched claws,” Tell me what they said about me!”<br />

Then it hit me. He was the dragon from the stories! When we were young,<br />

we were taught a story about a purple marked dragon. When he was born, he<br />

was mean and cruel to the whole clan. As he got older, our mindful leader,<br />

Nightmare, gave him one last chance to prove himself. Then, one day he was left<br />

Short Prose<br />

35

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

alone in our egg nursery and blew them into bits. Every last egg . . . destroyed.<br />

Mothers and fathers cried, knowing that they would never be able to raise the<br />

little baby dragons inside each egg. As a punishment, he was banished into the<br />

unknown world, left to die and he was never heard from again.<br />

Of course, all the young dragons thought it was just another myth, but now<br />

I believe it one-hundred percent.<br />

I told him the story, hoping that it would be enough to save my life.<br />

After hissing the whole tale to him, he un-flexed his claws and leaped off<br />

me.<br />

As I got up, my bones ached from having so much weight on top of me.<br />

I looked down cowardly and shuffled my claws, while whispering, “None of<br />

us believed the story. We all thought it was just a myth. We. . . .”<br />

“Enough!” He snapped.<br />

After a moment passed I couldn’t help but ask, “Was it true? Were you that<br />

specific dragon?”<br />

“Yes,” he bellowed.<br />

“Really?” I questioned.<br />

“No”<br />

“What?”<br />

“Well . . . yes and no. I admit that I was bad as a kid, but I never struck<br />

those eggs. I promise you that.”<br />

“Then what happened?”<br />

He sighed, then spoke, “When I was little, I thought I was the best dragon<br />

ever because I was the only one who trained to become a leader. So, I started<br />

acting as if I was strongest leader ever. No one ever liked me for it, especially the<br />

leader. But when I got older, I became wiser and gave up the leader thing.” Skull<br />

paused and looked at the ground, “The leader still didn’t think I was changed.”<br />

He turned his head to look at my stunned eyes. “Therefore, I got blamed. I got<br />

blamed for the nursery exploding. Then I was banned forever from the tribe<br />

and moved to the mountains.” He paused, “I hate the color white.”<br />

“Funny,” I thought, “I do too.”<br />

“When I look out into the snow, I can’t help thinking of him. I hate him.”<br />

He made a low growling noise to show his anger.<br />

“But the legend said that you were the only one who was near the nursery.”<br />

I interrogated.<br />

“I was,” he confessed, “But I wasn’t the one who blew up the eggs.”<br />

He had a wild eye. Something in my gut told me he was crazy.<br />

36

“I’m not crazy,” he said as if he were reading my mind, “I’m telling you the<br />

truth.”<br />

There was a long period of silence, and both of us just sat, quietly, looking<br />

at each other.<br />

Until Skull spoke, “Why are you here? Why don’t you just go back home?<br />

You have no use here.”<br />

I looked down at the ground.<br />

“You did something wrong, didn’t you?” He asked.<br />

“Why are you asking?” I stood up and sneered.<br />

“Because,” he growled, “You very well might have a chance of living here.”<br />

I grunted, “You’re lonely, aren’t you? You just want me to tell you, so you<br />

could feel better about yourself!”<br />

When he looked at me, I knew I had said the truth. His eyes told me.<br />

“And you’re just trying to avoid the question because you feel guilty about<br />

what you have done!” He rambled back.<br />

I looked down at the rocky cave floor. We were both spitting the truth,<br />

but we hated to say it.<br />

“Fine,” I said, and took a long pause to gather up the courage to say what<br />

I had done. “I killed a dragon . . .”<br />

Skull chuckled.<br />

“It’s not funny!” I flared, “And I would have still been in the tribe if it<br />

wasn’t for you!”<br />

“Me?” He said, “Why me?”<br />

“Because,” I muttered, “The leader thought I’d become another you, so I<br />

got banned.”<br />

“So, what you’re telling me is that if I wasn’t born, you wouldn’t have been<br />

banned for killing another dragon?”<br />

“Well . . . you got away with it.”<br />

He looked at me, startled. “How do you know that?”<br />

“The story said it. It said you killed a dragon out of pure murder.”<br />

“Night deserved to die.” He said as his pupils turned into black slits. “He<br />

was a pure traitor. No good for anyone.” His wings flared with anger.<br />

I gulped. This dragon wasn’t the sweetest peach on the tree.<br />

“Get out of here while you still can,” my conscience urged me.<br />

“What else did they accused me of?” He screamed.<br />

I got up, didn’t say a word and headed towards the entrance. I put my head<br />

down, avoid eye contact with Skull’s blazing eyes.<br />

Short Prose<br />

37

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

I was almost at the cave entrance when a rock was hurled at me and hit<br />

me in the head.<br />

“Oww!” I whined.<br />

Then I looked down and realized the thing that hit me wasn’t a rock at all. It<br />

was a chewed bone that had daggers in it. Then another one hit me at my snout.<br />

