The Women's IP World Annual 2019/2020

We are delighted to present you with the launch edition of The Women’s IP World Annual 2019/2020, celebrating women at all levels working in IP Law and Innovation. From the very beginning, the response and feedback we had was amazing, and we would like to thank all of the incredible women involved. Our aim was to celebrate a group of diverse women, from all over the globe, showcasing their achievements and also their personalities to inspire and inform. We have taken an unbiased approach and kept the articles & profiles as authentic as possible, to keep the author's own personal style. This has resulted in a cocktail of inspirational women coming together to share thoughts, ideas, and experience positively. We hope you enjoy this issue as much as we have enjoyed putting it together. Ms. Elvin Hassan Editor & Head of International liaisons

We are delighted to present you with the launch edition of The Women’s IP World Annual 2019/2020, celebrating women at all levels working in IP Law and Innovation. From the very beginning, the response and feedback we had was amazing, and we would like to thank all of the incredible women involved. Our aim was to celebrate a group of diverse women, from all over the globe, showcasing their achievements and also their personalities to inspire and inform. We have taken an unbiased approach and kept the articles & profiles as authentic as possible, to keep the author's own personal style. This has resulted in a cocktail of inspirational women coming together to share thoughts, ideas, and experience positively. We hope you enjoy this issue as much as we have enjoyed putting it together.

Ms. Elvin Hassan

Editor & Head of International liaisons

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Being Intellectual Property Rights,<br />

Trademarks are negative rights, as<br />

against positive rights created by other<br />

property rights. <strong>The</strong>refore, where a<br />

party to a Trademark dispute is found<br />

not to have a right, that party cannot<br />

prevent others from freely using the<br />

Trademark.<br />

EXCLUSIVE RIGHTS OF<br />

TRADEMARKS<br />

Trademarks are generally defined as marks<br />

which distinguish the goods and services of<br />

one enterprise from the other. <strong>The</strong>y are assets<br />

of value to businesses and can further be<br />

exploited through licences. Businesses invest<br />

significant resources in their Trademarks and<br />

take steps to protect such Trademarks from<br />

being infringed by competitors. Trademark<br />

protection, like any other Intellectual<br />

Property Right, is territorial in nature; thus,<br />

protection in one country does not guarantee<br />

protection in another. In this regard, it is<br />

not surprising that businesses aware of the<br />

value of their intellectual property develop<br />

strategies to manage their Trademarks.<br />

Strategic management of Trademarks include<br />

strategies for protection, exploitation, and<br />

enforcement of their rights.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rights acquired by a Trademark owner<br />

confer the right to exclude others from using<br />

the mark on the same or similar goods and<br />

services without the consent of the rights<br />

owner. Despite the exclusive rights conferred<br />

on a Trademarks owner, it does not obtain<br />

a monopoly. As aptly stated in a plethora of<br />

decided cases, “[I]intellectual Property Rights<br />

are not monopolies.”<br />

Trademark rights may be obtained through<br />

registration or the common law right of<br />

use. Where there is a conflict in ownership<br />

of a Trademark between parties, municipal<br />

laws provide the answer. Some jurisdictions<br />

apply the first to file system as against the<br />

GHANA<br />

TRADEMARKS<br />

EXCLUSIVITY:<br />

THE HAMPTA CASE 1<br />

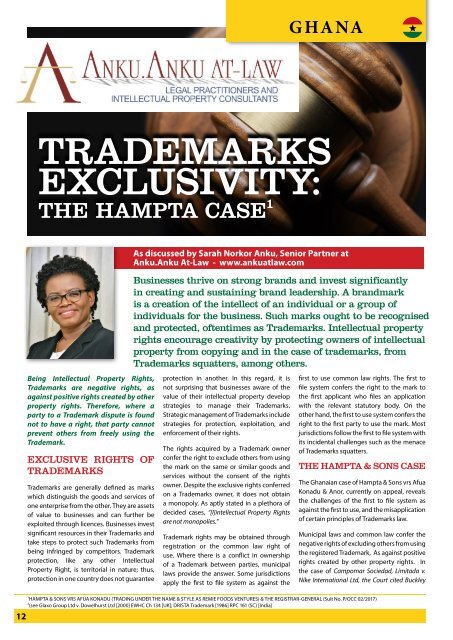

As discussed by Sarah Norkor Anku, Senior Partner at<br />

Anku.Anku At-Law - www.ankuatlaw.com<br />

Businesses thrive on strong brands and invest significantly<br />

in creating and sustaining brand leadership. A brandmark<br />

is a creation of the intellect of an individual or a group of<br />

individuals for the business. Such marks ought to be recognised<br />

and protected, oftentimes as Trademarks. Intellectual property<br />

rights encourage creativity by protecting owners of intellectual<br />

property from copying and in the case of trademarks, from<br />

Trademarks squatters, among others.<br />

first to use common law rights. <strong>The</strong> first to<br />

file system confers the right to the mark to<br />

the first applicant who files an application<br />

with the relevant statutory body. On the<br />

other hand, the first to use system confers the<br />

right to the first party to use the mark. Most<br />

jurisdictions follow the first to file system with<br />

its incidental challenges such as the menace<br />

of Trademarks squatters.<br />

THE HAMPTA & SONS CASE<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ghanaian case of Hampta & Sons vrs Afua<br />

