You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

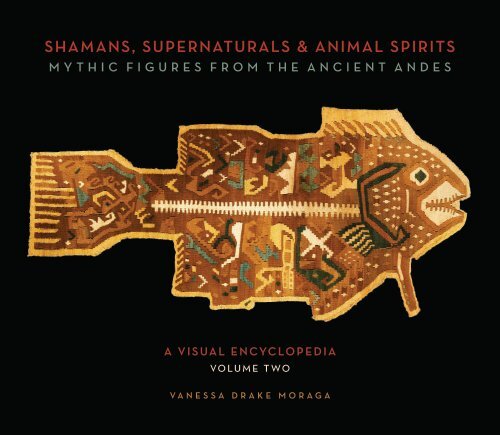

SHAMANS, SUPERNATURALS & ANIMAL SPIRITS<br />

MYTHIC FIGURES FROM THE ANCIENT ANDES<br />

A VISUAL ENCYCLOPEDIA<br />

VOLUME TWO<br />

VANESSA DRAKE MORAGA

Published by OLOLO Press<br />

P.O. Box 547<br />

Larkspur, California, 94977<br />

Copyright © 2016 by Ololo Press and Vanessa Drake Moraga<br />

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. The author<br />

and publisher retain sole copyright to this book. No part of <strong>the</strong> contents<br />

of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,<br />

digital, electronic or mechanical, including by any informational storage and<br />

retrieval system, without <strong>the</strong> written permission of OLOLO Press.<br />

All images: Private Collection<br />

Design: Vanessa Drake Moraga and Lindsey Brady<br />

Project Coordinators: Erik Jacobsen, Vanessa Drake Moraga<br />

Text Editor: Lucy Medrich<br />

Photography: Don Tuttle, Ralph Koch<br />

Bound in Berkeley California<br />

Published in two volumes.

SHAMANS, SUPERNATURALS & ANIMAL SPIRITS<br />

MYTHIC FIGURES FROM THE ANCIENT ANDES<br />

A VISUAL ENCYCLOPEDIA<br />

VOLUME TWO<br />

VANESSA DRAKE MORAGA

COLUMBIA<br />

ECUADOR<br />

PERU<br />

Amazon<br />

Lambayeque<br />

Moche<br />

Chimú<br />

BRAZIL<br />

ANDES<br />

Huarmey<br />

Chavín<br />

Recuay<br />

MAP OF ANDEAN CULTURES<br />

Chancay<br />

Pachacamac<br />

Paracas<br />

ANDES<br />

Wari<br />

Inka<br />

Ica<br />

Nasca<br />

Pukara<br />

Sihuas<br />

Lake<br />

Titicaca<br />

Tiwanaku<br />

BOLIVIA<br />

Pacific Ocean<br />

CHILE<br />

ARGENTINA

VOLUME ONE<br />

Map of Pre-Columbian Andean Cultures<br />

Timeline of Pre-Columbian Cultures<br />

CHAVÍN KARWA<br />

PARACAS • SIHUAS • NASCA<br />

Chavínoid Paracas<br />

Paracas Ocucaje<br />

Early Sihuas<br />

Paracas Necropolis<br />

Early Nasca<br />

Early Nasca<br />

Nasca, Nazca Valley<br />

Sihuas<br />

Sihuas-Nasca<br />

Nasca<br />

Nasca<br />

Nasca-Wari<br />

4<br />

6<br />

9<br />

29<br />

33<br />

59<br />

127<br />

183<br />

207<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

VOLUME TWO<br />

TIWANAKU • PUKARA<br />

WARI<br />

Provincial Wari<br />

Wari-Related Styles<br />

MOCHE WARI • HUARMEY<br />

CHIMÚ • LAMBAYEQUE<br />

CHANCAY<br />

PACHACAMAC<br />

ICA • SOUTH COAST CULTURES<br />

INKA<br />

Selected Bibliography and Sources<br />

10<br />

34<br />

97<br />

137<br />

165<br />

291<br />

306

ANCIENT ANDEAN CULTURES<br />

2500 BC 2000 BC 1500 BC 1000 BC<br />

HUACA PRIETA<br />

2400 BC, North Coast<br />

(Chicama Valley)<br />

CHAVÍN<br />

1200–300 BC, Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Highlands<br />

North, Central and South Coast<br />

Chavín de Huántar<br />

700-500 BC, South Coast<br />

(Bahía de Independencia)<br />

Karwa (Carhuas)<br />

KARWA<br />

8

500 BC 0 AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500<br />

PARACAS<br />

AD 600–100, South Coast<br />

(Paracas Peninsula, Pisco and Ica<br />

Valleys)<br />

SIHUAS<br />

300 BC–AD 700, Far South Coast<br />

(Majes Valley)<br />

200 BC–AD 200<br />

PUKARA Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Highlands<br />

(Lake Titicaca)<br />

100 BC–AD 800<br />

RECUAY North Highlands<br />

EARLY NASCA<br />

100 BC–AD 300, South Coast<br />

(Paracas Peninsula, Rio Grande Nazca Drainage)<br />

MOCHE<br />

100 BC – AD 700<br />

North Coast<br />

NASCA<br />

AD 200–600, South Coast<br />

(Paracas Peninsula, Rio Grande Nazca Drainage), Kawachi<br />

TIWANAKU<br />

AD 200–1000, Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Highlands<br />

Tiwanaku<br />

WARI<br />

AD 600–1000<br />

Highlands and Coast<br />

LAMBAYEQUE<br />

AD 1000–1476, Central Coast<br />

(Rimac and Lurin Valleys)<br />

AD 900–1470<br />

ICA South Coast<br />

AD 750–1350<br />

North Coast<br />

AD 950–1450<br />

CHIMÚ North Coast, Chan Chan<br />

PACHACAMAC<br />

AD 1150–1450<br />

Central Coast<br />

CHANCAY<br />

AD 1400–1532<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Highlands, entire Coast<br />

Cuzco, Machu Picchu<br />

INKA<br />

9

TIWANAKU<br />

PUKARA

Tiwanaku and Pukara Cultures<br />

Tiwanaku, Pukara, Wari: three ceremonial sites located in<br />

<strong>the</strong> central and sou<strong>the</strong>rn highlands were fundamental<br />

to <strong>the</strong> artistic florescence that occurred in <strong>the</strong> ancient<br />

<strong>Andes</strong> during <strong>the</strong> first millennium BC. Each is identified with<br />

<strong>the</strong> development of a textile aes<strong>the</strong>tic that served as a spectacular<br />

medium for religious iconography and <strong>the</strong> cultivation of<br />

cultural influence, as well as political or military force, across an<br />

enormous region.<br />

Situated at opposite ends of <strong>the</strong> Lake Titicaca Basin, Tiwanaku<br />

and Pukara seemingly represent sou<strong>the</strong>rn and nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

branches of a very early regional tradition that emerged around<br />

this massive high-altitude sea, and which gave rise to an archaic<br />

art style named Yaya-Mama.<br />

The Pukara culture (circa 200 BC-AD 200) is both slightly<br />

earlier and more enigmatic than that of Tiwanaku (circa AD<br />

200-1100). While <strong>the</strong> two cultures overlap in time as well as<br />

geographically, it appears that Pukara’s luster began waning just as<br />

Tiwanaku’s preeminence and ritual prestige were consolidating,<br />

a process that culminated around AD 400-500.<br />

Only vestiges of Pukara's monumental architecture survive<br />

today. But scatterings of figured carvings, metalwork and stone<br />

or pottery vessels found in <strong>the</strong> vicinity of Lake Titicaca indicate<br />

that Pukara was <strong>the</strong> genesis of core visual and cosmological<br />

<strong>the</strong>mes reworked by Tiwanaku and Wari artists. Indeed, if not<br />

<strong>the</strong> matrix culture, Pukara may represent <strong>the</strong> link between<br />

those two divergent highland traditions.<br />

In contrast, <strong>the</strong> urban grandeur and scope of Tiwanaku excited<br />

<strong>the</strong> admiration of <strong>the</strong> Inkas, Spanish conquistadors and 19thcentury<br />