“Quit it!” I exclaimed, “All I want to do is get . . .”<br />

At once, Skull hurled towards me and took me down with his powerful<br />

claws, ripping at my head.<br />

I blacked out. . . .<br />

When I woke up, a giant rock was crushing my body. I tried to move, but the<br />

rock was too heavy, and every time I did, and excruciating pain came from my<br />

fragile, cracked ribs.<br />

No one was in the cave. I was alone. I guessed it was a good thing because<br />

I had time to think of an escape plan.<br />

It was about an hour until Skull came in with a long, lizard-looking creature<br />

hanging from his jaws. He came towards me with it and dropped it at my snout.<br />

With a grimace he said, “Eat.”<br />

“No,” I blurted, “Why should I?”<br />

“Fine,” he said, “Have it your way,” and slid the thing right out of my reach,<br />

“Earn your share.”<br />

Then he stalked over to the roaring fire and plopped down next to it. All<br />

he did was stare at it.<br />

“How long has it been since you woke up?” He finally asked.<br />

“An hour,” I grunted, “Why did you put this bolder on me?”<br />

“Well I couldn’t have you go anywhere, could I?”<br />

“Get it off, now!” I screamed, “Get it off, or else . . . !”<br />

“Or else what?” He snorted, “You’ll call one of your precious friends to help<br />

you? If I wasn’t mistaken, I could have sworn you said you were banned from<br />

your tribe, and all your friends detested you.”<br />

“I never said my friends hated me,” I huffed while scrambling under a rock.<br />

“You never denied it before,” Skull smirked.<br />

After a short period of silence, I asked, “How long was I out?”<br />

“A night.”<br />

“And you had this giant rock on me the whole time?!”<br />

“No, “he retorted, “Just while I was hunting.”<br />

Skull stood up and headed towards the entrance.<br />

38

“Wait!” I cried.<br />

“What?” He declared.<br />

“Where are you going?”<br />

“Lonely, aren’t you?”<br />

“No! I just, well. . . .”<br />

“If you get hungry, there is food in front of you”<br />

I struggled under the rock, “I can’t reach it.”<br />

“Well,” he said, about to take off, “You should have thought about that before<br />

you rejected it,” and flew off into the white abyss.<br />

After a couple of minutes, I was so exhausted from trying to get the boulder<br />

off me that I slept.<br />

Short Prose<br />

When I woke up from my slumber, I noticed it was dark. It had to be midnight,<br />

and Skull still wasn’t back.<br />

I tried leaning myself a certain way to move the rock off, but the way I was<br />

positioned, only hurt me worse. I groaned. This rock will be the death of me. I<br />

pushed the rock further. Now, there was an excruciating pain in my wings and<br />

torso. I screamed, but no one heard me. The pain hurt so bad that tears ran<br />

down from my pained eyes.<br />

I pushed the rock over a little more. The worst pain I have ever felt only hurt<br />

for a couple of seconds because the rock rolled off me. I was free!<br />

Now I had my chance to leave. With Skull gone, and the entrance unguarded,<br />

I could escape.<br />

I crept up to the opening and poked my head out. The freezing snow fell<br />

on my face and I immediately launched backwards. The cave felt warm with<br />

the fire, but I had to leave. And quick before Skull had a chance to come back.<br />

I forced my body to enter the frigid cold snow storm. I ran up the mountain<br />

into where the snow was beating me. Luckily, I found a forest of trees on it.<br />

“I should take shelter there, so I won’t be so cold.” I thought.<br />

I ran toward the patch of trees. I was right. The trees provided warmth<br />

from the wind and snow.<br />

I ducked under a bush that still had green leaves on it. The snow was cold,<br />

but at least it wasn’t blowing in my face anymore.<br />

It took me a while to fall asleep in the bare cold because I was used to<br />

sleeping in warm caves. I yawned and wished that I hadn’t made my mistake.<br />

“Now what will I do?” I asked myself, “I can’t live out here alone.”<br />

But before I could think any further, my eyes shut, and I finally fell asleep.<br />