Konadu & Anor, currently on appeal, reveals<br />

the challenges of the first to file system as<br />

against the first to use, and the misapplication<br />

of certain principles of Trademarks law.<br />

Municipal laws and common law confer the<br />

negative rights of excluding others from using<br />

the registered Trademark, As against positive<br />

rights created by other property rights. In<br />

the case of Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v.<br />

Nike International Ltd, the Court cited Buckley<br />

LJ in Lyle and Kinahan Ltd, where Buckley LJ,<br />

“…pointed out that the only right conferred by<br />

registration was a right to prevent others from<br />

using the trademark as a mark for their goods.”<br />

Trademarks Act, 2004 (Act 664), as amended,<br />

governs Trademarks in Ghana. <strong>The</strong> Act confers<br />

on a Trademark owner the right to prevent<br />

others from using the Trademark without<br />

authorisation of the registered owner. This is<br />

particularised in Section 9 of the Act. Section<br />

9 (2) is to the effect that it is only a registered<br />

owner of a Trademark who has a right to<br />

institute court action against any person<br />

who infringes the registered Trademark. In<br />

Aremu v. Lilaram Thawards , it was held that<br />

“A person is only entitled to have absolute and<br />

exclusive right to the use of a trademark if a<br />

certification of registration in respect of the<br />

trademark has been issued to him. In this case,<br />

since no certificate had been issued in respect of<br />

the trademark, the plaintiff’s action against the<br />

defendants was not maintainable.”<br />

BRIEF FACTS OF THE CASE<br />

Both the Plaintiff, HAMPTA, and the 1st<br />

Defendant, Konadu, trade in spices at<br />

Kumasi, the second-largest city in Ghana.<br />

While the HAMPTA trades in spices under<br />

the unregistered Trademark MINAZEN, the<br />

Konadu trades in spices under the Trademark<br />

REMIE. In July 2018, HAMPTA, decided to<br />

register its mark MINAZEN at the Trademarks<br />

Office, 2nd Defendant, only to realize<br />

that Konadu had applied to the Office to<br />

register the mark in her name. Based on the<br />

application for registration, Konadu solicited<br />

the help of the Police to harass the HAMPTA<br />

officials. All efforts to restrain her from these<br />

acts of unfair competition failed. HAMPTA,<br />

therefore, resorted to the High Court of<br />

Ghana for redress. While the substantive<br />

matter was pending, Konadu filed for an<br />

interlocutory injunction against HAMPTA.<br />

Subsequently, the trial judge injuncted both<br />

parties from using the mark MINAZEN even<br />

though Konadu had stated in her processes<br />

that she does not trade in spices with the<br />

mark MINAZEN. <strong>The</strong> judge stated in his<br />

interlocutory ruling dated 26th October 2017,<br />

on page 11, as follows:<br />

“I do not intend to go into the merits of the<br />

conflicting claims of the parties, the vexed<br />

question of who owns the exclusive right to<br />

the MINAZEN trademark will be determined<br />

after a full trial. What is apparent is that<br />

none of the parties has an exclusive right<br />

to the use of the MINAZEN trademark, as<br />

the applications of both parties are yet to<br />

be determined by the Registrar General’s<br />

Department. Indeed, the rights of parties<br />

could only be determined after parties have<br />

led evidence in support of their case, and all<br />

the pieces of evidence have been evaluated.<br />

It will, therefore, be prejudicial to conclude<br />

that a party, particularly the applicant, has<br />

a right to which ought to be protected…<br />

In conclusion, the judge held on page 12<br />

of his ruling that, “Both the applicant and<br />

respondent are, however, restrained<br />

forthwith from using the MINAZEN<br />

trademark to package their products and<br />

subsequently marketing, distributing and<br />

selling the same…”<br />

ANALYSIS AND<br />

CHALLENGES<br />

Enforcement of Trademarks hinges on the<br />

municipal laws of each State. In Mattel Inc v.<br />

3894207 Canada Inc 2006 SCC 22 [Canada],<br />

the Supreme Court of Canada cautioned, in<br />

the case of the enforcement of a registered<br />

Trademark, that “[f]airness, of course, requires<br />

consideration of the interest of the public and<br />

other merchants and the benefits of open<br />

competition as well as the interest of the<br />

trademark owner in protecting its investment in<br />

the mark. Care must be taken not to create a zone<br />

of exclusivity and protection that overshoots<br />

the purpose of trademark law. <strong>The</strong> purpose of a<br />

trademark is to create and symbolize linkages”.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Protection Against Unfair Competition<br />