European explorers alike for many centuries after its<br />

abandonment. Dominated by giant ritual pyramids known as<br />

<strong>the</strong> Akapana and Puma Punku, and a series of sunken courts,<br />

plazas, and palace compounds framed with impressive portals<br />

and fine stone facades, this magnificent complex was designed<br />

for large public ceremonies.<br />

Cult rites and communal feasts were most likely focused upon<br />

celestial and calendrical events or ancestral and mountain<br />

worship. The consumption of sacred botanicals (by dignitaries<br />

and shamans, at least) during <strong>the</strong>se ceremonies is now accepted<br />

fact.<br />

The wealth and power of Tiwanaku’s ruling elite (dynastic<br />

lords, royal families, a priestly caste?) were mirrored by <strong>the</strong> rich<br />

complexity of <strong>the</strong> architecture. A pan<strong>the</strong>on of mythological icons<br />

embellished <strong>the</strong> surfaces of temples and palaces. Supernatural<br />

personages and ancestral effigies portrayed on stone studded <strong>the</strong><br />

vast precincts. This mythical population is key to envisioning<br />

<strong>the</strong> Tiwanaku cosmos and interpreting Tiwanaku's artistic and<br />

symbolic legacy.<br />

Several works of sculpture are especially significant to <strong>the</strong><br />

consideration of textile imagery during this epoch. Among<br />

<strong>the</strong> most celebrated and revelatory of <strong>the</strong>se monuments, <strong>the</strong><br />

Sun Gateway or Portal presents a radiant deity posed on a<br />

stepped dais. Flanked by a retinue of winged attendants with<br />

bird and human heads, this cosmic being adopts a posture and<br />

insignia strongly reminiscent of <strong>the</strong> staff-bearing divinity of <strong>the</strong><br />

antecedent Chavín culture.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> staff is undeniably one <strong>the</strong> most important symbols<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Andean repertoire, its myriad connotations have yet to<br />

be fully catalogued—but <strong>the</strong>y far surpass <strong>the</strong> usual predictable<br />

12

association with spiritual or social supremacy. As in Chavín<br />

art, Tiwanaku, Pukara and Wari iconography suggest that this<br />

emblem may have shamanic significance. It appears to denote<br />

<strong>the</strong> transformative state of consciousness that was intrinsic to<br />

Andean ritual and thought. In certain contexts or imagery, it<br />

may even represent <strong>the</strong> catalyst—<strong>the</strong> San Pedro cactus—itself.<br />

this archaeologically unknown tradition prominently feature<br />

<strong>the</strong> face or form of <strong>the</strong> radiant Cosmic Deity. This imagery<br />

is exquisitely rendered in a naturalistic or pictorial style that<br />

does not generally engage <strong>the</strong> pronounced geometricization<br />

and distortion innate to Wari design, although it both preserves<br />

and amplifies essential Tiwanaku and Pukara archetypes.<br />

The Staff Deity surely gives form and persona to a deeply<br />

embedded, long-enduring, pan-Andean concept of what<br />

constitutes cosmic or creator power. It is also tenable that <strong>the</strong><br />

icon’s status in Tiwanaku, Pukara and Wari cultures reflects<br />

<strong>the</strong> lingering shadow and broad impact of Chavín shamanistic<br />

art and ritualism. Although this connection was posited by an<br />

earlier generation of Andean archaeologists and art historians<br />

(such as John Rowe or Alan Sawyer), recent scholarship has<br />

sidestepped this premise, not venturing to assert whe<strong>the</strong>r such<br />

a relationship exists or to establish its path of development and<br />

transmission.<br />

Mythological <strong>the</strong>mes expressed elsewhere in <strong>the</strong> Andean realm<br />

are similarly refracted in Tiwanaku iconography. An abstracted<br />

celestial figure embodying <strong>the</strong> sun, thunder, lightning, rain<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r wea<strong>the</strong>r or natural phenomena has a paramount<br />

role in <strong>the</strong> cosmologies of <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn sierra, altiplano and<br />

desert areas of present-day sou<strong>the</strong>rn Peru, Bolivia, nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Chile and Argentina. Tiwanaku’s wide sphere of interaction<br />

and influence encompassed that region (a counterpoint to <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn and coastal territories that were incorporated into<br />

<strong>the</strong> contemporaneous Wari empire). And many of <strong>the</strong> textiles<br />

produced by those cultures have made it possible to define <strong>the</strong><br />

attributes that differentiate <strong>the</strong> Tiwanaku and Wari aes<strong>the</strong>tics<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir weaving technologies.<br />

A more mysterious body of textiles, purportedly emerging <strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn highlands and far south coastal valleys of Peru, has<br />

also been linked to Pukara and Tiwanaku styles. Andeanists are<br />

still debating whe<strong>the</strong>r this material represents a provincial variant<br />

of, or even <strong>the</strong> precursor to, <strong>the</strong> art and iconography realized<br />

so majestically at Tiwanaku. The most impressive textiles <strong>from</strong><br />

The Gateway of <strong>the</strong> Sun at Tiwanaku, Bolivia.<br />

Adapted <strong>from</strong> Anton 1984, 103.<br />

13

133<br />

Band <strong>from</strong> a Tunic<br />

The Radiant Cosmic Deity (Staff God)<br />

Early Tiwanaku style, Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Highlands<br />

AD 200-700<br />

Camelid wool; tapestry weave<br />

10" x 12½"<br />

The celestial and mountain symbolism of Tiwanaku art,<br />

sculpture and temple architecture are condensed in <strong>the</strong><br />

figurative and abstract iconography of this textile.<br />

The large face ringed with a solar or thunderbolt corona<br />

represents an abbreviated (regional?) interpretation of <strong>the</strong><br />

Cosmic Deity, best known <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> iconic Sun Gateway.<br />

The modern title bestowed on <strong>the</strong> icon—<strong>the</strong> Staff God—<br />

hardly does justice to <strong>the</strong> totality of <strong>the</strong> metaphysical symbols<br />

and ideas packed into <strong>the</strong> figure, which had a profound and<br />

widespread impact on Andean ritual iconography during <strong>the</strong><br />

Middle Horizon period (circa AD 500-1100).<br />

Like a rising or setting sun, <strong>the</strong> radiant head emerges above<br />

a stepped form that recalls <strong>the</strong> terraces of <strong>the</strong> sacred Akapana<br />

pyramid in <strong>the</strong> ceremonial city. A quivering, comb-like motif<br />

embedded in this geometric shape similarly evokes <strong>the</strong> water<br />

that was channeled through <strong>the</strong> site or which flowed <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

nearby Choquepacha spring and o<strong>the</strong>r rivers originating in <strong>the</strong><br />

sacred mountains visible on <strong>the</strong> horizon. Ultimately, all pre-<br />

Columbian temples refer to such cosmologically significant<br />

peaks.<br />

Concurrently, however, <strong>the</strong>se two motifs are fused into an<br />

anthropomorphic figure that replicates <strong>the</strong> pose and features<br />

of <strong>the</strong> staff-bearing divinity depicted on <strong>the</strong> stone portal. The<br />

terraced platform becomes a patterned tunic or truncated body,<br />

and serpentine/bird motifs pointing down at each side suggest<br />

his staffs. Architectonic forms, also inlaid with bird faces, frame<br />

and separate each zone of <strong>the</strong> design, which was probably<br />

repeated along <strong>the</strong> span of a banded, red-ground tunic or shirt.<br />

The fragment belongs to a rare group of textiles that has been<br />

linked to a regional manifestation of <strong>the</strong> related, but distinct,<br />

Pukara and Tiwanaku traditions. Their origins are elusive, but<br />

<strong>the</strong> weavings are believed to have been unear<strong>the</strong>d in areas that<br />

lie closer to <strong>the</strong> Pacific coast than to <strong>the</strong> highlands around Lake<br />

Titicaca where those cultures arose. Their motifs and modes of<br />

representation, moreover, show affinity with certain early Sihuas<br />

<strong>the</strong>mes (see cat. 14). Yet how those cultures interacted—or<br />

which one might have been <strong>the</strong> originator of <strong>the</strong> iconography—<br />

remains problematic.<br />

The Staff Divinity concept was well established throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Andes</strong> long before Tiwanaku’s influence radiated south and<br />

west along llama caravan networks, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> trade in<br />

precious materials and prestigious goods. Tiwanaku’s visionaries<br />

appear to have blended that archaic icon with a sou<strong>the</strong>rn sierra<br />

cosmological figure who personified thunder and lightning<br />

(known later as Tarapaca or Tunupa).<br />

The present understanding is that <strong>the</strong> Sun Portal was installed<br />

at Tiwanaku after AD 500. Curiously, numerous "regional"-<br />

style textiles displaying related imagery predate <strong>the</strong> gateway and<br />

presumably could not have been inspired by it. There are several<br />

plausible explanations for this, including <strong>the</strong> possibility that<br />

<strong>the</strong> gateway we know today is actually older, that it replaced<br />

an earlier version or that textiles actually supplied <strong>the</strong> design<br />

template for this important ritual and calendrical monument. 1<br />

1 Margaret Young-Sanchez, ed., Tiwanaku: Ancestors of <strong>the</strong> Inkas (2004): 36, 49.<br />

14

15

16

134<br />

Fragment <strong>from</strong> a Tunic<br />

Solar Deity with Feline Traits and Cactus<br />

Headdress<br />

Tiwanaku style, Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Highlands<br />