39

<strong>Ralph</strong> <strong>Munn</strong> <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Anthology</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

•<br />

I woke that morning and the snow had stopped, but I still felt cold. I got up and<br />

shook the snow off my body. Then I realized I was starving. I crept out of the<br />

bushes to search for food and the leaves began to shake.<br />

When I was fully out, I saw a tiny mouse run out of its burrow and onto<br />

the bright snow. It scampered close to me, and I crouched, waiting to pounce on<br />

the tiny, bug-eyed creature. Unfortunately, a big black and blue dragon in the<br />

middle of white snow stands out, and the mouse took one look at me and ran.<br />

“Darn-it!” I screamed as my stomach growled its anger.<br />

By then, I knew that all the prey heard my roar and ran away.<br />

“Well,” I told myself, “I’m not going to get food anytime soon.” Then I<br />

followed the peak of the mountain.<br />

While I trekked, I heard another mouse squeaking as it ran out of its hole.<br />

Once again, I crouched, ready to attack. But my stomach roared, and the mouse<br />

took one look at me and scattered back into its hole.<br />

As I was about to scream in frustration, I noticed a big, dark boulder sitting<br />

on the top of the mountain. Except it turned into a creature as it started<br />

running at me. I was about to run the other way, but the animal stopped, and<br />

it was Skull . . .<br />

“You’ll never get food the way you hunt,” he smirked, “You should have taken<br />

my food when I gave it to you.”<br />

All I could think was that I had to get away from him. “But I can’t,” I<br />

thought, “He took me down once and he can do it again.”<br />

“I can hunt for myself!” I yelled.<br />

“No, you can’t,” he retorted while jumping up on a snow-covered rock,<br />

“You’re not adjusted to this kind of lifestyle. Watch!”<br />

He blew a shock of lighting at the hole where the mouse went. The mouse<br />

came running out, and he quickly swiped it up with one claw and ate it alive.<br />

Then, he licked his blood-covered jaws, and stepped forward at me and growled.<br />

I knew he was about to attack, and I braced for it, but he jolted up in alarm, and<br />

turned his to the wind. Then flew off.<br />

It made me scared to see him like that. He looked scared, as if there were<br />

something else tougher out here. But I pushed on. The wind was picking up<br />

again, and there was no scent of food anywhere. I felt as if my stomach was about<br />

to eat my other organs.<br />

A blizzard picked up again, and I was once again looking for shelter to hide<br />

40

in. But the strong winds blew snow so hard in my face that I could only see a<br />

few feet in front of me.<br />

As I kept walking in the freezing snow, I saw a round grey blur in front of me.<br />

“A rock!” I silently babbled.<br />

I ran toward it and noticed that it had a small cave. Thankfully, it was big<br />

enough for me. I hunkered down in the small, dark place and sparked a fire<br />

from some sticks on the ground.<br />

It was difficult to sleep that night because all I could think of was how<br />

Skull said that I would never be able to survive out here if I didn’t adjust to the<br />

mountain lifestyle.<br />

“But, how did he?” I questioned.<br />

I tried to come up with ways to adjust, but nothing came to me. I was so<br />

used to the lifestyle I lived, that I couldn’t think of what Skull did to survive.<br />

The only thing I could think of was the hunting technique that Skull had<br />

showed me. But now that I thought about it, my stomach yelled, making me<br />

think of how I didn’t eat a morsel.<br />

I started to slide back into the cave, but it was so small that my claws<br />

showed, and snow started to blanket on them. However, I managed to sleep<br />

somehow.<br />

When the mists of the morning sun came out, I was relieved, yet hungry. I<br />

managed to survive a night without sleeping, but that meant I had to eat today<br />

or else I wouldn’t see another day.<br />

By now I thought my stomach wanted to leave my body in search of food.<br />

“It would probably have a better chance of finding it,” I sneered to myself.<br />

As I set off, my legs were so tired from last night that I thought they’d at<br />

least break today. All I wanted to do was take a nap, but my stomach refused<br />

me to do so.<br />

As I trudged along, one talon at a time, I finally saw a mouse.<br />