Act of Ghana, 2000 (Act 598) ensures that<br />

intellectual property rights are not abused to<br />

the extent of creating monopolies.<br />

In addressing matters of trade, one cannot<br />

lose sight of issues relating to competition as<br />

the propensity of some players of the market<br />

to apply unfair practices to compete unfairly.<br />

It is for this reason, among others that the law<br />

on Protection Against Unfair Competition<br />

seeks to regulate fair practices in trade,<br />

including Intellectual Property Rights.<br />

In the case of HAMPTA & Sons, did the judge<br />

err in law by injuncting both parties from<br />

using the mark “MINAZEN”? Did he overshoot<br />

the purpose of Trademarks law? Was he fair to<br />

the merchant who had acquired a reputation<br />

in the mark through use even though not<br />

registered? Was his decision in the interest of<br />

promoting trade?<br />

As stated by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> prophecies of what the courts will do<br />

in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are<br />

what I mean by the law”… the law lies in the<br />

bosom of the judge.<br />

Konadu was the first to file the mark<br />

“MINAZEN,” even though she does not use<br />

the mark, while HAMPTA is the first to use the<br />

mark and the later (in time) to apply to the<br />

Trademarks Office for registration.<br />

Konadu had emphatically stated that she<br />

does not trade in the mark “MINAZEN.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, it surmises that an injunction on<br />

both parties was an injunction against HAMTA<br />

only, which was busily trading in products<br />

bearing the mark while overlooking the<br />

adverse effect on the value of the brand. One<br />

would have expected that the judge would<br />

have considered section 9(2) of Act 664,<br />

which is to the effect that only a registered<br />

owner of a Trademark can initiate an action<br />

in infringement and refused the application<br />

of Konadu. Yet, he based his decision on a<br />

mere application for registration, despite<br />

citing the Aremu case supra. Again one would<br />

have expected the Court to have frowned<br />

on such acts of unfair competition, where a<br />

competitor squats on another’s Trademarks<br />

just because the user of the mark had not<br />

registered it.<br />

In this case, Konadu had no right in law to<br />

initiate an injunction application against<br />

HAMPTA to prevent it from using a mark that<br />

it had traded in for many years, particularly,<br />

where the judge had found that both parties<br />

had applied for the registration of the mark<br />

‘MINAZEN,’ but none had been issued a<br />

certificate of registration. Surprisingly, despite<br />

his findings, the judge concluded without<br />

any legal basis, that both parties should be<br />

injuncted from using the mark even though<br />

none of the parties had the right to prevent<br />

the other from using the mark, as provided in<br />

section 9(1) of the Trademarks Act, 2003 (Act<br />

664), as amended, and to institute a court<br />

action against the other for using the mark in<br />

the first place, as provided in section 9(2)(a)<br />

of the Act and as decided in the Aremu case<br />

supra.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

<strong>The</strong> rights conferred on a Trademarks owner<br />

is settled; however, the interpretation of the<br />

term “Exclusive Rights,” has been misapplied<br />

in some cases. <strong>The</strong>re are a plethora of cases<br />

that expatiate the meaning of the term as<br />

negative rights, that is, a right to prevent<br />

others from using a registered Trademark<br />

as against positive rights of use. To avoid<br />

occasional misapplication of some of the basic<br />

principles of Intellectual Property Rights, it is<br />

highly recommended that businesses take<br />

steps to develop <strong>IP</strong>R management strategies<br />

that include seeking appropriate legal<br />

protection in markets of interest.<br />

1 HAMPTA & SONS VRS AFUA KONADU (TRADING UNDER THE NAME & STYLE AS REMIE FOODS VENTURES) & THE REGISTRAR-GENERAL (Suit No. P/OCC 02/2017)<br />

1 See Kirki AG v. Ritvik Holdings Inc 2005 SCC 65 [Canada]; DRISTAN Trademark supra; Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v. Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12 [Australia]<br />

2 (see Glaxo Group Ltd v. Dowelhurst Ltd [2000] EWHC Ch 134 [UK]; DRISTA Trademark [1986] RPC 161 (SC) [India]<br />

2<br />

(1964) GLR 253-256<br />

12 13