AD 200-400<br />

Camelid wool; interlocking tapestry weave<br />

7½" x 10½"<br />

The charismatic personage portrayed on <strong>the</strong> Sun Portal at<br />

Tiwanaku was apparently envisioned in o<strong>the</strong>r forms as<br />

well. In this vibrant, visually complex interpretation, <strong>the</strong> solar<br />

face is reimagined as <strong>the</strong> countenance of a fierce cat, ei<strong>the</strong>r a<br />

puma or a jaguar (based on markings around <strong>the</strong> mouth). Small,<br />

realistically rendered spotted cats, standing in poses of alert<br />

tension, flank <strong>the</strong> focal image and reinforce <strong>the</strong> characterization.<br />

The connotations of <strong>the</strong> image are manifold. The Aymara word<br />

titi (as in Lake Titicaca or Titikala, <strong>the</strong> sacred rock located on <strong>the</strong><br />

Island of <strong>the</strong> Sun) means "puma." The terms underscores <strong>the</strong><br />

feline’s association with water, stone and <strong>the</strong> lake of "cosmic and<br />

human origins" among highland peoples. 1 Indeed, teardrops<br />

signifying rain or water flow <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> animal’s eyes.<br />

Rays and plumes encircling <strong>the</strong> face are delineated as winding,<br />

serpent-bodied creatures. Each features a different geometric<br />

pattern and shape, matched with <strong>the</strong> head of one of three<br />

animal archetypes corresponding to a specific cosmological<br />

domain. The striped “fea<strong>the</strong>rs" emerging at ear level terminate<br />

in a condor or raptor (Sky). The adjacent motif, rendered as a<br />

stepped triangle, features a puma head with a prominent snub<br />

nose and snail antennae (Earth). The third segmented form,<br />

shown <strong>from</strong> above, has <strong>the</strong> flat head and sinuous body of a<br />

snake (Water).<br />

The shamanic underpinning of <strong>the</strong> image is revealed by o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

symbols. Most significantly, a crown of cactus sprouts <strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> feline's head (detail below). This multi-trunk,<br />

columnar form is tipped with triangular motifs representing<br />

<strong>the</strong> white flowers that bloom at <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> night-blooming,<br />

hallucinogenic San Pedro cactus. This sign appears in o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Tiwanaku iconography, notably on an engraved monolith<br />

known as <strong>the</strong> Bennett Stela or Monolith.<br />

This mind-altering plant (typically consumed in a brew mixed<br />

with chicha, a fermented corn beer) is known to be an important<br />

aspect of Tiwanaku and Wari ritualism. The symbolic link<br />

between feline and cactus is an ancient one in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Andes</strong>, and<br />

can be traced to Chavín art. Clearly that association was true<br />

of Tiwanaku ritual and iconography as well.<br />

1 John Wayne Janusek, <strong>Ancient</strong> Tiwanaku (2008): 4.135<br />

San Pedro cactus symbol<br />

17

135<br />

Band<br />

A Procession of Supernatural Birds<br />

Tiwanaku style<br />

AD 200-400<br />

Camelid wool; tapestry weave<br />

3" x 15½"<br />

Stone lintels spanning <strong>the</strong> doorways and niches of Tiwanaku<br />

temples and palaces were carved with processions of<br />

supernatural llamas, pumas and birds. These fantastical figures<br />

adopt <strong>the</strong> same costumes, ritual accessories and sometimes<br />

stances of human dignitaries.<br />

Banded textiles and sashes echo <strong>the</strong> horizontal format and<br />

repeat imagery common to <strong>the</strong>se decorative friezes. The<br />

sculptural reliefs are known to have been inlaid with gold or<br />

painted <strong>the</strong> same vivid hues seen in <strong>the</strong> weavings; archaeologists<br />

have found evidence of murals created with red, blue, green,<br />

white and orange pigments. 1<br />

18

Tiwanaku dyers had mastered <strong>the</strong> more challenging, time-consuming process of dyeing wool with indigo. And a deeply<br />

saturated blue is <strong>the</strong> most distinctive and characteristic color of this highland weaving tradition, supplying a midnight-dark<br />

ground against which bright red and white details flicker as if caught by torchlight.<br />

In this motif, <strong>the</strong> wings, talons, beak and cere of an eagle or condor are placed on a stocky, elongated torso that is more<br />

quadruped than avian in form (although <strong>the</strong> harpy eagle <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> eastern rainforests actually shows this startling heft<br />

and solidity). This eccentric juxtaposition is not unique in Tiwanaku imagery. But <strong>the</strong> ambiguity of reference heightens<br />

<strong>the</strong> impression of mystery and o<strong>the</strong>rness, while expressing a complex set of mythological allusions. The hybrid figure<br />

carries an unrecognizable object (bag, woven amulet, trophy head?) in lieu of <strong>the</strong> staff displayed by <strong>the</strong> retinue of winged<br />

attendants depicted on <strong>the</strong> Sun Gateway, to which it must be related.<br />

1 John Wayne Janusek, <strong>Ancient</strong> Tiwanaku (2008): 146.<br />

19

136<br />

Band or Belt<br />

A Procession of Felines<br />

Tiwanaku or Pukara style<br />

AD 100-400<br />

Camelid wool; tapestry weave<br />

2½" x 25"<br />

The crouching pumas depicted in this narrow band are reminiscent of Pukara<br />

feline-shaped effigies and sculptural incense vessels that were used for burning<br />

ritual offerings. The cross motif apparently derives <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> jaguar's pelt markings<br />

(as in Chavín feline mortars), but in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn sierra it seems to have become a<br />

widely employed sign or cosmogram. The “raining" or “weeping" eye is similarly<br />

ubiquitous and symbolically charged.<br />

The composition is an undulating play of interlocking blues and greens. These<br />

harmonious hues surely had special connotations for being redolent of a greentinted<br />

gravel that was obtained <strong>from</strong> riverbeds in <strong>the</strong> sacred Quimsachata mountains<br />

and used to surface <strong>the</strong> terraces of <strong>the</strong> Akapana temple. 1 The meandering white<br />

outline separating <strong>the</strong>se two colors, which are so close in chromatic value, leads <strong>the</strong><br />

eye through <strong>the</strong> pattern field of geometric shapes.<br />

1 Alan Kolata, "The Flow of Cosmic Power," in Tiwanaku: Ancestors of <strong>the</strong> Inkas, ed. Margaret Young-Sanchez<br />

(2004): 100.<br />

20

21

137<br />

Fragment <strong>from</strong> a Tunic<br />

Avian Staff-Bearer<br />

Regional Tiwanaku style<br />

AD 400-800<br />

Camelid wool; interlocking tapestry<br />

14" x 11"<br />

This refined weaving, which interprets <strong>the</strong> eagle or condor<br />

incarnation of <strong>the</strong> staff-bearer in an exquisite range of<br />

colors and details, appears to have no equivalent in textile art<br />

or painted ceramics (according to <strong>the</strong> published literature). The<br />

rich color combination—especially <strong>the</strong> masterful manipulation<br />

of various shades of indigo blue—is, however, characteristic<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Tiwanaku aes<strong>the</strong>tic. The luminous palette may reflect<br />

a peripheral tradition (<strong>from</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Chile?) and <strong>the</strong> superb<br />

quality speaks to <strong>the</strong> elite context in which <strong>the</strong> garment was<br />

produced and worn.<br />

This unconventional image does not conform ei<strong>the</strong>r to <strong>the</strong><br />

Pukara style exemplified by previous entries, or to later Wari<br />

geometricization. The style of visualization is less formalized<br />

and more naturalistic—even painterly—enjoying remarkable<br />

freedom <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> rigid application of aes<strong>the</strong>tic canons evident<br />

in those o<strong>the</strong>r traditions.<br />

The design never<strong>the</strong>less has a modular structure, so that<br />

<strong>the</strong> figure and his regalia are composed <strong>from</strong> stacked blocks<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r of solid color or of beautiful geometric configurations<br />

featuring soft triangles, squares and circles.<br />

An unusual headdress, consisting of fea<strong>the</strong>rs or metal tabs(?)<br />

that diminish in size as it wraps over <strong>the</strong> head, is studded with a<br />

distinctive motif that evokes <strong>the</strong> white cup-shaped flower and<br />

fruit of <strong>the</strong> San Pedro cactus.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r details of <strong>the</strong> composition are in deteriorated condition.<br />

But several stand out as ei<strong>the</strong>r unique or tantalizing, including<br />

<strong>the</strong> green-and-red diamond-cross panel (a cloth or bag?) set<br />

on top of <strong>the</strong> staff; <strong>the</strong> flared, dentated shape of <strong>the</strong> tunic; and<br />

<strong>the</strong> ornamental discs dangling <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> waistband.<br />

22

23

138<br />

Fragment <strong>from</strong> a Tunic Band<br />

A Cult or Ritual Personage with Hallucinogenic Staffs<br />

Tiwanaku style<br />

AD 200-800<br />

Camelid wool; tapestry weave<br />

5¼" x 3¼"<br />

The naturalism of this image is exceptional within <strong>the</strong><br />

repertoire of Tiwanaku mythic icons, which are noted for<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir dense visual and symbolic intricacy. In addition, it supplies<br />

essential insight into <strong>the</strong> ritual practices of this culture, offering a<br />

rare glimpse of <strong>the</strong> role of “real" people such as shamans, priests<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>r cult participants in Tiwanaku religion and ceremony.<br />

The personage is presented in profile view, but with his torso<br />

twisted forward in order to best exhibit <strong>the</strong> staffs he carries in<br />

each hand. A puma emblem is ei<strong>the</strong>r tattooed or painted on<br />

his chest, or is part of <strong>the</strong> design of a patterned garment with a<br />

tie-dyed border or sash. Ornamental strands (beads? fea<strong>the</strong>rs?)<br />

dangle <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> ritualist’s ear and neck, while a serpentine<br />

crown with bird and plant ornamentation adds<br />

a supernatural touch to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rwise realistic<br />

portrayal.<br />

The most valuable information to be gleaned <strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> image lies in <strong>the</strong> depiction of <strong>the</strong> two staffs,<br />

which are decorated with <strong>the</strong> same concentric<br />

(tie-dyed?) circles as <strong>the</strong> waistband. Each emblem<br />

is capped with a distinctive magical plant symbol.<br />

The motif adorning <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> staff in front (as<br />

well as <strong>the</strong> headdress) is a stylized representation<br />

of <strong>the</strong> leaves and flowers of Anadenan<strong>the</strong>ra<br />

colubrina (widely known as vilca) (detail at left). Seeds extracted<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> giant pods of this tree were pulverized to produce<br />

a psychoactive snuff that was fundamental to Tiwanaku ritual.<br />

The pervasiveness and extent of this activity is evident <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

abundance of finely crafted snuff tables and paraphernalia that<br />

has been unear<strong>the</strong>d throughout <strong>the</strong> Tiwanaku world.<br />

The finial of <strong>the</strong> second staff (shown in back of<br />

<strong>the</strong> figure) represents a flowering San Pedro cactus<br />

(detail at right). The same motif is seen in <strong>the</strong><br />

corolla of <strong>the</strong> feline divinity portrayed in cat. 134,<br />

and is engraved as well on <strong>the</strong> torso of <strong>the</strong> giant<br />

ancestral effigy known as <strong>the</strong> Bennett Monolith<br />

that was enshrined at Tiwanaku.<br />

This explicit juxtaposition of <strong>the</strong> two plants<br />

sacred to Andean ceremonialism is of enormous<br />

significance—especially for determining <strong>the</strong><br />

meaning of <strong>the</strong> staff, which is a crucial emblem and<br />

multivalent signifier in both Tiwanaku and Wari<br />

iconography. The way <strong>the</strong> motifs are utilized here is fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

evidence that <strong>the</strong> staff placed in <strong>the</strong> hand of <strong>the</strong> winged Wari<br />

staff-bearer may not only designate a transcendent state or<br />

status, but in certain contexts, could depict <strong>the</strong> actual cactus<br />

itself.<br />

24

25

139<br />

Fragment <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Border of a Tunic<br />

Votive Head<br />

Tiwanaku style<br />

AD 160-430<br />

Camelid wool; interlocking tapestry weave, chain-stitch<br />

4¾" x 7¾"<br />

This fiercely compelling face is identical to motifs<br />

embellishing <strong>the</strong> borders and sleeves of a rare style of Early<br />

Tiwanaku or Pukara tunic. These ultra-prestigious garments<br />

were vehicles for <strong>the</strong> display of iconography based on <strong>the</strong><br />

celestial or solar cosmic being at <strong>the</strong> center of <strong>the</strong> Tiwanaku<br />

religious vision. They were undoubtedly worn by individuals of<br />

<strong>the</strong> highest social or spiritual rank.<br />

In one extant tunic, 1 <strong>the</strong> heads are arranged along <strong>the</strong> lower<br />

edge—<strong>the</strong> typical location for a trophy-head border in Andean<br />

textile design. They may very well symbolize votive heads<br />

dedicated to <strong>the</strong> deity or his human intercessors. But <strong>the</strong>ir eyes<br />

are open and piercing, suggesting life ra<strong>the</strong>r than death.<br />

Like this example, <strong>the</strong> heads portray males of ambiguous,<br />

but evidently high, status. The characters wear headdresses<br />

composed of tipped, fan-shaped elements resembling fea<strong>the</strong>rs,<br />

which were indeed often incorporated into Andean head<br />

adornments. But <strong>the</strong> form also replicates <strong>the</strong> centerpiece of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cactus Crown worn by <strong>the</strong> deity in cat. 134, and based on<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r iconographic evidence <strong>from</strong> this tradition, it is feasible<br />

that it may represent a large, stylized cactus flower instead.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>y sport similar headgear and ear discs, each of <strong>the</strong><br />

five figures repeated on that related tunic is distinguished by<br />

a different face design. These striking compositional elements<br />

inject visual variety and asymmetry into <strong>the</strong> pattern sequence;<br />

<strong>the</strong>y may also convey information about <strong>the</strong> individuals<br />

portrayed.<br />

For while this particular face is isolated and cannot be<br />

considered as part of a larger grouping, <strong>the</strong> hook symbol<br />

emblazoned on his check is also seen on a head anchoring <strong>the</strong><br />

lower corner of <strong>the</strong> published tunic. The coincidence suggests<br />

that both textiles were produced in <strong>the</strong> same workshop, or that<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir designs were standardized. However, it is also credible<br />

that <strong>the</strong> markings are ethnic or social signifiers.<br />

The image <strong>the</strong>refore supports multiple interpretations. It<br />

may represent <strong>the</strong> severed head of a warrior or o<strong>the</strong>r human<br />

sacrifice. It could also denote any one of <strong>the</strong> many groups<br />

incorporated, ei<strong>the</strong>r through defeat or peacefully, into <strong>the</strong><br />

Tiwanaku sphere. Or it may stand for one of <strong>the</strong> lineages or<br />

groups (ayllus) comprising <strong>the</strong> community in which <strong>the</strong> tunic<br />

was used or displayed.<br />

1 The related tunic is published and discussed in Margaret Young-Sanchez, ed.,<br />

Tiwanaku: Ancestors of <strong>the</strong> Inkas (2004): 41-43.<br />

27

140<br />

Shaped Sash or Votive Panel (partially complete)<br />

<strong>Mythic</strong>al Fox<br />

Pukara style, Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Highlands<br />

200 BC-AD 200<br />

Camelid wool (warp and weft); tapestry weave<br />

5" x 8½"<br />

Asmall body of inventively shaped tapestry weavings has<br />

been instrumental in defining <strong>the</strong> Pukara textile style,<br />

which is considered to be influential in <strong>the</strong> development of<br />

Tiwanaku art. They are believed to have been found at some<br />

distance <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pukara ceremonial zone north of Lake<br />

Titicaca, however—ei<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> western highlands, <strong>the</strong> south<br />

coast or <strong>the</strong> upper coastal valleys of <strong>the</strong> Arequipa region. Only<br />

some half-dozen pieces are documented, which are among <strong>the</strong><br />

most innovative and puzzling textiles in <strong>the</strong> Andean tradition.<br />

The textiles are also recognized for being <strong>the</strong> earliest evidence<br />

of <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> interlocking tapestry technique, which became<br />

<strong>the</strong> foundation of <strong>the</strong> Wari tunic style. 1<br />

The panels are of unknown purpose, and were possibly made<br />

as talismans or accessories worn as part of a ceremonial or<br />

ritual ensemble. The imagery suggests <strong>the</strong>y were associated<br />

with trophy-head cult activities and beliefs.<br />

The textiles, which resemble two-dimensional reliefs or<br />

sculptural plinths executed in cloth, represent a striking<br />

syn<strong>the</strong>sis of form and image. The contoured weavings, entirely<br />

selvedged on all sides, outline <strong>the</strong> forms of mythical figures<br />

or animals. Details such as feet, hands, face and staffs or spears<br />

project into space. The curvilinear, irregular shape reflects <strong>the</strong><br />

use of a single continuous warp, although whe<strong>the</strong>r this was<br />

determined by <strong>the</strong> shape of <strong>the</strong> loom or some o<strong>the</strong>r approach<br />

is not clear (see Conklin 1983 for technical analysis).<br />

This panel is only partially intact but can be compared to<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r extant, complete version. 2 Although <strong>the</strong> head is<br />

missing, <strong>the</strong> upright brushy tail appears to belong to a fox. In<br />

highland lore, <strong>the</strong> canid is actually regarded as <strong>the</strong> “younger<br />

bro<strong>the</strong>r" of <strong>the</strong> puma, but it has its own specific mythological<br />

associations within <strong>the</strong> feline symbolic complex. In <strong>the</strong> related<br />

piece, moreover, <strong>the</strong> animal is depicted holding a spear and<br />

ferrying a severed head (embellished with real human hair) in<br />

its mouth. Fortunately, one dramatic detail <strong>from</strong> that image is<br />

still preserved here, i.e., <strong>the</strong> headless, naked body of <strong>the</strong> victim<br />

draped over <strong>the</strong> rump of <strong>the</strong> predator.<br />

Ferocity is implicit, and this fox is evidently a supernatural<br />

sacrificer or agent of death. The skeletal ribs drawn on <strong>the</strong><br />

prone human figure typically also denote shamanic beings, as<br />

well as <strong>the</strong> dead (especially in Early Nasca iconography, which<br />

seems to have ties to Pukara). The bones apparently signal <strong>the</strong><br />

altered or transcendent state brought about by a ritual killing.<br />

The peculiar addition of an open beak to <strong>the</strong> stump of <strong>the</strong><br />

victim’s neck, conjuring a stylized bird head, underscores this<br />

message.<br />

The male victim appears to be a defeated enemy (ironically,<br />

he, too, carries severed heads in both hands). The pointed tip<br />

of an arrow or dart (top right) is <strong>the</strong> only surviving element<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> “captured" bundle of weapons depicted on o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

versions. This <strong>the</strong>me appears elsewhere in Pukara imagery, a<br />

strong indication that ethnic conflict played a role in <strong>the</strong> rise<br />

of this highland culture.<br />

1 William Conklin, "Pucara and Tiahuanaco Tapestry: Time and Style in a Sierra<br />

Weaving Tradition," Nawpa Pacha 21, (1983).<br />

2 Margaret Young-Sanchez, ed., Tiwanaku: Ancestors of <strong>the</strong> Inkas (2004) 39-40: Fig 2.21.<br />

29

141<br />

Shaped Sash or Votive Panel<br />

<strong>Mythic</strong>al Caiman<br />

Pukara style, Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Highlands<br />

200 BC-AD 200<br />

Camelid wool (warp and weft); tapestry weave<br />

4½" x 20"<br />

The connection between Chavín and Tiwanaku iconography—especially <strong>the</strong><br />

vision of a supernatural figure with staffs—is acknowledged by many Andean art<br />

historians. However, knowledge is lacking as to how this fundamental <strong>the</strong>me (and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Chavín ideas) might have been transplanted, or later revived, across such an expanse<br />

of time and space. Unless such a conception was already widely and deeply embedded<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Andean imagination, <strong>the</strong> links in <strong>the</strong> chain, indeed <strong>the</strong> putative pathway of<br />

transmission <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> central to <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn highlands, remains to be traced.<br />

None<strong>the</strong>less, this rare, shaped Pukara textile also implies familiarity with <strong>the</strong> stone<br />

obelisk depicting a pair of mythical caimans that was installed at <strong>the</strong> ceremonial center<br />

of Chavín de Huántar many centuries before. Chavín was still regarded as an oracle<br />

center as late as <strong>the</strong> 17th century, so pilgrimage to that shrine by many generations<br />

of pre-Columbian peoples might have played a part in spreading Chavín symbolism.<br />

30

Caiman divinities were also represented in <strong>the</strong> painted hangings<br />

found at Karwa on <strong>the</strong> south coast of Peru, i.e., <strong>the</strong> very region<br />

that subsequently developed a relationship with <strong>the</strong> Titicaca<br />

Basin cultures.<br />

In this unique shaped, talismanic weaving, 1 which abounds<br />

with inexplicable, surrealist details, <strong>the</strong> caiman has been<br />

integrated with a staff or spear-carrying human figure. A<br />

macabre headdress composed out of two severed human arms<br />

with oversized grasping hands, and jaguar markings around <strong>the</strong><br />

fanged mouth, confirm an inner rapacity. The fusion speaks of<br />

shamanic conversion and dangerous powers.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> elongated form and tail fin of <strong>the</strong> plant-laden Chavín<br />

icon are echoed in this design, <strong>the</strong> vertebrae of <strong>the</strong> spinal<br />

column, as well as <strong>the</strong> joints, are re-interpreted as skulls. O<strong>the</strong>r<br />

fleshy heads stud <strong>the</strong> creature’s body like so many kernels or<br />

fruits. The conjunction of <strong>the</strong> two motifs connotes life out of<br />

death, for in pre-Columbian Andean thought, bone and seed<br />

are visual and symbolic analogies. More tellingly here, an<br />

element attached to <strong>the</strong> slings hanging <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> elbow and<br />

etched on <strong>the</strong> cheek appears to refer simultaneously to <strong>the</strong><br />

trance-inducing vilca plant and a corncob (signifying both a<br />

food crop and a fermented beverage drunk ceremonially).<br />

1 William Conklin, "Pucara and Tiahuanaco Tapestry: Time and Style in a Sierra<br />

Weaving Tradition." Nawpa Pacha 21 (1983): 1–44.<br />

31

142<br />

Band<br />

Dismembered Warrior<br />

Pukara style<br />

Circa AD 100-400<br />

Camelid wool; tapestry weave with paired warps<br />

7¾" x 1⅓"<br />

This band shows a striking likeness to several Pukara and Tiwanaku stone<br />

sculptures <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> environs of Lake Titicaca, notably a stela depicting <strong>the</strong><br />

disarticulated form of a male warrior. 1 Here <strong>the</strong> similarly disjointed head, arm<br />

and leg of <strong>the</strong> figure are outlined on a rust-red background in a style that<br />

strongly recalls <strong>the</strong> faceted surface of <strong>the</strong> carved stone.<br />

The date attributed to that stela, circa 200 BC-AD 200, overlaps with <strong>the</strong><br />

probable date of this tapestry band. Although it is not clear which version of this<br />

disconcerting image—stone or cloth—represents <strong>the</strong> prototype, <strong>the</strong> two works<br />

evidently refer to <strong>the</strong> same myth or history. This is borne out by <strong>the</strong> identical<br />

attributes of <strong>the</strong> individual portrayed. Both warrior-victims feature an angular,<br />

serpentine design painted or tattooed around <strong>the</strong>ir eyes and a distinctive long,<br />

pointy braid or lock of hair, which suggest ethnic or group identifiers. The<br />

crook of <strong>the</strong> arm, <strong>the</strong> spread hands and <strong>the</strong> anklets, wristbands, and trophy-head<br />

joints are depicted in similar fashion.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong> knife tucked into <strong>the</strong> decorated sheath or band wrapped around<br />

<strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> thigh reflect <strong>the</strong> weaver’s greater ability to employ color to<br />

incorporate additional details (which may very well have been applied to <strong>the</strong><br />

stone rendering with paint).<br />

The grisly act or history that can be inferred <strong>from</strong> this tableau describes <strong>the</strong><br />

kind of ritualized violence and sacrificial practices that were common in<br />

pre-Columbian warfare. Human bodies, body parts and skulls were also<br />

entombed as dedicatory offerings under important buildings at both Tiwanaku<br />

and Pukara.<br />

Drawing adapted <strong>from</strong><br />

Young-Sanchez 2004, fig. 3.8.<br />

1 The sculpture, found in Moho on <strong>the</strong> eastern lakeshore, is now in <strong>the</strong> collection of <strong>the</strong> Peabody<br />

Museum, Cambridge, MA, and is published in Margaret Young-Sanchez, ed., Tiwanaku: Ancestors of <strong>the</strong> Inkas<br />

(2004): fig. 3.8.<br />

32

33

WARI

Wari Culture<br />

The Wari Empire, which took shape in <strong>the</strong> Ayacucho<br />

Valley of <strong>the</strong> central sierra around AD 500 and<br />

expanded outward over <strong>the</strong> following five centuries,<br />

was Tiwanaku's complement in every respect. Indeed, <strong>the</strong><br />

two cultures were initially thought to be branches of a single<br />

tradition emanating <strong>from</strong> Tiwanaku. Today's more nuanced<br />

perspective recognizes that each culture developed concurrently<br />

but independently. They coexisted for much of this period<br />

as distinct, complex societies with separate domains—and<br />

dynamics—of influence and control.<br />

The exact nature of <strong>the</strong> relationship or alliance between <strong>the</strong>se<br />

two regional powers remains obscure, however. Never<strong>the</strong>less,<br />

both <strong>the</strong> Wari and <strong>the</strong> Tiwanaku cultures forcefully drove<br />

<strong>the</strong> religious and artistic phenomena that swept <strong>the</strong> Andean<br />

region between AD 400 and 1000, conveyed most effectively<br />

by textile art.<br />

Unlike <strong>the</strong> rich body of monumental sculpture and friezes<br />

portraying cosmological imagery preserved at Tiwanaku, <strong>the</strong><br />

palatial, ritual, and administrative buildings in Wari cities and<br />

settlements have yielded no public art. Yet Wari textiles and<br />

painted pottery discovered in highland and coastal locations<br />

alike document <strong>the</strong> influx, rapid adaptation and subsequent<br />

transformation of Tiwanaku's religious and artistic <strong>the</strong>mes.<br />

Wari did not merely appropriate this sacred or prestigious<br />

iconography. It clearly subscribed to <strong>the</strong> cosmic vision,<br />

spreading its version via military domination across southcentral<br />

and nor<strong>the</strong>rn Peru. Why, or how, it came to do so is<br />

unresolved.<br />

That cosmology focused on <strong>the</strong> resplendent Cosmic or Staff<br />

Deity (Tiwanaku's Sun Gateway God) and his coterie of<br />

fantastical animal or human retainers. For unknown reasons,<br />

Wari artists employed different media for expressing this<br />

imagery. The Staff Deity is painted on pottery vessels, especially<br />

those that were used for communal feasting and rituals; most<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se ceramics were found ceremonially smashed. However,<br />

this paramount divinity never appears in <strong>the</strong> designs of <strong>the</strong><br />

tapestry tunics that were Wari's highest-status garments and its<br />

most emblematic art form. Instead, <strong>the</strong> standardized format of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se textiles concentrates on <strong>the</strong> staff-bearing attendant in his<br />

many incarnations.<br />

The extensive repertory of staff-bearer icons yields numerous<br />

exceptions and idiosyncratic variations. But generally, this<br />

mythical personage is shown in profile on bended knee, as if<br />

kneeling, running or flying. The head is frequently contorted<br />

or twisted upward as if in a state of trance or transcendence.<br />

Whatever its outward guise, <strong>the</strong> shamanistic figure is usually<br />

winged and laden with a heavy crown that is more like a raft<br />

of symbols than a literal headdress. In fact, <strong>the</strong> figure is strongly<br />

allegorical and most of its attributes and decorative motifs<br />

seemingly serve a descriptive purpose.<br />

Wari image-makers incorporated a Ritual Sacrificer into this<br />

core mythical group. (In some renderings <strong>the</strong> character is<br />

conflated with <strong>the</strong> staff-bearer, who thus displays <strong>the</strong> victim<br />

or his severed head.) This frightening individual is typically<br />

endowed with <strong>the</strong> fanged mouth, claws or markings of a<br />

predatory cat; more rarely, <strong>the</strong> personage may be represented<br />

as a llama (identified by its elongated skull and cloven hoof) 1 or<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r ferocious creature <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Andean bestiary.<br />

Staff-bearers assume <strong>the</strong> upright stance of human beings, but<br />

tend to occupy different places along <strong>the</strong> spectrum of human/<br />

animal forms. Certain figures are transitional; <strong>the</strong>y acquire beaks<br />

or fangs but retain human feet and hands. This intermediary<br />

36

state clearly ei<strong>the</strong>r alludes to a shamanic transfiguration or<br />

animal/human duality, or describes metaphorical powers and<br />

traits borrowed <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> animal realm that serve to reinforce<br />

<strong>the</strong> wearer's rank, role or special qualities.<br />

Scholars have made progress unraveling <strong>the</strong> connotations of<br />

recurrent symbols (although <strong>the</strong>re is not always consensus<br />

about <strong>the</strong>ir meanings). The motifs are all <strong>the</strong> more cryptic<br />

for <strong>the</strong> paucity of cultural and historical information, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> incomplete archaeological record. But as highlighted in<br />

<strong>the</strong> individual captions in this catalogue, <strong>the</strong>y include stylized<br />

plants, human trophies and objects or materials imbued with<br />

special magical or spiritual properties for Andean peoples (such<br />

as fea<strong>the</strong>rs or fire).<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> most significant of <strong>the</strong>se visual signs are ones<br />

codifying <strong>the</strong> sacramental plants with hallucinogenic<br />

properties—San Pedro cactus and Anadenan<strong>the</strong>ra colubrina—<br />

that were crucial to Andean ritualism and <strong>the</strong> altered states<br />

of mind such rites promoted. Similarly, ano<strong>the</strong>r hi<strong>the</strong>rto<br />

mysterious motif is now understood to represent <strong>the</strong> heart,<br />

lungs and trachea of a person who has been ritually killed or<br />

decapitated, usually in connection with fertility cults. 2<br />

The deciphering of this arcane symbology is far <strong>from</strong> complete,<br />

and will add immensely to our understanding of Wari culture<br />

and ritual as it proceeds. The abstract Wari aes<strong>the</strong>tic, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

hand, is more readily analyzed for its unique formal properties,<br />

which were rigorously observed and creatively manipulated by<br />

Wari weavers. Despite <strong>the</strong> modern viewer's appreciation for this<br />

virtuoso geometric aes<strong>the</strong>tic, Wari abstraction is intellectually<br />

and perceptually challenging.<br />

The ordering of <strong>the</strong> figures and <strong>the</strong> organization of visual space<br />

are generally predetermined by Wari artistic canons, which<br />

none<strong>the</strong>less admit some variety, as well as locally derived ideas<br />

about format and <strong>the</strong>me. The large, squarish tunic generally<br />

consists of two rectangular panels, folded in half and sewn<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> center and at each side. This plane is generally<br />

The Staff-Bearing Attendant on <strong>the</strong> Gateway of <strong>the</strong> Sun at Tiwanaku.<br />

Adapted <strong>from</strong> Anton 1984, 109.<br />

37

subdivided into multiple symmetrical columns of varying<br />

width and number. Patterned bands alternate with areas of<br />

solid color, usually gold or red. (A small number of tunics<br />

replace this standardized layout with atypical configurations,<br />

all-over patterning or even large-scale figuration.)<br />

The primary motif—whe<strong>the</strong>r a staff-bearing character or<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r supernatural or a profile or frontal face, or an abstract<br />

element like a spiral or fret—is repeated within all <strong>the</strong> vertical<br />

bands. And it is <strong>the</strong> dynamic, malleable treatment of this figure<br />

that is so visually arresting. The figure is typically subjected to<br />

a series of artistic conventions that result in its compression,<br />

expansion, inversion or reversal. The process ultimately leads to<br />

<strong>the</strong> total distortion of its modular parts and overall form.<br />

Each motif is composed using a stock vocabulary of rectilinear<br />

and curvilinear figurative or schematic elements. This<br />

constructivist approach to creating a figure out of geometric<br />

blocks—which are modified in shape, in scale and by color,<br />

according to an internal pattern scheme—yields mosaic-like<br />

designs. The compositions range markedly in <strong>the</strong>ir degree of<br />

visual cohesion and legibility—even to <strong>the</strong> point of visual<br />

fracture, when <strong>the</strong> geometricization and distortion are pushed<br />

to an extreme.<br />

The orientation of <strong>the</strong> motifs in <strong>the</strong> patterned bands also<br />

follows an internal logic established by <strong>the</strong> weaver or weaving<br />

workshop. The repeat figures are juxtaposed, inverted, doubled<br />

or paired in ingenious ways. Depending on whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

read on <strong>the</strong> vertical axis, as horizontal rows or in diagonal<br />

arrangements, some figures are shown twisting in opposite<br />

directions, for example, while o<strong>the</strong>rs may face <strong>the</strong> same way, or<br />

mirror each o<strong>the</strong>r across <strong>the</strong> center seam.<br />

This pattern of alternation is fur<strong>the</strong>r complicated by <strong>the</strong><br />

rhythmic magnification and condensation of <strong>the</strong> smaller<br />

components or details of <strong>the</strong> design (such as a wing, staff,<br />

head or headdress). These shifts visibly alter <strong>the</strong> proportions,<br />

delineation and clarity of <strong>the</strong> overall image.<br />

If this process were not sufficiently confounding, it also<br />

intersects with a sophisticated use of color, which is applied in<br />

predictable combinations that recur in a fixed number, order<br />

and direction across <strong>the</strong> entire compositional field of <strong>the</strong> tunic.<br />

Even though <strong>the</strong>se color clusters, or blocks of associated colors,<br />

are repeated at regular intervals, <strong>the</strong>y are aligned and staggered<br />

on parallel diagonal lines that may converge, cross or move<br />

up and down in opposite directions. This progression can be<br />

mapped graphically, as Susan Bergh has done. But because <strong>the</strong><br />

faceted surface and prismatic color usually mask <strong>the</strong> underlying<br />

order, it not easily distinguishable by <strong>the</strong> viewer. Moreover,<br />

randomly placed and arbitrary color substitutions, or deviations<br />

in <strong>the</strong> hue of any one element, large or small (an aes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

predilection common to Andean weavers <strong>from</strong> all cultures and<br />

periods), may fur<strong>the</strong>r disrupt <strong>the</strong> sequence, thus baffling most<br />

readings. (This type of analysis is particularly difficult to grasp<br />

when <strong>the</strong> textile is incomplete or fragmentary.)<br />

Why most Wari tunic iconography focuses almost exclusively<br />

on <strong>the</strong> attendant staff-bearer, ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> primary waka<br />

or Cosmic/Creator Deity, is unanswerable. It may have to<br />

do with <strong>the</strong> political and military nature of <strong>the</strong> Wari state.<br />

Perhaps this imperial society took on <strong>the</strong> role of proselytizer<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Tiwanaku (or highland) religious vision. Or, possibly,<br />

its officials saw <strong>the</strong>mselves as members of a “divine legion"<br />

who paid veneration to <strong>the</strong> Cosmic Deity and sought to direct<br />

<strong>the</strong> resources of <strong>the</strong> larger Andean realm toward it (while<br />

benefitting <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> power and control over such resources).<br />

The result of this cultural imperative was a powerful artistic<br />

vision that encoded its message of shamanistic transcendence<br />

in a collectively created visual and symbolic language that left<br />

room for individual genius.<br />

1 Susan E. Bergh, “Tapestry Woven Tunics," in Wari. Lords of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ancient</strong> <strong>Andes</strong>, ed.<br />

Susan E. Bergh (2012): 166.<br />

2 Anita Cook, “The Coming of <strong>the</strong> Staff Deity," in ibid., 112-113.<br />

TheWinged, Avian Staff-Bearer on <strong>the</strong> Gateway of <strong>the</strong> Sun at Tiwanaku.<br />

Adapted <strong>from</strong> Anton 1984, 107.<br />

38

39

143<br />

Fragment <strong>from</strong> a Tunic<br />

Staff-Bearer with Cactus Motifs<br />

Wari culture<br />

AD 600-900<br />

Camelid wool; interlocking tapestry weave<br />

7" x 5"<br />

The Tiwanaku Sun Gateway, with its vision of a radiant<br />

Cosmic Deity framed by a multitude of running or<br />

kneeling attendants brandishing shamanic staffs, is regarded as<br />

<strong>the</strong> core expression of Andean highland religion.<br />

The monumental sculptural frieze switches between two<br />

renditions of this winged attendant, which is replicated in<br />

horizontal rows flanking <strong>the</strong> cosmic icon. One version of<br />

<strong>the</strong> figure has a human face; <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r is transformed into a<br />

bird with <strong>the</strong> conspicuous beak of one of <strong>the</strong> large raptors or<br />

vultures that dominate <strong>the</strong> Andean skies, such as <strong>the</strong> condor or<br />

harpy eagle.<br />

Wari tunic design typically selects one of <strong>the</strong>se two icons,<br />

but also conceives o<strong>the</strong>r variants of <strong>the</strong> figure, including one<br />

endowed with feline characteristics. Here <strong>the</strong> staff-bearer<br />

retains human form but acquires a fanged mouth and a doubled<br />

open/split eye. The image is rendered in a style moving toward<br />

overall geometric abstraction, emphasizing <strong>the</strong> play of circular,<br />

square and rectangular shapes distributed throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

composition. Recent scholarship has been reluctant to pursue<br />

(and even refutes) connections between Chavín iconography<br />

and <strong>the</strong> traditions that developed subsequently in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

sierra. However, this link is awakened by <strong>the</strong> proposition that<br />

certain renderings of <strong>the</strong> Wari staff emblem ei<strong>the</strong>r directly<br />

represent <strong>the</strong> San Pedro cactus, or allude to it via a distinctive<br />

candelabra-like finial and headdress ornament.<br />

Recent scholarship has been reluctant to pursue (and even<br />

refutes) connections between Chavín iconography and <strong>the</strong><br />

traditions that developed subsequently in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn sierra.<br />

However, this link is awakened by <strong>the</strong> proposition that certain<br />

renderings of <strong>the</strong> Wari staff emblem ei<strong>the</strong>r directly represent<br />

<strong>the</strong> San Pedro cactus, or allude to it via a distinctive candelabralike<br />

finial and headdress ornament.<br />

At Chavín de Huántar, a ritualist bearing a naturalistic San<br />

Pedro cactus is portrayed in a procession converging on a<br />

paramount deity. If information <strong>from</strong> that scene is transposed<br />

to Wari iconography, and <strong>the</strong> connective tissue supplied<br />

by Tiwanaku imagery of <strong>the</strong> magic cactus is taken into<br />

consideration, it is tenable to interpret this staff motif as also<br />

signifying that sacred plant, which was a pan-Andean agent of<br />

psychedelic experience.<br />

The tri- or multipart branching motif, which evokes a cluster of<br />

flower-tipped cactus stalks, dominates this design. It decorates<br />

both <strong>the</strong> headdress and <strong>the</strong> staff (“expanded" following <strong>the</strong><br />

classic Wari stylistic conventions), and in a visual pun on <strong>the</strong><br />

shape of a fea<strong>the</strong>r, it is conflated with <strong>the</strong> wing. The element<br />

is also placed upside-down behind <strong>the</strong> rear arched foot, thus<br />

diagonally echoing <strong>the</strong> identical emblem embellishing <strong>the</strong> top<br />

of <strong>the</strong> staff and deftly balancing <strong>the</strong> composition.<br />

40

144<br />

Fragment <strong>from</strong> a Tunic<br />

Avian Attendant Bearing Vilca<br />

Wari culture<br />

AD 600-900<br />

Camelid wool; interlocking tapestry weave<br />

10" x 8½"<br />

A<br />

<strong>the</strong>me of shamanic duality underpins <strong>the</strong> depiction of <strong>the</strong><br />

staff-bearers surrounding <strong>the</strong> Cosmic Deity on <strong>the</strong> Sun<br />

Portal at Tiwanaku.<br />

The retinue comprises two distinct figures that are multiplied<br />

in three rows across <strong>the</strong> span of <strong>the</strong> frieze. Apart <strong>from</strong> subtle<br />

variations in <strong>the</strong> placement or combination of symbolic details,<br />

<strong>the</strong> regalia and profile running stances of each figure are<br />

identical—yet <strong>the</strong>ir heads (and feet) reveal an essential contrast.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> upper and lower registers of <strong>the</strong> design, winged staffbearers<br />

with human features maintain a forward gaze on <strong>the</strong><br />

paramount deity. In <strong>the</strong> center row, however, <strong>the</strong> personage<br />

takes on <strong>the</strong> craned head and powerful beak of a crested eagle<br />

or hawk.<br />

This dramatic alternation implies a shamanic or ecstatic<br />

transfiguration, and indeed a symbol for <strong>the</strong> spirit plant<br />

Anadenan<strong>the</strong>ra colubrina or vilca is carved on <strong>the</strong> face of <strong>the</strong> birdheaded<br />

attendant. The taking of hallucinogenic powders derived<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> crushed seeds of this mimosa-like tree was prevalent<br />

across <strong>the</strong> Tiwanaku sphere. Several of <strong>the</strong> monumental figural<br />

sculptures enshrined at <strong>the</strong> ceremonial center portray mythical<br />

ancestors or ritualists holding snuff tablets, and a large array<br />

of snuffing paraphernalia has been unear<strong>the</strong>d throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

region (especially in nor<strong>the</strong>rn Chile and Argentina.<br />

As this exceptionally beautiful woven image demonstrates,<br />

<strong>the</strong> raptor’s supernatural association with this particular<br />

psychoactive plant was carried into Wari imagery. Like birds<br />

depicted on many Tiwanaku painted vessels, <strong>the</strong> eagle-headed<br />

figure conspicuously grasps <strong>the</strong> vilca seedpod in its beak. But<br />

<strong>the</strong> reference is also encoded in a schematic element that is<br />

prominently integrated into <strong>the</strong> design. The striated stirrupshape<br />

topped with two circles, which sprouts <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> headdress,<br />

eye, shoulder and knees, has been interpreted as a stylization of<br />

<strong>the</strong> globular flowers and leaves of Anadenan<strong>the</strong>ra. 1<br />

It seems likely that <strong>the</strong> raptor was regarded as <strong>the</strong> “spirit" or<br />

mythical benefactor of this hallucinogen—aptly so, because<br />

<strong>the</strong> substance induces a strong sensation of flying. In <strong>the</strong><br />

Andean cosmovision, moreover, eagles, hawks and falcons<br />

escort shamans to <strong>the</strong> upper levels of <strong>the</strong> cosmos. As <strong>the</strong> true<br />

masters of <strong>the</strong> sky, endowed with extraordinary gifts of flight<br />

and eyesight, <strong>the</strong>y are fitting attendants for a solar and thunder<br />

divinity such as Tiwanaku’s Staff Deity.<br />

Yet Wari ideas differed <strong>from</strong> Tiwanaku, and are often more<br />

bellicose. Although this interpretation is largely faithful to <strong>the</strong><br />

stone image, <strong>the</strong> shamanic bird actually carries a severed head<br />

instead of <strong>the</strong> usual staff. (Although this pertinent detail is now<br />

missing <strong>from</strong> this fragment, it is known <strong>from</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sections of<br />

<strong>the</strong> same tunic. 2 The trophy-head motif, which connects <strong>the</strong><br />

icon with Wari ritual sacrifice and warfare, revives notions of<br />

this bird as an arch predator and fierce hunter.<br />

Vilca Symbols on Eye, Chest and Headdress<br />

1 Patricia Knobloch, “Wari Ritual Power at Conchopata: An Interpretation of<br />

Anadenan<strong>the</strong>ra Colubrina Iconography,” Latin American Antiquity 11, no. 4 (2000): 387-<br />

402.<br />

2 Ibid.<br />

43

145<br />

Fragment <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shoulder of a Tunic<br />

A Male and Female Pair of Condor Staff-Bearers<br />

Wari culture<br />

AD 600-900<br />

Camelid wool; interlocking tapestry weave<br />

19" x 5½"<br />

The entire body of Wari tunic iconography can be charted<br />

on a design spectrum, moving inexorably towards an<br />

endpoint of total abstraction. Indeed, this trajectory might<br />

be considered <strong>the</strong> apogee of an Andean textile aes<strong>the</strong>tic that<br />

began a millennium earlier with <strong>the</strong> modular constructivism of<br />

Chavín imagery.<br />

Since <strong>the</strong> tapestry tunics were produced over a period of at<br />

least 500 years, time was clearly a contributing factor in this<br />

progression. Several hypo<strong>the</strong>ses have also been advanced to<br />

explain this fascinating development. Alan Sawyer proposed,<br />

for example, that <strong>the</strong> patterning was increasingly compressed<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> outer edges of <strong>the</strong> tunic in order to create <strong>the</strong><br />

impression of a rounded volumetric or cylindrical shape that<br />

overrides <strong>the</strong> flat, square format of <strong>the</strong> garment.1 William<br />

Conklin has suggested, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, that <strong>the</strong> visual<br />

distortion that occurs as <strong>the</strong> image is repeated across <strong>the</strong> vertical<br />

bands reflects an Andean concept of one (or multiple) cosmic<br />

horizons toward which <strong>the</strong> flying mythical figure recedes (or<br />

<strong>from</strong> which it emerges), diminishing in scale and angle as it<br />

vanishes (or appears) in <strong>the</strong> distance. 2<br />

The result of <strong>the</strong> rectilinear compression and fracturing of<br />

<strong>the</strong> figure is evident in this interpretation of <strong>the</strong> staff-bearer<br />

attendant. Although partially outlined with a crisp white<br />

thread, <strong>the</strong> delineation barely compensates for <strong>the</strong> extreme<br />

compartmentalization of <strong>the</strong> avian form into myriad elliptical,<br />

square, oblong, circular, chevron, and irregularly shaped color<br />

blocks. The head of <strong>the</strong> bird is especially elusive, to <strong>the</strong> point<br />

of merging with <strong>the</strong> indigo background (top). That gives<br />

prominence to both <strong>the</strong> distinctive hooked beak of <strong>the</strong> bird<br />

of prey and <strong>the</strong> bisected eye, which is wrapped in a stylized<br />

creature that magnifies or shrinks in size depending on <strong>the</strong><br />

width allocated to <strong>the</strong> figure's head.<br />

Despite its cryptic quality, this Wari variant never<strong>the</strong>less<br />

incorporates <strong>the</strong> same curious motif that adorns <strong>the</strong> birdheaded<br />

attendant represented on <strong>the</strong> Sun Portal. The element,<br />

which consists of a small face with an exaggerated, upturned<br />

mouth, is thought to depict <strong>the</strong> now-extinct Lake Titicaca<br />

Oresteia’s fish. 3 Here this schematic face is set at <strong>the</strong> tip of <strong>the</strong><br />

staff, behind <strong>the</strong> foot and below <strong>the</strong> wing. Perhaps inspired by<br />

a fish eagle, <strong>the</strong> motif surely links this supernatural personage<br />

with that vast lake, which was regarded as a place of mythic and<br />

primordial origin.<br />

The iconography of this fragment is identical to that of a<br />

tunic excavated by Max Uhle at Pachacamac, <strong>the</strong> powerful<br />

ceremonial and oracle center on <strong>the</strong> central coast. 4 Without<br />

knowing whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>se related textiles were actually woven<br />

<strong>the</strong>re or brought <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> highlands, it is impossible to say<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> mythic significance of this fish motif was still<br />

pertinent among coastal peoples—or if <strong>the</strong> loss of context<br />

in fact stripped it and o<strong>the</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong>ir specific meanings, thus<br />

promoting <strong>the</strong> general stylization and reduction of form.<br />

1 Alan Sawyer, "Tiahuanaco Tapestry Design," Textile Museum Journal 1, no. 2 (1963):<br />

27-38.<br />

2 William Conklin, "The <strong>Mythic</strong> Geometry of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ancient</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Sierra," in The<br />

Junius B. Bird Conference 1984, ed. Anne Pollard Rowe (1986): 123-137.<br />

3 John Wayne Janusek, <strong>Ancient</strong> Tiwanaku (2008): fig. 5.5.<br />

4 Max Uhle, Pachacamac (1903): plate 4, fig. 2.<br />

44

146<br />

Fragment <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shoulder of a Tunic<br />

A Male and Female Pair of Condor Staff-Bearers<br />

Wari culture<br />

AD 600-900<br />

Camelid wool; interlocking tapestry weave<br />

19" x 5½"<br />

The tendency toward ever-increasing abstraction in Wari<br />

textile art was a collective phenomenon, surely driven<br />

as much by individual artistry as by <strong>the</strong> imposition of an<br />

official aes<strong>the</strong>tic. Certainly, local styles and <strong>the</strong>mes might<br />

have influenced <strong>the</strong> development of Wari design. That aspect<br />

might be better understood if it were possible to determine<br />

<strong>the</strong> geographic location of various weaving workshops, <strong>the</strong>reby<br />

associating stylistic nuances and innovations with distinct<br />

regions (north/south or coast/highlands).<br />

In this case, <strong>the</strong> compressed rectilinearity and complexity<br />

of <strong>the</strong> image may not solely reflect <strong>the</strong> band’s proximity to<br />

<strong>the</strong> outer sides of <strong>the</strong> tunic, but also suggests an intensified<br />

approach to figural deconstruction and distortion. The play of<br />

elongated elements on both <strong>the</strong> vertical and horizontal axes is<br />

especially pronounced.<br />

Without recourse to <strong>the</strong> overall composition and to <strong>the</strong><br />

matching parallel bands of design, <strong>the</strong> alternating diagrammatic<br />

figures are best decoded through comparison with related<br />

iconography. Two avian staff-bearers alternate in <strong>the</strong> sequence,<br />

switching back and forth in direction, and expanding or<br />

contracting according to typical Wari canons. The pattern<br />

mosaic obscures a subtle differentiation of attribute and<br />

geometry in each image. 1<br />

The most significant distinction is that one of <strong>the</strong> pair<br />

(bottom) displays a large knob on its beak, which apparently<br />

alludes to <strong>the</strong> comb or caruncle of <strong>the</strong> male condor, while<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r (center) does not, just like <strong>the</strong> female of <strong>the</strong> species.<br />

The distinctive shape of this beak indicates that <strong>the</strong> feature is<br />